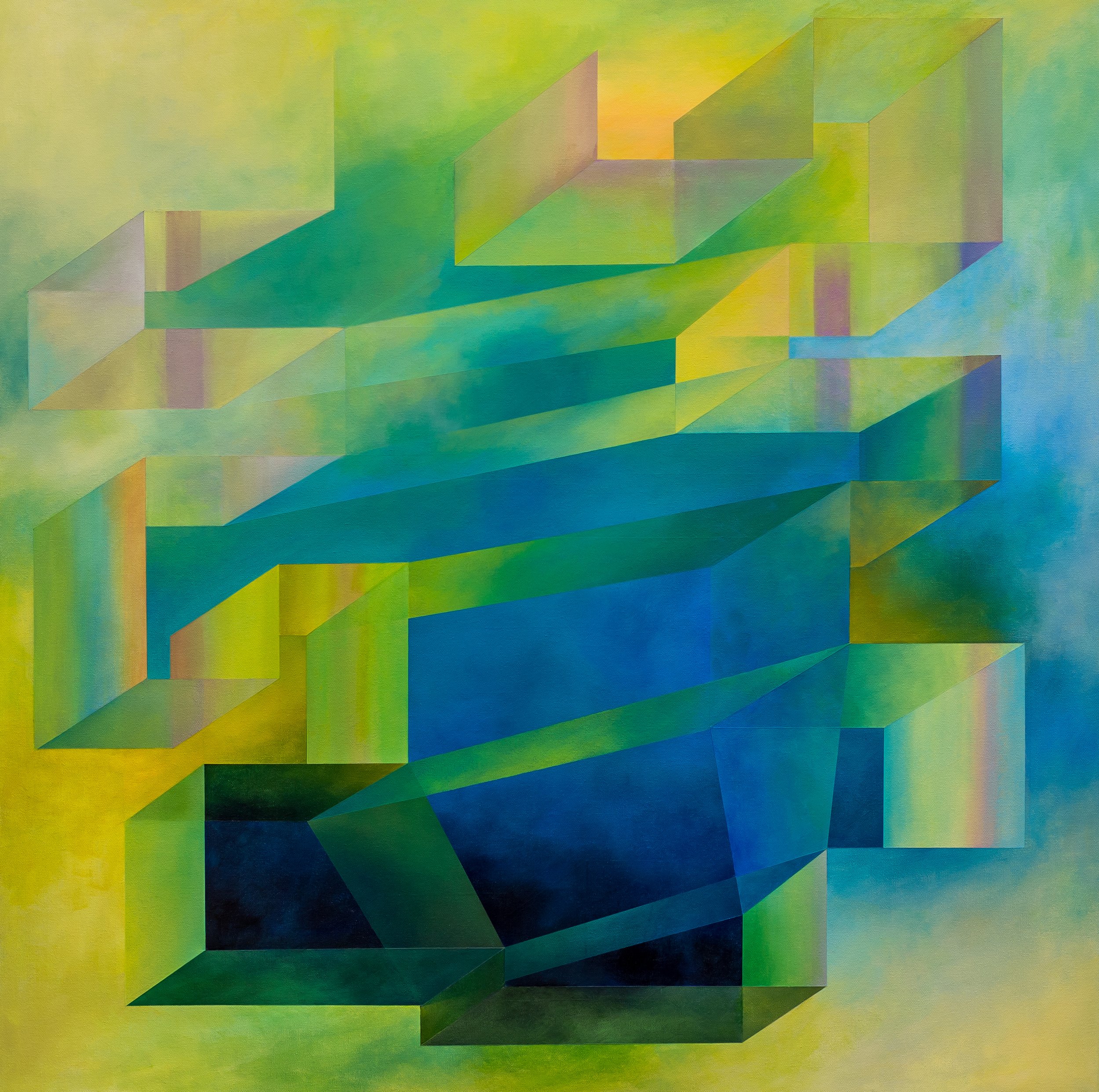

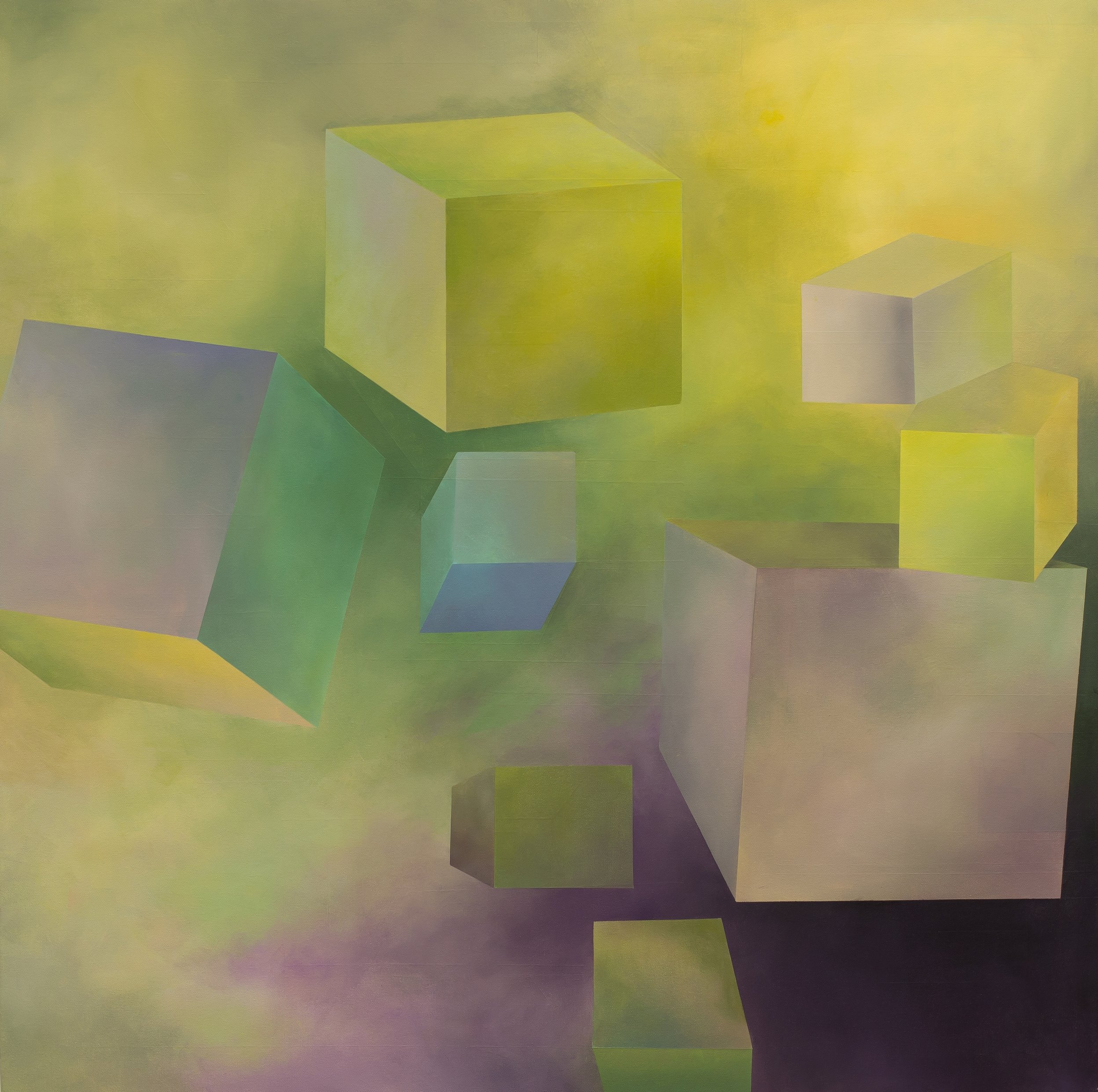

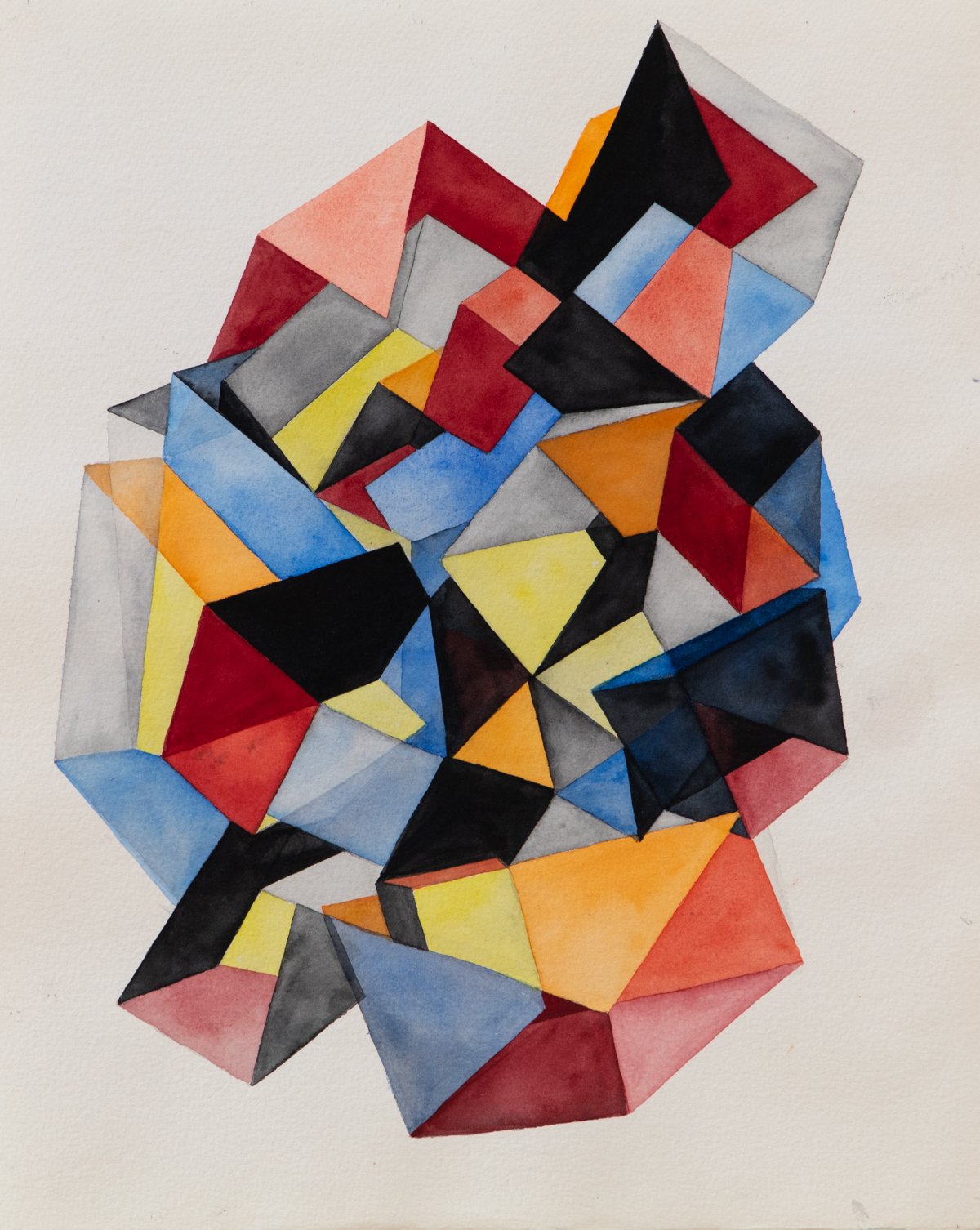

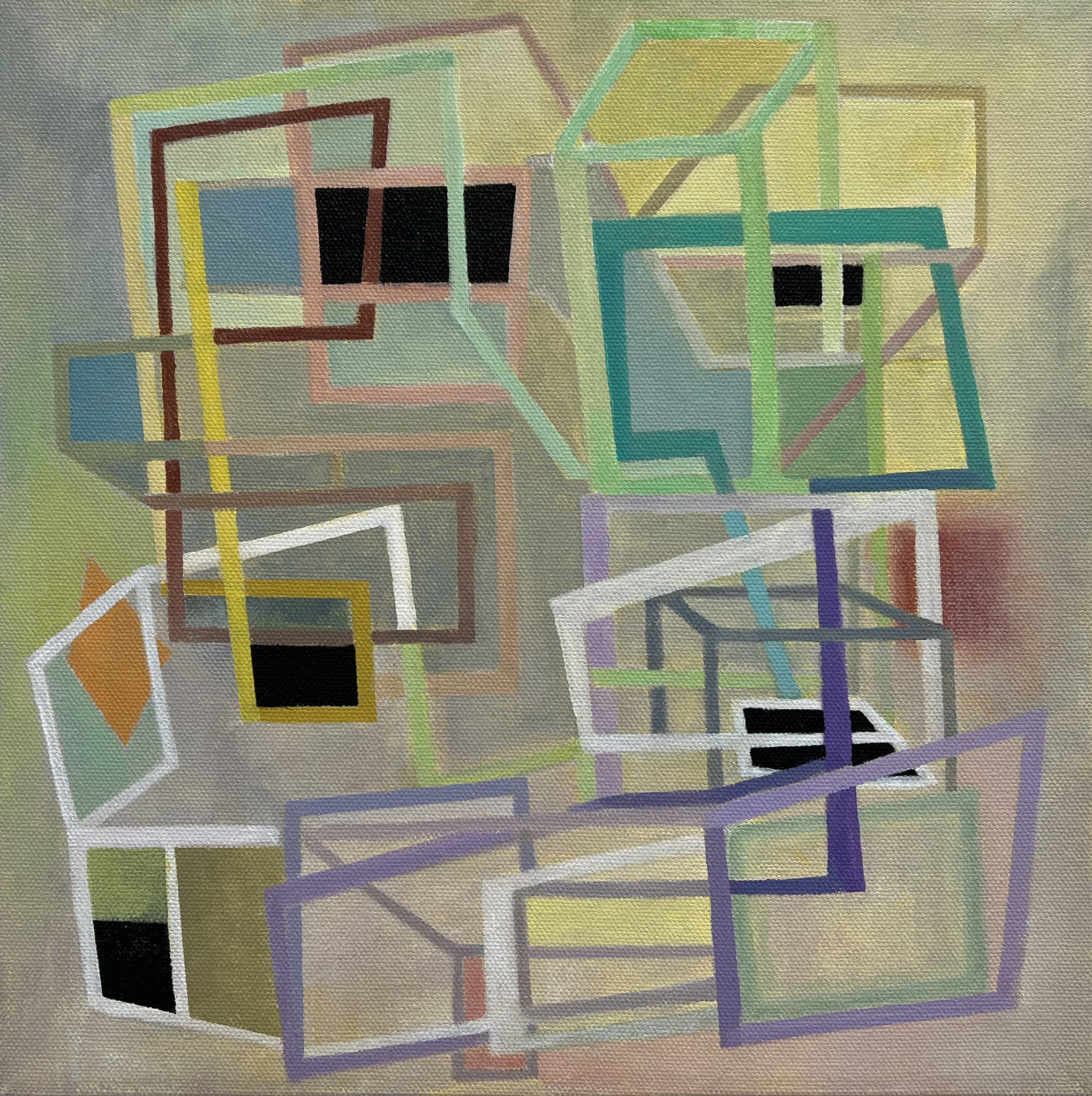

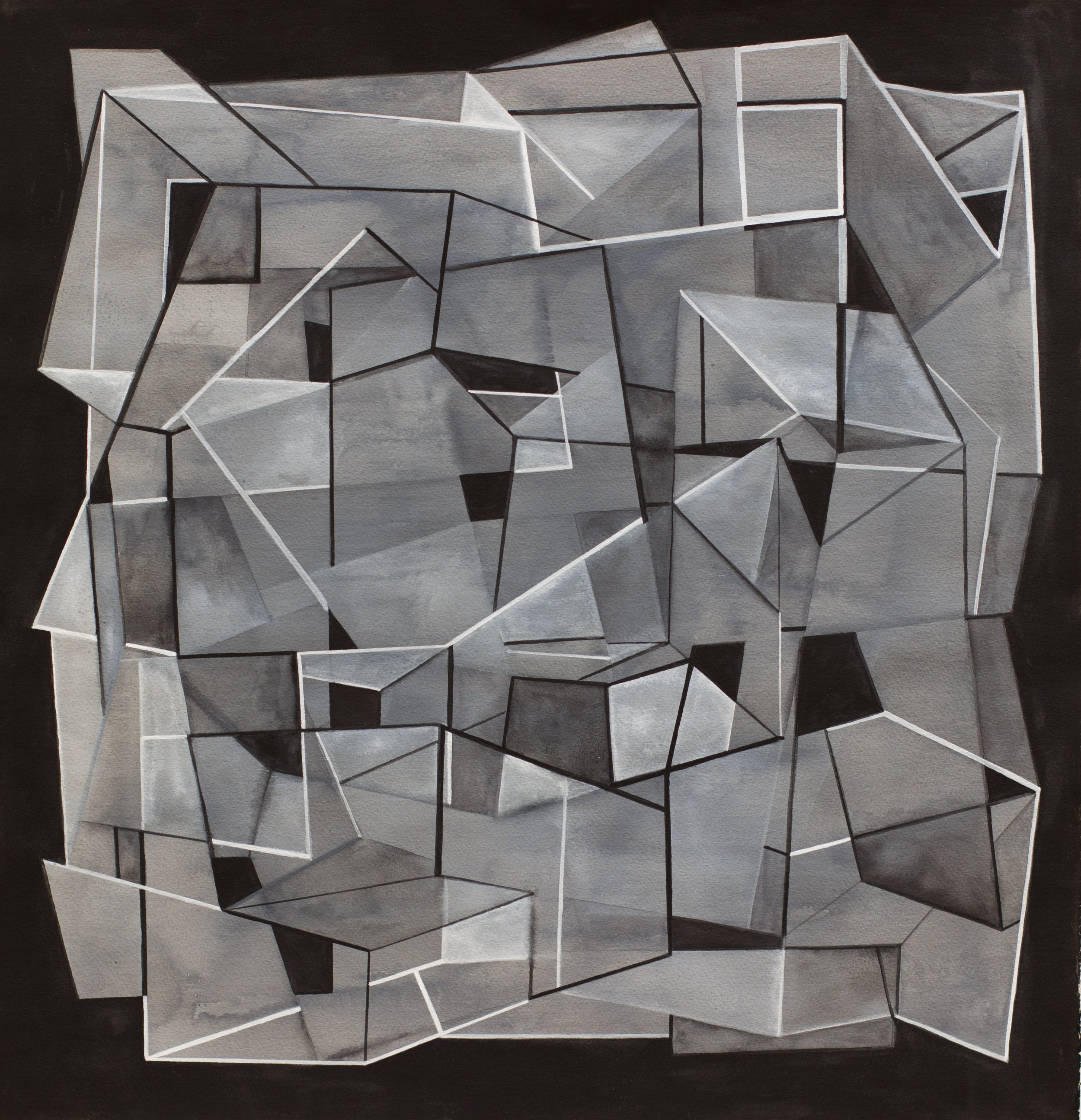

Ann Provan’s show at the Garrison Art Center, “Inner Window”, consists of sixteen paintings that read as meditations on atmosphere and light. Geometric forms float in a field of saturated color, creating architectural structures that shift and collide in ambiguous space. But the ostensibly serene paintings contradict the temperament of the artist, who became agitated as we talked about her studio practice. “Each piece is a terrible struggle,” said Provan. “I never know how it will turn out.” We discussed the difficulties that we face in our studios, from the continual effort to push each piece toward its highest potential, to the personal demons that torment the artist when a piece goes south. The struggle is real and complex and widely understood to be an unavoidable aspect of the creative process. Provan’s paintings should be seen as the work of an artist who is deeply committed to finding that elusive thing that cannot be easily realized in a painting. Her abstract geometries are beautiful to behold, but they open an “Inner Window” that is much deeper and more complex: the ongoing struggle of the artist to overcome all obstacles in search of the purest form of self-expression.

MH: Your show at the Garrison Art Center, “Inner Window”, features sixteen paintings, all painted in the last several years. I know that you’ve worked in other mediums as well. What’s your background as an artist?

