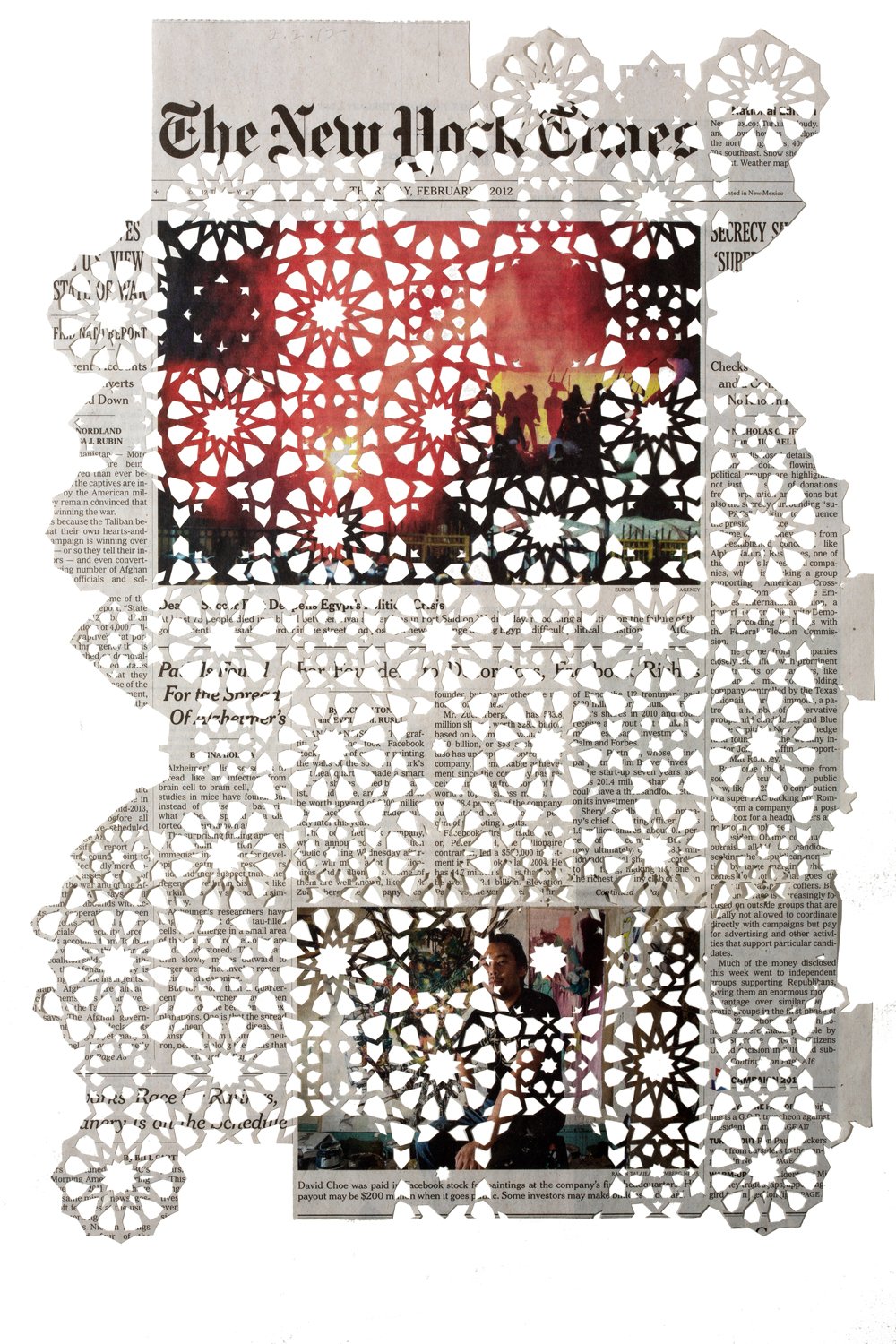

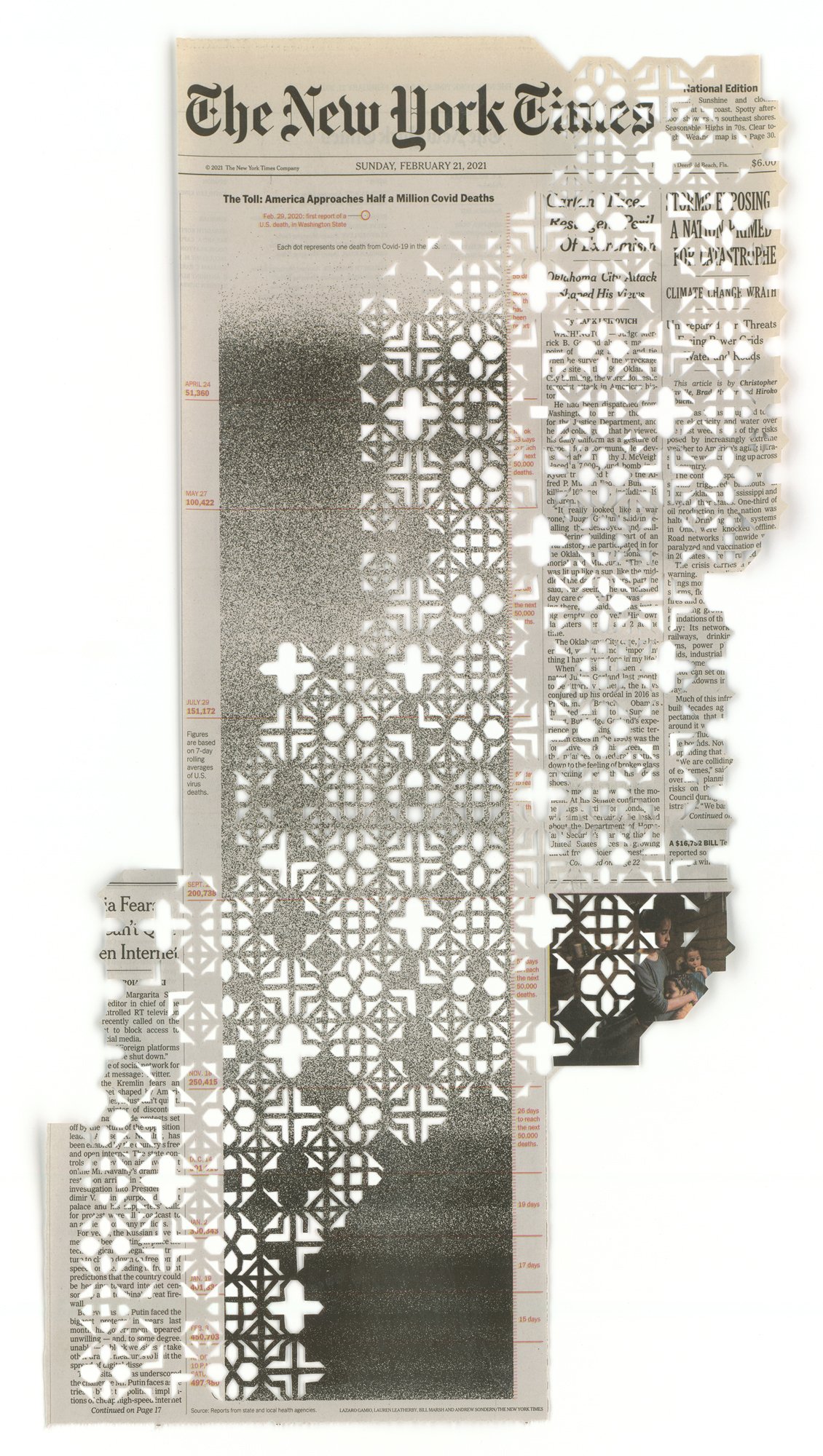

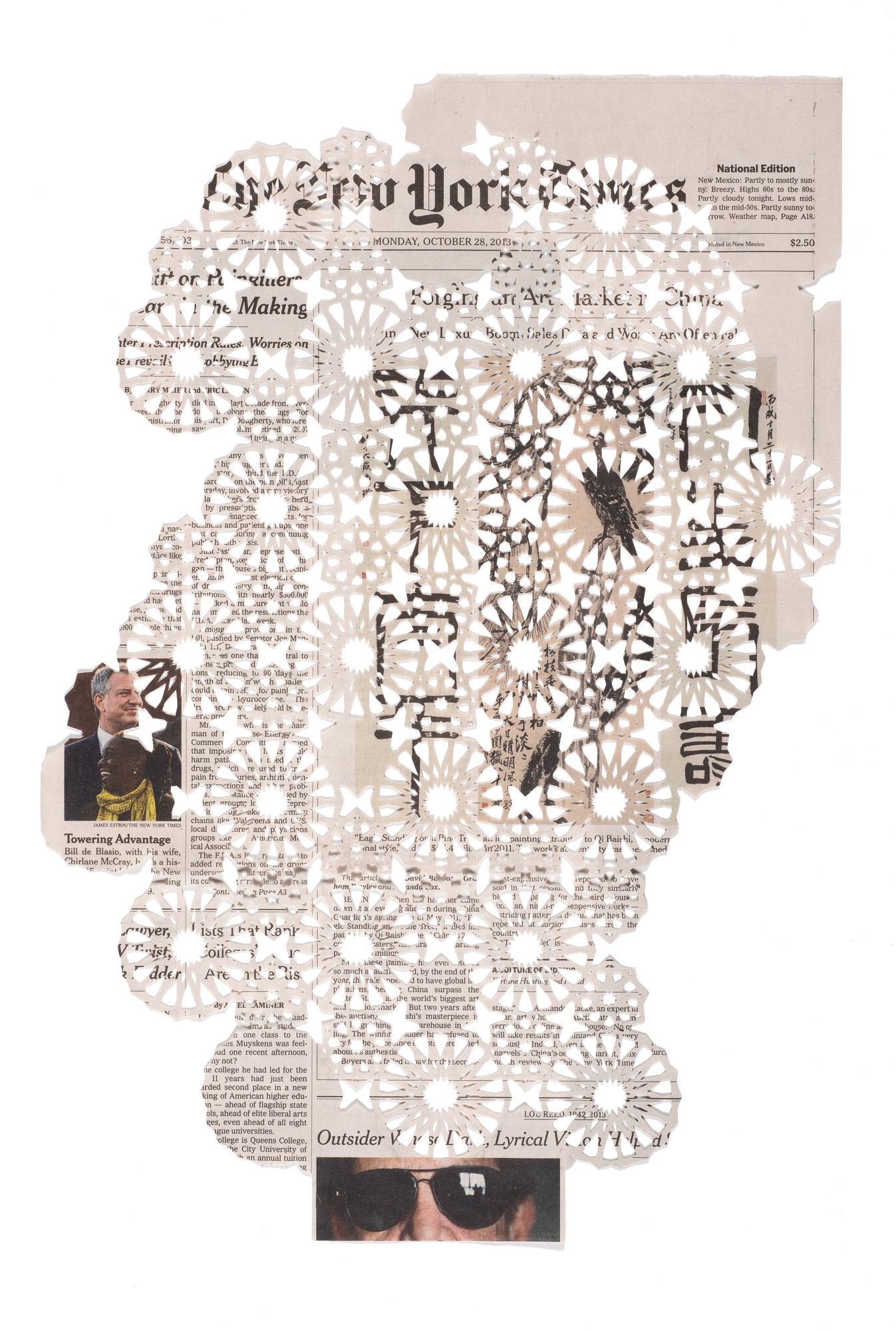

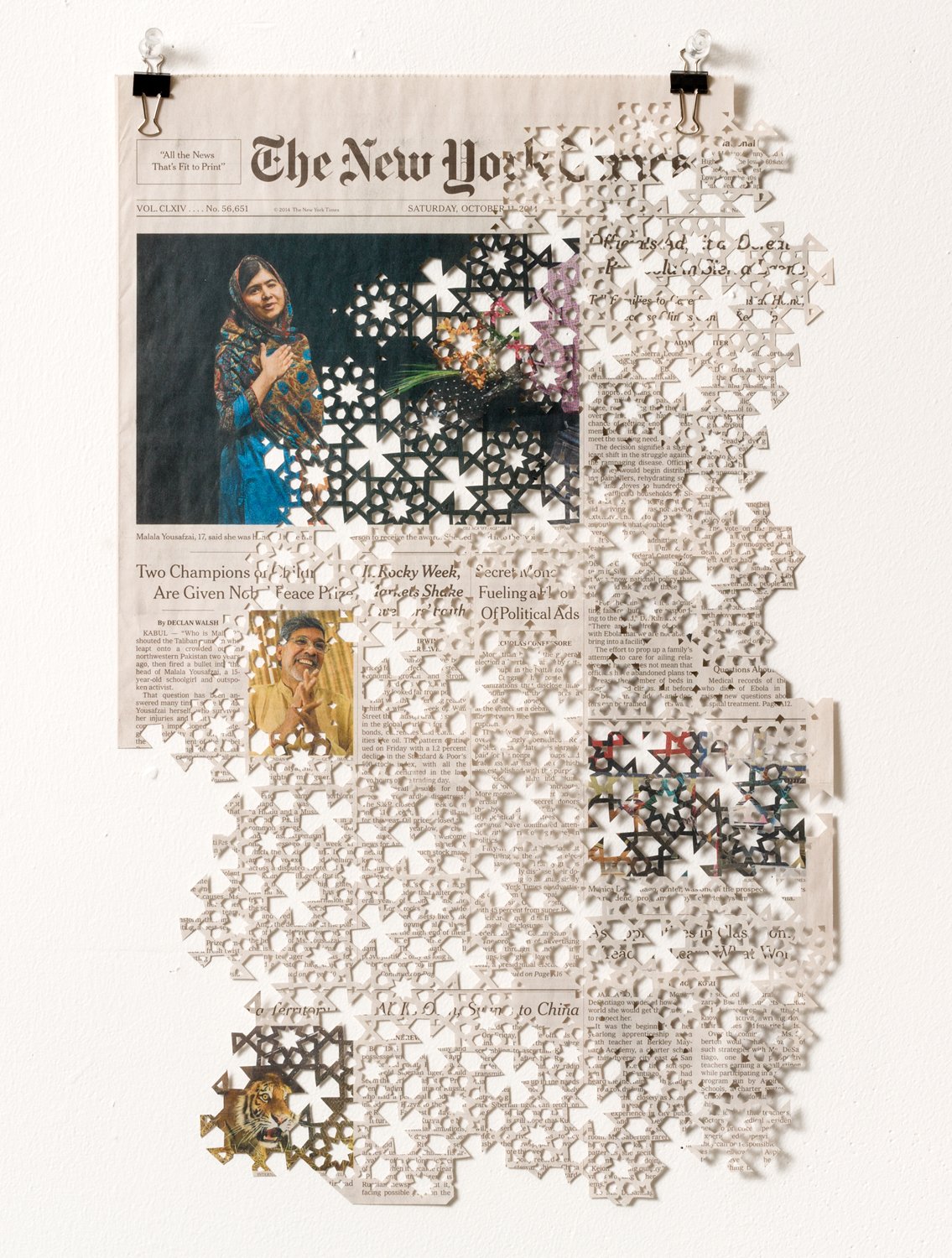

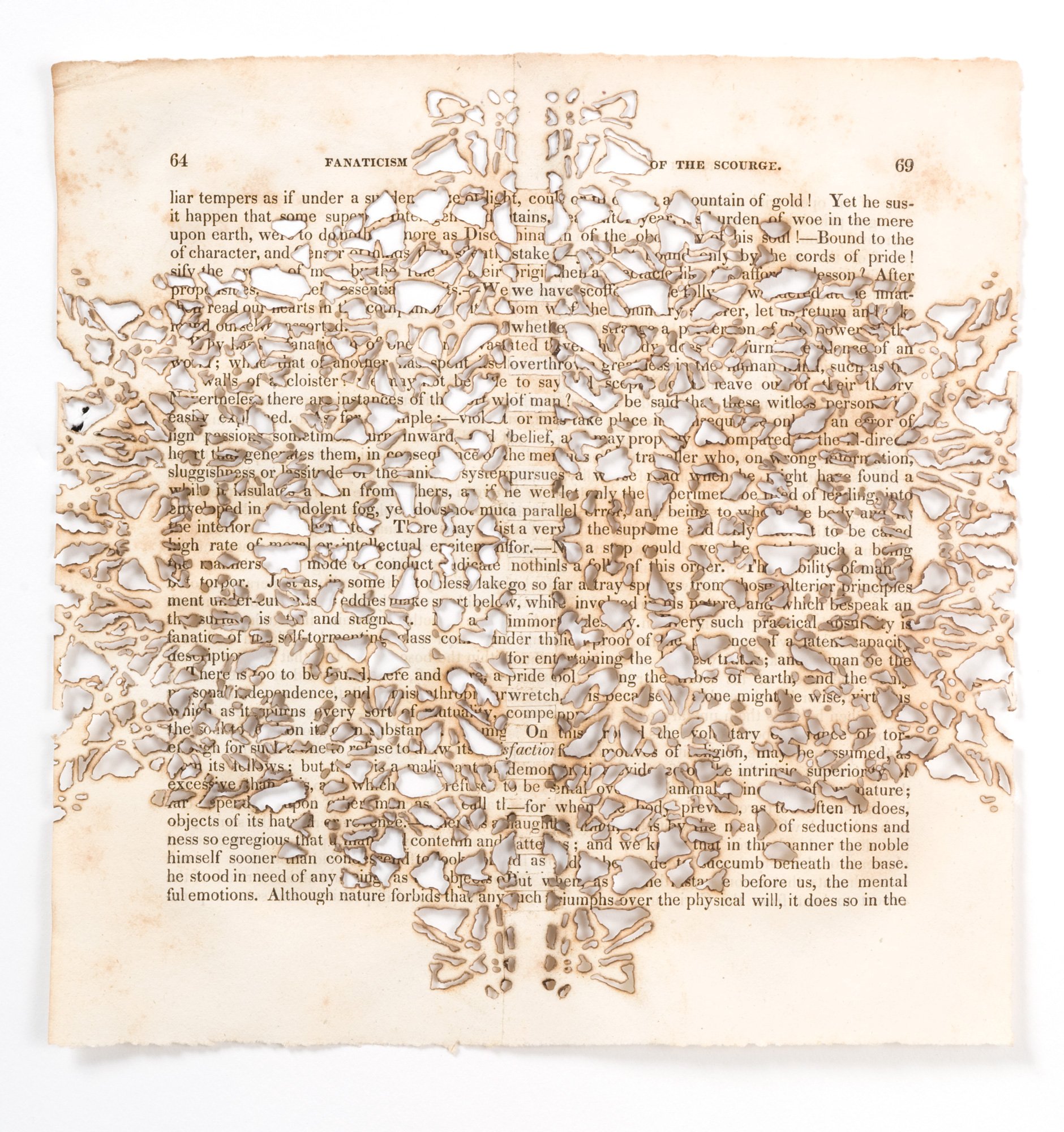

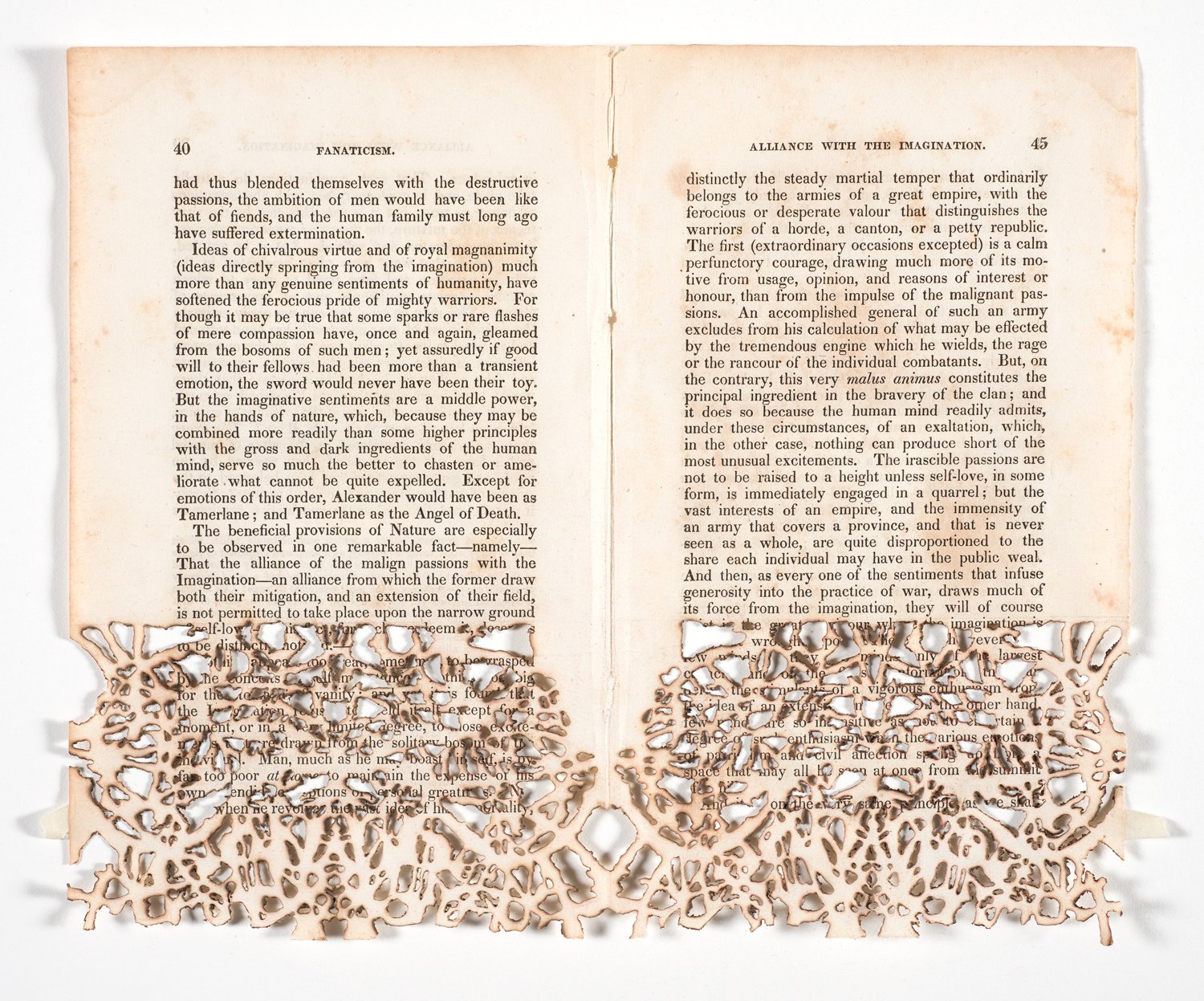

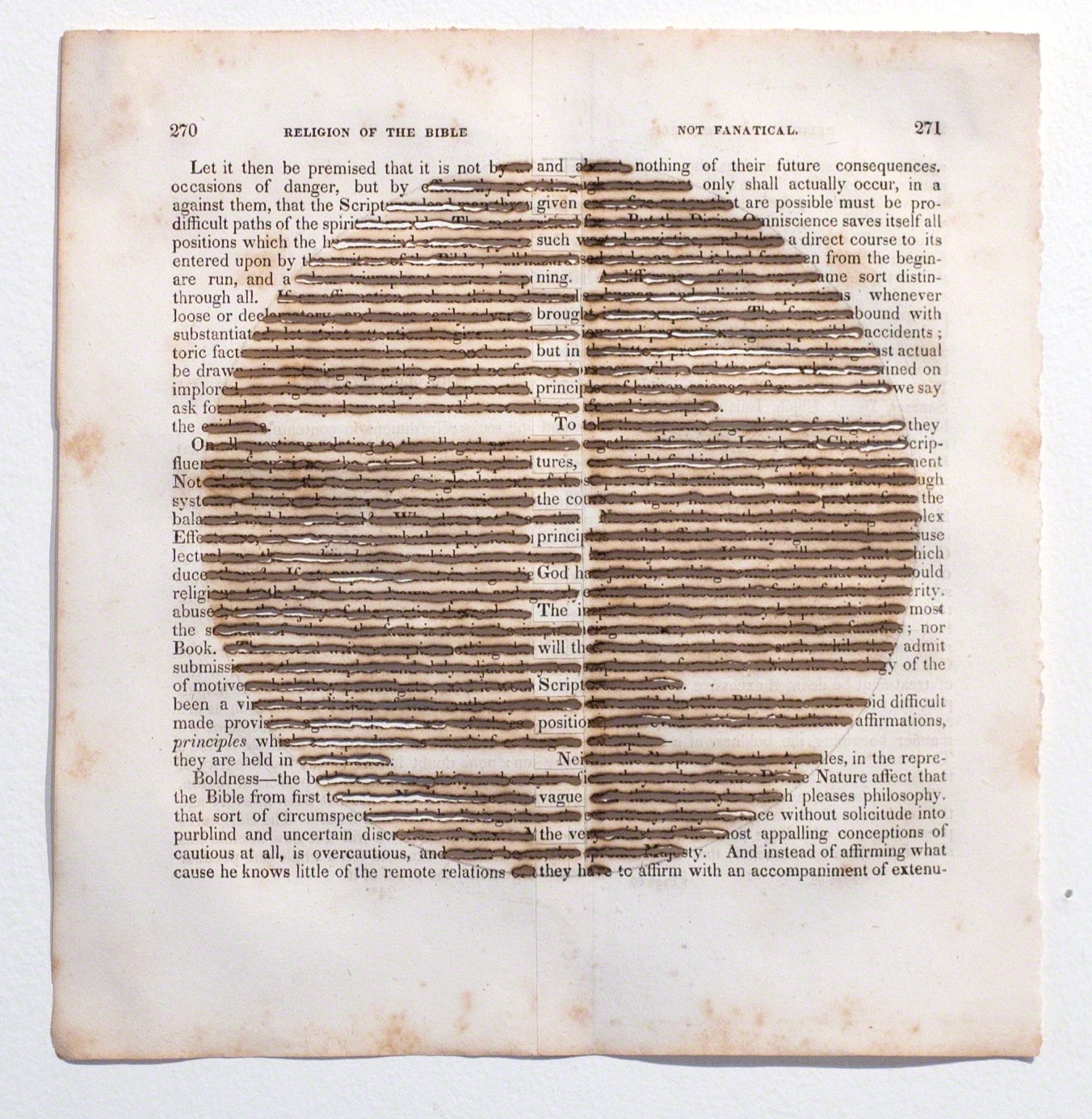

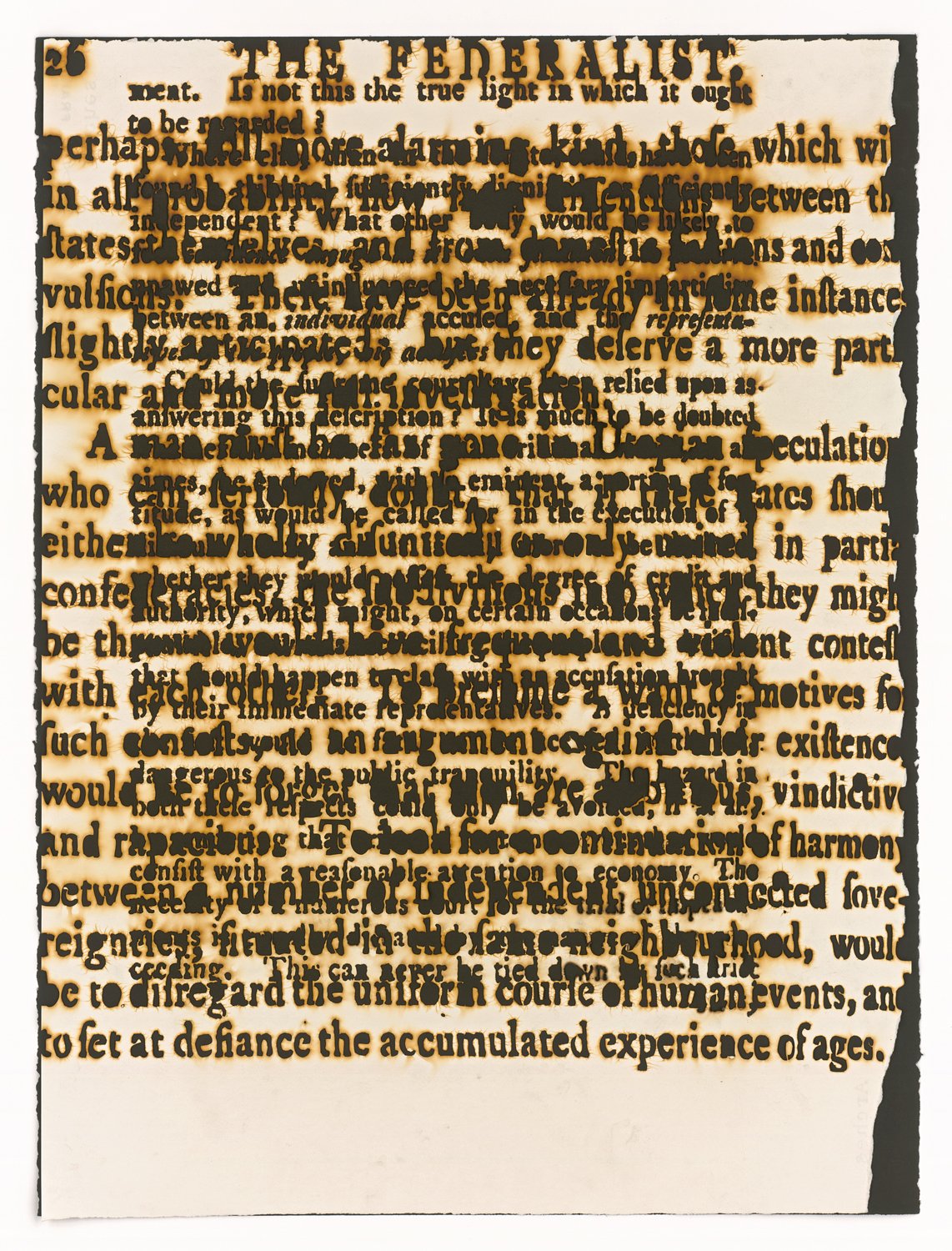

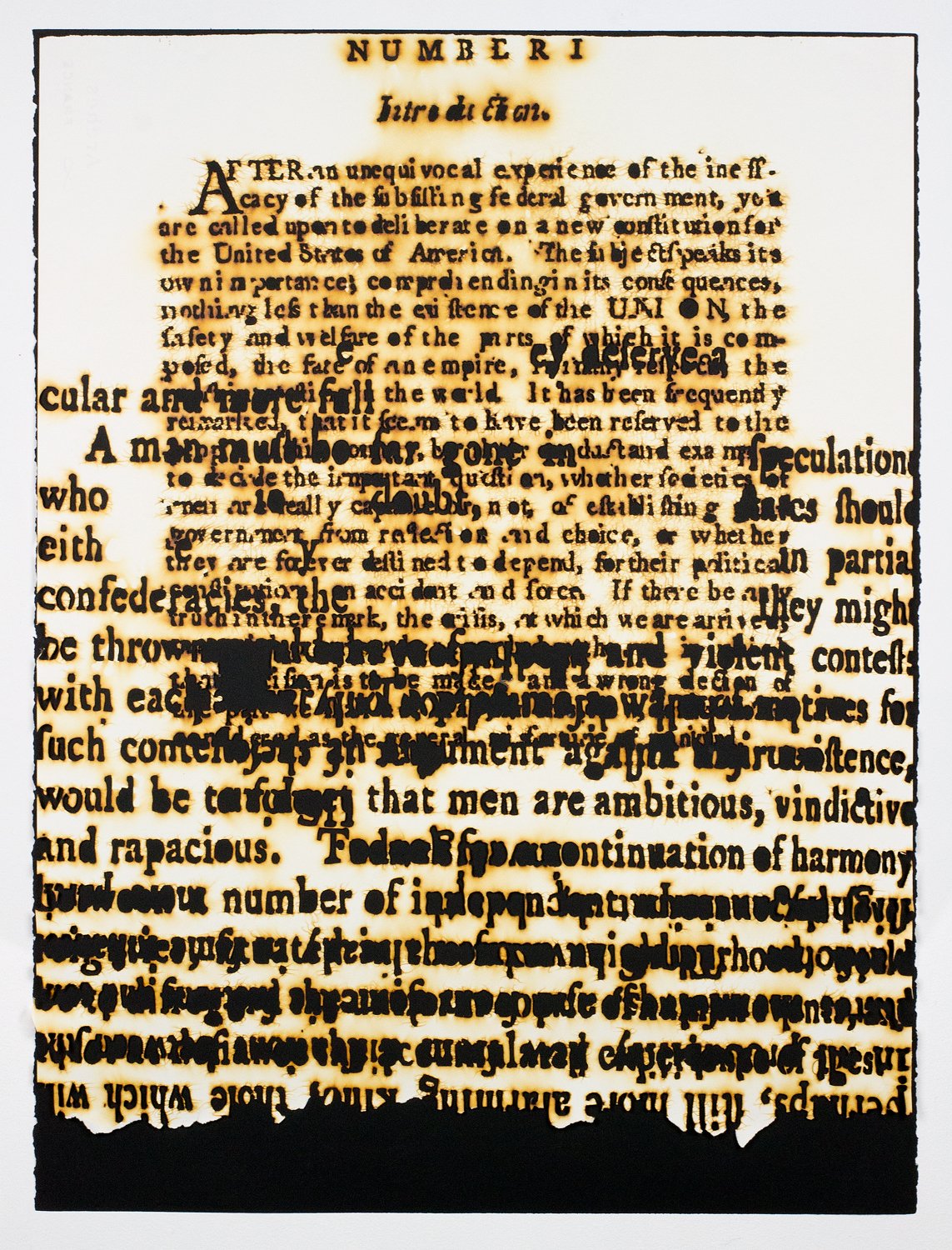

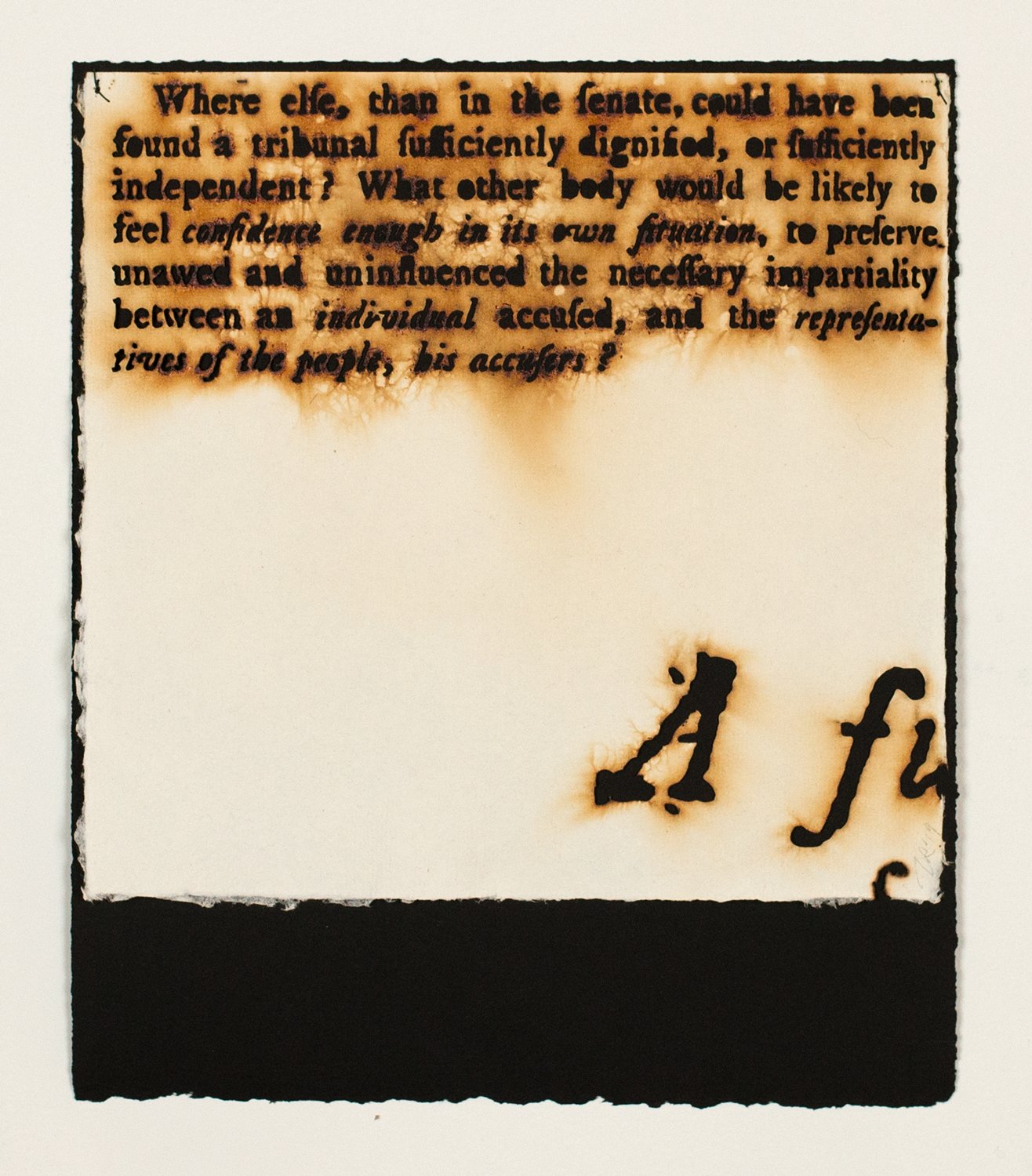

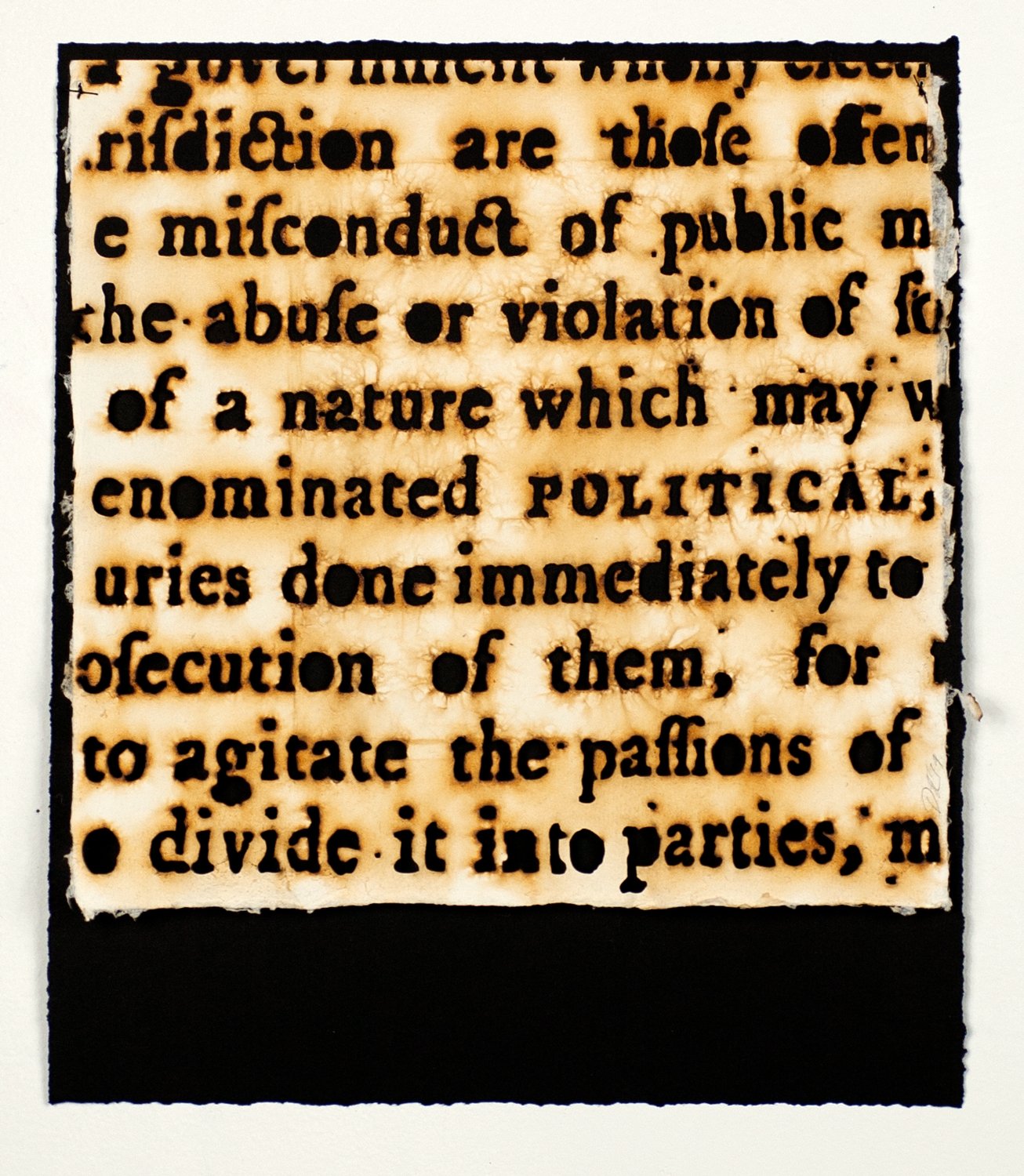

