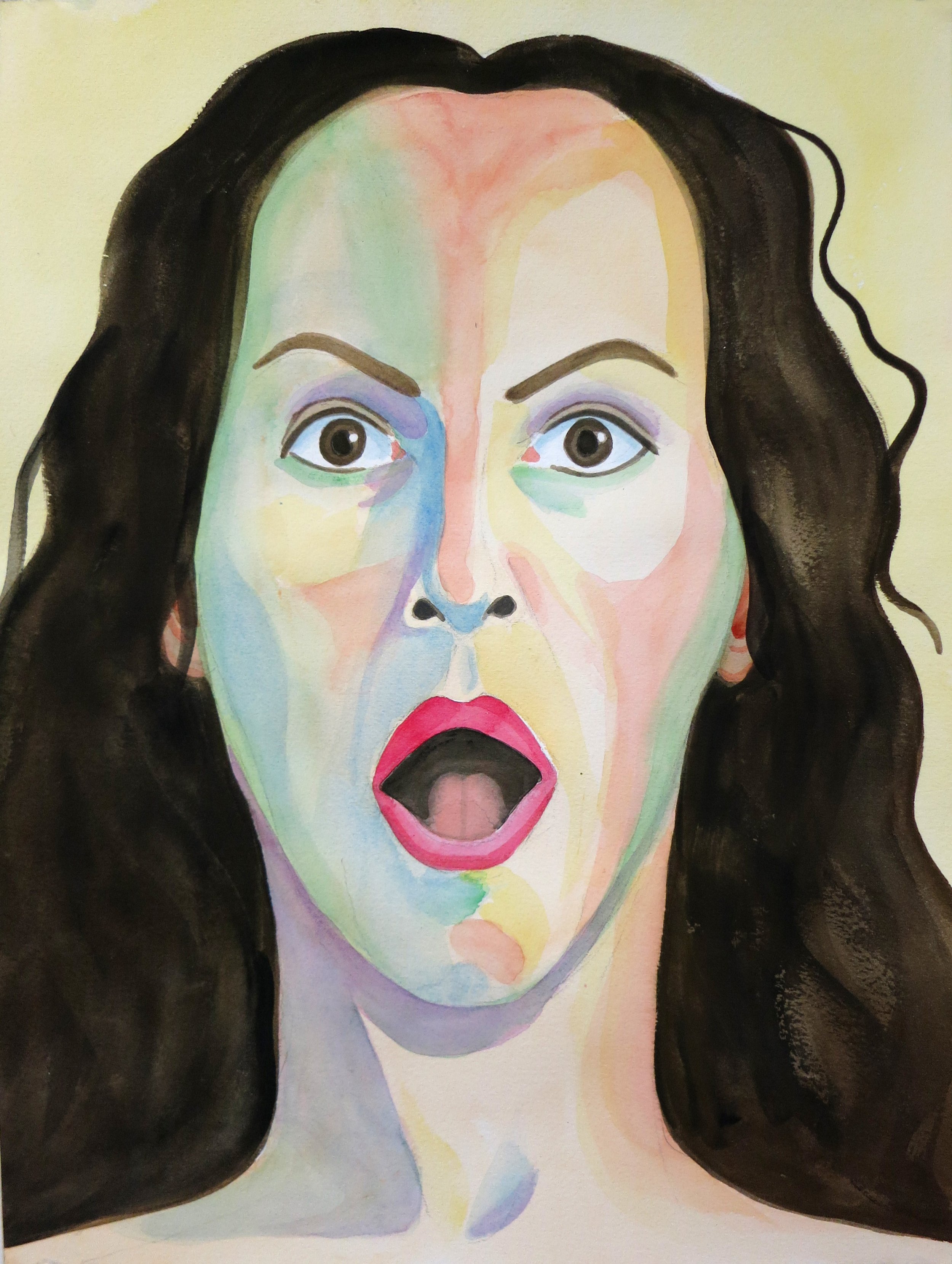

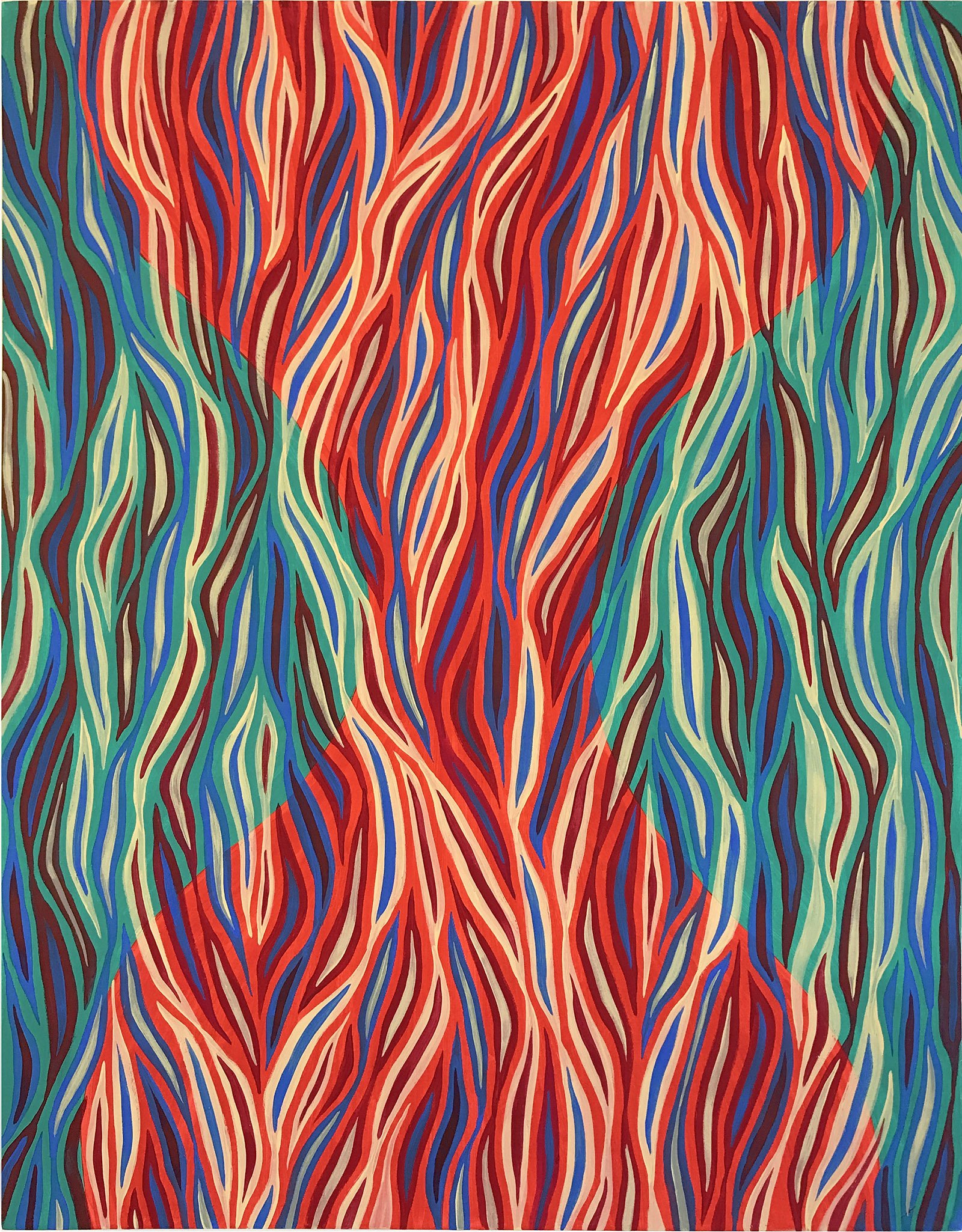

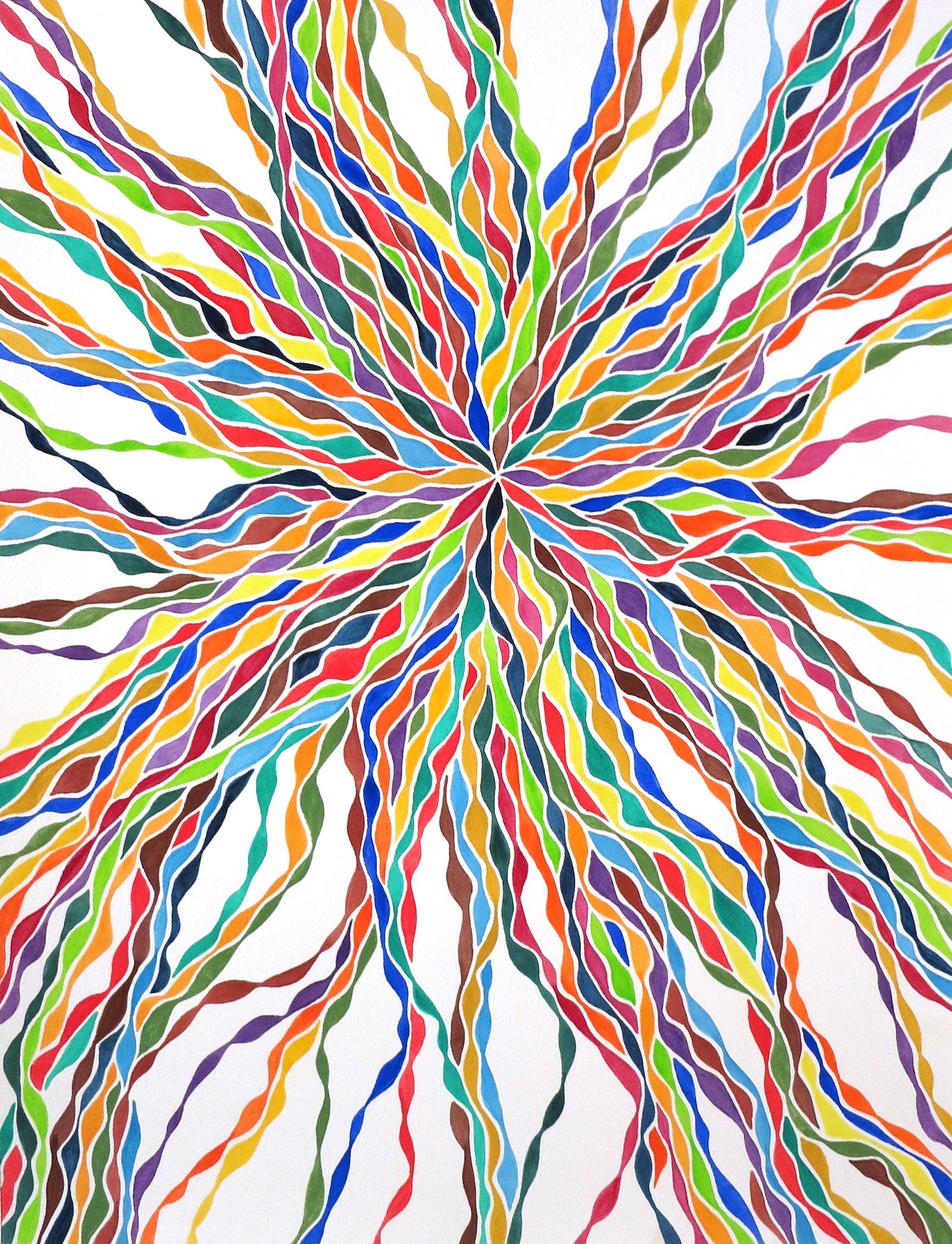

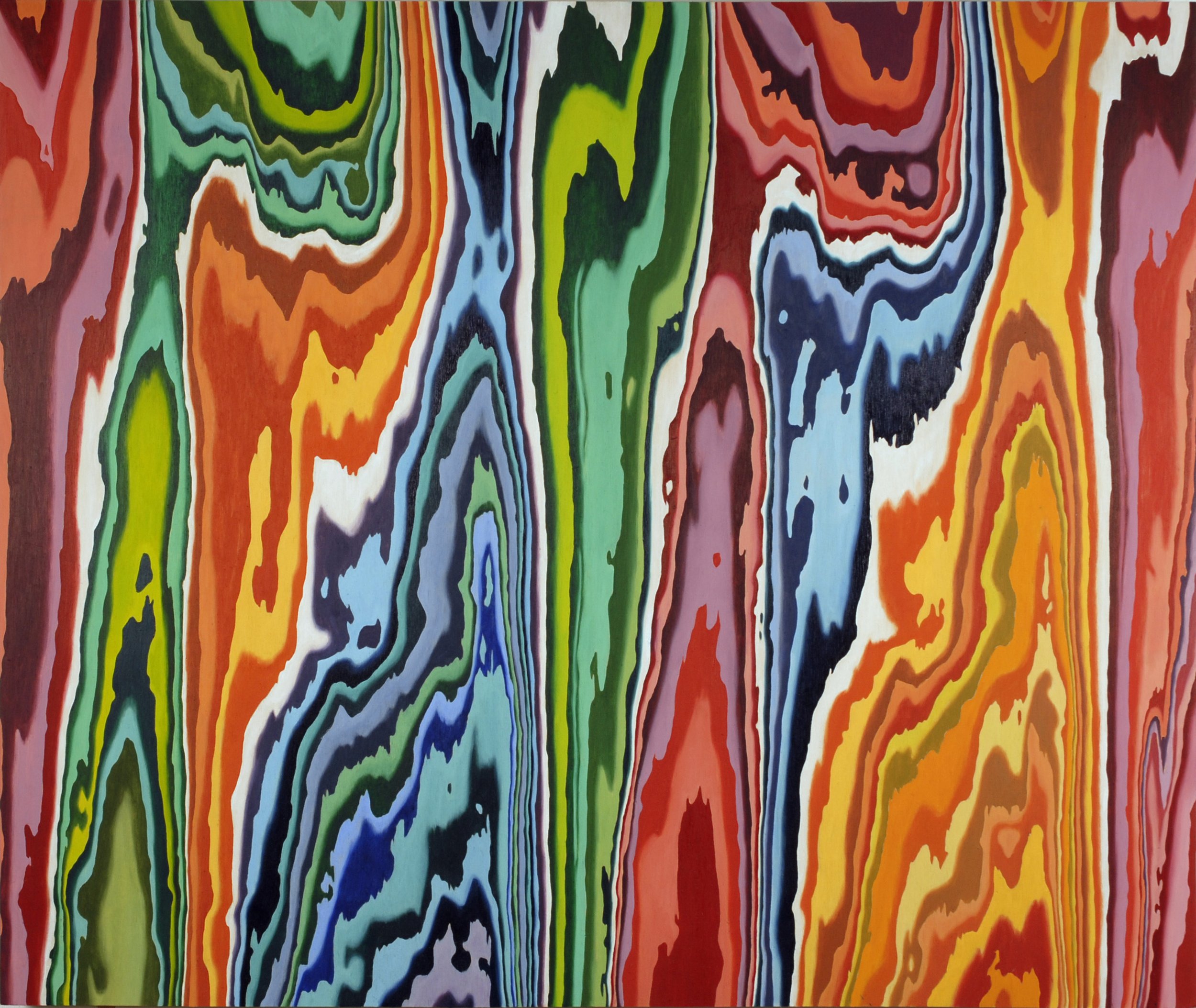

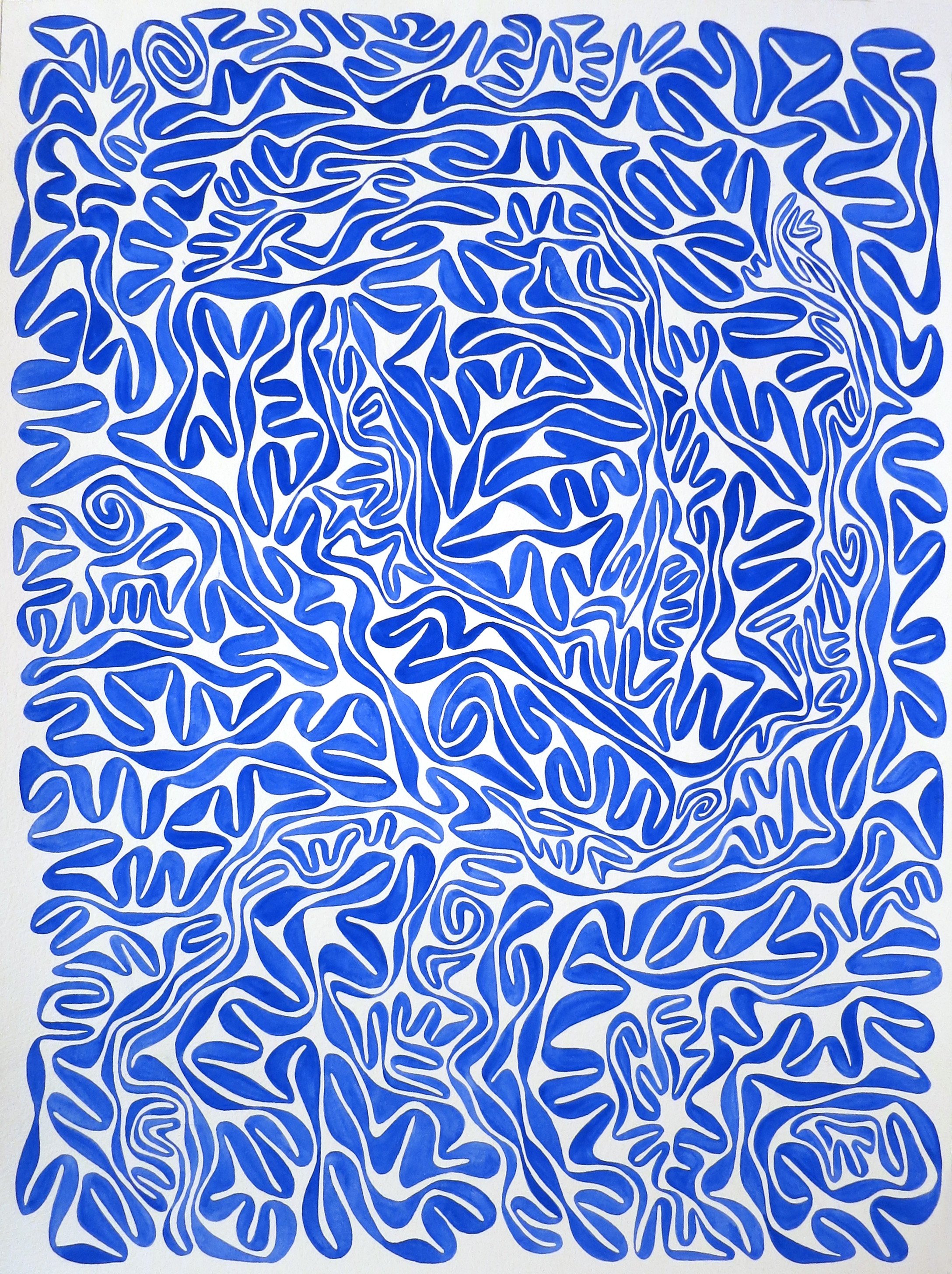

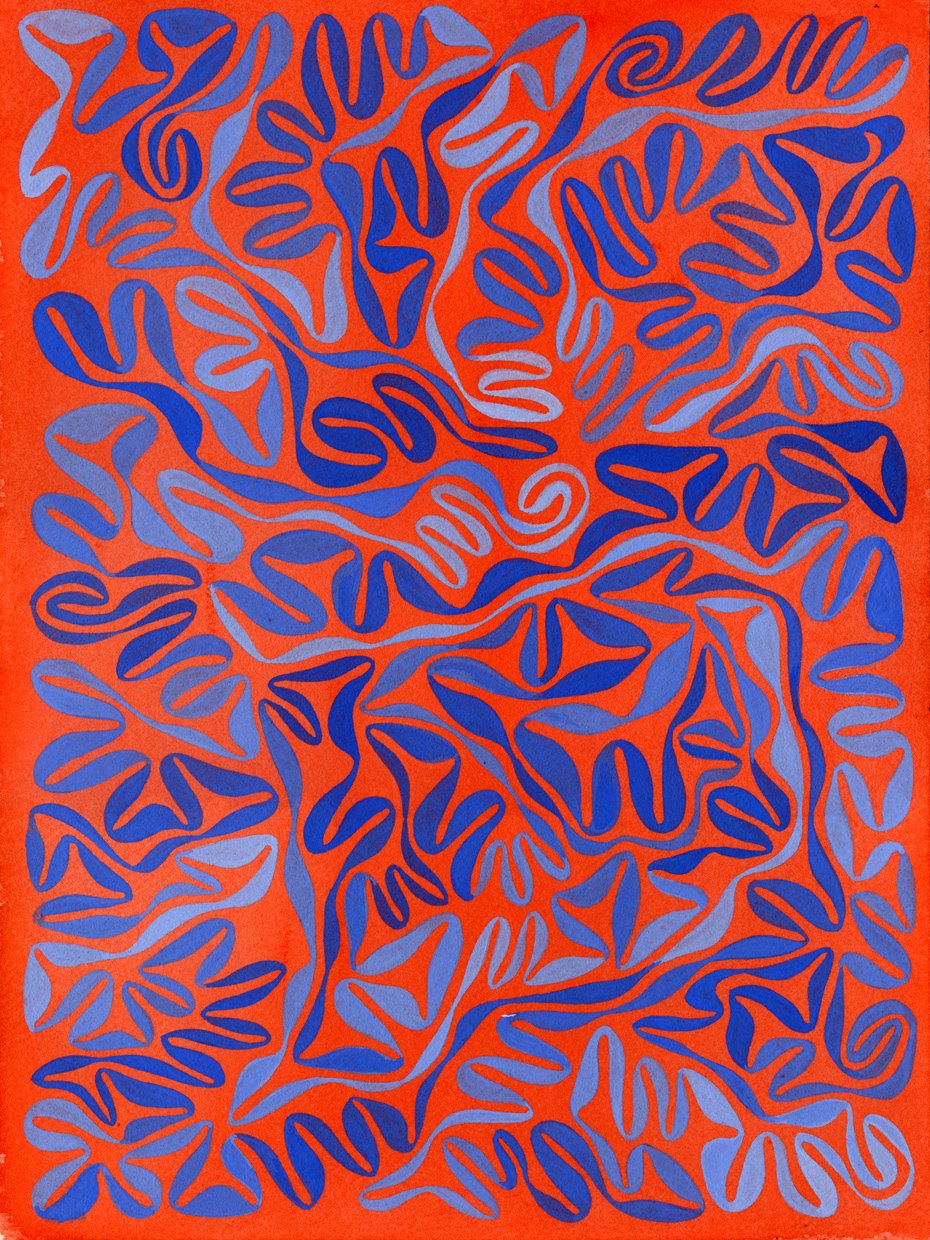

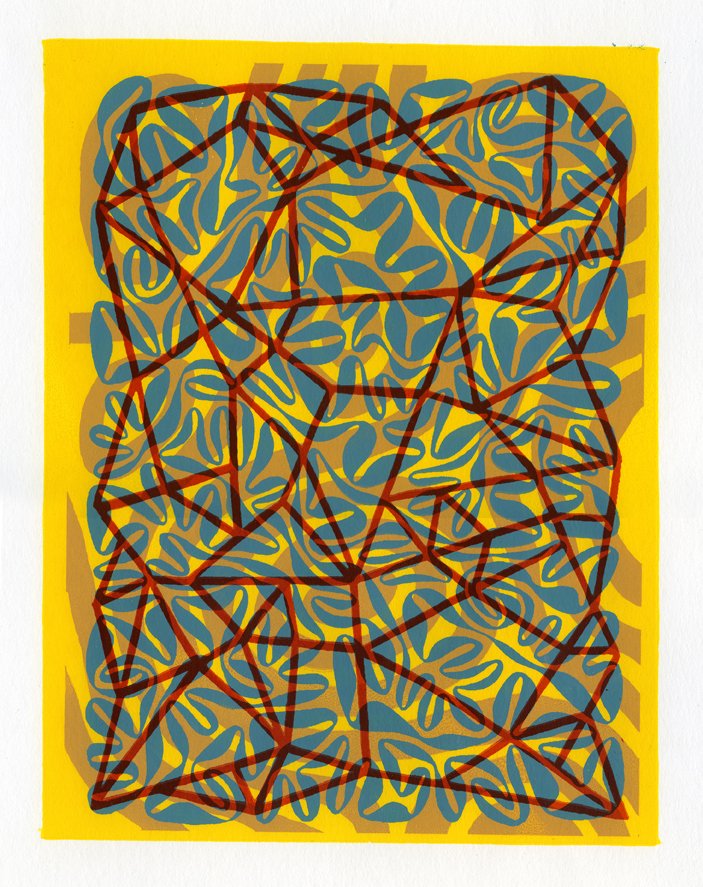

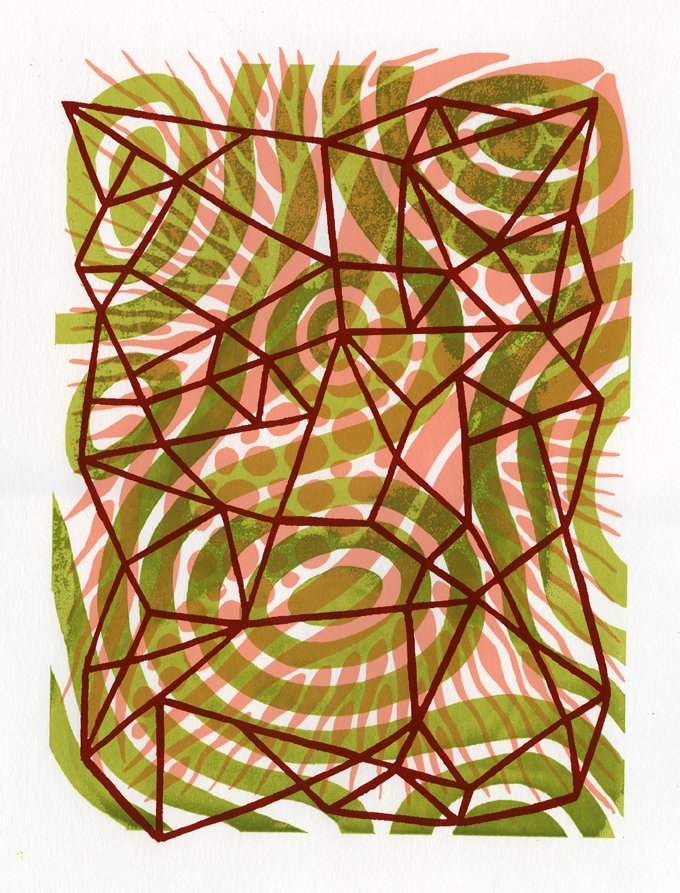

