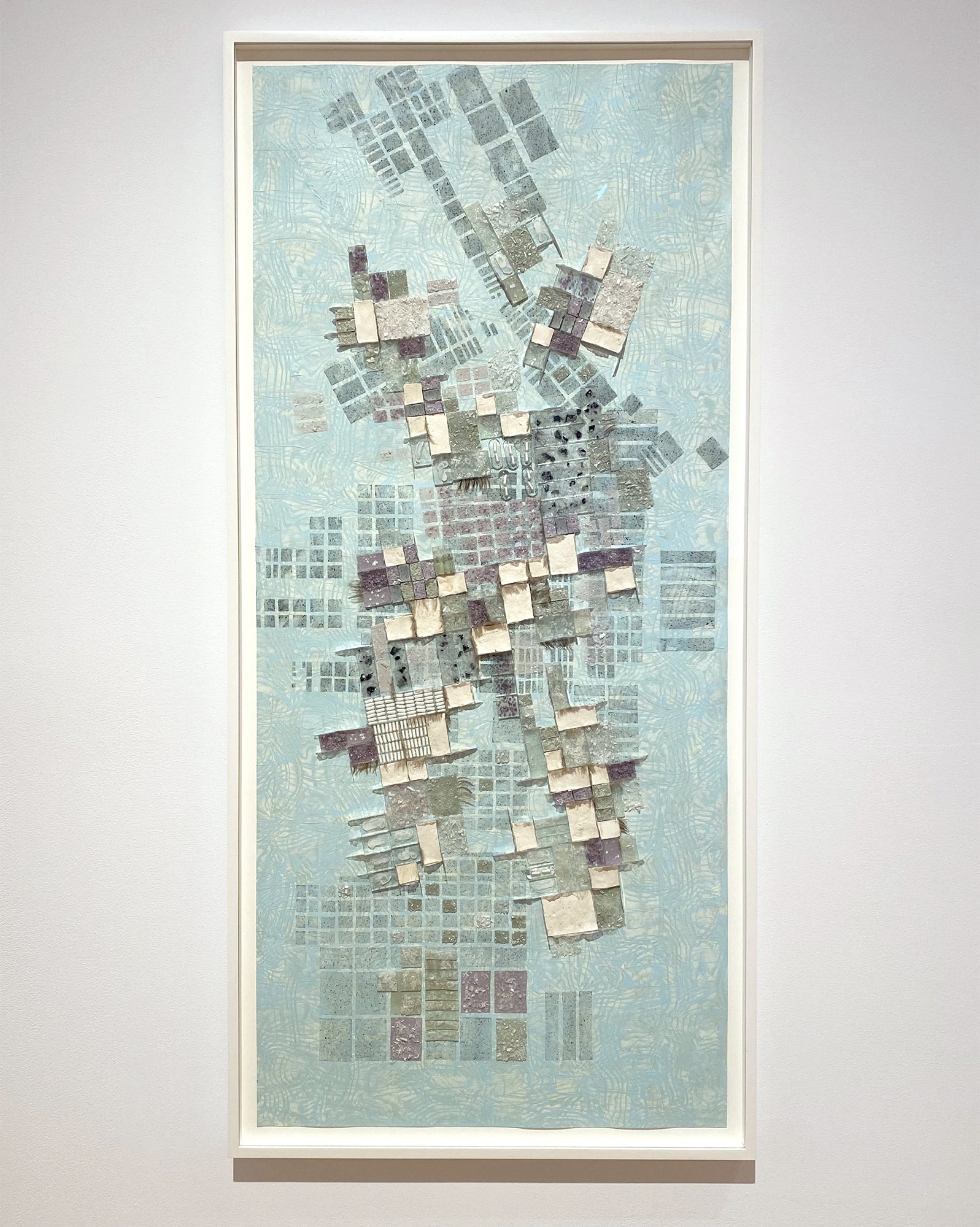

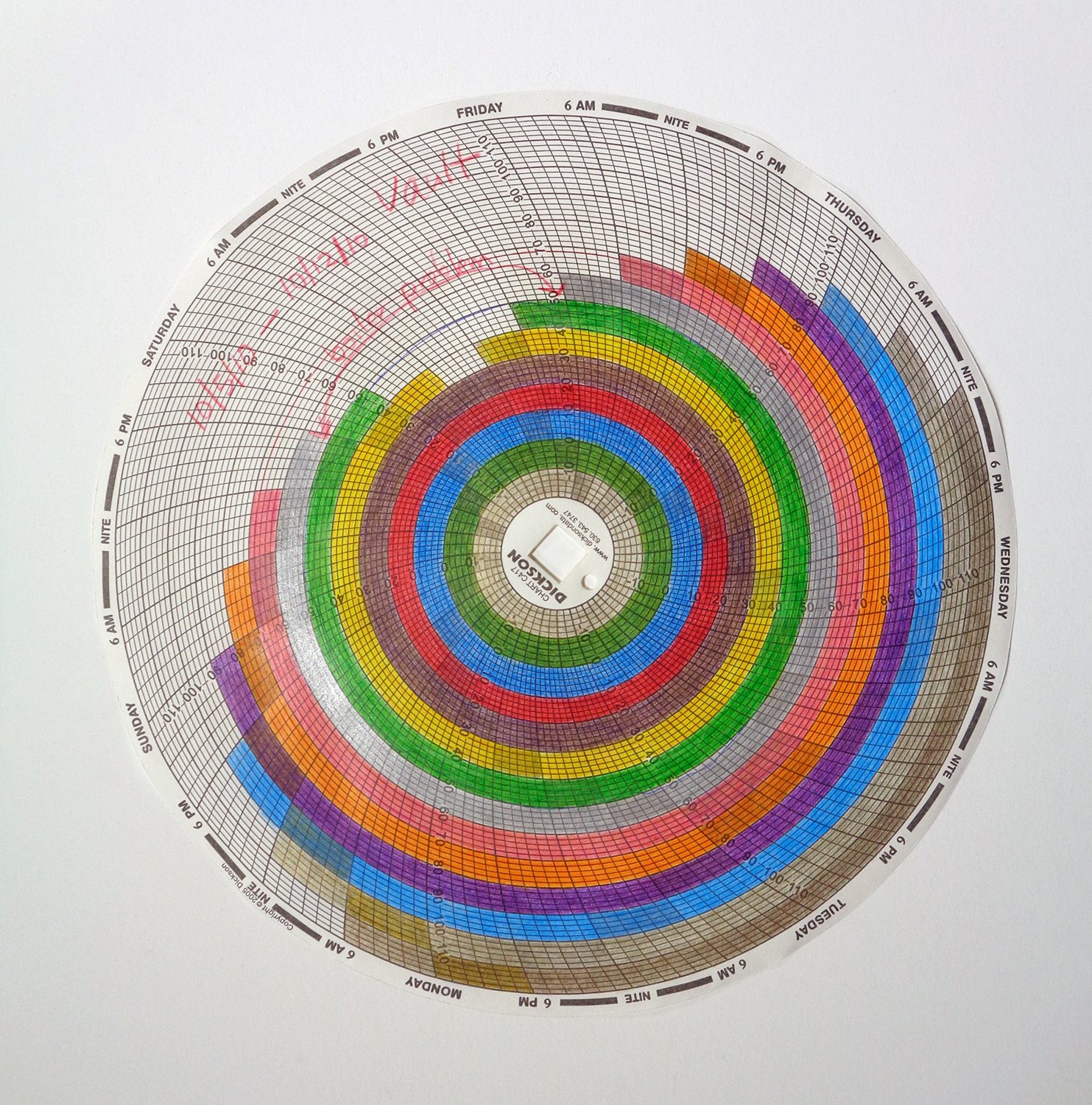

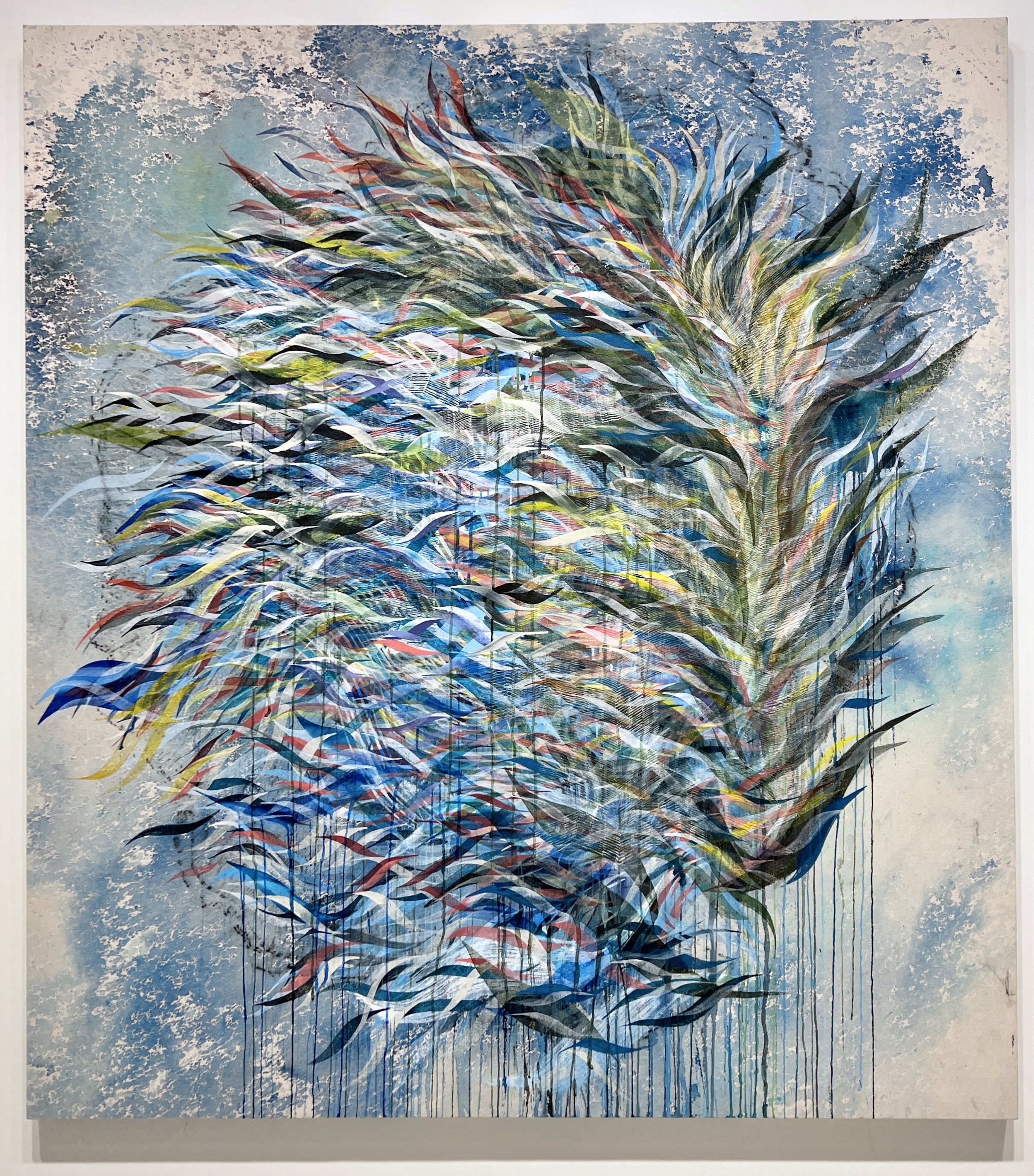

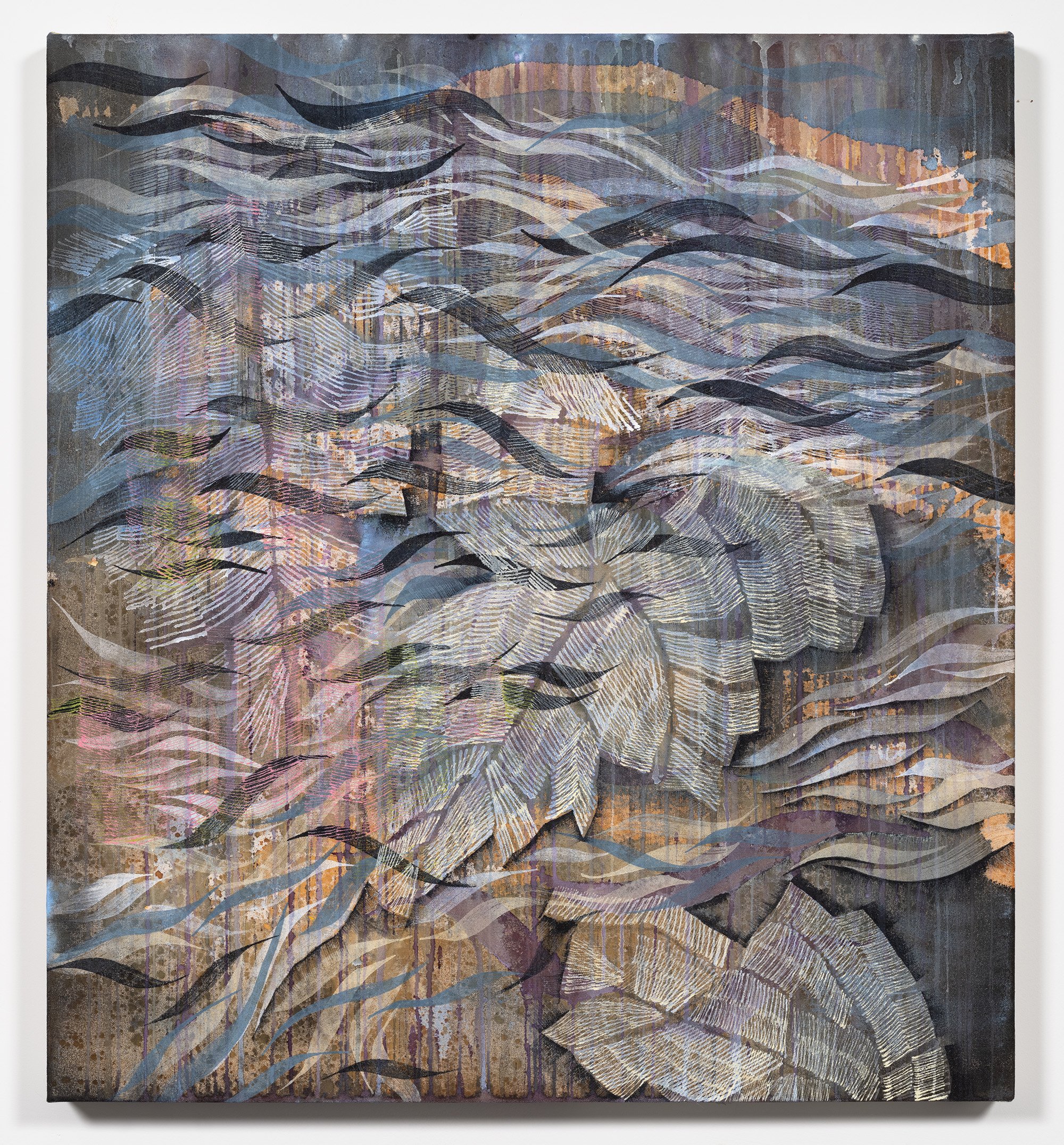

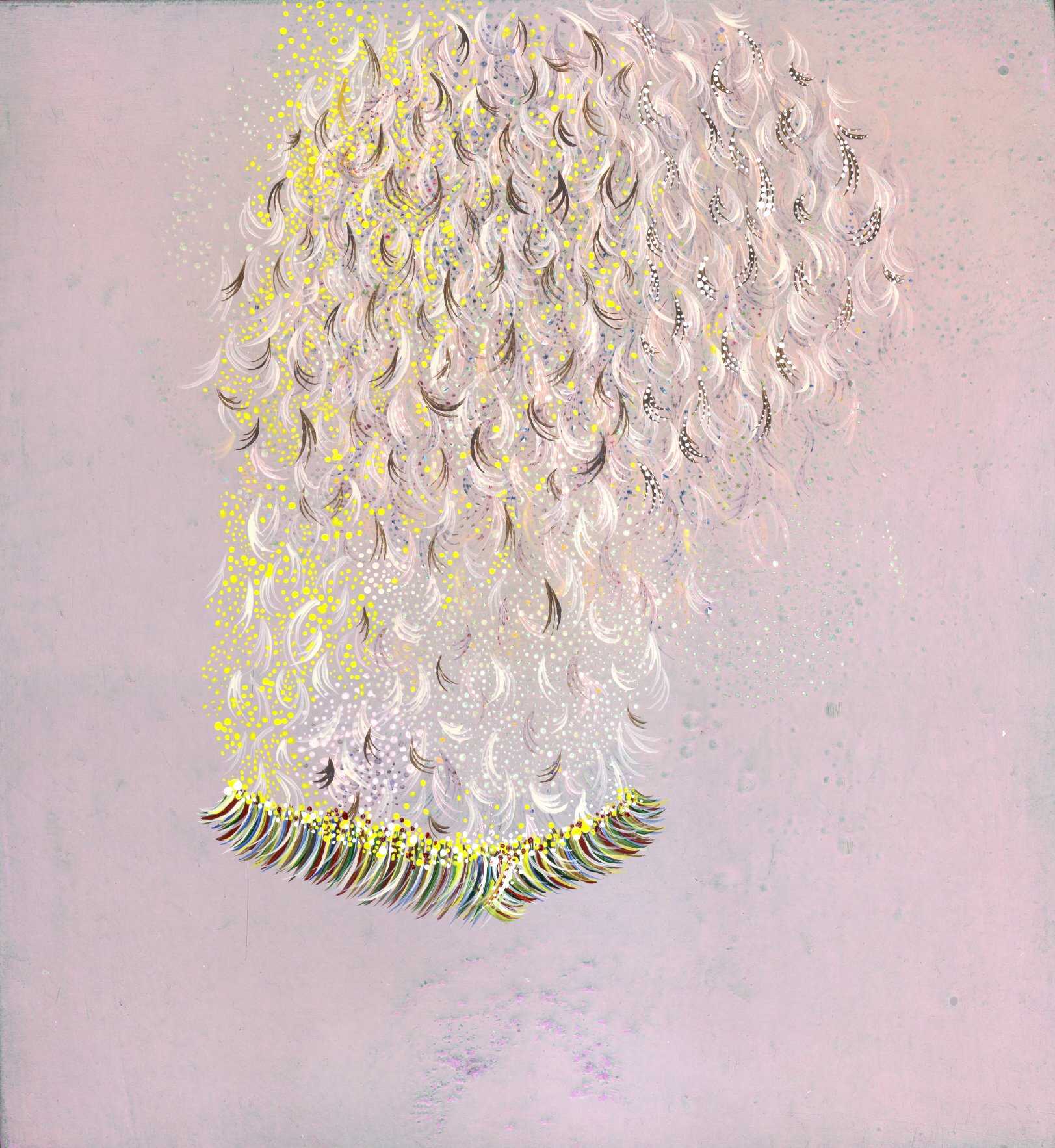

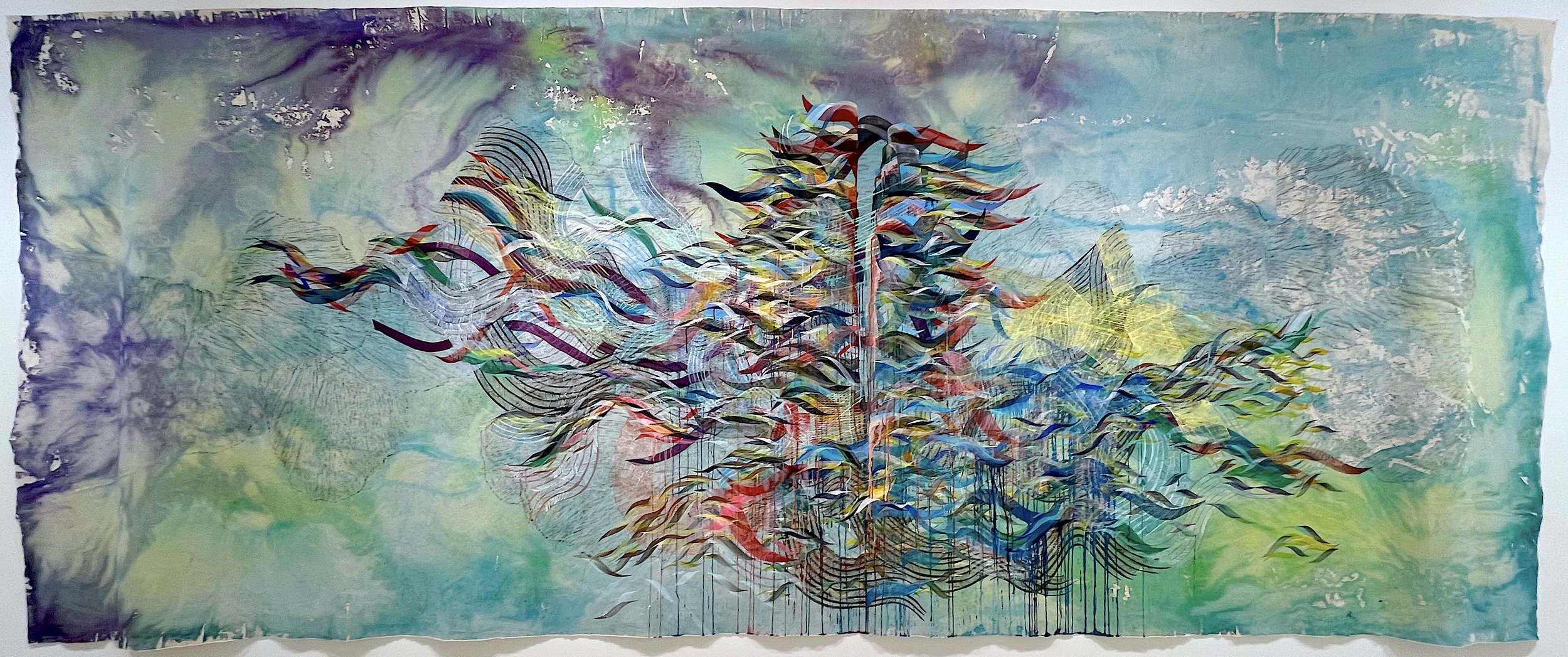

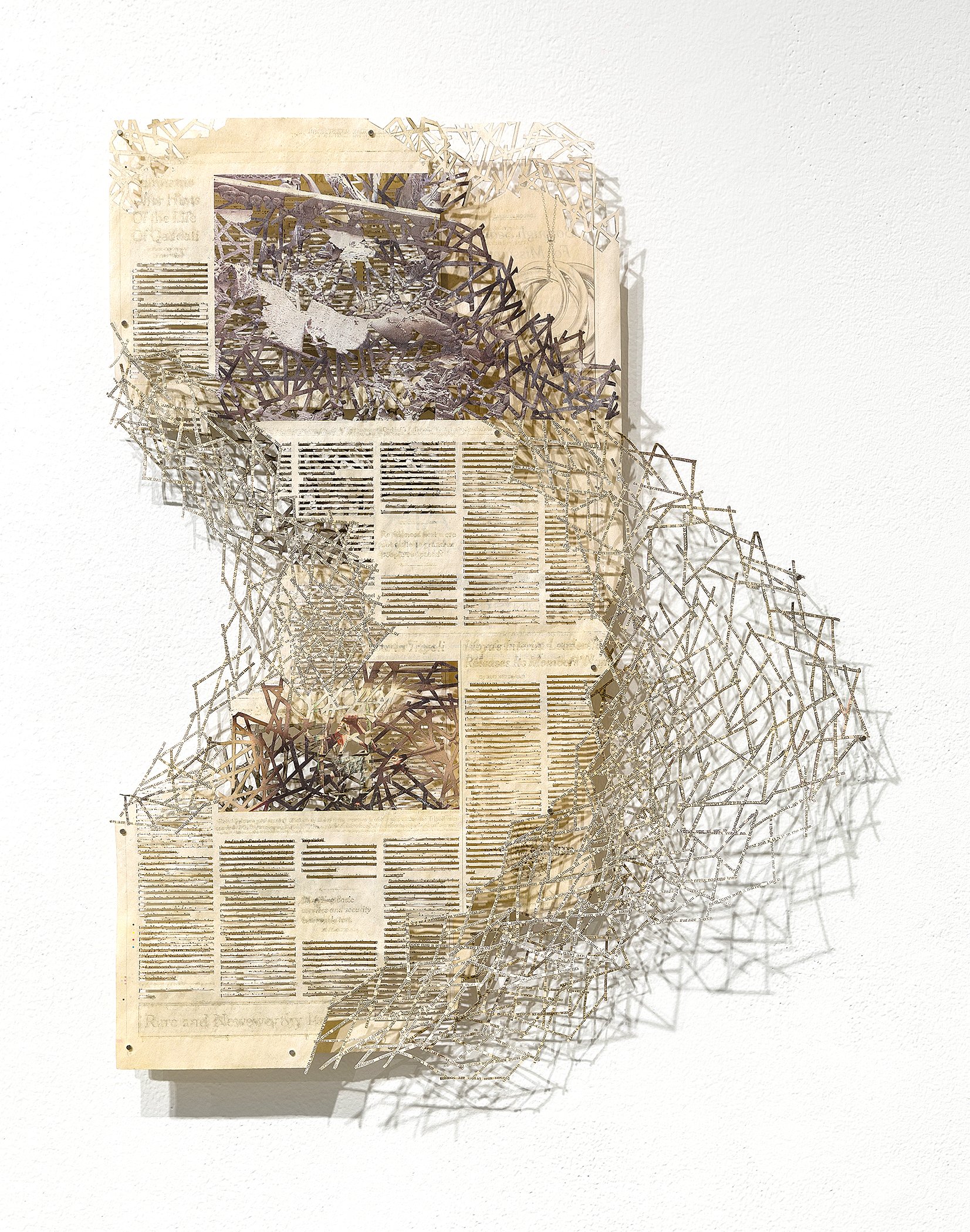

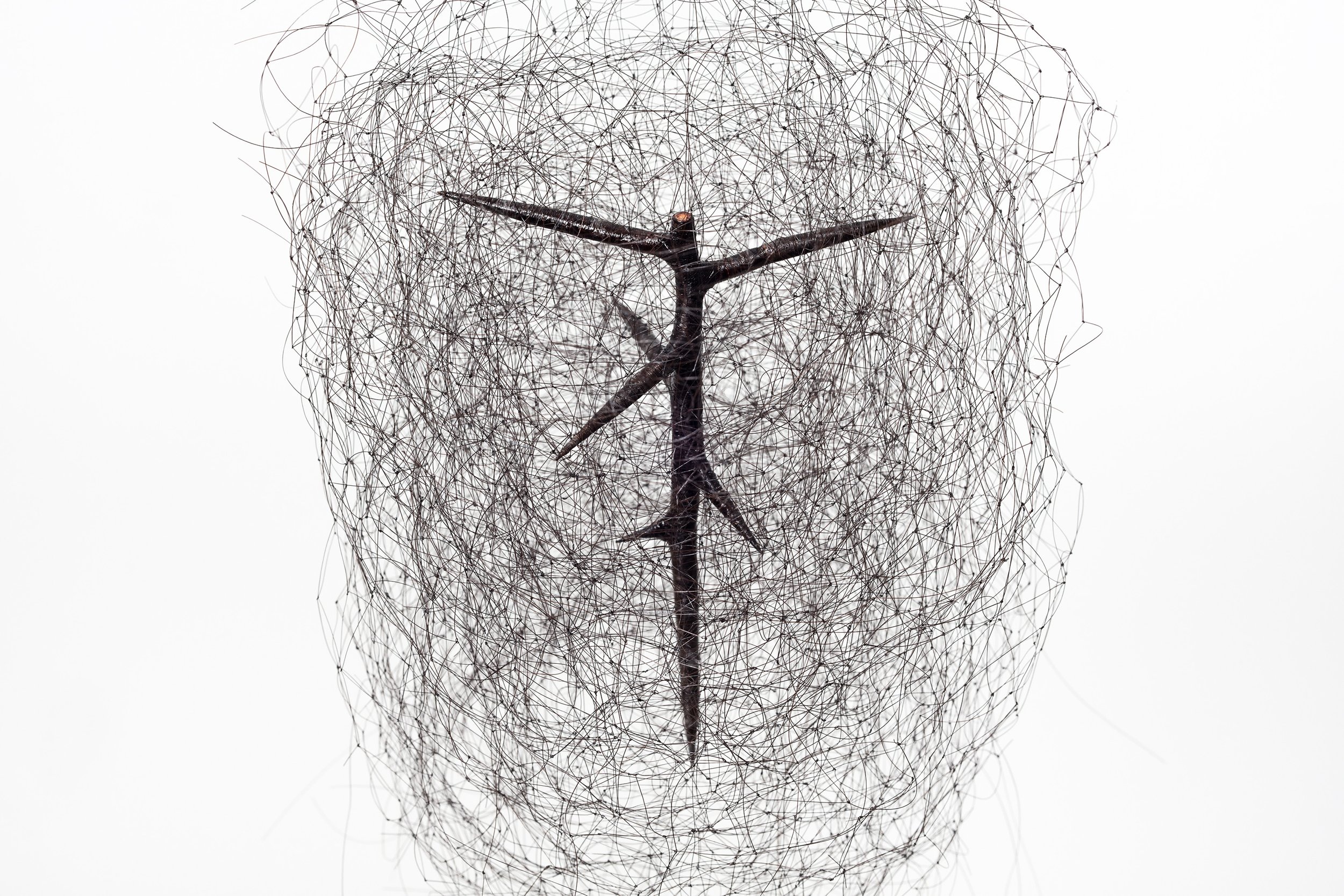

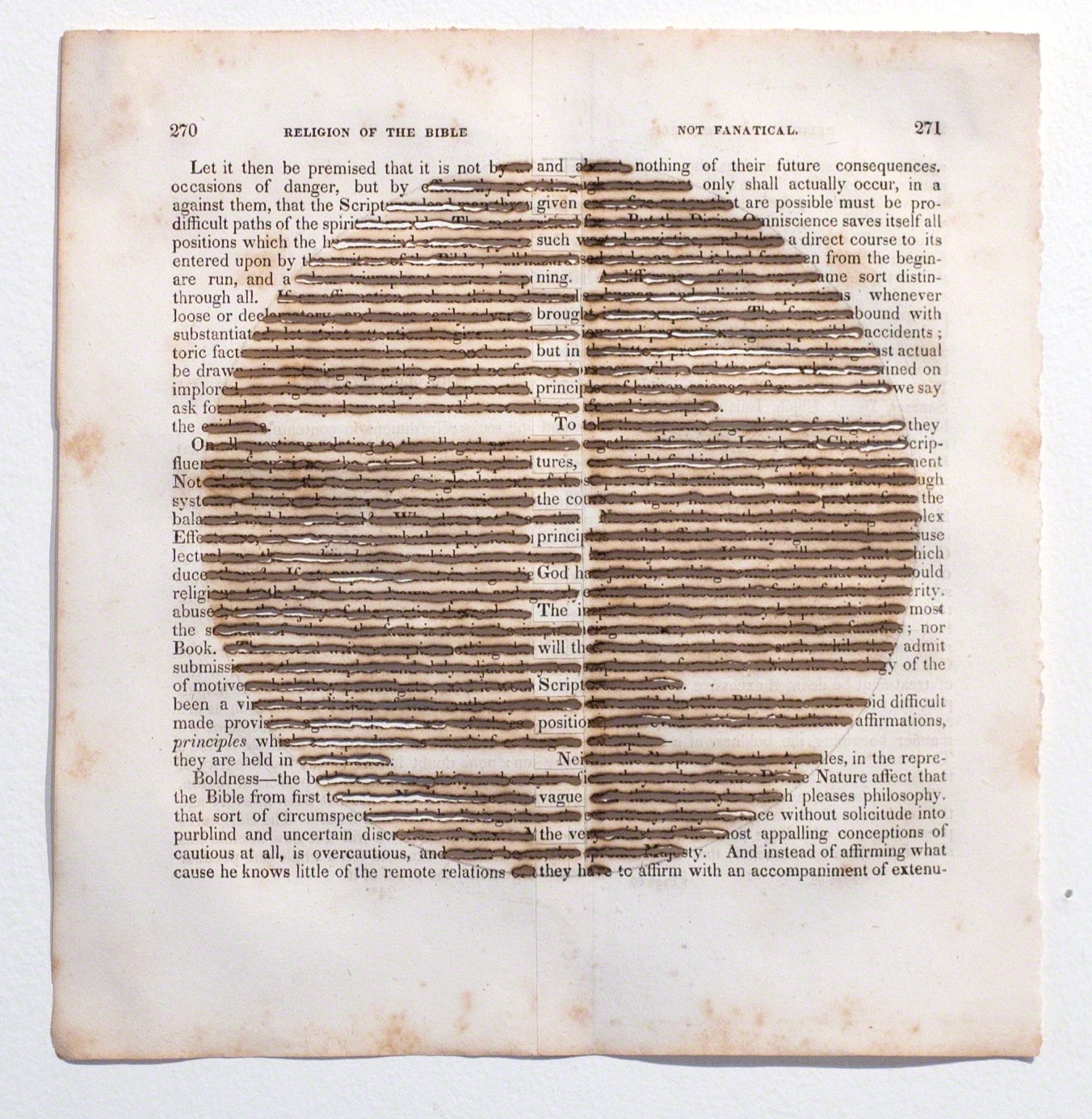

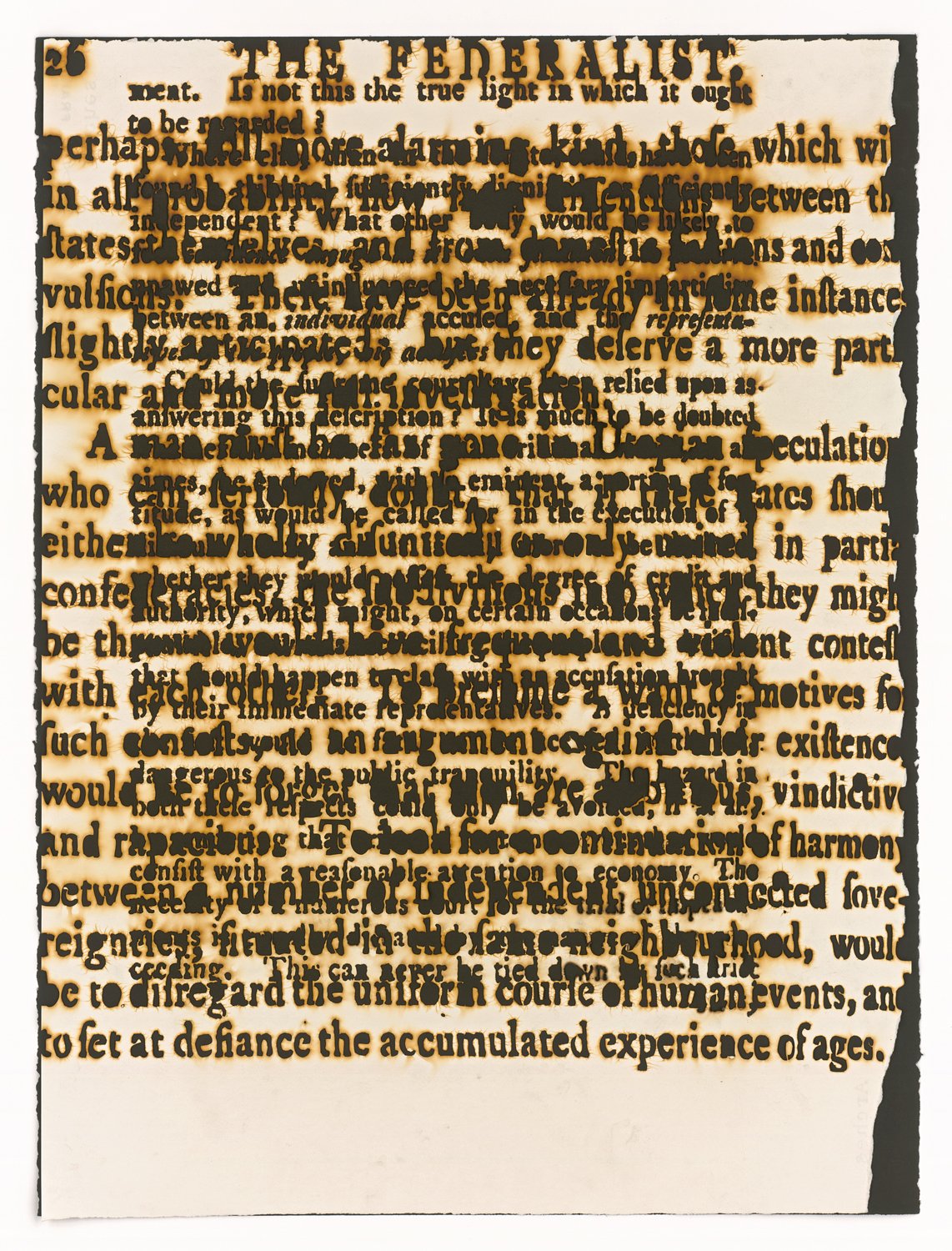

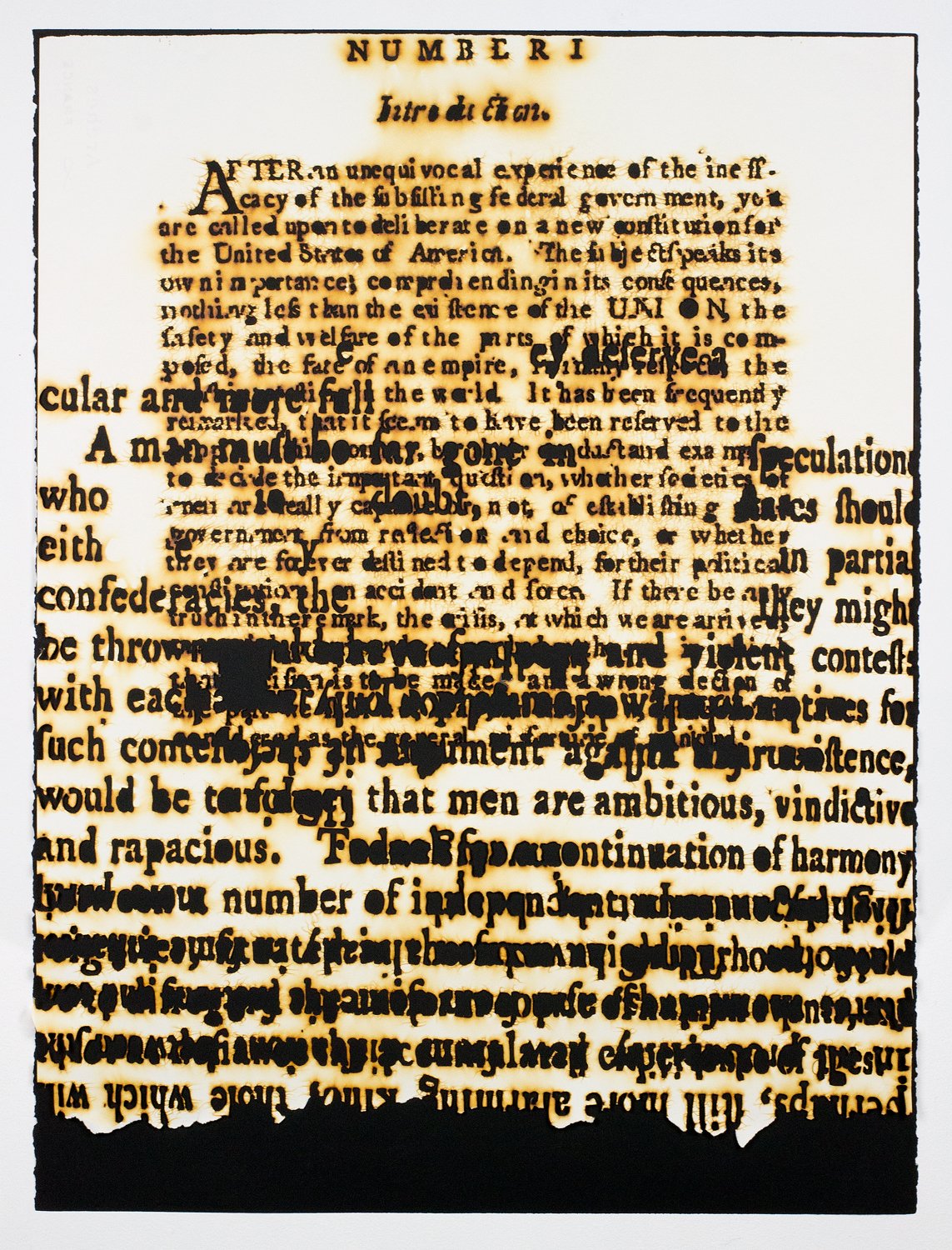

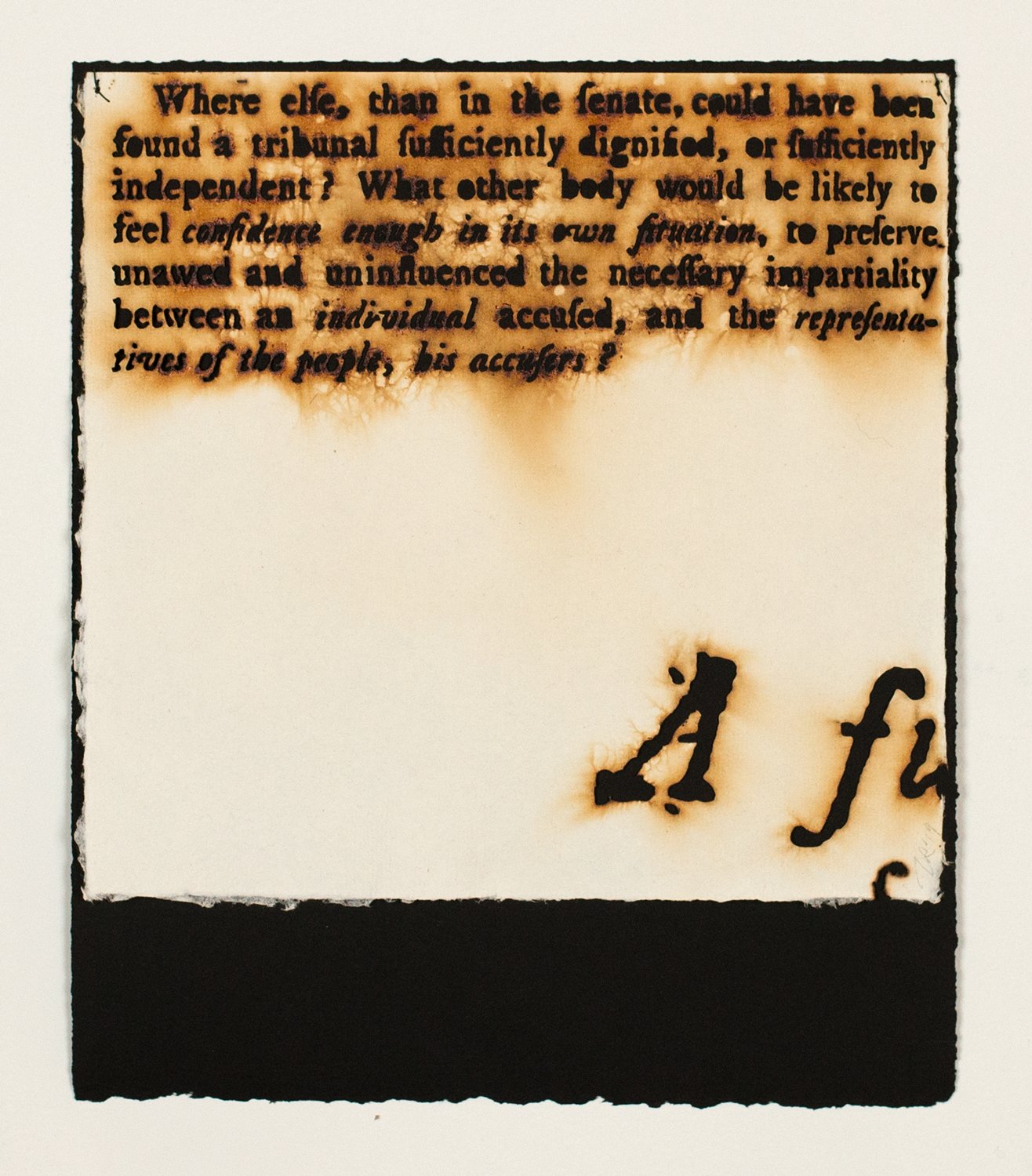

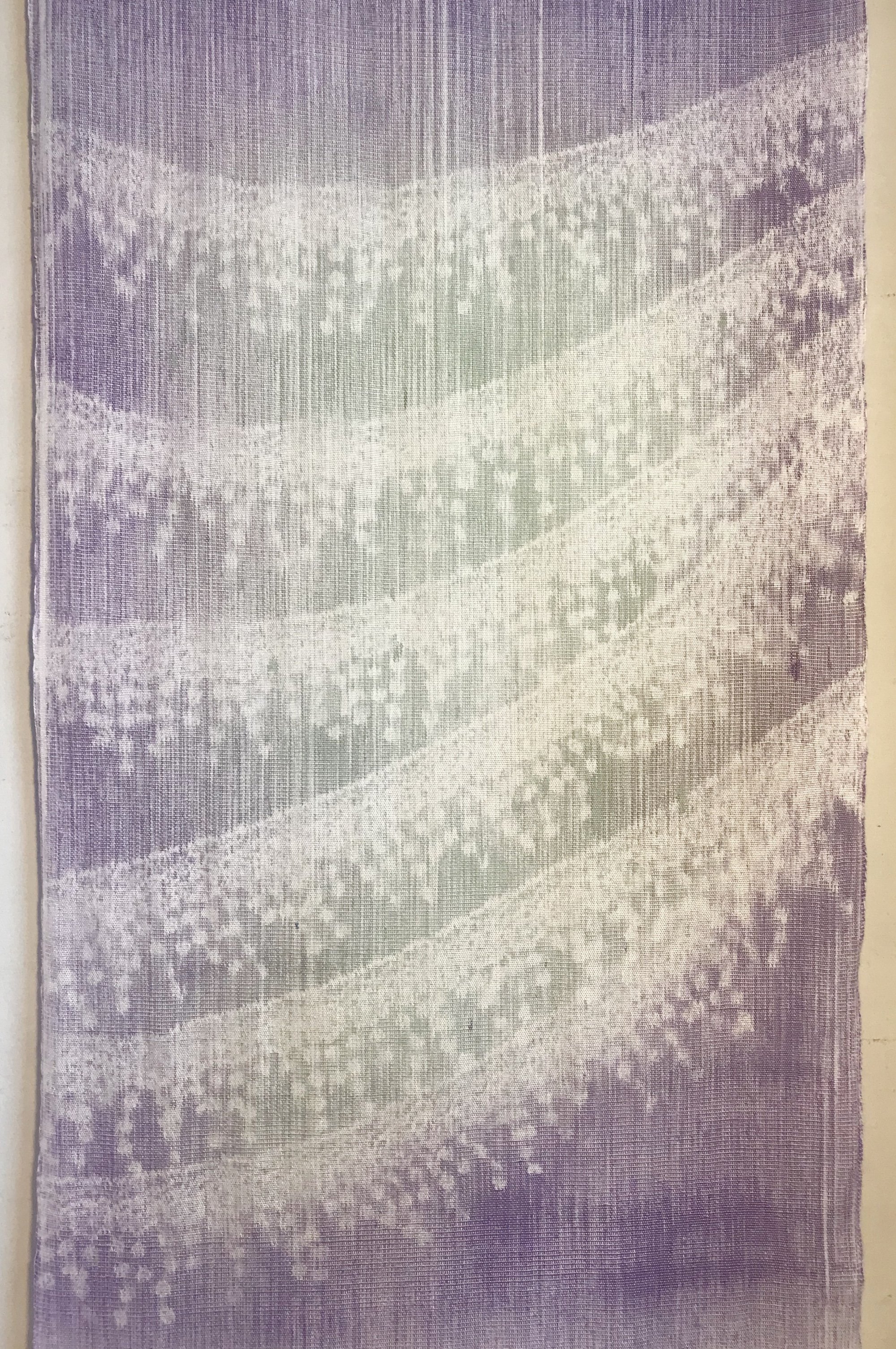

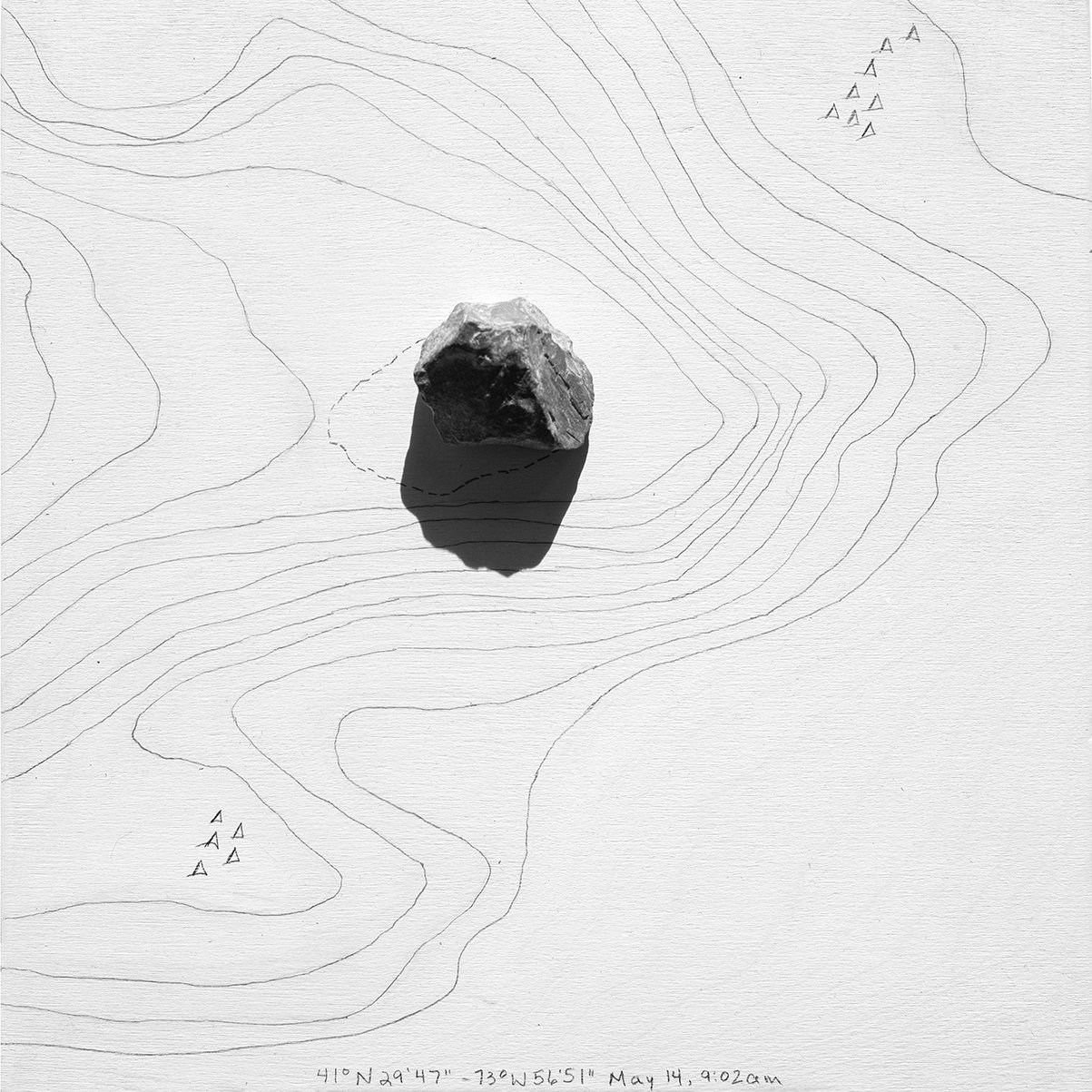

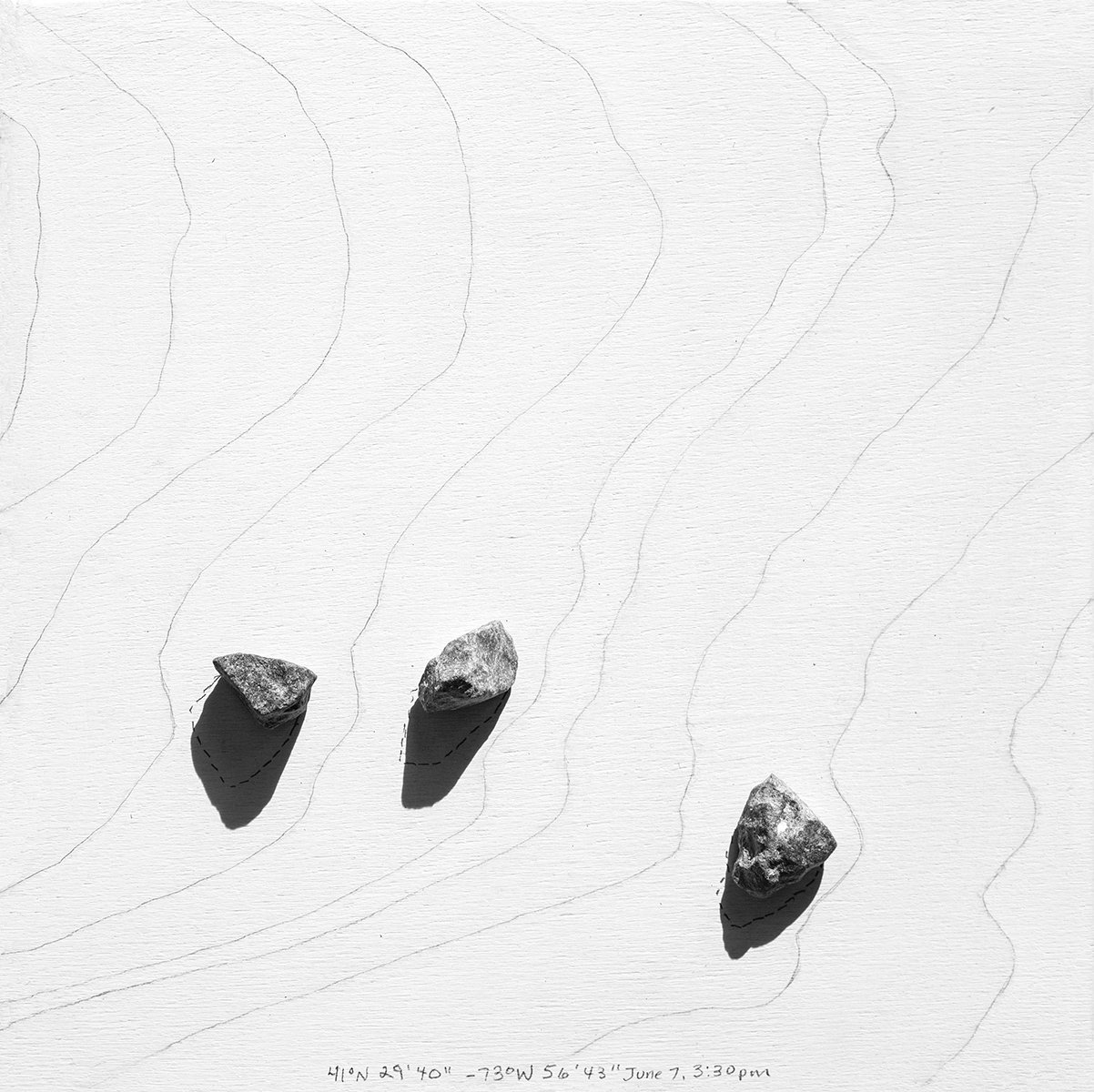

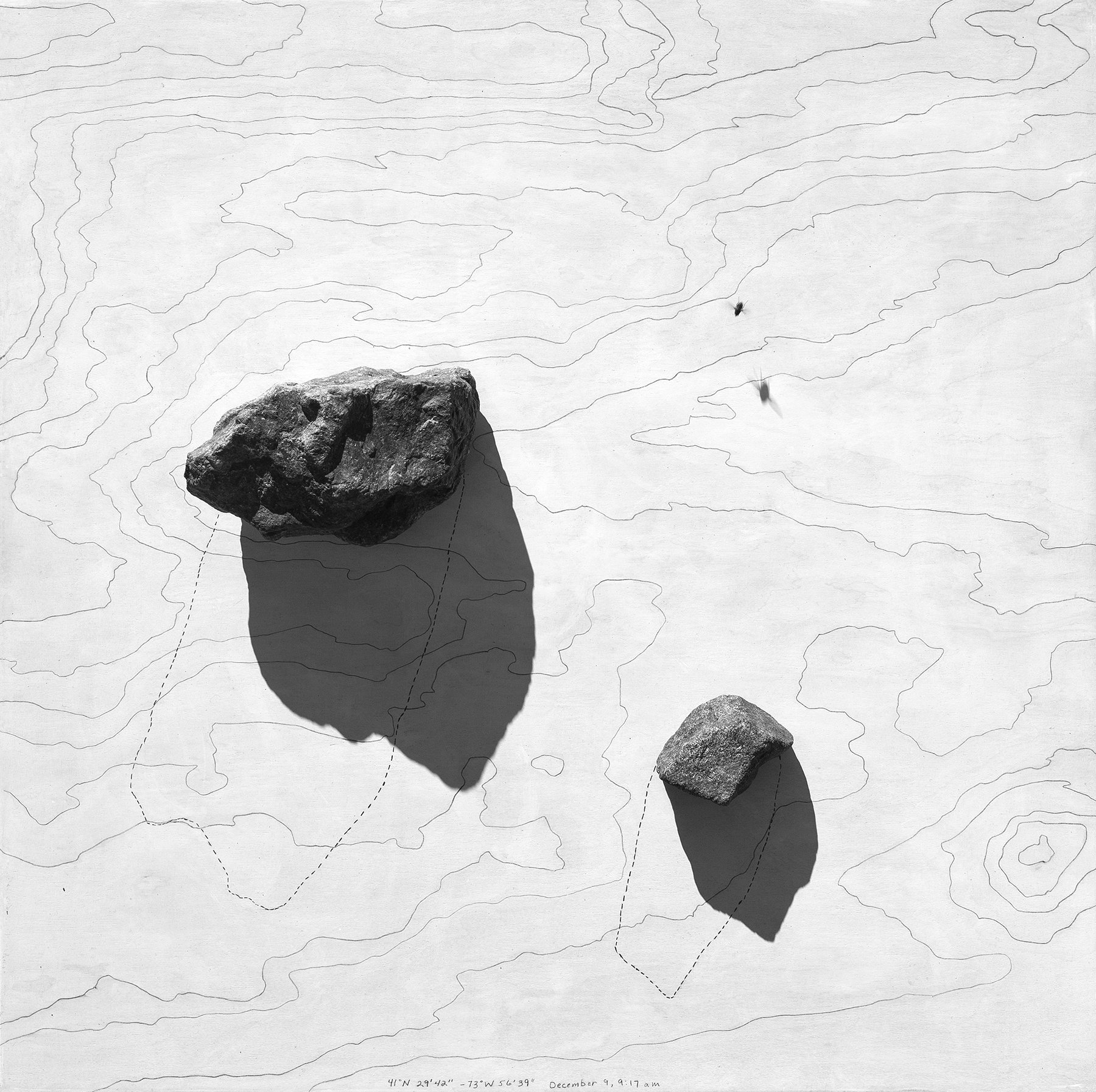

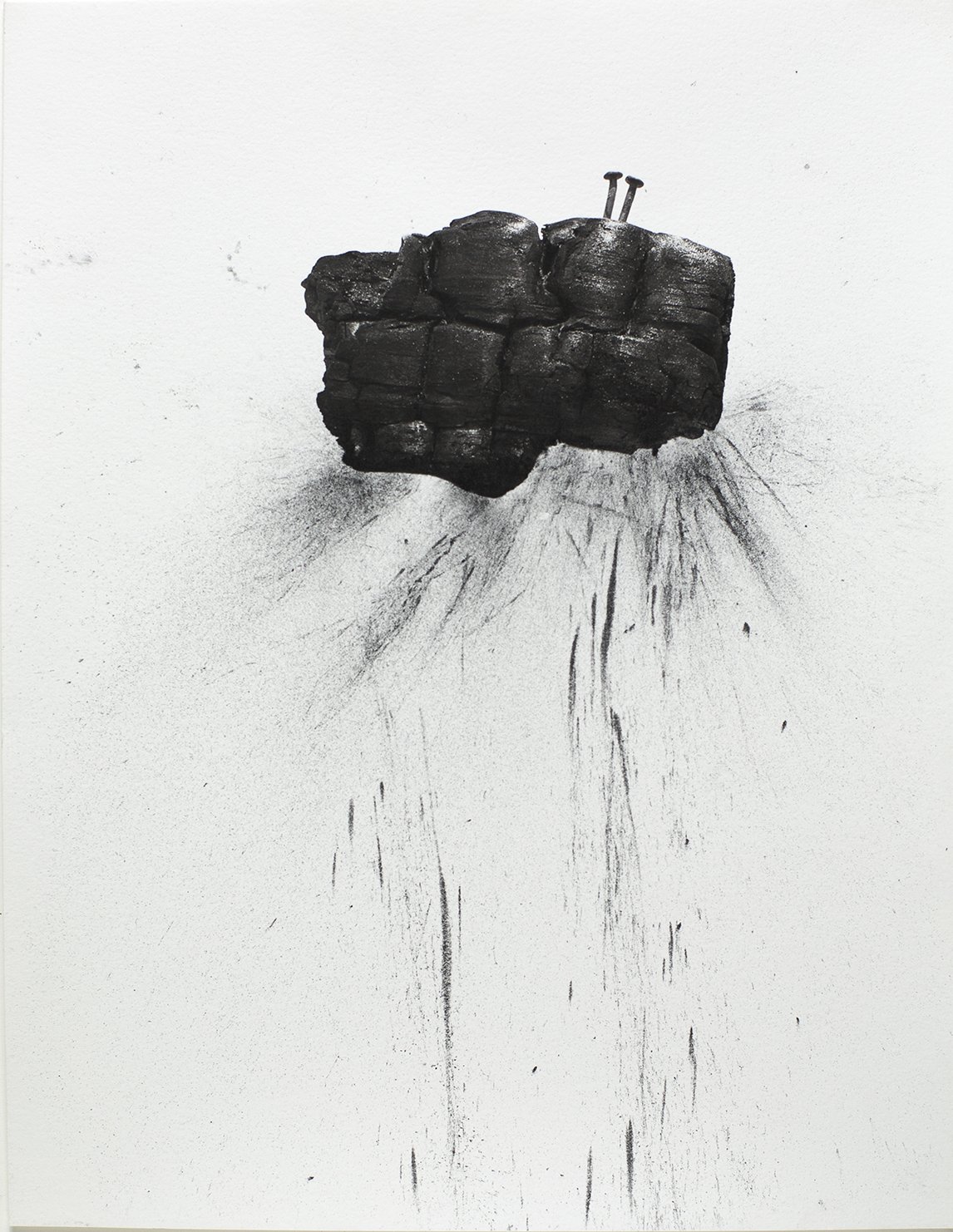

The equinox seems an appropriate time to share the work of Susan Walsh, as her focus is on the change of seasons, time-based processes, and the effects of the elements. Walsh is a multimedia artist whose materials include wind, rain, waves, and shadows. Her subject is time, and her object is to record it by setting up experiments that are at once scientific and poetic. She meticulously researches weather conditions and seasonal patterns, zeroing in on the optimal conditions for spontaneous mark making. This is a collaboration between the artist and the elements, and Walsh’s research involves finding the precise speed that the wind must blow to disperse the charcoal across, but not off, the paper. In another series, she determines the narrow season in which a piece of thread will cast a perfect, ink-like shadow across the paper (spoiler alert: it’s January through March), or the perfect admixture and amount of gouache so that when the rain pelts the paper, the pigments will separate and spatter just so. Walsh’s studio is a laboratory of trial and error, a labor of love and curiosity in which she painstakingly documents the patterns and quirks of her collaborator. By the time she places her paper in the elements, she has achieved a high level of predictability, with a generous tolerance for accidents. It’s the latter that excites Walsh, those unexpected natural events that leave irregular marks and remind her that no amount of record keeping can ensure an anticipated outcome. Walsh makes notations on the paper that include the date, time, and location of the commencement of the drawing. It also records notations such as the wind’s speed and direction, and these exhaustive details become the human mark, a fingerprint of the artist, so to speak, which is a ledger of where she was at a precise moment in time. In theory, if all her drawings were placed in chronological order, we would have a timeline of the artist’s movement across the landscape of her life. Walsh’s sundials similarly attest to the presence of the artist as she records the shapes and shadows cast by stone, nail, and thread. Everything is a sundial, according to Walsh, but it requires a scientist, poet, or artist to initiate the essential inquiry. Walsh is all of these, as she harnesses the power of the elements and uses them to create her elegant time- and nature-based works.

MH: To quote your artist statement, “The consistent theme of my work has been marking time through observable changes in natural phenomena.” When did you become interested in the passing of time, and why does it hold such interest for you?

