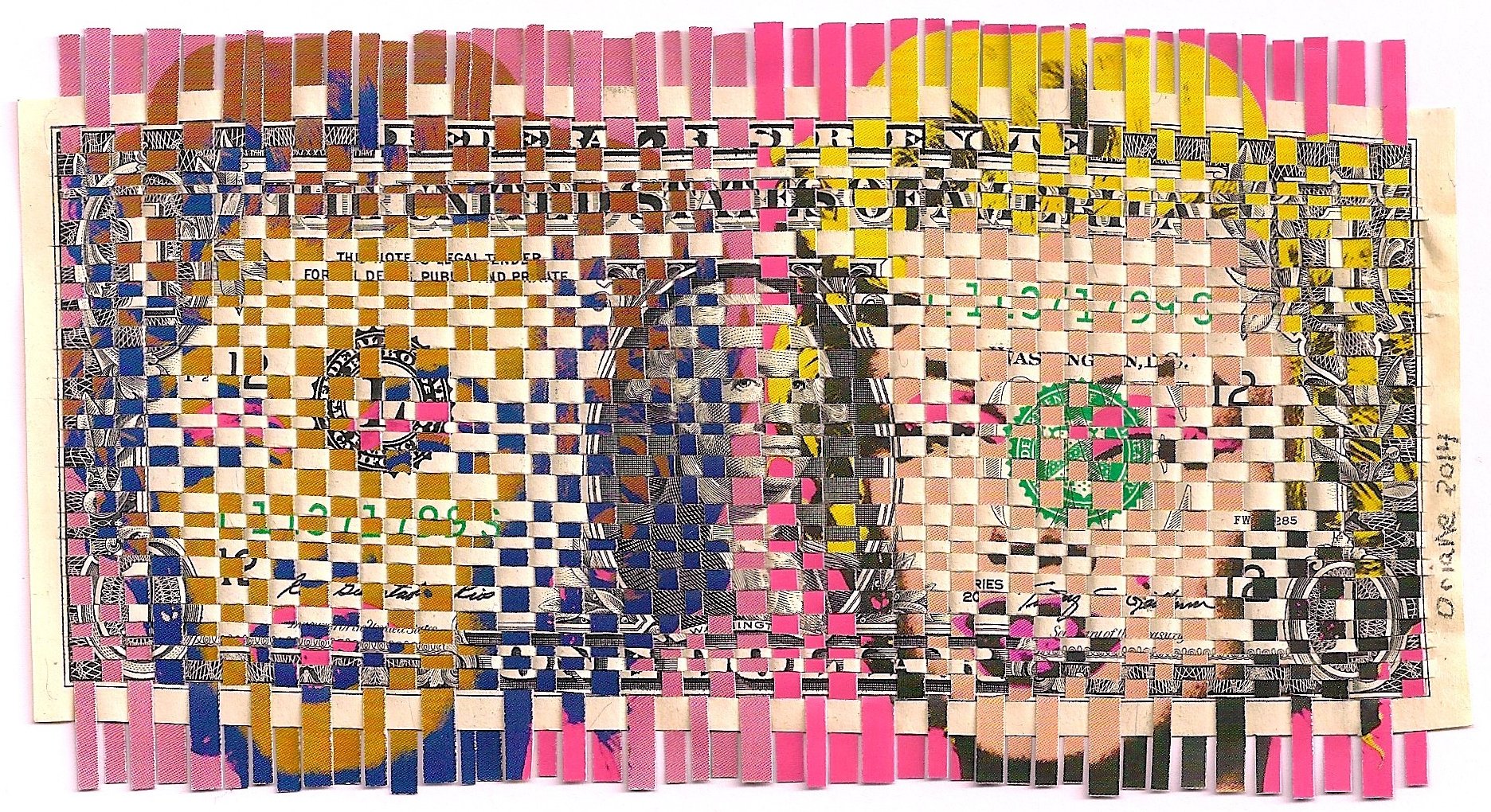

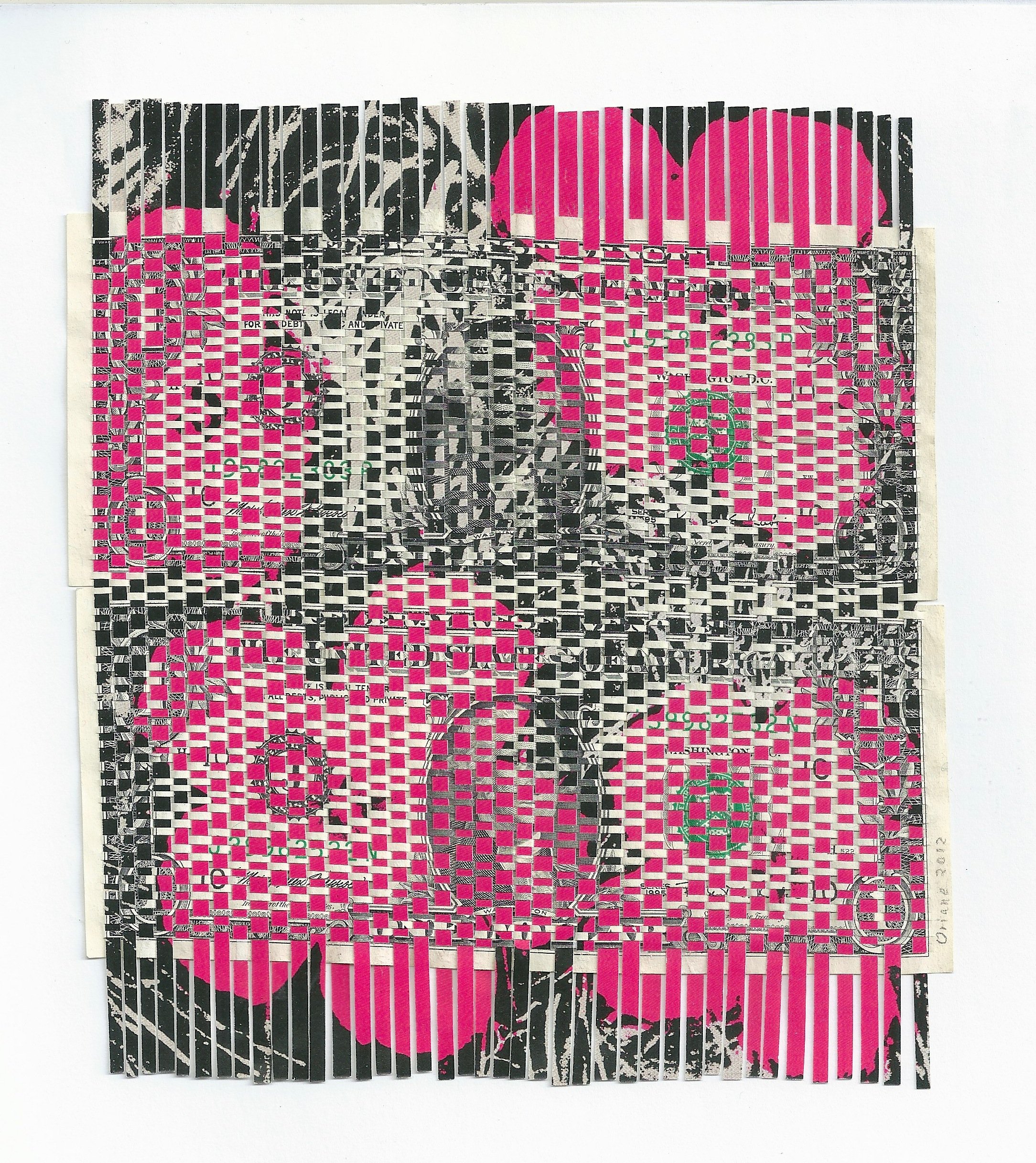

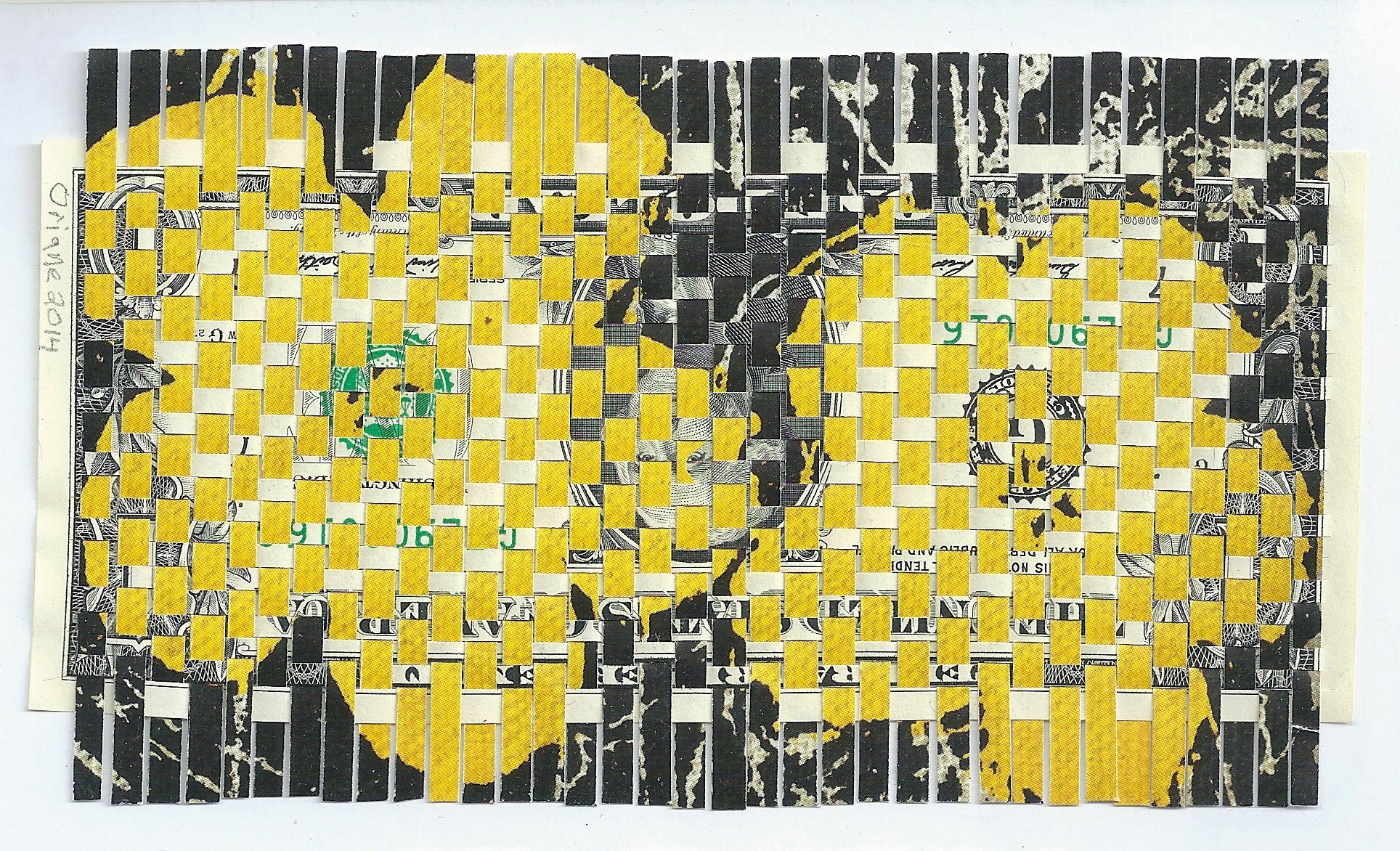

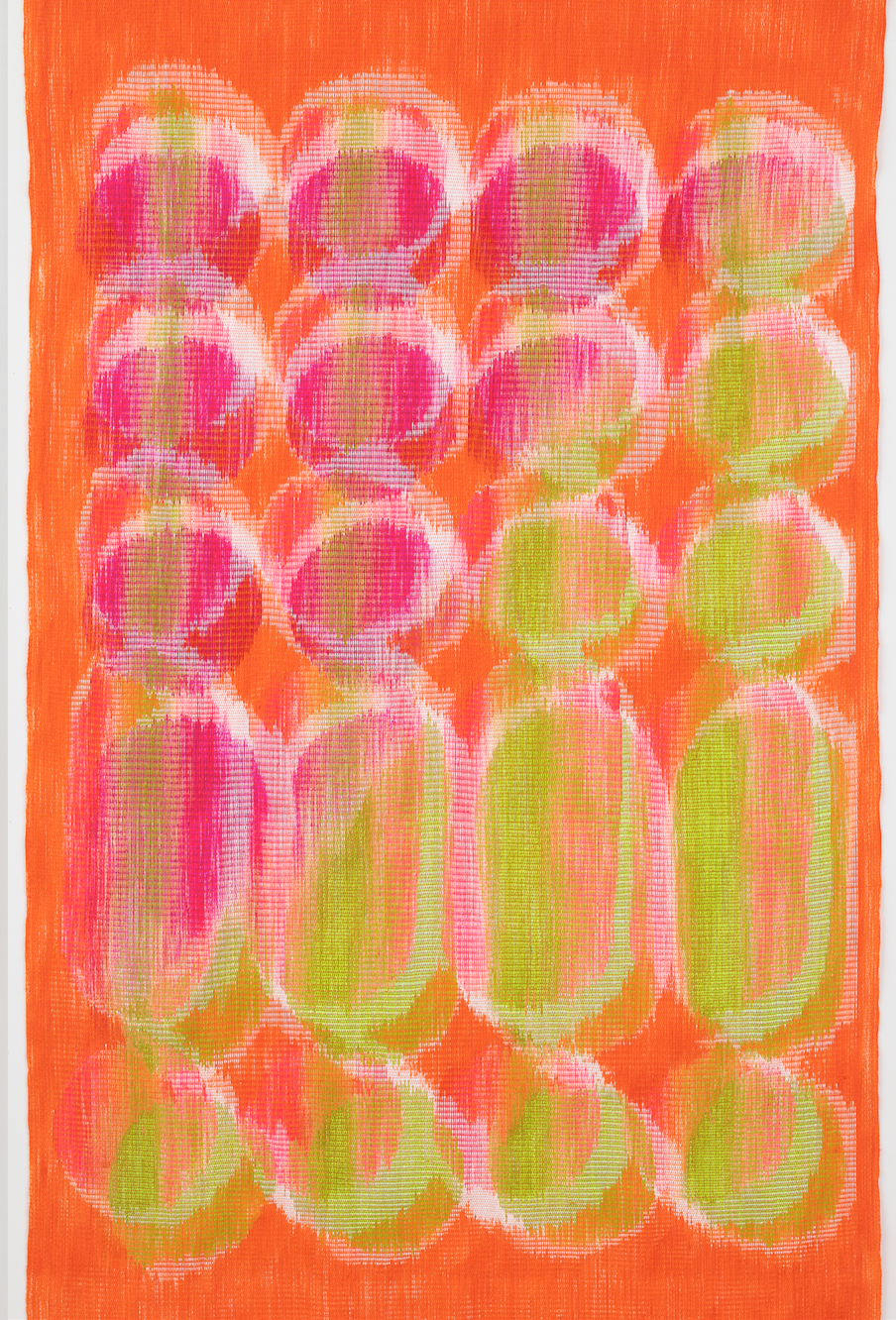

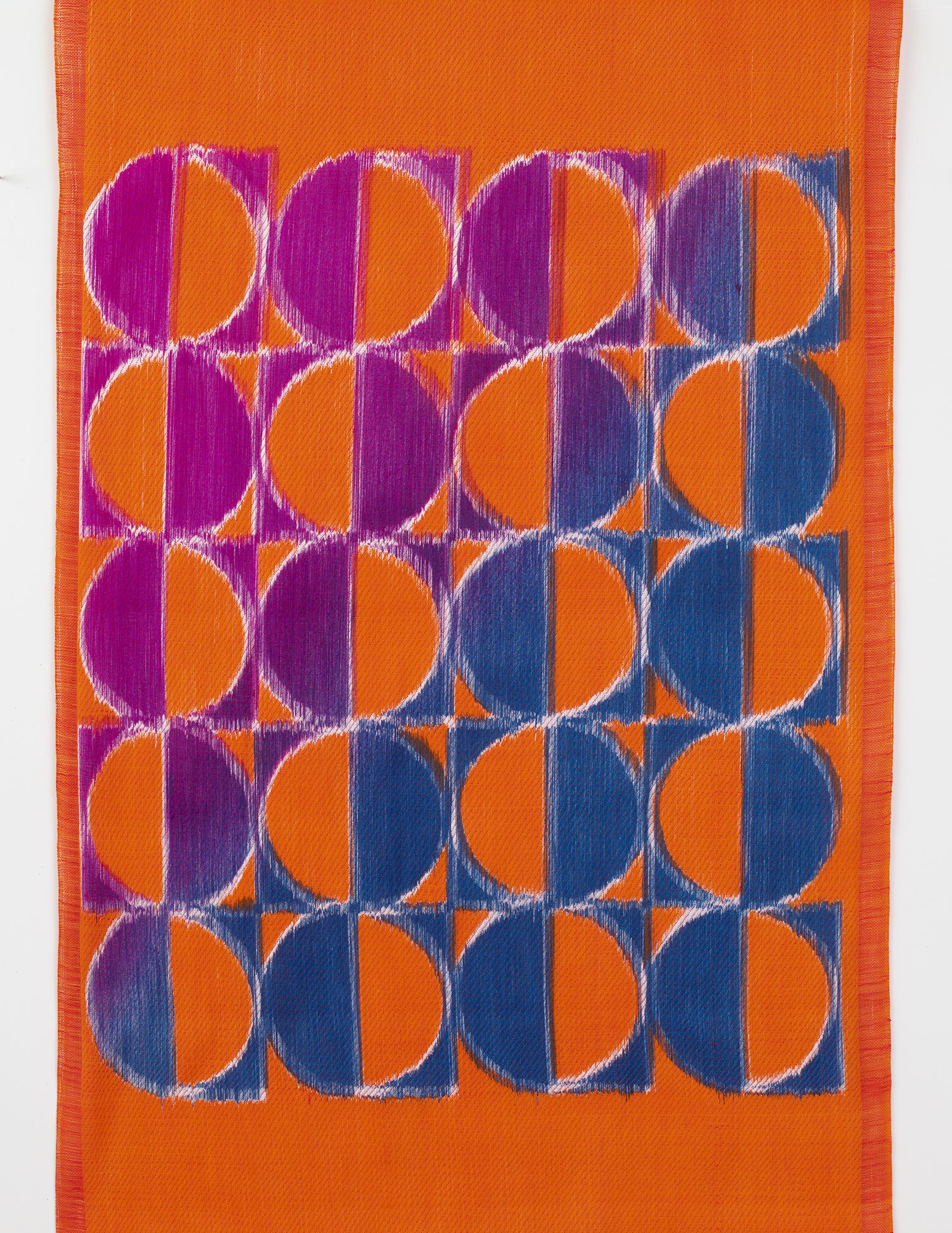

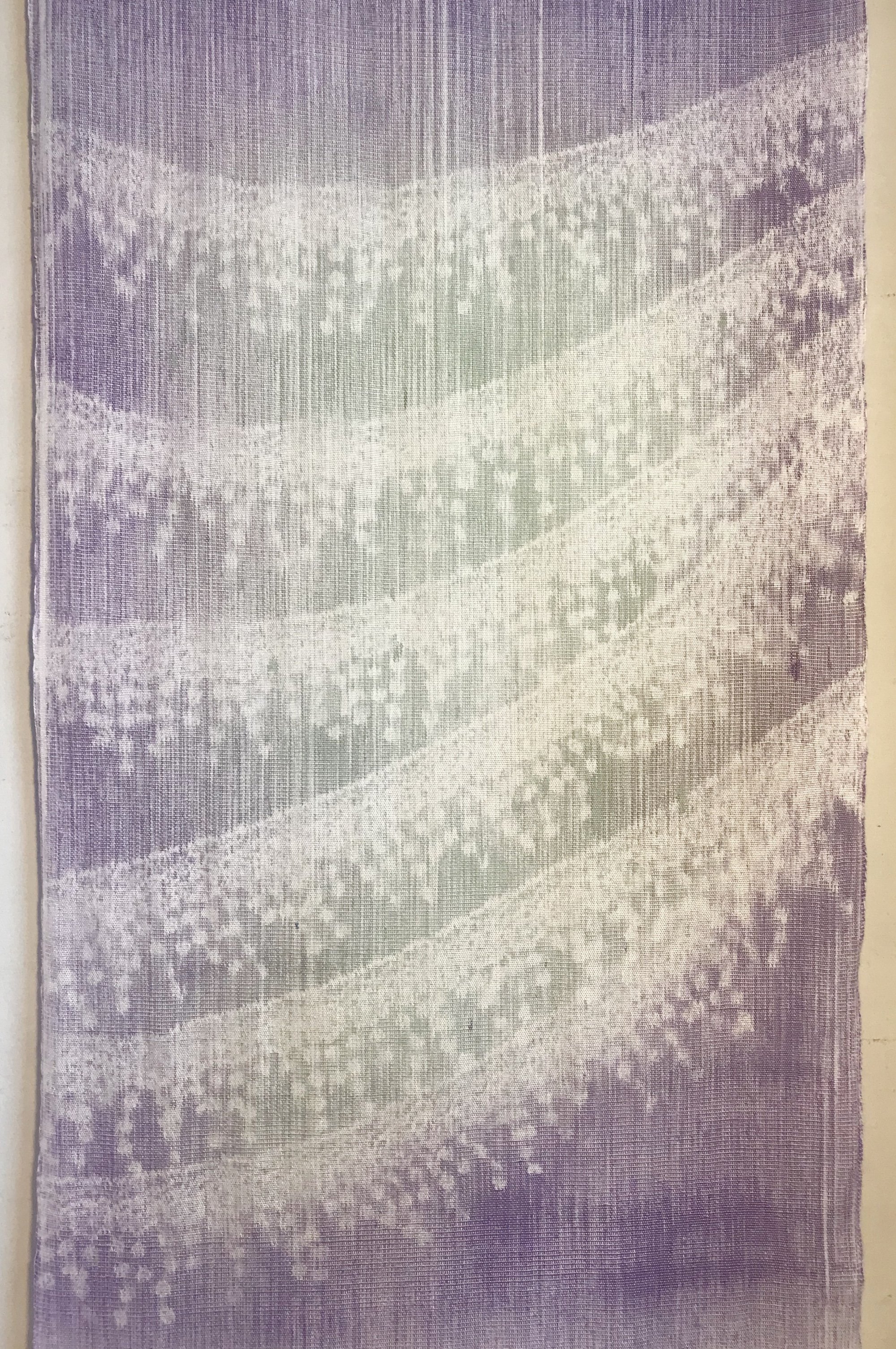

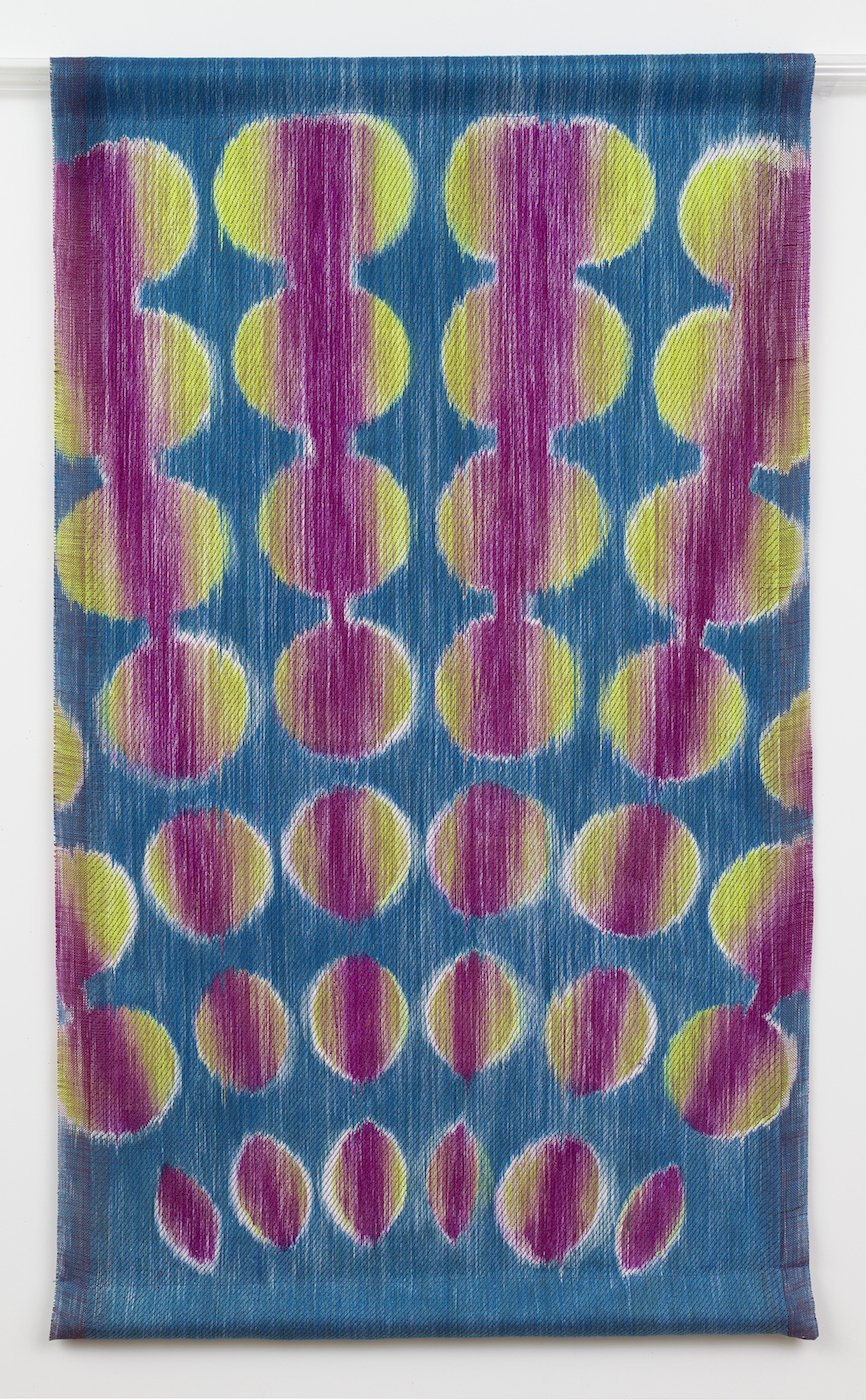

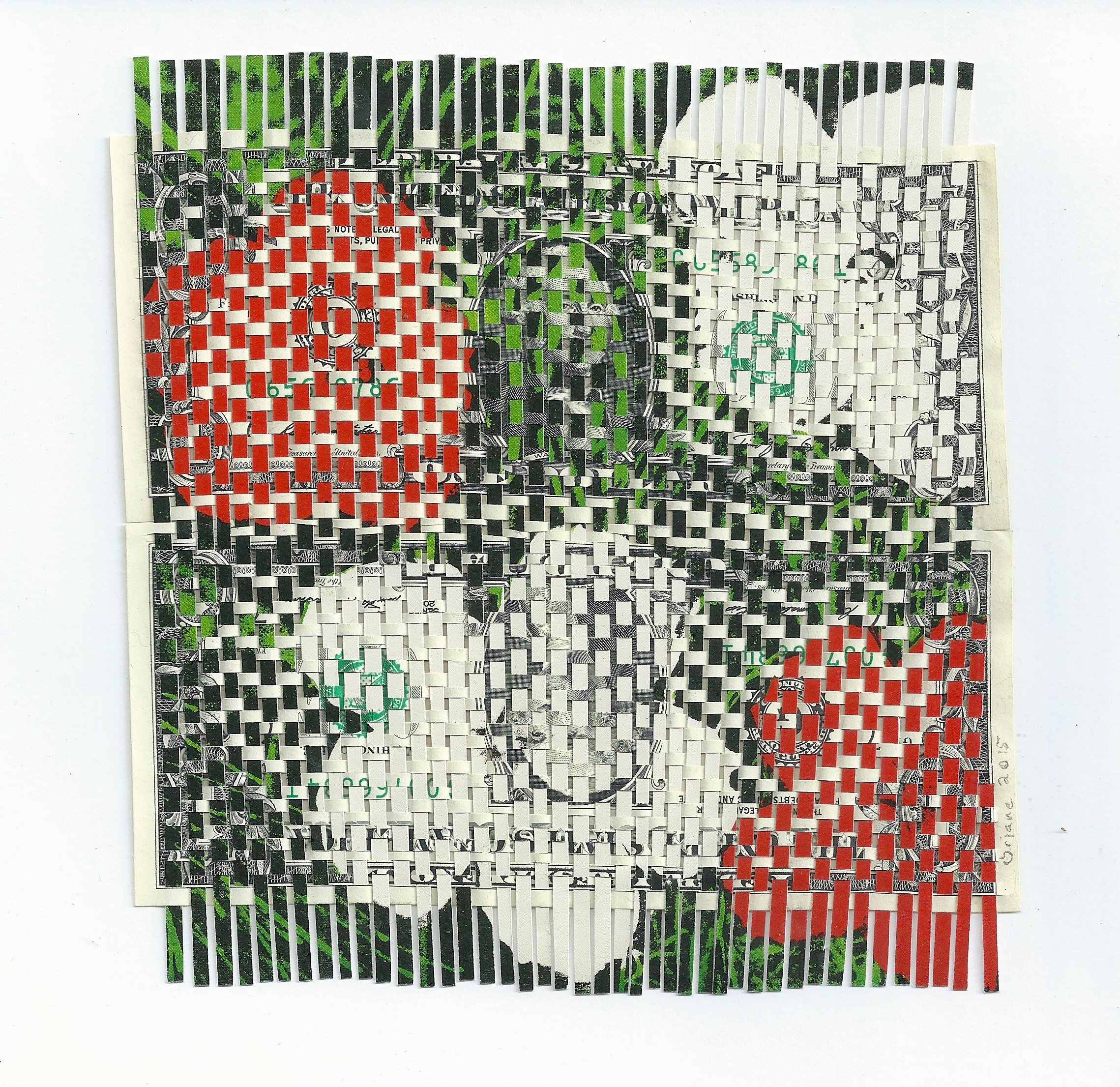

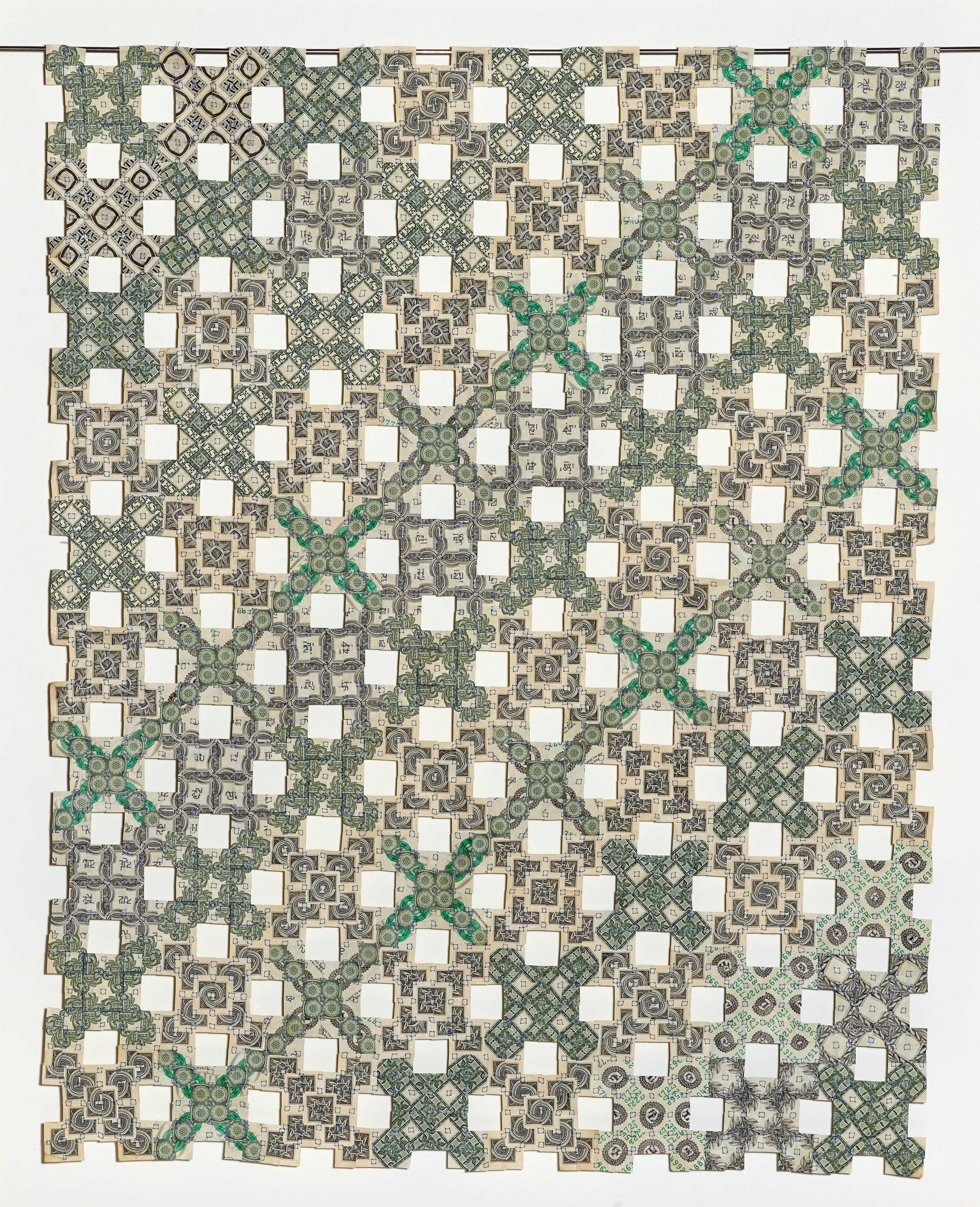

