Carla Rae Johnson is an artist, writer, educator, feminist, and social activist. Her work is about individuals and collaborations, some historic and some imagined, often addressing inequality and social injustice. In her current show at Garrison Art Center, From the Séance Series, Johnson brings together historical figures from disparate periods to engage in intimate tête-à-têtes. She creates sculptural tableaux where these unlikely couplings take place, with accompanying drawings, and the viewer is left to imagine the dialogue between the players. No two people will hear the same conversation: some will hear Audre Lorde praising Abraham Lincoln for his courage in abolishing slavery; others will hear her chiding him for not taking a harder stand against the South. The brilliance of Johnson’s work is that she gives you the information – and she does copious amounts of research for every tableau – and then she backs off and lets your imagination fill in the blanks. Her larger body of work includes painting, drawing, sculpture, performance, installation, and a fair amount of humor. Indeed, she uses her sharp wit and a seemingly endless supply of puns to address difficult issues of social and political import. Running through all Johnson’s work is a golden thread of compassion for her fellow travelers, a faith in humanity that supersedes the current movement toward intolerance. As racist and patriarchal belief systems attempt to elbow their way back into the mainstream, it’s encouraging to encounter an artist and activist whose work is deeply rooted in justice for all.

***

My conversation with Carla Rae Johnson was a live event, recorded at Garrison Art Center in Garrison, New York on May 28, 2022. The following is an edited version of our conversation.

***

MH: The Séance Series proposes hypothetical meetings between creative and historic figures who never met during their lifetimes. How do you come up with the pairings? What questions do you ask of them, as the facilitator of the conversation?