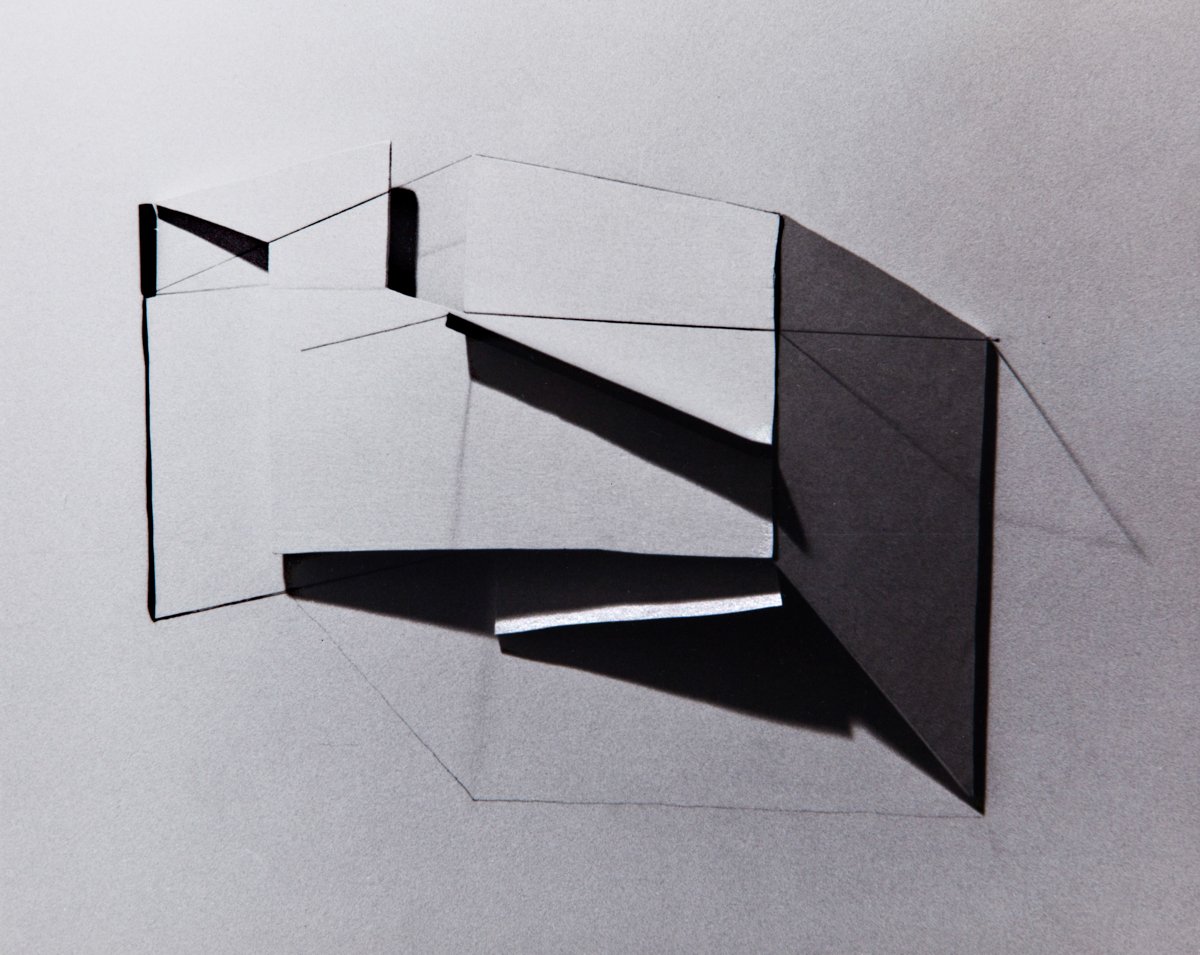

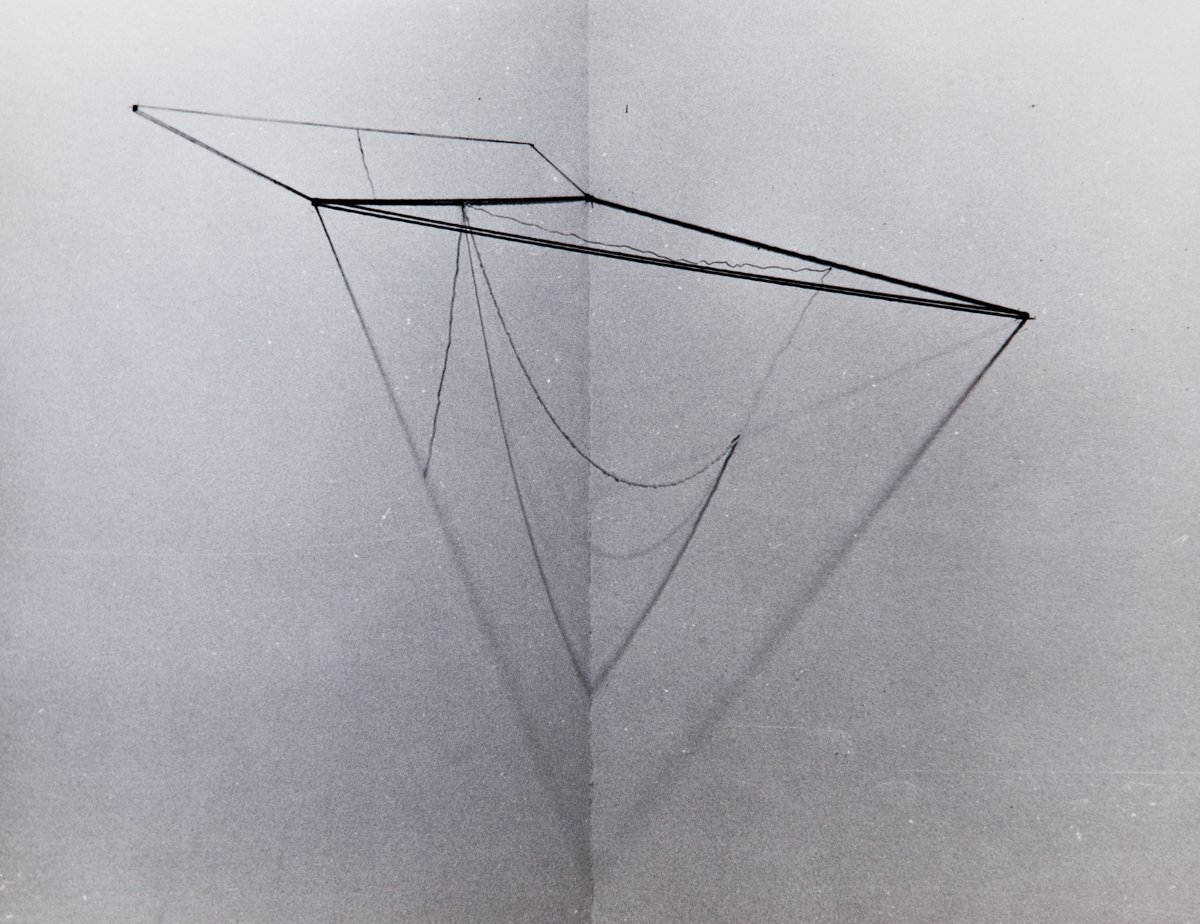

AP: I always drew as a kid, and as a young adult I moved to France, where I went to the École des Beaux-Arts. It was a different structure than American schools, focused on the model, and it didn’t really suit me. When I came back to the U.S. four years later I went to the San Francisco Art Institute, where I did my MFA in painting. Then I moved to New York and switched to geometric sculptures that create cast shadows. This body of work was well received, and in 1979 I was invited to be in a group show at the New Museum, “Dimensions Variable”. I’ve also done a lot of artist books, two of which are in the MoMA collection.

MH: Most artists don’t like to be labeled, but your work has the outward appearance of geometric abstraction. And yet there’s an atmospheric quality to the work, which keeps it from diving into pure abstraction. There’s also a landscape and architectural vibe in some of the pieces. The term “Atmospheric Abstraction” comes to mind. How do you regard your work?

AP: I like “Atmospheric Abstraction”! I feel that in many ways I’m a landscape painter. Living in the Hudson Valley, I’m very moved by nature. We’re kind of isolated, and the sky is fantastic – there’s this constant transition of light that I want to capture in my paintings. A lot of geometric abstraction is cold and sharp, but the landscape influence conveys an emotional quality that I like. There’s also potential for the inversion of geometric shapes, which engages perception and slows you down while you try to make visual sense of it. But in the overall painting I want to create a sensitive space that’s very vulnerable. In some ways I feel like I’m still a beginner, trying to shape my paintings into poetry.

MH: How did you find your way to abstract painting? Was it a long progression, or did you make conscious choices along the way about how you wanted to express yourself?

AP: I come from a bunch of different mediums and concepts, from painting surreal dreams to abstract sculpture, artist books, painting in watercolors, and working with round shapes. But with this last group of paintings, I’m finally coming to something. I’ve had more time to develop it and it’s a larger format, so I feel like it’s finally blossoming in an interesting way.

