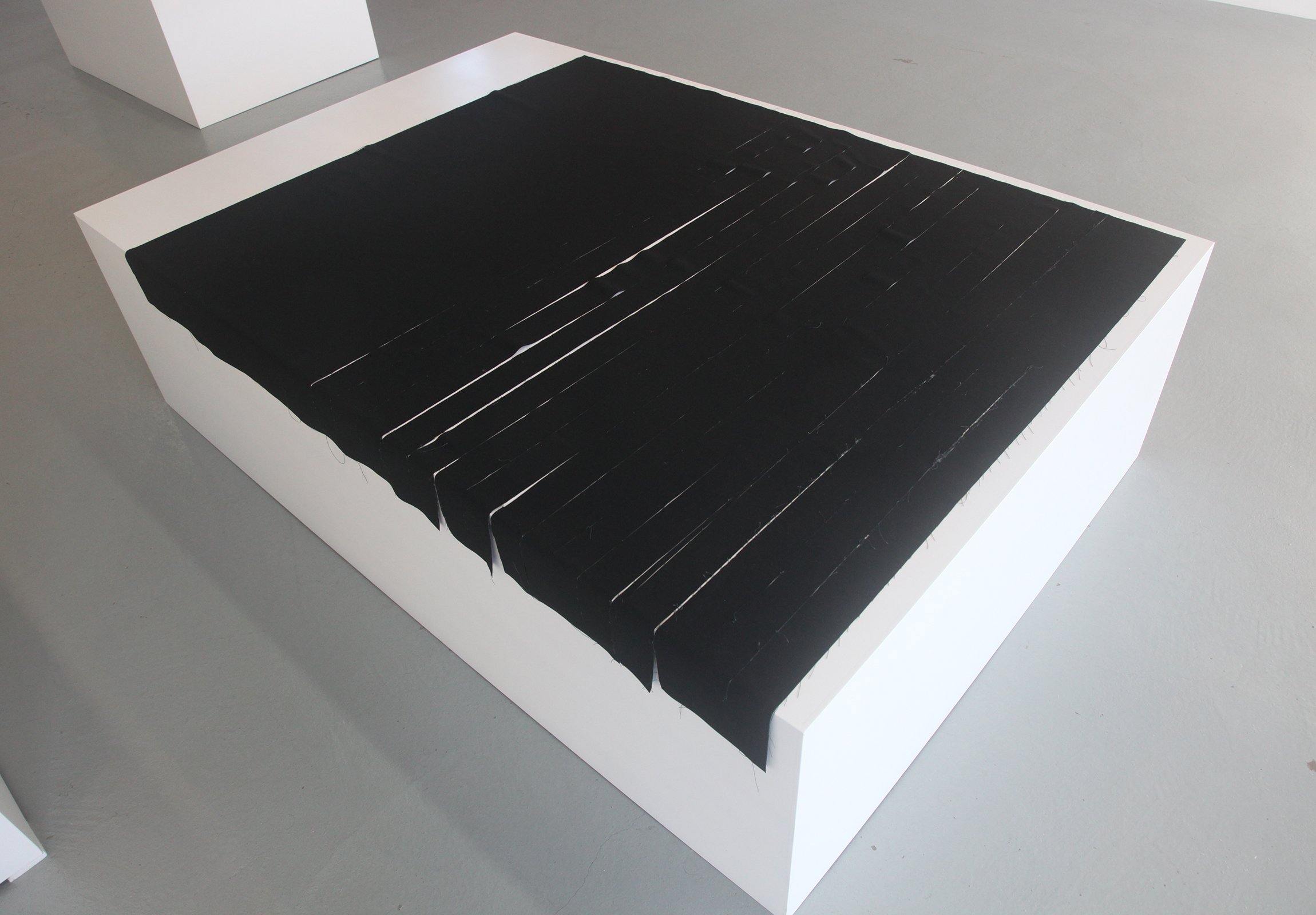

A few years ago, I went to ODETTA Gallery in Brooklyn to hear Janet Passehl talk about her intriguing work. She told a story that I’ve never forgotten and have retold many times. She was in a show in Connecticut, and happened to be in the gallery one day when a visitor walked in, looked around the gallery, and asked in a loud voice, “Where’s the art?” This type of comment would send most artists running to their therapist or the closest bar, but for Passehl it was a great compliment. Her work with cloth is not easily categorized or recognizable as art, thus it challenges our traditional conceptions about beauty and skill, process and product. Indeed, Passehl emphasizes that her work is not about the end product, but the piece is the process of making it. The finished cloth is an ongoing series of moments and a confluence of two wills: that of the artist and that of the cloth. She irons, folds, cuts, and weaves the cloth, while it exerts its own will upon the artist, shifting and breathing and asserting itself as a living, organic material. The collaboration is one of mutual respect, and we begin to feel the presence of the cloth as a separate being, a thing unto itself. In speaking of the finished works, Passehl says, “They’re always themselves, they’re always complete, and they’re always what they should be.”

