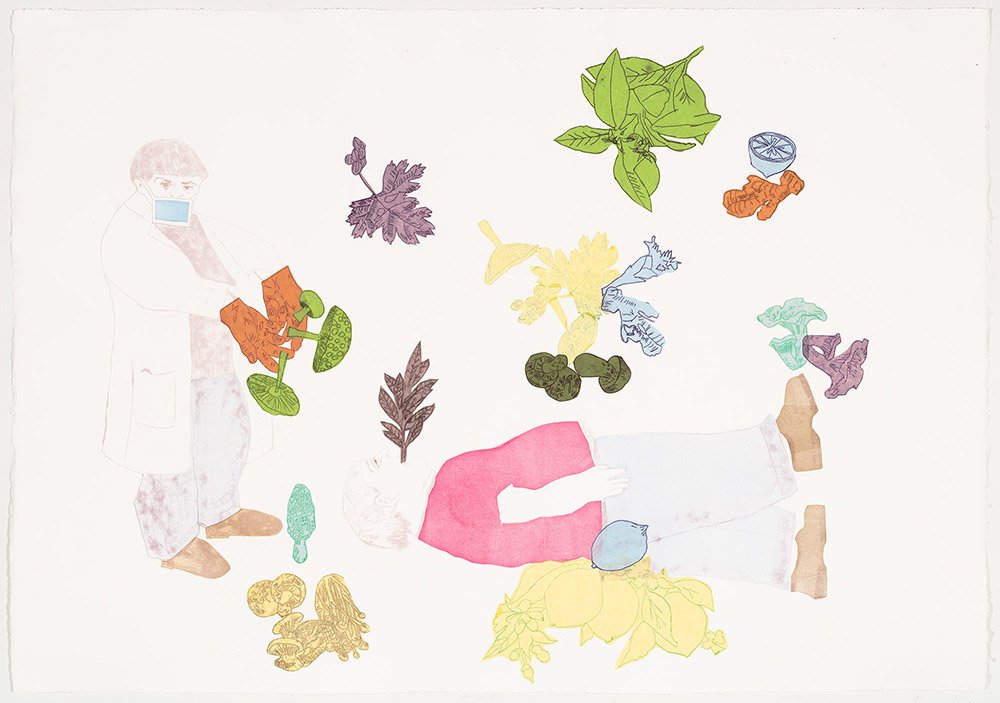

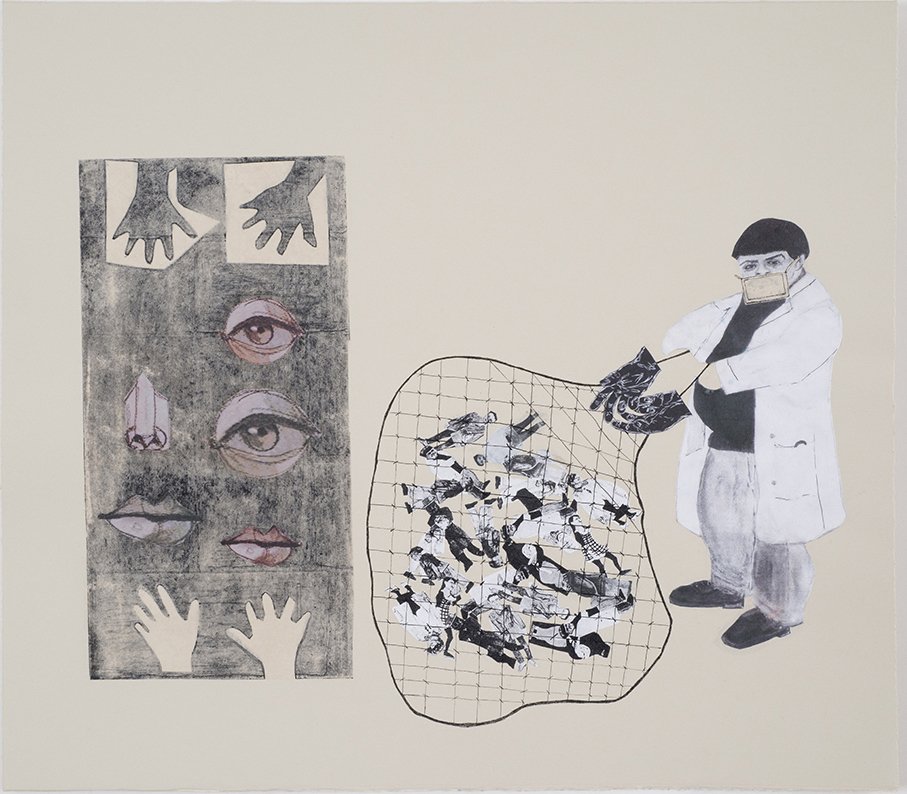

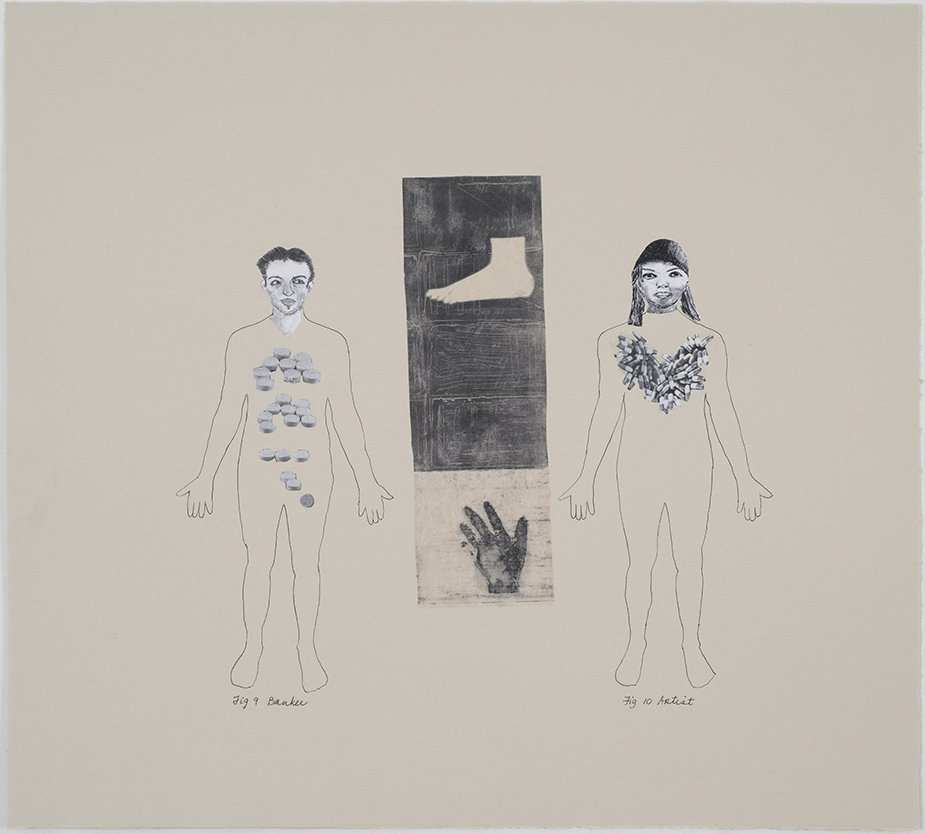

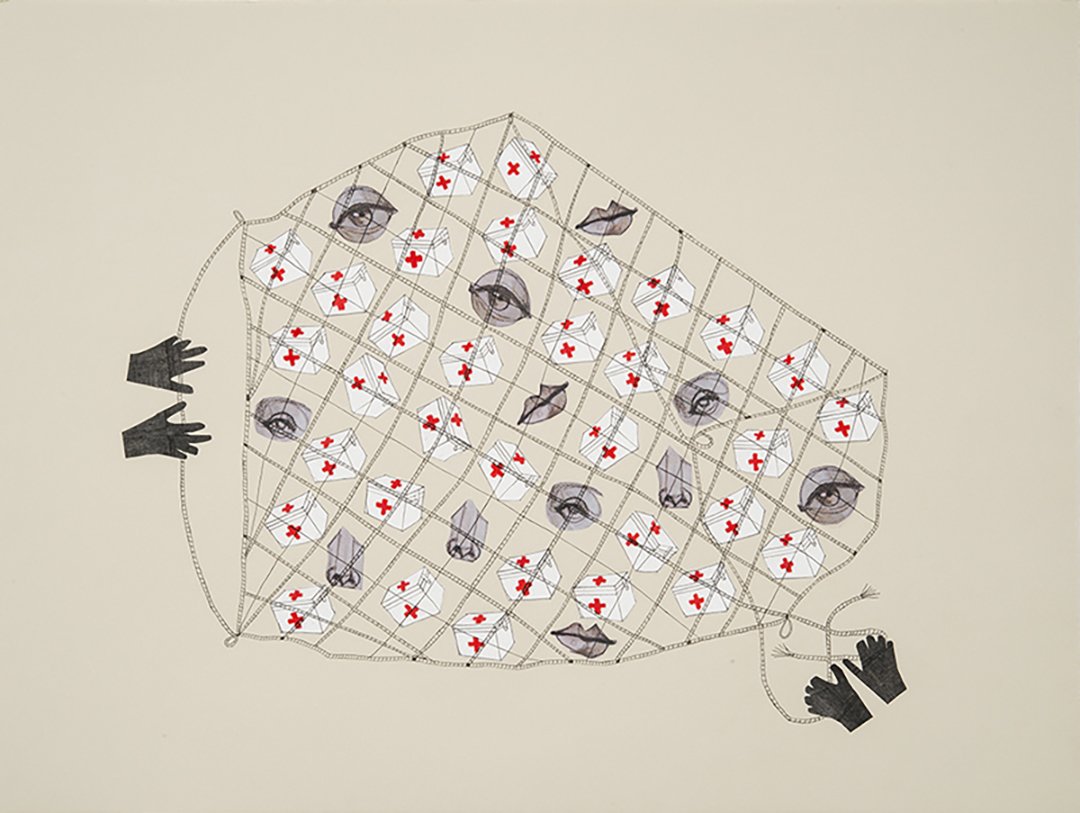

Leslie Kerby is a Brooklyn-based artist who concerns herself with the complex socioeconomic systems that impact our lives daily. My eyes glazed over when she brought up the subject of supply chain management, and I wondered what would entice an artist to take a running leap into the tangled web of corporate culture. But her enthusiasm is contagious, as I discovered when she explained the intricacies of the shipping container industry. It’s clear that Kerby enjoys the reactions to her wonky subject matter, which she talks about with great humor. Her interest in these systems began in her early twenties, when she was a social worker and had to navigate the social services sector. Later, her interest expanded to the complex networks that make our lives run smoothly, such as the medical care industry and the funeral and burial industries. Kerby’s intention is not to point out the failings of these systems; rather, it’s to bring awareness to the labyrinthine networks that are indispensable to our everyday lives. Through her various mediums of paint, printmaking, collage, video, and sculpture, Kerby makes her subject matter visually appealing, which in turn makes one want to understand the container industry and its discontents. One thing that stood out clearly during our conversation was Kerby’s genuine warmth and care for others. Her years in social service gave her the skills to listen closely to the back stories of peoples’ lives, and to make connections in unexpected ways. This shows up in her curatorial practice, where she juxtaposes artists who explore similar topics with different visual languages. Kerby’s curatorial practice, along with her art practice and frankly her life practice, is about building the kind of connections that create community and make us want to help each other.

MH: You’re an artist and a curator, but in a previous life you were a social worker, and you also worked in corporate communications. How do your former careers inform your creative work?

LK: They do in so many ways. In my early twenties, right out of college, I was a case worker at a social services agency. I had eighty people who I was responsible for, and I often developed intimate relationships with them. I learned how to sit and listen, how to understand where people were coming from, and how to think on my feet during a crisis. The situation was often different than when it was first presented, so I learned to listen to the back story that precipitated the crisis. I also spent some time interviewing people for food stamps, which exposed me to that whole social system. I became interested in the social networks and systems that we don’t think about day-to-day, that have a huge influence on how we operate in our lives. My challenge as an artist is to find interesting ways to present this information in a way that will engage people and get them talking about it. I was also in corporate communications, a focus group moderator at an advertising agency, the assistant director at the Hunterdon Art Museum in Clinton for a few years, and I worked at the Johnson Museum at Cornell on their development team, and on and on. I have a very long resume!