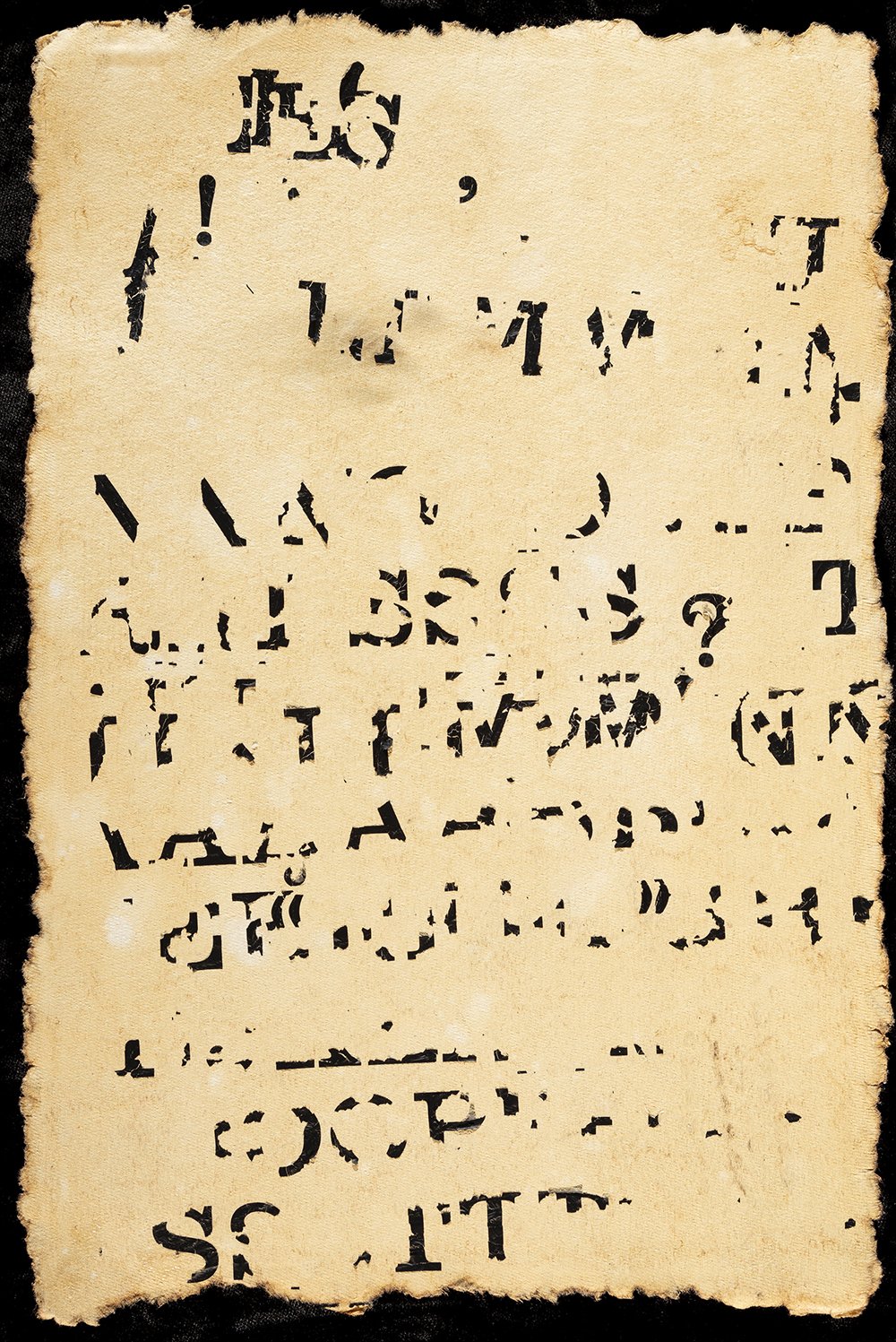

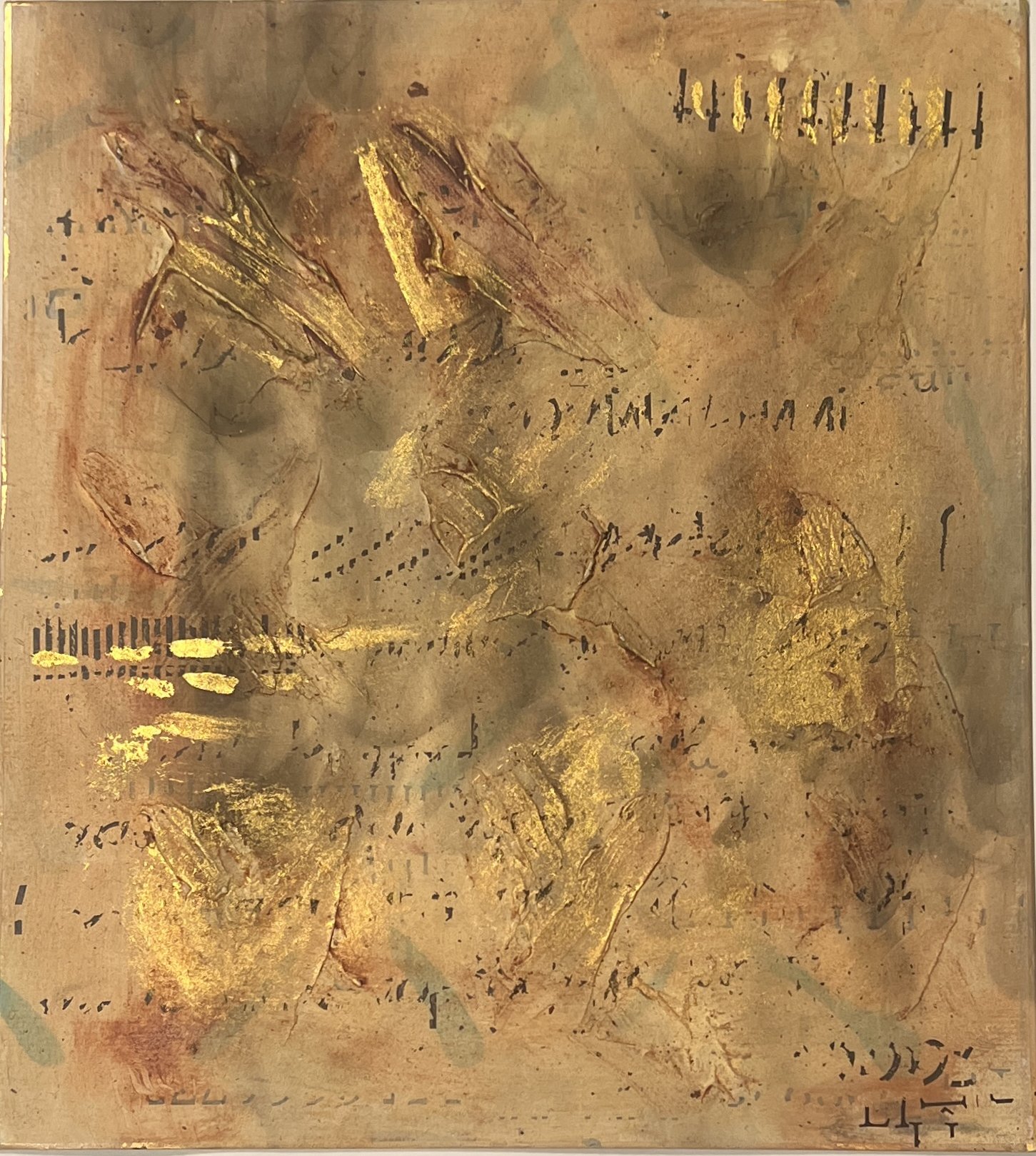

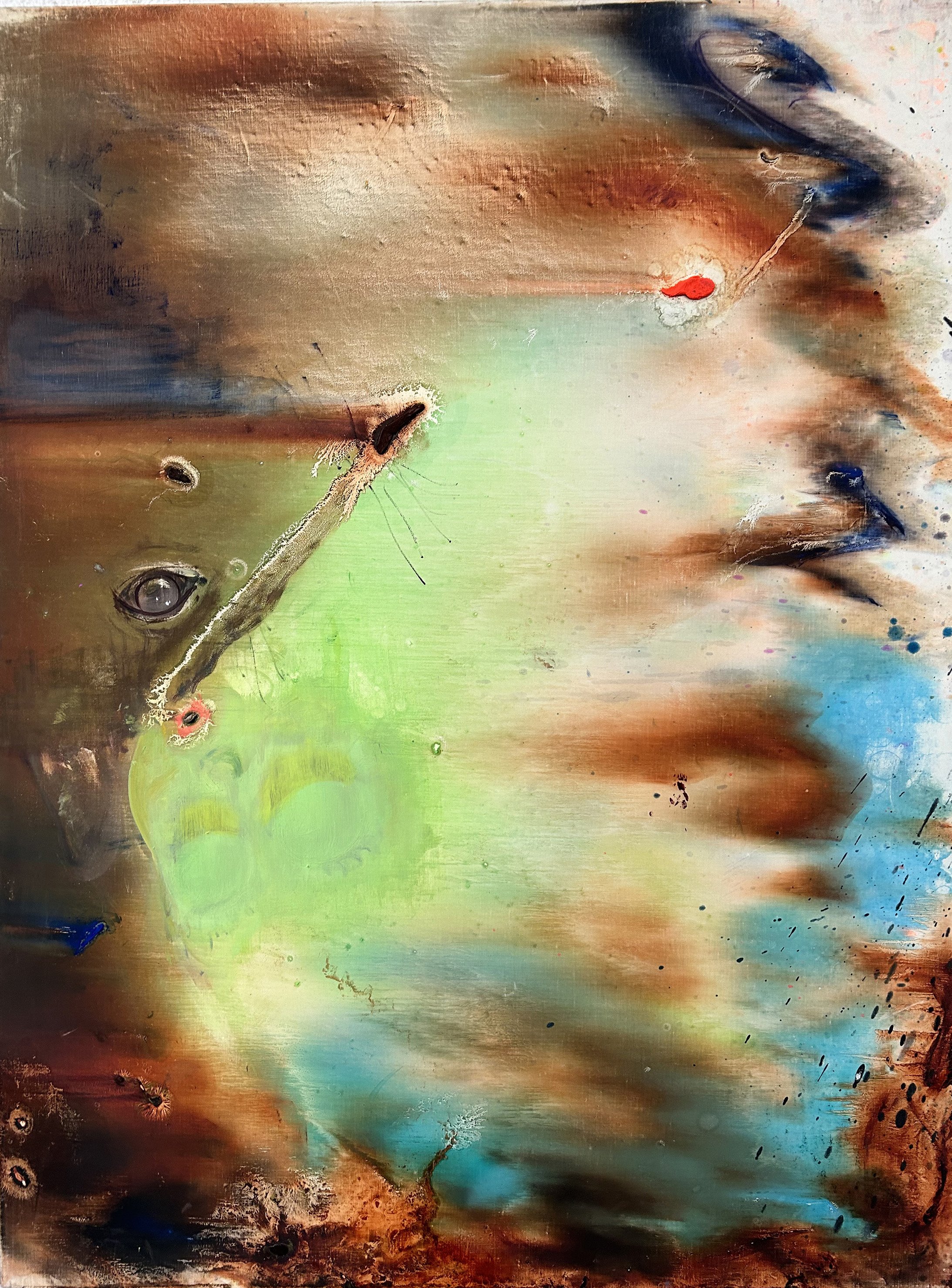

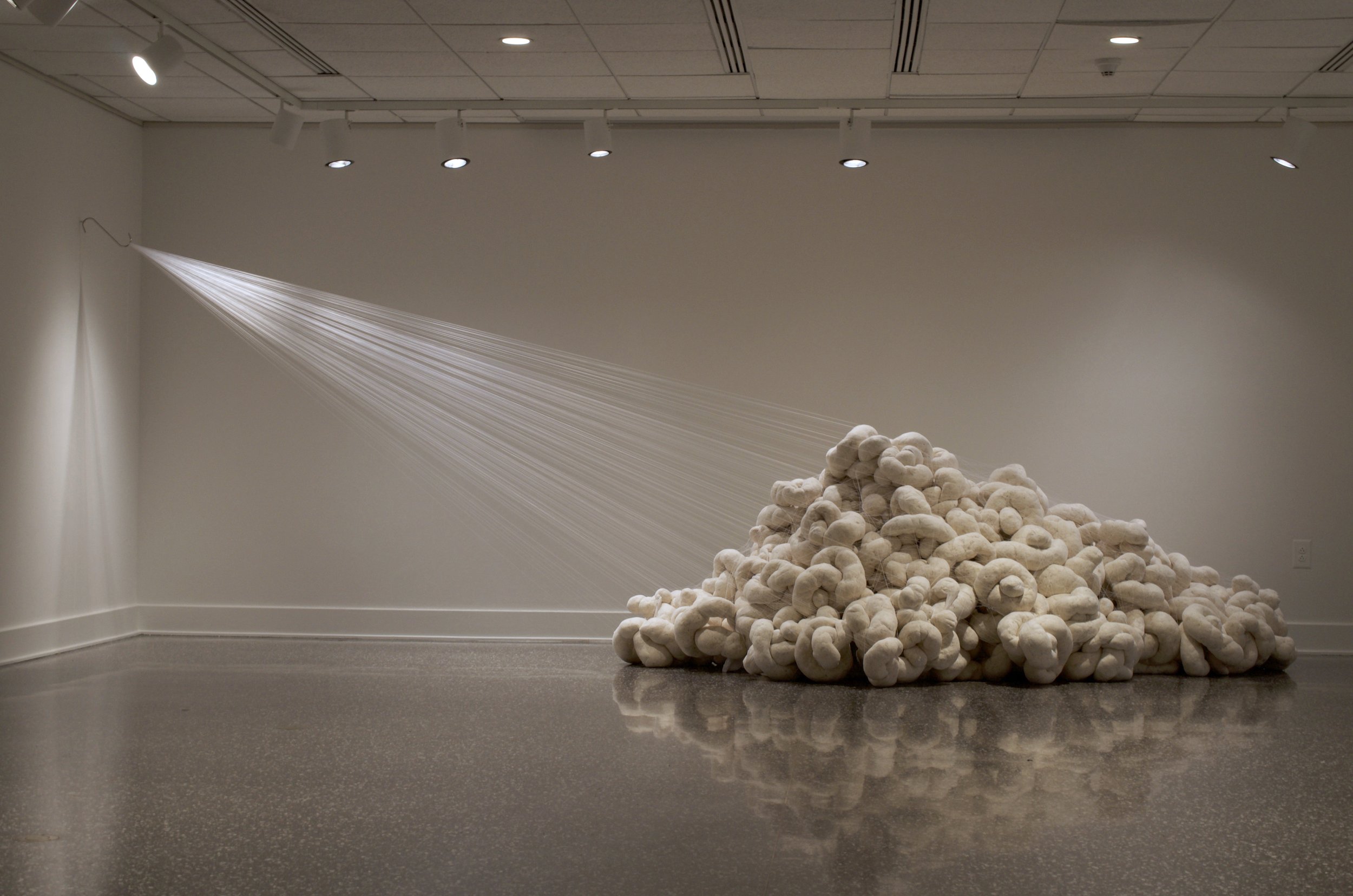

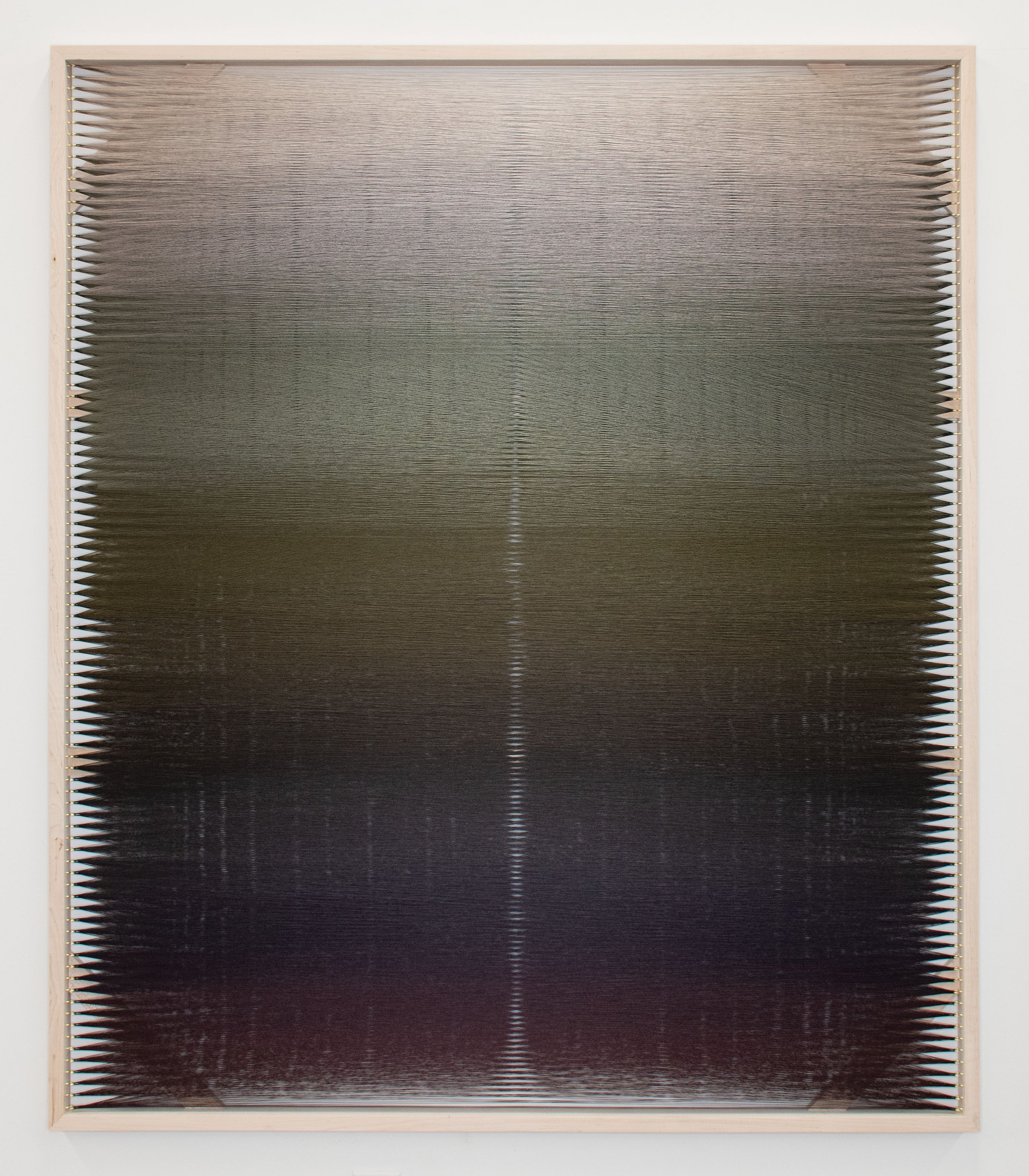

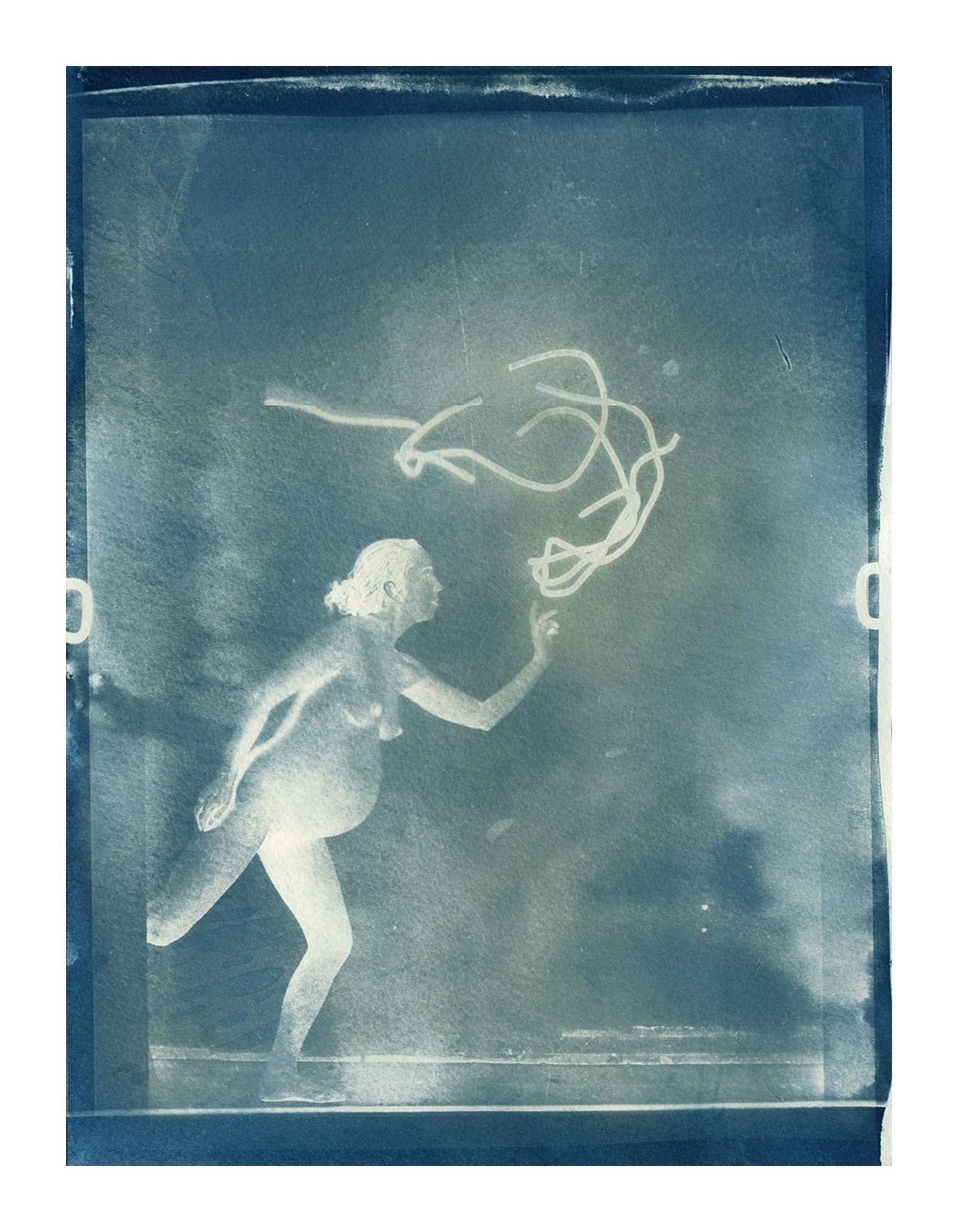

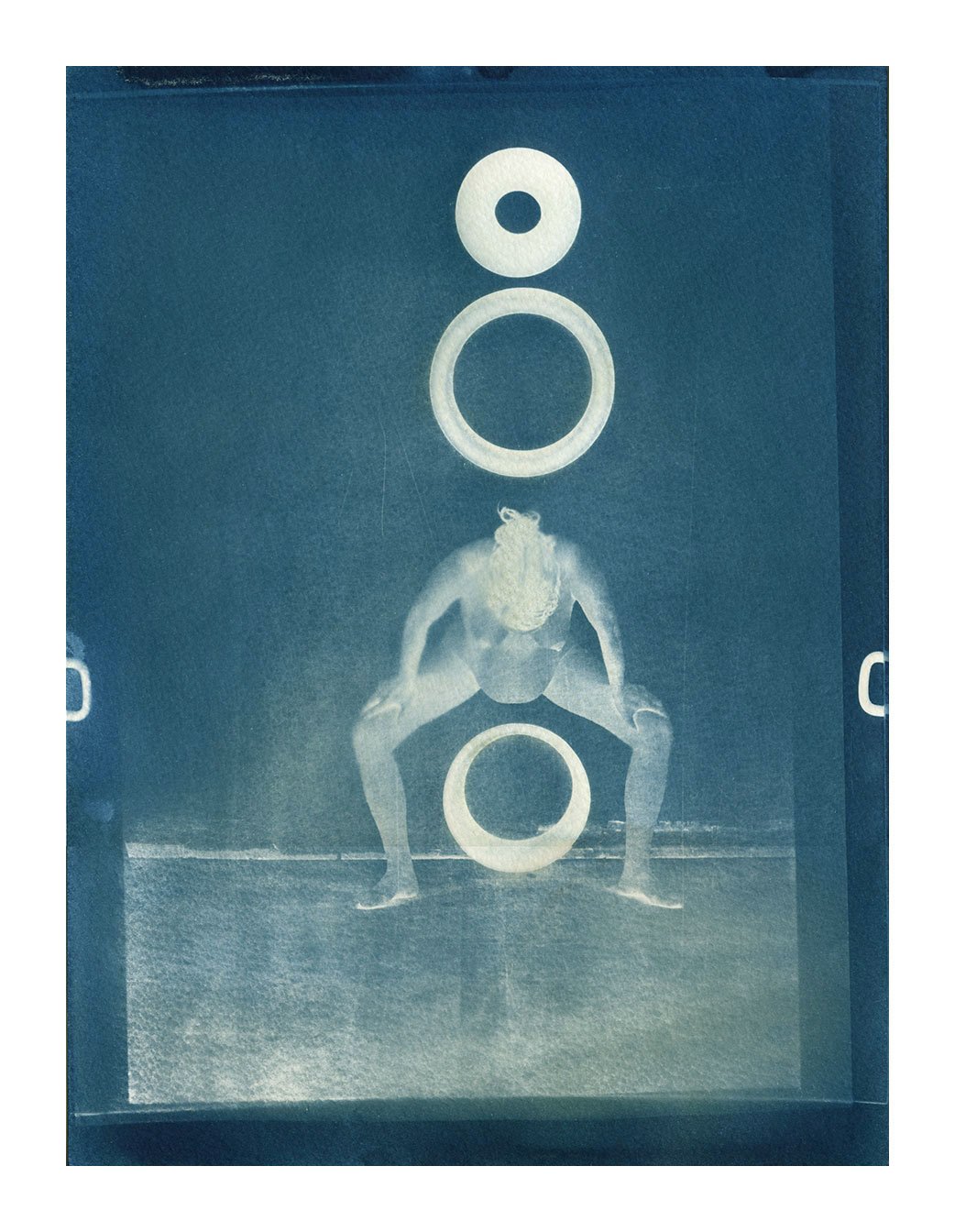

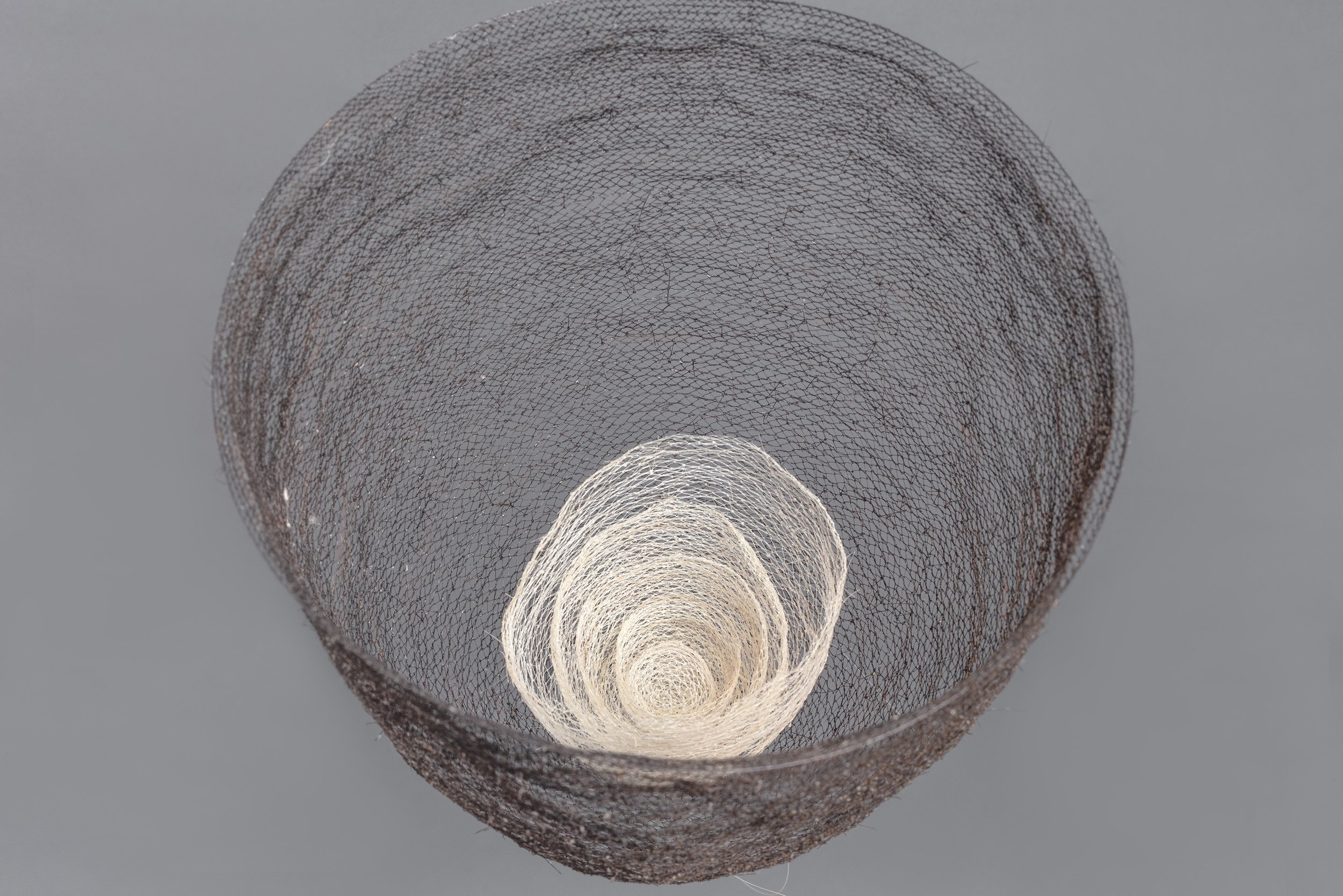

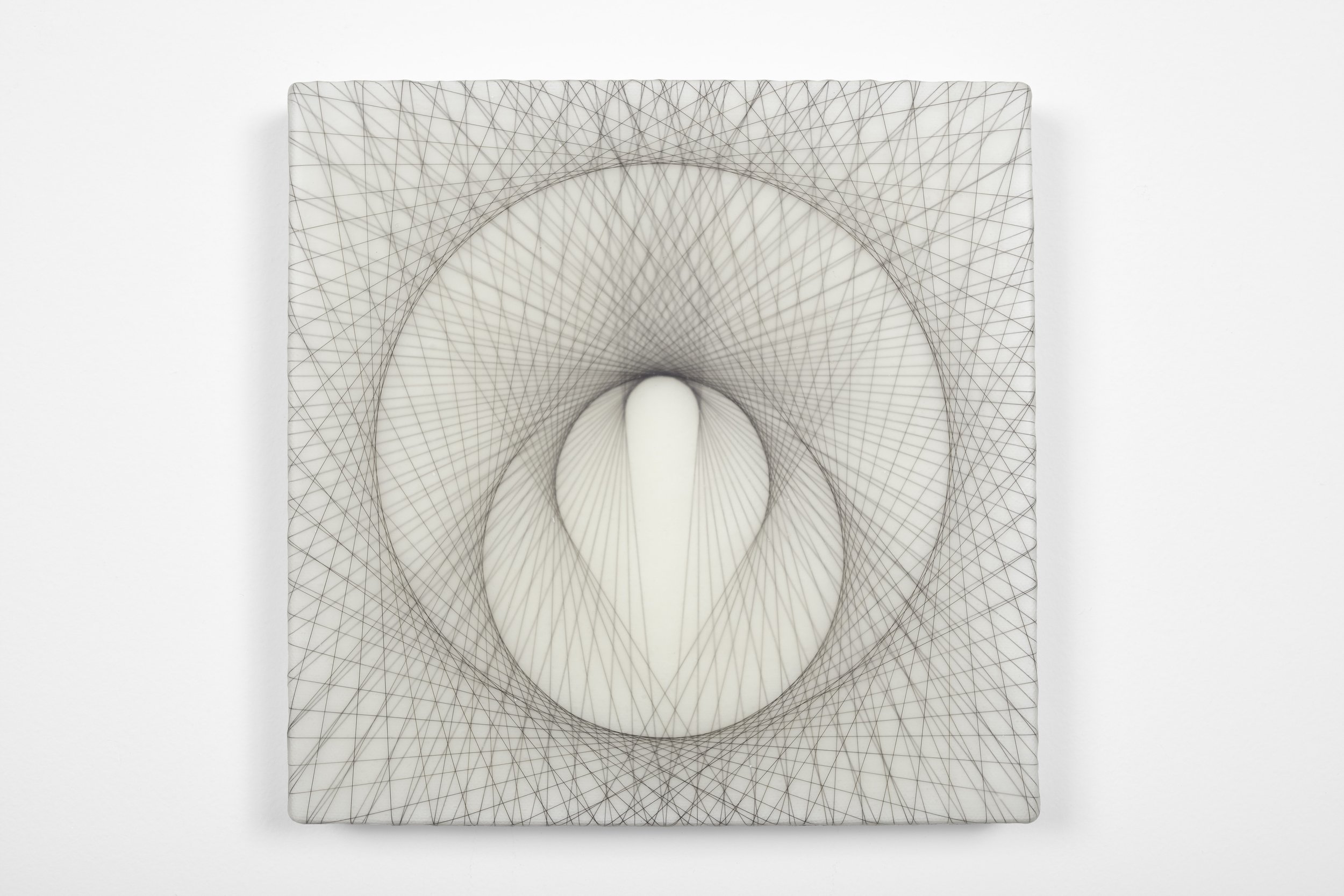

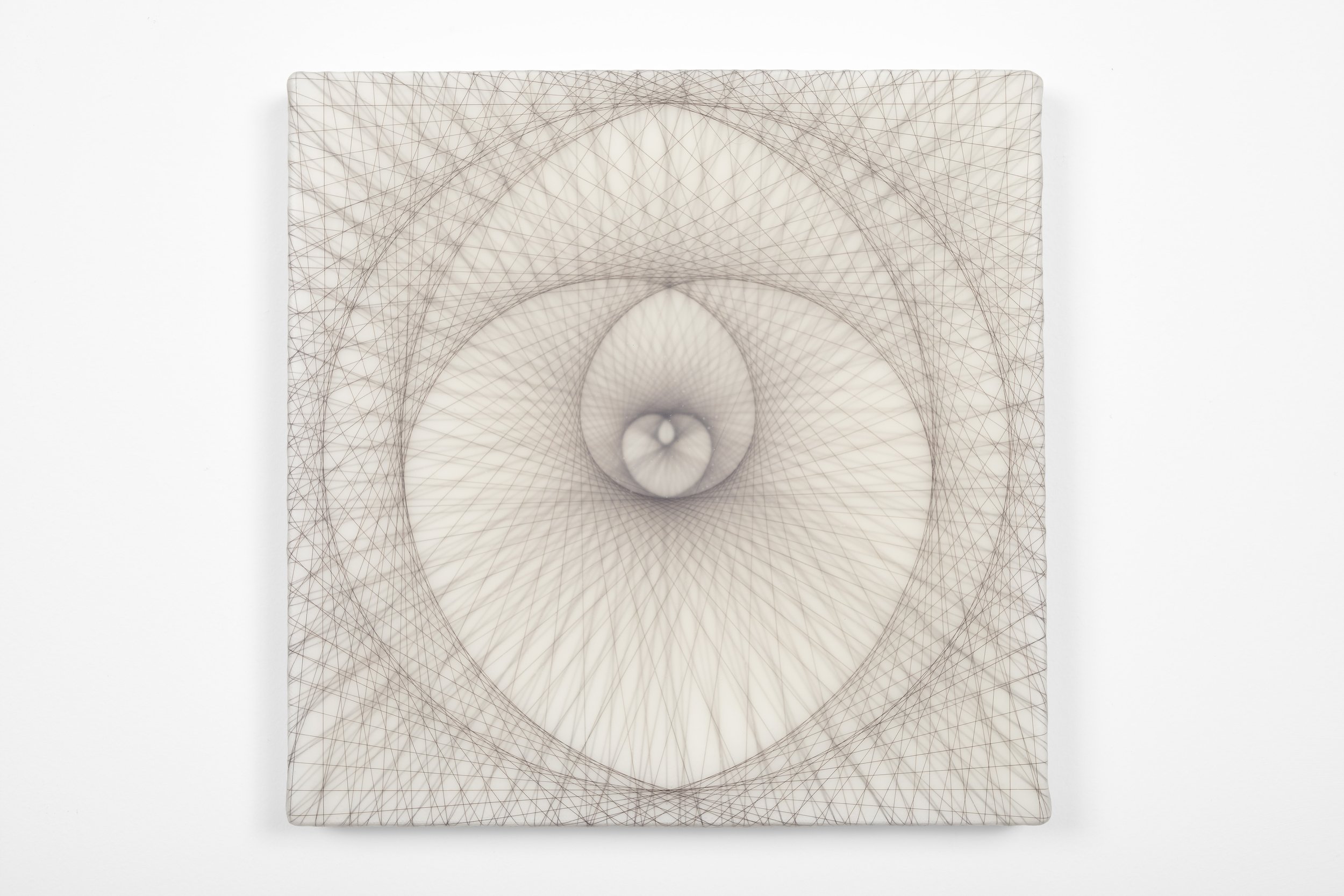

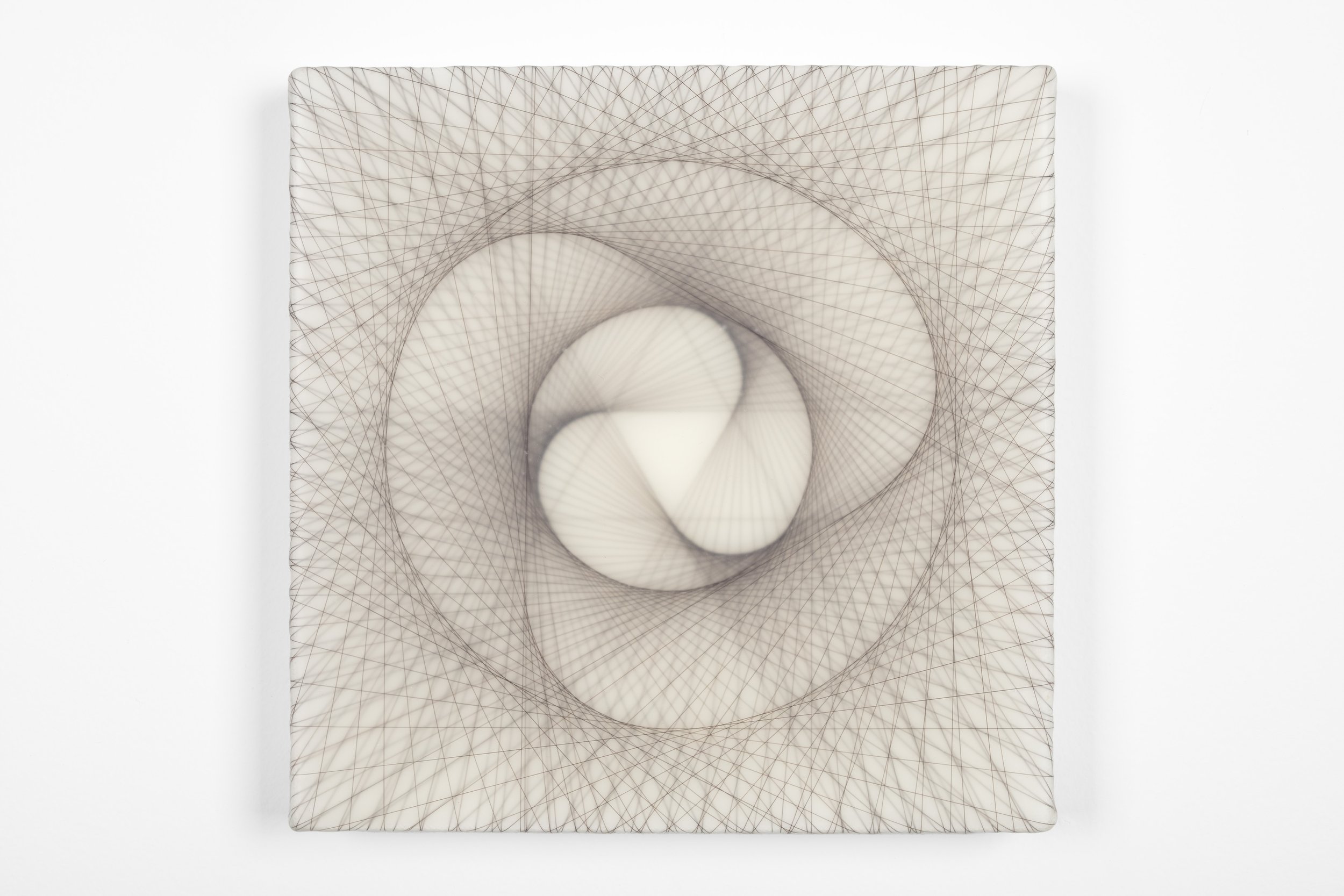

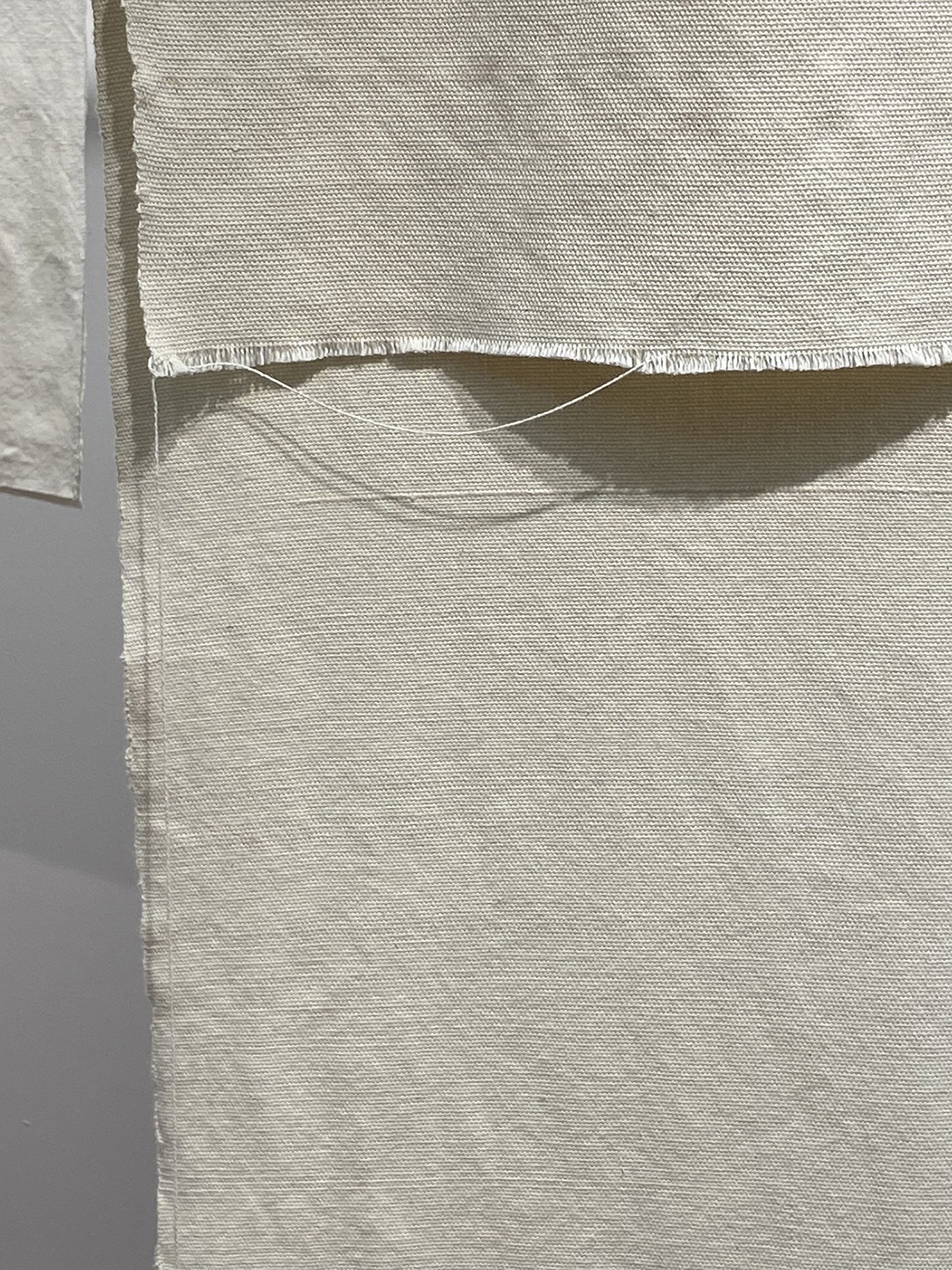

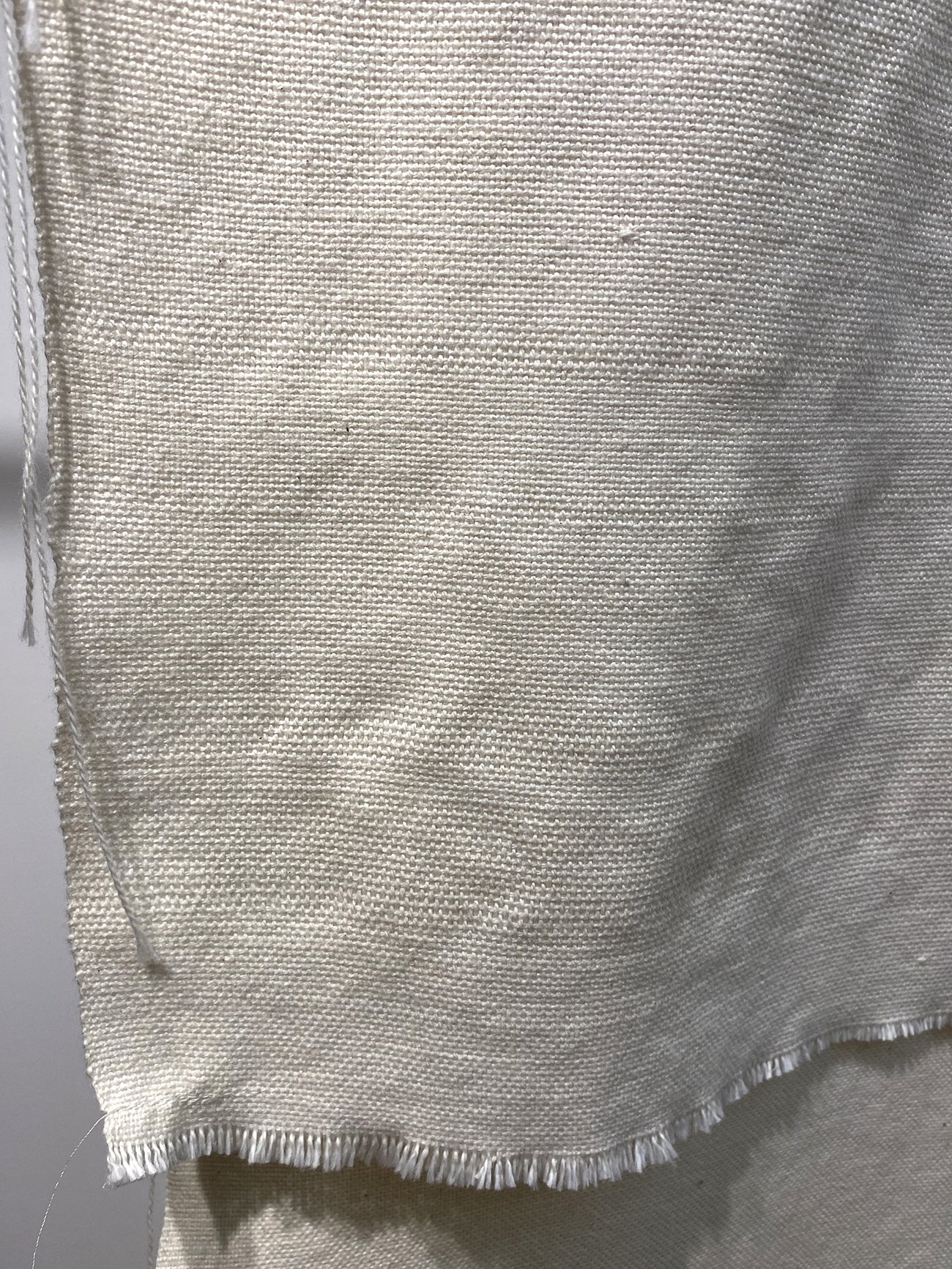

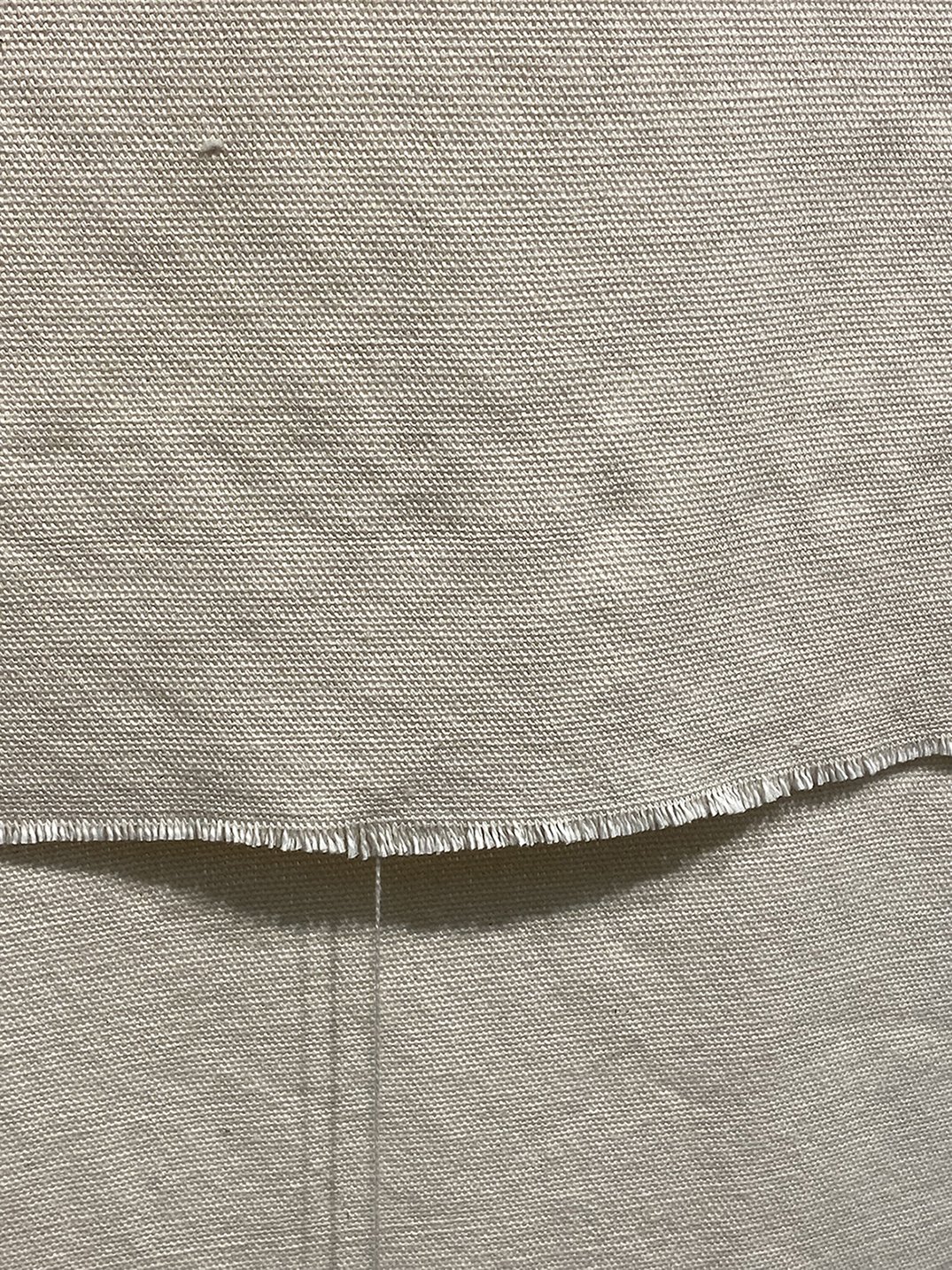

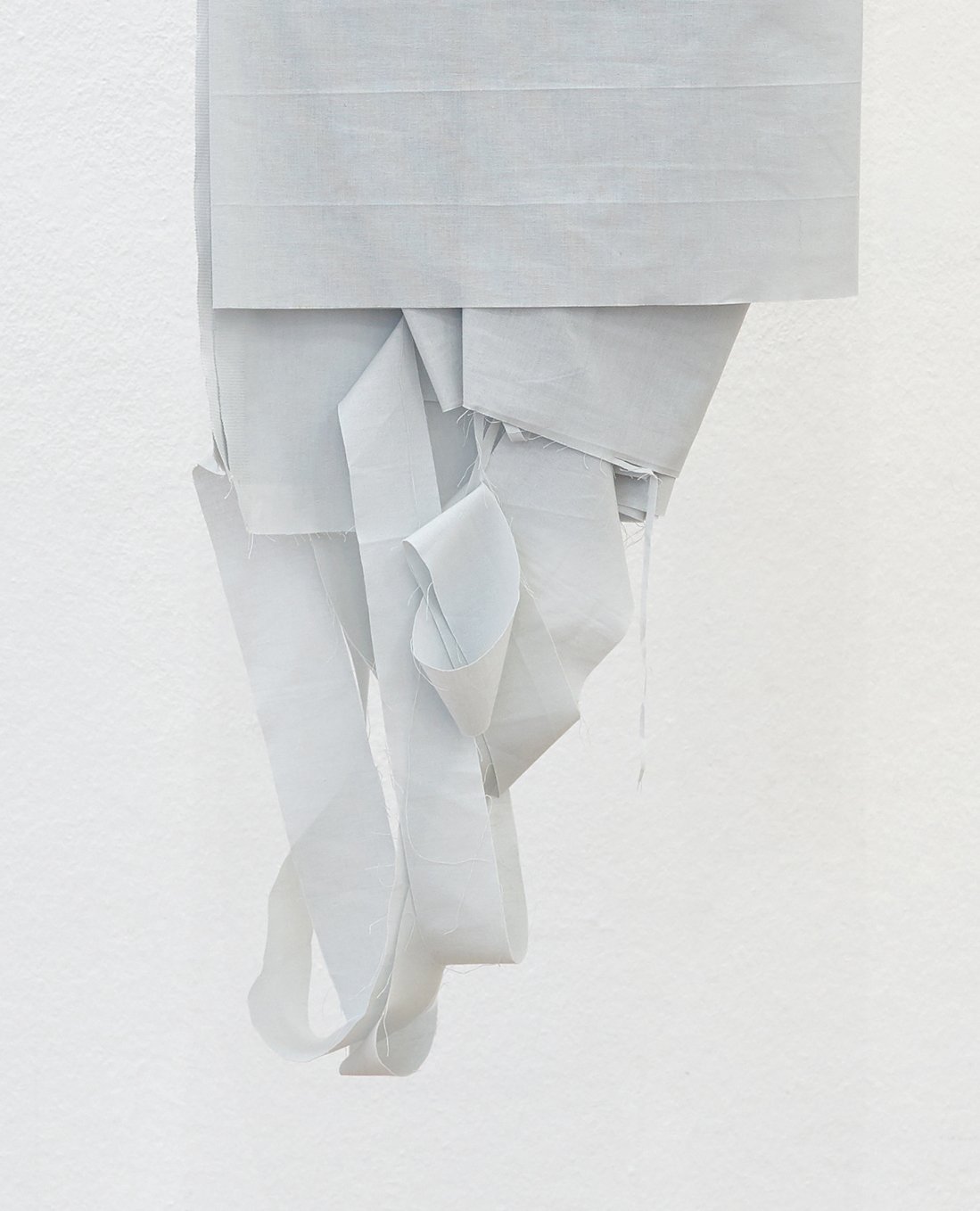

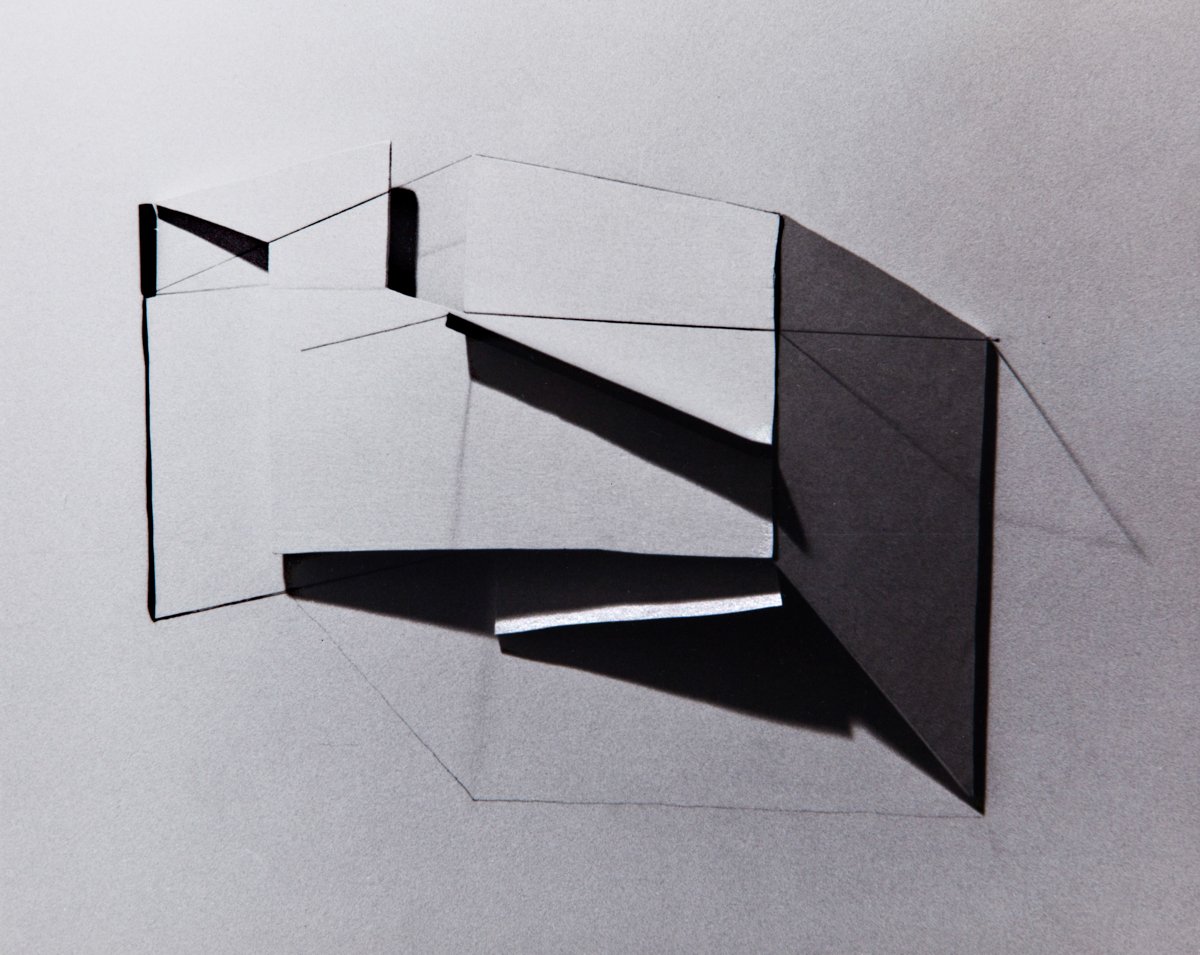

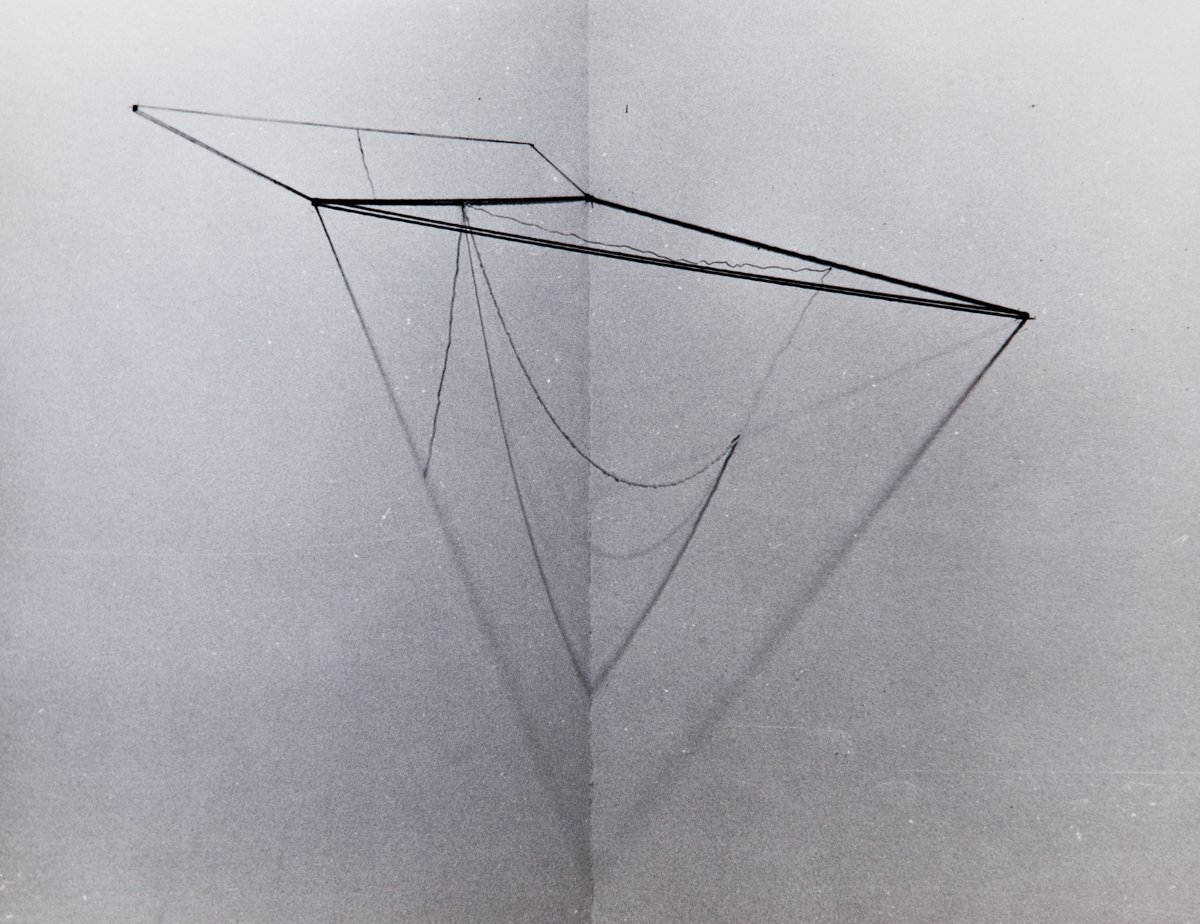

