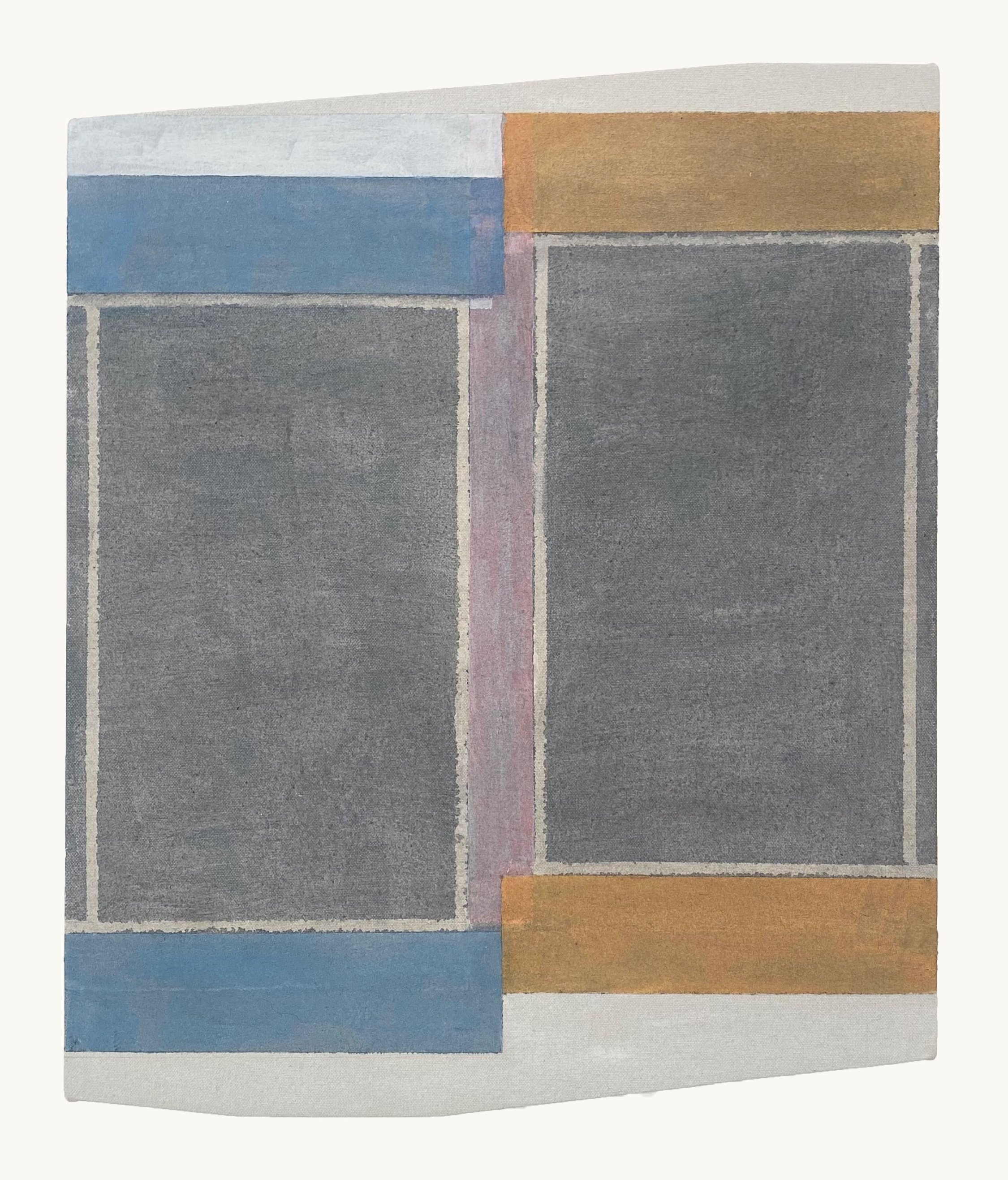

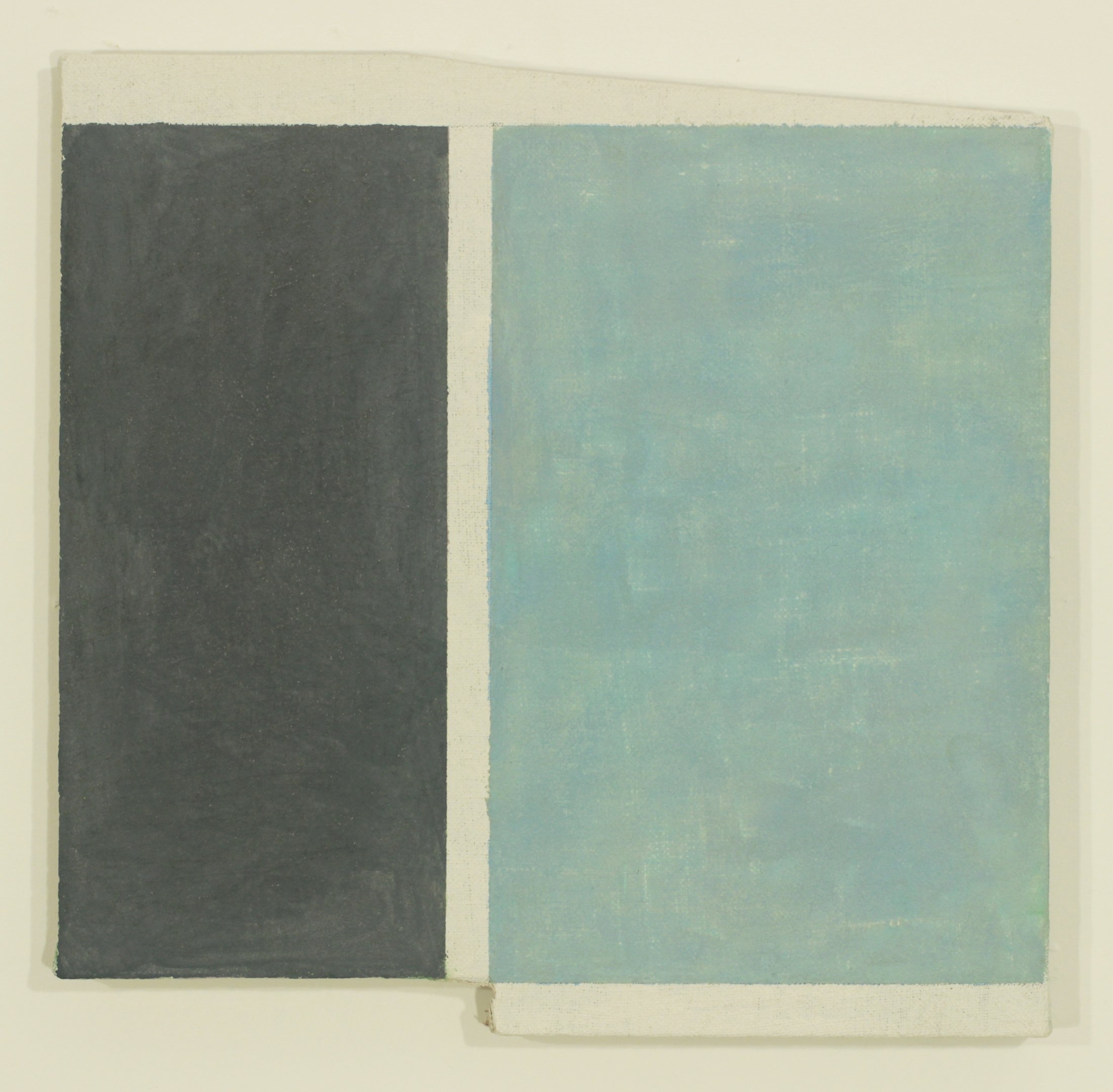

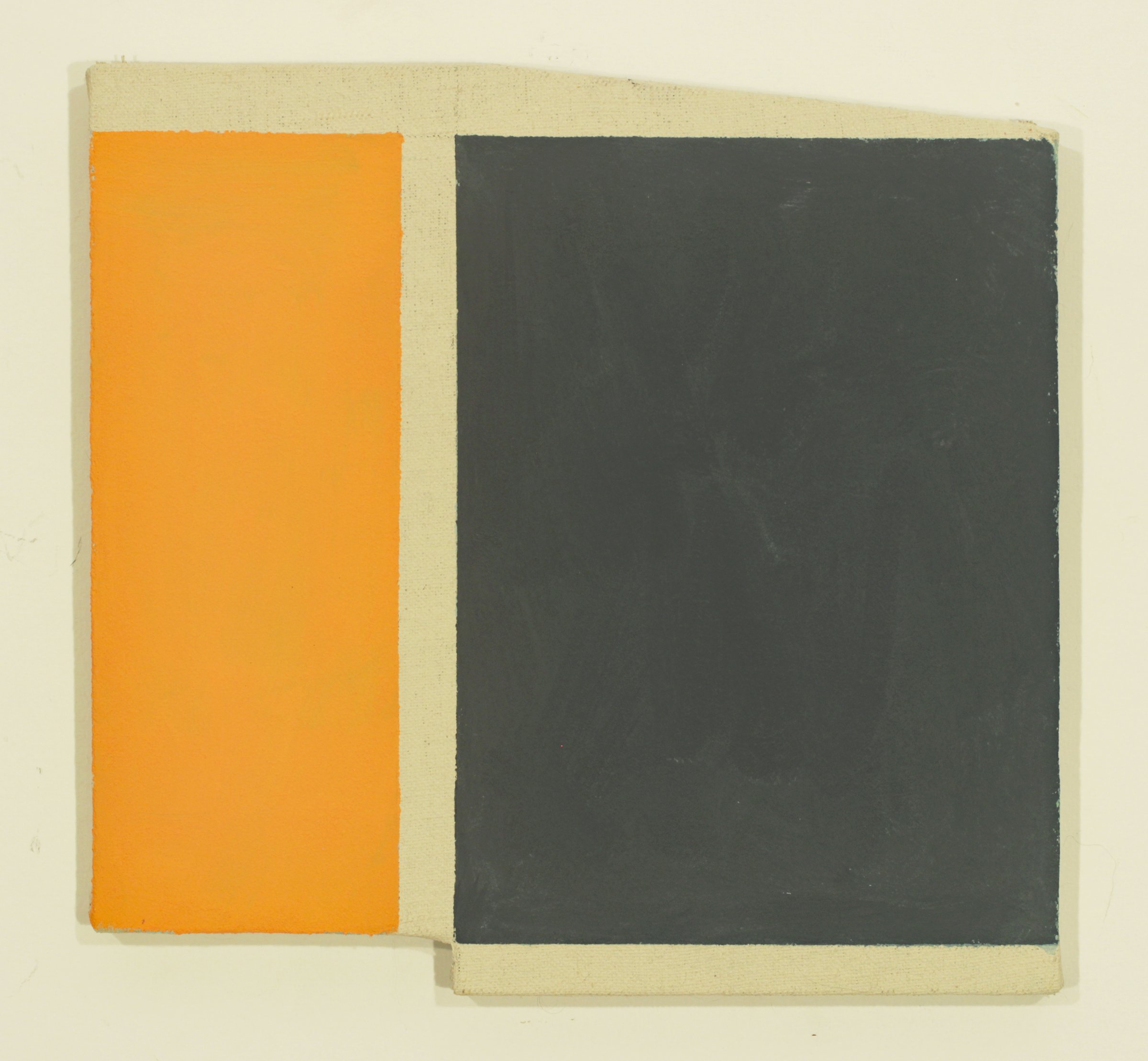

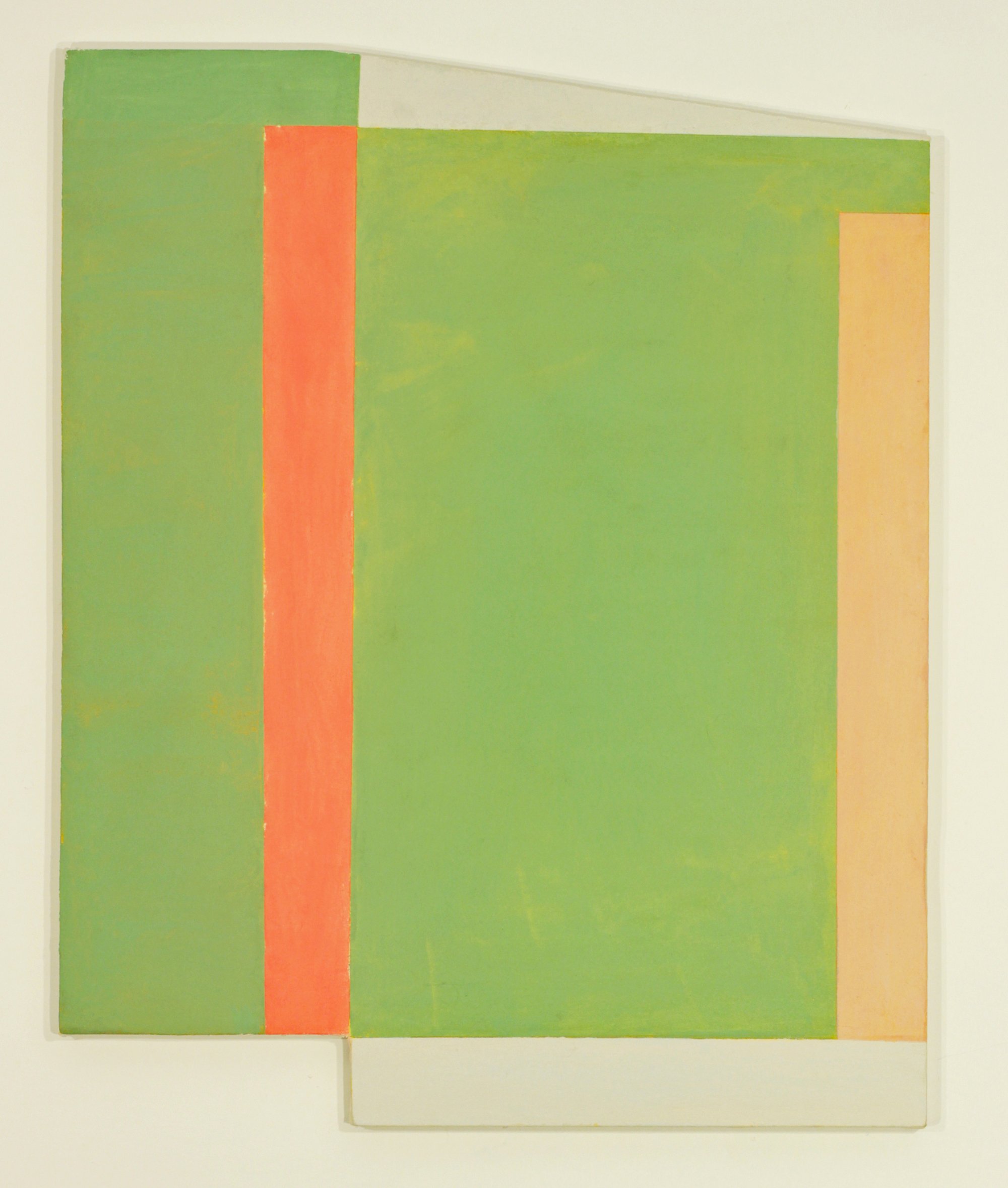

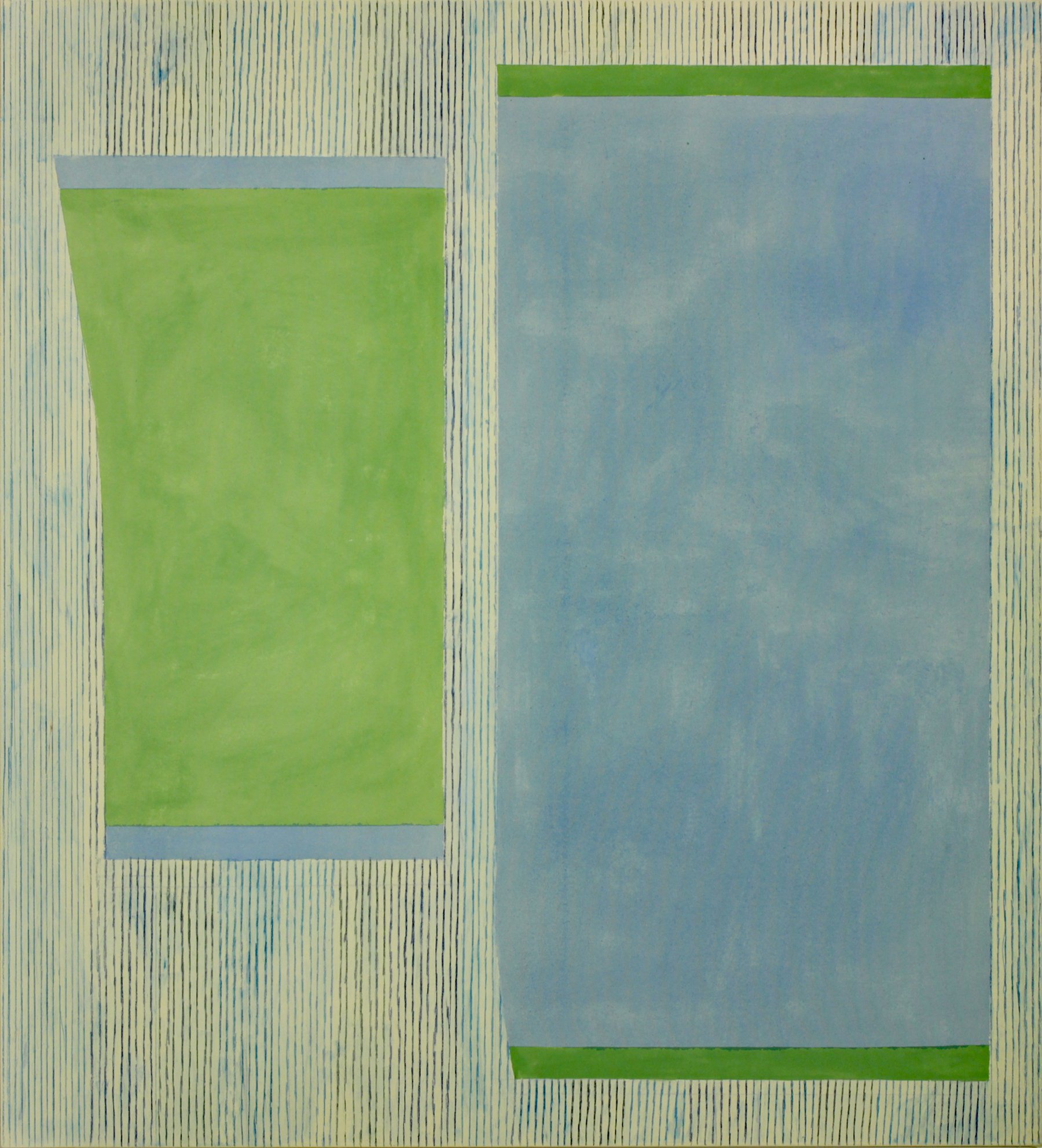

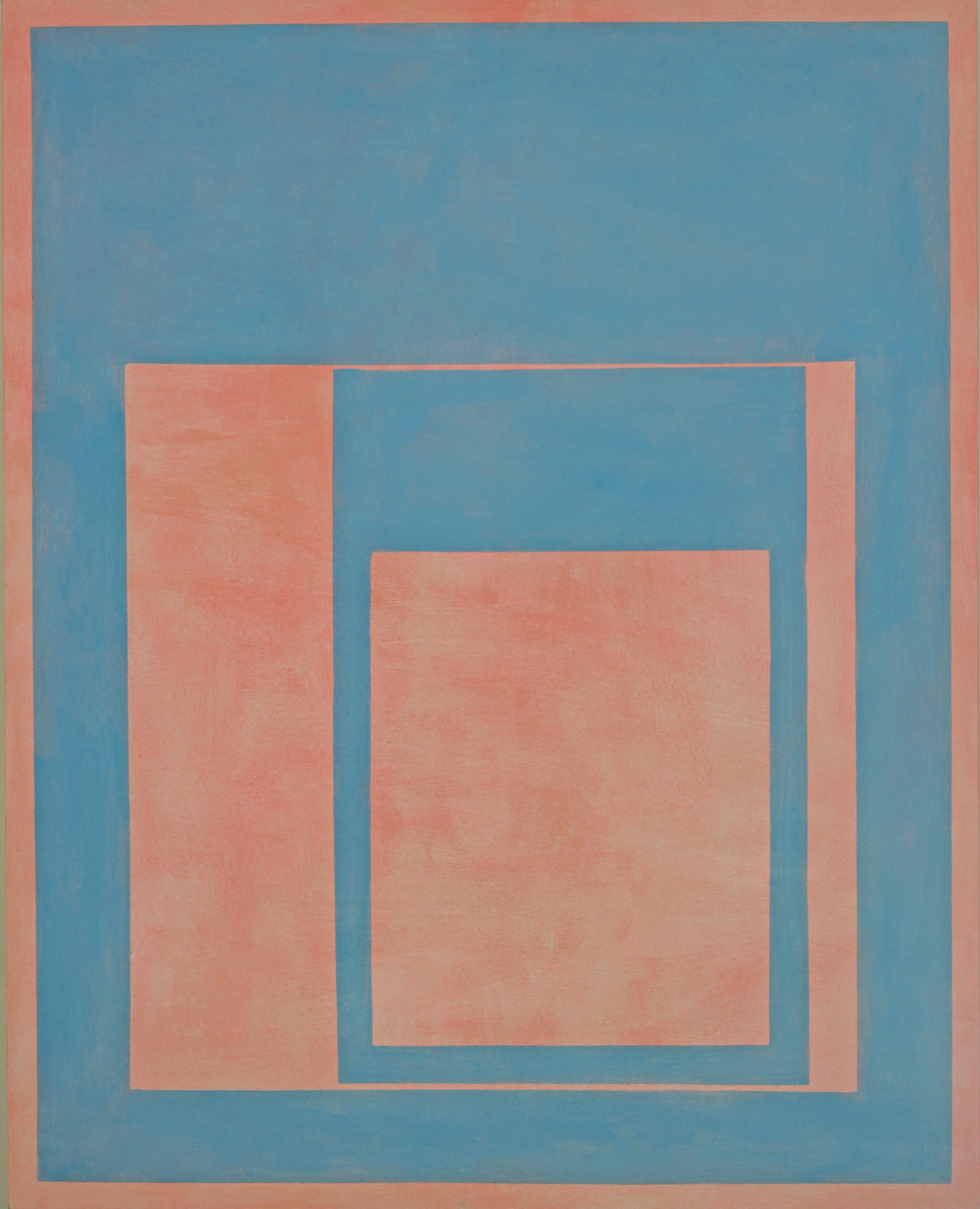

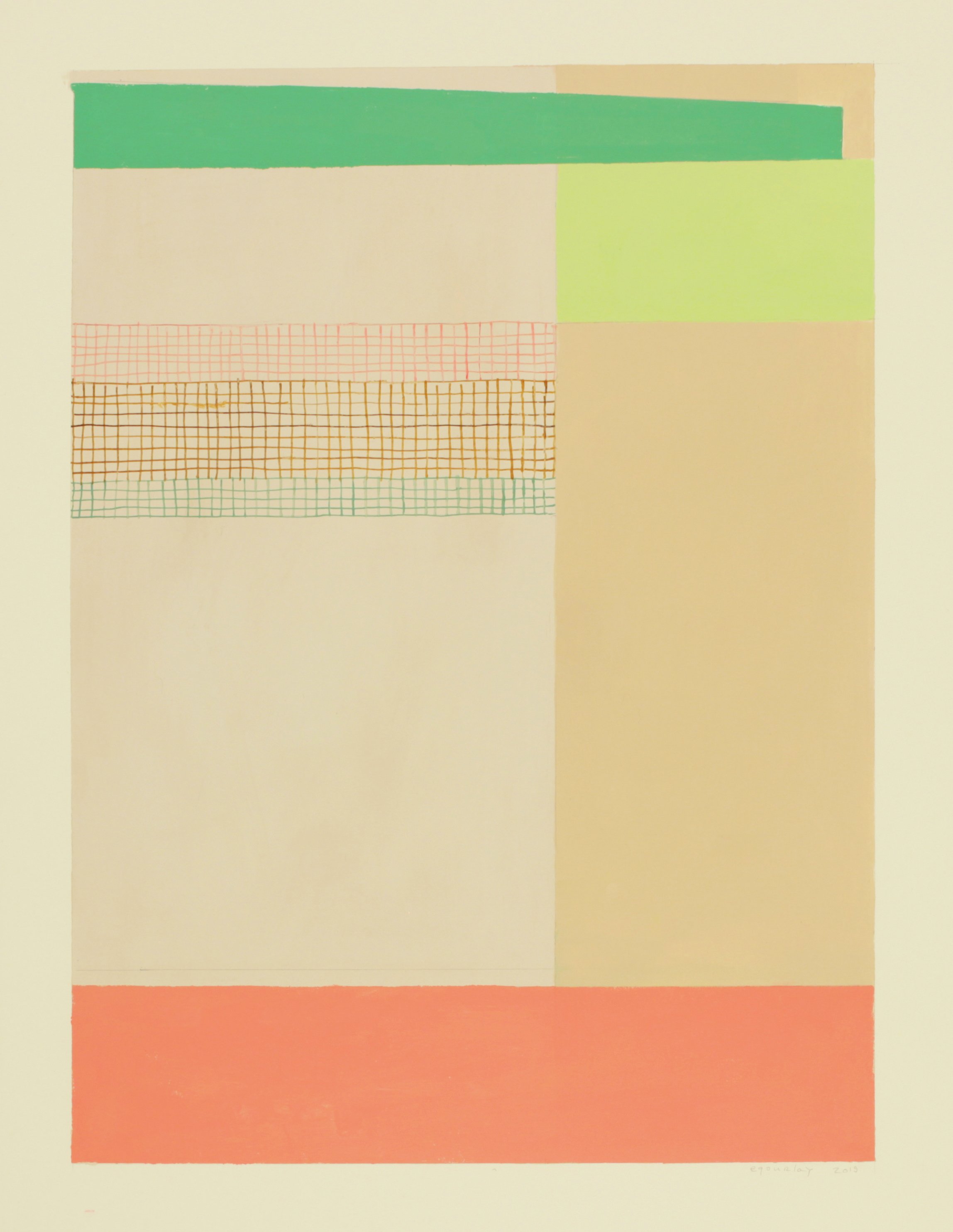

The best way to get to know an artist is to spend time with