MH: You started folding and ironing cloth in 1990, and you said in a way it was like drawing. How so? And what had you been doing prior to that?

JP: Prior to folding and ironing, I was using found cloth, hanging it, adhering things to it, and making marks with various materials. I was trying to find a way to make marks that would take longer and be more of a physical act, embracing time and movement. The folding and ironing became another form of mark making. I stained the cloth with tea or mud or whatever I could find, then the folding became an interplay between the stains, folds, and ghosts of folds that I’d already made. These became different kinds of lines with different qualities, and it all came out of drawing from life.

MH: What is it about cloth that intrigues you?

JP: I have a long relationship with cloth. I learned to sew when I was eight, and my grandmother and great-grandmother were seamstresses. As a child I was always designing and making clothing; if I wanted a stuffed animal, I’d make it. As an adult, I wanted to find a way to elicit an emotional response from the viewer without the use of imagery. Everyone has an intimate relationship with cloth; we all know what it feels like against our skin, and we have memories around it, so I thought that cloth would give me a way to build sympathy with my audience.

MH: So you start with a rectangular piece of cloth, and then you iron, drape, pin, cut, and so on. What happens during this process? Are you in control, or do you relinquish control? Does the fabric have a personality that needs to be respected?

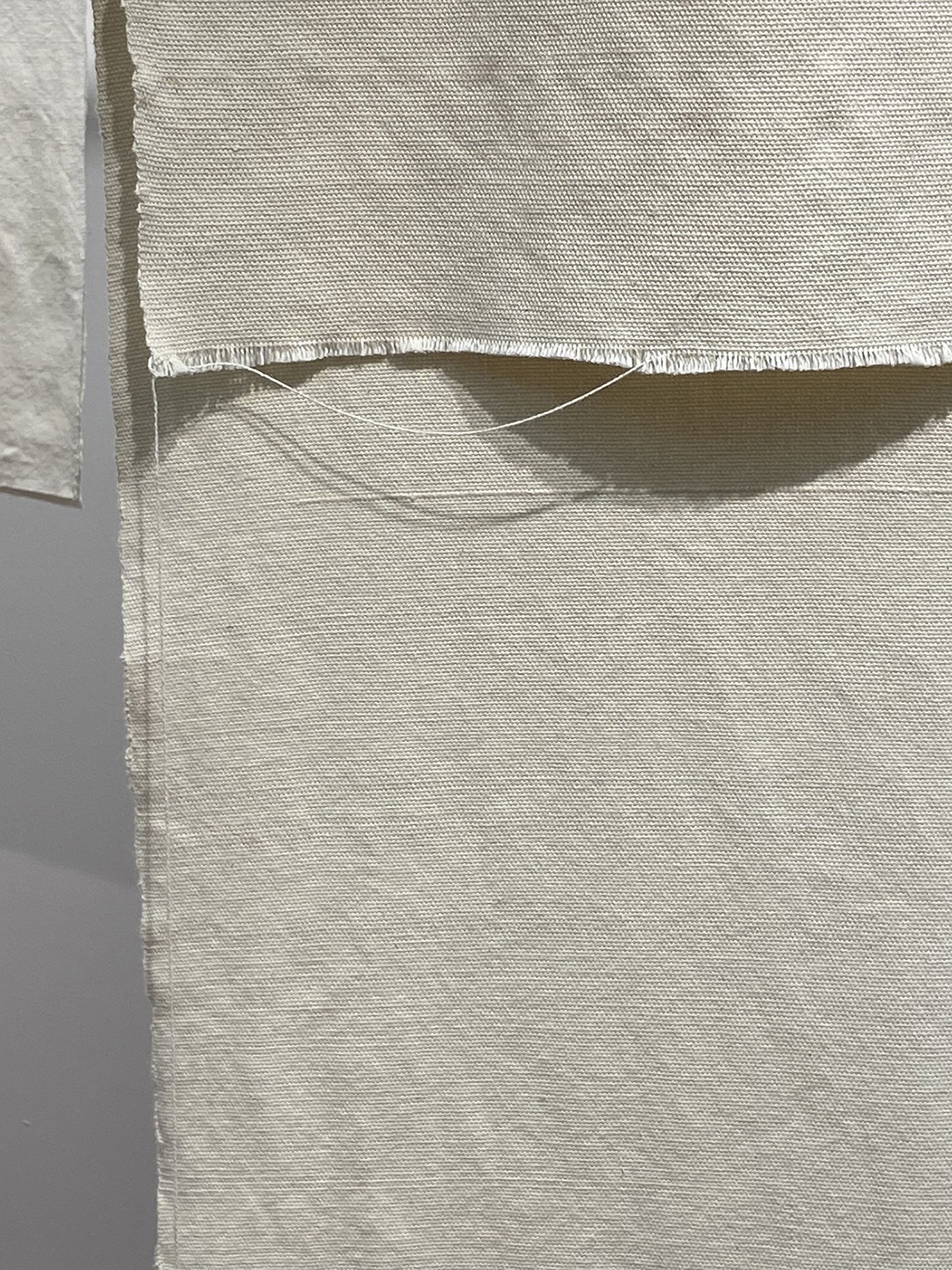

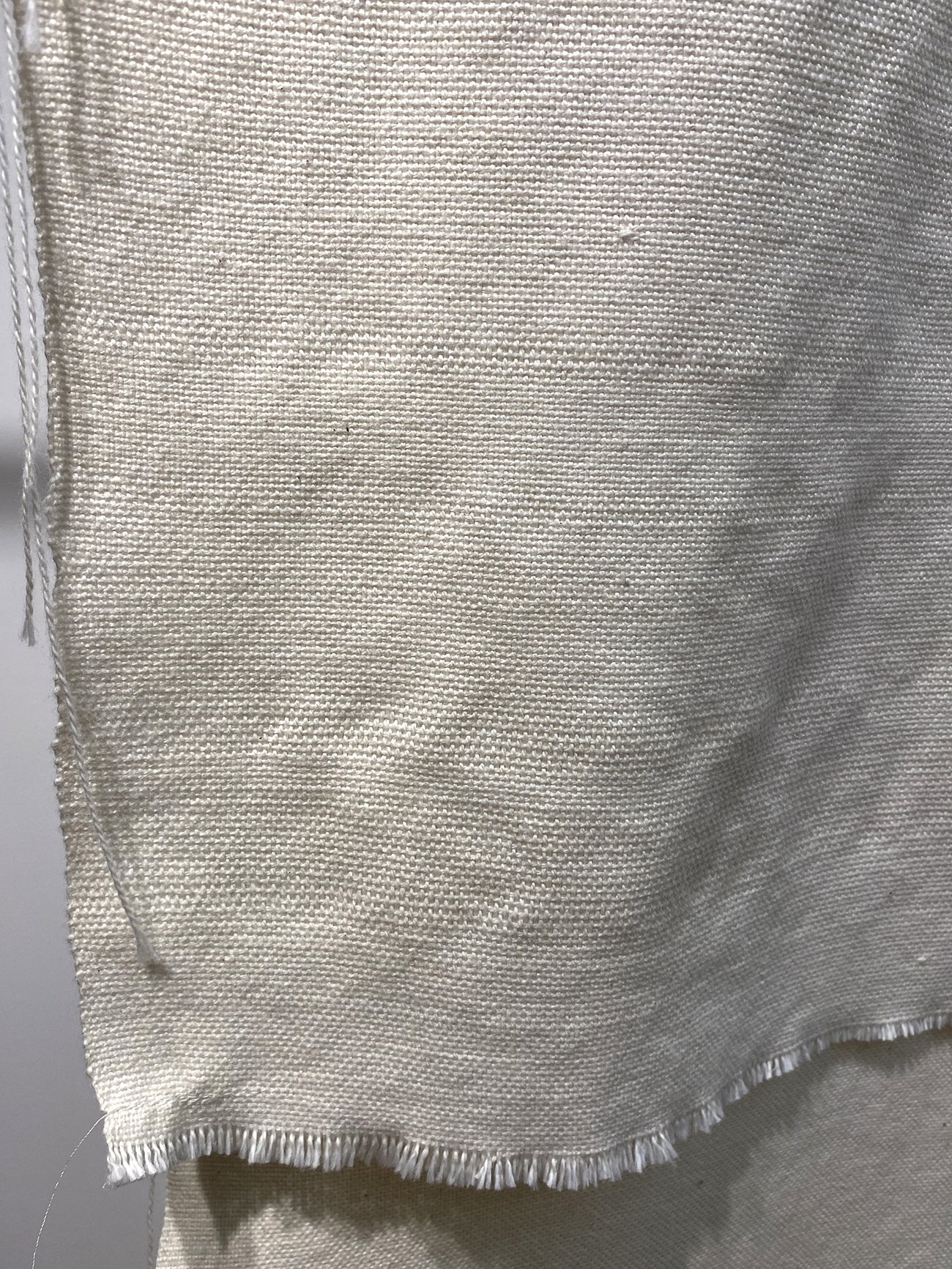