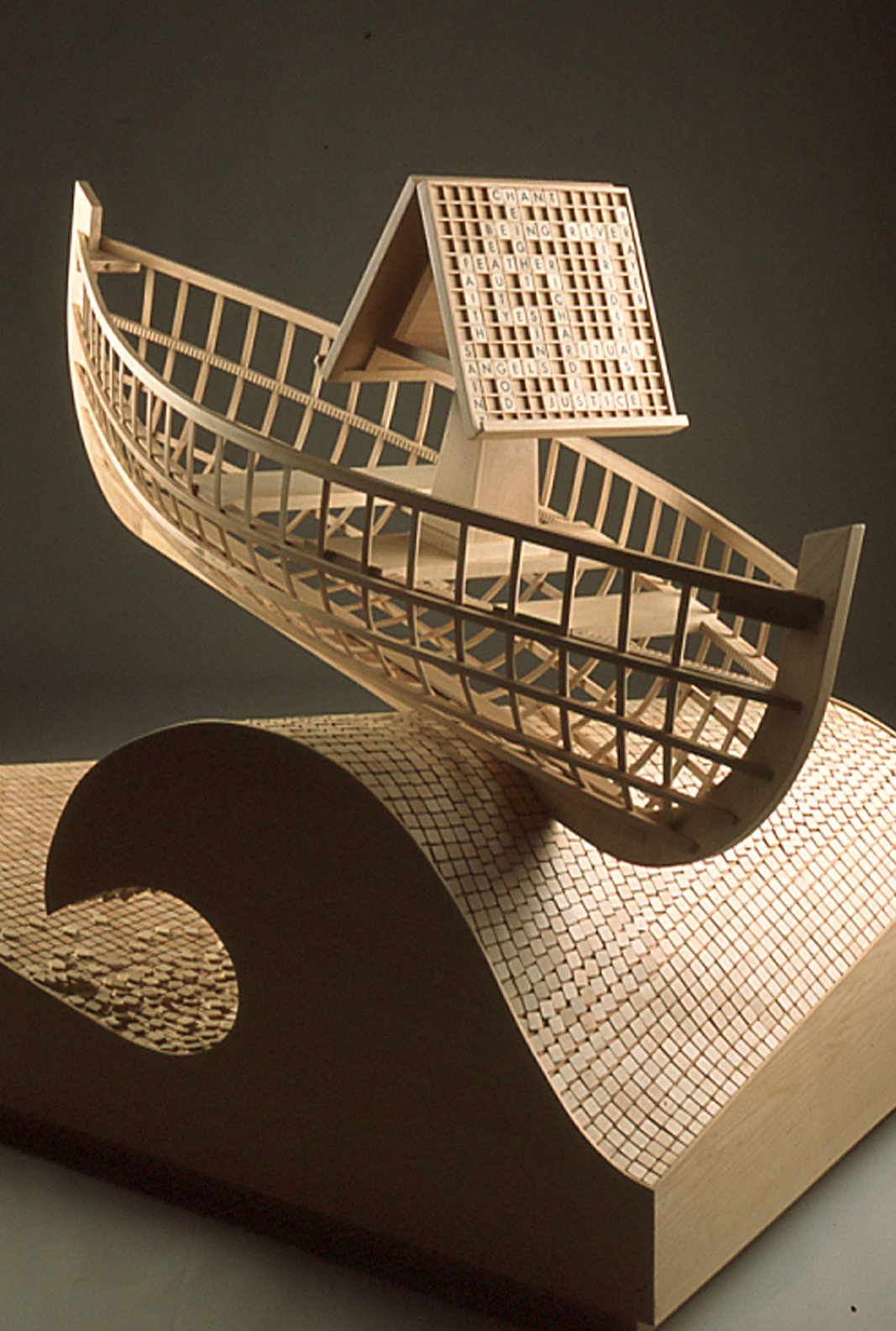

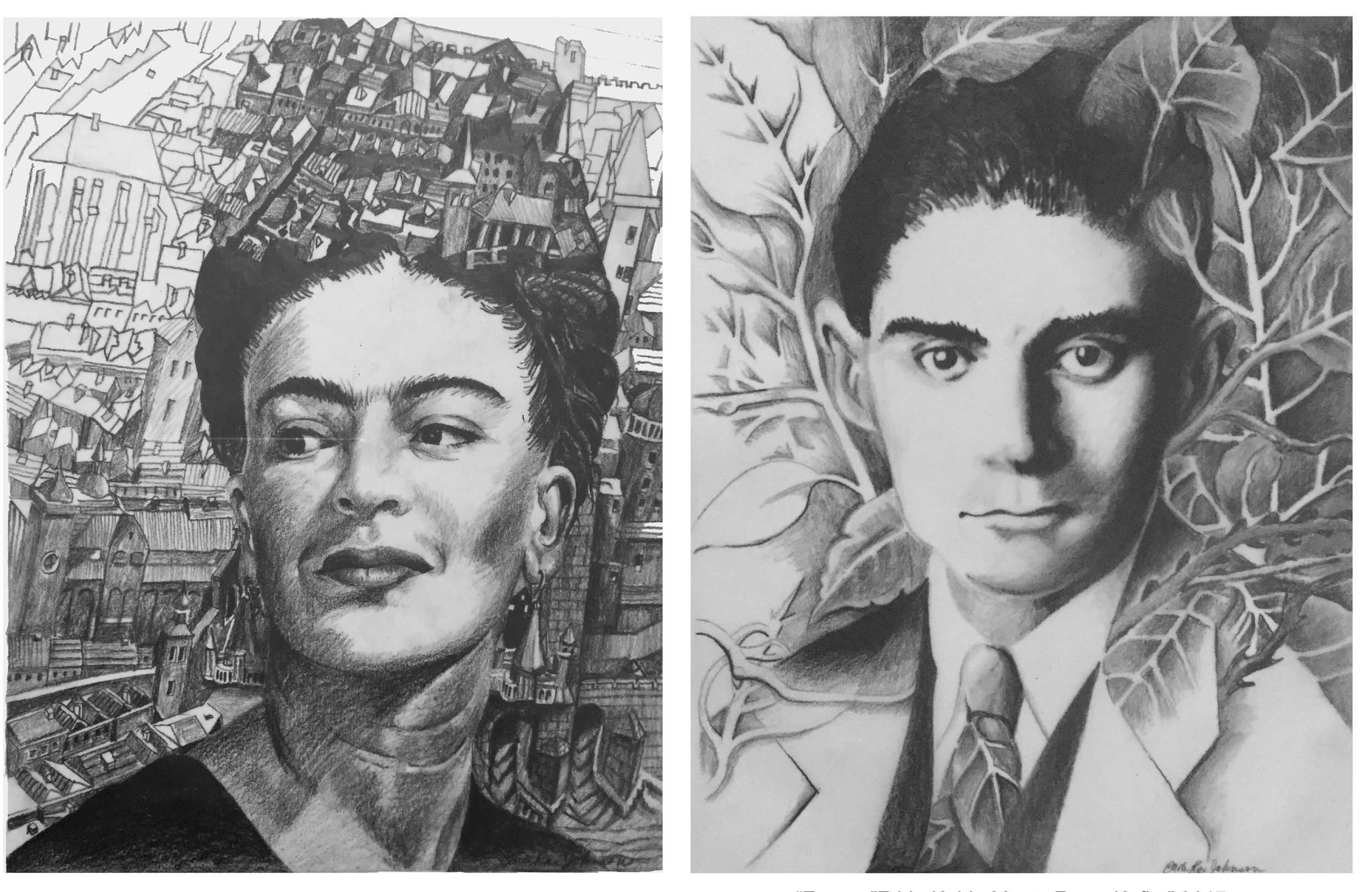

CRJ: When coming up with the pairings, I try to choose opposites – people who you couldn’t imagine talking to each other, or even in a room together. They’re usually figures who are separated in time, although some of their lives overlap chronologically. I only consider people whom I’ve admired at some point in my life, people I think very highly of. I research each person for at least a year, reading anything I can get my hands on that they wrote or said, including their biographies. And I bring them together through drawings, which are usually done first. I find visual metaphors that connect the two figures, and I find common ground in terms of what they said or did or who they were. Then I create a visual tableau that’s like a theater set: it’s the furniture for their meeting. Instead of asking them questions, I posit that they’re playing a game with each other. Games are a form of communication, every bit as potent as a conversation, and choosing the game and how it’s played also informs the piece and how the two come together.

MH: I was especially drawn to the piece “Audre Lorde Meets Abraham Lincoln,” which is included in the show. One of Lorde’s famous quotes is, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house”. This would have been very challenging for a white privileged patriarch such as Lincoln. Do you consider the discomfort and disparity that the pairings create?

CRJ: Yes, there’s a little feminist agenda there. I do think that Audre Lorde would have held Abraham Lincoln to task. She was a 20th-century activist and described herself as a black lesbian feminist warrior poet mother. She and Lincoln are playing bridge, but it’s not the card game; it’s an actual bridge, and I felt that Lincoln is the one who has to build it. He’s not at all finished, because as you can see on Lorde’s side, it’s incomplete. Today more than ever we can see how incomplete it is and how much work needs to be done.

MH: I think it’s brilliant that you incorporate some Lincoln Logs into the piece. Your work is often humorous, which is interesting, given that your subject matter can be heavy or controversial.

