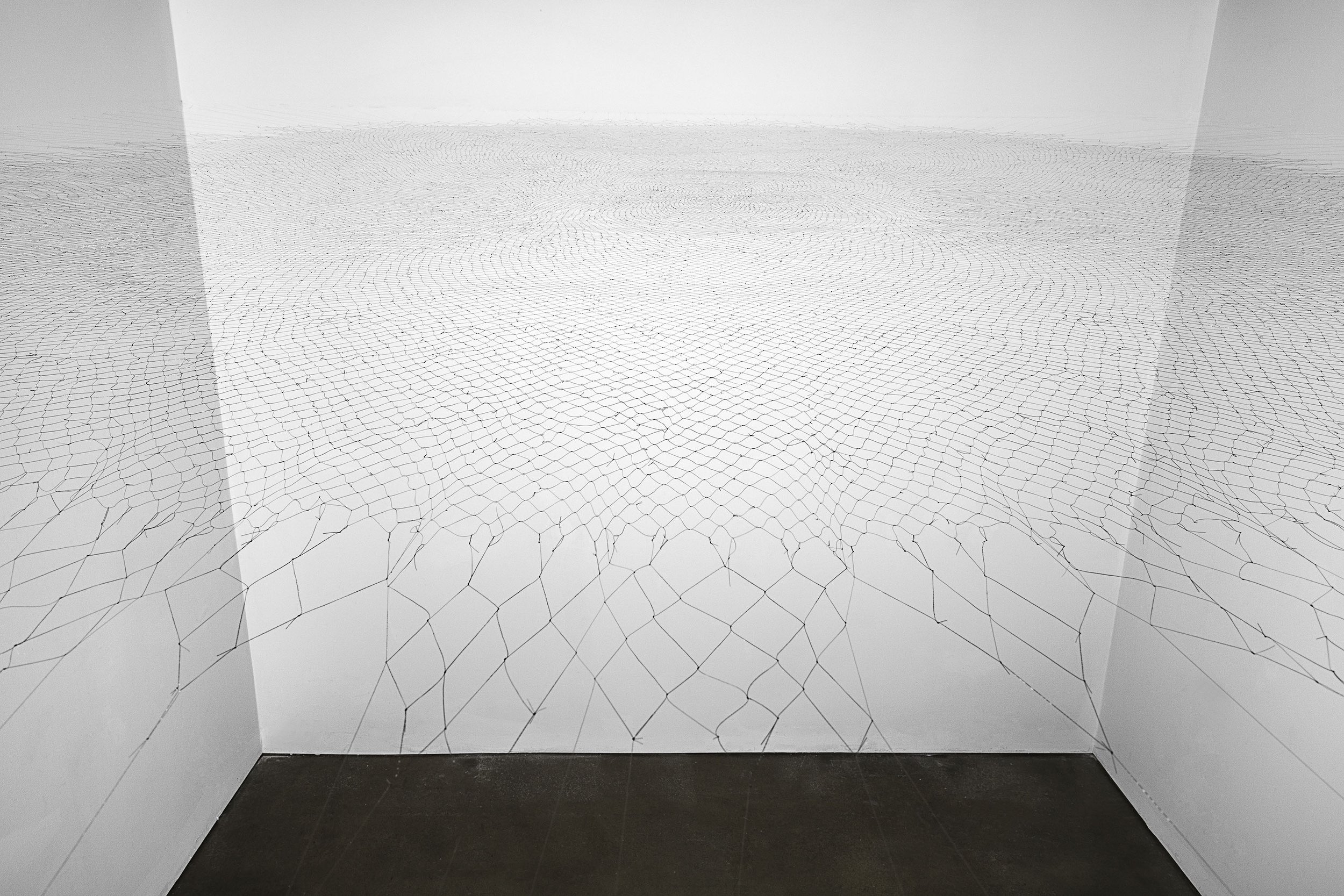

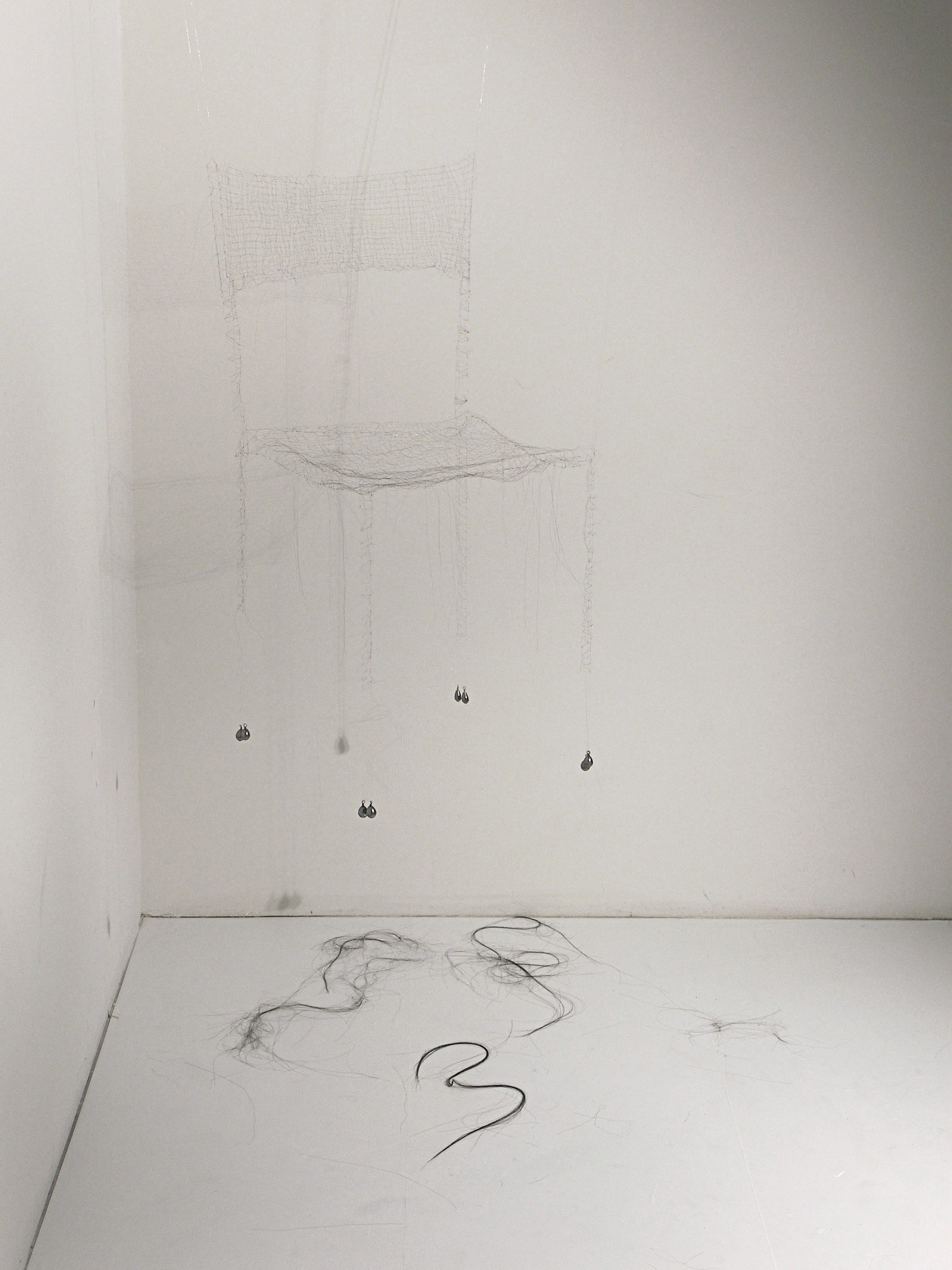

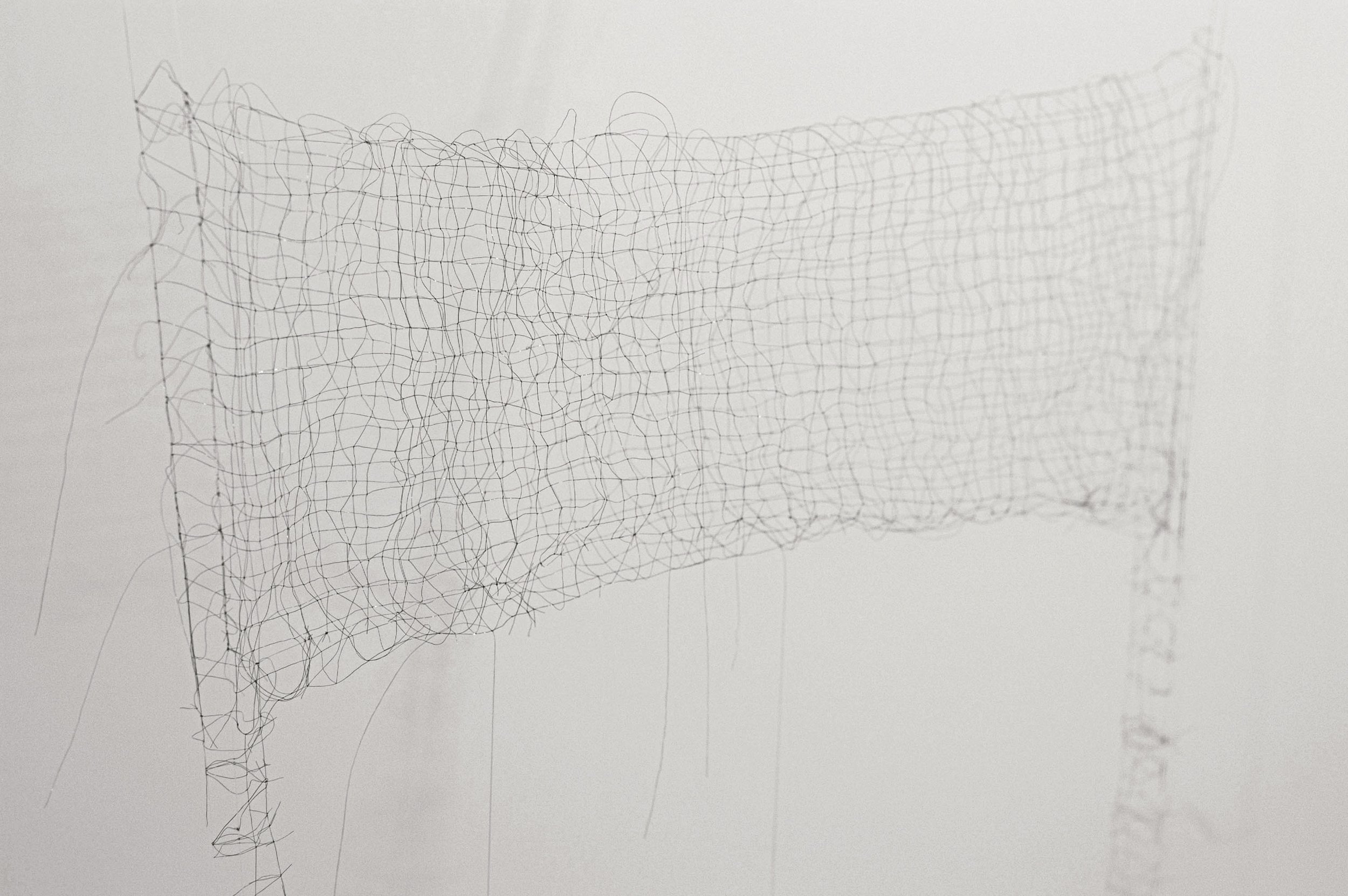

Jayoung Yoon is an interdisciplinary artist who uses her body to examine the nature of emptiness. In her current solo show at Garrison Art Center, Yoon creates two- and three-dimensional forms with her hair, weaving herself into the space and intimating an underlying connectivity. Indeed, when a slight draft sends a ripple across the translucent, shimmering forms, there’s the feeling that you’ve inadvertently stumbled into Indra’s net. The presence of the artist is felt in each knotted strand of hair, and we too become present as we consider the staggering amount of time and labor involved in her craft. The title of the show, “Sowing Seeds of Emptiness”, hints at the essence of Yoon’s work, which is an inquiry into the Buddhist philosophy of form and emptiness. She broaches the subject poetically, first by creating the sensation of emptiness, and then subtly posing the question, Empty of what? The topic of emptiness is dense, and many volumes of Buddhist philosophy have been written in the effort to arrive at its core. But where words fall short in conveying that which has no existence, Yoon’s sculptures are luminous veils that simultaneously reveal and conceal the answer to the paradox: Empty of a separate existence. By incorporating human hair with time, by weaving and knotting them together, Yoon suggests that the bliss of emptiness is experienced when we awaken to the interdependence of all things.

MH: Your show at Garrison Art Center is breathtaking and exquisitely beautiful. It’s hard to convey in words the presence that it carries when seen in person. When did you start working with hair as your medium, and how did the idea evolve?

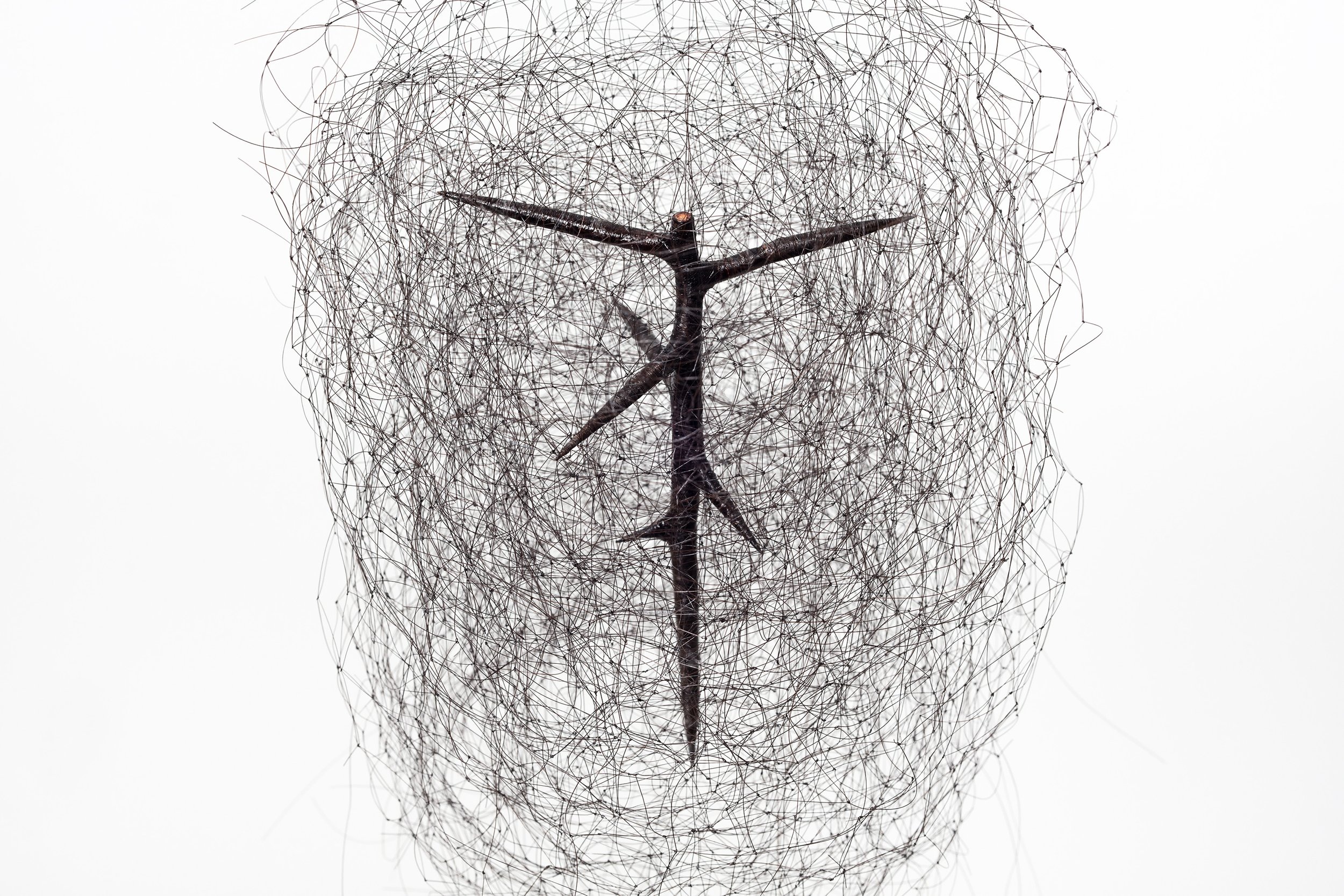