Patricia Fabricant is a Brooklyn-based artist who works in a variety of styles, from painterly portraits to woven icons to pure abstraction. Her enduring interest in portraiture led her to paint herself in unconventional poses, with grins and grimaces that are at once humorous and disturbing. The unflattering aspect of her self-portraits makes sense in the context of the series, which was a direct response to the 2016 presidential election. Fabricant painted her horror, shock, and rage, then wove them together to express more than one emotion at a time. She also wove the self-portraits with paintings of mandalas, creating icons with radiating halos that recall Byzantine Madonnas. It’s astonishing how many self-portraits Fabricant painted to create her weavings, and one admires the tenacity of a middle-aged woman to scrutinize herself in the mirror for three solid years. Indeed, when she reached her saturation point, Fabricant returned to the abstract patterns that she was painting prior to 2016. This series has a raw energy that is similar to the woven self-portraits: whimsical, textured, and vibrating with layers of saturated color. Also like the self-portraits, the patterns seem to point beyond themselves, not to a failed presidency, but to a meditative state induced by the intense concentration of the artist. Like radiant strands of DNA, the interweaving colors multiply and assert their own order within the chaos of the painting. In her ongoing exploration of pattern and decoration, Fabricant has created a life form that is a metaphor for something deeply complex and nonverbal.