CRJ: Humor is a thread that has run through the work from the very beginning. I grew up with humor in my household; my father was an inveterate punster. I use puns unreservedly in my work because I find them to be concise metaphors. They put two ideas together in one word. So even though everyone moans and groans when there’s a pun in the house, they’re very clever and can sometimes be profound. And yes, those are intended to be Lincoln Logs.

MH: It’s very subtle.

CRJ: Yes. Another thing that I love about incorporating humor is that it’s a way to say hard truths. You package them in such a way that people smile, and then they process after the fact. If they have no entry point to a challenging idea and it’s simply didactic, it’s less likely that they’re going to try to process the information or the truth that’s there. So humor is a way to do that for me.

MH: I love the idea of these conversations happening between artists from different eras, or “time zones”, as it were. Have you thought about whom you’d like to be paired with? What would you talk about?

CRJ: I’d like to sit down with Fanny Lou Hamer. She was a Mississippi sharecropper in the 1960s, and her parents had twenty children. She came from a dirt-poor situation, had a sixth-grade education, and lived at the height of racism and horror in rural Mississippi. She fought for voting rights, not just for black people but for women, the less educated, and all people. Some civil rights leaders wouldn’t listen to anyone who wasn’t Ivy League-educated, or who didn’t have a Ph.D., but she encouraged everyone to come to the table. The reason I’d like to talk to Fannie Lou Hamer is that she was never intimidated, even though she was beaten and her life was threatened. I want to know how she kept her positive attitude and her hope in the face of what was going on in Mississippi in the 1960s.

MH: I’ve heard some people say that they don’t like descriptive titles. They say that they get in the way, but I think they’re saying that the concept is getting in the way of experiencing the piece on a purely aesthetic level. Where do you stand on this? How important are the title and conceptual aspects of your work? Is the piece complete without them?

