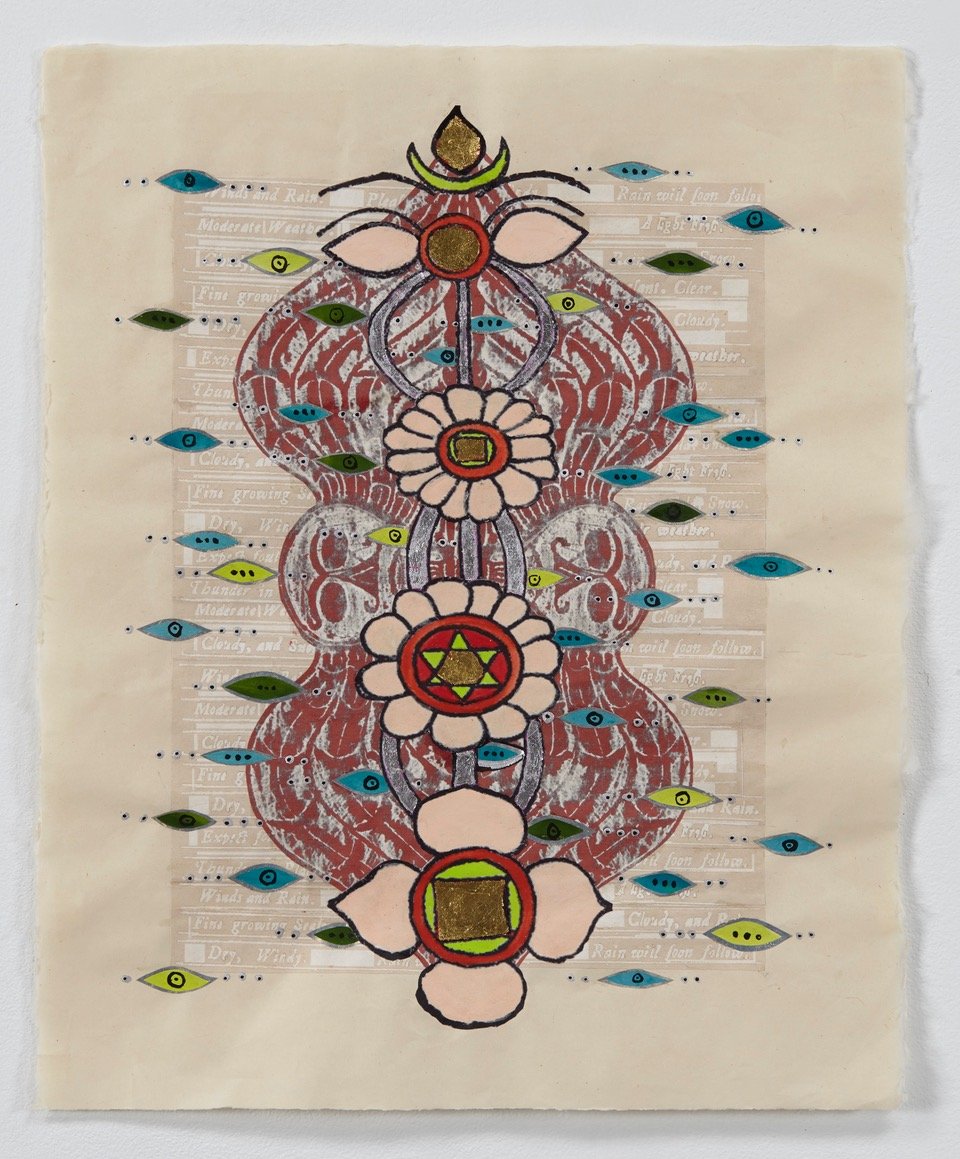

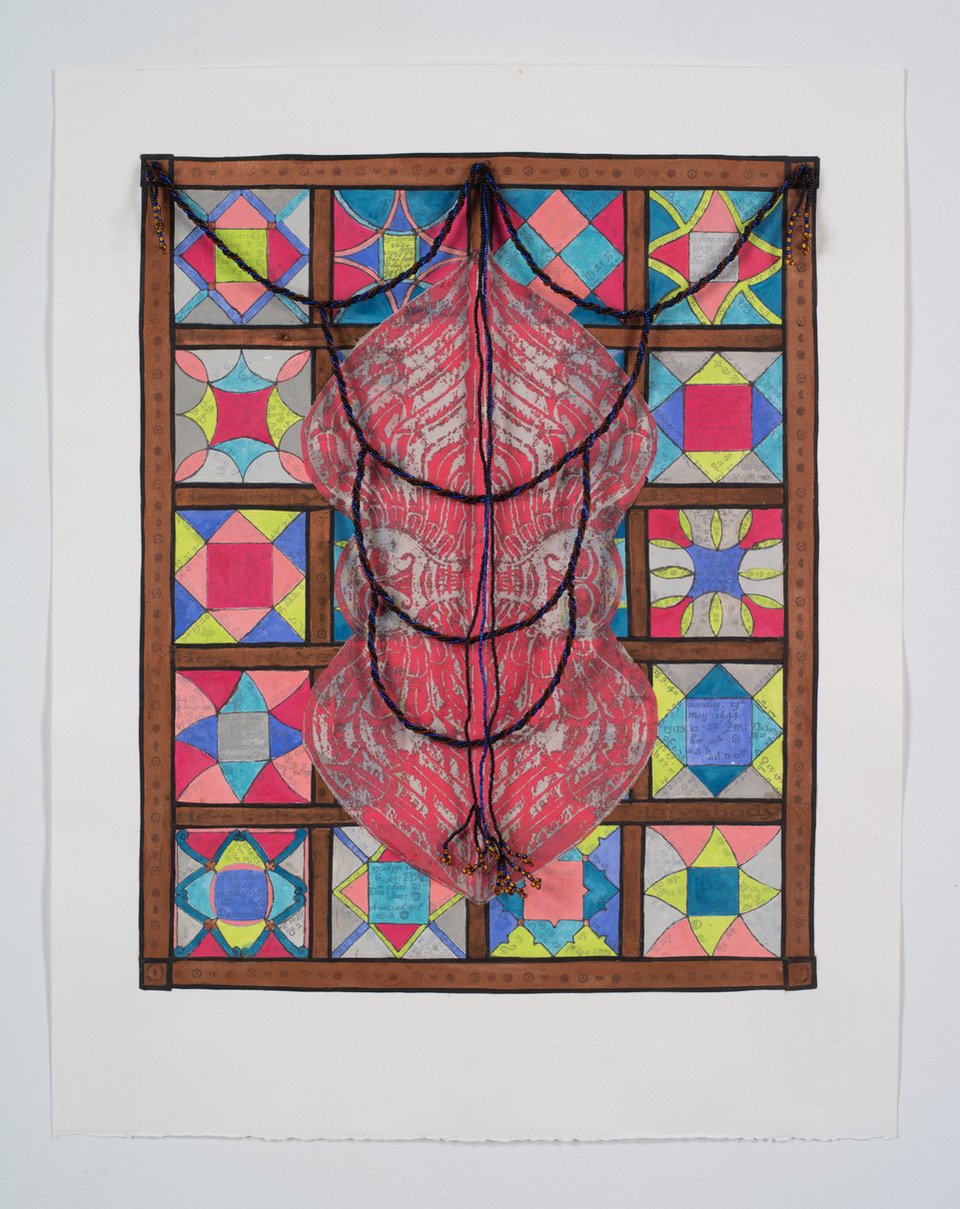

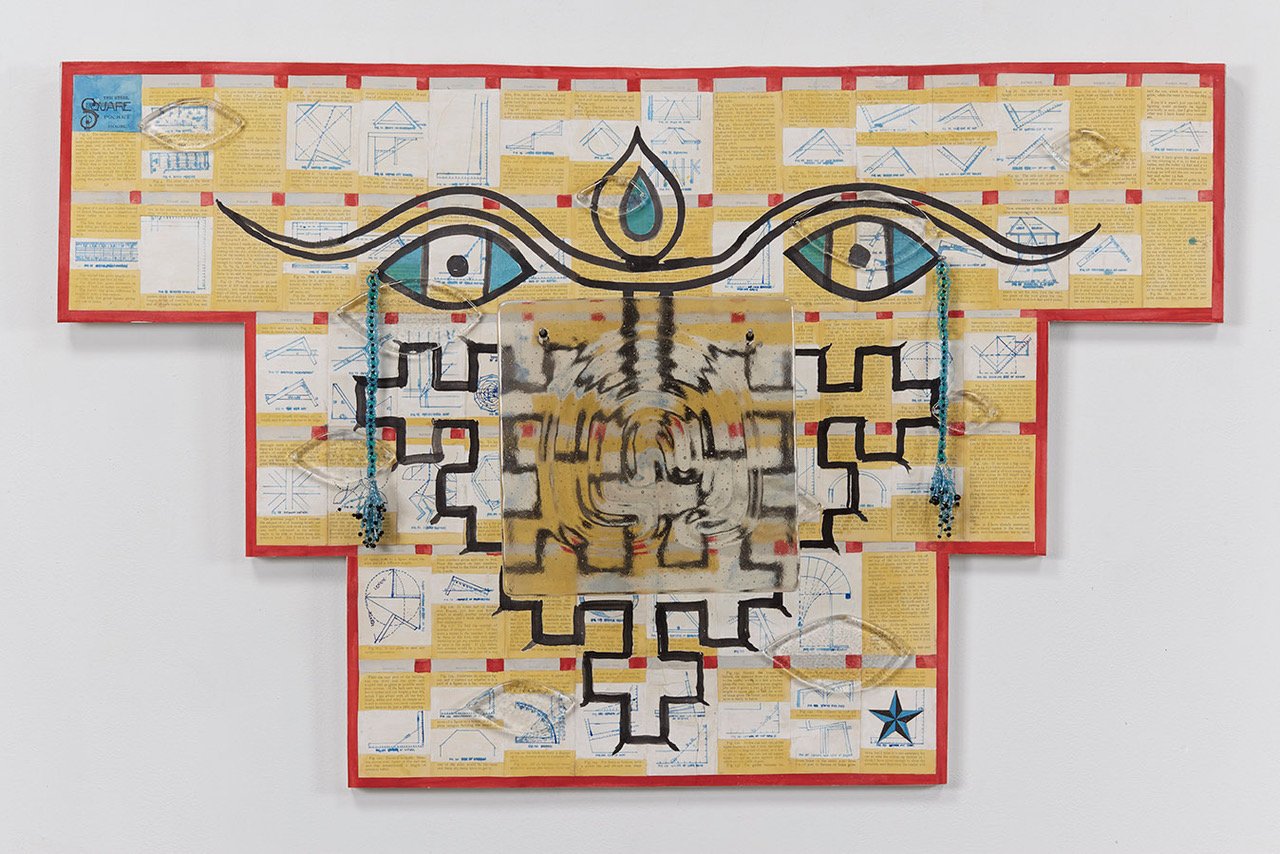

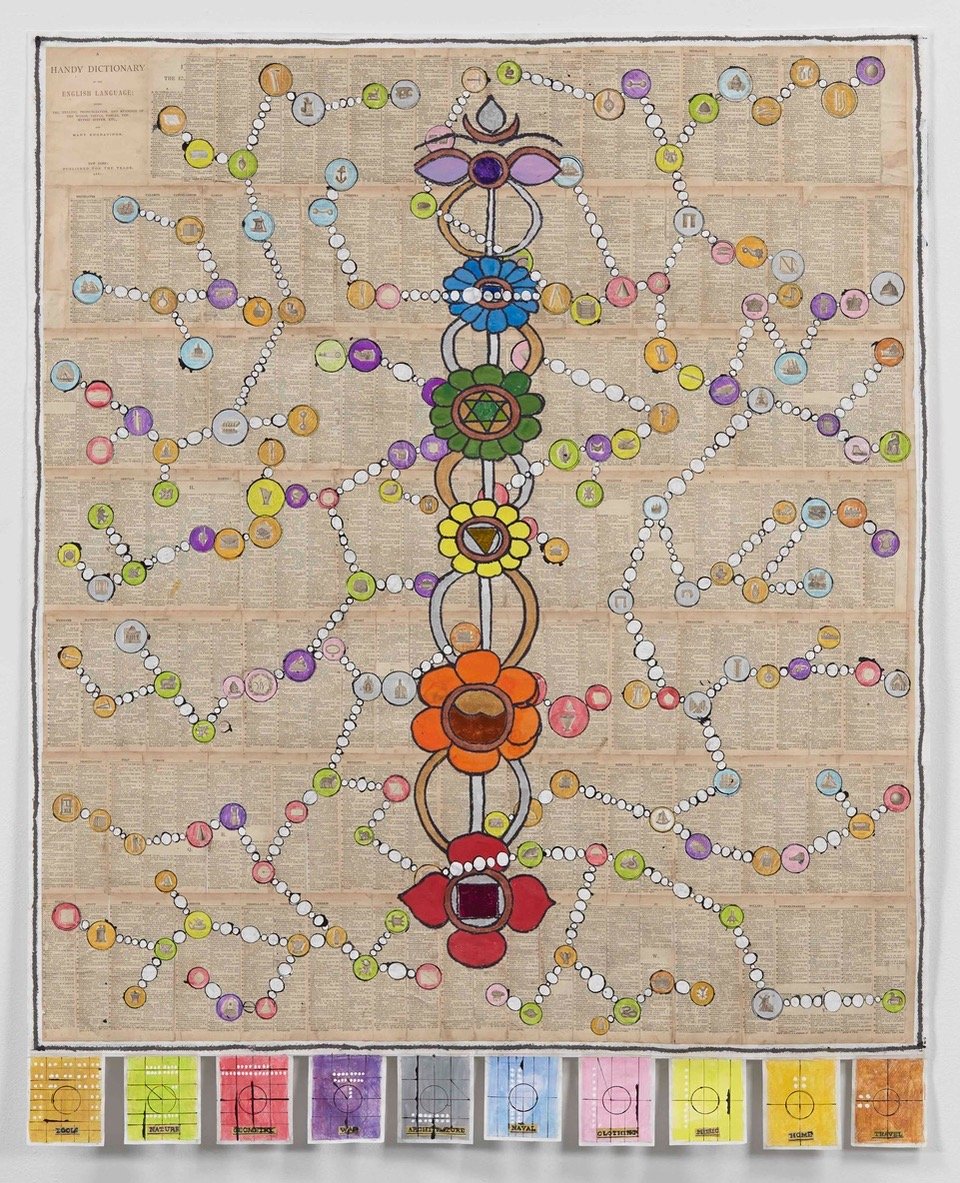

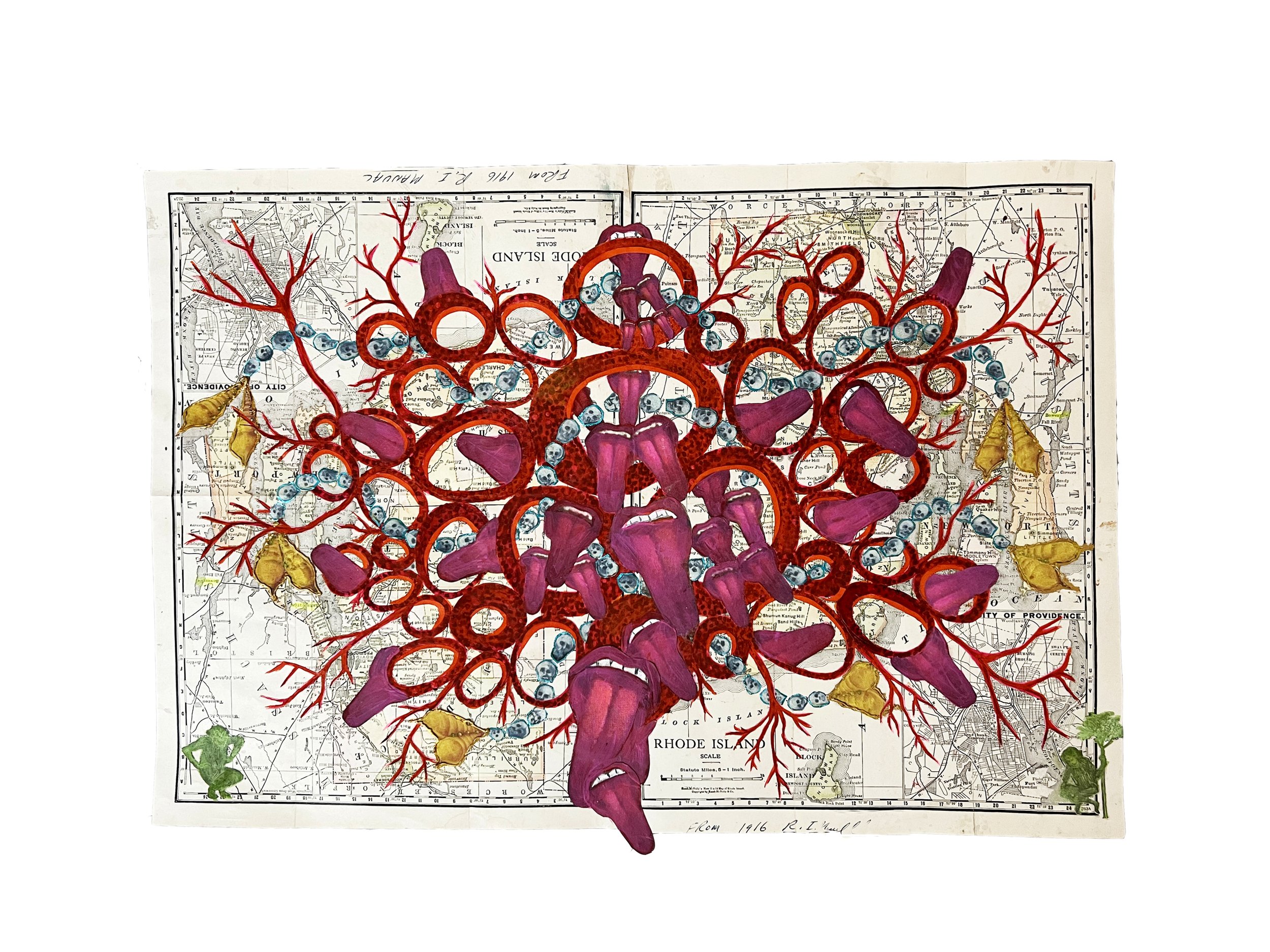

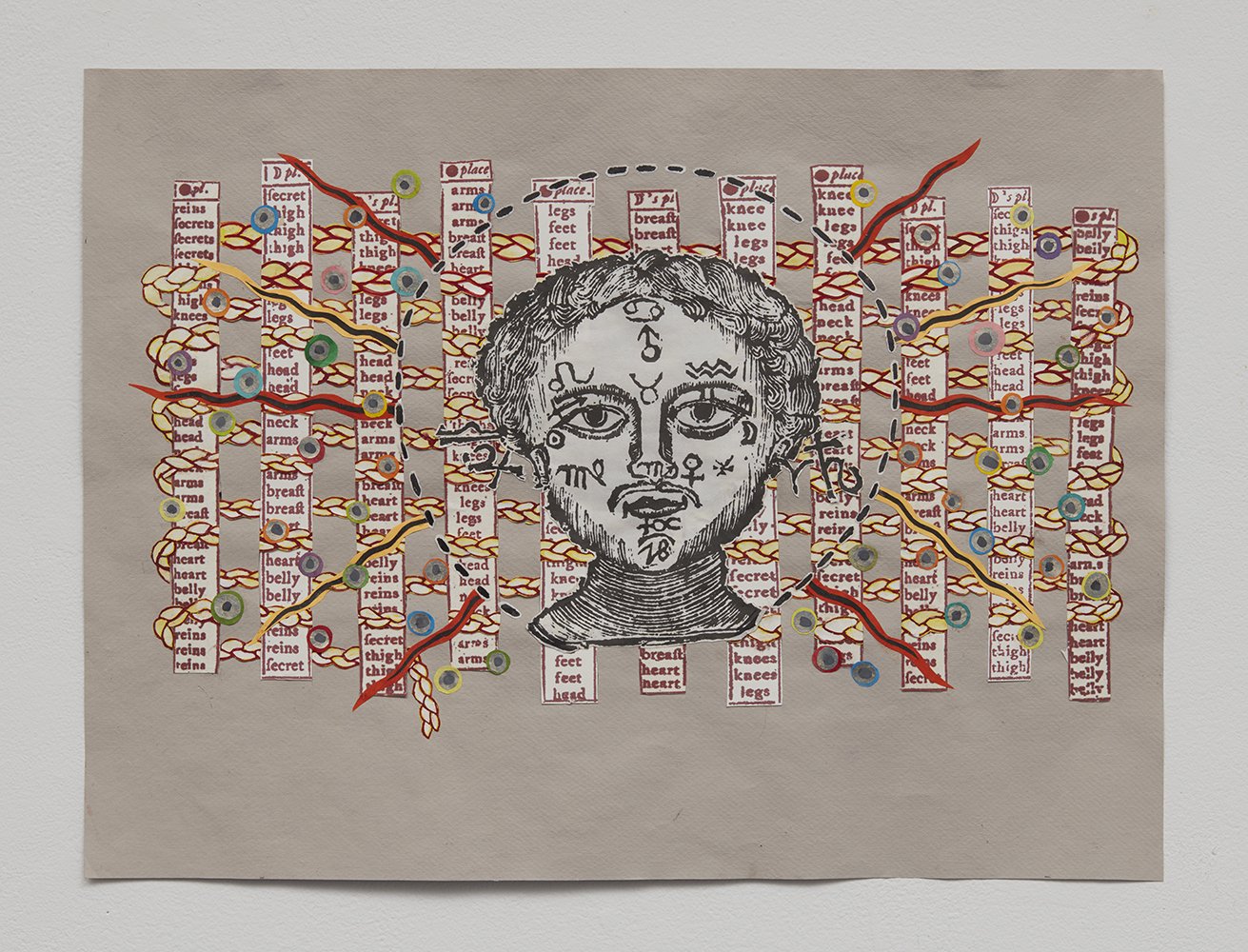

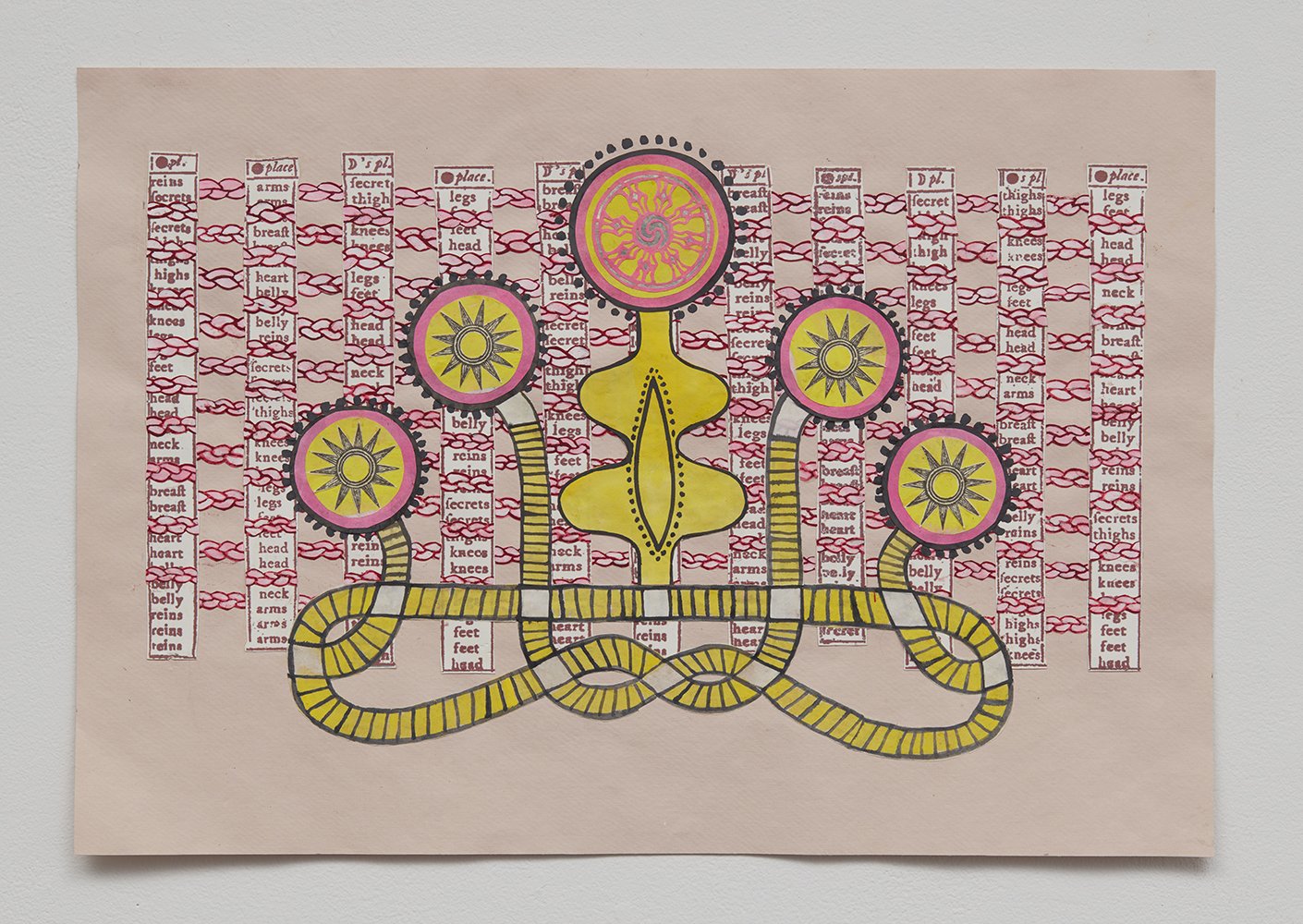

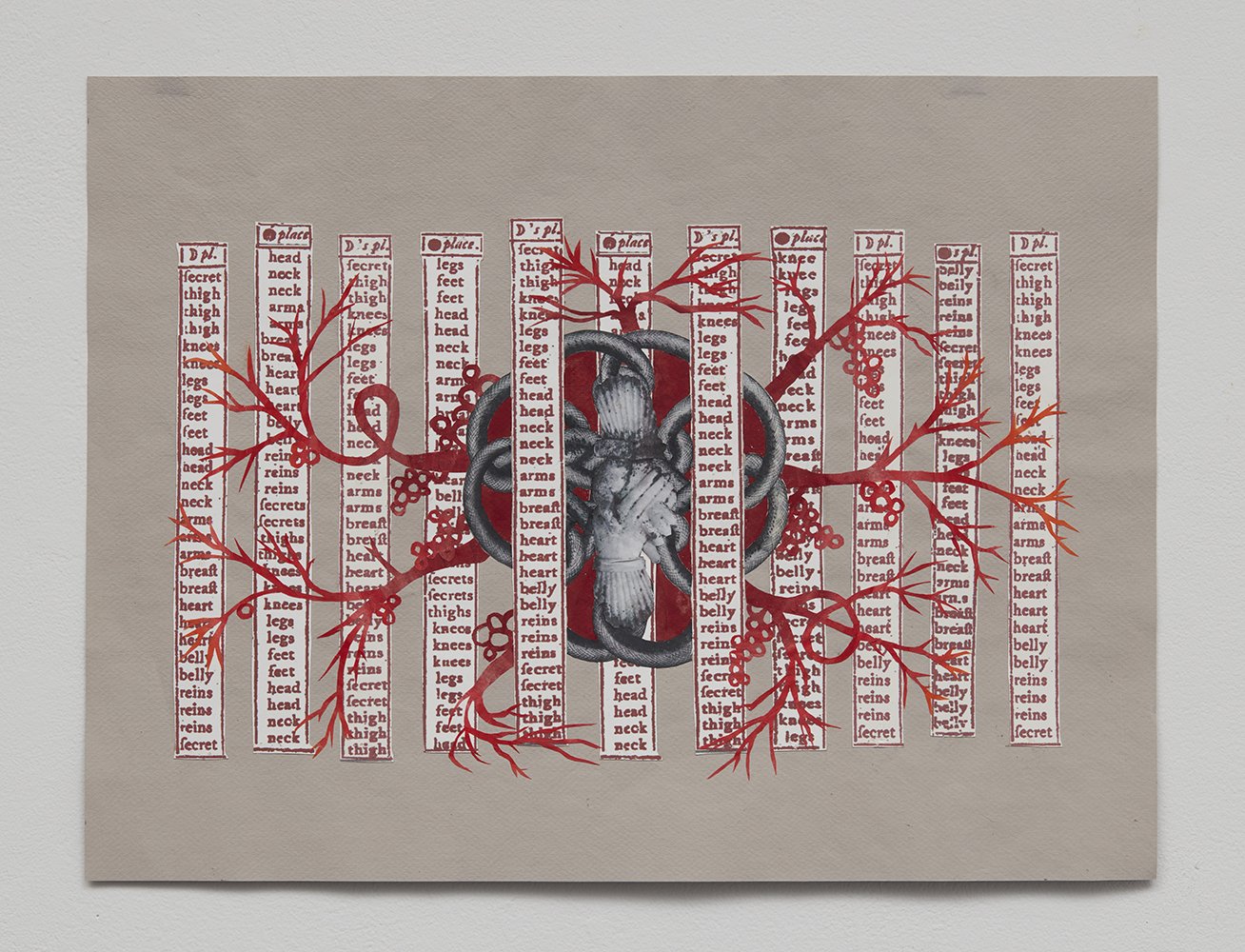

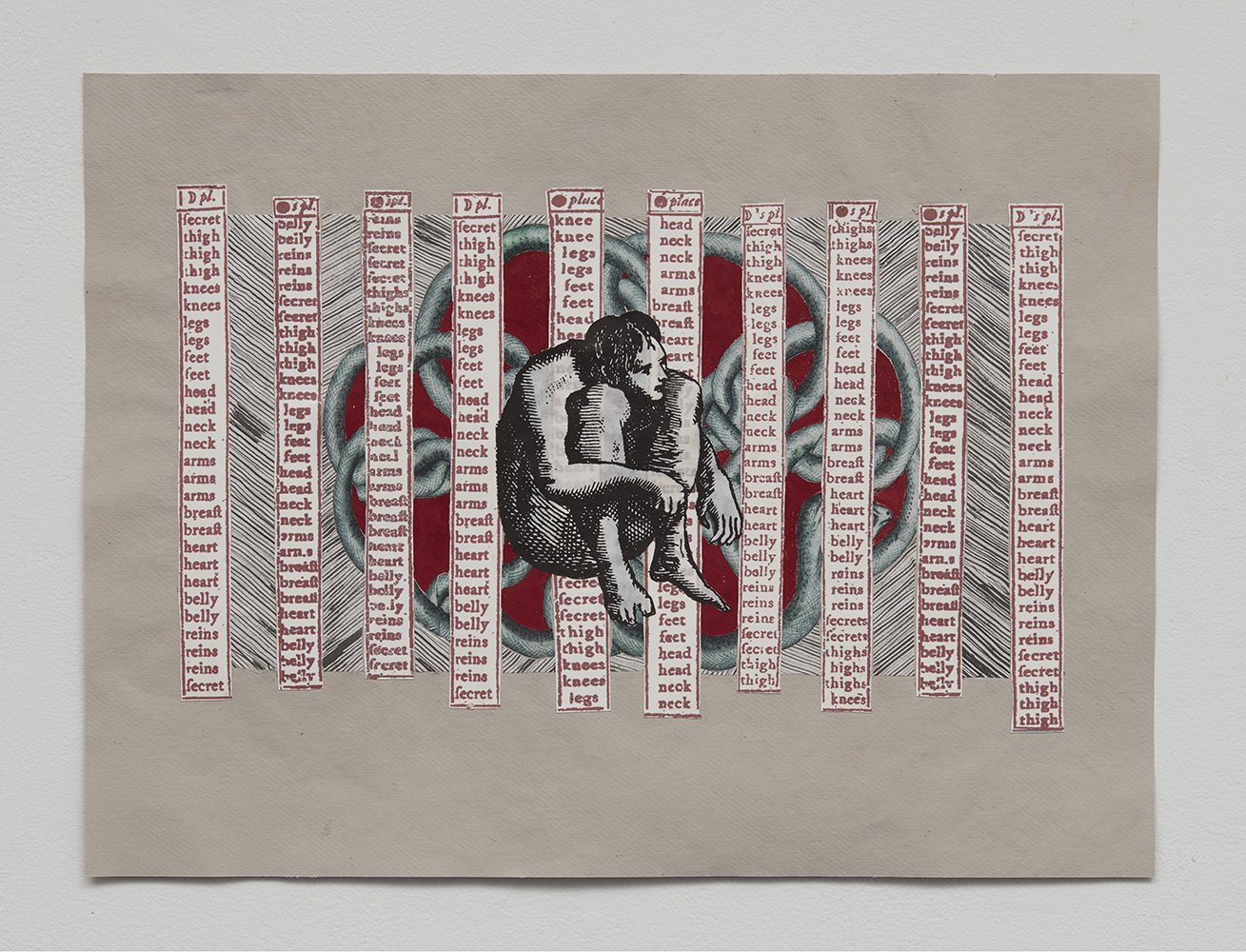

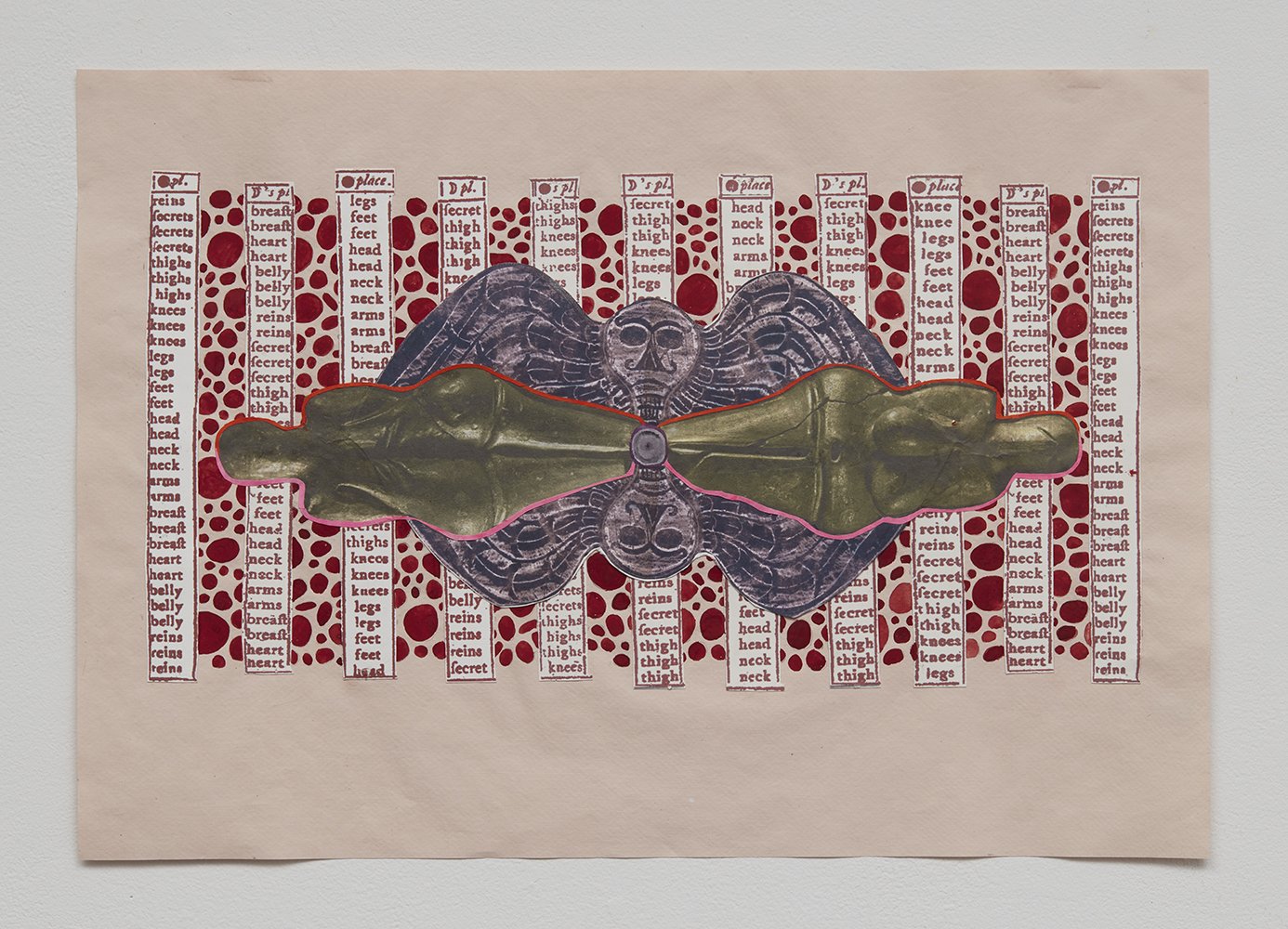

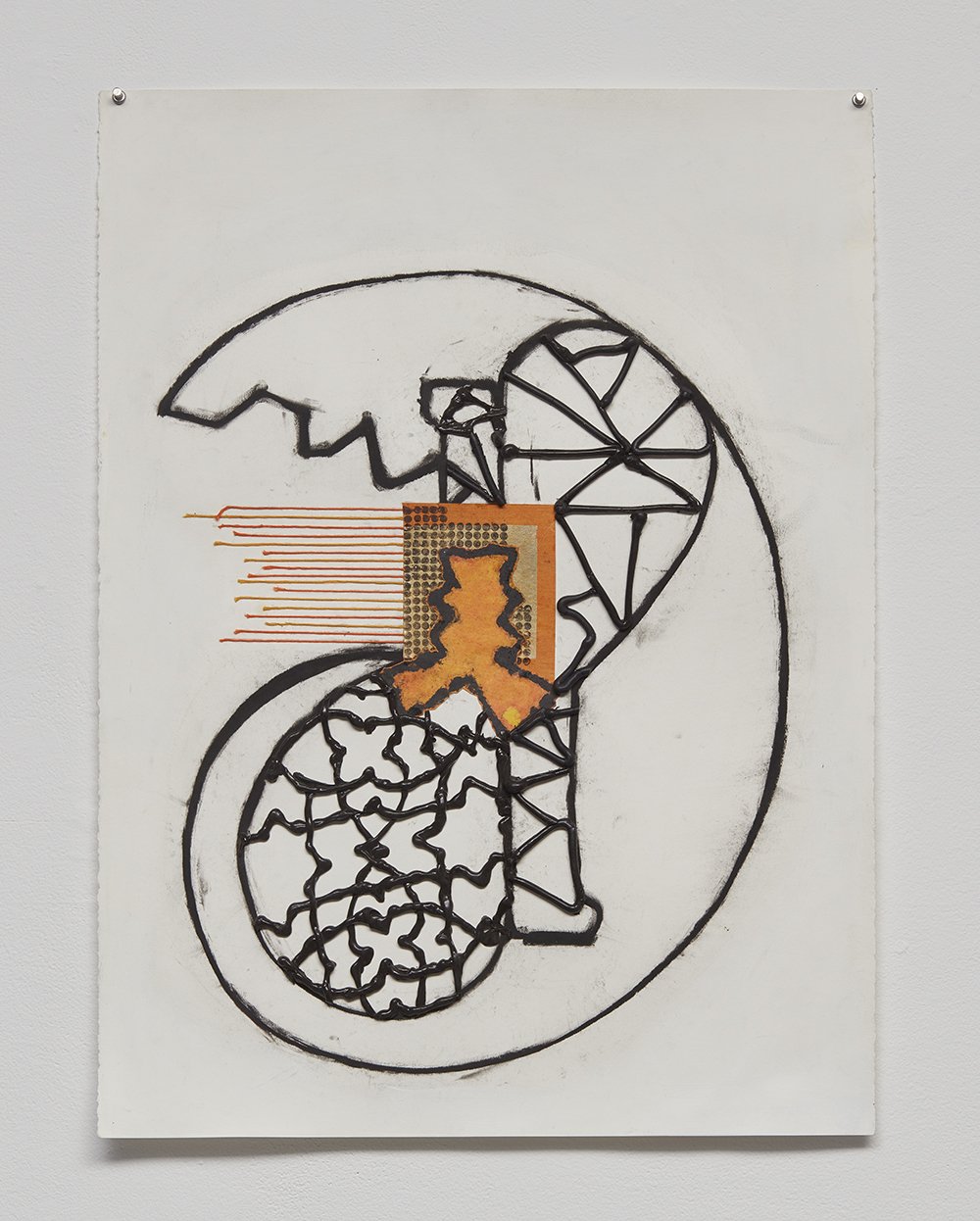

Nancy Bowen’s current show at SUNY Westchester Community College, Sometimes A Body Is Not Just a Body, features sculptures and drawings from 1992-2022. Her work considers the female body from the female perspective, rather than the focus of the male gaze. Since the 1970s, feminist artists have been challenging the traditional depiction of women