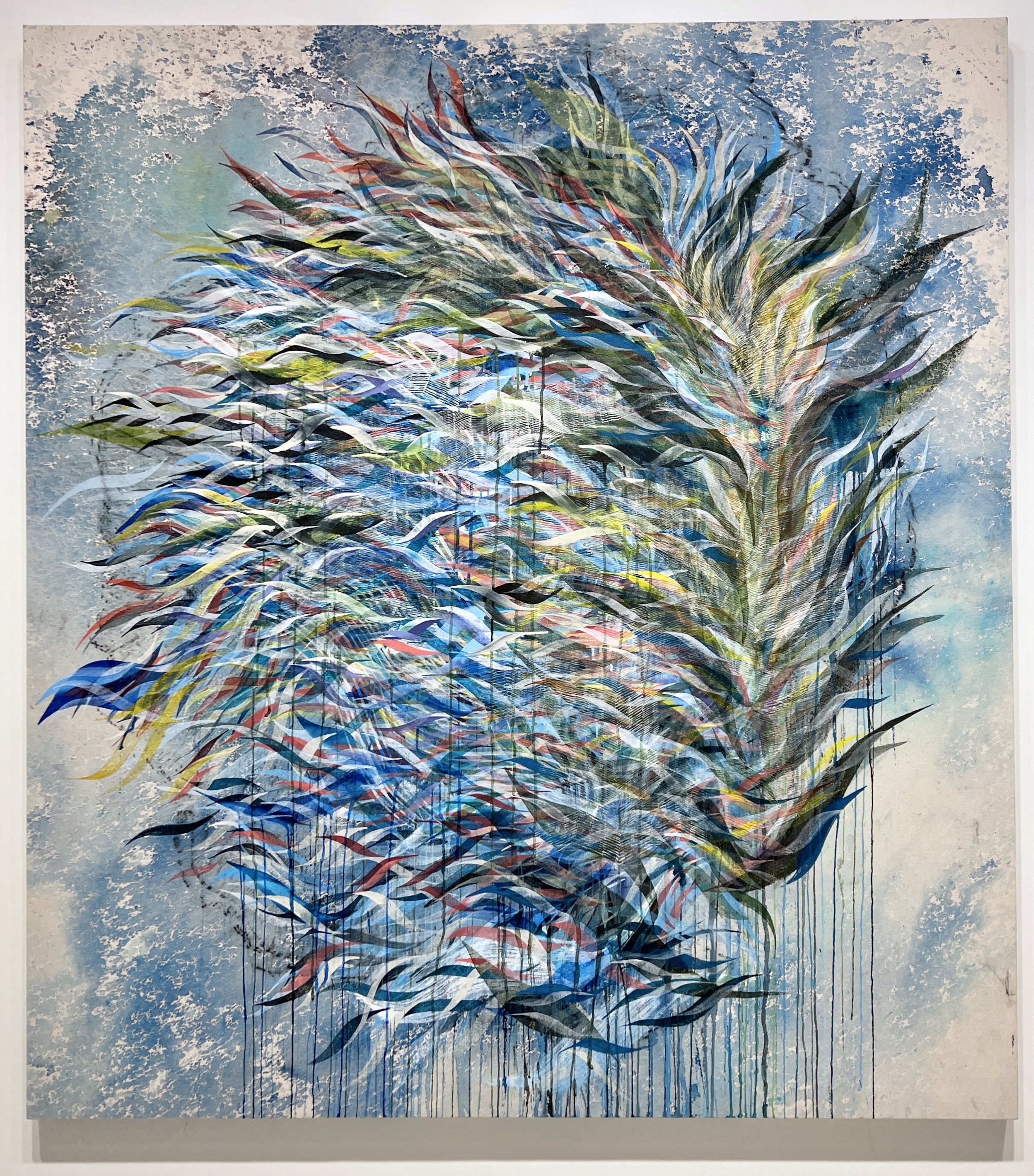

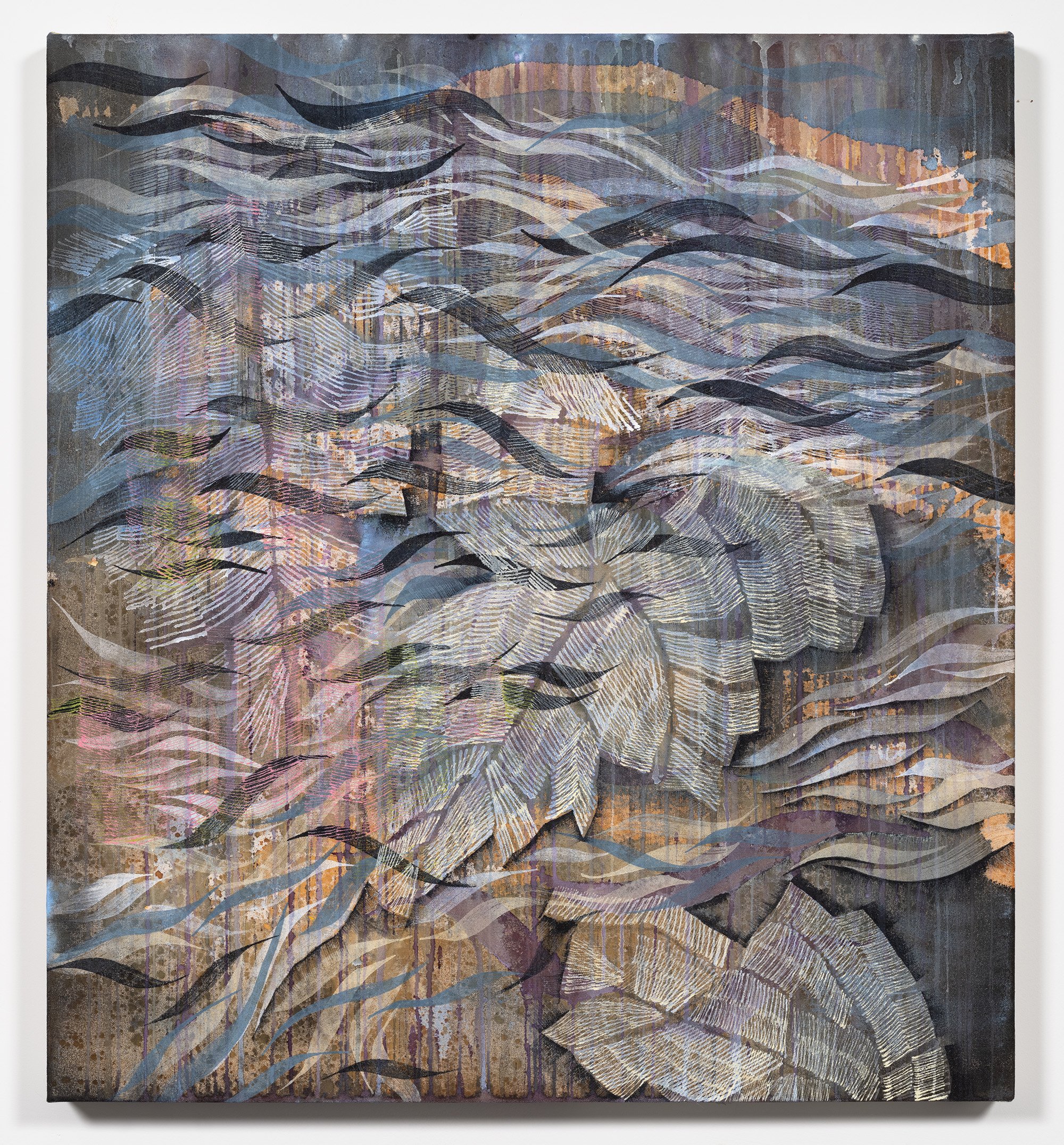

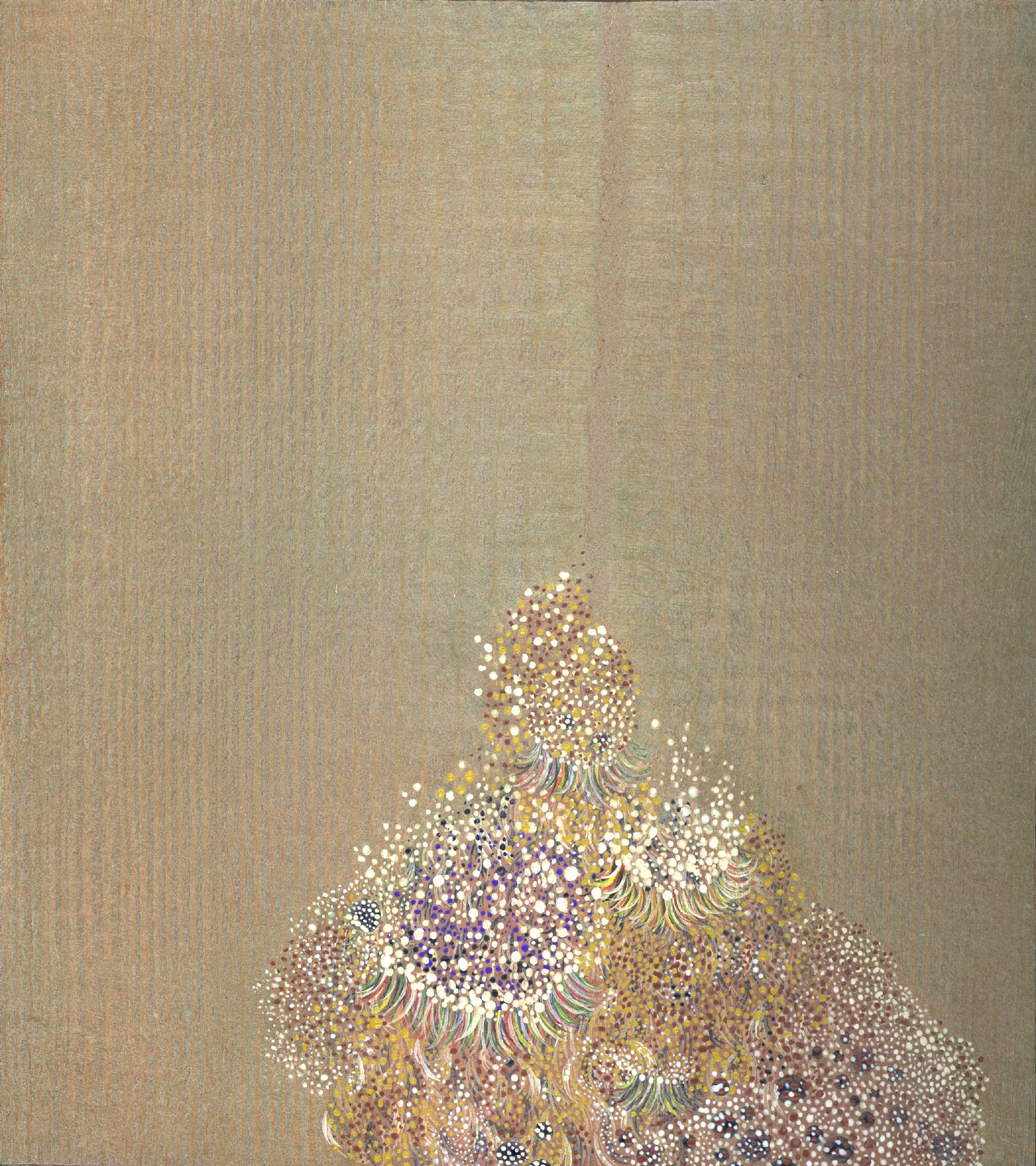

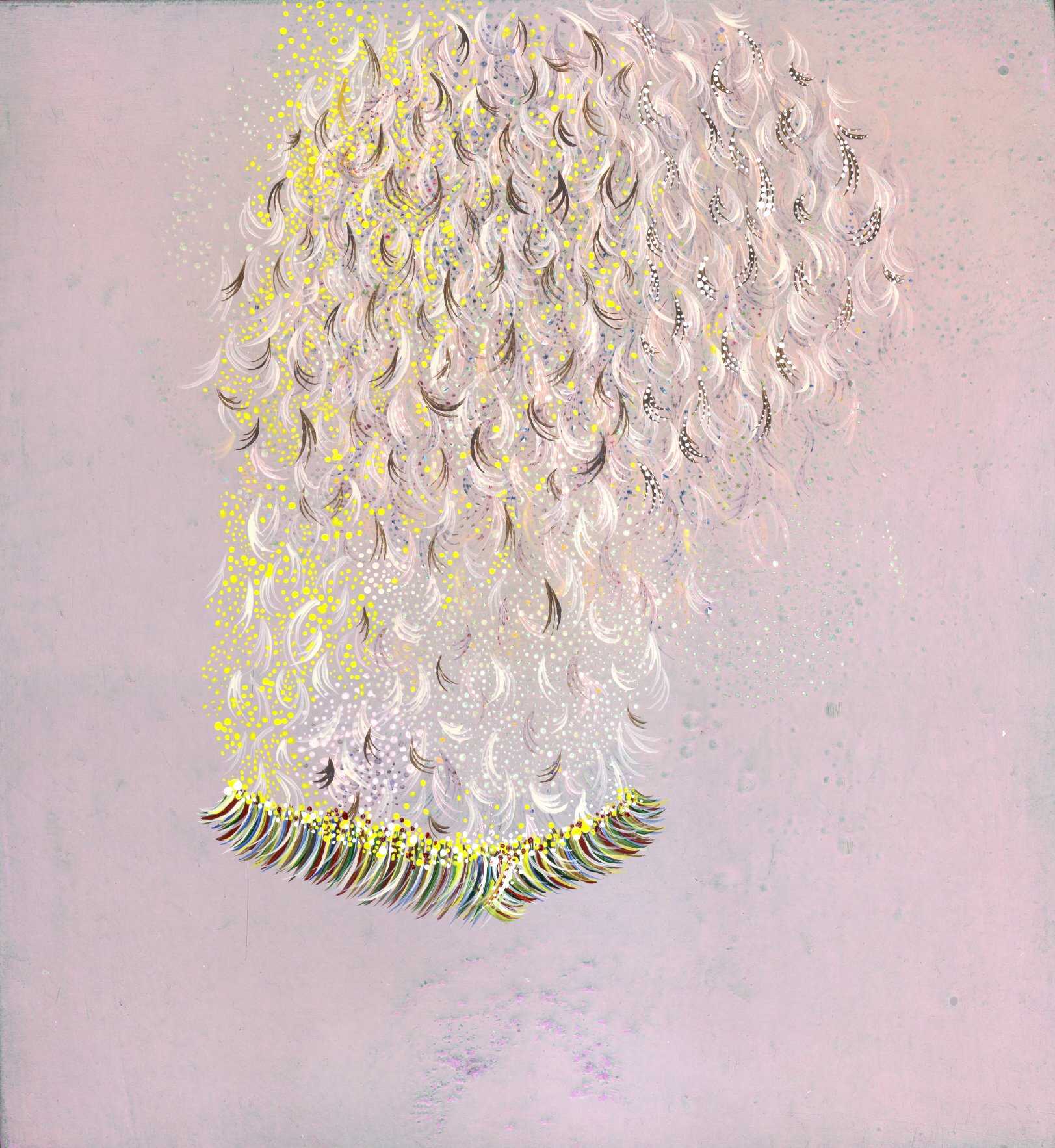

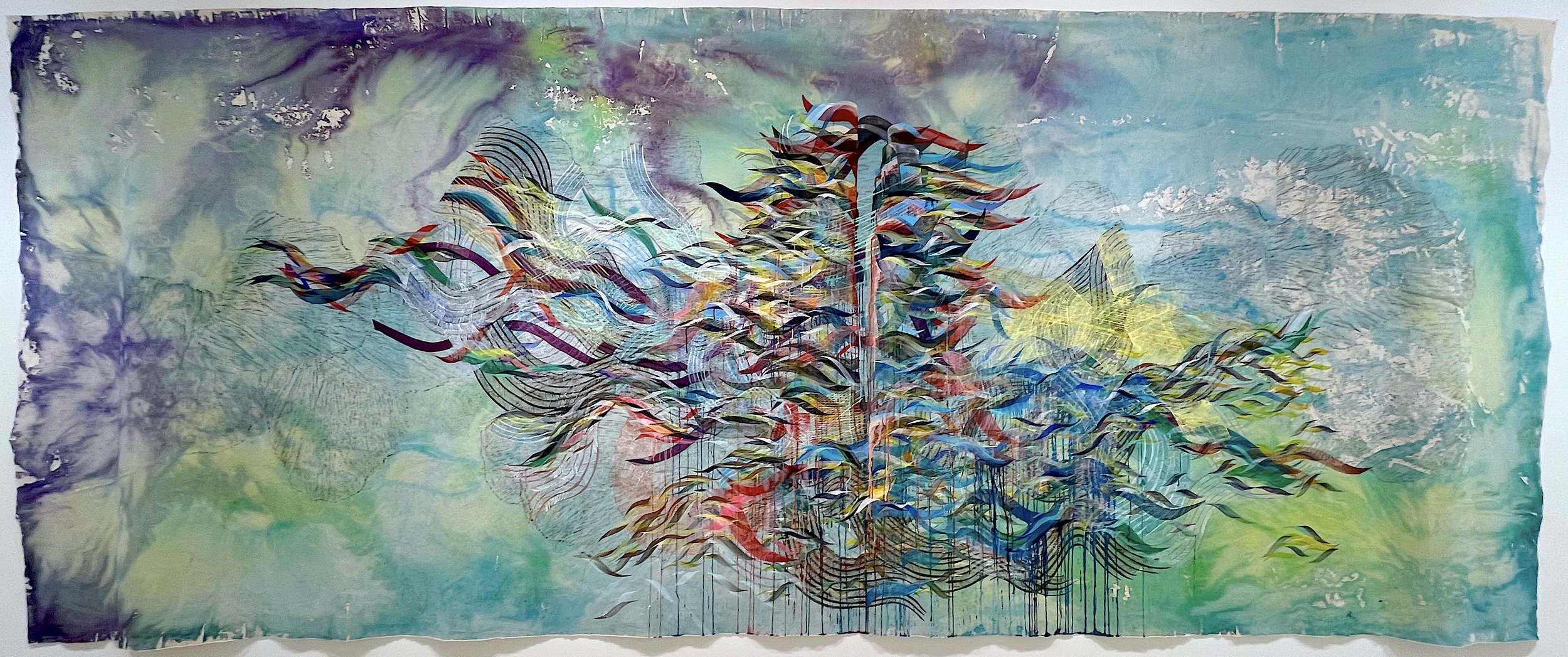

Alyse Rosner’s mural size paintings are a magnificent maelstrom of brushstrokes, drips, and vibrant color. In her current show at Rick Wester Fine Art, Rosner takes us on a journey that begins with harmonious surface gestures, growing increasingly chaotic as we move into the depths of the composition. Washes of saturated