CRJ: Extremely important, and no, it’s not complete without it. If there were no words or descriptions in the gallery, it would be very challenging to identify the figures who are represented here. I came up through art school in an era when you weren’t supposed to talk about the work, ever. If it needed verbal buttressing, it wasn’t up to snuff. And if you went to hear a panel of artists, it would be all guys, and they wouldn’t speak about the work – it was supposed to speak for itself. I never bought into any of that. The work comes from a conceptual base, and I want people to understand it. I’m aware that an artist can make work that gives you all the information you need to understand it, and you say, okay, I get it, and walk away from it. You can also make art that’s open, with a wide variation as to how that piece could be interpreted. I think I’m in the middle somewhere because I don’t want it to be wide open, although every time I talk to someone there are some new insights, so it isn’t completely closed off.

MH: If someone came to the show, looked at the work, but didn’t read anything, is that ok with you? If they like a piece and respond to it but don’t know what it’s about?

CRJ: Oh hell no, I’d grab them by the collar and pull them back in. [haha] Of course I’d be open to that. My intention is that these will be beautiful, elegant objects to contemplate whether you know what I intended or not. But you might get a sense of an unfinished task here, a sense of imbalance and discomfort there, or you might pick up on some inequality going on. Those things might not be verbal, but I would hope that those sensibilities would come into play.

MH: Do you enjoy the process of making the work as much as coming up with the ideas? I’m wondering where you geek out the most in your process – is it in the craft, or in solving the technical issues that come up when you’re working? Or do you go down rabbit holes with your ideas?

CRJ: Sometimes I hate the process, like with one piece in the show there were a lot of compound angles, and I didn’t know how to cut them. I’m self-trained as a woodworker, so there's a tremendous amount of head-scratching that goes into it. That part of the process is a lot of fun once you figure it out. It’s very empowering. But I think the more fun part for me is the conceptual end of it: dreaming up the idea, tossing it around, doing the research, and I have a lot of fun doing the drawings because they’re another way of discovering the piece.