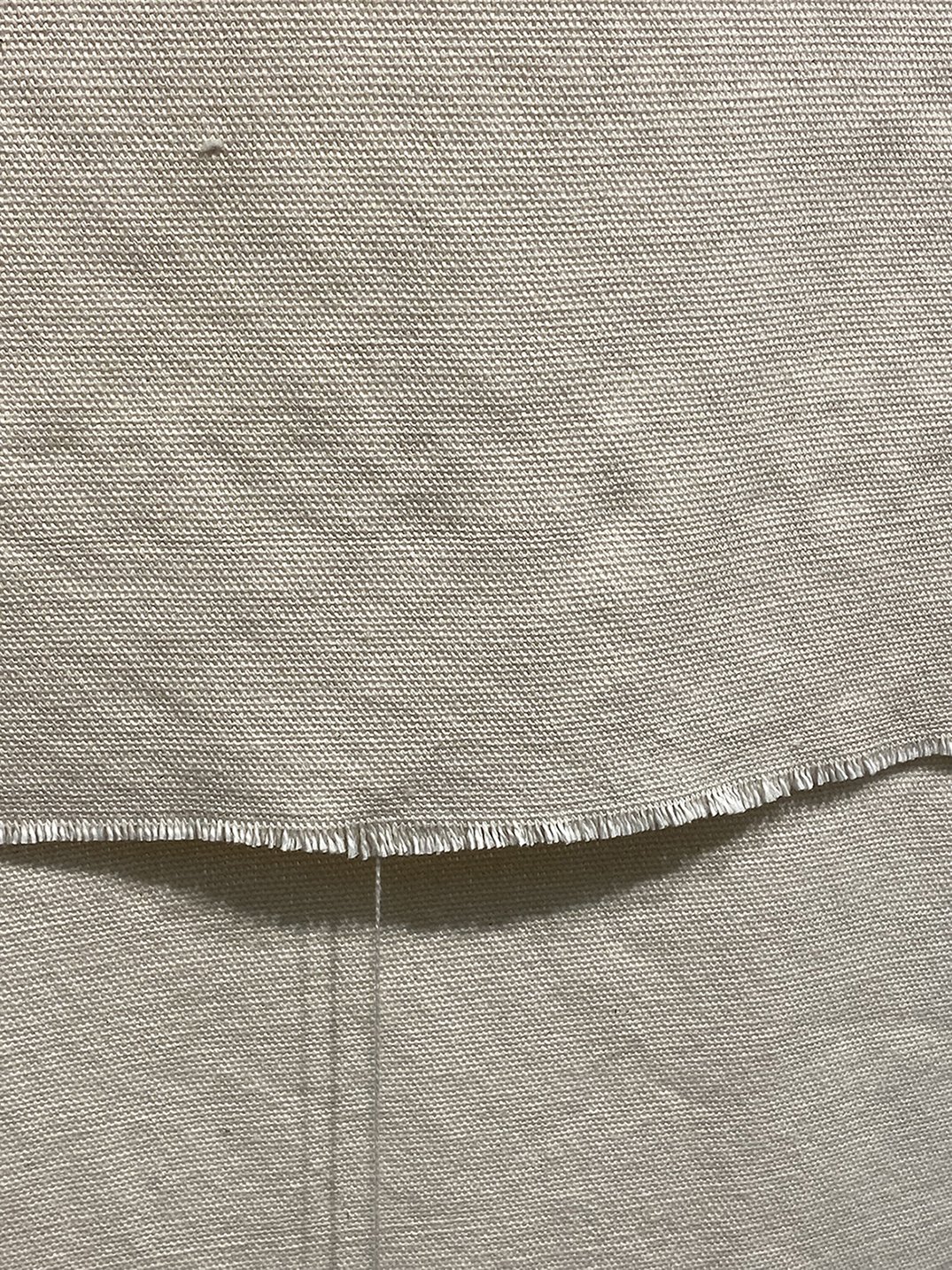

JP: Respect is a big part of it. I feel close to my materials, like I have a loving relationship with them. I’m interested in the personality of the cloth and how it asserts its own characteristics. I was trying to control it by folding, ironing, and cutting, but I couldn’t because it’s this living and organic thing, always shifting and asserting itself. This striving for control, and the impossibility of control, is a big part of my work. I try to work with the material so that it stays alive and breathes. I always think of cloth as having two wills: the will to flatness and the will to drape. I worked with both of those for a long time, and now I’m weaving the cloth.

MH: Right. How did you arrive at weaving? It seems like a natural progression, making your own cloth.