MH: It’s sort of humorous if you look at this long list of things that you’ve done. They’re so unrelated to the art world!

LK: Yes and no. The art world is also full of people, and there are surprising ways in which I draw on all these experiences, no matter what it is that I’m doing. I also represented graphic designers for eighteen years, helping them build their careers. That was a stepping stone into the world of paper and design. I started making small, abstract collages, which became greeting cards, which turned into a greeting card business! [laughter] I sold a line to museum shops and other arts institutions for about eight years and exhibited at the stationary show at the Javits Center.

MH: Is your work with hidden systems, like the shipping industry for example, a creative response to the years that you worked in social networks? I’m wondering if it got under your skin, and you started seeing connections everywhere you looked.

LK: I think it’s always been a part of my general interest. I read widely and I like a challenge, and for me it’s interesting to talk about things that seem like they’re in the background, but have a big impact on what we’re doing day-to-day. I get excited about presenting this information in an interesting way, then hearing the responses to my work, and having conversations about it. I guess I’m just a social being.

MH: It’s interesting that your subject matter is based in left brain logic, and your creative work is based in right brain intuition. How do you think about this contrast?

LK: I like to think that I’m engaging both sides of the brain. I have an analytical side to my personality, and I’ve always had a creative side as well, but I didn’t express it visually until I started making the greeting cards. That was my entry into the visual realm, because these small collages became larger images, and then I had someone interested in showing those in a gallery.

MH: It sounds like you don’t really see the left brain/right brain contrast, but you see it as more free flowing.

LK: It is, and always has been. I used to express my creative side through sewing, creating my own patterns for clothing, cooking, that sort of thing. In the early days when I worked at companies, people would ask me if I was a lawyer because of the language I used, so I know I have a strong analytical side as well. Maybe the two sides are more blended now.

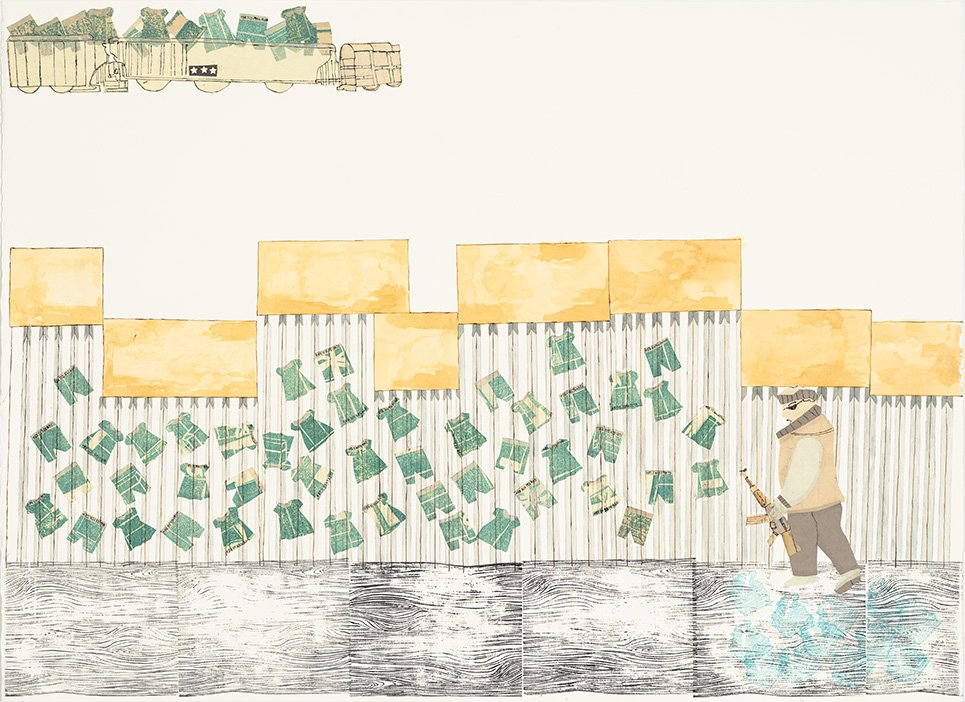

MH: Can you talk about some of the networks that you’ve explored in your work? For example, you became engrossed in the shipping container industry and supply chain management. Most eyes glaze over just reading those words, but you took a deep dive into its intricate structures. I’m curious what drew you into studying this subject?