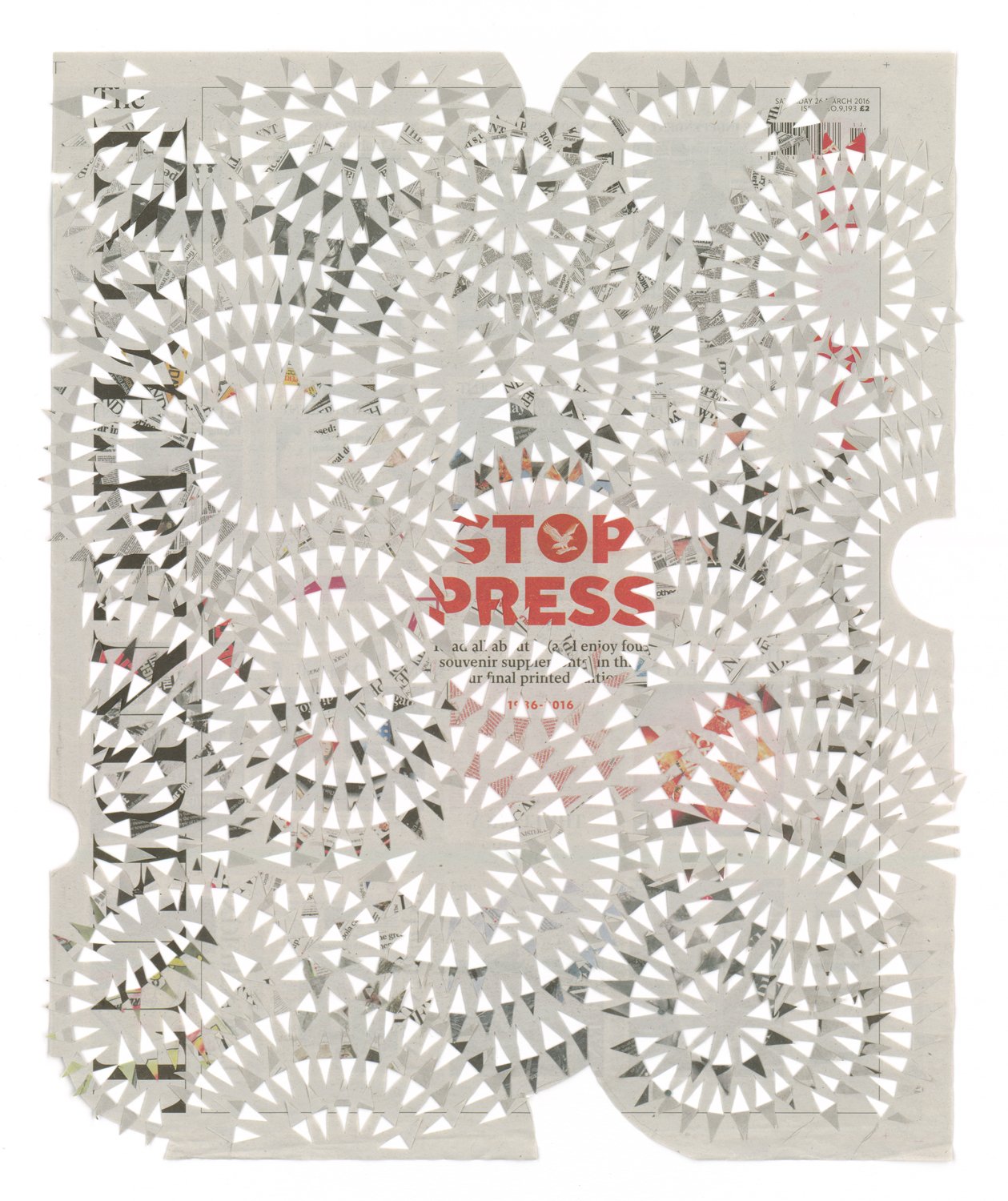

Donna Ruff is a visual artist who works with the printed word. She cuts, burns, and alters text, pushing the limitations of its ability to communicate with clarity. By removing portions of writing, she highlights that which remains, challenging the narrative as well as the narrator. Who tells the story of our country’s history? Who decides which news stories dominate the headlines? In