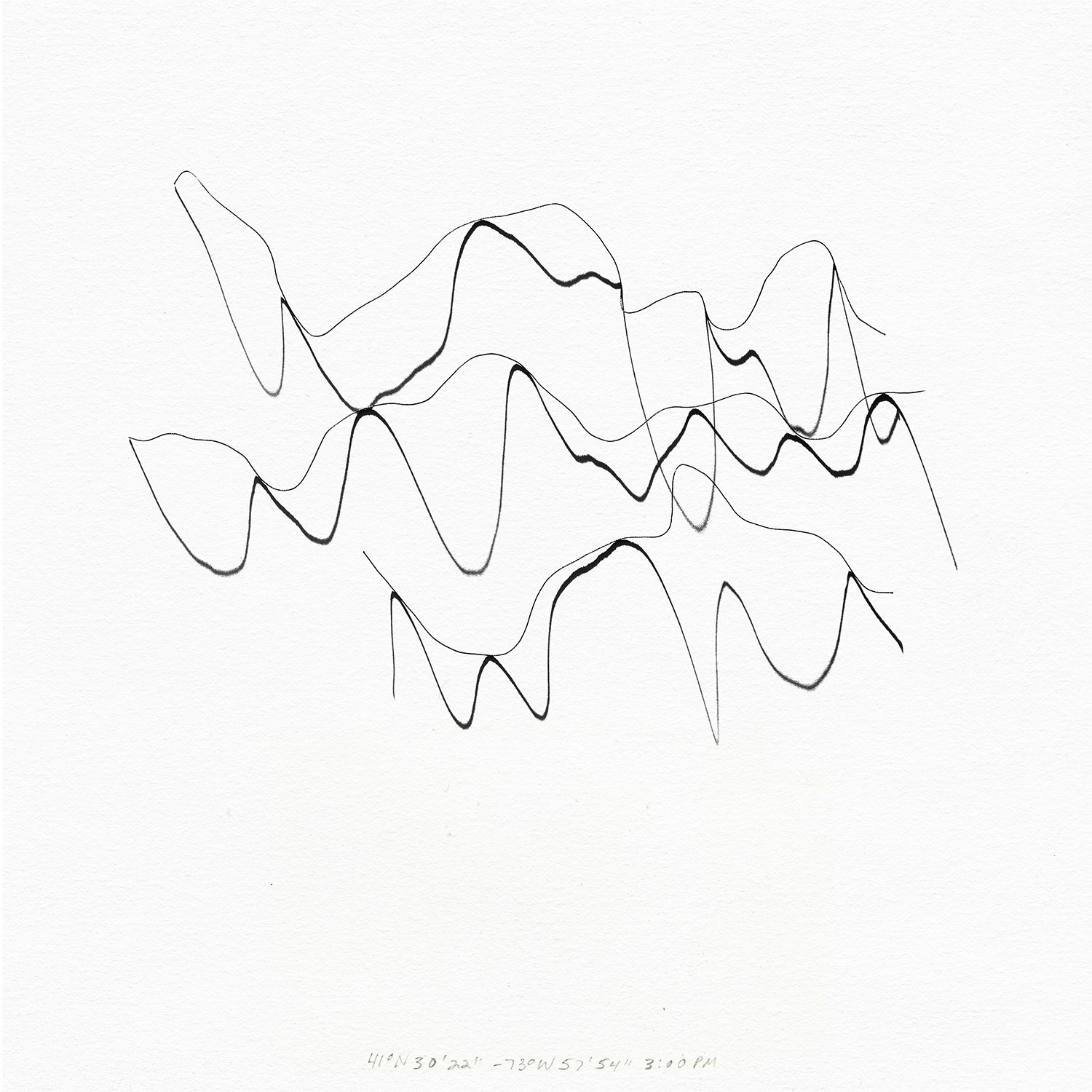

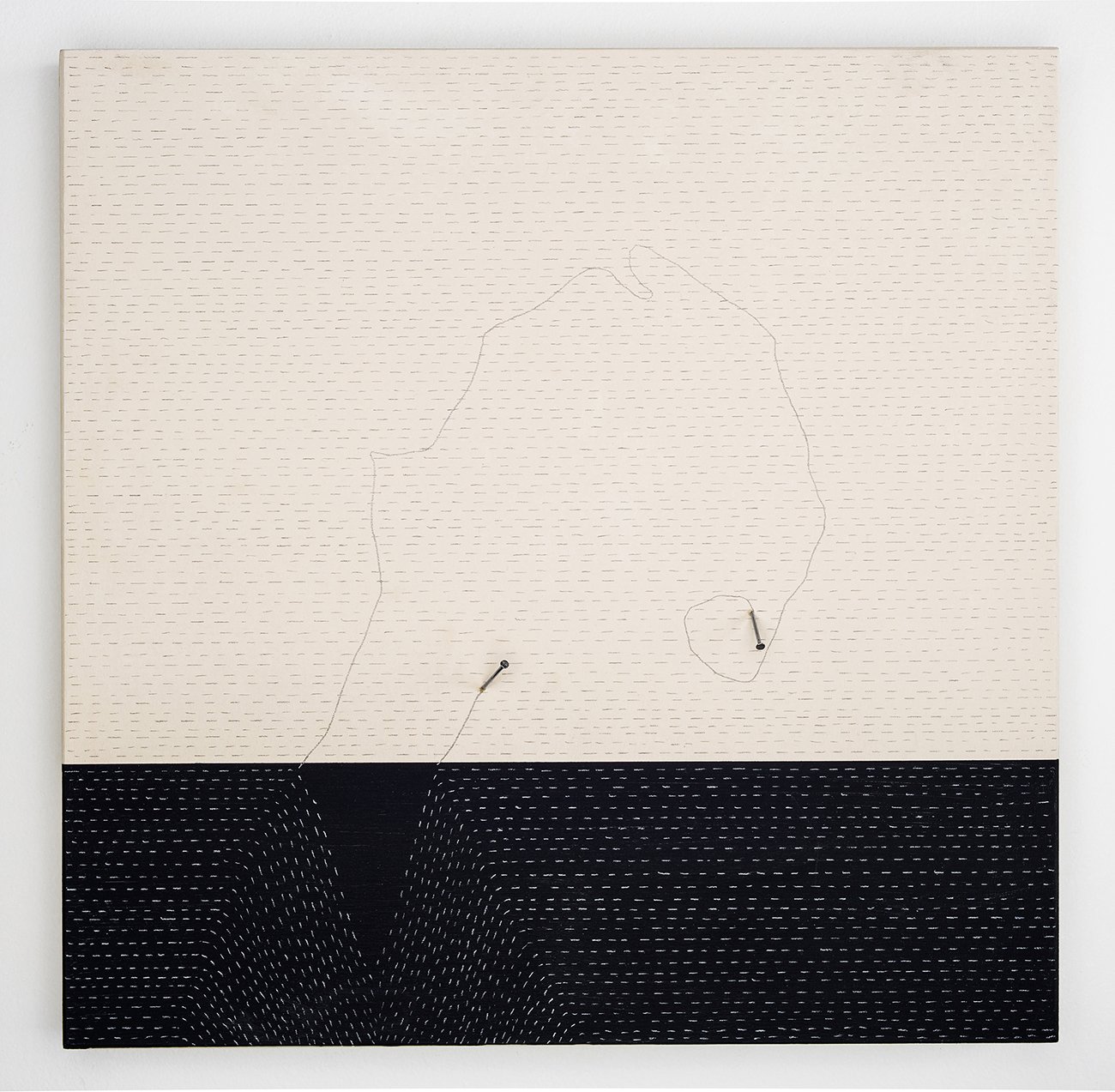

SW: I’ve always been interested in time, but it didn’t become part of my work until I moved to the Hudson Valley in 2008. I started to write the time of day on photographs that I took, and I felt like I was recording an energy or an instance of something. Then I had this moment in the studio when I was playing around with thread, and I noticed that the winter sun had cast shadows on the thread that was laying on white paper, and it looked like a pen and ink drawing. It was one of those amazing moments that you have in the studio. This moment was about time, the elements, the winter sun casting a shadow, and the object becoming a