her art. It’s there that her soul lies and her heart beats, and where her highest self is revealed through pure form and color. Elizabeth Gourlay’s paintings are at once radiant and understated, in keeping with the modest temperament of the artist. She applies thin washes of gray paint over planes of vibrant color because, in her words, “It’s hard for me to allow a color to pop without pushing it into the background.” The result is a vibrance that is more felt than seen, like clouds bursting with light from an invisible sun. And yet she allows her brilliance to shine every so often: here a thin line of lemon yellow, there a block of blazing orange. Through subtle juxtapositions that are second nature to the artist, Gourlay’s muted palette makes it possible for color to reach its highest potential. While our conversation took some interesting turns, it always came back to color and paint. Clearly this is the artist’s passion, and her depth of knowledge on the subject is extensive. In her show “Unexpected Windows” at Kenise Barnes Fine Art, the canvas departs from the traditional rectangle and assumes a shape that is integral to the painting. The irregular shapes are unexpected windows through which we catch glimpses of the artist’s thought process as she pushes color and form in unexpected new directions.

MH: Most artists work from nature at some point in their career. In art school we paint the figure, landscape, still life, all that good stuff. But later we make choices about what we want to paint, and whether we’re going to continue to work with representation. When did you move into pure abstraction? Was it when you were in grad school at Yale? Was it a gradual shift, or were you always drawn toward nonrepresentational art?