color surge across the unprimed canvas, cascading into the foreground in an effusion of polymer and pigment. Once we’ve crossed its threshold, the painting transports us into passages where we might not choose to enter. I found myself trapped in the lower left quadrant of Bracing Against the Wind, the show’s titular painting, an achromatic cul-de-sac that temporarily curbed any forward movement. But the discord is not without its merits; it is like the dissonance of Bach’s Cello Suites, encompassing the whole of human experience, from the euphoric to the claustrophobic and everything between. An 18-foot canvas is too large to depict a single subject or produce a solitary emotion; indeed, Rosner’s paintings are not about something, but are the thing itself. They are contained universes with their own language, logic, and weather systems, churning up responses that run the gamut of emotions. Her paintings are so broadly expressive that their interpretation will vary according to where one stands in relation to the canvas. By taking a few steps to the right, I was able to extricate myself from the fraught passage and return to the more palatable purples and blues in the foreground. Rosner begins each piece with graphite rubbings taken from her surroundings, including her wooden deck and a tree stump just outside her studio. Barely visible in the background, these references provide a measure of stability and ground us in the natural world. Her smaller canvases are more contained, an extension of our world and thus more easily digested. They are like microcosms from the larger cosmos, banished for their interest in pursuing beauty over chaos. In both her large- and medium-size paintings, Rosner commands her medium with the grace and humility required for working on a monumental scale, offering us a glimpse into her working process and emotional breadth.

MH: Your process starts with graphite rubbings from the deck outside your studio, or a cross-section of a tree trunk near your house. What was the inspiration behind that? Had you worked with rubbings prior to the large paintings?