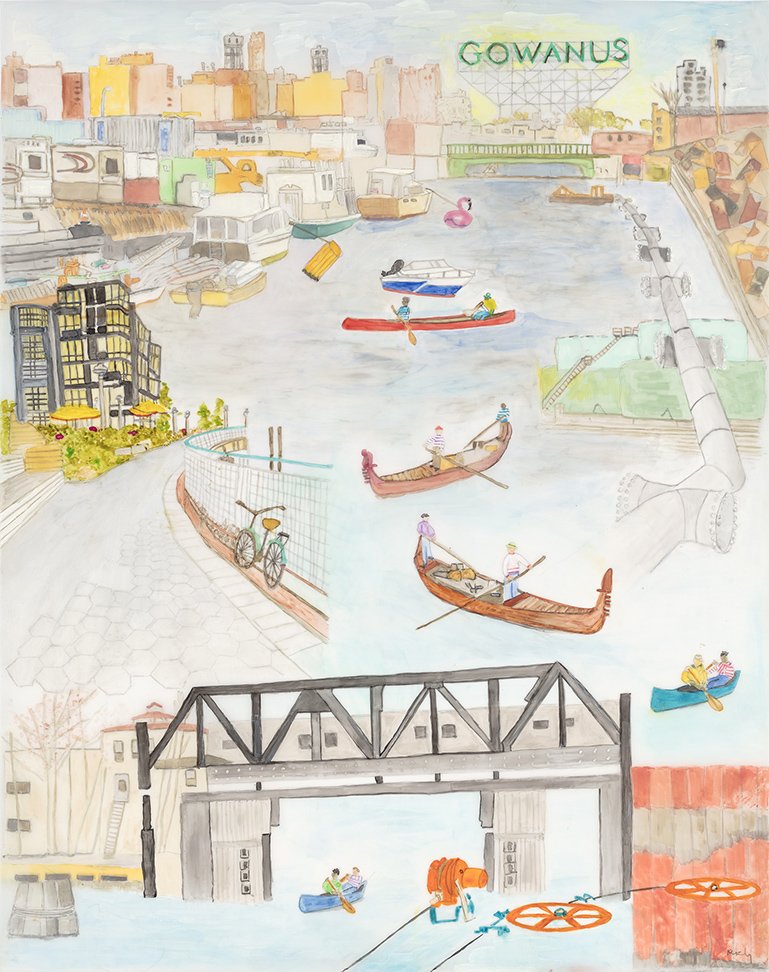

LK: It started with observing that shipping containers were becoming a part of our everyday lives. I started reading about the industry and learned that shipping containers were being used in tent cities, and as vehicles for hydroponic farming, and I saw that they were being used for markets in Brooklyn. I read up on the history of the shipping container industry, which got me interested in the current system of supply chain management. This system maximizes inventory by keeping it moving out of warehouses, so companies don’t have to store so much stuff because they keep it moving throughout the world.

MH: Was there a graphic aspect to the shipping containers that also intrigued you? Do the systems that you choose to explore also have a strong visual component that engages you and informs your work?