in art and culture. As a young artist at the time, Bowen asked what it felt like to be inside that body, and her work became an interior exploration of the female form. She excavates the myriad networks of the body, including the digestive, reproductive, and chakra systems, probing the hidden structures of the female anatomy and bringing them into the light. Liberated from the oppressive male gaze, Bowen reveals the essence of femininity with all its shadows and complexities, a freedom granted to women artists beginning with her generation. In 2000 she traveled to India, where she was inspired by the Hindu representation of the chakras, the energy centers that correspond to the functions of the body. In her works on paper, Bowen integrates Eastern symbology with Western feminism to create a powerful expression of the divine feminine. Some of the drawings contain categorized lists of body parts (feet, breasts, thighs), which suggest that indeed, sometimes a body is not just a body, but an inventory of organs and orifices. For over half a century, women artists have been free to express radical images of themselves without the fear of censorship or retribution. If the progress of a civilization can be measured by the way in which the female body is portrayed in its art, Bowen’s work has been an essential contribution to our evolution and enlightenment.

MH: Your current show, Sometimes a Body Is Not Just a Body, features selected works from 1992 to the present. I’m sure you have mountains of work from such a long stretch of time, so how did you select pieces for this show? What were you thinking about as you put the show together?

NB: I worked with Joe Morris, the gallery director of the Westchester Community College Art Gallery, and we chose works that had an interesting dialogue between materials and content. We were also looking for pieces that would have a dialogue with each other and that showed a through line from my old work to the present.

MH: In the late 70s you were making figurative sculptures, and your work was about the female body from the female perspective. Then you started fragmenting the female body and expressing what it felt like to be inside that body. Would you talk about your thinking and process around that, and where it led you?

NB: As a young artist I was asking the questions that a lot of women artists were asking at the time, like what would a female body