JY: I worked with thread when I was at the Maryland Institute College of Art, exploring how our physical or mental pain can transform into personal growth. I created a metaphorical space in an installation with thread and nails and empty space, like a cocoon space. After that I started to use my body to make videos, and then in 2007 I went to a fiber program at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, where I started to think about materiality and process as a medium for my work. I was looking for a material that could represent both body and mind. And since I had experimented a little with hair, using a single strand to make an almost transparent form, I thought that hair could represent a kind of ineffable thought. Hair as a material is very physical, and when people see it, they think of growth. But hair is also visceral, so it has these two distinct qualities that I thought worked well together.

MH: Are you inspired by the Korean craft of weaving horsehair? It seems similar, but weaving horsehair must be a different experience from knotting human hair.

JY: I think you’re referring to the Korean tradition of hat making that’s called gat. When I started using hair, I wasn’t aware of this tradition, and the technique is totally different from what I was doing. But I went to Korea in 2019 to learn traditional embroidery and patchwork (jogakbo) for my installation project “I Am the Emptiness” at Garrison Art Center. I learned hand-sewing techniques at the Korean Cultural Center, especially a triple-stitched seaming technique called gekki. While I was there, I saw a horsehair hat in one of the studio rooms. I was fascinated by its delicacy, and the transparent quality totally resonated with my artwork. I tried to find a workshop where I could learn gat, and I found out it only exists on Jeju Island, where there are a lot of horses.

MH: Would you talk a little about the harvesting of your hair? Is there a ritualistic aspect to cutting and growing it?

JY: When I started to completely shave my hair off, it wasn’t only that I needed the material, but also because I use my body for my video performances. The significance of cutting off my hair was around letting go of ego, as in the Buddhist tradition.