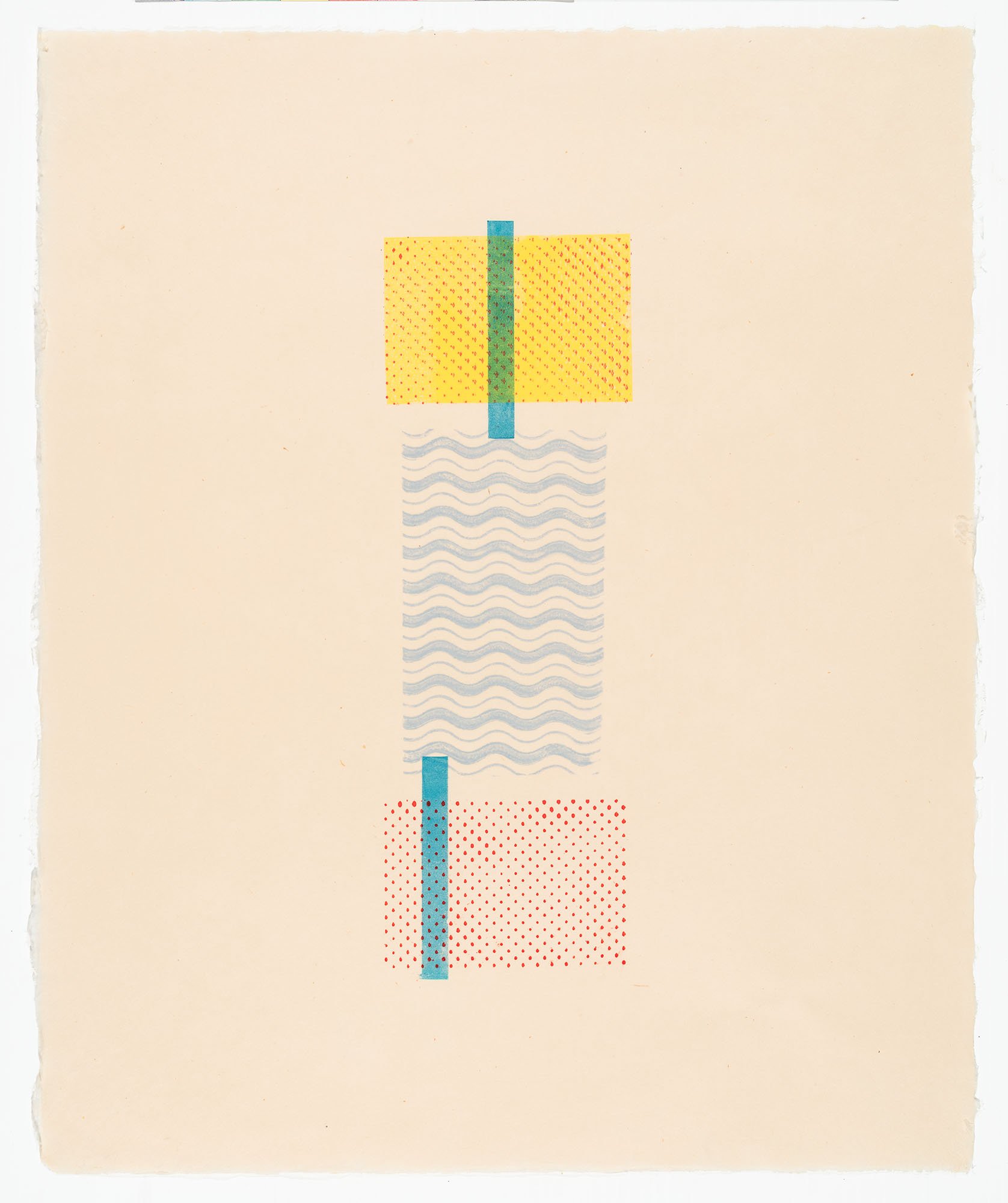

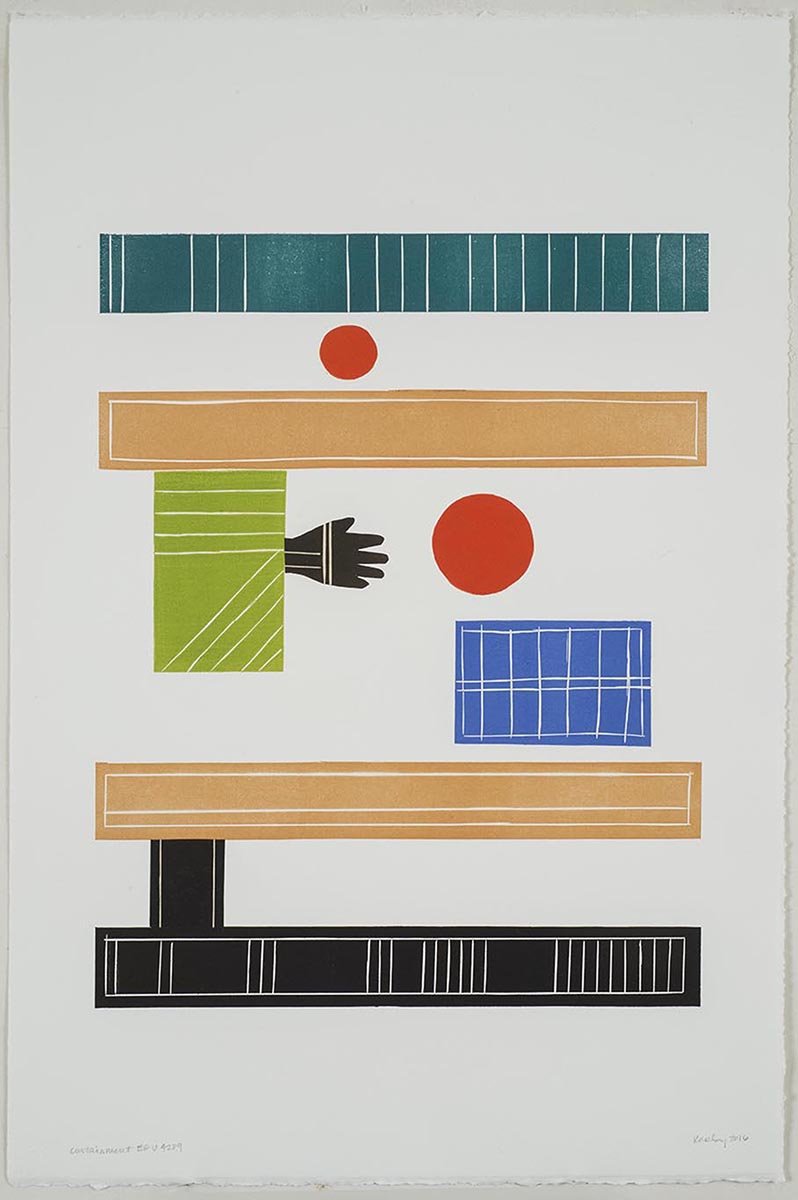

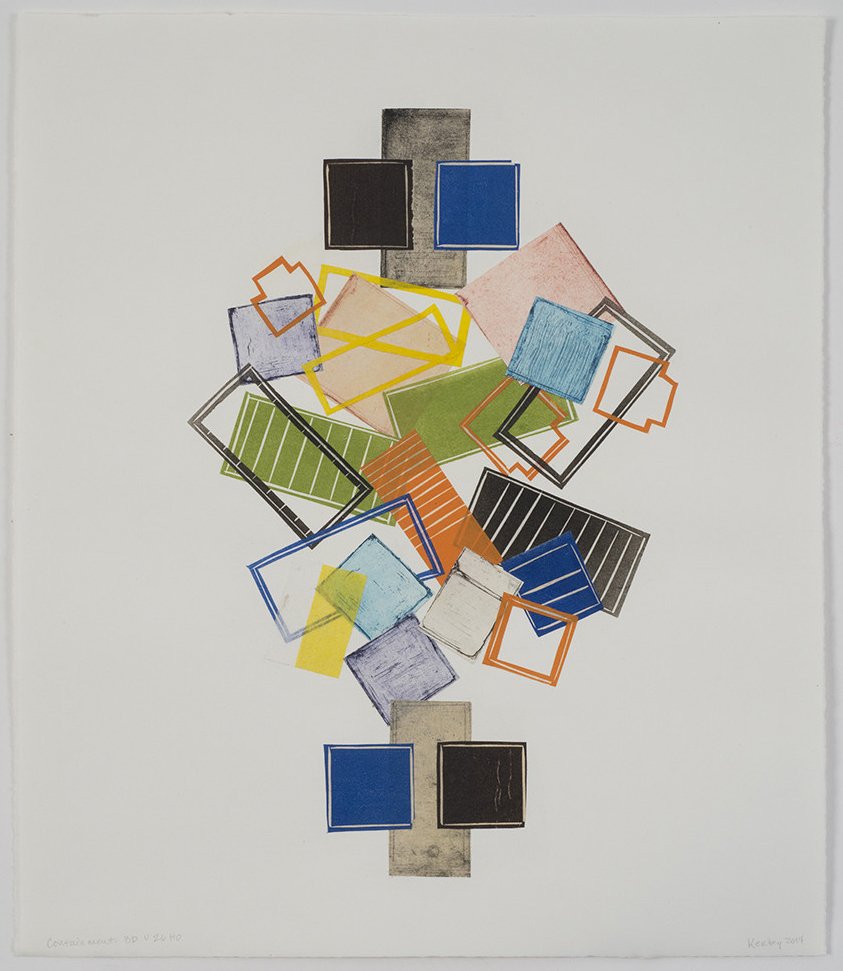

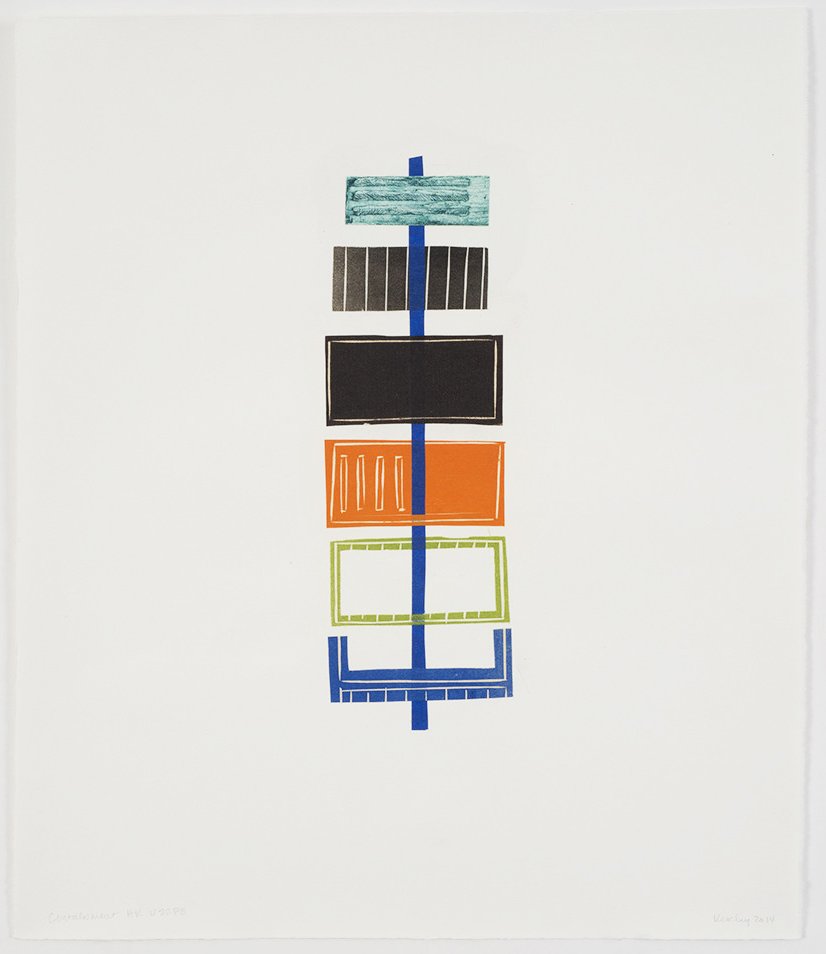

LK: Yes and no. Certainly for the shipping containers, there were graphic design elements that I was drawn to, like their shapes, colors, how they’re stacked, the letters and numbers on the sides of the container, even the names of the companies. I found all of that very appealing. The work that I’ve done with cemeteries was also visually intriguing because the headstones and monuments can have interesting shapes. But when I came to the medical industry, it didn’t have a strong visual component, so it took me a long time to figure out how I wanted to deal with that.

MH: As you study these obscure systems and begin to grasp their complexities, are you more apt to find order or chaos? Are you expecting to find one over the other?

LK: It’s not that I’m expecting to find chaos, it’s more that I’m sensing that we’re at a significant moment of change. Taking on some of these systems is a big task, and collectively we may need to think about how we want to approach them differently, or what we might want to demand from the systems. I’m not looking at it as though there’s something wrong, but that something big is happening and it would be interesting to have a conversation about it. I’m trying to be open to what’s there.

MH: Do you ever feel like it’s too late for these conversations?