made by a female artist look like? This was coming from John Berger’s “Ways of Seeing” and thinking about how the male gaze had determined the way women were portrayed throughout art history. The feminist art world had started to change, and artists were looking at images of women through the ways they were constructed in the media – artists like Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, and Laurie Simmons. Then there were the constructivist feminists who were applauding this work, saying that it was impossible to make an image of a woman that wasn’t seen through the male gaze. So that shut down artists like me who were still portraying women. It was almost as if there was a fatwa against women making images of women! But my response then and now is that if we don’t make images of ourselves, then we’re erasing ourselves from history, or we’re letting others dictate how we’re being shown.

MH: When did you begin to express how it felt to be inside the female body, and how did the idea come to you?

NB: In 1989 I lived in Rome for a year, and while I was there, I got to see La Specola in Florence, a collection of anatomical wax models from the eighteenth century that were a collaboration between artists and scientists. They were these incredible, full-scale images of women made from plaster and wax, with long hair and pearls, and their intestines were beautifully splayed out on top of them. It intrigued me and was the inspiration behind making the inside of the female body visible and beautiful.

MH: The 70s and 80s were a complicated era for young women. On one hand we were enjoined to buck the system and become hairy-legged feminists, and on the other we had the anemic supermodels who made us feel overweight and undesirable. Did you struggle with this? How did this tension show up in your portrayal of the female body?

NB: Yes, well I never considered being a supermodel! I was more concerned with practical things, like carrying a 100-pound bag of plaster on my shoulder or picking up a piece of bronze. Art school was still macho in the 70s; when I was in undergrad, I didn’t have any women teachers at all. But at the Art Institute of Chicago, they had an incredible visiting artist program, and all these early feminist artists were coming through as visitors: Marsha Tucker, Miriam Shapiro, Louise Bourgeois, Elizabeth Murray, and my teacher Ree Morton, who was a huge influence.