sundial. From there I started to research the recording of time, and began to think about everything as a type of sundial.

MH: So it sounds like you had been vaguely interested in time, but then you had this epiphany around it, and your interest expanded.

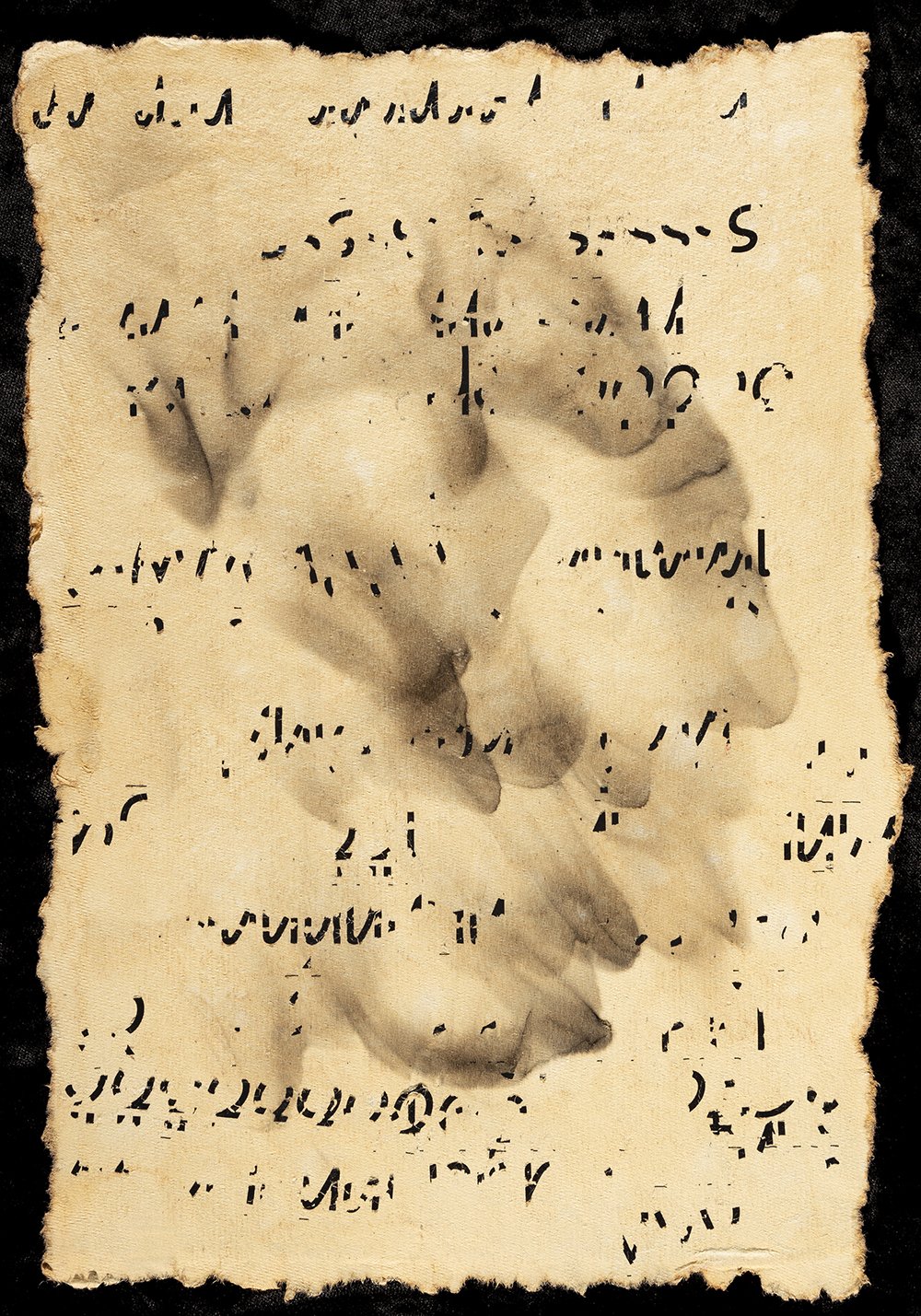

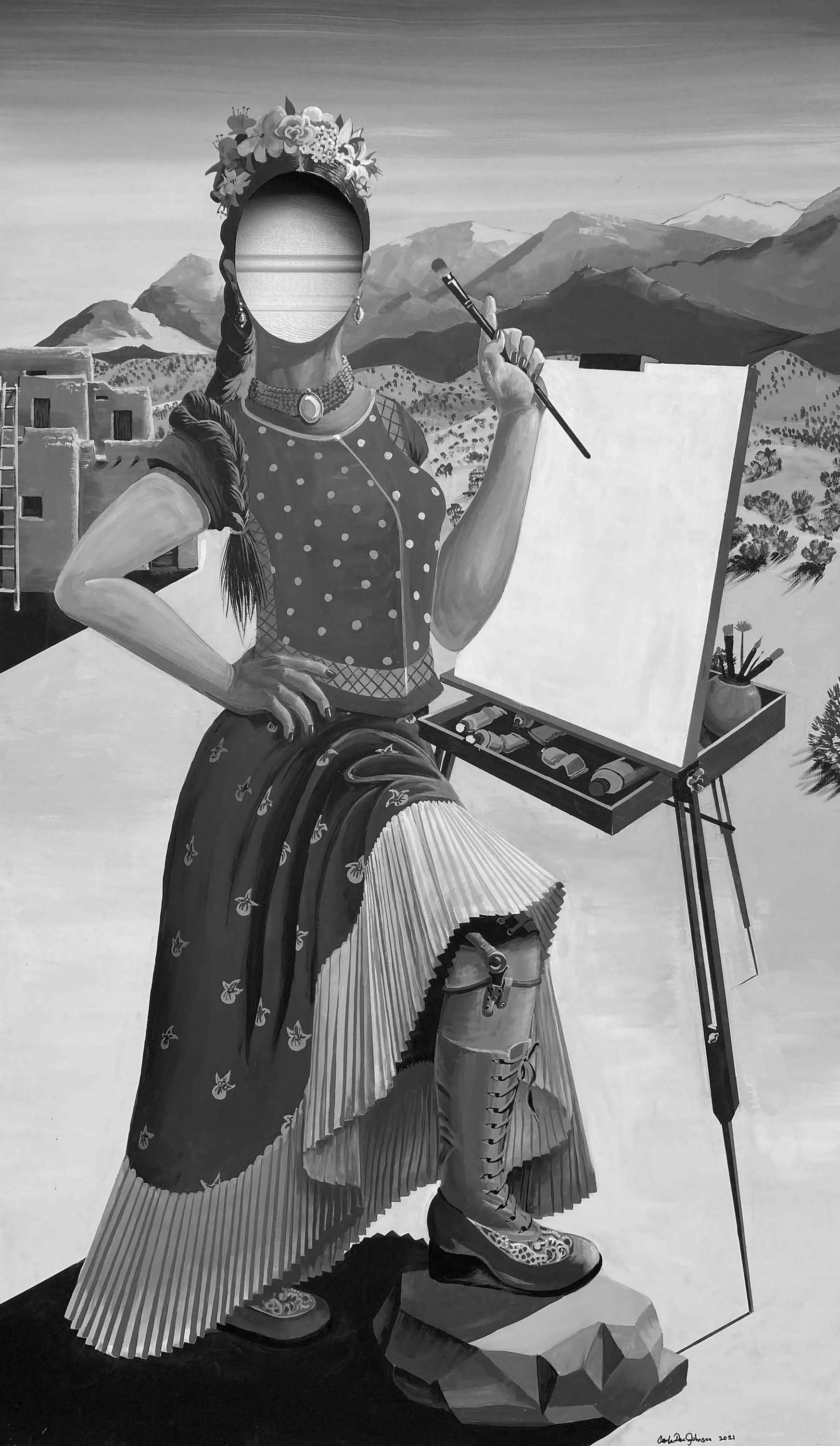

SW: Yes, it was a super-epiphany, and I had a strong feeling that it was the beginning of my work changing in a big way. Prior to this, when I was living in New Mexico, my work was more about politics and the female body. When I moved to New York City, I was taking photos as a way of sketching, but that work was no longer important to me. So this new direction was really exciting.