LK: Things change very quickly! By the time the public becomes aware of it, it’s almost too late. But I’m an optimist, so I try to find a way to be positive, and maybe that’s the point of my artmaking process. These are difficult and complicated subjects that people may not want to bother with, but maybe we can bother with them and have a few laughs while we discuss them.

MH: Do you get the sense that all these complex organisms are working in unison, or are they hopelessly out of sync? For example, is the medical industry compatible with the body’s immune system? And is the shipping container industry supportive of the democratic system of government? One likes to think that humanity is well served, but often that’s not the case.

LK: I think that there are misalignments between them, but I believe they could be brought back into sync. These systems are big and unwieldy, but the crux of the problem that underlies everything is the inability of people to understand other people.

MH: What do you think is the underlying cause of the breakdown of systems?

LK: I’d say the baseline is money. There’s money to be made with the systems, and that ends up being the driving force behind the ways that they get completely out of whack.

MH: With your skills and knowledge, you could have had a flourishing career as a supply chain analyst, but instead you chose to be an artist. What pulled you in that direction? Was it the salary and benefits?

LK: Ha! Hardly. I could have gone in a thousand different directions with my experience. I’d been representing artists and graphic designers for many years, and I’d been doing a lot of things for other people, which is a part of my personality and gives me great joy. But I felt like there was something I wanted to express, and art making turned out to be the thing I wanted to explore.