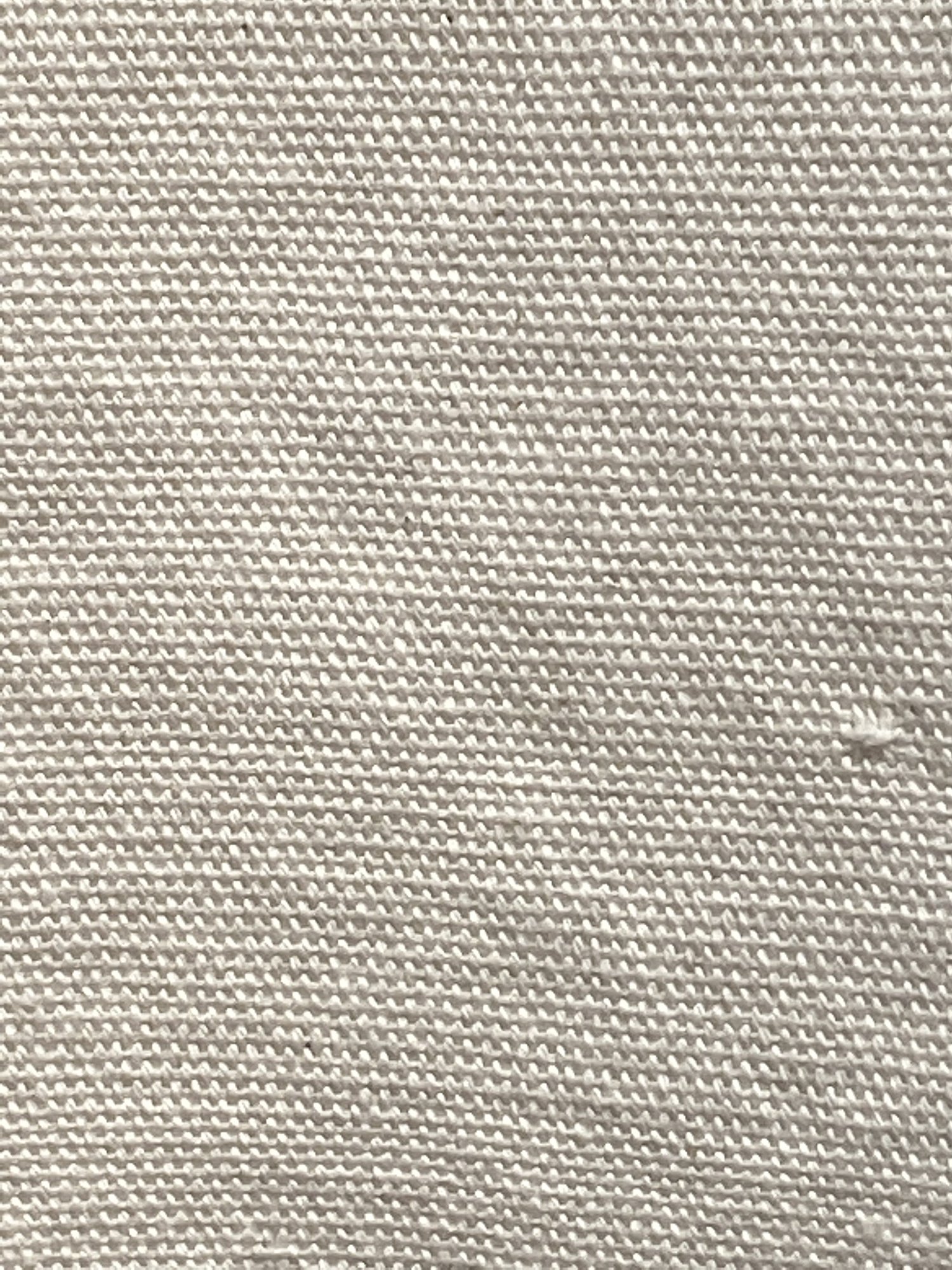

JP: Weaving is where the work has always been headed. It embodies everything that I’ve been concerned with, which is time, duration, space, process, awareness. The loom is a purely rational process, but irrationality works its way in, so there’s this interesting intersection between logic, intuition, and emotion. The resulting product has its own life, physical posture, and way of being.

MH: Cloth has so many variations in weaves and textures that each piece must have its distinct attributes. Do you find that you struggle with some pieces more than others? What would constitute a struggle in your process?

JP: When I’m weaving, I’m doing the same thing over and over but it’s different every time because of all the variations that can happen. Various tensions in the threads, threading the loom wrong – these things are a part of the process that I find enjoyable. In weaving class, I was the only one who didn’t mind having to go back and rethread. Working at the loom for me is something that takes as long as it takes. I call it “loom time” and it embodies my whole process.

MH: It sounds like the things that would normally be a struggle are the things you enjoy.

JP: Right. It’s important to me that it’s not just about the end product, but that the piece is the making of it. There’s no sense of production that I struggle with; I don’t feel like I have to hurry up and make fifteen of these. I just need to make something that speaks in the way that I want it to speak. And that takes as long as it takes.

MH: You mentioned that you wanted to create an emotional response in your work without the use of imagery and were drawn to experiment with cloth. And then you reduced your palette to black and white, which effectively strips away any residual sentimentality. It’s a wonderful challenge, to simultaneously starve and summon the emotions. Do you think you’ve been successful?

JP: First I want to say that my palette is not black and white. The pieces that I’m weaving are an off-white creamy color, and the previous body of work was light blue-gray. That's radically different from black and white. But yes, that’s what I set out to do when I started to iron – I wondered how minimal I could go, how simple and plain a thing I could present that would carry the information, emotion, mood, history, time, and duration. That’s been the challenge, and that’s really the crux of it. And based on what people tell me, there has been an emotional connection to the work.