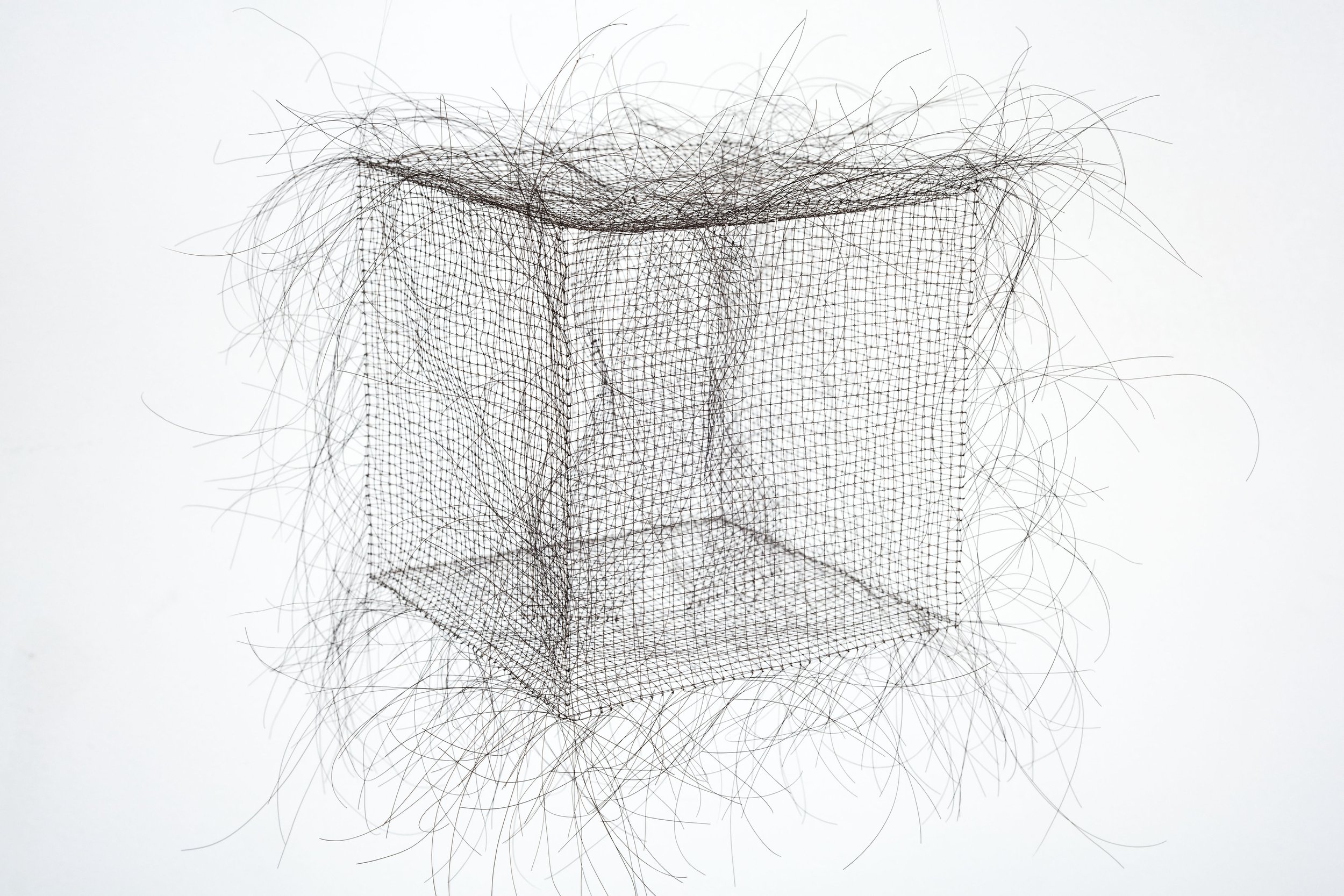

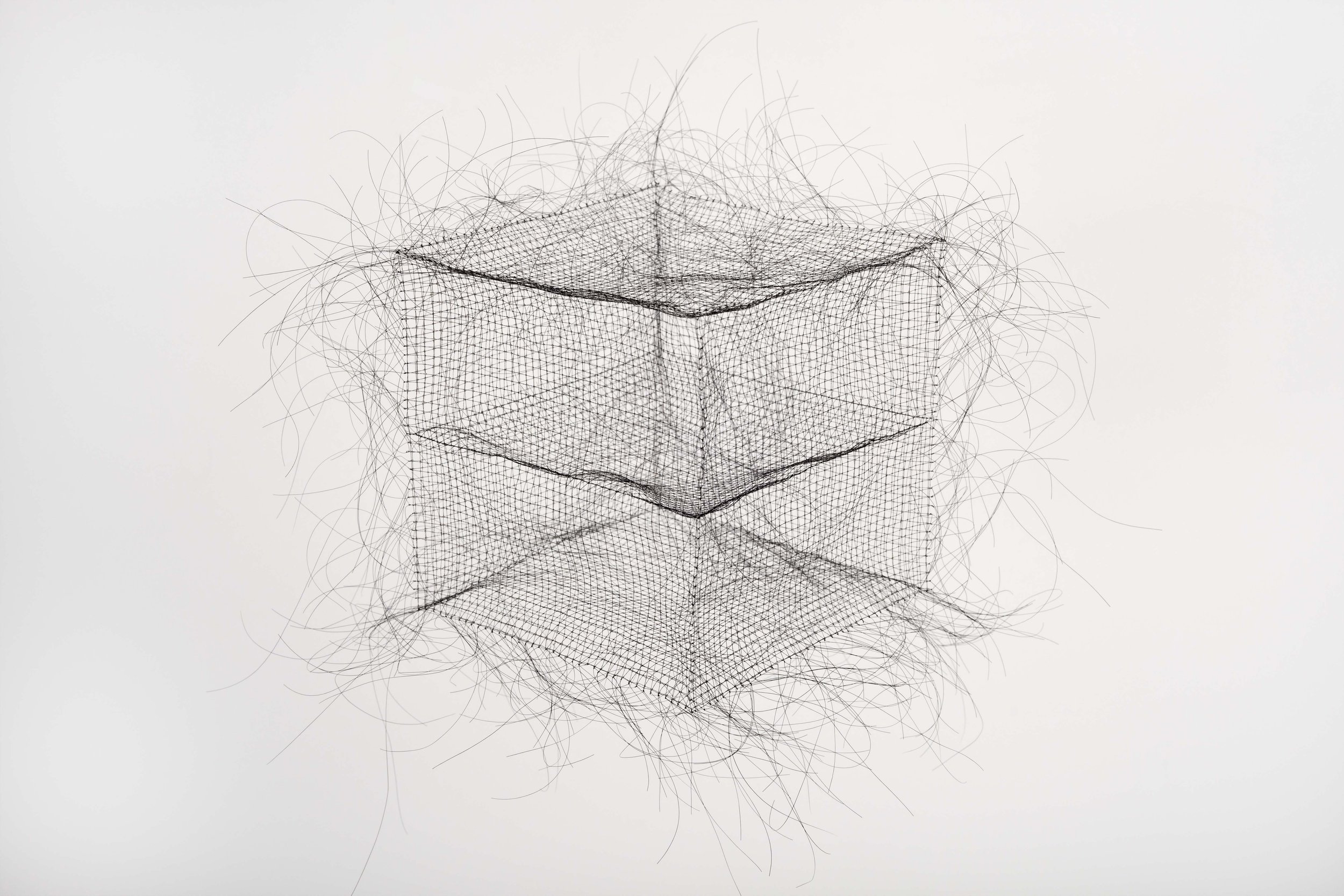

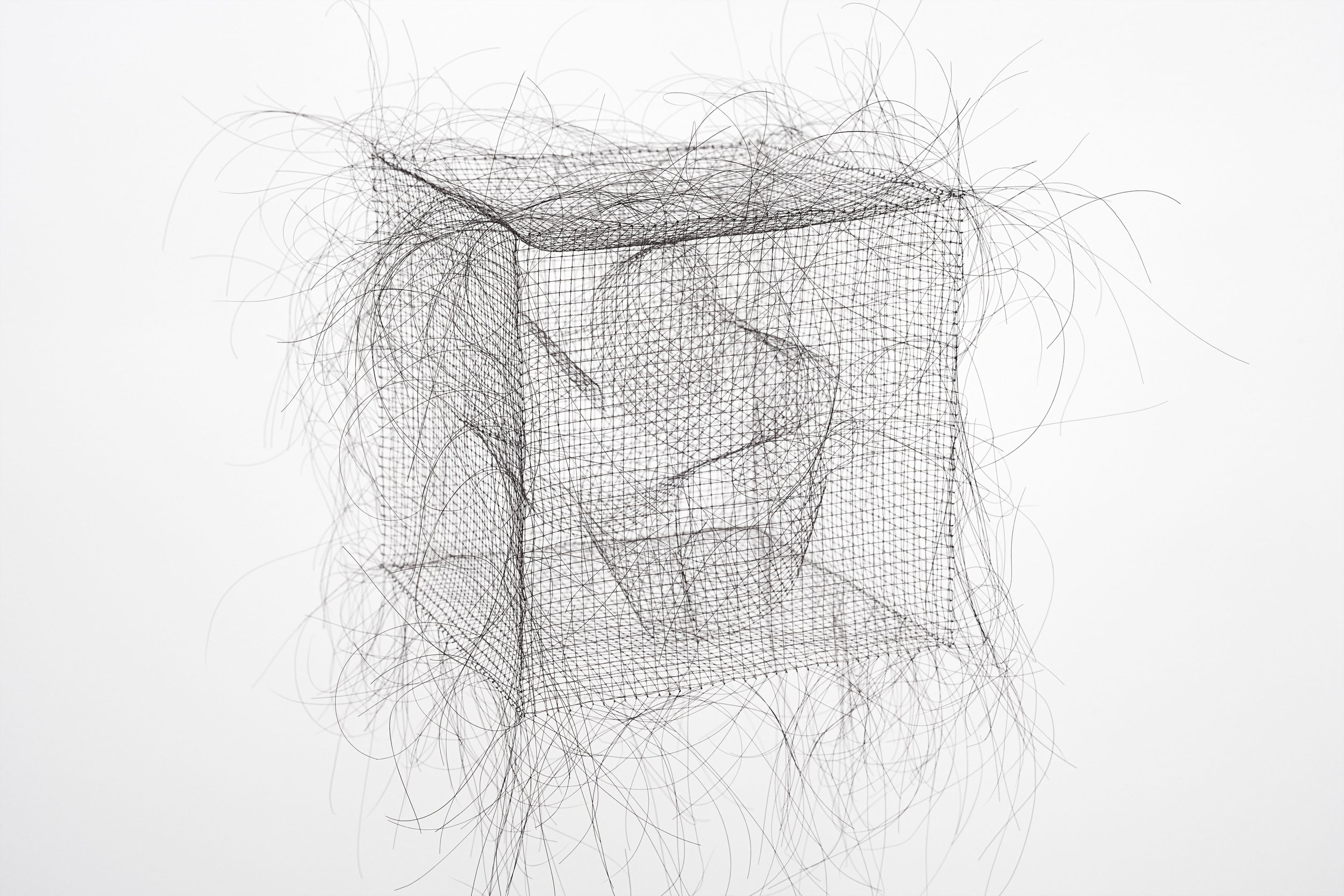

VIDEO: Form and Emptiness No. 14, 2017, artist's hair, glue, 8 x 8 x 8 in.

MH: Is there anything about your process that you’d like to share? I’m at a loss to even come up with a question about it, so feel free to elaborate.

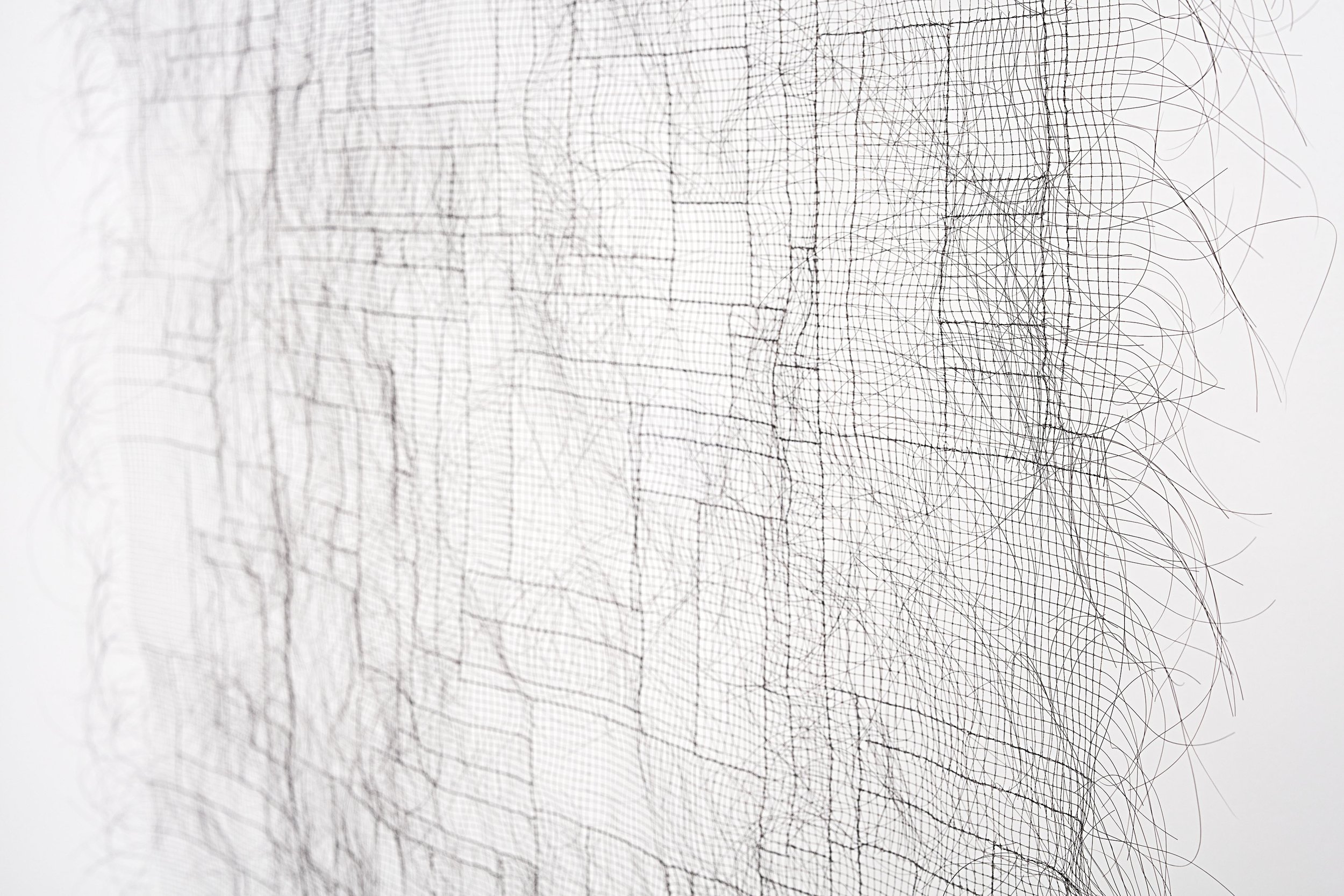

JY: In the process of making the semi-transparent forms for my “Form and Emptiness” series, I work with spacing, like making simple fishing nets. I make a handmade loom and stretch each strand of hair, then I use a needle to weave the hair in. I need to find the right tension, because if I stretch it too tight the hair snaps, but if it’s too loose the hair curves. I tighten them one by one, and then I use glue to bind them together. I make six panels and tie them together to make cubes. It’s a very labor-intensive, time-consuming process and it requires focus and patience. I need to be present, so I can’t watch anything, but sometimes I can listen to podcasts. Recently I’ve been listening to podcasts of how to become a good parent.

MH and JY: Hahahaha!