AR: My mom is an artist, and when we were kids, she always gave us creative projects to do, including rubbings, so it wasn’t a foreign thing to me. Then in grad school I did some woodcut printing, but I realized that I loved making the block more than the print. In the early 2000s I started painting miniature woodblocks, 5 x 6 inches, with layers of acrylic on raw pine. That’s how the process evolved, and later I started thinking about how I could scale those up to make larger paintings. I thought maybe I’d work on a bigger piece of wood, but the logistics were overwhelming. Then I had the idea to make a rubbing of my deck, which has an exposed grain. There’s also a tree stump just outside my studio door, and it seemed like a natural thing to try. It was all an experiment, trying new ideas to shake things up, and I felt connected to it because it was all part of my surroundings.

MH: You mentioned that you move the raw canvas around a lot in the initial stages of the painting, literally dragging it outdoors to do the rubbings. You also hose it down, adding pigments to create large washes of color. Do I have that right? How would you describe the physicality of the process? It sounds both exhilarating and exhausting.

AR: That aspect is very physical, and I have to be geared up for that kind of physical activity. I’ll have a day that I do a lot of rubbings at once, which jumpstarts a body of work. It’s a very satisfying process – instant gratification – and can also be surprising, like when it materializes in a totally different way than I’d imagined. The large washes of color are with acrylic paint and water on the raw canvas. It starts out on the wall then goes to the ground, and as the paint dries it fades, so it goes through a few phases of adding more water and pigment. None of it is too mysterious, but it can be unpredictable.

MH: By the time you’ve finished the painting, the tree trunk rubbings are very faint, like ghosts of trees floating in the background. I read them as terre firma, a solid foundation for your energetic brushstrokes and complex compositions. How do you conceptualize the rubbings, and the fact that they all but disappear?

AR: They don’t always disappear. In the group of paintings in the current show, the rubbings are fainter, but other bodies of work have had much darker rubbings that assert themselves more strongly. The rubbings came out of the process of working on miniature paintings, where the incentive for the composition was the wood grain, a raw piece of pine. I used the grain as a way to orient a drawing, and my current rubbings serve the same purpose. By putting something down on the blank canvas, I have something to respond to that is personal and meaningful, so this has become an ingrained part of my process.

MH: It’s interesting how artists need to have something to get the ball rolling. Without some entry point on the paper or canvas, it can be hard to move into a new piece.

AR: Yes, you have to have some kind of strategy so you won’t be intimidated by the blank page. I had a visiting artist in grad school who suggested using the previous painting to start the next painting. I sometimes use previous paintings as a source for mark-making. I see it as a reference to propel the process forward.

MH: Do you have a conceptual basis for the rubbings? Like, are they the ground from which the composition is built, that sort of thing?

AR: They’re definitely the anchor. But when I’m painting, I don’t think about what it means or what it’s a picture of, I think more about how the marks relate to each other, and if they’re beginning to activate each other. When the marks finally activate, that’s when it becomes a painting. There’s content in the paintings that is not depicted by me, but is a preexisting content in the combination of the language and rubbings. It’s commenting on nature, life cycle, decomposition, growth, phenomena that we don’t understand, or that we try to understand. Lots of things can be projected onto them.

Bracing Against the Wind, 2022, graphite and acrylic on raw canvas, unstretched, 84 x 216 in.

MH: You went from painting miniature woodblocks to mural-size canvases, and it sounds like it took many years to realize. What process did you go through to scale up, and what were some of the issues that you came up against?

AR: Well, it’s been 23 years, so I guess I came up against a few things! When I was working on the miniature scale, my kids were babies, and it was as much as I could handle back then. Then there were the material challenges, learning the language and searching for my own voice, my own way of working. For some reason tiny and enormous have more in common than tiny and medium. Both the miniatures and the large canvases create a universe; they’re not a picture of something else, but they are the thing itself. The medium-size painting, 30 to 40 inches, often is a picture of the thing, and that’s the struggle for me. I prefer to make the thing rather than a picture of the thing. And the larger works are just a natural scale for me to work.

MH: You write that each painting is in response to the preceding painting, suggesting that your work engages in an ongoing conversation with itself. I’m intrigued by the idea of an artist’s materials embarking on their own journey, with the artist as their medium. Does this ring true for you? Namely, do you ever feel like the materials are in control, and you’re along for the ride?

AR: If you can get there, it’s a nice place to be! Once I get through the struggle of getting into the painting, I can get into a flow, and then it can feel like things are happening and I’m just participating.

