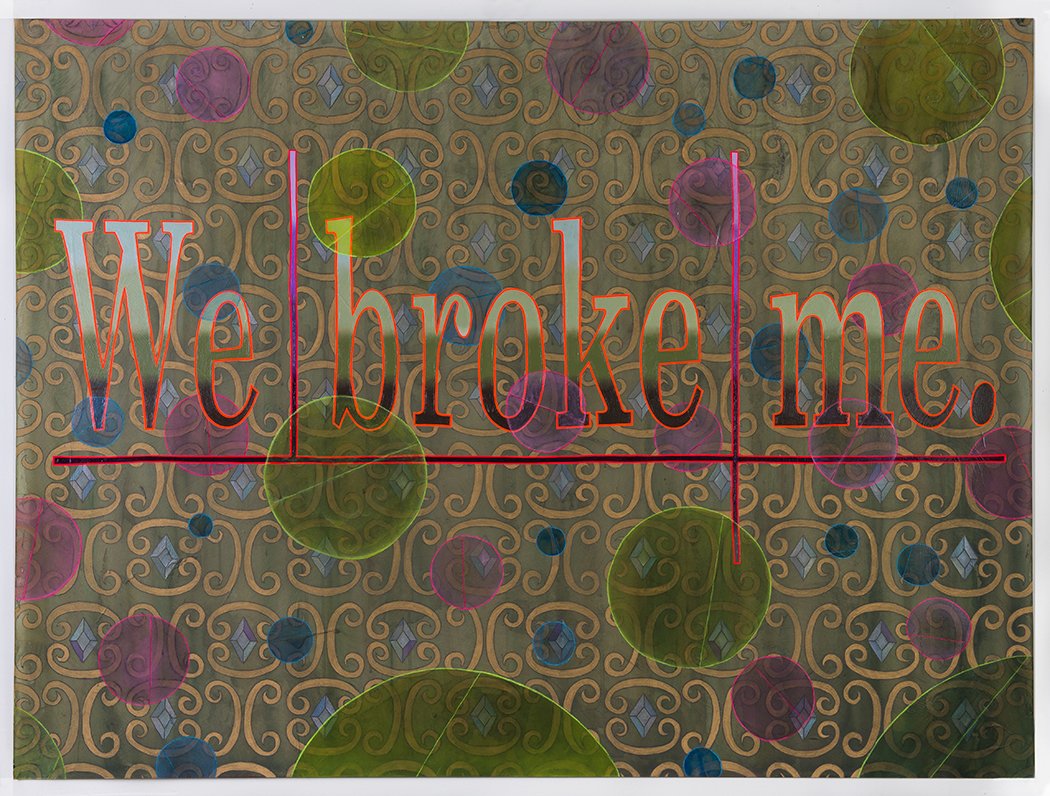

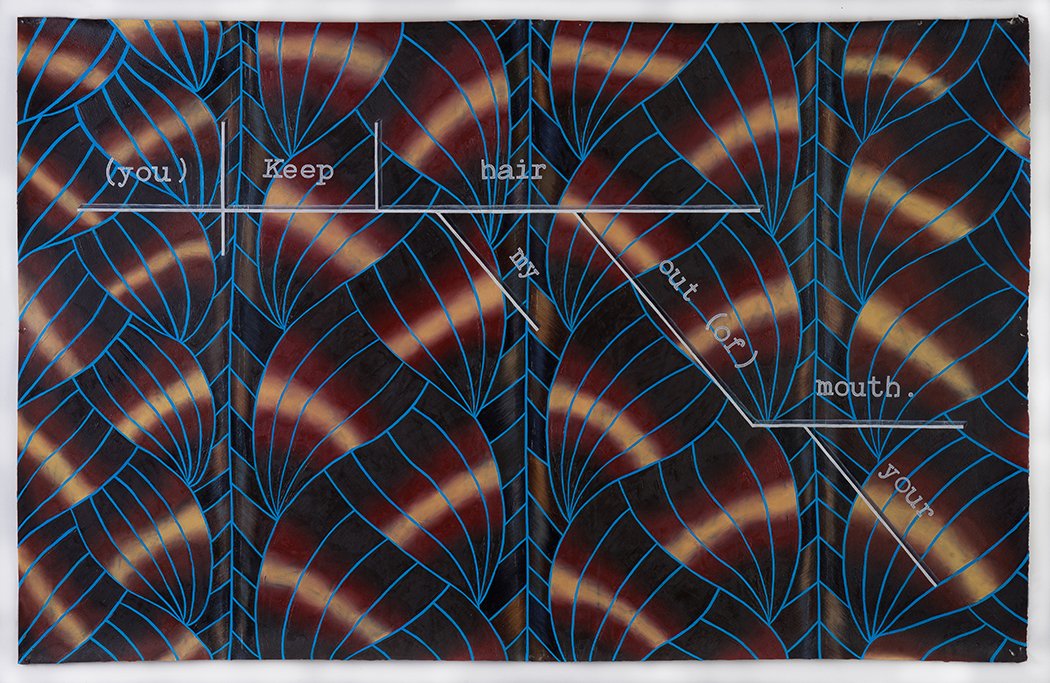