her work with newspapers, Ruff overlays a geometrical design onto the front page, then removes the negative shapes by cutting them by hand. She leaves just enough behind that the viewer can discern the context, but also engage with the sacred geometry embedded in the design. These interlocking patterns are based in Islamic and Judaic motifs, evoking a contemplative state of mind as one grinds through the news headlines. This juxtaposition is at the heart of Ruff’s work: the contrast of positive and negative space, the removal of text to underscore the remaining content, and the defacing of the narrative to question its authority. Beyond contemplation, Ruff’s intention is to engage the viewer/reader in the stories and create a historical archive of the critical issues of our times. In another series, Ruff examines the Federalist Papers, the foundational writings of American democracy. She burns away the letters, literally removing every jot and tittle, leaving a ghost-like pattern that is a fitting metaphor for the current disintegration of human rights in our country. Ruff has worked in many mediums, always with text, language, and a heart for social justice. There is a beauty in her work that goes beyond aesthetic gratification, a thread of empathy that weaves through every newspaper headline, every burnt book page. This empathy speaks to the story behind the news, the interminable narrative of human dignity and suffering. Ruff presents these stories with grace and compassion, reminding us that in spite of the headlines, the prevailing narrative will always be our care for one another.

MH: You’ve shared some of your family history with me, and it seems that books and language are in your DNA. Have you always had a deep connection to books?