MH: Why squares and rectangles? Do they represent something to you? Is it a choice, a process of elimination? Why not circles and spheres?

AP: I’ve used circles and spheres a lot, and I want to go back to them because it’s very pleasurable working with those shapes. But I’m interested in creating an optical illusion, and it’s easier to do with squares and cubes and rectangles. The geometric shapes invert and go backwards and forwards in space, playing with perception.

MH: What I’m getting at in a roundabout way is a curiosity in the way that an artist chooses to express herself. Specifically, how do you know that what you’re painting, and the way that you’re painting it, is the right creative expression for you?

AP: Oh, each piece is a terrible struggle! It really is. I start out with a nice little sketch and then when I start painting it, everything goes wrong. It's a nightmare.

MH: Do you feel like you have to go through that process somehow? Is the struggle necessary?

AP: I’d rather not go through it, but it seems to be part of my process. I mean, just to show you how horrible it is, I’ll show you this piece I’m working on. I’ve painted over this so many times…

[She shows me a piece that was turned toward the wall. It’s beautiful.]

AP: I can’t see how I’m going to finish it. I always have to find my way out of a painting, but I can’t see my way out of this one. [Heavy sigh, slow shaking of head.] I have some ideas that I’ll try. I might be able to figure it out, but I never know. It’s so stressful.

MH: Would you consider this to be your painting style?

AP: It’s evolving. I feel like I have a way of moving the paint around that’s personal to me, but there are things that I could push further. Each painting is a different experience for me; each one is a mountain.

MH: I’m jealous of the artist who goes into her studio with utter confidence in what she’s doing, never doubting for a moment that she should be painting anything other than dog portraits, or seascapes, or whatever. Do you ever think about what else you could be doing?