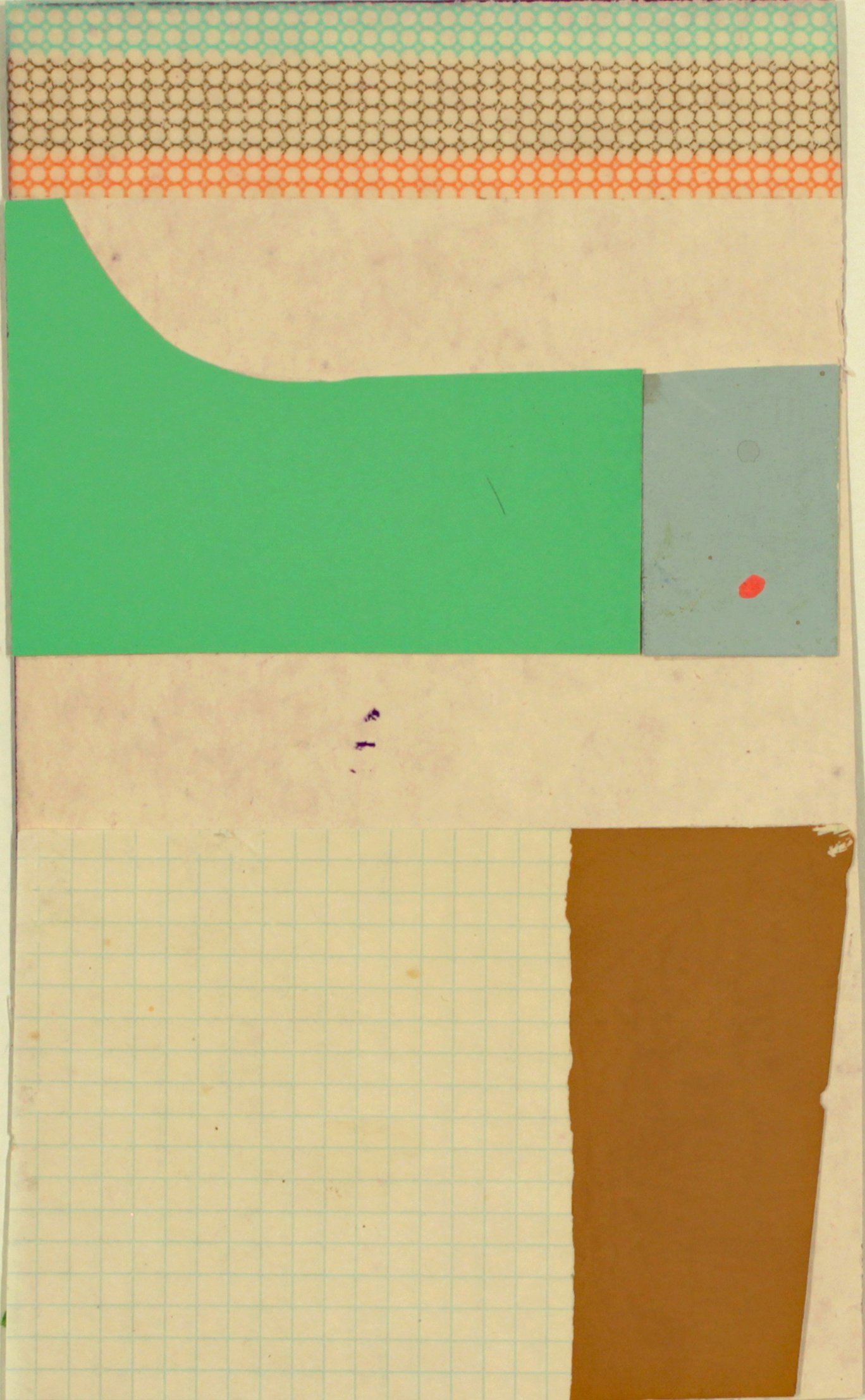

EG: It was a gradual shift. I started working with pure abstraction in 1986, but it was quite different than what I’m doing now. At Yale I was still working figuratively, doing circus paintings that were large and loose and becoming increasingly abstract. The big shift happened when I moved to New York City. I was living on the Bowery and my work made a huge shift into abstraction. I was making gestural shapes that relate to what I’m doing now, drawing with a pencil, and then painting on top of that. I got to show these at the Drawing Center in 1986, which was an amazing opportunity for me. After that I started experimenting with a lot of things – encaustic, collage, small sculptures, and eventually I started working with geometric shapes.

MH: Your paintings appear to be about pure form, color, and relationships. But I see the barest hints of imagery in your work: windows, staircases, landscapes. How do you feel about your work being interpreted as representational?

EG: I don’t see it that way, but I don’t mind if people do. I’m happy for people to interpret it the way they want to. I’ve always been inspired by nature, and I enjoy representational art. Morandi is one of my favorite artists.

MH: In one of your paintings, I see a Tibetan nun wearing a bright orange robe, descending a stone staircase while chanting Buddhist mantras. Is that totally irritating?

EG: It’s not irritating, it’s fascinating because that’s not what I was thinking about at all. The color is never symbolic for me, but I’m happy if people read into it. Sometimes my work has a quirkiness that makes people see things that I didn’t intend.

MH: Your use of color is for me the most satisfying element of your work. I can’t help but think of Albers and the interaction of color, and I wonder if he’s been an influence in your work? Your muted palette creates a field against which the colors pop and vibrate. Can you talk a little about your use of color?

EG: Color has been the most important element for me in my work since I started my schooling. When I started teaching color, I returned to Albers and taught my students how to use color interaction. I had them mix achromatic grays, and that’s something I use a lot in my own work. I love gray; I think it comes from living in Edinburgh, Scotland, which is a gray city. That’s where I first learned about color. Lately I find myself choosing some odd colors that I wouldn’t normally choose, like this new cobalt violet that I’ve been obsessed with for over a year now. I’m also using powdered pigments and mixing the paint myself, which I’m really excited about. I’m always experimenting with odd combinations and thinking about how to make colors pop. But it’s difficult for me to allow a color to pop without pushing it into the background.

MH: There’s considerable variation in your visual vocabulary. Sometimes I think of Agnes Martin, other times I recall Diebenkorn and his flat planes of color. But it’s rarely just one thing – all these elements are thrown together in a formal way, and my eye keeps moving around the canvas. Is this movement something you think about?

EG: I definitely think about movement. As a piece develops, I’m always thinking about where the eye is moving. The edges become very important, both the edges of the forms and the edges between forms. The eye should stay engaged on the piece, but your experience must go well beyond. A big shift happened about ten years ago, when I was in Italy for the summer. I’d be working in the studio and the sound from the street would come up through my window and bounce around the room. It was a recurring sound and I experienced it as a shape, echoing around the room. This, combined with seeing and experiencing the architecture of the buildings in the town, had a big influence on how I thought about shapes in my paintings.

MH: It seems like the way that you paint must be really satisfying.

EG: It can be, but I keep changing it, because I can’t repeat myself too many times. And then it’s satisfying to work with scale, going from small to large and back to small. But yes, I enjoy it. If I’m having a good day and I’m on a roll, it’s super satisfying. But it’s not consistent.