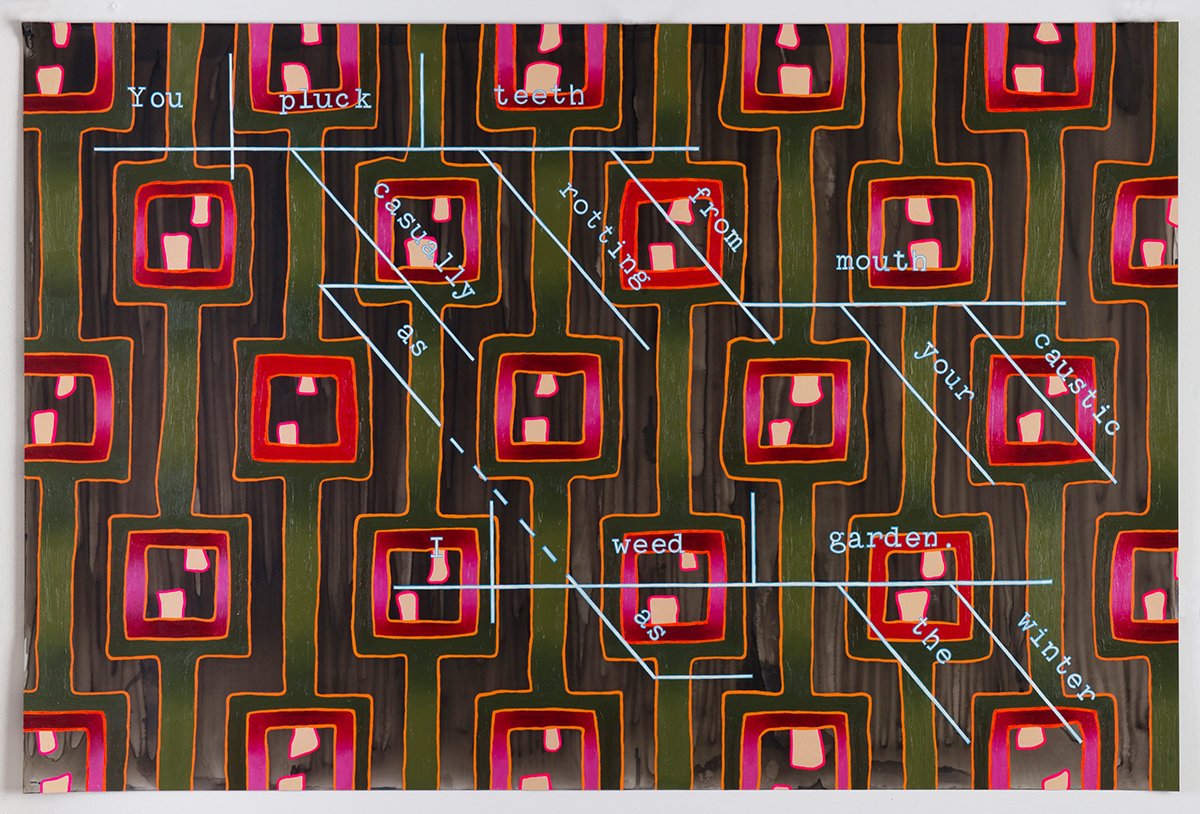