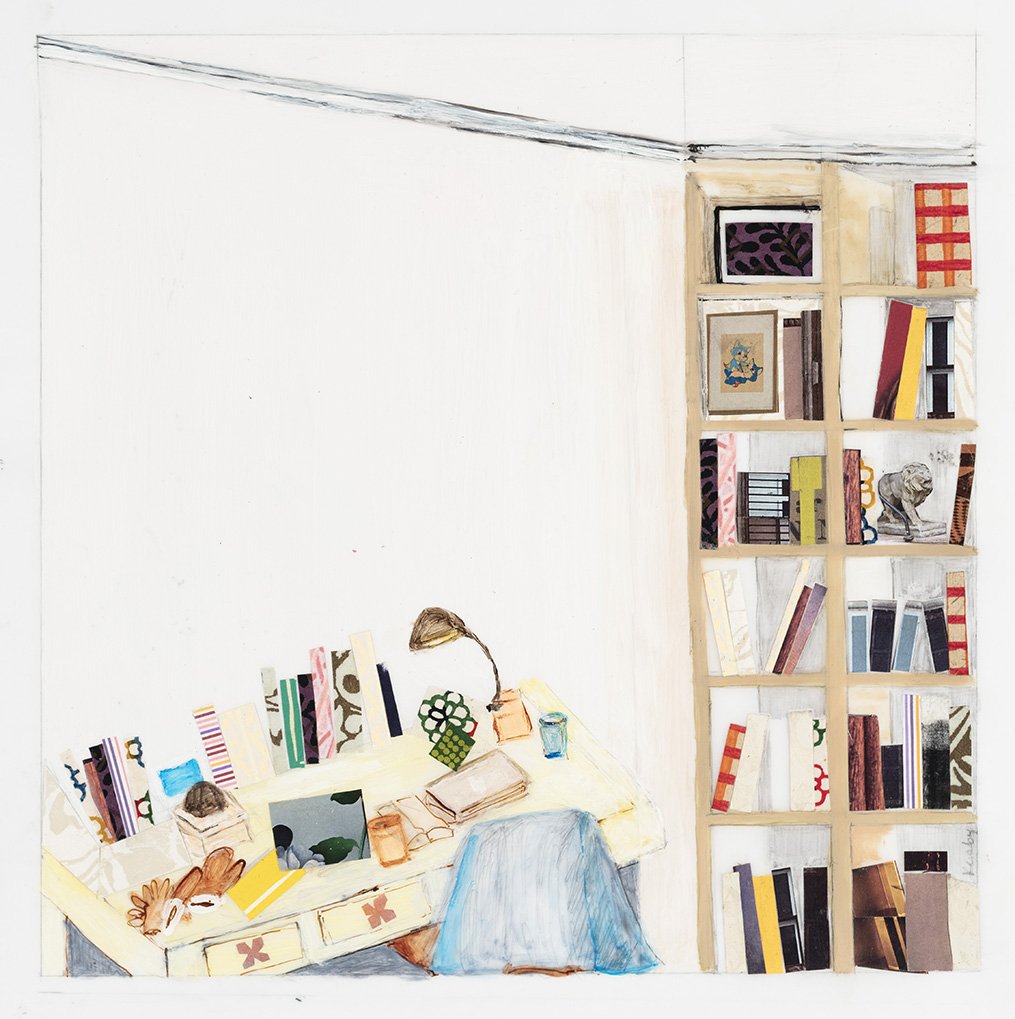

MH: What’s your studio practice like? You say that you get restless working with one material, so you work in a variety of mediums and styles. How do you choose which medium to use on a series?

LK: I always try to find the best material to articulate my subject. I feel like almost daily I’m jumping off the diving board, because I’m always experimenting, trying new mediums and new approaches with familiar materials. I also love collaborating with artists, and that’s opened a new world for me. I started working with Lianne Arnold, a video artist, and Elisheba Ittoop, a sound designer, and the three of us created the shipping container project. [see video below] Lianne and I subsequently worked on a video that explores the mechanics of the medical industry. I love collaborating because the other women come up with great suggestions that I never would have thought of, and this enriches the project. And I have absolutely no problem touting their praises because we’re all in it together.

MH: Do you have an ego?

LK: Yes, I do have an ego, but I enjoy working with other people so I’m happy to share in that journey. If they’re excited about working with me and coming up with this way to present something, I’m gratified.

The World Contained, II by Leslie Kerby, Lianne Arnold, and Elisheba Ittoop

MH: Some of your work hints at better ways to conduct our interpersonal relationships. There’s the issue of how to negotiate public and private spaces, and there’s a series that you did that introduces new ways to “bury” our dead. Would you talk about that a little?

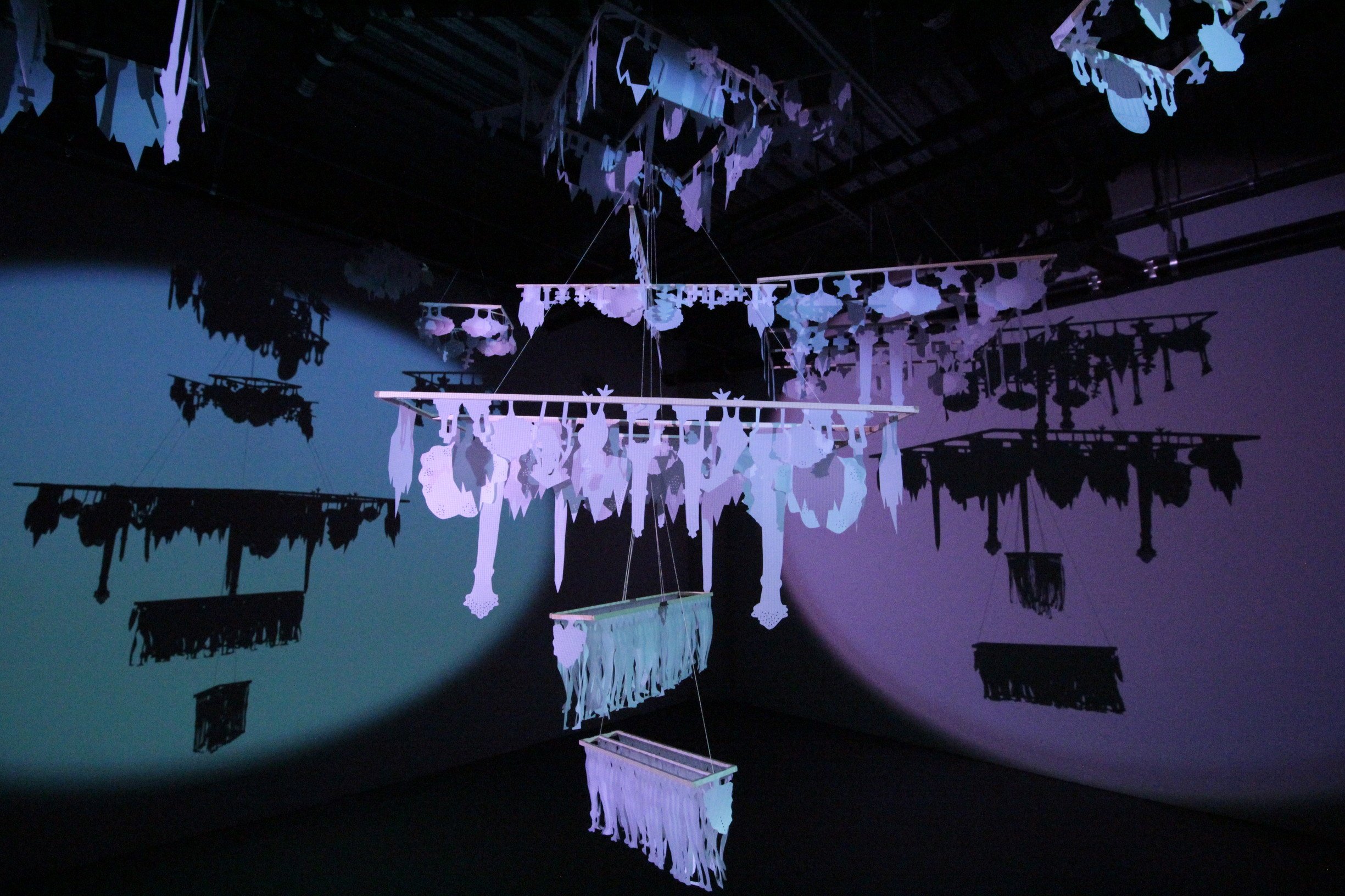

LK: My interest in cemeteries initially had to do with access. Who has access to the cemetery, and who can be buried there? Then I became interested in the social networks found in cemeteries – there are the founding families of the town here, the people with money here, and the poor families over there. And I thought, we’re doing the same thing in death that we do in life! And then there’s the fact that cemeteries are becoming obsolete because most have reached their capacity. How should we think about memorializing our loved ones if the physical cemetery isn't going to be available? I explored these ideas during a residency in Virginia, cutting out silhouettes of monuments in vellum and making structures that I hung in my studio as mobiles. This instigated some great conversations about memorials versus monuments, and the funeral industry in general. Then I went on another residency in Dumbo and worked with Lianne on a video that was projected onto the mobiles. The response was overwhelmingly positive, and all this was pre-Covid, so I’m dying [haha] to present it to a wider audience.