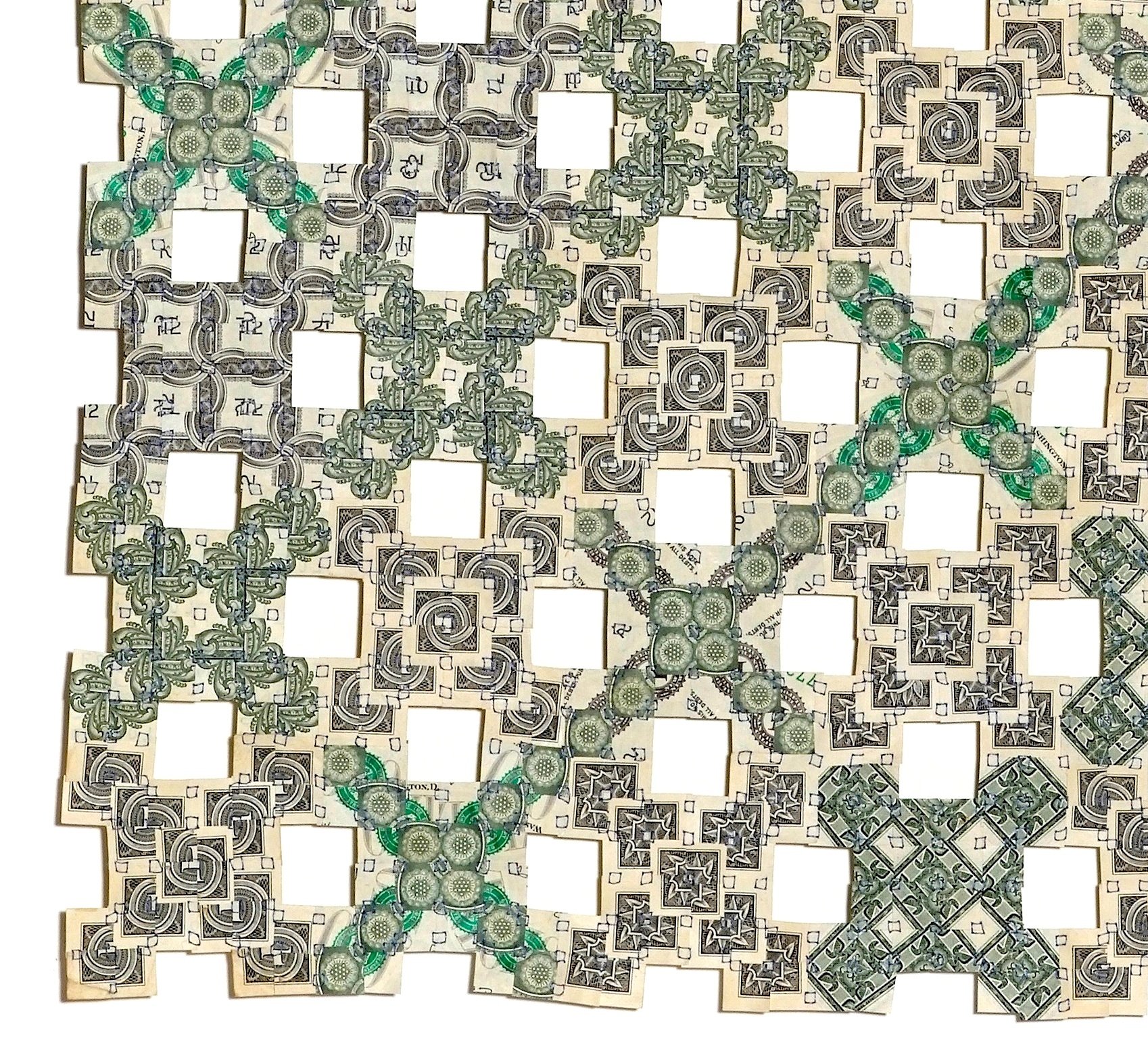

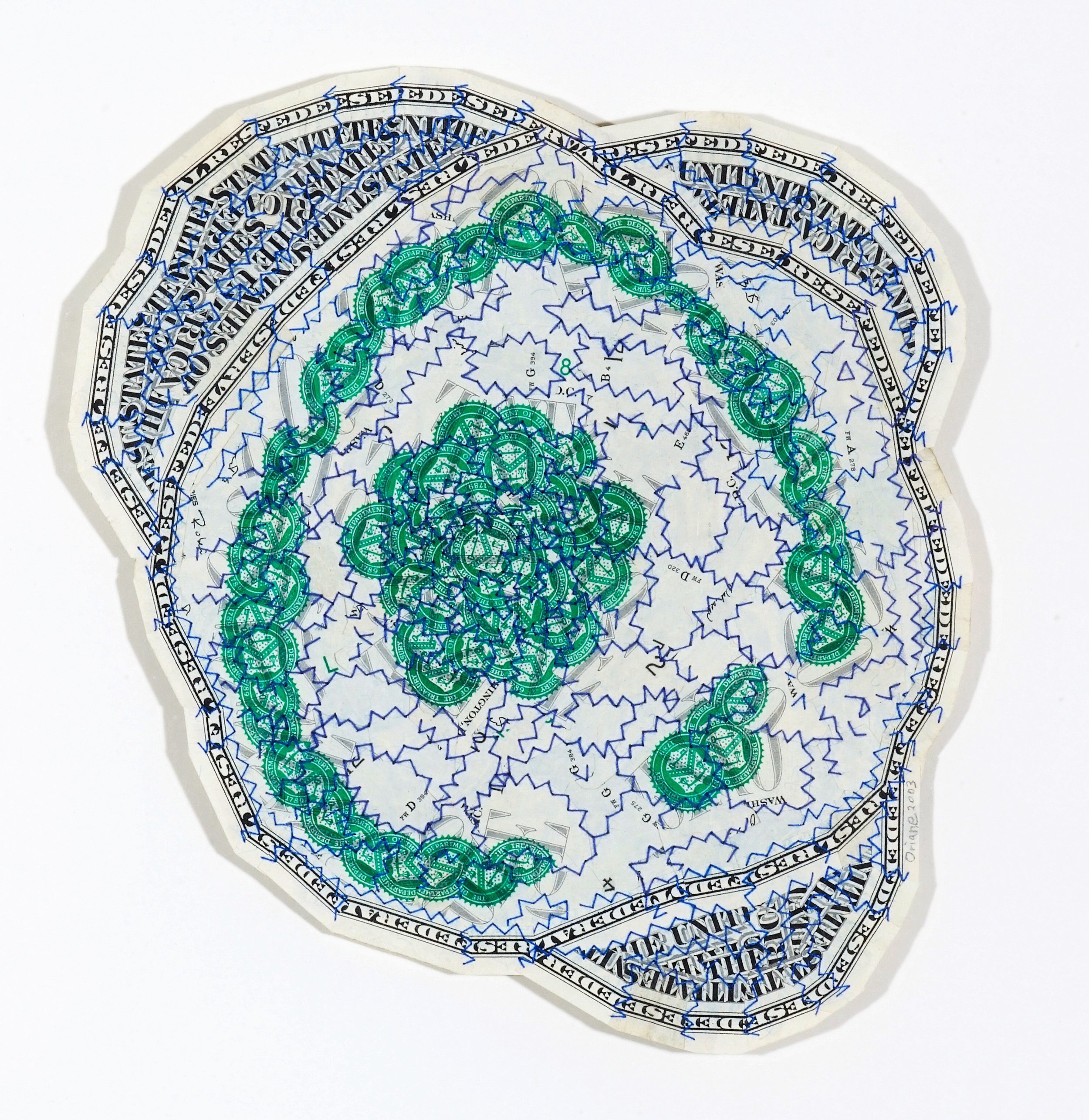

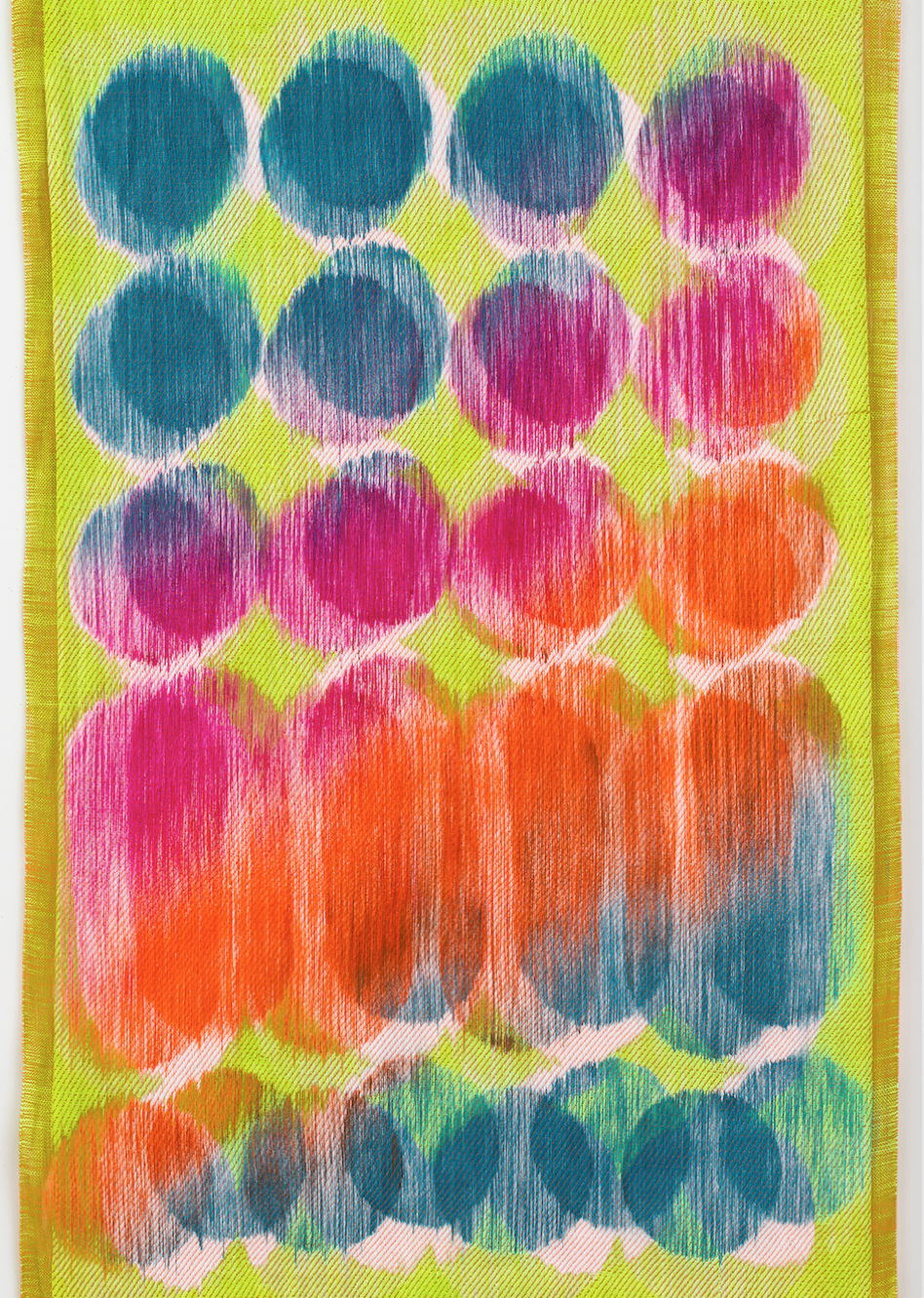

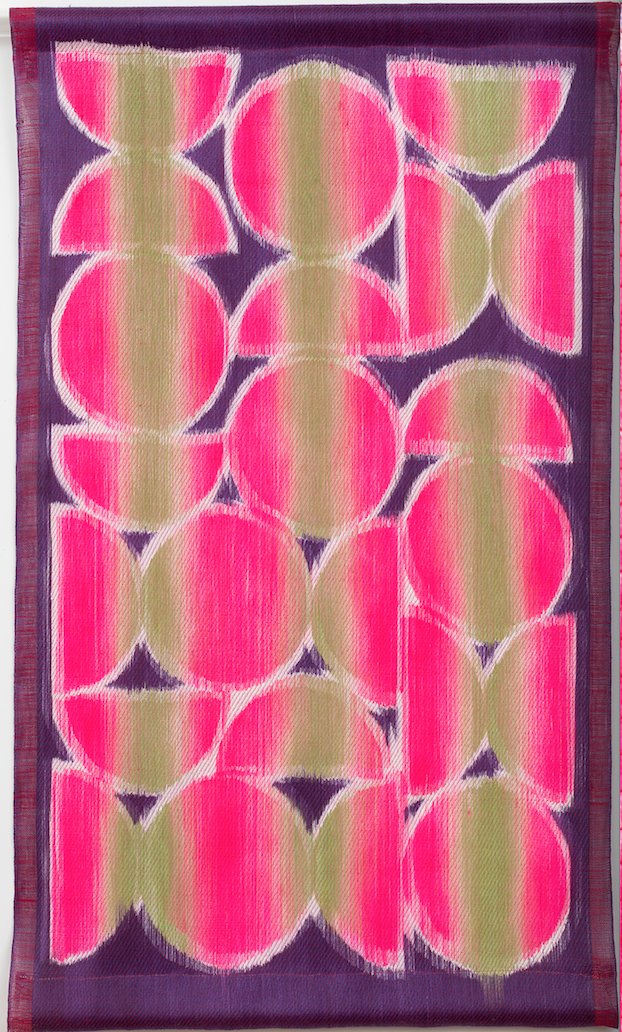

Oriane Stender is a Brooklyn-based artist who has worked with a variety of materials, from book pages to currency to stitched photographs. In her recent series, she combines traditional weaving