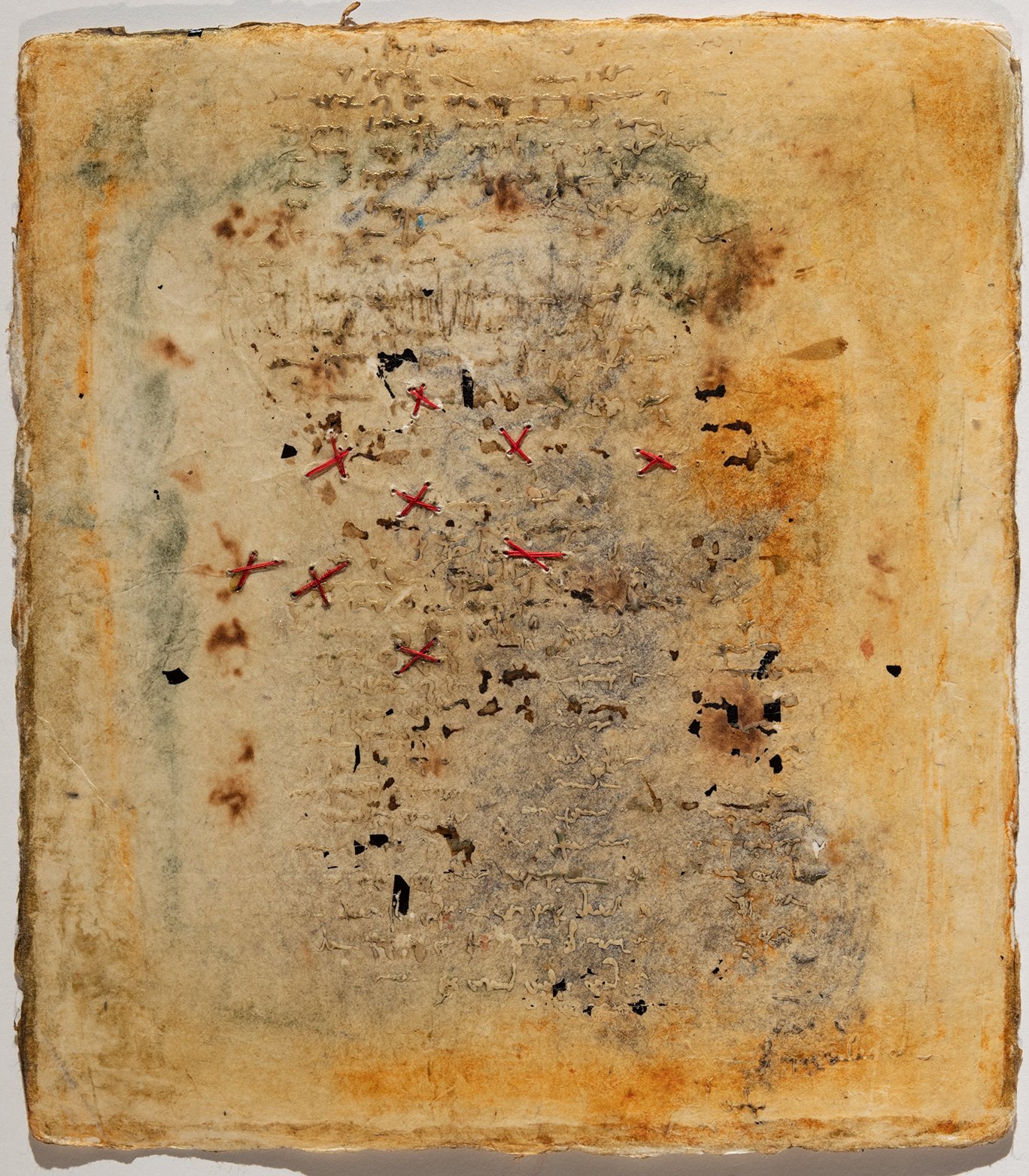

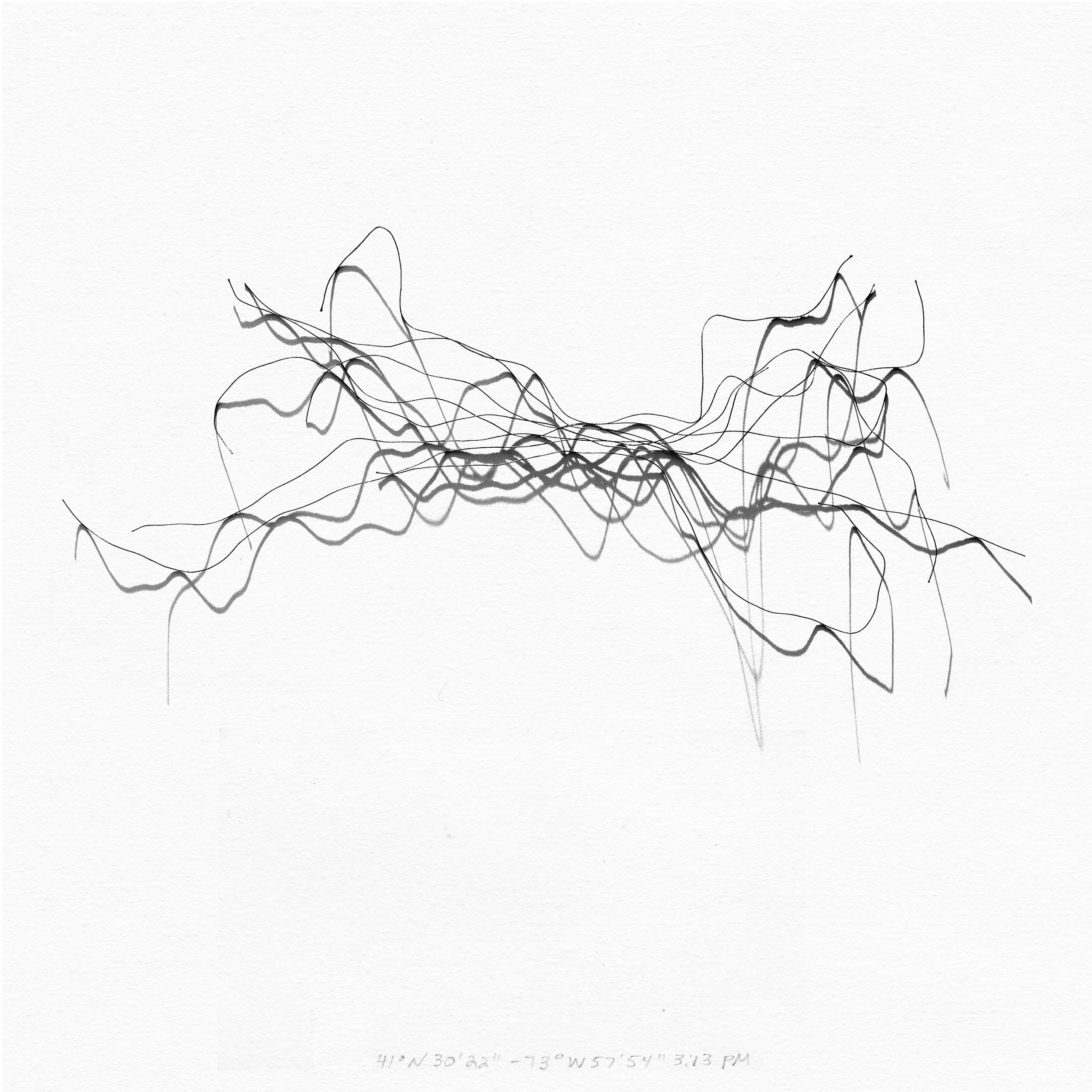

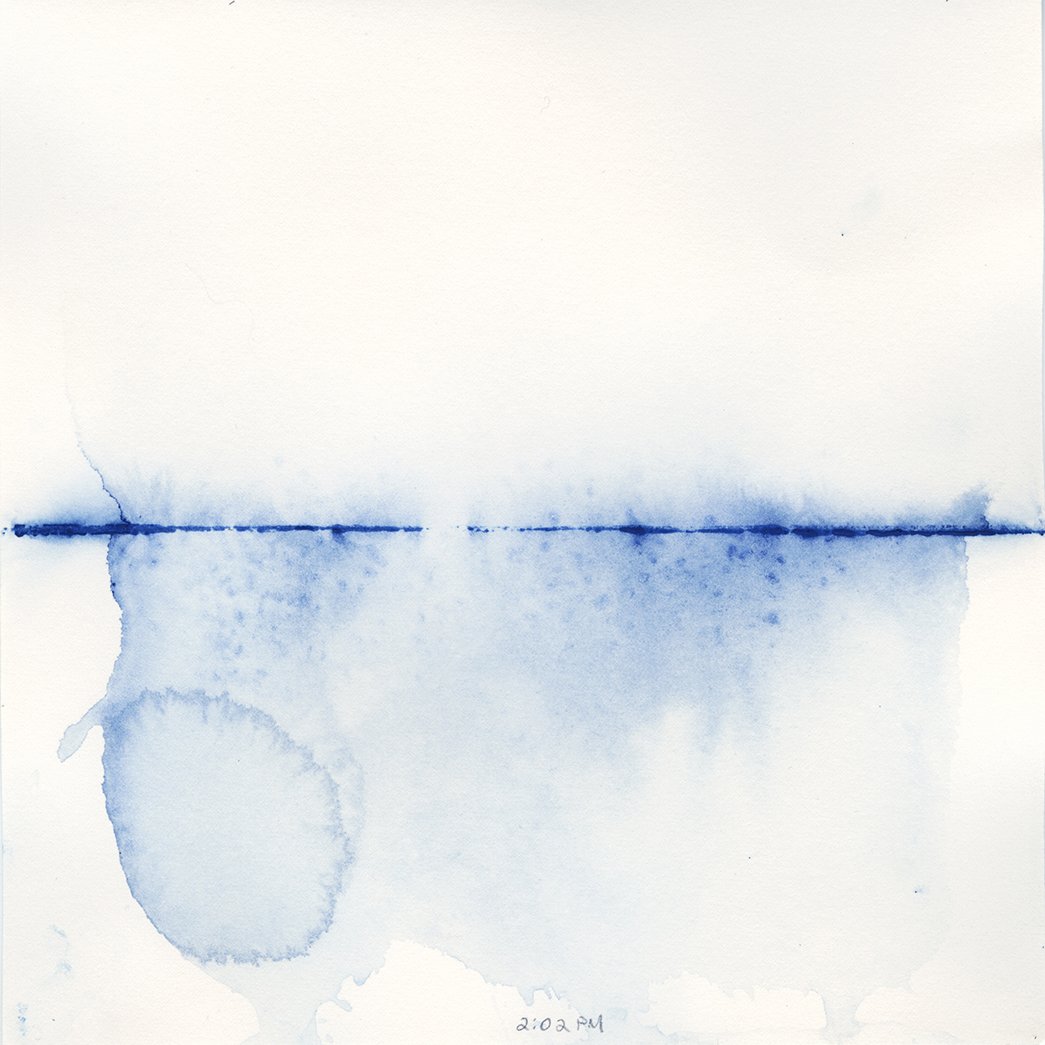

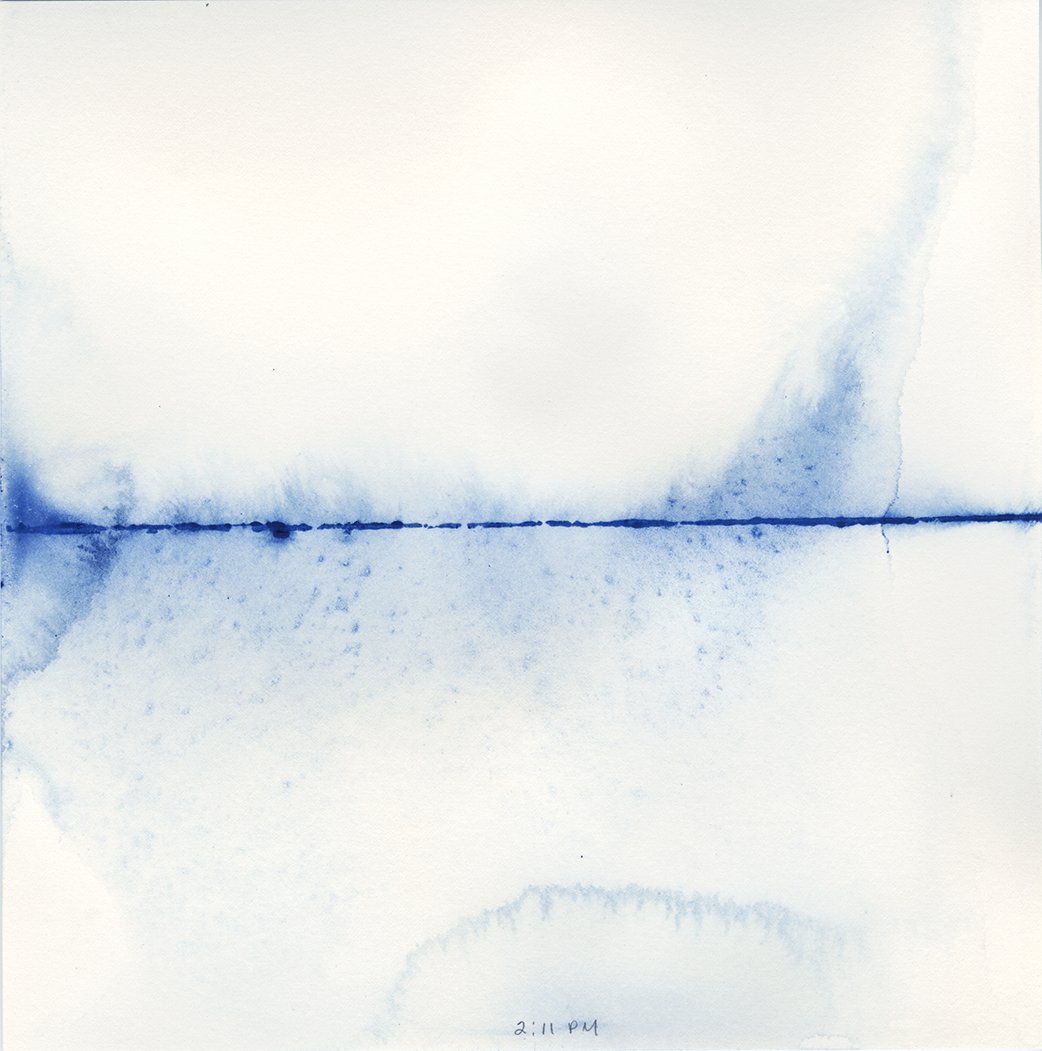

MH: You meticulously mark the passing of time by using nature-based processes: sunlight, shadow, wind, rain, waves. In one series, a wave crashes onto a piece of paper and leaves a mark. You then record the precise time that the mark was made. Why are you interested in recording the exact moment of an occurrence?

SW: It’s about where I am at the moment that I connect with this natural object or event. It’s like I’m the recorder of myself in connection with the elements. This happened, and I was there. It becomes a collection of these moments and where I was in the world at that moment. It’s also a moment of dissolving with that thing, with the rain, and I become very present.

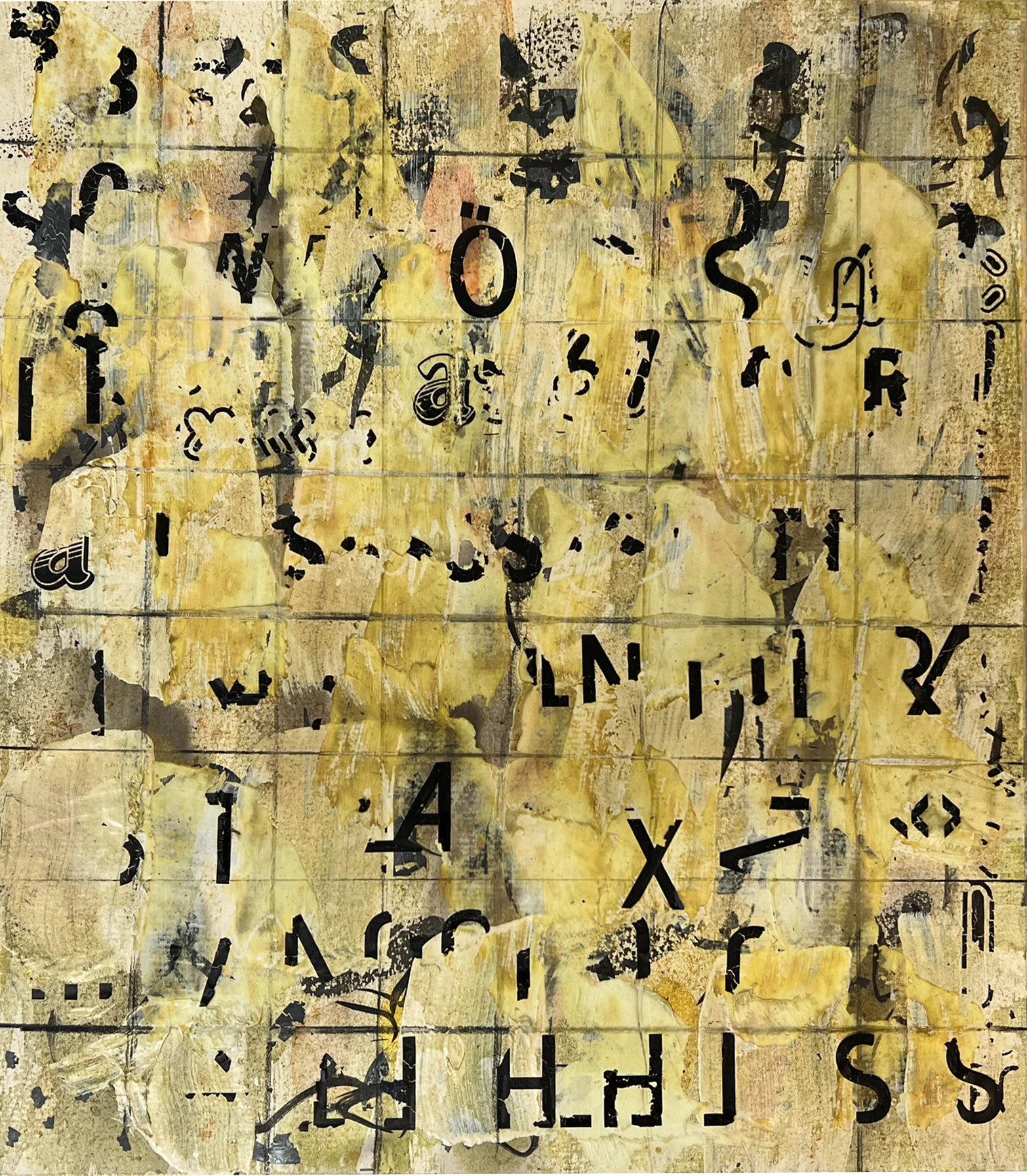

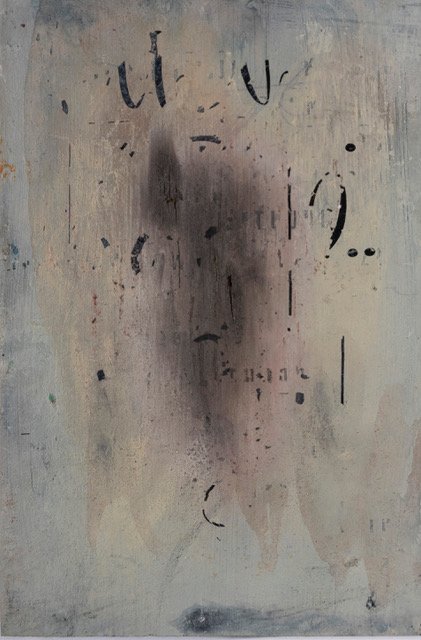

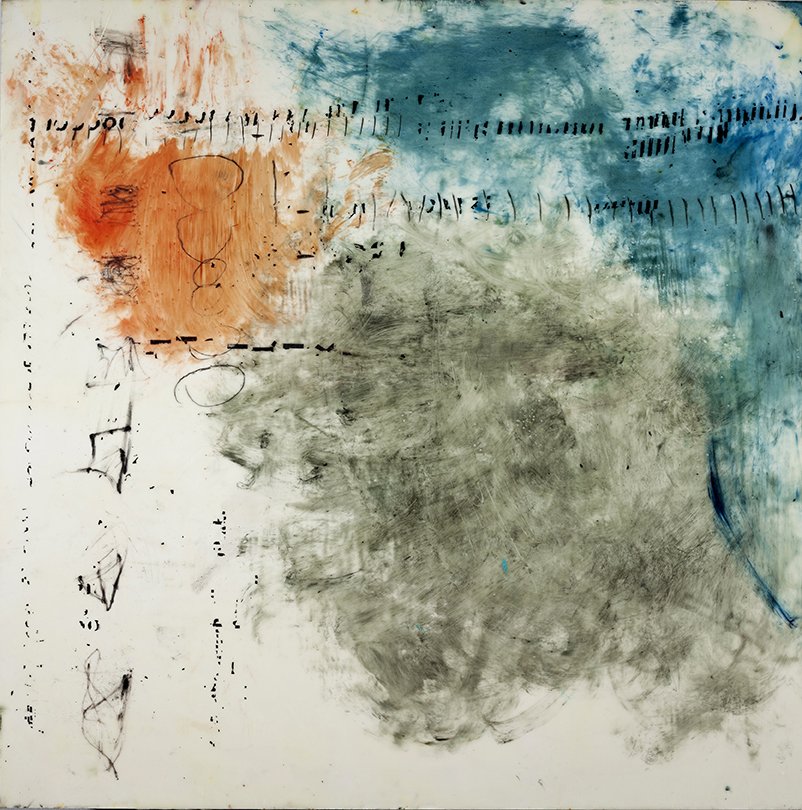

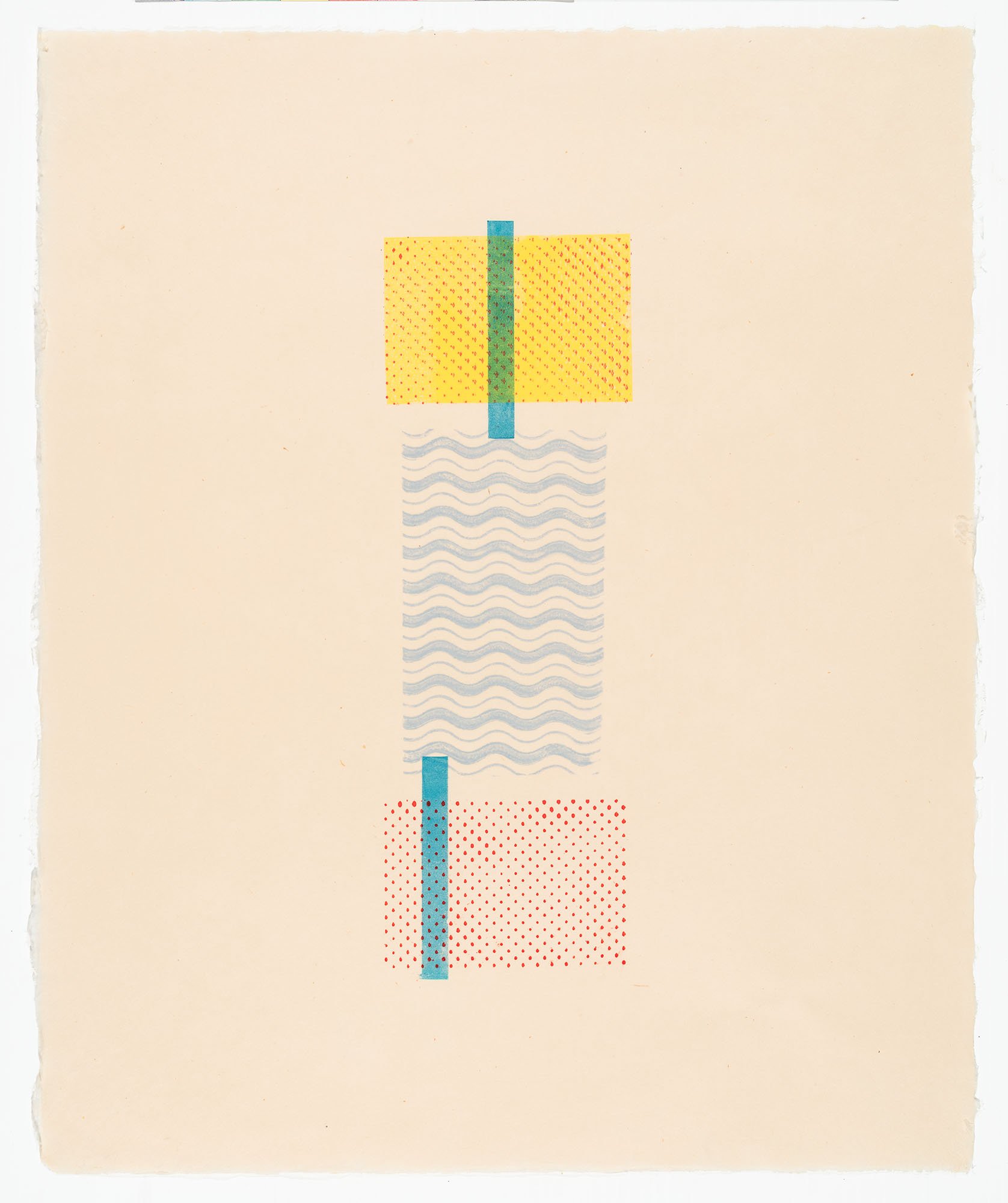

MH: I’d like to dive into your process to understand it better. In your series Rain Drawings, you place pigment on a sheet of paper and leave it outside in the rain, which pelts into the pigment and leaves a mark. Do you attempt to regulate or edit the drawing in any way, or do you leave it entirely to the elements?

SW: It’s pretty much up to the elements. The part when I’m involved is when I decide that it’s done. So the date and time that I put on the rain drawing is the moment it began, then I stand there, getting wet and watching the rain do its thing. It’s just wonderful to watch the rain disperse the paint, then when I decide it’s finished I carry it inside and it takes 24 hours to dry. And during that process it continues to become something else, because it changes as it dries. It’s a beautiful process.