MH: Over the years your work has gone back and forth between figuration and abstraction. How do you regard subject matter in your work, and how important is it to you?

PF: As a student I was primarily a figurative artist, and my senior thesis show was all portraits. I didn’t call them portraits, though; I called them paintings of people, because I wasn’t interested in creating a likeness. Later, when my work became predominantly abstract, I stayed connected to the figure by going to life drawing sessions. A big pivot in my work happened in 2016, following the presidential election. I’d been painting decorative abstract work up until that point, but in the face of what we were going through as a country, the work felt trivial. It didn’t seem like a path forward at that critical moment, and I was experiencing so many emotions – horror, shock, fury, sadness – that I started to look deeply into myself, and what came out of it were expressive self-portraits. As far as subject matter, it’s not critical to me. With the abstract work I avoid a subject altogether, even though there’s a human impulse to see one in the work.

MH: The self-portraits are funny, sometimes serious, always vulnerable. I love that some of them are so unflattering. What led you to paint yourself in this light?

PF: After the 2016 elections, I wanted to confront my anger head on, so I made a distorted facial expression and painted it while looking in the mirror. It felt like I was making my own emojis. It was never about trying to make myself look good; I wanted to try to get at something more real.

MH: Jean-Paul Sartre wrote that if you look at yourself in a mirror for too long, you'll see a monkey. Was it difficult to spend so much time looking in the mirror? What came up for you?

PF: Yes, it was, and one of the things that came up was how much my face has changed, and what the middle-aged face looks like. It’s the same as when you look at a word too long. I’m a graphic designer and sometimes I’ll look at a word for so long that it suddenly looks wrong. This is what happened with my face, and why I eventually went back to abstraction.

MH: So you painted hundreds of these self-portraits, and at some point you started to cut them into strips and weave them. It’s interesting how the series evolved, and I wondered if you would talk about the inspiration behind weaving them.

PF: It was partly a result of the raw anger I was feeling about our new president – that feeling of wanting to break things, but I didn’t want to ruin the things in my apartment, so I started breaking my art by cutting it into strips. The weaving came together when I was trying to express more than one emotion at the same time, so I’d weave funny and angry together. It went through a lot of iterations: I painted portraits of other people and wove them into my self-portrait, I did a series where only half the face was woven, I did a series that I call “Icons”, where I painted mandalas and then wove my self-portrait into them, creating a radiating effect, and I painted flowers and wove myself together with them.

MH: Some of the woven self-portraits distort your face into a fleshy blob. One can read a lot into this: annihilation of the ego, loss of selfhood, or perhaps you were painting the monkey. How did it feel to paint yourself as no-self? Was it liberating in some way?

PF: I didn’t actually paint myself as no-self; the no-self came when I wove them together. So even though there wasn’t a conscious decision to obliterate the self, that was the result. Someone pointed out to me that in the woven self-portraits, only half of each painting is visible; the other half is behind the other portrait. So in effect there is a shadow self-portrait hidden beneath what you see. I love that idea.

MH: You came to an end with this series and moved into the abstract patterns that you’re still painting. Why did you depart from the self-portraits, and how did you arrive at the current series?

PF: After three years of self-portraits, I couldn’t look at myself anymore. I was doing these small, fluorescent abstractions on the side, and I realized that I was returning to something that felt familiar and inspiring. I was ready to go back into that body of work.

MH: What is it about this style of working that appeals to you? Is it primarily process-oriented, or do they have a conceptual underpinning?

PF: It’s primarily process oriented. I make some formal decisions when I start so that I have a sense of where I’m going with it, and then I lose myself in the process. So they’re more formal than conceptual in my approach and inspiration.

MH: What do you mean when you say formal?

PF: They’re more about form, composition, color, line, relationships, layering, and that’s where they connect to the self-portraits. Even though I’m not literally weaving, what I’m creating has the effect of something that’s woven. I’m interested in the ambiguity inherent in layering. I don't necessarily want it to be clear which shapes are on top and which recede into the background.

MH: In reference to these paintings, you write that the work may be the by-product of your need to create your own internal order to cope with the chaos outside your head. (Terribly misquoted – sorry!) Does painting abstract patterns feel appropriate for our current political climate? More broadly, does pure abstraction serve as a kind of convenient speechlessness? A sensuous veil that covers up the grotesque?