with painting in a unique process that she has refined over time. These “woven paintings”, as she calls them, differ from conventional painting in that the paint is not applied onto the canvas, it is woven into it. The threads are painted on the loom ahead of the weaving process, resulting in a rich, variegated canvas with shapes that overlap, blur, and soften at their edges. Stender sometimes refers to herself in jest as a “soft-edge abstract painter”, a fitting description of her work on many levels. It’s fair to say that her larger body of work has always combined abstraction with some form of weaving, either literally or metaphorically. Her dollar bills interweave pop imagery with currency, a wry commentary on the consumer-driven art world, and her woven and shaped book pages carry a narrative of the parental expectations that cast a long shadow over her childhood. Over the years, Stender has seamlessly woven her identity into her work, rewriting her personal history and discovering herself in the warp and weft of her creative process. We covered a lot of ground in our conversation, but what came through was the grace and humor of an artist who is devoted to her practice, be it fine art, craft, or both.

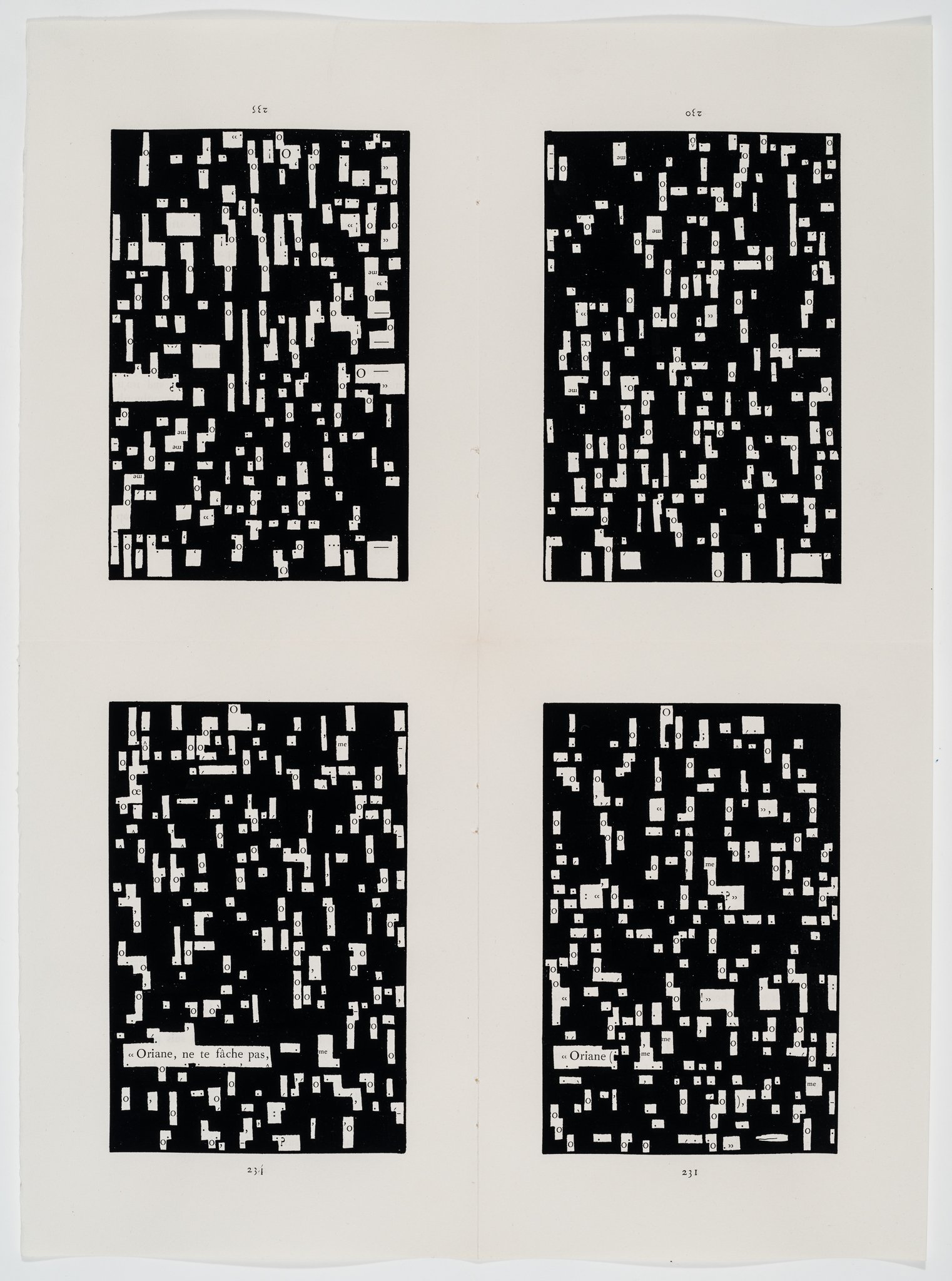

MH: For many years your work was paper based, much of it focused on currency. You cut, sewed, and wove dollar bills, and you also worked on book pages. Can you talk a little about your older series?