MH: I’d imagine that working on such a large scale would amplify the feeling that you’re collaborating with the materials. Do you ever lose yourself in the process? Is there ever the sense of being overpowered by your own creation? Not in a Frankenstein kind of way, but with the feeling of not being equal to the task?

AR: Oh my god, of course! Definitely. Sometimes I think I’m kidding myself to think I can do this, and it can be overwhelming. Plus I often can’t see what I’m doing because I’m too close to it. It can take a few days to get into the process before I can be clear and have some perspective on what the painting is becoming. Things often happen out of sequence, or I make something that I don’t recognize, and it feels alarming, like I’ve totally lost my place and my practice. In those times, I work hard to let the painting exist as it is and see if over the course of a few weeks I can understand it. Basically, when I feel unsettled by the work, I feel like it’s going someplace that it hasn’t been before and that’s where growth happens, but it can be very uncomfortable.

Carrying Its Broken Shells, 2023, graphite and acrylic on raw canvas, unstretched, 84 x 216 in.

MH: Is there ever the feeling that you’re getting in the way of your materials?

AR: Sometimes I do, but I try to resist it. My work has a continuity, but there are also places where it moves in new directions. I hope that I let that happen.

MH: I’m interested in the idea that an artist can be a hindrance to the materials; that the materials want to express themselves through her, but she’s getting in the way. Artists do a lot of different things to get out of the way, like smoke weed or self-flagellate or whatever.

AR: I haven’t thought about that so I’m not sure how I get in the way or out of the way, either one. I have a routine, and habits can be good or restrictive.

MH: What brings it up for me is that you work on such a large scale, and I’m frankly in awe. There’s a lot of creative energy coming through you, as well as a lot of paint, and it would be easy for you to get in the way of the process, but you seem to handle it all with grace. Not to be a fawning fangirl, but it amazes me that your paintings hold together as these super-tight compositions. And they’re exquisitely beautiful!

AR: Thank you! Most of the time while the painting is developing, it looks terrible! Up until the last second it can be a mess. But when it looks the worst is the best for me, because when parts of it start to look good, I feel protective and try to save a section from being ruined. That’s when I get in the way – when I have a part that I’m protecting. You have to be willing to risk the good parts and trust that in the end, the risk is going to land you in a good place.

MH: You mentioned that as you’re working, you try to suspend judgment, and let the paint be as it is. Even if you don’t like how it’s going, the process may take you into new territory, rather than staying with the familiar. This takes a lot of trust, and I’m wondering where a mature artist is most apt to place her trust: in herself and her problem-solving capabilities, or in the medium to resolve itself? Is there a meaningful distinction to be made?

AR: I think you’re right. I think I put most faith in the process, and I suspend judgment as much as I can, because ultimately, I believe it’s going to resolve itself. I do have this ridiculous faith in moving forward in the painting, making intuitive decisions, and using the painting as a leverage for structuring decisions.

MH: When you have a deadline approaching, are you less apt to take chances and try new things?

AR: Hopefully things have progressed far enough so that by that time the deadline is getting close, I have a direction and it’s not as risky as when I’m deep in the middle of the process. For this show, I did work up to the very last second. But I work well under deadlines.

MH: I love the story of how Peggy Guggenheim commissioned Jackson Pollock to paint a large canvas for one of her dinner parties. The day before the event, he hadn’t even started it, but he painted the entire canvas late that night and delivered it the next day. I guess Pollock worked well under deadlines too! The story is probably apocryphal, but it speaks to the idea that the materials have their own agenda and impulse.

AR: Yes, you develop a familiarity and trust in the materials, as well as an intimate connection with your own process of working.

MH: You talk about the content of your work being autobiographical: they’re about who you are and what you’re going through, which is vulnerable for any artist. But you’ve experienced tragic personal loss with the death of your husband 11 years ago, and I’m curious how that showed up in your work? Were you able to process your grief in the studio?