MH: You use the term “radical simplicity”. What does this mean for you?

JP: I’m interested in how little I can do to create poetry. How something can be so basic and yet carry a lot of import is very important to me. This can be difficult for some people because it goes against their expectations of what art is.

MH: There’s a hint of something religious taking place in your work; a ritual or sacrament is suggested in the acts of cutting, draping, controlling, surrendering. And then there’s the use of fabric, which makes me think of a shroud or veil. I know you were raised Catholic, so I wonder if these themes creep into your work. Penitence? Transcendence?

JP: Not penitence! Possibly transcendence. My Catholic upbringing was early in life, in the 1960s, so the mass was still very aesthetic. There was the white cloth over the altar, the drapery, the incense, the iconography – these are things that I still respond to. I’m also interested in the idea of religion as the human search for meaning, and I’m moved by the art that’s been created because of those stories. I’m not a practicing Catholic at all or involved in any kind of dogma – I’m not even a seeker – but there seems to be something that I absorbed in my childhood about religion that shows up in my studio practice. Something about being with these materials; there’s the sense that I’m communing with a mystery.

MH: In Buddhism there’s the concept of tathata, or “suchness”, which is the essence of an object before ideas or words are attached to it. When I see the cloth, draped or lying flat, I experience it as a sort of primal presence that is at once immensely significant and essentially immaterial: it simply is, in the most profound sense. How would you respond to that interpretation?

JP: I like it – that’s how I respond to it. The work isn’t easily categorized. It’s not sculpture, it’s not drawing, it’s not a recognizable work of art. It’s something else, and that aspect has become important to me.

MH: I think of that great story that you told at your artist’s talk years ago, about the woman who walked into the gallery where your work was showing, looked around, and asked where the art was. I’m not sure why that touched me so deeply. I think the fact that you loved her reaction – indeed, that you were honored by it! – is so different from how most artists would respond. Can you say a few words about this?