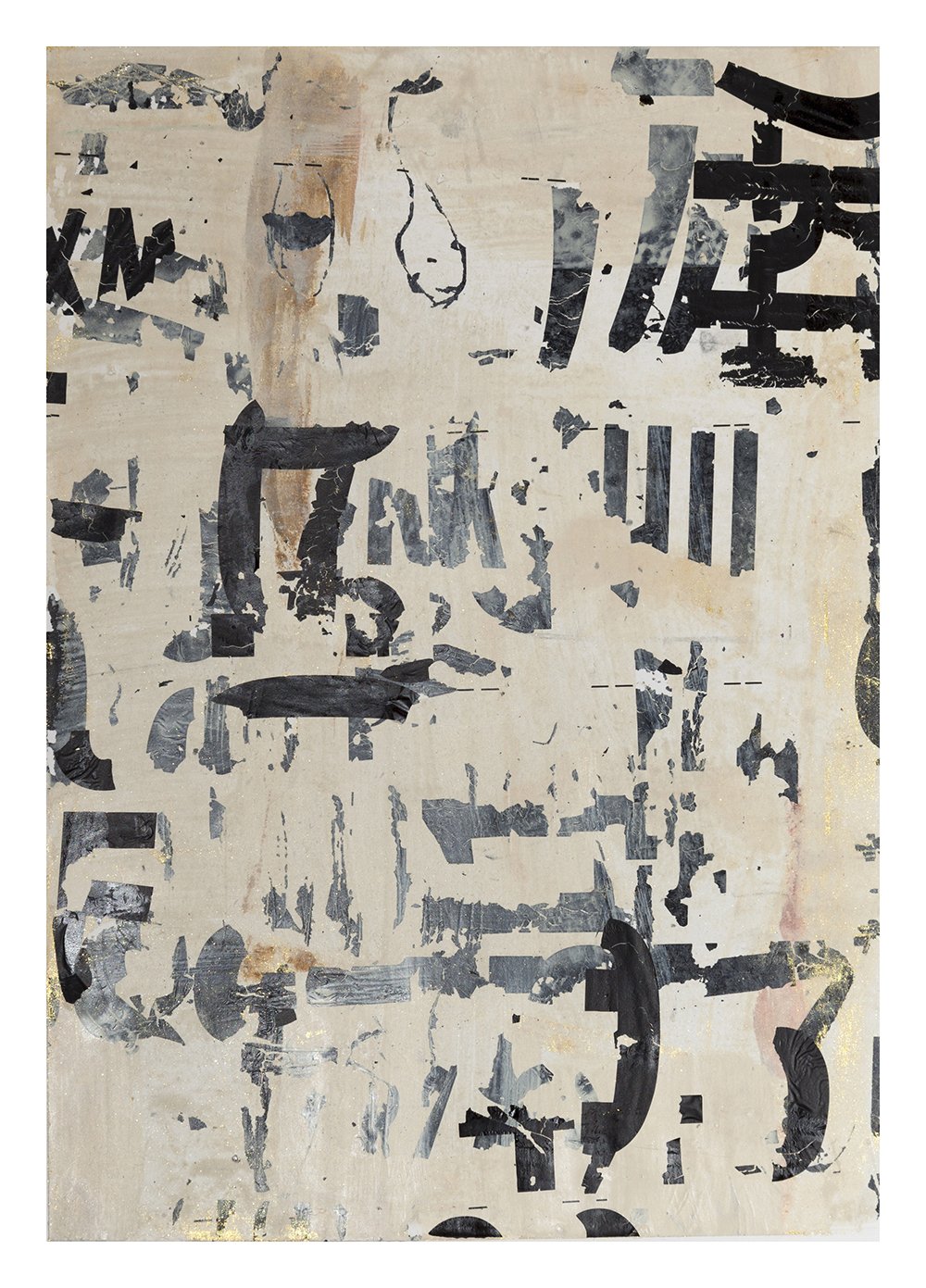

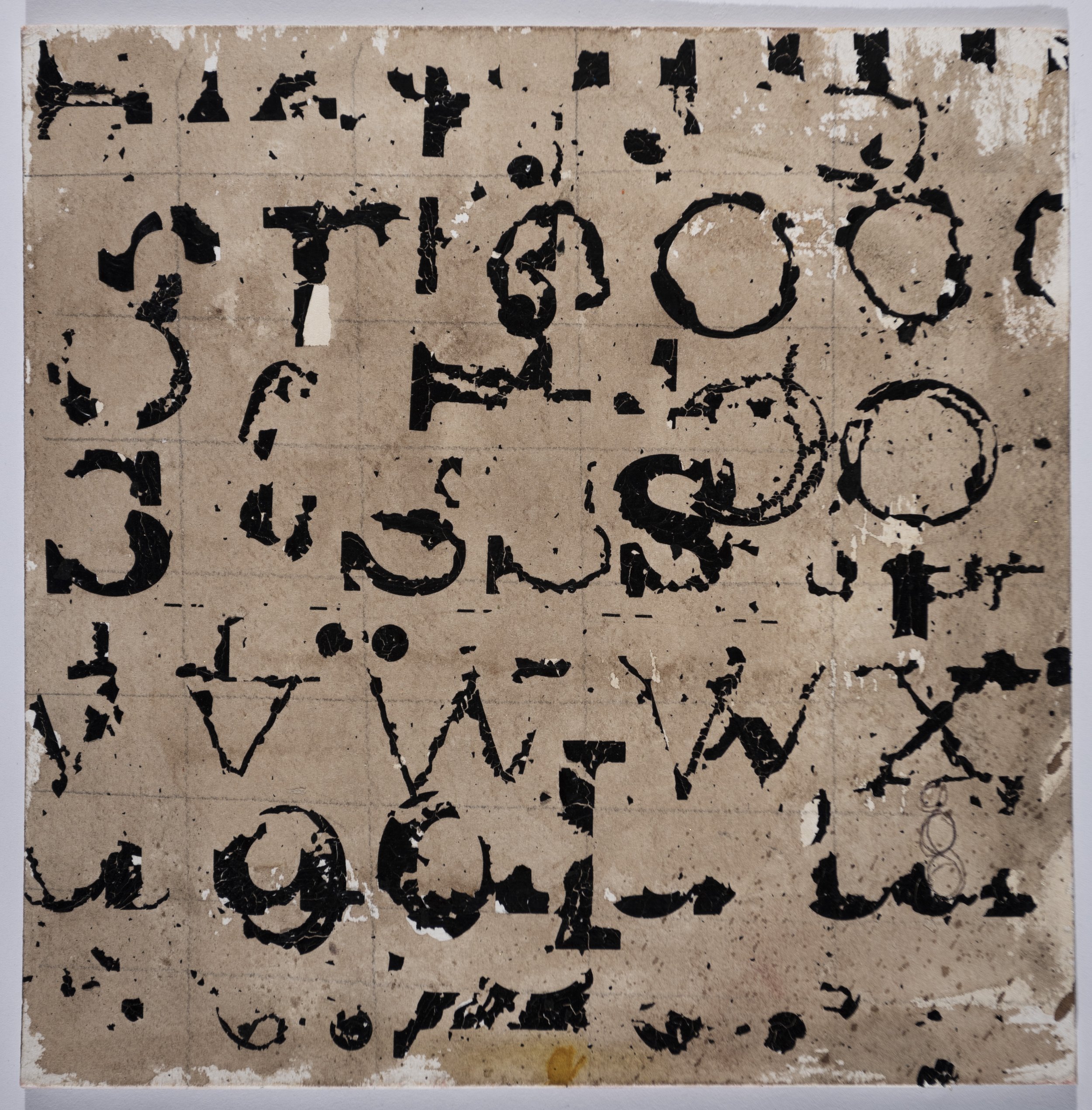

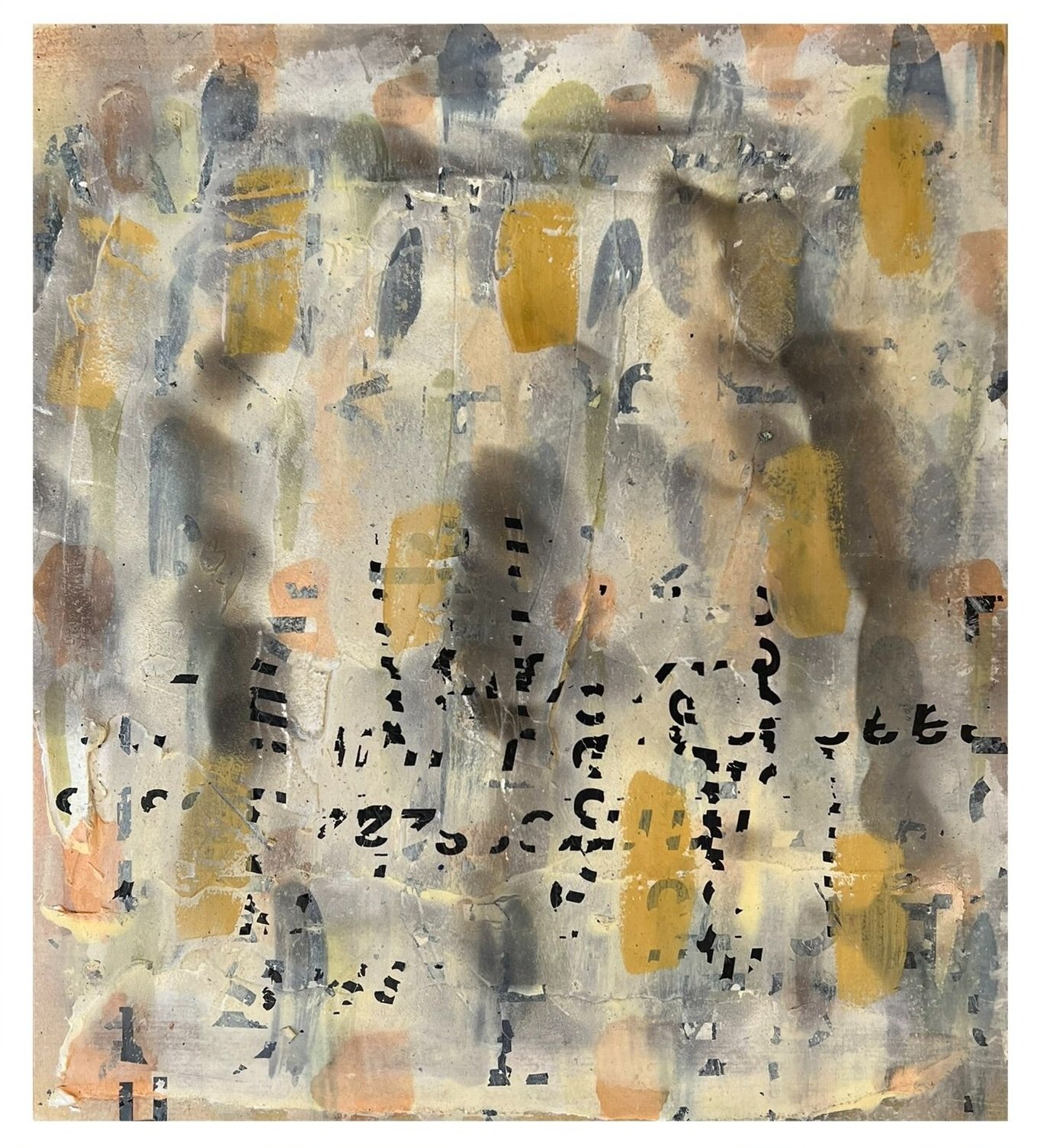

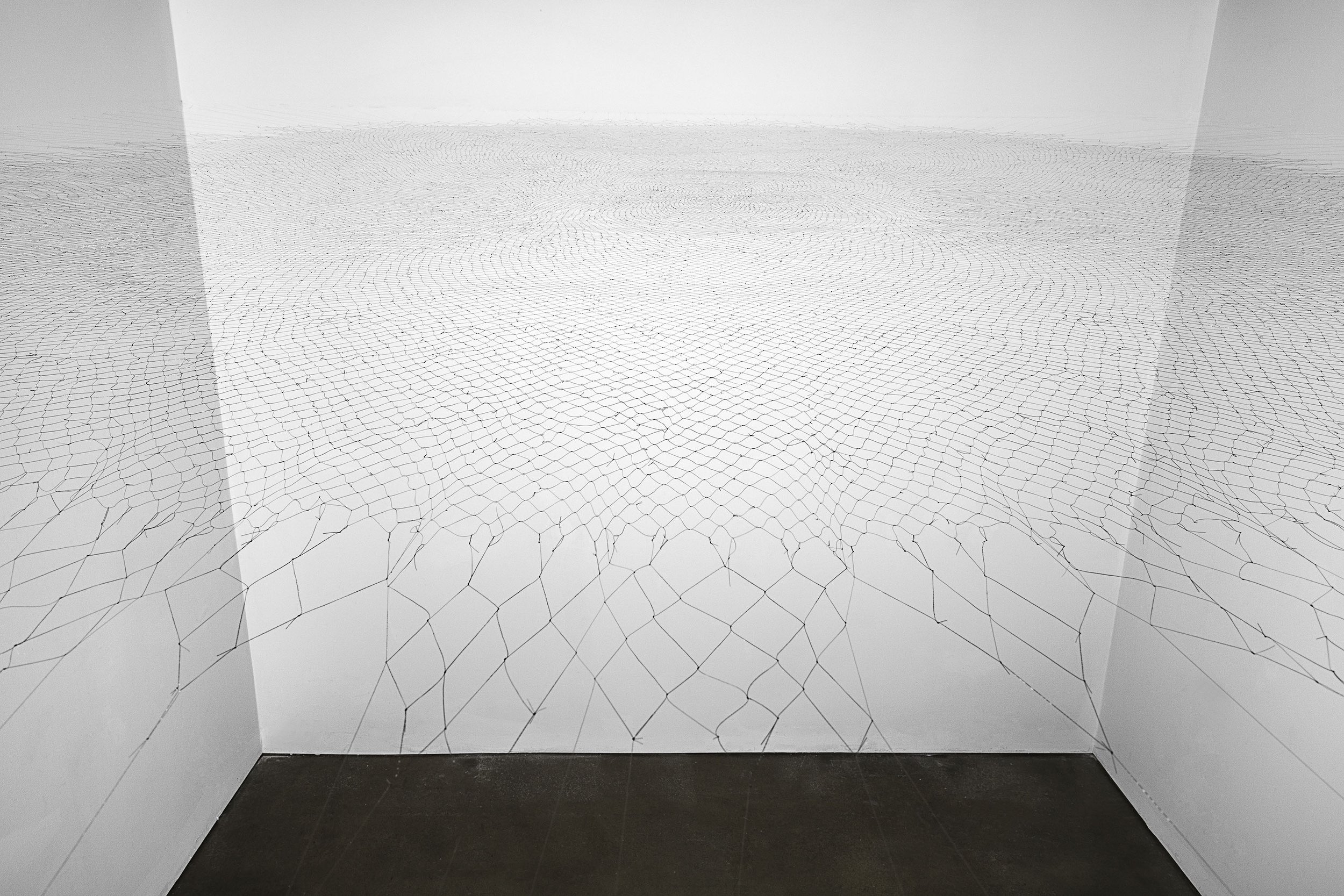

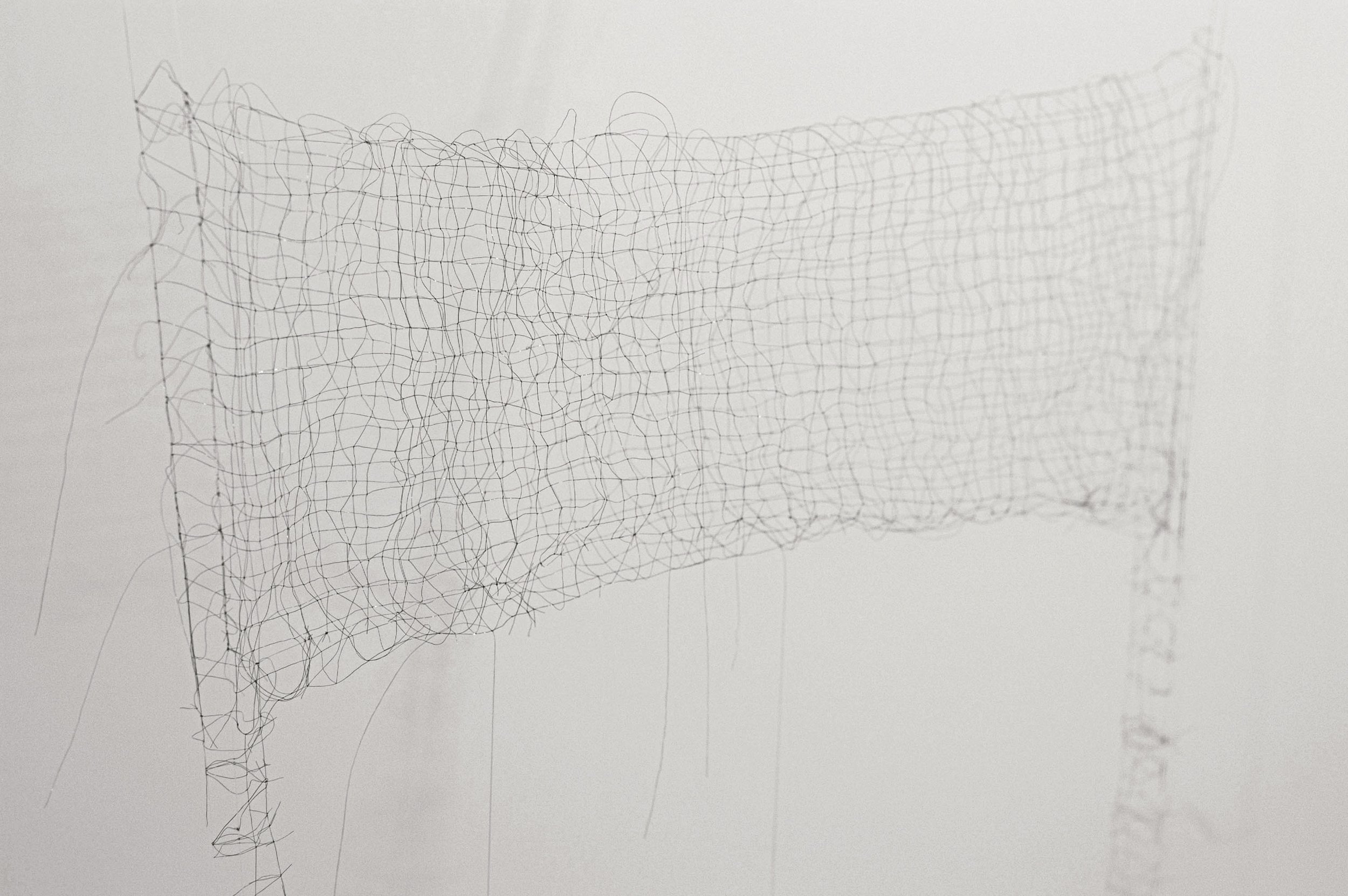

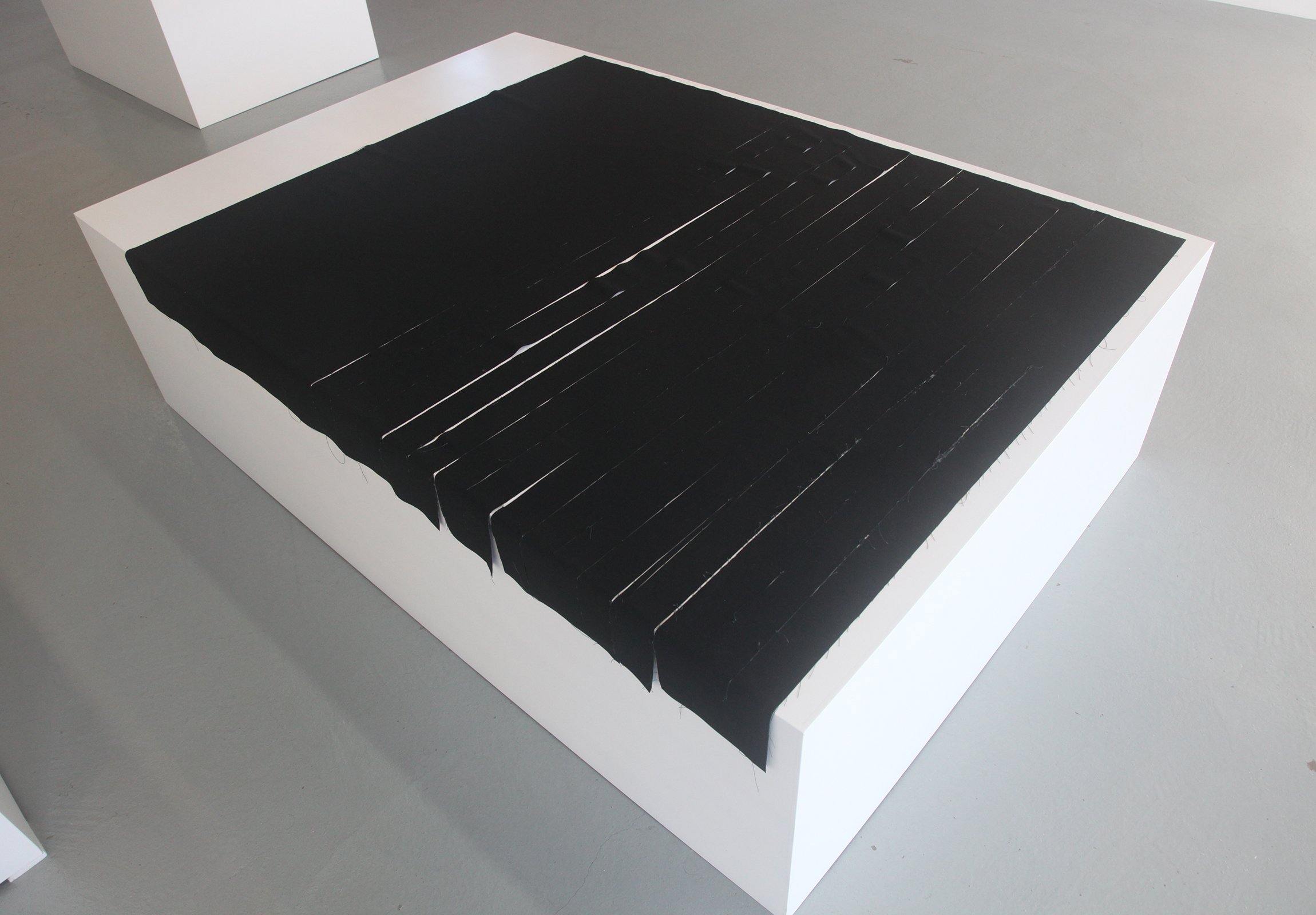

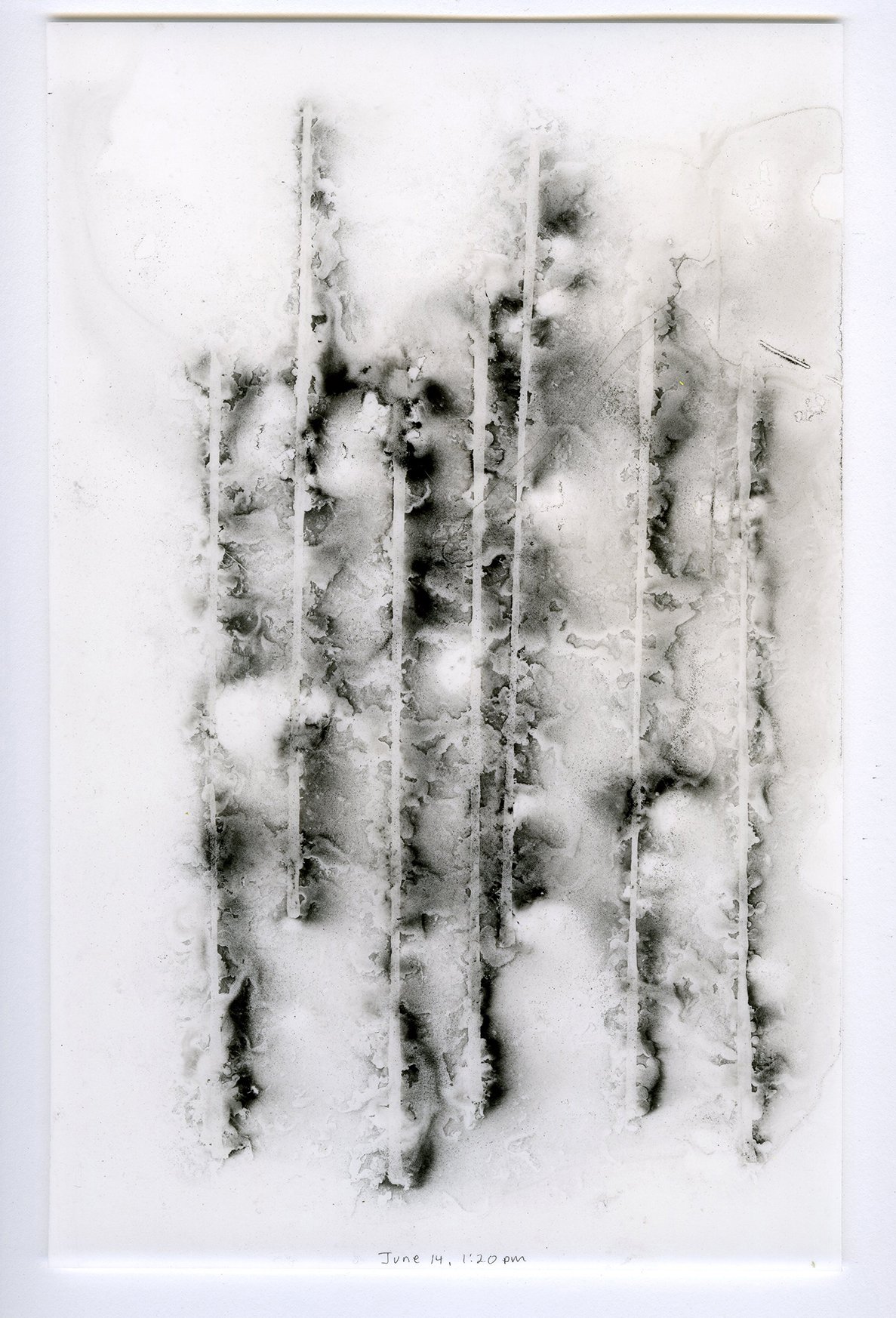

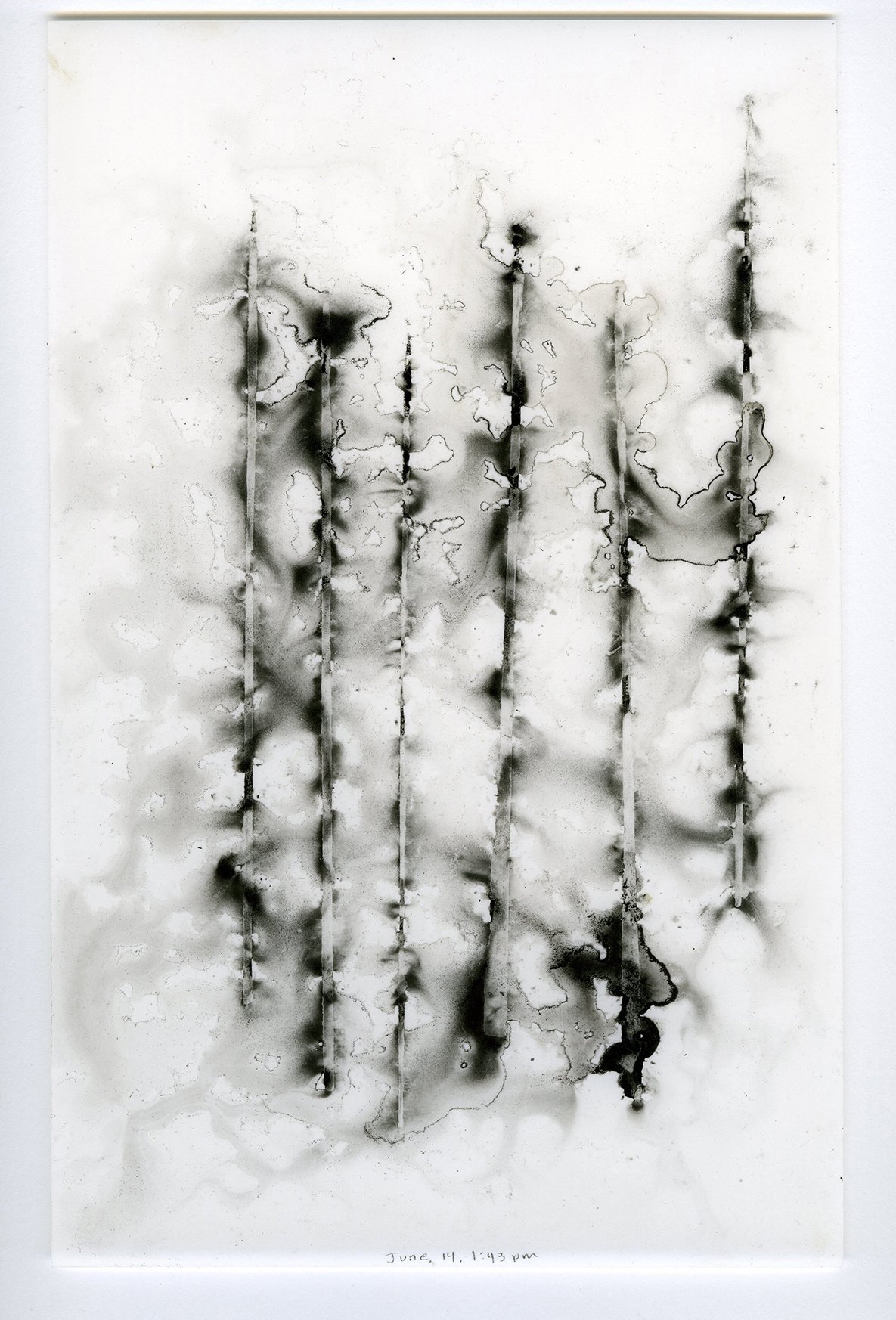

MH: In your series Wind Drawings, you lay charcoal on a sheet of Arches paper, and then what? You place it in the wind? Please describe how this works.

SW: In this case I’m stamping the paper with charcoal powder and another medium, otherwise it all blows off the paper. And again, I decide when it’s done. On these drawings I record the direction and speed of the wind. This notation is part of the narrative, like a mark.

MH: When we look at the finished piece, what do you want the viewer to see? What do you see? Is it a nature-based drawing, or a sort of cross-section of time?

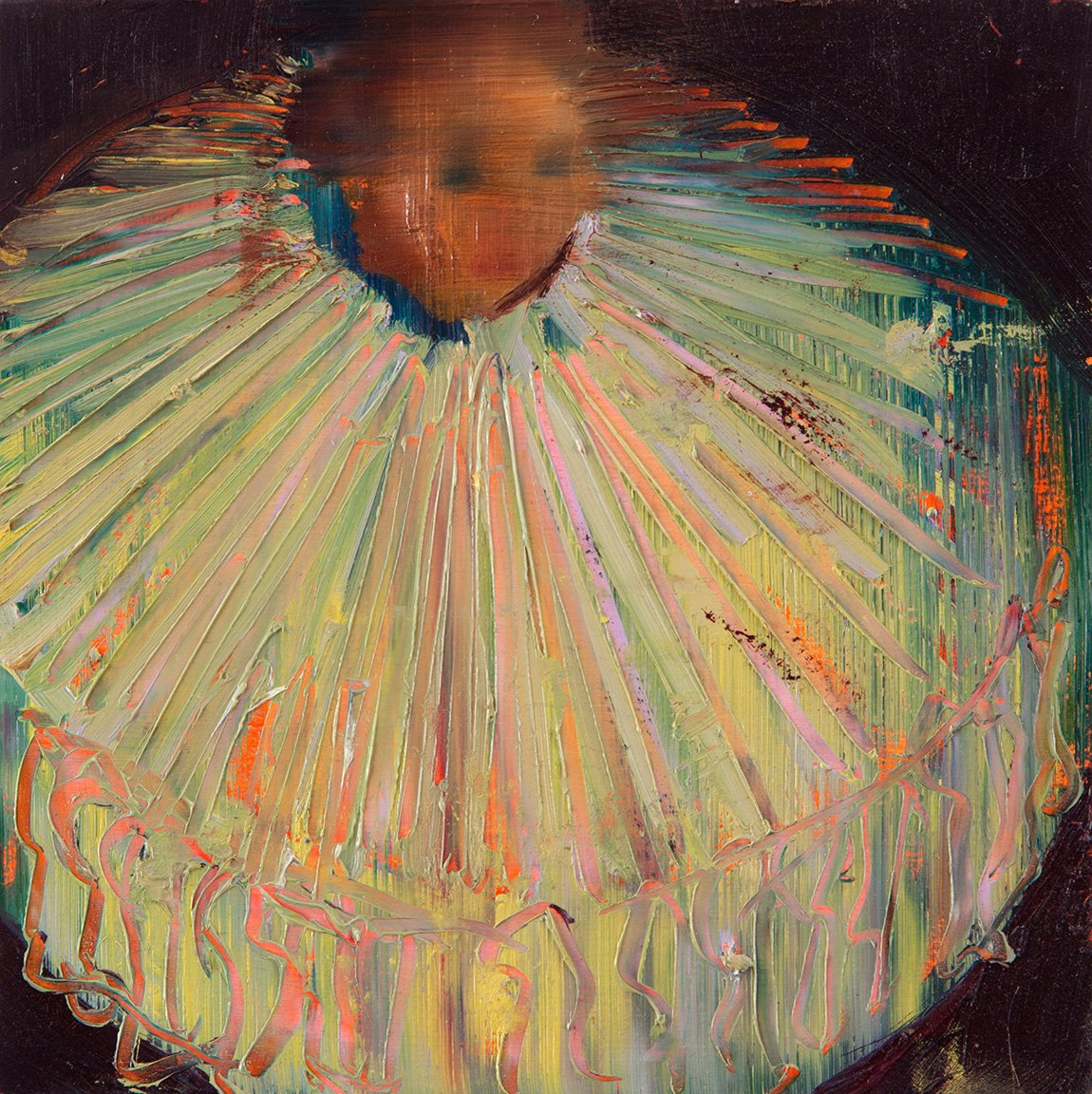

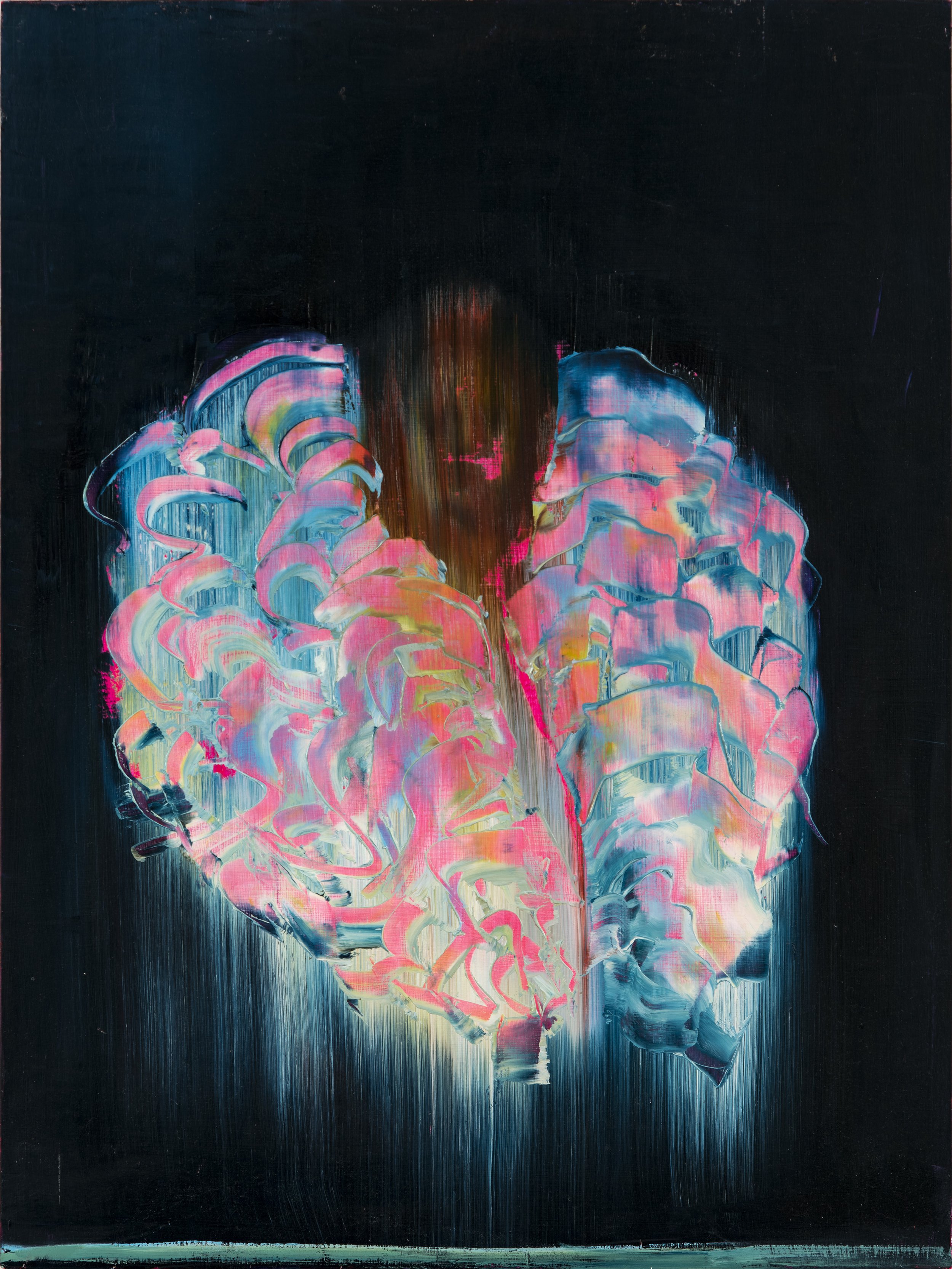

SW: The main thing I’m hoping for people to see is the energy of that element, like the energy of the sun or rain or a wave. I do a lot of experimentation to make this happen so that you first perceive the energy of that thing, and then maybe you see associations to landscape. Like with the wind drawings, some people see them as trees, and with the waves some people see them as the sea. But first I want them to see the energy of those elements, because the true energy is astounding, and that’s what I’m trying to get at. It’s a quieter energy.