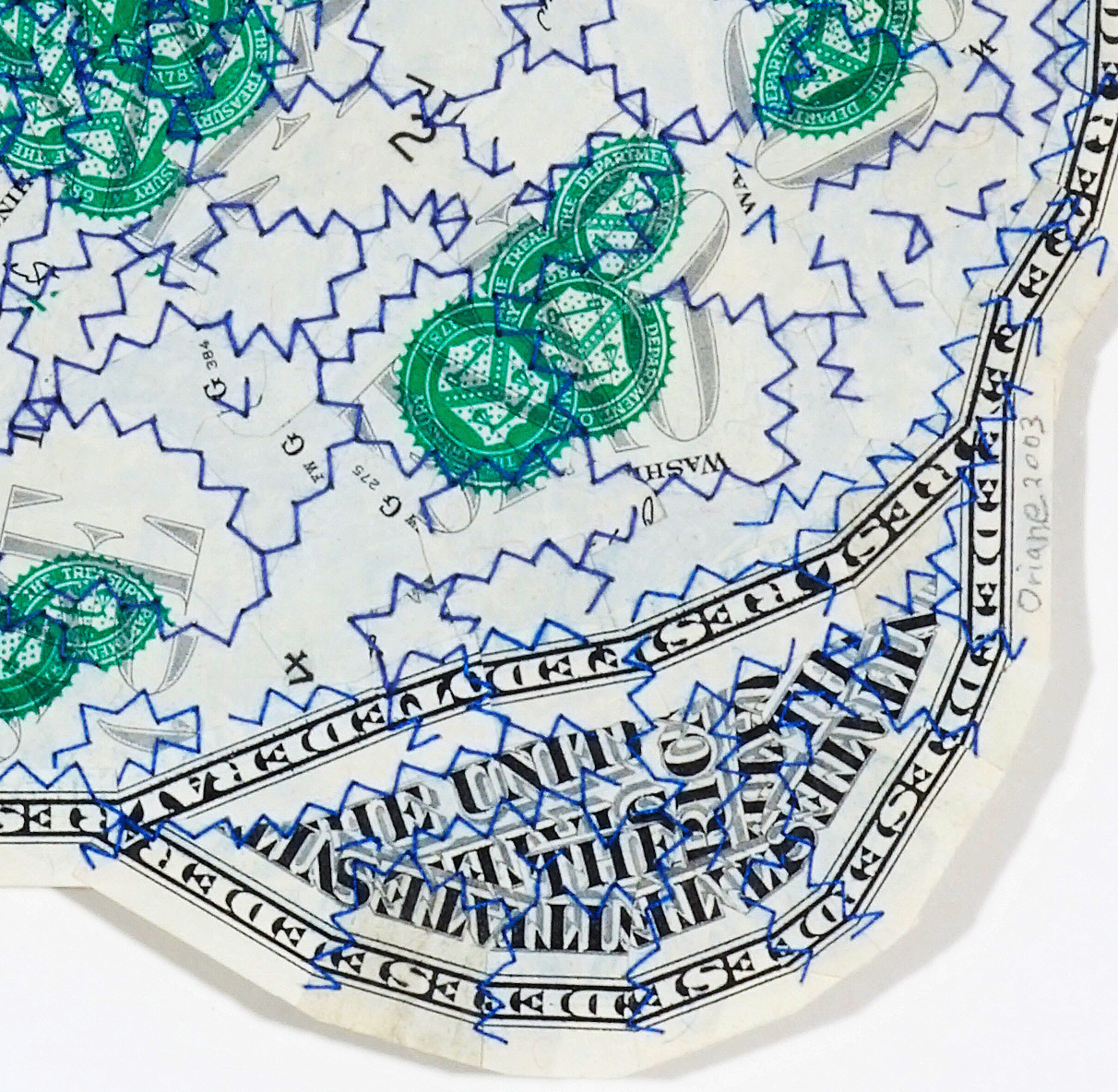

OS: I started working with money because it’s a material that everyone recognizes and has a relationship with. I wasn’t interested in the self-referential work that artists make when they refer to other artists and art history. The references don’t mean anything to someone outside of the art world, but money is something that everyone has feelings about, has a direct relationship with, and handles every day. And there’s a lot of imagery in the dollar bill that goes unseen, so I could zero in on all this imagery that was hidden, but in plain sight. It seemed like a fertile medium. The book pages were more personal. I’m named after a character from “In Search of Lost Time” by Proust, so I worked with pages taken from the novel. It was a heavy legacy, and I was never able to read all of Proust. I got through the first one but it was a slog, and a metaphor for heavy parental expectations. Like, they gave me this name and I can’t even read the book! So somehow by altering the pages, cutting and drawing and engaging with every page, I reclaimed my identity and made myself the protagonist of my own story. And as I worked, I listened to it on tape, so I did end up reading the whole book. This series was very personal and important to me.

MH: A few years ago, you made a big shift to traditional weaving. It seemed like a sea change, and I’m curious what instigated the shift in medium.

OS: I’ve always been interested in weaving. After I graduated from UC Berkeley, I took a semester-long weaving class at what used to be CCAC (California College of Arts and Crafts). I put a lot of time into it, bought a loom, and worked as a studio assistant for a weaver. What I like about weaving is that it has a strength and integrity as an art medium, because rather than making an armature and then painting on the surface, you’re building the structure and surface simultaneously as you weave.

MH: Were you dissatisfied with what you were doing before you moved to traditional weaving?

OS: It’s not so much that I was dissatisfied, it was more like I was done with that chapter. I might revisit it, and in fact I did a residency in France a few years ago and obviously I couldn’t take my loom, so I worked on my book pages. And I was making these weavings with paper, but I wanted to delve deeper into the practice that I was doing. Like painters who want to grind their own pigments, I wanted to get into the roots of the practice.

MH: You mentioned that your work is a hybrid of painting and weaving. How so?

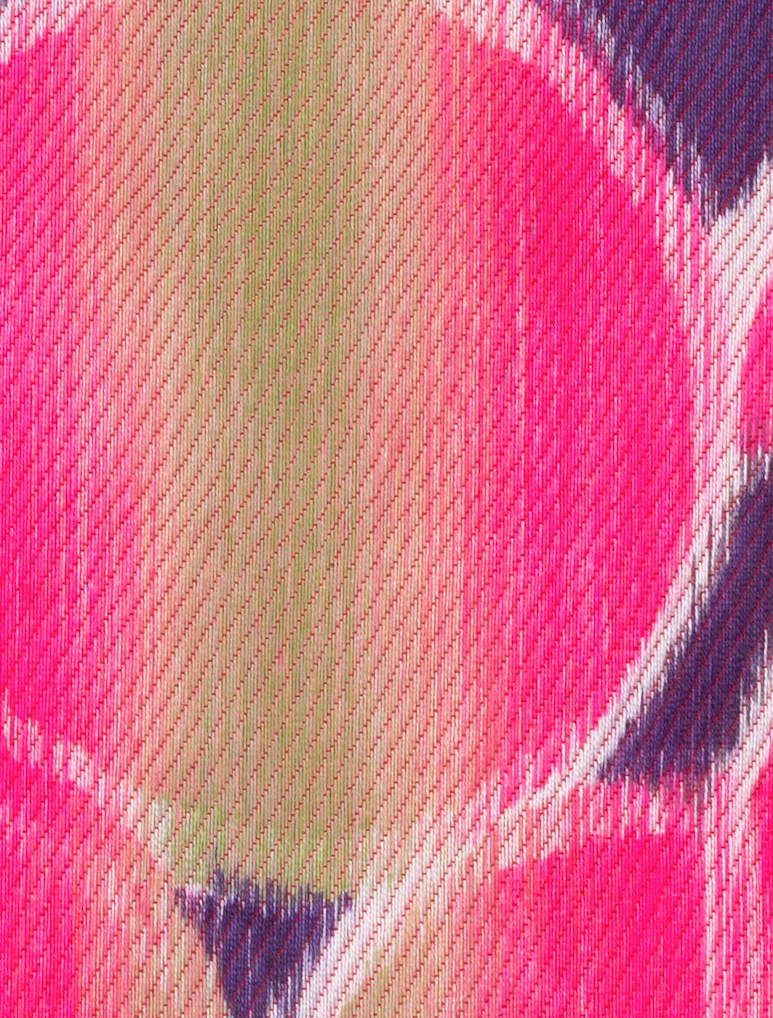

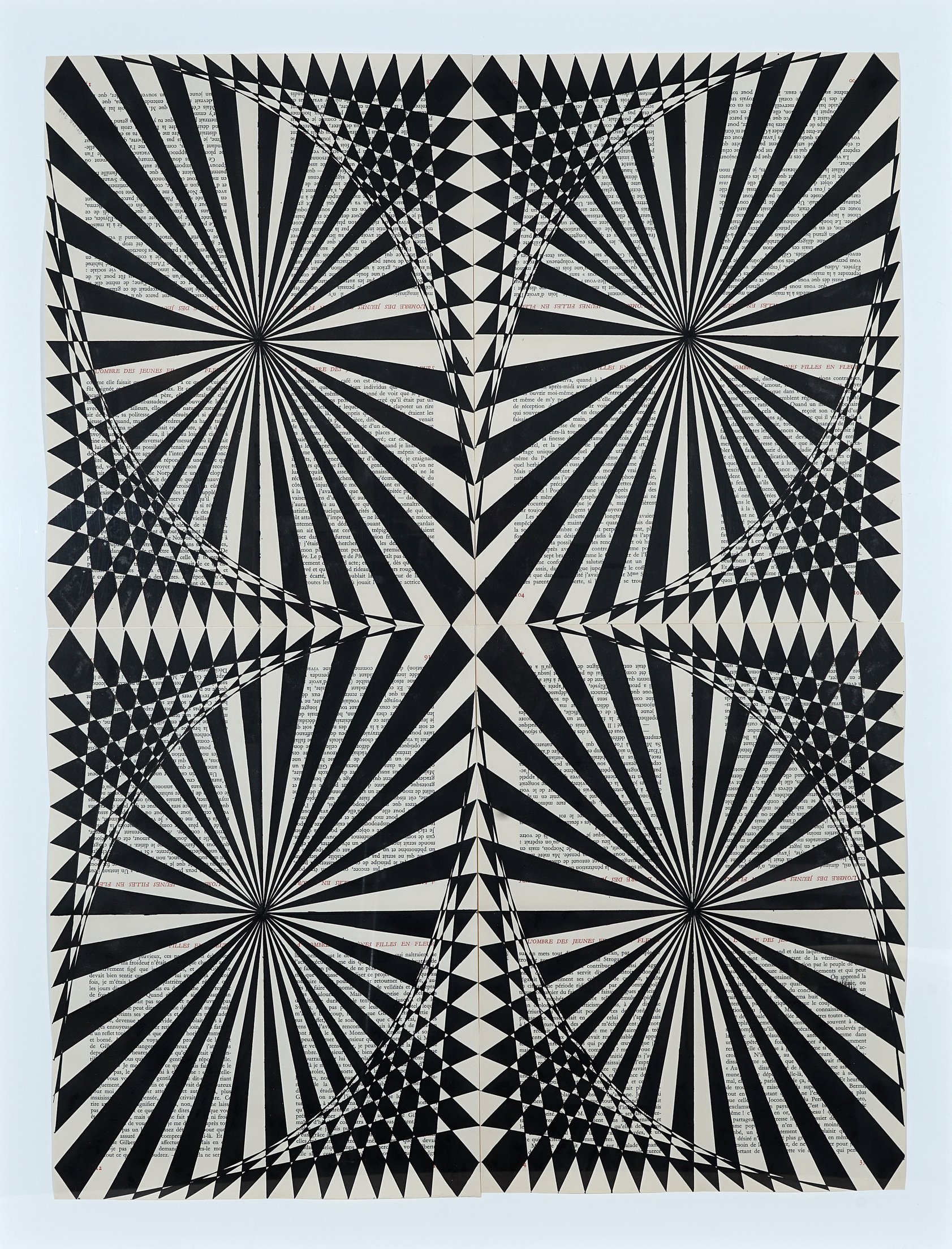

OS: In traditional painting you start with a woven piece of canvas and then you paint on the surface. I’m breaking that down and doing it in the reverse order. I paint the threads, and then I weave them into a solid canvas. I refer to them as “woven paintings”, and I’ve developed this process over several years, figuring out what kind of paint works best, how to pull the warp so it’s under tension when I paint, and which monotype and stencil methods work best. I’m not doing fancy weaving here – the painting is really where the action happens.