DR: Oddly enough, I’ve always had a deep connection to encyclopedias. My grandparents had a scrap paper company and my grandmother used to save encyclopedias from the shredder, taping pages back together. So even as a young child, there was a reverence for books. When we eventually got a set of encyclopedias, it seemed like an amazing gift. Then as an adult, I illustrated children’s books, so I thought about narrative and the sequencing of a page. I learned how to bind books in grad school, and then later found out that my grandfather was a bookbinder. So I have a lot of experience with books in various ways, and I think there may be something in my family history that sparked that connection. My mother used to say that this was why I became an artist, because they’d take me down to their scrap paper warehouse and give me a bunch of paper and I’d sit on the floor of the office and draw pictures.

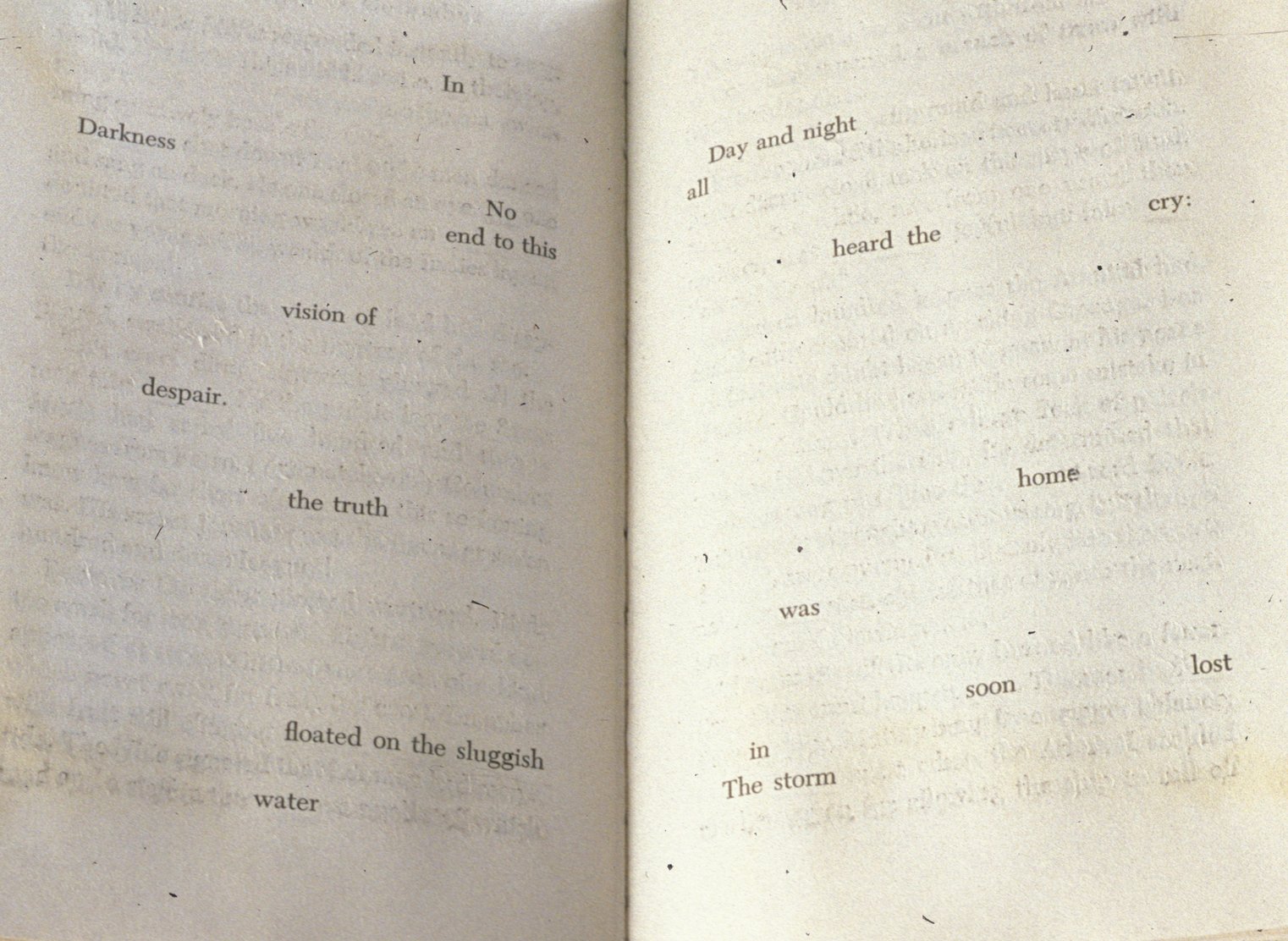

MH: I see your work with books as both additive and subtractive. You burn, scrape, sew, and paint over text, leaving fragments of language and meaning, open to interpretation. What’s going on inside your head as you engage in this process?

DR: I didn’t start burning until 9/11. Seeing the towers burn, thinking about all those people dying, you couldn’t help but be overwhelmed by it. This inspired me to burn as a way of processing the whole event. Then I met Willie Cole at Rutgers, and he was using hot irons and burning patterns on paper. That really stuck with me. When I started burning book pages, I transferred an image of a tree limb onto the page, then burned out the negative spaces. I liked the texture that resulted from the layering of text, shape, burned edges, as well as the subject of the book, which in this case was Freud’s “Interpretation of Dreams”.

MH: What did this work represent to you?

DR: My mother had just died of a brain tumor, but prior to that she’d lost the ability to speak, so I became obsessed with language, the brain, and cancer cells. I was interested in Rorschach blots and mirroring, and my designs reflected this. And it’s very satisfying to burn paper!

MH: There’s the sense that you’re sculpting with language, meticulously choosing what stays and what goes. Do you ever think of your process as an eclectic form of writing? Or are your editing choices purely visual?

DR: It’s definitely not just visual. With the newspaper pages, I cut the patterns by hand, so I’m constantly thinking about what I’m going to cut away and what I’m going to leave. I choose a front page that has an interesting photograph – for example, I often use photographs of migrants. Then there’s figuring out the pattern that I’m going to cut away, its placement on the page, and then once I start cutting, I think about leaving enough of the text that you can get a sense of the narrative from the words that are left behind. I’m constantly making decisions during my process, mostly visual decisions, but also of content.

MH: I’m intrigued by the idea of an artist using writing as the primary visual element in her work. A counterpart to that might be a writer who paints with language, creating an abstract painting with the written word. What is it about text that engages you?

DR: Early on I looked at artists who work with text, like Suzanne McClelland, who was working very abstractly and loosely with interwoven text. Lesley Dill was also a big influence. She worked with type and fonts in a way that the text became an image itself. Then my mother became ill and lost the ability to speak, so I never knew what she was understanding. This made me think about how much goes into the brain, and how much we process when it comes to language. I got interested in the idea of cutting or burning some of the text away, which has the effect of highlighting what’s left. And it pulls someone in closer to see what was left behind, so the work becomes more intimate.

MH: That’s one of the things that I like about text, the fact that it draws people into the piece. But for me, once they’re engaged, I don’t want them to fixate on the writing by trying to read or interpret it. It’s just another design element, not to be taken literally, as it were. How do you feel about this in your work?

DR: That’s interesting because in your work you’re literally building words with letters, so why go to all that effort if you don’t want them to read it?

MH: For me, it’s more about what’s being transmitted than what it’s saying. But with yours, people get in close to see what you left behind, and then they’ll probably try to read it. Are you good with that?

DR: I like when they get in close because they’re engaging with the story. If they see the front page of a newspaper, they might just give it a cursory glance, check out the headlines, and then turn the page. But if they see the front page with all these shapes cut out of it, they’re going to get in there and look carefully, and maybe they’ll question why I chose that page. Ultimately, I feel that I am a communicator. It’s kind of like writing a story with images because I want the content to be foregrounded and at the same time, I want the negative space to be foregrounded.

MH: Abstract art is like poetry in that it circles around a subject or sensation and creates an emotional response, but it’s not always the best tool for expressing a specific idea. Does your choice of geometric design reflect something specific that you want to communicate?