MH: It’s interesting that your work isn’t about the charcoal or the ink or pigments, it’s about the energy of the element, but you need something to show where the rain or wave has been.

SW: Yes, the studio is basically an experimentation lab, where I’m trying to find the right materials to convey a certain energy. What properties do charcoal have that will convey the energy of the wind, or gouache to convey the waves?

MH: I’m curious if you engage with the process as an artist purely aesthetically, or do you also feel like a scientist or researcher, with little regard for the visual “product”?

SW: I’d say it’s somewhere in the middle. I’m reading the scientists, the botanists, all the books that excite me about these topics. Right now I’m reading a book about the cultural aspects of rain, but in the experimentation process there are all these aesthetic concerns that I take into consideration. I want the work to be appealing; I want people to feel pleasure when they look at it. It’s more poetry than science.

MH: You don’t have any control, really, over the visual product, except in the very beginning.

SW: Well, yes—I do make decisions about the color of the gouache. That’s an aesthetic decision. The pigments separate as they dry, which is also an aesthetic decision. But as soon as I put it out, I no longer have any control, and that’s what I’m looking for. I don’t want any control. I want there to be an invitation, I want to let go, I want to see what this thing can do, and then I decide when it’s done. So it really is about time.

MH: There are a lot of things that you could do to make your work more “flashy”, less quiet. Like manipulate it into mandalas with Photoshop to give it more visual appeal, that kind of thing. But you don’t. Is that a deliberate choice, not to make it flashy?

SW: I don’t want my work to be flashy, so I don’t need to manipulate it. I like how quiet it is, and I like that the connection it makes to other people is a quiet connection. One year I took some of my thread drawings down to one of the art fairs in Miami, and all the art was loud and screaming, and there were my little, quiet thread drawings (haha). I sold a few pieces, but I realized that my work is not art fair work at all.

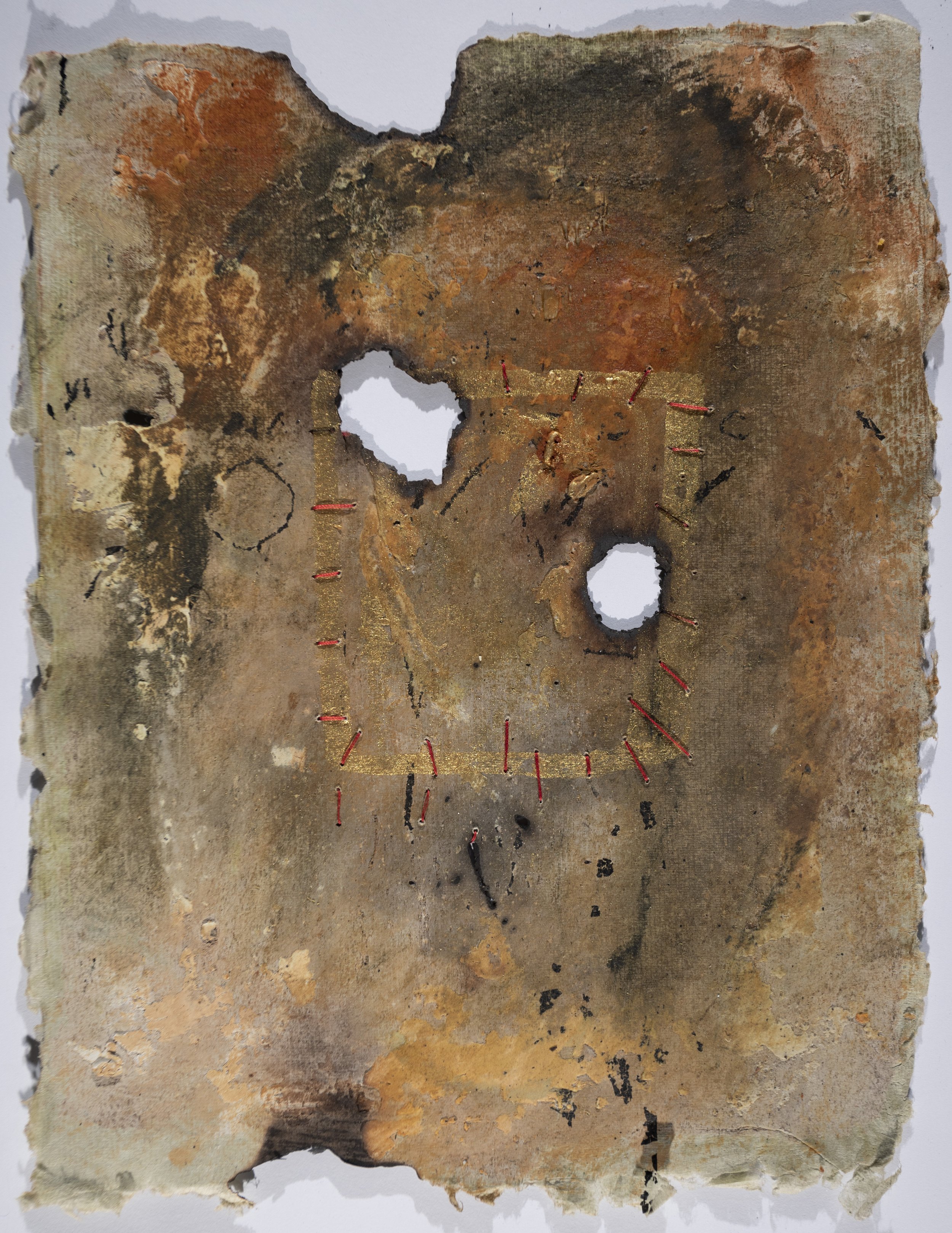

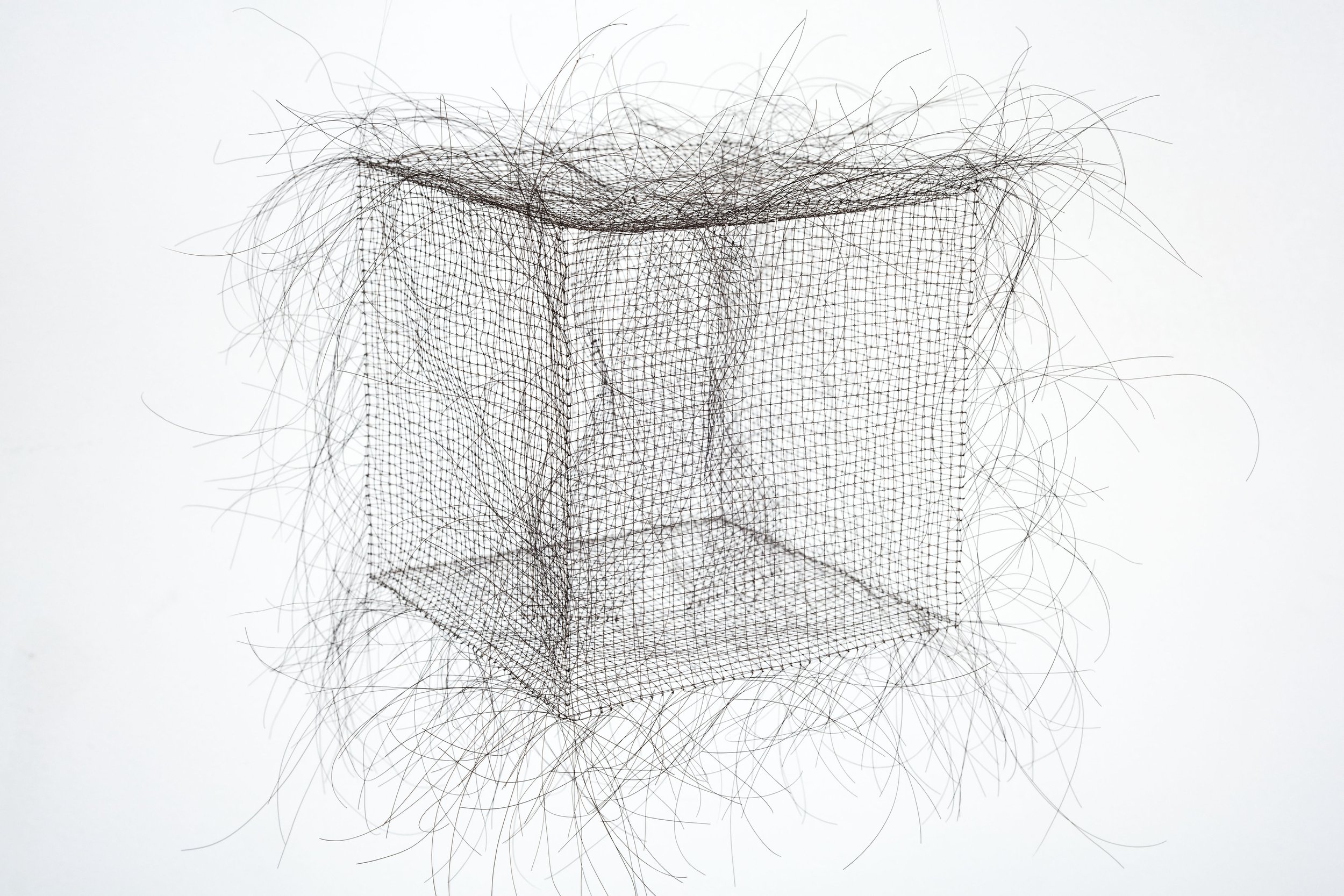

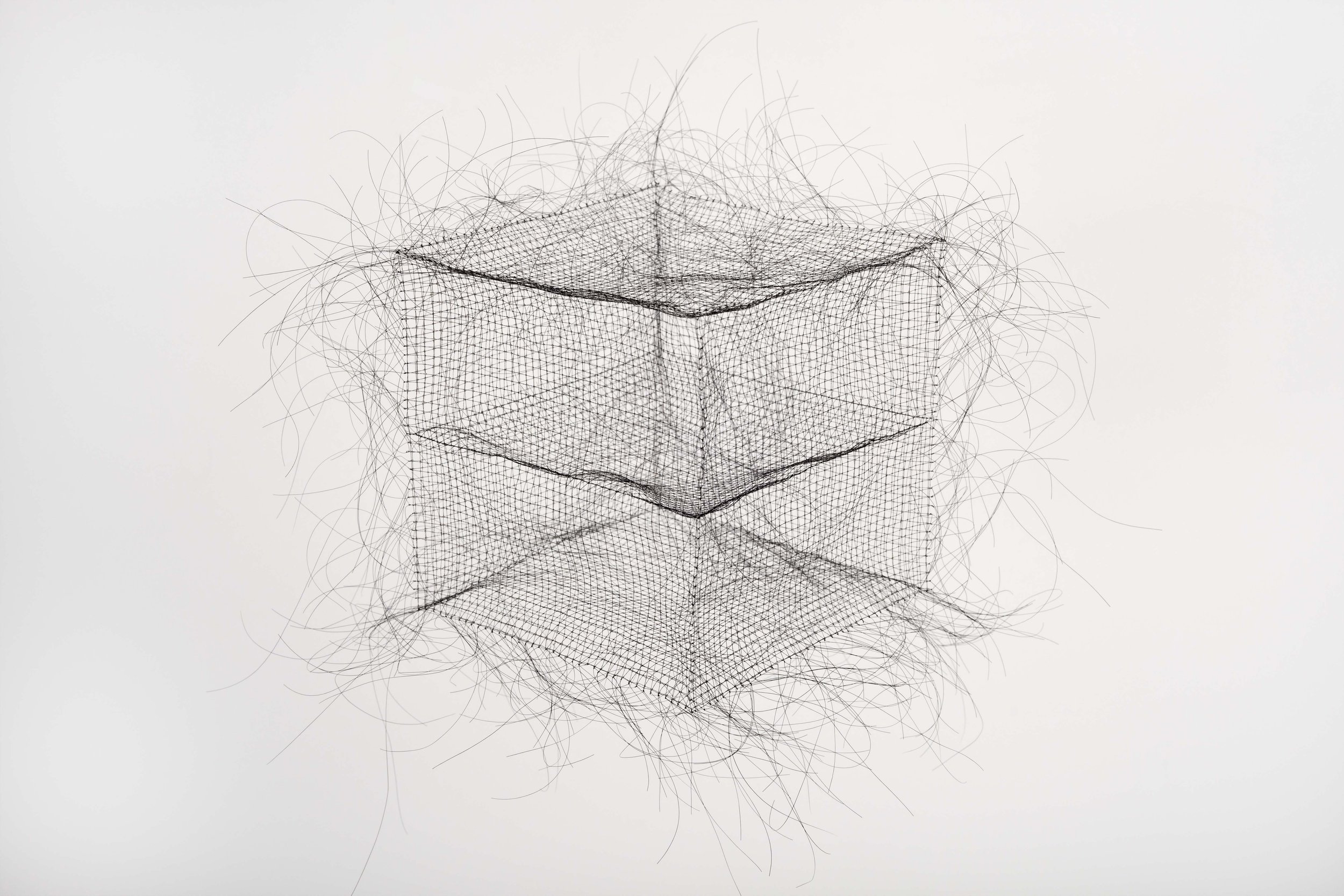

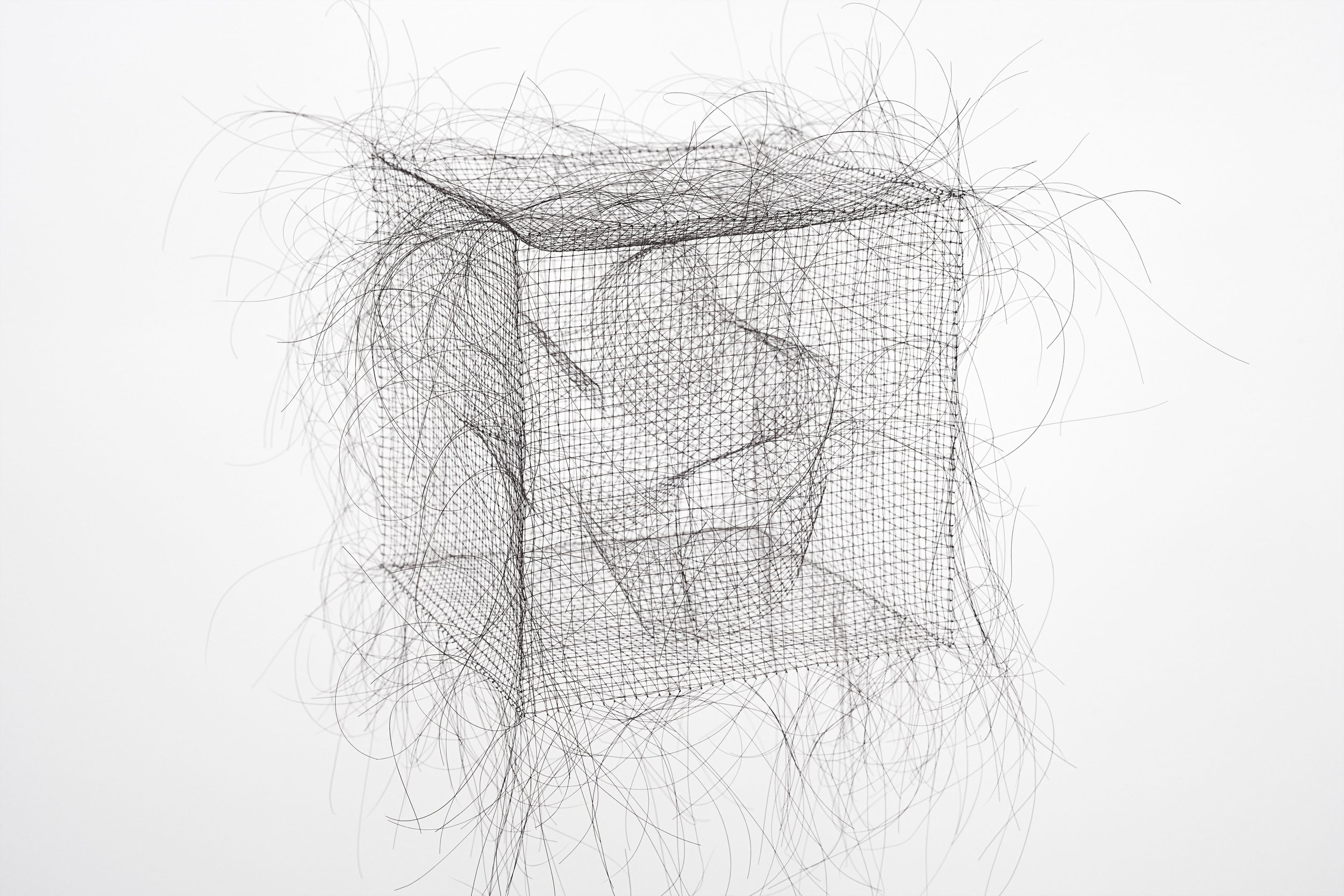

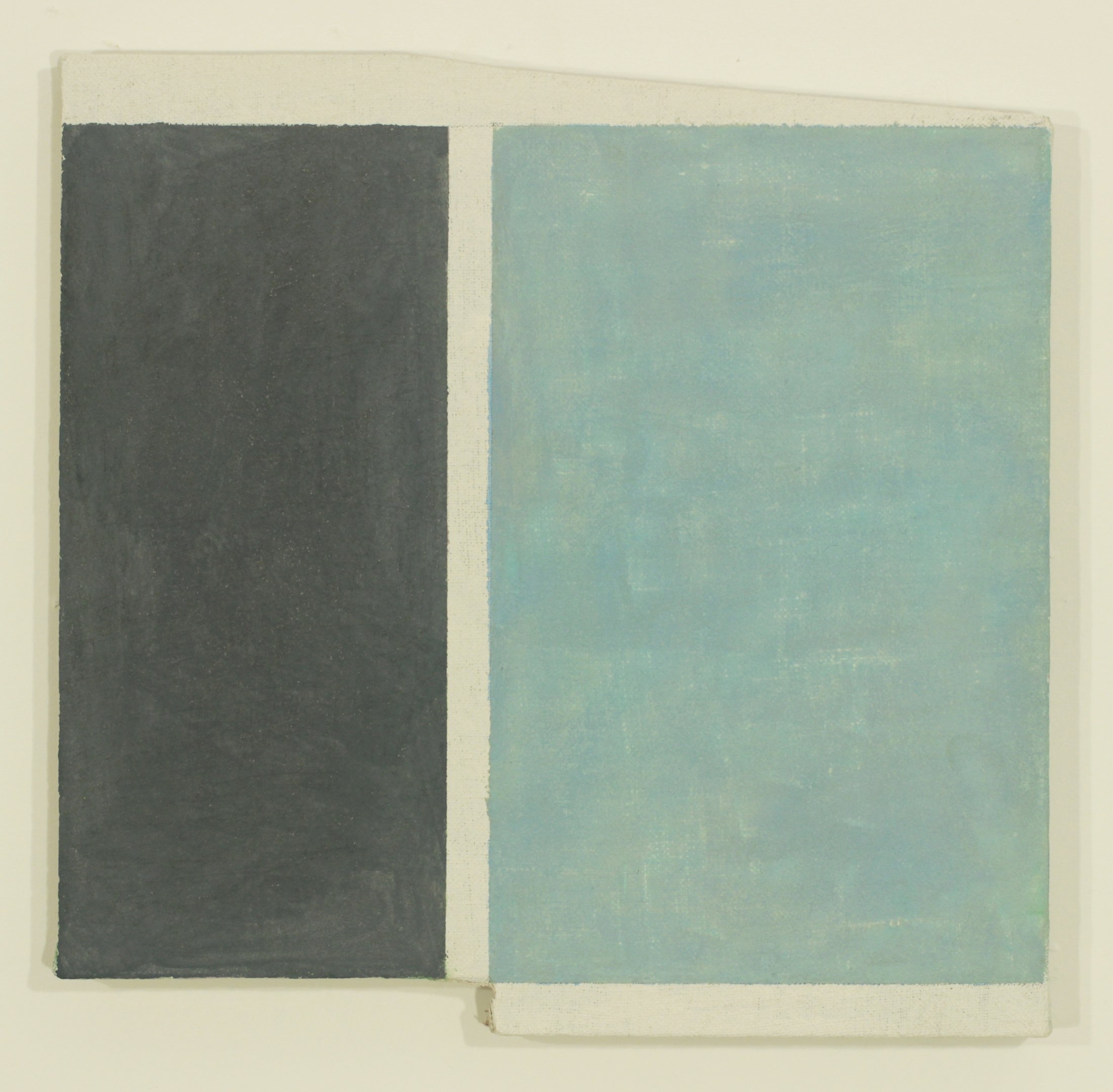

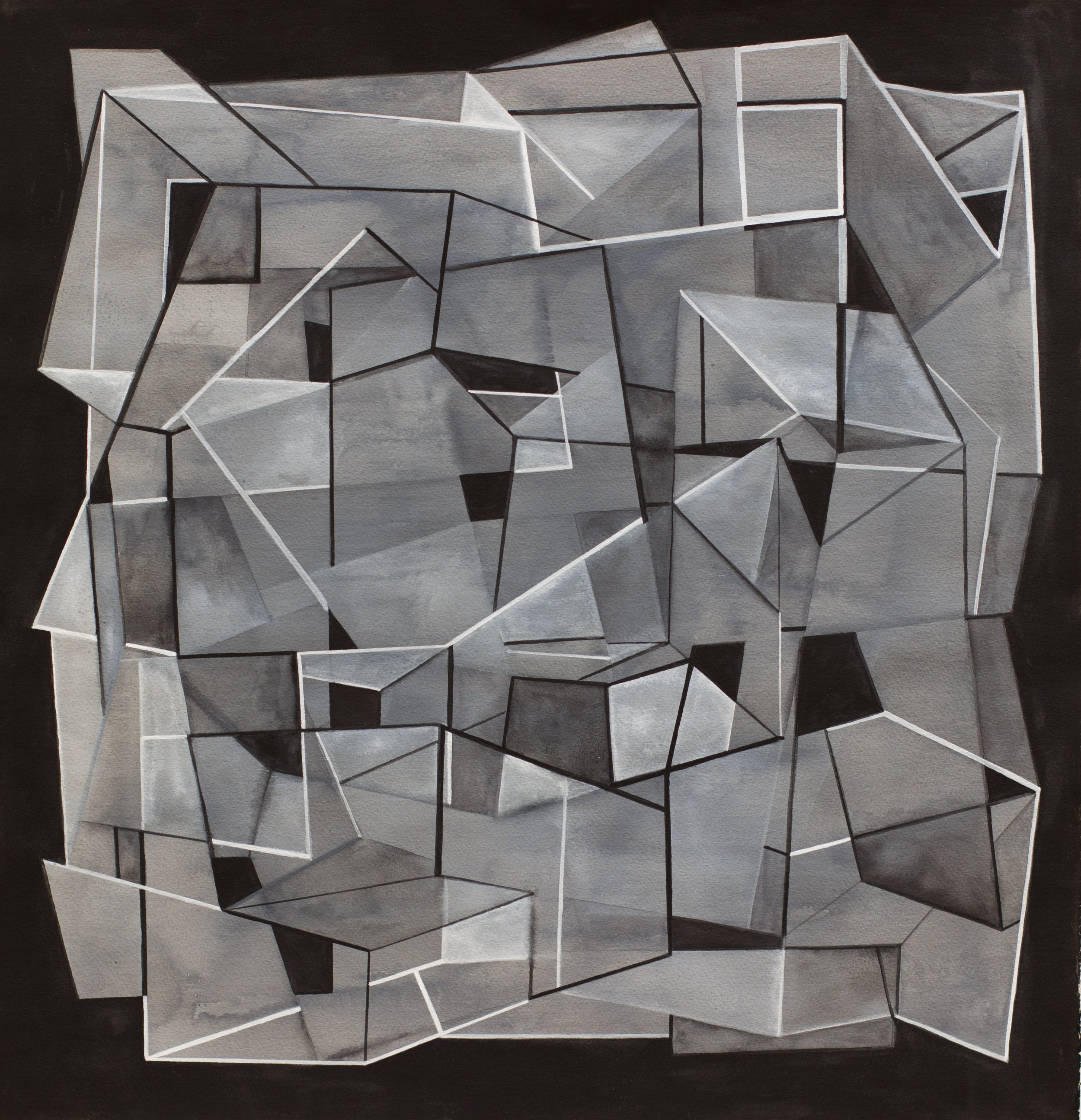

MH: In another series, Time Story, you continue to work with the elements to reveal time, but now time becomes geological. There are topographies and ancient time-keeping methods such as sundials and wood patterns that narrate the life of a tree. How does moving into three dimensions expand your investigation of time?

SW: I see the three-dimensional work as something that exists in space and changes from moment to moment. The sun casts a shadow, and seeing how it reacts with my sculpture is interesting to me. There are these cycles in nature that we don’t really notice because we don’t slow down, but I get to see it in my sculpture. So the three-dimensional work is active, not inert. But then if I photograph it, that becomes a fixed moment.

MH: Your participation in the process is essential but minimally invasive. You gather the materials, set them up, then step away from the process. It brings up some interesting questions regarding the will of the artist as well as your self-identification as an artist. Have you wrestled with your role and identity in your practice?

SW: Someone once asked me if I was the artist or if rain was the artist. I don’t struggle with it because some of the art that I’m really drawn to is process-based and experiential, and I like fitting into that camp. There are so many artists who have inspired me, and who have done this kind of work, like Robert Irwin who creates a condition of natural light, theater scrim, and space that slowly changes for the viewer moment by moment. I also like the work of Meghann Riepenhoff, who creates large scale cyanotypes in frozen water, and works where the wind and rain inscribe ice crystals onto the paper.

MH: Your work is very conceptual and cerebral which makes it interesting, but it’s also beautiful. The finished piece has a quiet elegance to it.

SW: Yes, thank you! It starts in the mind like an outline and ends with a quiet trace of a sensory, physical experience.

MH: Whether you’re a scientist or lab technician or artist, if you didn’t set this whole thing up, it wouldn’t happen. So your intention is essential, but your participation is minimal.

SW: I see my participation and the elements’ participation as an equal collaboration. The elements are making the marks, but I spend a lot of time experimenting with materials before I get to the point of setting up the drawing. Like when I first tried to do the wind drawings, I couldn’t find the right energy, and eventually I figured out that the speed of the wind had to be between 14 and 20 mph. If it was less it just sat on the paper, if it was more it would just blow off. With the thread drawings, I discovered that it was only between January and March when the sun is really low in the sky that it works; any other time I can’t get the desired effects. So even though it all looks very simple, it’s complex and takes a lot of trial and error.

MH: What is the difference between an artist and a technician? I’m thinking not only of the set-up of your drawings, but also of the painter who has amazing technical skills, but whose work is little more than a display of virtuosity, a portrait that’s life-like but sterile. Is there a meaningful distinction between being an artist and being a savvy technician?

SW: I think the artist is always going to look for the poetry. I don’t think the technician would be able to let go of control. Being a good technician means that you get it just right, you tighten the bolts, you’re drawing the lines perfectly and precisely. My work is not about that. So the letting go is the poetry and the art. It’s where the work goes when I let go.

MH: Well, your work is most definitely poetic, almost by definition. I mean, I don’t know why anyone would go to all the trouble of setting up these visual experiments, if she wasn’t an artist or poet.

SW: Hahaha! So true. Why would they? Charcoal powder is dirty, the wind is a pain, so why would anyone bother?

MH: I’m curious if your studio practice is also a spiritual practice of some sort. It seems to lend itself to that, not only in its focus on time as material, but also on you, the artist, as a temporal agent. If you do your job right, you simply disappear. How do you feel about that?

SW: So spot on. I don’t consider my studio in Newburgh to be my only studio. The studio is also the mountain, my walk, and the whole thing is absolutely a spiritual practice. It’s about slowing down, seeing the constant return of the breath. The idea of the return of the seasons is comforting to me, and the idea of returning to something in terms of material interests me. I’m just figuring out ways to let go and get quiet enough to be open to some magical thing out there.

MH: I’m quoting you here: “The work is complete when the viewer experiences the absence of the material that makes it.” You could substitute the word “artist” for “material”. Is it your ultimate goal to paint yourself out of the picture, as it were?

SW: I wouldn’t say that’s my goal, but I think that’s happening with the work. The elements take the main stage, and that’s okay. I wrote that the material is absent, but in reality I think it’s still there. The rain, the wind, it’s all still there. But I don’t think it’s my goal to paint myself out of the picture, no.

MH: What is your goal, then? Do you have one?

SW: The last time I checked in about this, I wanted to convey that there’s something out there that’s so ubiquitous that maybe we don’t notice it. So if I can convey an awareness of this beauty, which is in the energy of the rain, the wind, and the waves, then that’s the goal. I don’t think that’s painting myself out of the picture, but I’m okay with it if it is.

MH: What’s the best part about being an artist?

SW: I feel so lucky that I have a form for all these crazy things that I’m curious about, and when I go off on these curious tangents, I love where I end up. And then I get to share that excitement with colleagues and friends, which gives me community and connection. It’s such an incredible journey and I love it.

www.susanwalshstudio.com

The artist’s work is featured in Fresh 2023 at Klompching Gallery in Dumbo through Oct. 21, 2023.