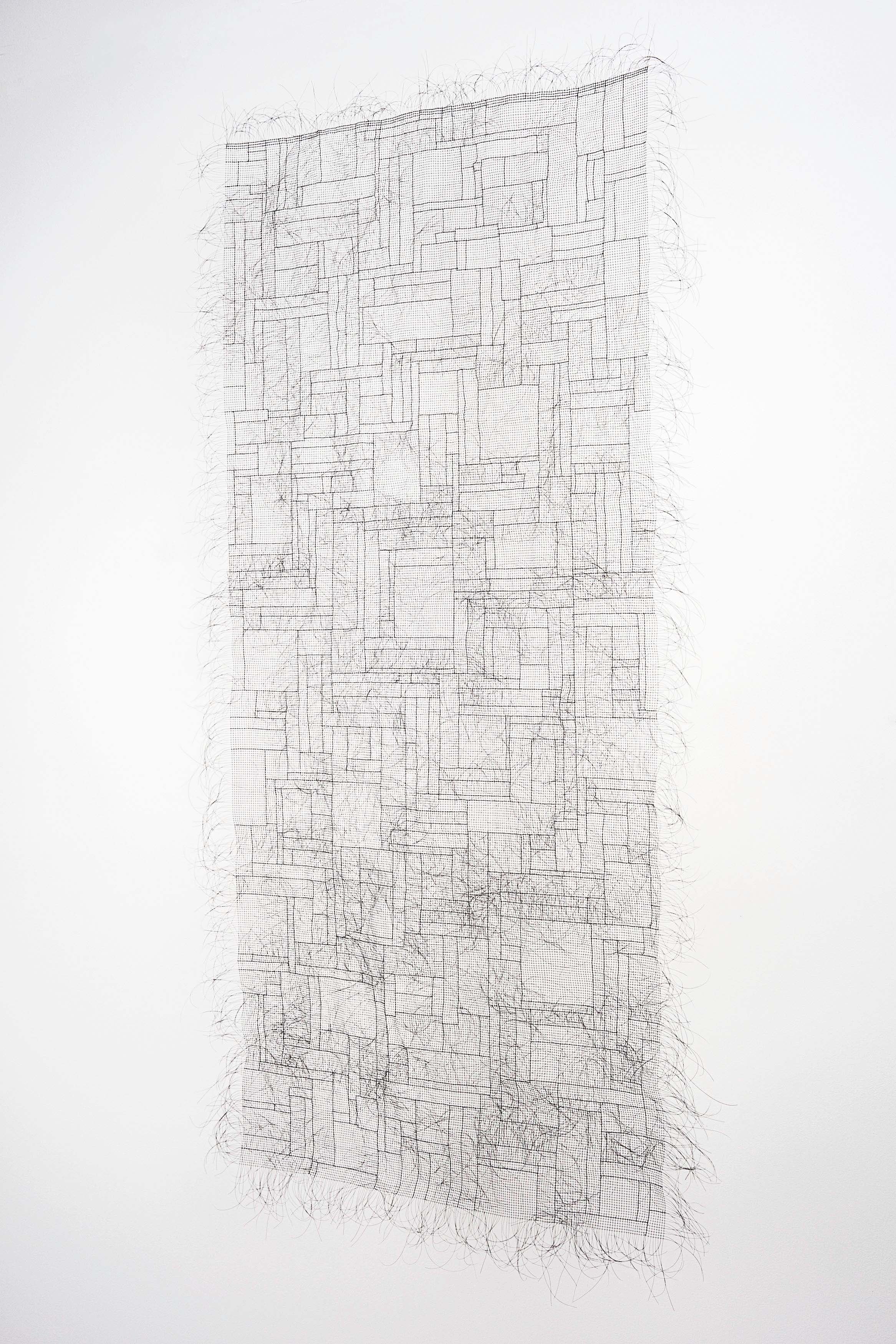

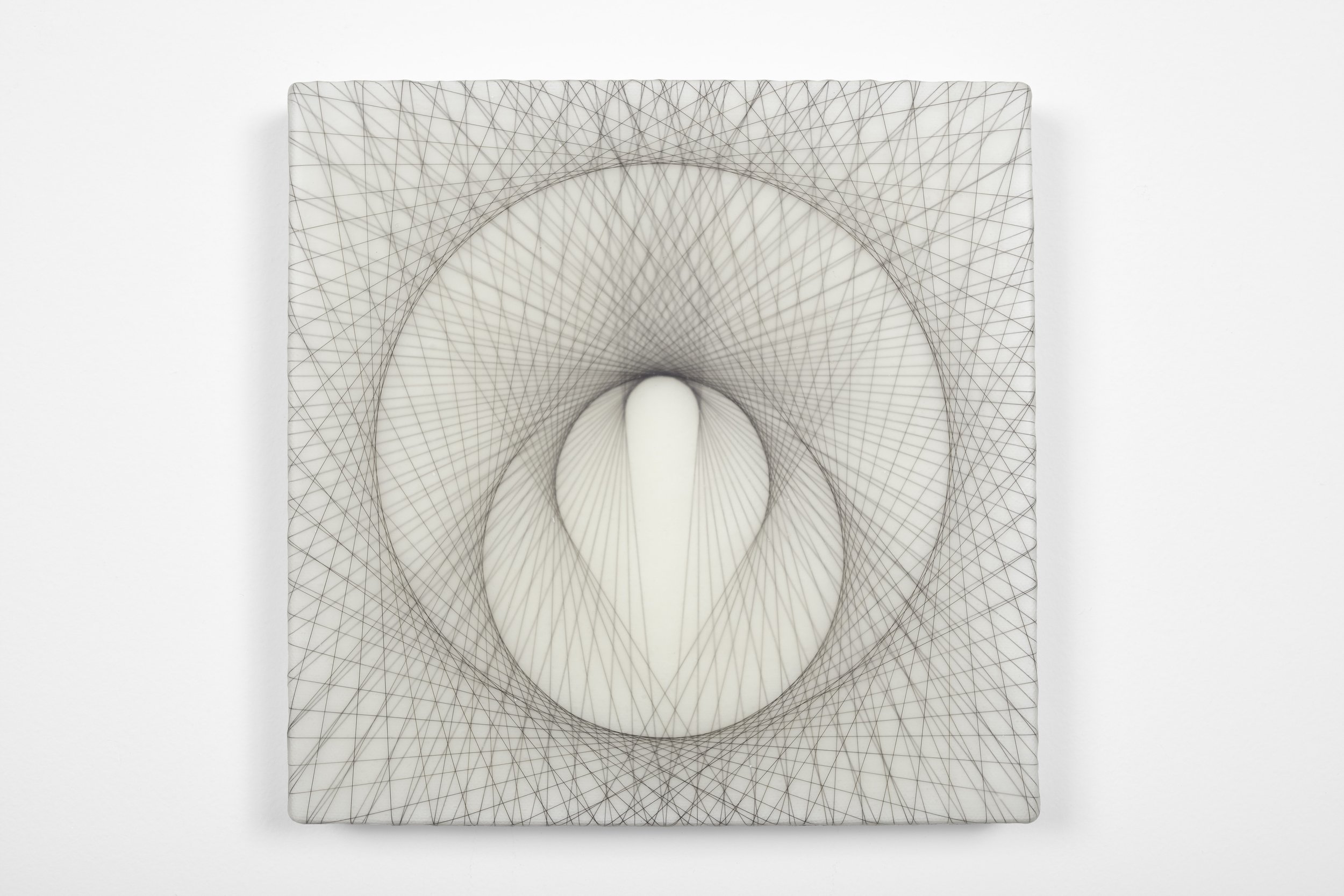

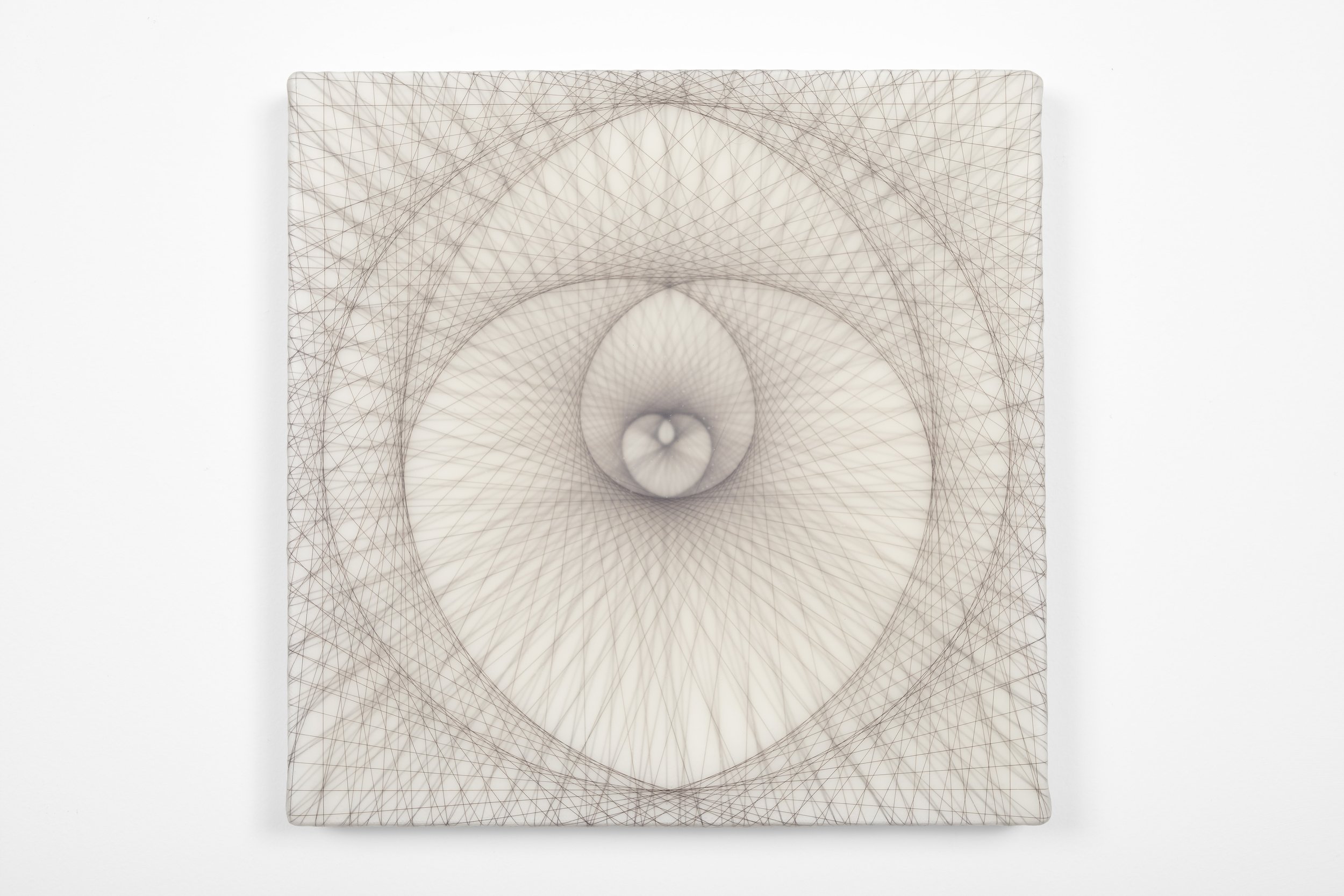

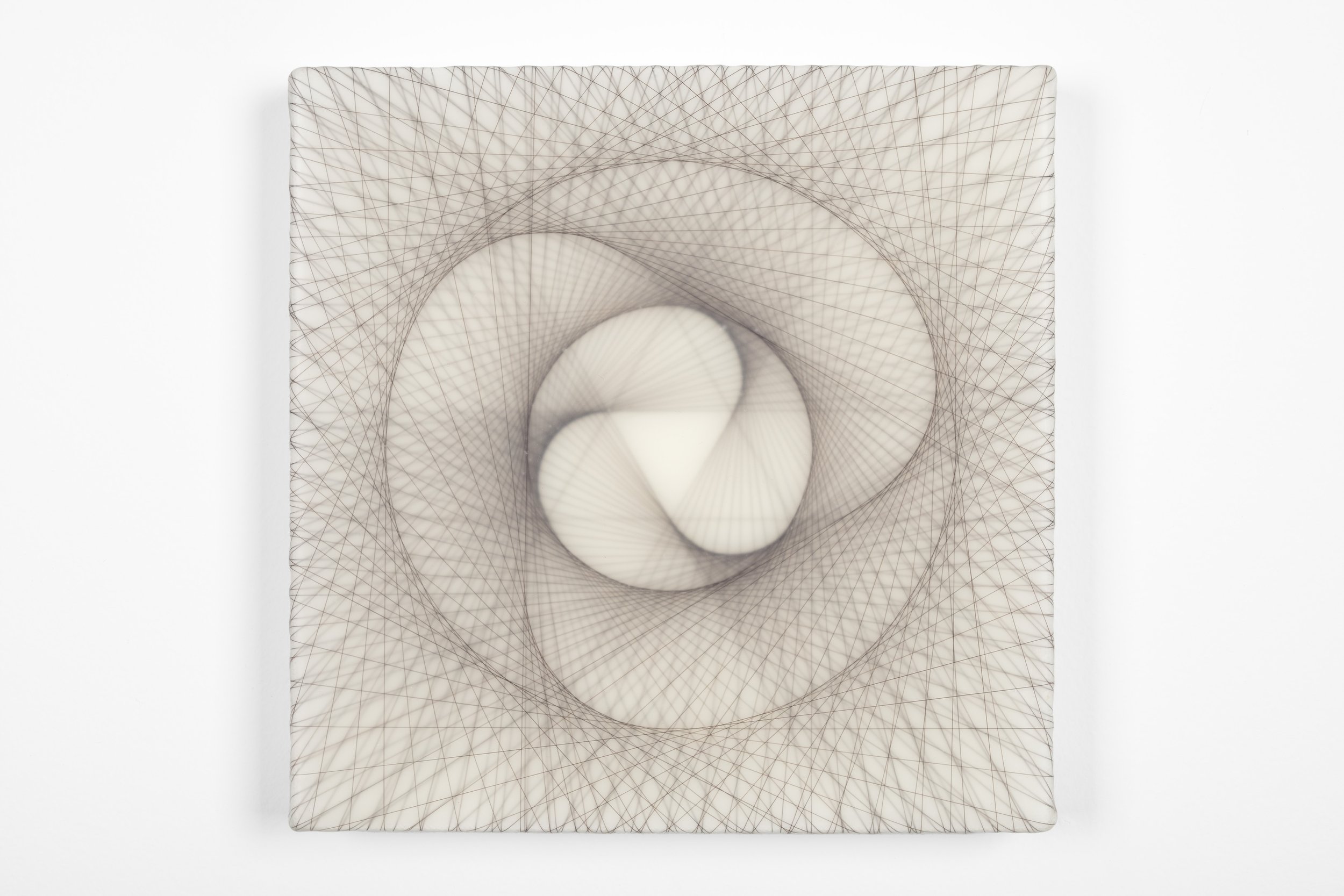

JY: In the two-dimensional works, I come up with a geometrical sketch using the Fibonacci sequence. Then I put my sketch in Illustrator, print it out, and decide how many layers I want to go with. Then I cut the papers, place them on a canvas panel, and cover the lines with hair. I refer to patterns from Islam and books on nature, sometimes flowers and seashells, which have the Fibonacci sequence.

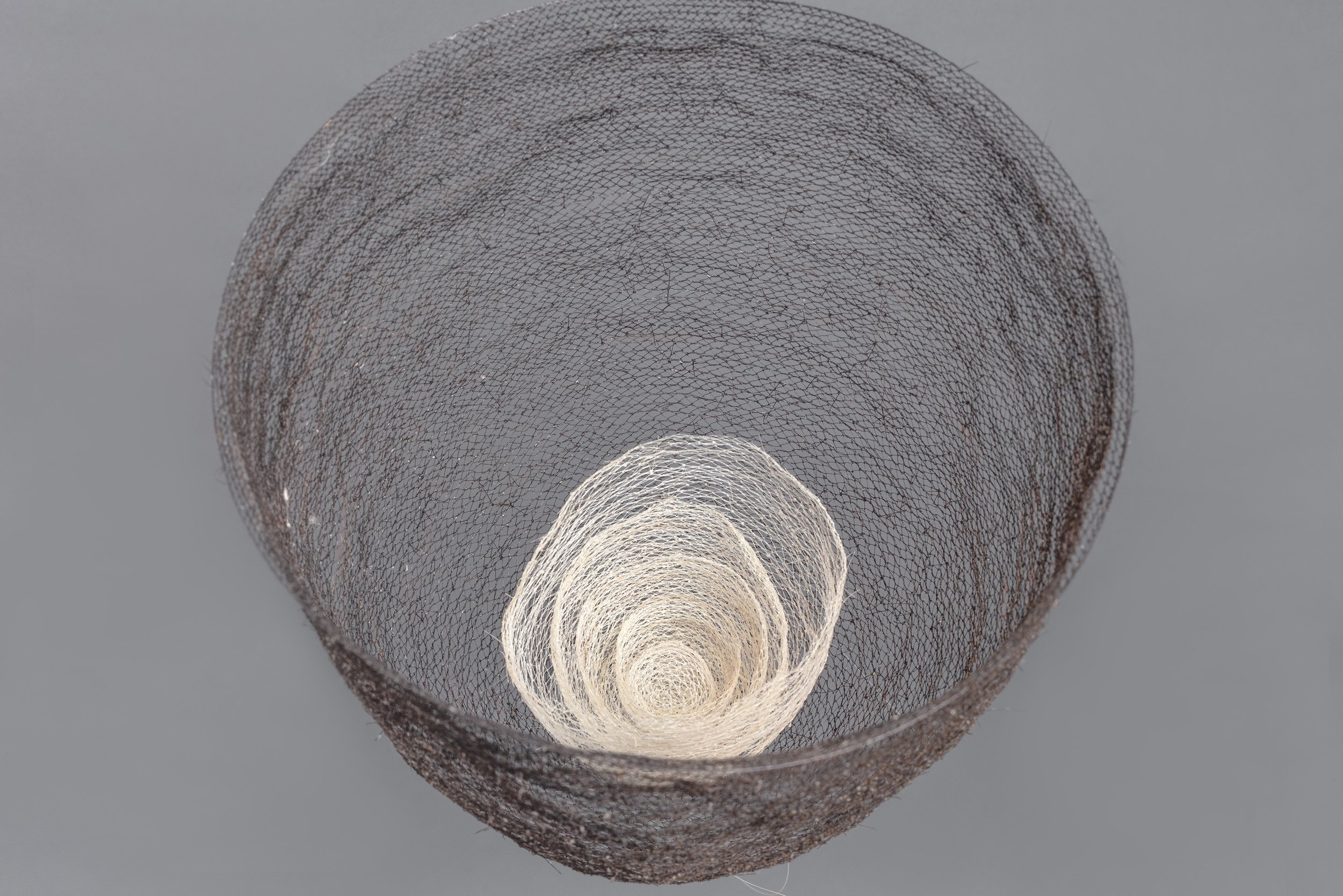

MH: In one of the pieces in the show, you used your black hair to create a bowl, inside which is another, smaller bowl made from the gray hair of your mother. The beauty and intimacy of this piece is almost painful, but you describe it as playful and funny, trying to convince your mother to let you clip some of her hair. Can you talk about this piece, and what it means to you?

JY: My mom came to the U.S. in August for a month to help babysit so I could have my studio time to prepare for my GAC show. That was already planned a year ago, so I asked her to collect her gray hair that naturally falls out whenever she takes a shower, and she brought a bag of gray hair with her. But it wasn’t enough to make several small vessels for my artwork, so I asked if I could clip some of her hair so I could finish the work. She was willing, but also very wary of where I cut, so she asked me to collect it from all different places on her head, so her hair didn’t look funny.

I’d like to talk about my mom a little bit because she’s a big influence for me. My mom is an artist, a Korean traditional dancer and musician, and she’s also a therapist. She often danced for people who have deep personal and social pain. For example, there are Korean comfort women who were abused by Japanese soldiers during World War II. I remember when I was young, she danced for those women, and at the end of her performance she invited all of them to come to the stage and dance with her, and I saw that the women were crying. When I saw that I realized that sometimes people heal through the physicality of the present moment; sometimes words cannot solve their problems. My mother is a very spiritual person, and she introduced me to so many books that inspired me. Her compassion and wisdom nurtures me as an artist and the person who I am, so I made this piece about my mom to show that she is a pearl of wisdom in me. But then after I made the piece, I thought about how the mother always embraces the child, and then when the mother gets old, the daughter embraces the mother. Those were some of my thoughts around the piece.