JP: I like that the work is so quiet that somebody might not see it, particularly somebody who walks into an art exhibit with particular expectations. It speaks to the “suchness” that you brought up, that isn’t immediately recognizable as art. That’s not what it’s trying to be or needs to be.

MH: It seems that ideally, you’d like your work to disappear, or to be assimilated into the environment.

JP: Yes and no. It depends on what the environment is. It could be in a cluttered environment and disappear into the clutter, which isn’t at all what I want. Ideally, I want the work to be in a quiet space but then not jump out of the space at you.

MH: When an artist gives the viewer a boatload of visual stimulation and then adds a strong conceptual basis, there’s the sense that it’s all wrapped up, no further instructions needed. The viewer doesn’t have much to do except enjoy the piece, or not, but she doesn’t need to exert much mental energy to interpret it. What’s your thinking around this?

JP: I don’t want the work to be wrapped up because that’s not realistic; it’s not a reflection of the world or of life. I want my work to be open enough that people can have their own response and associations, and it may open another way of thinking about the world. I often have people tell me that they thought a lot about my work after they saw it, so I think it elicits a kind of curiosity.

MH: On the other hand, when an artist gives minimal visual information or stimulation, the viewer has to work harder to generate a response to the work. They either spend time with it and try to understand where the artist is coming from, or they simply don’t care, and walk away. How do you feel about this? Are you good if some people walk away? Are you ever inclined to explain it?

JP: Well, if everyone likes what you do, you’re doing something wrong. Everyone wants something different out of a work of art. If someone asks me about it, I’m more than happy to talk about the work. It’s not that I explain it so much as I talk about the things that are meaningful to me about the work and my practice. These are in-depth conversations, so it becomes a meaningful connection.

MH: There’s the sense that by denying the viewer those elements of art that are so appealing – color, virtuosity, verisimilitude – you’re exhorting them to find poetry in the mundane. It’s like you’re asking them to flex an aesthetic muscle that doesn’t get much use. I’m thinking of the solitary thread that droops from the cloth, the imperfections in the weave – these passages are so basic and unremarkable, but they take on poetic significance in the context that you’ve created.

JP: I hope so. There are a lot of little hints in the work, and hopefully people tune in to those, and then find those small moments all around them. There’s so much that happens at a minute level in everyday life, the nuances and juxtapositions that we encounter if we pay attention.

MH: It’s like you’re giving people a gift, offering them a way to see more deeply into things.

JP: That would be the ideal. Occasionally I’ve had people say to me that they saw things differently after seeing my work.

MH: In some ways I experience your work as an event. There’s so much activity that goes into making it: cutting and ironing, pinning and draping, and so on, then the piece is experienced by the viewer, and then it continues on to become something else. It’s a perpetual work in progress, existing in time and space, whereas a painting is a painting is a painting, frozen in time, regardless of where it hangs. What do you think? Is your work better described as an event, possibly a verb?

JP: I think of it more as an ongoing series of moments, living and breathing. It’s exciting to me to look at these works and know that they’ll always be a little different: they’ll move, breathe, hang in distinct shapes. And the weaving is the culmination of all that – it feels like a collaboration with the work, like I’m equal to the work, rather than its commander. It’s an ecstatic feeling for me. With my older work, I was trying to force the cloth to behave in a certain way, but the weavings are more open than that. They’re always themselves, they’re always complete, and they’re always what they should be.

MH: You said that you don’t have good or bad days in the studio because you have no expectations of success or failure. How did you arrive at this place? It sounds sublime.

JP: It is sublime! I think it came from realizing that it’s not about how many pieces I can make or sell or how I can get a dealer and all of that. That’s simply not the way that I work. Plus I've learned over the forty years of being an artist and writer to trust the process. I just keep looking, thinking, reading, and most of all inquiring of my materials and processes, and I find the work I need to make, and it will find its way out into the world.

MH: Did you have to give up something to arrive there?

JP: Nothing except my illusions about being a hugely successful artist who has lots of shows and sells a ton of work. Once I realized that’s not the most important thing to me, then I was fine. Because as much as I'd welcome commercial success, I don't want it to get in the way of my creative freedom.

MH: Any final words?

JP: I’m very ambitious, but my ambition is about making the absolute best work I can make, and the only way to do that is to be totally honest and unsparing. It took me a while to get to this place, but now I’m comfortable with it, and it feels beautiful.