AR: During the pandemic I felt a connection to this experience, as it was the tenth year since my husband passed away and it felt monumental to me. He was on morphine, which is color-coded for strength, and the color he was using happened to be phthalo green. After he passed away, that color really resonated for me. Prior to that my work was monochromatic, so when I started to incorporate this garish color into my work, it called for more color in response. The colors became vivid and synthetic, which was a big shift for me. It felt like a silent memorial, but people didn’t know that because I didn’t feel comfortable sharing it for a long time. Then during the pandemic there was such a collective sense of grief, and so many people had lost loved ones that I felt comfortable talking about it. Eventually that aspect of my work entered into my artist statement, and into my discussion of the work more publicly.

MH: There’s been so much grief and loss due to the pandemic, war, and climate change, and artists have found ways to express it through their respective mediums. The result is a lot of emotional art being shown right now! Have you noticed that? It seems that there’s an abundance of art in the galleries that’s super vulnerable, as if a huge, collective wound has been ripped open.

AR: When something difficult is happening to you, there’s the feeling that you’re in it alone, but now there’s this collective feeling of grief and people are living parallel lives. I think artists are more inclined to share those emotional upheavals, and they express it in different ways. I haven’t always felt comfortable sharing openly, but maybe I’m more comfortable now because these things are amplified due to the pandemic.

MH: I’ve noticed that the work in galleries has become more vulnerable and intimate in scale. I’m thinking of the recent shows of Carol Saft and Jackie Shatz, very small paintings and sculptures that carry a lot of emotion. I wonder if the collective wound is calling for more intimate works.

AR: I know both of their works. It’s terrible that the collective wound exists, but I think it’s good that people are willing to share it more openly.

MH: Is your work emotional? Behind the beautiful, organic patterns on the surface of the canvas, I see passages that look like they’re composed in a minor key. Are you orchestrating an emotional response?

AR: My process is really a call and response, an intuitive process that’s probably more formal than it is emotional. but it’s also conceivable that the emotional content is in the back of my mind when I’m making decisions. I don’t know if I can separate that.

MH: That’s fair. In your painting Bracing Against the Wind, the far left the section seemed dark and brooding, a singular passage in your larger body of work. Was I reading into it, or did you paint it that way?

AR: It’s open to interpretation. I don’t usually use such dark colors, but I was indirectly involved with the forest fires on the West Coast because my siblings live there. I was experimenting with the smoky sensation in some earlier paintings, so I was trying to bring a darker palette into the painting by having black and umber around the edges, and that’s how it evolved.

MH: What’s the best part about being an artist?

AR: I can’t conceive of doing anything else, so I feel lucky that I’m able to do it. To be in the studio and make the paintings and be able to share them is a luxury, so I also feel fortunate in that regard.

MH: What is your predominant drive in making art?

There’s something hardwired about the need to make something. I can’t not do it! I can take a break maybe, but I’ve always had the physical need to create something. One thing that I learned during the pandemic is that art matters and making something physical is important. It’s very meaningful to be a part of that.

Bracing Against the Wind runs through April 15th at RWFA.

www.alyserosner.com

IMAGE LIST

1. Zephyr, 2023, acrylic and graphite on raw canvas, 60 x 54 in.

2. Oracle, 2022, acrylic and graphite on raw canvas, 46 x 36 in.

3. Flight Burdock, 2022, acrylic and graphite on raw canvas, 33 x 30 in.

4. Bracing Against the Wind, current installation at RWFA, NY, NY

5. Rosner II, 2008, acrylic and graphite on yupo paper, 22 x 20 in.

6. With Wood Grain, 2008, acrylic and graphite on yupo paper, 22 x 20 in.

7. With Wood Grain XL, 2008, acrylic and graphite on yupo paper, 22 x 20 in.

8. Untitled, 2009, acrylic and graphite on yupo paper, 60 x 55 in.

9. Moment (Flutter IV), 2006, acrylic on raw pine, 6 x 5 in.

10. Moment (Lashes II), 2006, acrylic on raw pine, 6 x 5 in.

11. Moment (Lashes III), 2006, acrylic on raw pine, 6 x 5 in.

12. Moment (Rickrack V), 2006, acrylic on raw pine, 6 x 5 in.

13. Moment (Unnamed II), 2006, acrylic on raw pine, 6 x 5 in.

14. Moment (Unnamed III), 2006, acrylic on raw pine, 6 x 5 in.

15. In the studio.

16. Graphite rubbings in the studio.

17. Transporting canvas for graphite rubbings.

18. Rubbings in process.

19. The artist in her studio.