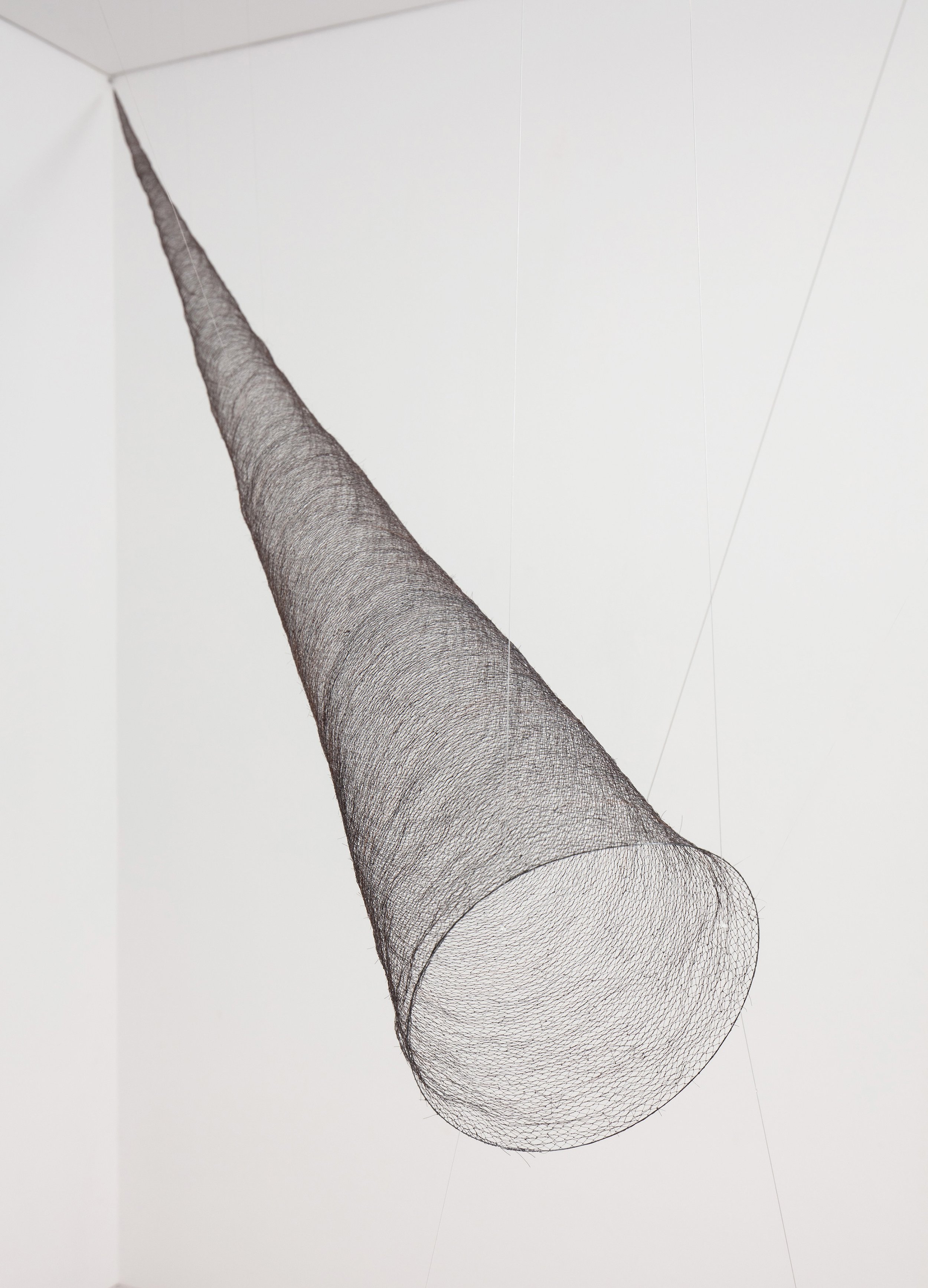

MH: In another piece, there is a long, tapered cylinder that looks like a transcendent trumpet, descending to the human realm to reveal some cryptic message. What significance does this piece have for you?

JY: The title of this piece is “The Portal”. It was inspired by an experience that I had on a meditation retreat in 2005 in South Korea. There were practices around seeing the world as it is, cleansing our thoughts, and being present in the moment. In one of the practices, we were taught to keep questioning, keep searching beyond notions and knowledge, prejudice and judgment, and ask, what is beyond all that? During that practice, I had the experience that I disappeared as a person and became one with pure love and consciousness. So “The Portal” represents a portal into different dimensions. The sculpture has a vanishing point, and I installed it so people can look up into it and experience their stream of thoughts, and wonder what’s beyond the vanishing point.

MH: What is beyond the vanishing point?

JY: A sense of oneness, infinite being, and pure, unconditional love.

MH: One of the most astonishing aspects of your work is the apparent time that it takes to create each piece. It’s like you’re making time visible to us, knot by knot. Do you regard time as a medium in your work?

JY: Absolutely. I want people to see my work as an accumulation of single, present moments, instead of time as a linear past, present, and future. And because it’s such a labor-intensive process, people see and experience time in my work. This is a quote from “The Power of Now” by Eckhart Tolle:

“Nothing has happened in the past; it happened in the Now.

Nothing will ever happen in the future; it will happen in the Now.”

MH: I experience deep compassion in your work, and I think it’s because you’re using your hair. If you did the same work, substituting black thread for hair, there wouldn’t be the same feeling of generosity, of giving of yourself. Is there a sense that by relinquishing this vital part of your body, you’re emptying your own bowl, as it were, and filling up the bowl of the viewer?

JY: It’s an interesting point of view. Sometimes when I cut my hair for a video performance it’s completely shaved, and that takes a lot of physical endurance. I read that during the Tang dynasty, which was about 600-900 A.C. in China, there was a Buddhist nun who cut off her hair and embroidered an image of the Buddha with her hair on silk fabric to demonstrate her devotion. When I read that story, it really resonated with me. So your observation is correct – I give of myself to make the works.

MH: There must have been a huge shift when you switched from thread to using your hair.

JY: Yes, it was a big leap.

MH: It became more about giving of yourself, because you started using a piece of your body. You’re not cutting off your arm, but you’re still giving of yourself, both the hair and the time that it takes to manipulate it. So I have to ask, why do you do this?

JY: I cut off my hair and use it in my work so I can share my beliefs with people. Compassion comes from the knowledge that we all are connected, and we aren’t separate from each other. I think that’s why you see compassion in my work. Not just because I use hair, but also the visual forms that I choose, you can see the compassion there too.

MH: Does gender identity come into play for you? Hair is such an essential part of femininity, and I wonder if your work and your life make a statement about what it is to be a woman who is hirsute one day and hairless the next. Was there a feeling of liberation or loss when you first started cutting your hair?

JY: Actually, I don’t want my work to represent feminism or femininity at all. In the videos I try to give my body an androgynous appearance by completely removing my clothing and facing away from the camera while I shave my hair off. I want to be seen as a human being instead of representing gender or identity.

MH: Is loss a necessary component of your process? Do you feel that to execute the work authentically, you need to sacrifice something deeply personal and corporeal, like your hair?