MH: I’m also interested in how/when/why you chose to depart from the traditional rectangular canvas to work with shaped panels. They’re so satisfying visually – I can imagine that it’s extremely pleasurable to paint on them. Does the departure from the rectangle influence how you approach the canvas? Are your formal choices affected by the contours of the panel?

EG: Yes, I find that the shaped panel strongly influences the composition. Sometimes when I work on a rectangle or square there are overwhelming possibilities, but the shaped canvas gives me a direction. In some cases, it’s like the shape tells me how to paint the piece. I didn’t realize until I started making the shaped pieces that I was probably influenced by my father. He was an architect, and I grew up in a house that he designed. He worked locally, so I’d go to sites with him and help him measure.

MH: What does pure abstraction give you that representational art does not?

EG: I kept up with painting the landscape and figure until maybe ten years ago. This was mostly for commission work or teaching exercises, though I’m sure color and other ideas crept into my own work. Whether or not a piece is representational is not why I’m drawn to it; it’s more about responding to the color, shape, composition, or energy of a piece, and if it’s speaking to me or not.

MH: Is there freedom when you’re untethered from representation, and if so, can you define this freedom? Does it ever feel like a burden, or is freedom your ally?

EG: There are so many choices that sometimes it’s helpful for me to have some rules, even if I end up breaking them. Like, I’ll decide to work on paper one day, or collage, or paintings. It gives me direction. The small collages and works on paper help me figure out the larger pieces.

MH: I ask this because freedom often creates anxiety; specifically, the fear of making a bad decision. In the presence of pure freedom to paint whatever I want, it’s an issue just to go into my studio, much less pick up a brush. Does this ever come up for you?

EG: Oh yes! I was ready to abandon the shaped pieces before I ever showed them. I was going to go back to the rectangle.

MH: So how do you push through? Is it sheer will?

EG: Yes, and the fact that I get so much joy from working. I’m not happy doing anything else. When I feel stuck on something I just try to push through.

MH: I envy the Italian Renaissance artists whose creative work was spelled out for them: Nativity, Last Supper, Crucifixion, Repeat. They never had to think about subject matter; all they had to do was bliss out with paint or marble or whatever. I’m wondering if you sometimes experience obstacles in making choices about the work. Do you secretly wish there was a rule book that you could refer to when things get dicey?

EG: I try to make my own rules to keep going. I work well with commissions, because they give me parameters, something specific. There’s this quote from Pat Adams, who taught at Bennington and Yale, and I ran into her at the Vermont Studio Center: “It’s important that artists not return to the Renaissance where they were given topics and subject matter. I think we need to provide evidence. Artists who sit and work quietly are allowing themselves to come into it. They are providing evidence of our species: what impels us, who we are, what we are, what we do, what we are thinking.”

MH: I’ve heard it said that all paintings are self-portraits. If so, it follows that each painting shows different aspects of the artist. From one painting to the next, do you notice variations that may represent contrasting facets of yourself? Do some finished pieces feel meditative, and others agitated?

EG: That’s interesting. I don’t think about that necessarily, but there’s a piece in the show in Kent that I saw as a self-portrait. It shows my thinking process, how I edited and changed the painting. I’m always editing things out, but if I’m feeling agitated, I try not to put it in the work. That’s when it’s better for me to do something else, like stretch canvases.

MH: Back to color. I have immense respect for how you handle it. You paint a field of saturated color – let’s call it ‘Tibetan Nun Orange’ – and then you paint over it with a tertiary gray, so that the orange is now barely visible. Nevertheless, it is visible, if understated. It’s as if the gray amplifies the color by restraining it, like water penetrating a dam, or sunlight filtering through clouds. It must be deeply gratifying to have found a way to manipulate color in such a way that it transcends the medium and creates luminosity.

EG: I guess it is, but it still feels like a day-to-day struggle. One piece will be good and then the next one will be a failure, so it’s not like I do a series of fantastic paintings. But sometimes it feels like there’s something that moves through me. There’s this great quote from Paul Klee: "From the root, the sap rises up into the artist, flows through him, flows to his eye.” I think about that all the time. When it’s working, it’s something that flows through the artist, and they’re not necessarily aware of it at the time.

MH: Did you ever consider another occupation? I don’t mean hedge funds or dentistry, but writing, music, anything like that? I see you as a poet, possibly a dancer. Have you always been a visual person?

EG: Oh yes, from a very young age. I have an early memory of one of my parents’ friends, an artist, showing me how to work with watercolor to make clouds, and I remember being completely mesmerized. Both my parents encouraged me from a young age to be an artist. The other thing I loved doing was writing, and I play the piano, but it’s hard to do everything.

MH: You mentioned that this show at Kenise Barnes is the first show of your shaped panels. How do you feel about showing them? Is there a way that you’d like people to approach your work when they see the show?

EG: I’m happy about the reaction to the new work, and I hear that it’s been well received. I’m pretty open to how people choose to see it. I’d like my work to be approached with an open mind, as if they were entering a new building or architectural space. I think the color and form will speak for itself.