MH: What is the conceptual aspect of your work? How do you think about it?

OS: Weaving itself has a rich history. It’s an ancient technology that has contemporary applications, and there are mythologies around weaving from every culture. In most myths, women were the weavers, so that’s one connection. Another is the universal symbology of circles that I often use in my work. It could be the egg, fertility, the earth – I like to use imagery that’s not culturally specific. It’s not going to mean the same thing to everyone, but it’s going to mean something to everyone. And then there’s the metaphor of the warp and the weft. The warp is what’s set out there first on the loom, and it’s like the identity that my parents gave me. They had this child and they named it Oriane and it was their idea; that’s my warp. The weft is what you make of it. You can’t alter the warp once it’s on the loom, so it’s a metaphor for what life has set out for you before you do anything, and then the weft comes along and there’s all kinds of decisions that make us who we are. All these things come to me as I’m working; it's not like I think them up ahead of time. It’s a meditative process and I’m in this zone where I’m open to the metaphors associated with the task.

MH: Switching from a conceptually based, fine art medium to a traditional craft-based medium must have brought with it a host of considerations, some anticipated and some unexpected. Do you face any issues when you identify as a weaver? The art world loves to label, which can be annoying.

OS: I don’t see it as having left one world and entered another. I still consider it a conceptually based practice; it’s both conceptual and hands-on craft. But so were the money weavings. Even before I was working on the loom, it was important to me to have a good balance between the conceptual and the craft. If I had to distill the goal of my practice it would be to keep that balance close. Because it’s a dichotomy, like everything in life; you don’t want to fall too far on one side or the other. We’re whole beings, and we have to live both in our minds and in our bodies.

MH: Do you find that people react to you differently now that you’re a weaver?

OS: I don’t say I’m a weaver. I say that I’m working in a combination of weaving and painting. It’s not a practice that’s easily described. I sometimes call myself a soft-edge abstract painter, to distinguish myself from hard-edge abstraction.

MH: Craft was embraced by the snobby art world decades ago; in theory there’s no longer a delineation between “fine art” and “craft”. In your experience, has there been any residual snobbery? Do you ever feel that your work is regarded as something other than fine art?

OS: For sure, even though fine art is my background – I studied it and I know art history. I don’t have a background in craft so the assumptions that come with it are inaccurate. Some artists have broken down the barriers between art and craft, others haven’t been successful in doing so. I feel like it’s an unnecessary categorization, and I don’t concern myself with it too much.

MH: How or when does craft differ from fine art? One delineation might be that in traditional craft, the artisan disappears into the work and remains relatively anonymous, whereas in the fine arts, her presence is felt and pronounced. One is about the product, the other is about the artist. What do you think?

OS: I think the original division was that craft was about making useful things – all your plates, clothes, and the stuff that you use in daily life. When people got to the point where they had a little disposable income, they could afford to buy pretty things to put on the wall. That’s called “art” because it has no other function. But that’s a simple way of looking at it.

MH: Do you think the nonfunctional objects on the wall, or “art”, gradually became more about the artist than the art?

OS: Sure, it can be about status, like when a collector wants to buy a painting because the artist has a big name. When you get into the higher levels of art, collectors are buying a white painting because it’s a Ryman, not a white painting. That’s been around for a long time, with wealthy families like the Medici who commissioned portraits from the big artists of the day. But you could say that those paintings were also functional in the sense that they portrayed the rich person’s social status and helped them remain in power. And then there was the Church who paid artisans to create stained glass windows that told stories from the Bible for the illiterate people.

MH: It’s like fine art has an agenda, which may be political or religious, but craft has more of a utilitarian purpose. Fine art is trying to persuade you of something; craft has no axe to grind.

OS: Yes, but then you have to ask, what agenda does my art have? It isn’t didactic; it’s not narrative. Abstract work is different. Its agenda is more subtle, mystical, emotional, visceral – there are all kinds of reactions that it can evoke that aren’t just conceptual.

MH: Do you think that when craft crossed over into fine art over the last few decades, it lost its utilitarian purpose? I’m thinking of Ruth Asawa’s baskets that are not designed to hold anything. Maybe the definition of fine art is that it doesn’t do anything practical.

OS – And you can’t carry anything in it! (haha) You say that weaving has been accepted, but that’s not so universally true. There are some superstars that have made it into the canon – Anni Albers, Sheila Hicks, Sophie Taeuber-Arp – but it’s not like suddenly weaving was fine art. Some people have accepted it, and some haven’t.

MH: When an object is referred to as “well crafted”, it generally means that the hand of the artist is not seen. There’s an emphasis on the quality, integrity, and utilitarian aspect of the object. This is very different from the current art world, which values imperfection and even sloppiness. How do you approach your work now? Do you embrace the imperfections in your weavings, or do you prefer them to be flawless?

OS: I don’t pay any attention to what’s embraced by the art world. Trends come and go. In terms of my own work, I try for perfection, knowing that there will be plenty of mistakes, so I don’t have to program them in. I don’t have to try to make a drip because there will always be drips. I could try to control things more, but I let those things go and the imperfections are just there.

MH: In Japanese woodworking, the practitioner is taught the skill of complex joinery over many years of apprenticeship. The focus is on the integrity of the lineage, and self-expression is not valued in the tradition. Do you feel connected to a lineage of weavers, across history and cultures?

OS: Yes, but in more of a broad sense. I haven’t studied under a strict lineage, so I don’t have that connection, but I feel connected to the history of weaving. At this point we’re so disconnected from the earth’s history and human history that it’s like we’re on some alternate planet. We sit in front of screens, we don’t grow our own food, we don’t do the things that people used to have to do to survive. Any feeling we have of connection is more on an intellectual level. Weaving is something I do that links me to the past in a positive way.

MH: When you’re working in the studio and at your very best, do you ever “disappear” into your work? Is there ever the sense of merging with your medium?

OS: Not so much merging with my medium, but there are times when I’ll forget to eat, or suddenly I realize that I’m faint because I haven’t stopped for hours. But yes, there are times when I’m really in the flow, and it feels like the weaving has a direction and I’m just following it.

MH: These rarified moments in the studio of becoming one with the medium are what the mystic strives for. It’s like we transcend the dense material and rote process and experience an extended moment of bliss. Does this happen because we lose our sense of separateness?

OS: I don’t feel like I disappear. That feeling you’re describing I get that more from yoga. I get that in moments in weaving, but not for extended periods. There are so many tasks involved with weaving at the loom that it would be hard to lose myself completely.

MH: The mystic refers to these moments of bliss as “a glimpse of the goal”. Beyond the galleries, sales, and reviews, what is your ultimate goal as an artist? Have you had glimpses of it?

OS: On one level, I feel like what we do as artists is very selfish. We’re not out there saving the world, feeding the poor, whatever. We’re here trying to make things that please us and give us a transcendent feeling. But how much of that is just to make myself feel good? So you can look at it as totally selfish, but it’s also possible that my work will inspire someone, or give them a feeling of transcendence. For me it comes from a place of self-care and self-healing, and I don’t know if I need to know what the greater goal is. I continue my work with this sense of devotion without knowing whether it’ll mean anything to anyone else.

MH: Devotion to what?

OS: Hard to say, because I don’t have any spiritual beliefs. It’s a discipline. I don’t have much discipline in other areas of my life – this is the only one, so without it I’d just be a blob. I don’t know what motivates me to work with so much devotion, but it’s very healing for me.

MH: I wonder if your work carries the essence of self-healing in some way. If an artist makes work that has a certain energy or intention, does it show up in the work?

OS: Hopefully the objects that you make will carry some of that spirit and affect someone else. That would be great. I can’t say that’s my goal, but I think it’s a possibility.

MH: Are there any last words that you’d like to say about your work and your process? Something that might be generally overlooked by your viewers?

OS: Explaining my work and making sure that people understand it was more important to me when I was younger. Now I feel like if it takes that much verbiage to get you interested, then it’s not doing its job visually. I hope that the work is successful from a distance and then as you get up close it reveals something more. I think if they look closely, they’ll see that there’s a lot going on.