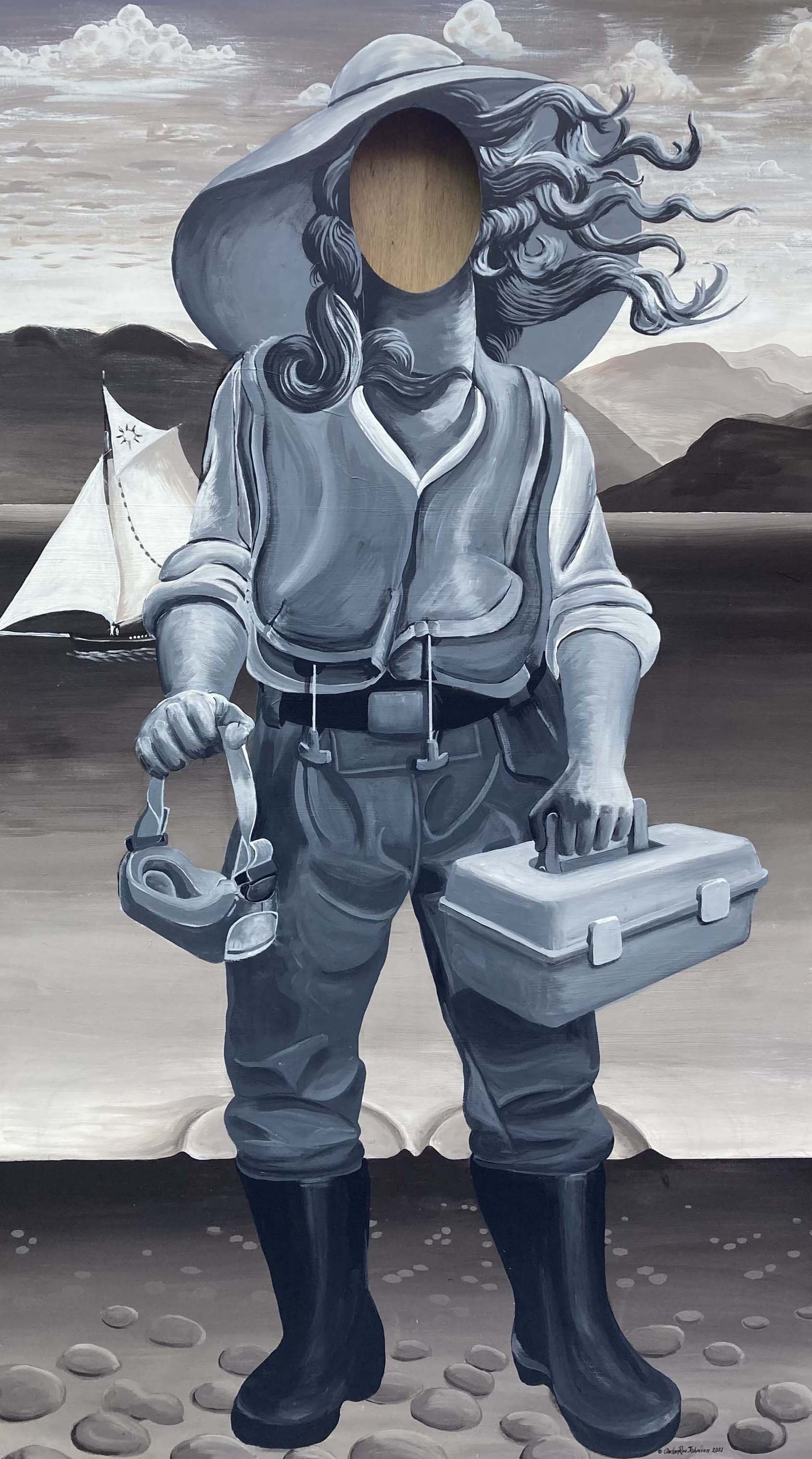

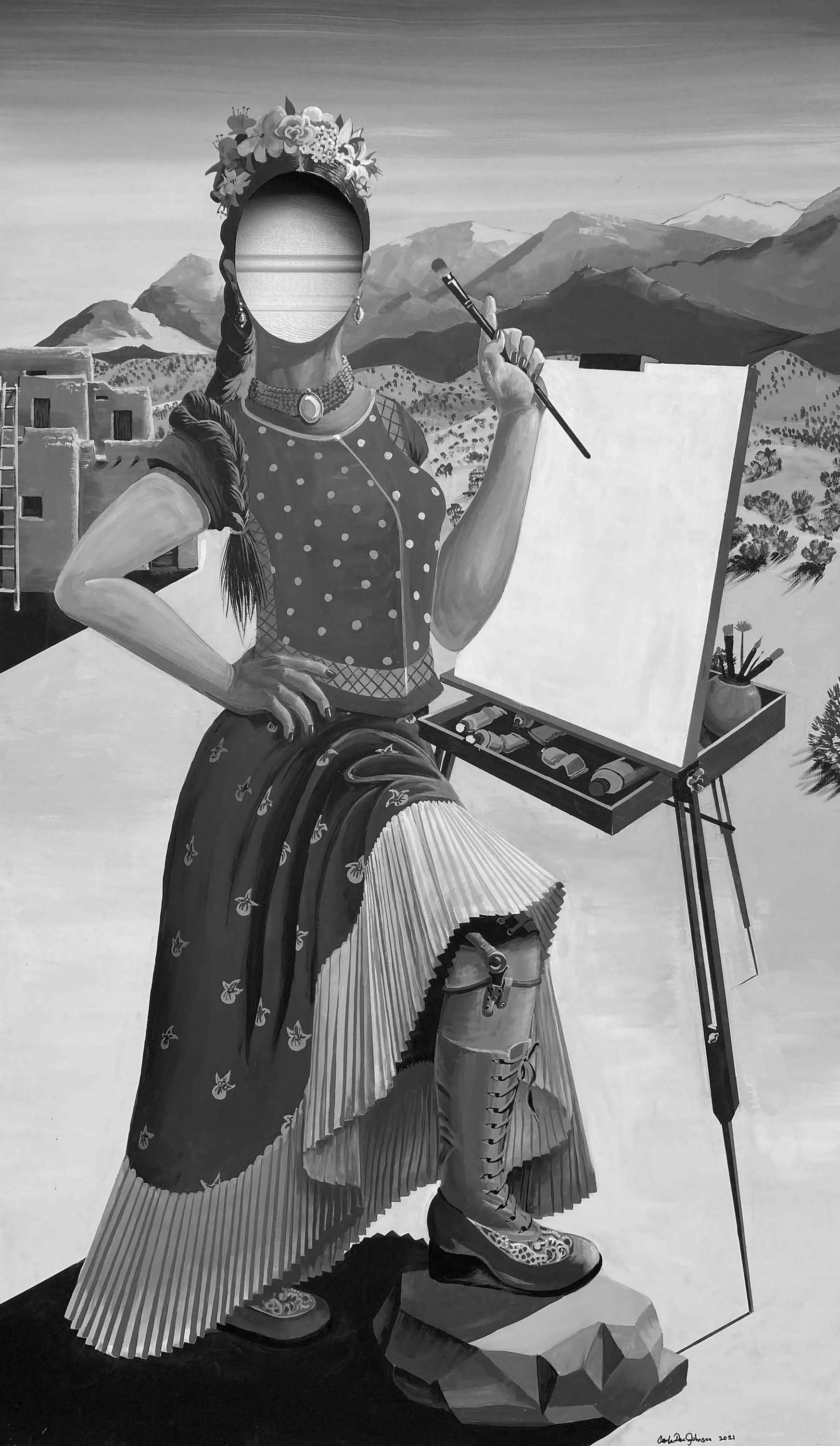

MH: A recent body of your work features larger-than-life female figures painted on panels with their faces cut out. Visitors can stick their heads in the hole and have their photo taken as an imagined historic figure. The viewer becomes Virginia Woolf as an environmentalist cleaning up the Hudson River, or Harriet Tubman, helping those seeking asylum at the U.S. border. It feels like you’re psychologically putting the viewers in other people’s shoes. In one piece, you literally place the viewer on a pedestal. Beyond the fun photo ops that these pieces generate, do you think that your interactive works evoke something in the viewer, some sensibility to these women’s causes?

CRJ: I have no way of knowing. I’ve never had anybody who put their face in a hole and had their picture taken come up to me and say, “Oh my God! I’m Virginia Woolf!” But yes, the intention is to evoke a sensibility for these women. I wanted people to think like Virginia Woolf, or have the courage of Fannie Lou Hamer, and what I realized is that all this artwork that I’m doing, bringing people back, is because I notice something missing in myself. I’m not a courageous person, so I figure that if I keep making art about Audre Lorde, maybe I’ll be more courageous, and maybe my voice will speak out at a moment when it really matters. The only way we can bring these women back is to become more like them ourselves.

MH: When I look at your larger body of work, I see a theme running through it that can be summed up in one word: compassion. Your work is about individuals and collaborations, some historical and some imagined, but always with the intention of creating equality for all human beings. Where does this drive come from?