DR: Yes, in a sense. When I went to grad school after being an illustrator for so many years, I was trying to get away from anything that was figurative, because I felt like it was going to look like illustration. So I was exploring abstraction in a way that felt familiar to me, and it had to have some gravitas. I guess I’m kind of a serious person. The geometric abstraction comes from a lot of cultural influences. It’s very much about abstract ideas that are important to me.

MH: By overlaying the geometric pattern onto newspaper headlines, are you offering a counter-narrative to biased reporting?

DR: Not so much a counter-narrative as a suggested context. I don’t believe reporting is biased, but of course it’s mostly the violence that makes the news. I believe that we comprehend what we read according to our experiences and most people don’t know much about that part of the world. There is beauty and transcendence in the Middle East and the forms themselves are used not just in Islamic religious architecture, but also in synagogues and domestic architecture, just as the interlocking geometry is used on screens to allow breezes in and keep the sun out.

MH: It’s interesting that you overlay religious based patterns into the news. Do you see this series as a commentary on faith, not only spiritual faith but faith in the news media?

DR: The shapes aren’t religious based except in the sense that the repetitive shapes represent the unending nature of the universe, and their use in religious architecture is meant to encourage contemplation. I’m interested in the idea of sacred geometry and have done other series with circles and squares. Given my family’s reverence for the book, which is common to both Judaism and Islam, I guess you could view my overlay of these forms on the newspaper as a reverential act, but I think of it as preserving important moments in time as the news comes and goes in a flash.

MH: In that sense, you could take some of the articles that are buried deep in the paper, stories about people we’ve never heard of, and put an overlay onto that.

DR: I deliberately don’t use the inside pages. I have to use the masthead, because it is iconic, whether it’s the New York Times, the Miami Herald, or Wall Street Journal. The headline places it in history. The inside doesn’t have the same visual impact. And I like to think about the stories that make the front page: who gets there, how big is the type, how big is the photo, is it above or below the fold? I find that all very interesting.

MH: How do you hope that people will react to this series? What’s the optimum response?

DR: I want people to have empathy for what’s going on in the photograph, particularly the ones about migrants. The real value of that body of work is that it’s a historical archive. It’s something palpable that has frozen those stories in time.

MH: Burning has a ritualistic quality to it. In every religion there’s a sacrament that involves fire, burning away, destroying the obstacles that impair clear knowing. Is there an aspect of this in your work?

DR: Probably, but I don’t think of it in that way. Always in the back of my mind is the idea of book burning, like in the Holocaust, and even now, the censorship of texts. I mean, book burning is so symbolic! When you burn a book, you’re literally destroying a culture’s history and narrative; you’re destroying ideas. I’m conscious of the deep symbolism. Especially with the series I did in 2019 with the Federalist Papers – that was in my mind all the time. We are burning the Constitution; we are destroying our democracy.

MH: Would you talk about your recent large wall piece made with T-shirts? How does that fit in with the rest of your work?

DR: This is something that feels very close to me right now. During Covid I was cleaning out my closet and came across a lot of T-shirts from my old protest marches. I knew that I wasn’t going to wear them again, but I didn’t want to throw them out because they’re history. I decided to cut them up, then I dipped them in plaster and let them dry, allowing some of the words and images to show through. Finally, I put them all together on a wall, and it started to look like a memorial, so I stuck flowers on them, and invited others to add flowers to them.

MH: So Donna, you’ve had a long career as an artist, and I’m sure you have a lot more work ahead of you. And here we are in 2022, in unprecedented times, wondering what’s coming down the pike. Does it feel empowering or toothless to be an artist in the face of such uncertainty?

DR: That’s such a difficult question. I wouldn’t say that art is toothless, but it’s discouraging to think that what we’re doing isn’t making a difference. I demonstrated during the war in Vietnam, and we actually made a difference back then, but it doesn’t seem like that could happen now. There’s too much splintering and too much misinformation. So as much as I want to feel like what I’m doing makes a difference, I don’t know that it does.

MH: Does art have a purpose in a tenuous democracy? When we create artwork on a sinking ship, can we expect to keep it afloat, or are we just giving the passengers something nice to look at as they submerge?

DR: Like the orchestra that continued to play as the Titanic sank? [haha] I think that art is important, and it’s important now to keep it in front of peoples’ faces. But if you look at history, there were times when it was just a distraction from the real work of getting people to pay attention to what’s going on. I’ve voted in every election since I was twenty-one, and I believe the only way to make change is to vote. But now it seems like most politicians care more about their careers than about who they’re working for. But no, I haven’t gotten to the point where I’m thinking that we’re the orchestra that’s playing while the ship goes down, or the orchestra in the concentration camp.

MH: Then it sounds like you still have hope, even if it’s just a shred.

DR: I couldn’t get up in the morning if I didn’t have a shred of hope.

MH: I think that’s one of the hallmarks of being an artist, the fact that we hold onto hope until we simply can’t anymore.

DR: I feel so grateful to be an artist because I have something to keep me going every day, something that feels important – it’s certainly important to me. I’m still thinking, experimenting, still have energy for trying new things, and I still have hope that it will make a difference.

MH: I wonder if art has the capacity to change minds, to wake people up. Has that ever been possible? Or does the woke person gravitate toward evolved art because she’s already evolved? Which came first: the woke chicken or the enlightened egg?

DR: I don’t think people change their minds by looking at art. It’s long exposure to many ideas over time, and art is a piece in this process. The art world has become so diverse, very experimental, artists doing work that’s participatory and post-studio art. When it comes to art about social justice, I believe that creating empathy is really the key.

MH: I see art as the antidote to cynicism. We’ve become so jaded, so divorced from trust in our government and news sources, that we have little faith in any form of communication. Art has become essential, not to match the new couch, but as a vital expression of integrity. What are your thoughts on this?

DR: I agree that art is more than what looks good over the couch. But there’s been a lot of interest again in abstraction, so maybe people are turning away from social justice issues in art, and they’d rather have the nice shapes over the couch. I do think that art can bring a ray of light into peoples’ lives, even if they’re using it to avoid the dark. That’s not a bad thing. If everyone becomes so cynical that they don’t do anything, that’s not good either. That’s maybe even worse.

MH: When artists go into their studios and dive into their work, they may not be making political or socially responsible work, whatever that is, but they’re creating authentic work. And I would argue that this very act provides a counter-narrative to the shifting political truths that we hear about constantly in the news. How do you regard authenticity when it comes to your work?

DR: The word authenticity is very loaded right now. I’m true to myself and my own vision, and that’s important to me. One of the things that makes us so vulnerable as artists is that we’re being honest in our work. We’re saying, this is what’s important to me! This is what I believe! And if someone’s not interested in it, it’s hard not to take it personally. That honesty is the kernel of what’s so engaging about art. You can see it. There’s a gravitas in good work that you can always respond to.

MH: Art may not have the ability to change minds or wake people out of their sleep, but it tells a different story than the mainstream narrative. So when our ship does indeed sink and the next civilization paddles up to inspect the flotsam, they’ll see the art and know that there were some among us who cared about truth and basic goodness.

DR: So when they come across Jeff Koons’ giant “Puppy”, they’re going to assume that this is what we were all about? [haha] We see the art of cultures from long ago and we put our own meaning on it. It takes an art historian to know that those Greek sculptures were painted at one time. We have a sense of beauty, which to me is still the guiding force in everything I do. That’s part of my core; I can’t put stuff out there that doesn’t have a certain beauty to it. I want it to be alluring – I want people to get pulled in.

MH: What do you want your flotsam to say to future generations? What mark would you like to make?

DR: Empathy is important to me. But in the end, is anything we make that important? I’m happy that the work has been collected by some museums, so they’ll take good care of it. But I’m not so sure of my own value in this world to think that it’ll be important for someone to dig up something of mine. I’m a miniscule part of the big picture.

MH: What’s the best part about being an artist?

DR: Making art, making anything really, is deeply satisfying. The fact that I have the skills and focus to make beautiful objects is a great blessing, especially as I get older. I can’t overstate how important that is to me. I like to think that what I’m doing is bringing something positive to the world that wouldn’t be there otherwise.