MH: There’s the stereotype of the artist as a harried introvert who goes into her studio, locks the door, and paints in isolation all day, every day. This doesn’t sound like you. How important is community and connection for you?

LK: Community is everything for me. When I started showing my work in galleries, I realized that I didn’t have a network in the art community, so I was going to have to get myself out there and meet people. As a result, I know a lot of people. When I ask someone to work with me or collaborate on a project, they often know me and they’re receptive to it, and I find that very gratifying. I also have days when I get into working in my studio. I love the quiet and the ability to think things through, but then I quickly get to a point where I feel like I’ve got to get out there and talk to people about my ideas. I feel like I can’t exist without community, honestly.

MH: When you curate, you create interesting conversations between artists through their work. One could say that in your studio practice you’re depicting systems, while in your curatorial practice you’re creating them. How would you describe your practice as a curator?

LK: I’ve had the luxury of being associated with this project space in Midtown that a lawyer friend has, called Project: ARTspace. I’ve been grateful for the opportunities to curate shows without any directive. When I put the shows together, I find artists whose works touch on the same topic but in different ways. I try to create interesting juxtapositions, exploring the connections between works that someone else might not have put together. And I’m so happy when people get the connection; it’s very gratifying to me.

MH: In your curation practice, you’re creating connections in real time. When you’re in the studio and engaged in your creative work, do you have the sense of being connected? And if so, to what?

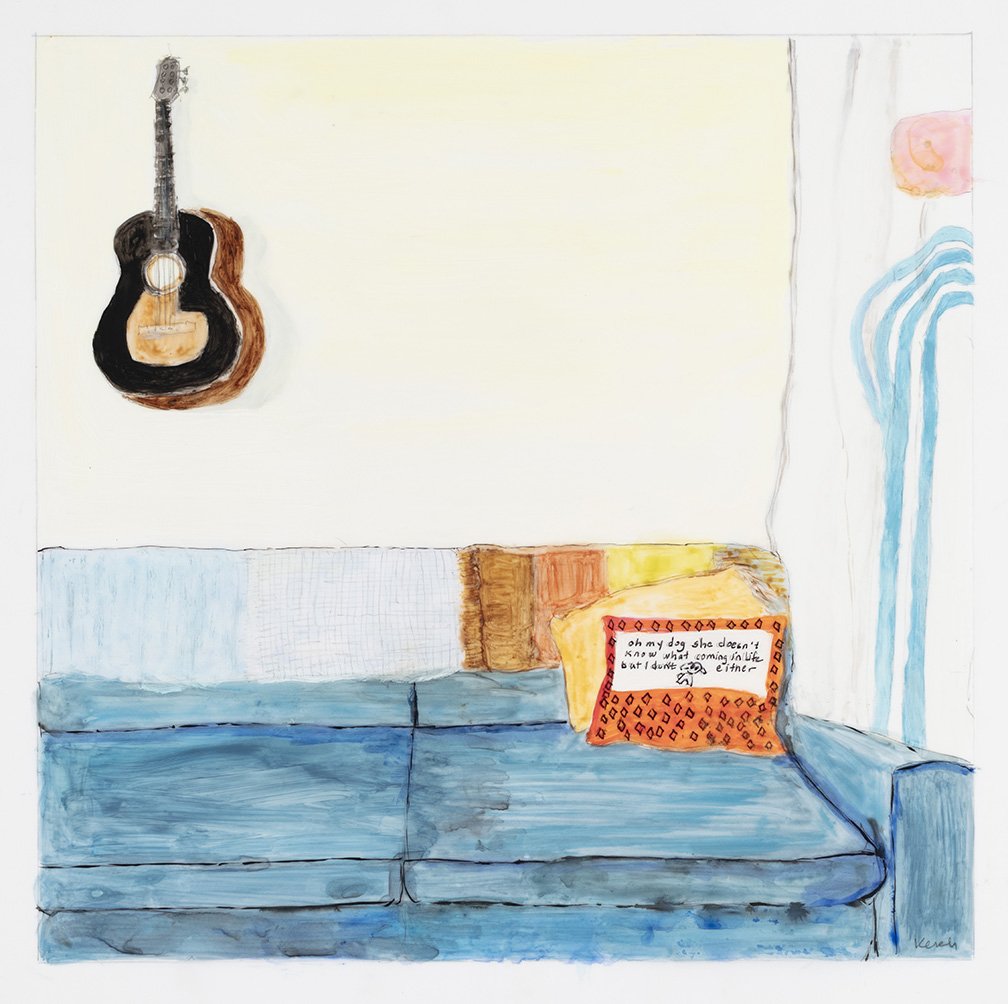

LK: I can easily work for eight hours at a stretch, and I love those days when everything is flowing. It feels like what’s in my head is coming out through my fingers; things feel easy, and they make sense in the bigger picture of the series that I’m creating. It feels magical, and I get those days fairly often. But it’s also important to me to go out and see the shows as a way of staying connected with the current conversation about art. I also read a lot of the art magazines, like Hyperallergic and Two Coats of Paint and the various interviews, because it also helps me to stay up to date with the larger conversation.

MH: What’s the best part about being an artist?

LK: Getting to do what you want to do. There’s incredible freedom in getting an idea and then expressing it. And then all the artist friends that I’ve made who sustain me and feed me, and all the friends I’ve made through making art and collaborating. I feel like my life is full because of that, and it takes me to places that I never would have gone or sought out. I also find that no matter where I go in the world, I meet people and make great connections. Honestly, that to me is so thrilling.