CRJ: That’s the first time I’ve had the word compassion used as a description of the thread that goes through the body of work. It’s been a long process for me to move toward work that is focused on social justice. But certainly, social justice is compassion. This drive may have come from my Methodist upbringing, but I think where it really comes from is the Holocaust. When I was in college, I took a course in 20th-century American history, and the teacher showed a film called “The Twisted Cross”, which was a propaganda film that had women and men falling all over themselves to get close to Hitler. I’d never thought the Holocaust was a real thing that happened until I studied it and understood the events leading up to it. It devastated me, and I knew that I needed to do something in my life that countered what happened there. I didn’t know how or what, but I was thinking about being an artist, and I pursued that path because nobody told me otherwise. So I think that was the germ of how this all came about.

MH: If you stand in front of a work of art for long enough, you get a sense of the artist’s creative process: her mistakes, her frustrations, and how she pulled it together. What emerges is the intelligence of the artist and the expression of immense compassion. Does this ring true for you? Do you think that art conveys the humanity of the artist?

CRJ: I think it can. I’ve known some artists who made some deeply sensitive work but were real assholes in their lifetimes. I personally respond to art that conveys that compassion.

MH: Is there an artist who comes to mind whose work evokes compassion?

CRJ: Kate Kollwitz’s works evoke that for me, probably Mary Cassatt, although I’m not a big fan of Impressionism because of the eye candy factor, but there’s a lot of mothering compassion that comes through in her work. I also think the work of Goya shows compassion.

MH: I thought of Rothko.

CRJ: Yes, and Sue Coe is a contemporary artist whose work is in your face with the kind of imagery that’s built on compassion for animals and humans.