AP: I believe that we have to find what we want and what’s important, and there’s no one who can tell you. That’s the goal, to find yourself, whatever it is that turns you on. The most special thing you can do is to embrace your disabilities. Maybe the thing that you do “wrong” is precious. Like, not knowing how to draw is fine, and you should embrace that.

MH: There’s this romantic idea that the artist doesn’t find her voice, the voice finds the artist. Like there’s some artistic concept floating out there, waiting for the right artist to come along and grab it. What do you think? Too woo-woo?

AP: Very woo-woo. But I think there are breakthrough ideas, brilliant ideas, that might fit that concept. James Turrell comes to mind. I think that sometimes you find things that are interesting and make them your own. You see something you can use and make your own recipe with it.

MH: I’ve been reading “Zen in the Art of Archery” by Eugen Herrigel, and it’s given me an interesting take on the creative process. In Zen, archery is not regarded as a sport, and hitting the bull’s eye is not the goal. Instead, training in archery is a method through which the student becomes totally immersed in the technique. While perfecting her outward technical skill with the bow and arrow, the archer comes into inner alignment with the process, eventually merging with it completely. I think this is also true for the artist. I wonder if you ever have experiences of this type. Do you ever have that sensation of merging with your medium?

AP: Yes, it’s really special when that happens. I wish it would happen more often. Sometimes you do something, and it comes out just right. It’s a kind of focus and centeredness, and maybe has something to do with not letting other things in your life interfere with your concentration. I also find that ambition isn’t good for my creative process. It took a long time for me to let go of that and become more committed to the painting.

MH: Herrigel speaks of archery as a medium which leads to a methodical immersion in oneself. I think we do this as artists, whether we’re aware of it or not. That moment after you’ve been painting for many hours, when you’re in auto-pilot mode, and then something sort of clicks. Suddenly you feel like the canvas is almost painting itself, like it has a life of its own and you’re just along for the ride. Do you ever experience this? How does it affect you?

AP: Yes, I do. After I’ve gone through the horrible struggle, I start to see where it’s going and how I can make it work, and then I begin to get really excited about it. That’s an important moment, when you know you’re going to make it and the painting starts to give you something back. It feels victorious in a way, a spiritual thing, like finding yourself in the painting, and then it can step away from you. It’s an amazing experience, the biggest thrill. But it’s hard! And it takes me a long time.

MH: In your artist statement you write, “I never know at the start how (the painting) will turn out. If I did, there would be no point in doing it.” I love that. It feels like an openness to discovery, and it seems like it must take a certain amount of trust in yourself that you’ll recognize “it” when it appears. How would you describe the moment of discovery?

AP: It’s a relief! Because when I start out, I think it’s going to be the most brilliant thing, and then I work on it and it’s awful. So when I get to the point where I actually like it, it’s wonderful. When the painting works, it gives you something back. When it’s not working, it’s a feeling of frustration and insecurity.

MH: Returning to “Zen in the Art of Archery”, there’s a passage that made me think of you. The author describes Zen as the immediate experience of that which cannot be apprehended by intellectual means; one knows it by not knowing it. Through many years of training, the archer learns to “know” through the medium of the bow and arrow. Is there a way that you begin to “know” as you paint? At some point in the process, is there an inclination or intuition that you’re coming closer to that elusive thing?

AP: Yes. It’s a magic moment. You transcend yourself, and that’s when the painting leaves you and has a life of its own. Maybe it’s the expression of your best self, of your sensitivity and your innate wisdom. It’s always a surprise, something that never existed before and there it is. After it’s finished, you look back and think, how did I do that?

MH: There are so many complexities to being an artist, and we all know that it’s a difficult path. There are many rewards, but there’s also a lot of aggravation, and we’re constantly coming up against internal and external obstacles, like self-doubt, or having to move out of your studio, and so on. But in spite of it all, we continue making art as though our lives depended on it. Do you have any insights into why artists are so driven?

AP: I think when you practice art for a while, you almost need to make work to feel okay. There’s something magic about making art. It’s because you overcome those obstacles that you find what it is that you need to find. I have to find it, and if it isn’t there, I’ll stay with that one painting until I do. And I never know how it will turn out – each time is different. But it’s very satisfying when you work it out, and the struggle is just something you have to go through.

MH: For those who plan to see your show “Inner Window” at the Garrison Art Center, is there anything that you’d like them to know about the work that’s not readily apparent?

AP: I feel like whatever people take away is fine. It’s about light and personality and warmth, and it’s pretty positive, given what’s going on in the world. I hope they can slow down to look and find something in it for themselves. It’s still a mystery for me.