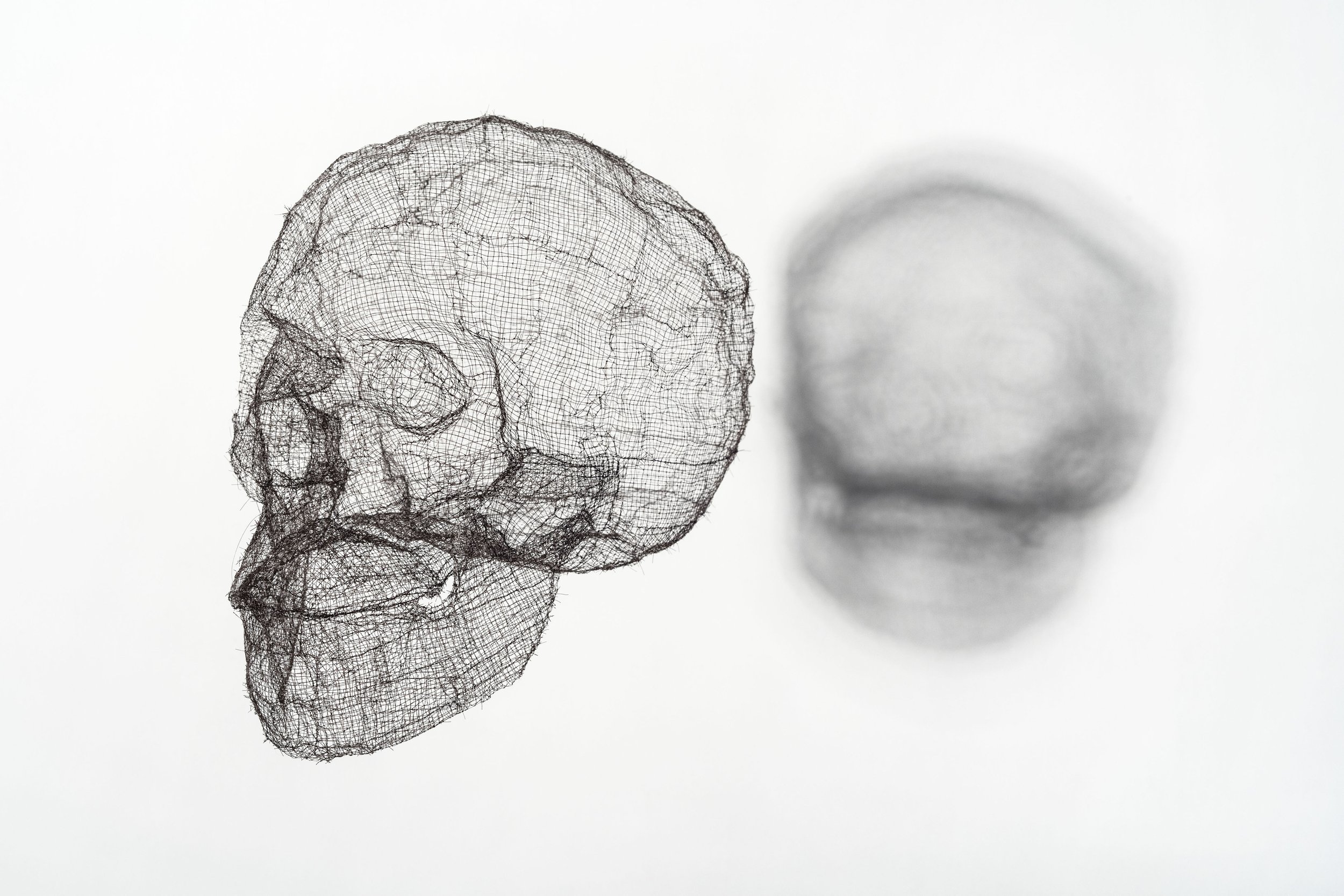

JY: My work is about the process, and because the hair comes from my body, it can represent loss or death. But then I use the hair to make sculpture and painting, so it gets new life. And then the hair sculptures sometimes get attached to my body again for a performance, so it’s a cycle of life and death.

MH: The word “empty” comes up often in your work. The title of the Garrison show is “Sowing Seeds of Emptiness”, which implies that emptiness is something that we need to plant, cultivate, and harvest. In other words, it requires our attention. How do you think about emptiness, and how do you wish to portray it in your work?

JY: I want to quote Thich Nhat Hanh, who explained the concept of emptiness:

“Without a cloud, there will be no rain; without rain, the trees cannot grow; and without trees, we cannot make paper. The cloud is essential for the paper to exist. […] They are empty of a separate self.”

(from “The Fullness of Emptiness” )

So in Buddhism emptiness doesn’t mean nothing, it means that nothing has an inherent existence. Emptiness indicates the interrelatedness of all things; we cannot separate ourselves from all the other processes on which we depend. In my series “Form and Emptiness”, there is a structure in the center of the cube, and every angle of the sculpture is slightly different. I wanted to suggest that our perception cannot be in isolation; it keeps changing depending upon the environment or different angles. It’s said that our thoughts and mind can change the world, and that’s based on the teaching that nothing is separate from myself. So if I change my mind, eventually that can affect the rest of the world. It’s part of the awareness of our interconnectedness.

MH: Knotting your hair into a kind of net is related to that. There’s a myth – I forget what it’s called – that says we all exist in a net that stretches to infinity, so a movement or event in any part of the net can be felt throughout.

JY: Indra’s net.

MH: Oh right! Or the internet. So basically, the way that you think about emptiness is not as a void, but as an interconnectedness. But I also think of the emptiness of ego, because that’s the big problem with ego: it thinks it’s separate.

JY: Yes.

MH: As a person who’s keenly interested in emptiness, do you experience dissonance between the ambition (emptiness) and the path that leads to it (striving)? Is there no way to arrive at emptiness except through the struggle of human experience?

JY: This is a difficult question. For me, the path that leads to emptiness is the one in which we see each form of human experience as it is and have total awareness that everything is interconnected. It reminds me of Vipassana meditation practice, which begins with awareness of breath, then awareness of body sensations, feeling a sensation arise and disappear. They explain that this practice is very important because our nervous systems are related to our body sensations. For example, there is some sound that I don’t like, and when I recognize it, I start keeping preferences, and the sound starts to cause me pain. Because once we don’t like something, there is the sensation of pain. So sensation is an important link between the outside world and our reactions. In answer to your question, I think it’s important to recognize the sensations of human experience, but to be able to reach emptiness we have to observe it as it is rather than react to it. We also need to recognize that the reaction comes up, and then goes away – it’s constantly changing, so we don’t have to react immediately.

MH: It’s a difficult question because we’re humans and we’re having human experiences. We don’t have the experience of a frog. To arrive at what you’re describing, the state of non-attachment, is very difficult, but I guess if you stick with it, sooner or later you’ll arrive at emptiness. But having the ambition to arrive at emptiness is an ambition, which compounds the difficulty. Do you ever struggle with this, or do you have it under control?

JY: (Hahahahaha!) Actually, the title of the show is “Sowing Seeds of Emptiness”, but I’m raising two young boys, and everything is not so easy. When I was preparing for the show, I wasn’t in any kind of peaceful state, and I was thinking that I’m in no position to talk about emptiness! So yes, I’m struggling with all of it.

MH: I know this isn’t fair to spring on you, but can you describe emptiness without saying what it isn’t?

JY: If I tried to define emptiness, I’d probably just repeat something that the masters have said. In the quote above by Thich Nhat Hahn, when he sees the sheet of paper, he sees that everything is in it. Emptiness is full of everything. It’s only empty of a separate self.

MH: One question about your series of 2D works on panel. The title is “Empty Void”, and I probably gave this too much thought, but…empty of what? By definition a void is already empty, so when we speak of emptiness, and when the tomes of Buddhist writings point to emptiness, what are they referring to?

JY: I understand that some people think that the title is redundant, since emptiness is already a void. But for me the void is the universe, and emptiness is the absence of a separate self. I want to talk about a video performance from 2009 called “Listening to the Mind”. It was the one video performance that I staged outdoors in an open space. I installed a hair sculpture and connected it to my ear and laid down on the ground for ten hours straight. I felt the temperature changing, the subtle movements of the hair sculpture in my ear, and the wind blowing over my naked body. I had the experience of my body disappearing into the universe and becoming whole with nature. It was a transformative experience, and I didn’t know about meditation at that time. I think the performance led me to explore meditation practices. I thought about creating images about my experience, which led to the sacred geometry and mandalas, so the “Empty Void” series represents the interconnectedness and oneness of everything.

MH: Were you uncomfortable during the performance? It must have been cold.

JY: If I kept clinging to the pain and thinking about how I didn’t like it, the pain and cold were stronger. When I was in the present moment, I was aware of the physical pain and temperature, but it didn’t bother me as much. The awareness made it bearable.

MH: I see your sculptures as shimmering veils that both reveal and conceal emptiness. It’s like they let us know that emptiness is present, then let us figure the rest out. But it’s a specific kind of emptiness – the emptiness of the human experience. By incorporating human hair with time, by weaving and knotting them together, you expose the frailty of existence. We are as ephemeral as your sculptures, fleeting forms in a sea of emptiness. Is this a valid interpretation of your work?

JY: Yes, I think that’s a good interpretation. In my studio I experience the sculptures as sometimes visible, sometimes invisible and fleeting. The visibility changes a lot with the environment. There’s a large piece in the GAC show that hangs near the window, and a lot of people don’t see it because it can disappear, depending on the time of day.

MH: It’s a tall order for an artist to express emptiness, given the density of the subject. Volumes have been written to describe the indescribable, and visual art often becomes bogged down in its medium and execution. Your works are transparent, luminous, and seemingly weightless, and I can think of no better way to approach the subject of emptiness.

JY: Thank you. My hair in both the embroidery and sculpture is semi-transparent, so instead of blocking peoples’ view, the viewers can see each other through the sculptures. Through careful placement, the installation can integrate with the audience to create the feeling of interrelatedness. So there’s the potential for the viewer to move through the experience, and the gallery becomes an intimate and contemplative space.

MH: I think that’s true. There’s also the moment of astonishment when the viewer realizes that the material is your hair, that you tied each knot by hand, and in that moment, we experience the presence of the artist. And it does have the effect of bringing one into the present.

JY: My hope is that the viewer will discover a new perception and develop their awareness of the moment.

MH: Is there anything else about your work that you’d like people to know?

JY: I’ve been reading about how environmental destruction, climate change, and deforestation disrupts the global ecosystem, causing viruses like Covid to spread to humans. And it will likely become more common if we aren’t aware that humans, animals, and the environment are interconnected. In quantum physics, the act of observation changes that which is being observed, just like our thoughts create our own reality. So I think of my art as a manifestation of my mind and thoughts which can influence others in a positive way, and change the world. In my videos and performances, I often try to visualize cleansing my thoughts, not only personal memories but also collective memories through the meditative process.

MH: What’s the best part about being an artist?

JY: For me being an artist is trying to remember who I really am. Spirituality is about remembering who we are, which is pure love, pure consciousness, and infinite being. I search for answers, I create my work, and then I share my effort, rather than keep it to myself. And I share all of this through my visual art.