MH: In some ways, art is a salve that provides the artist with some relief, and then we share that with others, hoping that it will give them some relief as well. What do you think of that idea?

CRJ: I think that’s true, and that’s at the heart of what I’m trying to do.

MH: I once read that the history of art is the history of artists. It’s easy to forget when you’re wandering through the Met, or leafing through Janson’s History of Art, that each painting, each sculpture is evidence of a life that was concerned with experiencing and expressing what it means to be human. And every artist does this in her own way. For you, it seems that the way to be human and to be an artist is to address issues of inequality and injustice.

CRJ: Yes, I think that’s true, but not always. A couple of the Séance Series pieces weren’t so much focused on social justice as on the creative process. Duchamp and Dickinson were two creative people who were groundbreakers during their lifetimes. And the pairing of Beethoven with Bessie Smith was about joy and fun, although she also sang the blues.

MH: To quote the sculptor Stephen de Staebler: “Behind every artwork, there is a breathing, feeling human being called ‘the artist’ who creates out of a drive and an energy that remains untapped in most of us.” What is ultimately more important, the life lived, or the artwork produced by that life?

CRJ: The life lived, without hesitation. Artists are always going to make beautiful and meaningful things, but there’s no way to replace the complexity of human life with all its experiences, and how that life interacts and interrelates. I was a teacher for almost forty years, mostly college art classes, and it occurred to me toward the end that all the energy and creative thought that went into the classroom studio was every bit as important to me as making art. I was totally absorbed in teaching, because it’s direct, while art is indirect. In the classroom, people get inspired, and they inspire each other and it's so exciting to watch people become empowered.

MH: I think of some of the tortured souls who were artists, many of whom died young. I’m thinking of Van Gogh, for example, or Beethoven. Was it their suffering that made the work great? As tragic as it was, I feel like it was their suffering and humanity that connects us to the work and makes it so rich.

CRJ: I think that’s true. When I was in my teens and twenties, I thought I wouldn’t live beyond thirty. I had that “tragic artist” future planned out for myself, that I’d either die or go insane.

MH: Connecting this to your work, I see humanity shining through in the form of social commentary, equality, and zero tolerance for injustice. Would you consider this to be fuel for your creative work?

CRJ: It is now. It’s been a process to get to that place, and there have been other things that have fueled it up until that point. But I think by the time I got to the Séance Series and beyond, I started to put my creative energies toward social commentary.

MH: This has been a tragic couple of weeks, with the mass shootings in Buffalo and Texas. As humans, we’re worn down and temporarily speechless. What’s your default when these tragedies occur? Do you feel like it’s important to keep making art, or should we respectfully put down our brushes for a while? Is there anything that artists can do to make a difference in the face of so much suffering?

CRJ: I once read a quote that asked, “Does the poet continue writing poetry when the house is burning down?” Which is a tough question because our house is burning in the U.S. at this point in time. I do sometimes question why I’m making art when things are so horrible, and what I come up with is that it’s what I’ve trained myself to do, it’s what I do best, so it’s what I can offer. So after something tragic happens and time has passed, I come back to making art about it. I’ve been doing a lot of political cartoons since 2016 and again, humor is a saving grace for me. I’ll often react to a tragedy with a cartoon that’s funny-not-funny, and something profound may come out of it.

MH: Have you ever considered another form of activism that may generate more immediate results? I can see you as a politician or human rights lawyer. Is art an effective vehicle for bringing about social change?

CRJ: It can be. I don’t know how often it is. I think of the work of Barbara Kruger – people pay attention to it because it’s savvy and sophisticated, but I don’t know any artists who can say with confidence that their work brings about social change. Lucy Lippard has always been a guiding light for me. She started out writing as an art historian, writing about “the boys” and writing very well, and then she became part of the feminist movement. But she managed to balance her critical writing about art with an incredible amount of activism. I march whenever I can and have been to DC many times. You’re just a body, but then there's a head count and it does signal something to people that maybe they need to pay attention to this issue.

MH: Finally, what for you is the most satisfying part of being an artist?

CRJ: Training oneself to think creatively. There are those moments when you’ve done a lot of sweating and head scratching and figuring things out, and then you hit upon something that’s so much better than what you ever dreamt of finding. We live for that!