MH: It doesn’t sound like you struggled with body image, so perhaps there wasn’t much tension around that in your work.

NB: Yeah, I never wanted to be Farrah Fawcett. I was never a thin person, and it wasn’t something I thought about that much. I guess I’m lucky in that respect. I was looking more at the gestures of the figure than what the body looked like.

MH: As a long-term art educator, do you see female art students expressing feminism as insistently today as they did back when you were a student? Are they more apt to take their rights and equality for granted?

NB: I’ve seen reactions to feminism change a lot in the 30 years that I’ve been teaching. When I was coming up, women were clear about wanting to be feminists and demanding our rights, demanding female teachers and things like that. Now students take it for granted because they’ve grown up with parents who raised them as feminists. The big difference I see now is that young men are way more feminist than they were when I was in school. So the change that’s most obvious is the way parents have raised their sons to see women as their equals, and not to expect them to cook dinner. And now with all the incursions on reproductive rights, I hear young women talking about it and becoming aware that our rights are not something to be taken for granted. At Purchase College where I teach, we’re a super trans-friendly school, so that conversation is very up front in students’ artwork.

MH: When and why did you become interested in Hindu and Buddhist art? What about the imagery speaks to you?

NB: When I was making figurative sculpture, I was looking at examples from around the world, trying to find historical models of how I might think about making figures. I found that in a lot of cultures, the men are huge, and the women standing next to them are little. But in Indian culture, the women and men are the same size. The goddesses and gods were sexualized in a way that Western sculpture is not, and the women were enjoying themselves as much as the men. So I started going to India, where I was introduced to tantric painting. I saw Ajit Mookerjee’s amazing collection of scroll drawings of the chakra systems in bodies, and I started researching this tradition of depicting the chakras. I discovered that they existed primarily as paintings, but not as sculptures.

MH: As an aside, do you think in those cultures where the divine feminine was predominant there were any feminists? I somehow can’t feature Shakti and Shekinah burning their bras or participating in a Million Goddess March. When a woman is fully empowered, is there the need to defend herself?

NB: Yes, because even when a woman is fully empowered, we still live in the world that we live in. Ron DeSantis and all these politicians are trying to take away every right that we have. So unfortunately, yes. And in Indian culture, they’re really in need of feminism. In the rural areas, there’s still the tradition called sati that says when the husband dies, the family is allowed to burn the wife if she’d be a financial burden on the family. This practice has been banned legally, but it still goes on.

MH: This segues into a question that I think about often: are you a feminist for yourself, or for other women?

NB: For everyone!

MH: The reason I ask is that there are women who have never felt oppressed or discriminated against for being a woman. Her feminism isn’t so much for herself, but for the young women who no longer have the legal right to decide for themselves when to have a child. And she’s a feminist for trans-women, who feel unsafe in their chosen identities. I’m curious if you’ve ever experienced sexist discrimination in your own life?

NB: Yes, I have. At my job at Purchase, there was a time when the women on our faculty had salaries that were way less than the men of the same rank. I also experienced sexism at my previous job at Columbia. I grew up with a sexist dad; I grew up under the patriarchy. We live in a very sexist society, where men make laws about reproductive rights, and I worry about the future of young women.

MH: After spending some time with your work, I see two dominant threads: a visceral exploration of the feminine, and your intrigue with Eastern mystical traditions. They complement each other well, and it’s almost inevitable that you became interested in the chakras. Would you talk about your depiction of the chakra system?

NB: In 1989 I was living in Rome, and I made an edition of hand-held chakras that were cast in glass. Then I started making drawings of the chakras, some of which were literal depictions. Each chakra has its traditional way of being depicted; there are images, sounds, numbers, colors, even animals related to each chakra. It feeds into something else that I’m interested in, which is making work in which information systems collide.

MH: The content of an artist’s work is often something that creates conflict within her psyche. For me it’s religion, for you maybe it’s the female body vis-à-vis the male gaze, but it’s a complex that provokes and jabs at you until you make peace with it. Do you ever feel that you’re in the process of resolving some internal conflict through your creative process?

NB: No. I wrestle a little with spirituality, how I experience and express it. But no, I don’t feel conflicted.

MH: You seem like a singularly unoppressed woman!

NB: Haha! I’ve had a lot of therapy.

MH: Is there something that keeps pulling you back into the studio, as if you’re sorting it out through your creative process?

NB: No, I don’t have that. I get a material bug. I find a new material and I have to figure out what I can do with it. I have a restless mind, and need new challenges, like learning a new skill that I can bring into my work.

MH: Does this desire to try out new materials show up as a tension?

NB: Yes, that’s where the tension is for me. What happens when I put this next to this? Is that going to work or not work? What material works best for this piece?

MH: As a multidisciplinary artist, do you see your expression of the female body being as much about the materials as it is the content?

NB: I would say yes to both materials and content because our experience in our body changes all the time. When I started out, I was in a young body, and now I’m in an aging body, and the experience feels very different. In terms of materials, I oftentimes embed content into the material, or the way I combine materials makes a kind of content. And that’s always changing too, because in the sculpture world they’re always inventing new materials. Working in ceramics, there’s a lot I continue to discover about the materials.

MH: I saw your installation Spectral Evidence in Provincetown in 2021, and it’s in your current show as well. There is surely no episode in the history of our country that was darker for women than the Salem witch trials, which are the inspiration behind the work. Can you say a few words about this piece?

NB: I have an ancestor, Samuel Sewall, who presided over the Salem witch trials. I went to Salem about 5 years ago, and found a book about him, “"Judge Sewall's Apology: The Salem Witch Trials and the Forming of an American Conscience”, which tells how he recanted, repented, and spent the rest of his life atoning for the killings. So in my installation I’m stepping in for my ancestor, making him experience his guilt and face off the graves of the people he murdered. It was a way to make symbolic amends for the wrongs of the past. I was making this during the Trump presidency, so there were parallels to the current political situation: fake news, corruption, greed. The whole thing was a spectacle, like lynching would later be.

MH: In reference to the title of your show, I have to ask: When is a body not just a body?

NB: A body isn’t always represented as a picture or a sculpture. In the some of the drawings in the show, I depict the body as a list of body parts.

MH: What’s the best part about being an artist?

NB: I get to do what I want! I get so much pleasure out of working with materials and creating visual images, and it makes me happy when people see my work get pleasure out of it.