PF: That’s an interesting perspective. The self-portraits were a reaction to the chaos and horror of our time, but maybe decoration is as well. Maybe this is a way of putting up a veil between me and the world.

MH: In a sense you could say that all of art is a veil between our existence and some imagined world. Should we even expect art to be more than that?

PF: There have been points in history where art has made a difference. Like that portrait of George Floyd that was everywhere and resonated so much. And then there’s Goya, Picasso’s Guernica; there have always been artists who confront political issues directly and who make a difference. Some are didactic, some require so much explanation that the work almost doesn’t matter because you have to read a whole essay to understand it. It’s more that we need art to sustain ourselves as a species, rather than whether art moves the needle in any way.

MH: In your current series of abstractions, there’s an energy that comes from the lines that feels like it has its own intelligence. They appear to be complex organisms that create their own order within chaos. How do you regard the lines and shapes?

PF: One of the things that’s important to me is that you can see the imperfections and the hand in the painting. The undulating lines create a texture that can look like hair or the surface of water or drapery. I feel like it’s successful when it has that surface texture. Sometimes when I’m working on a painting, I’ll see something happening and I’ll sort of coax it out and let it take over. The way this process works is that when they’re done, they’re done. I don’t go back into them. The hard part for me is restraint; I tend to fill them in completely, so I’m trying to hold back and leave space. It’s not my nature; I have a little horror vacui, or maybe its OCD.

MH: You refer to the Pattern and Decoration movement as an influence in your work. Would you briefly explain what the P&D movement was, and how it has inspired you?

PF: The P&D movement emerged in the early ‘70s, primarily women led, and unapologetically decorative. It was a feminist-based movement, and in some sense, a reaction to Minimalism, which was more austere and masculine. They used techniques in art-making traditionally associated with women’s work: sewing, weaving, quilting, and decoration. So I saw this show at Los Angeles MOCA, “With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art”, and it was very exciting to me, because there were some artists that I know who are still actively working: Arlene Slavin, Joyce Kosloff, Dee Shapiro. Seeing the show helped me put some context into my own work with pattern and design. It validated my work in a lot of ways and made me feel that I was connecting to something bigger.

MH: Pattern implies repetition, and unbroken repetition often gives rise to a meditative state. The sheer accumulation of shapes can create a state of suspension, or even of awe. Was this ever discussed as part of the P&D movement? Namely, was there the potential for the pattern to create a state of transcendence?

PF: That’s an interesting question. I haven’t read anything that indicates that, but I know that it’s something that I feel keenly when I’m working. It’s hard to imagine that it didn’t happen for them as well.

MH: Is there the potential for the patterns that you make to create a state of transcendence for you? That out-of-body experience where you’re super focused and everything else slips away?

PF: They absolutely do. I completely lose myself in the making, and my aim is to create that effect for the viewer as well.

MH: Have you ever experienced awe in the face of accumulation? I’m thinking of Tara Donovan, who uses everyday objects like drinking straws – zillions of them – to create massive sculptures, or Islamic designs that are based on a single, interlocking shape. Also, the work of Wolfgang Laib, who painstakingly collects jars of pollen for his installations. Are you drawn to this type of work?

PF: 100%. I often feel awed by art, but accumulation has a big impact on me, and can spark that feeling of awe.

MH: Do you think that patterning and repetition beget a certain intelligence, an internal order that gently takes over the painting? The artist can either fight it or go with the flow and see what arises. Have you experienced this, and if so, are you comfortable giving up the driver’s seat?

PF: I have an ongoing push and pull with the work. I’m open to letting it drive me a bit, and sometimes I’ll gently nudge it back. Other times I’ll make a mistake, and then decide to go with it rather than try to correct my mistake. That’s really ceding control for me. But there’s a lot of control in what I’m doing for sure. It’s not loose, it’s not gestural.

MH: How do you hope people will react to your pattern paintings? What’s the optimum response?

PF: Awe would be the optimum response, and for that I need to push to a larger scale so they encompass an entire field of vision. At their current size, they’re more like objects, which I like, but I’m interested in what scale would do. I’m more interested in a visceral response than an intellectual one.

MH: You also do a fair amount of curating. How does that figure into your creative practice?

PF: I love curating, and that’s more about my intellectual side. The curations that I’ve done are aesthetically driven, but I love putting things together in a logical way. I think this derives from my work as a designer; I design a lot of art books and it uses another part of my brain that I also use when I curate.

MH: What’s the best part about being an artist?

PF: I love the community. I know some artists who are real introverts and hate having to go out, but I love communicating with artists and having artists in my life. I also like the fact that I never have to retire, that I can keep doing this for the rest of my life.