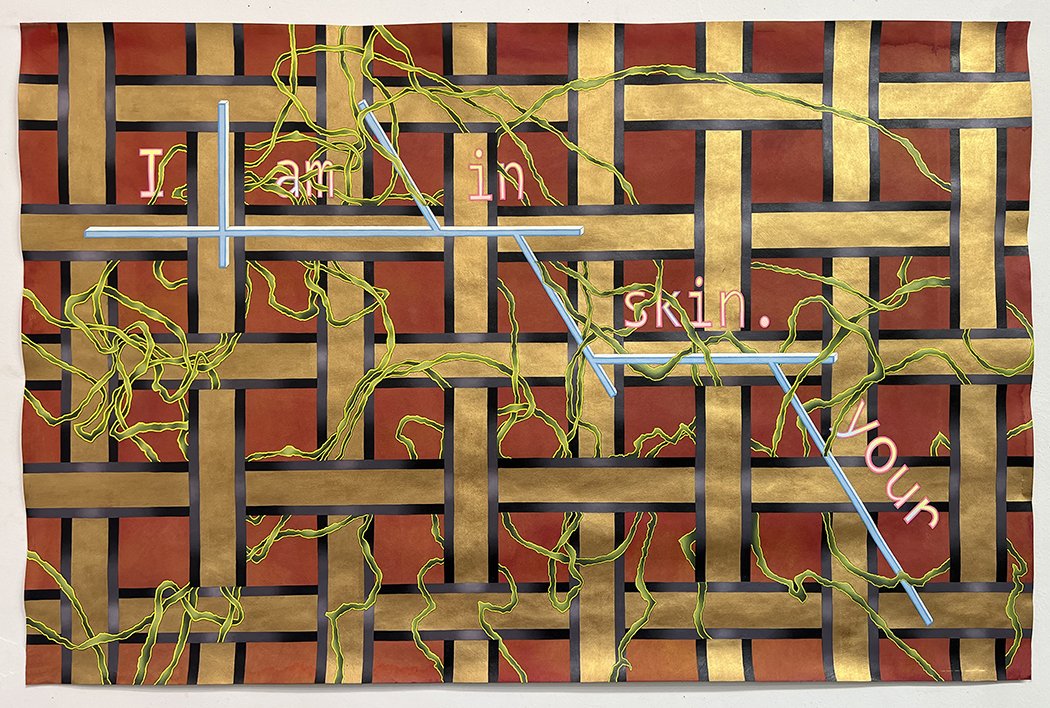

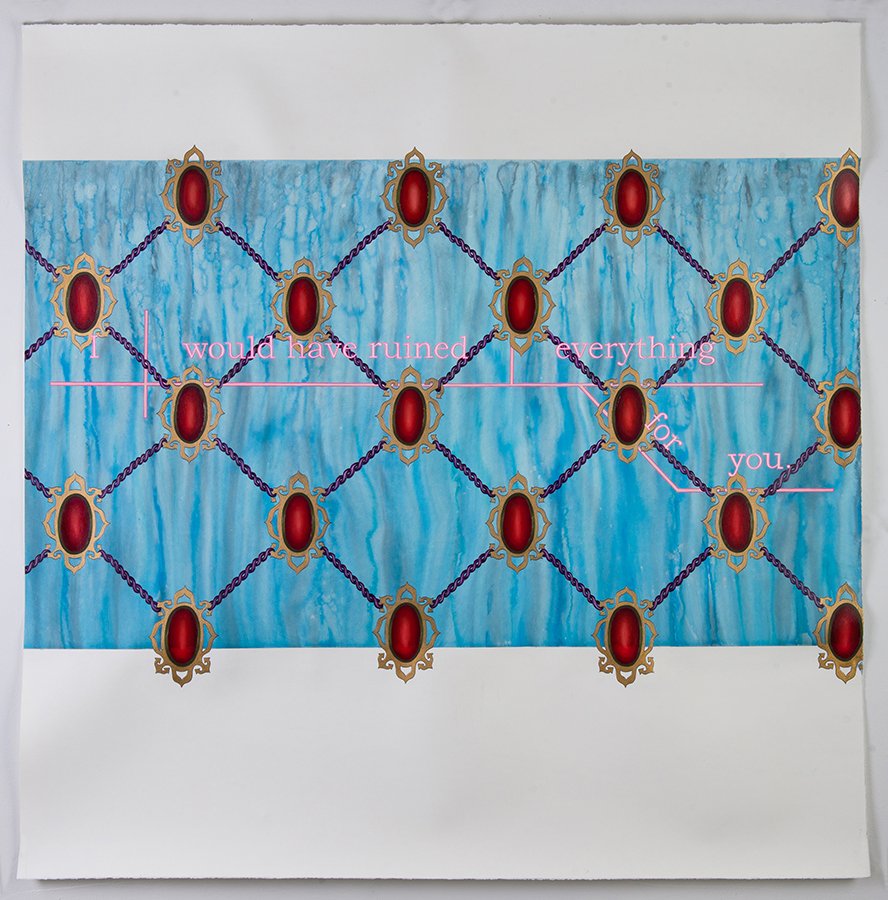

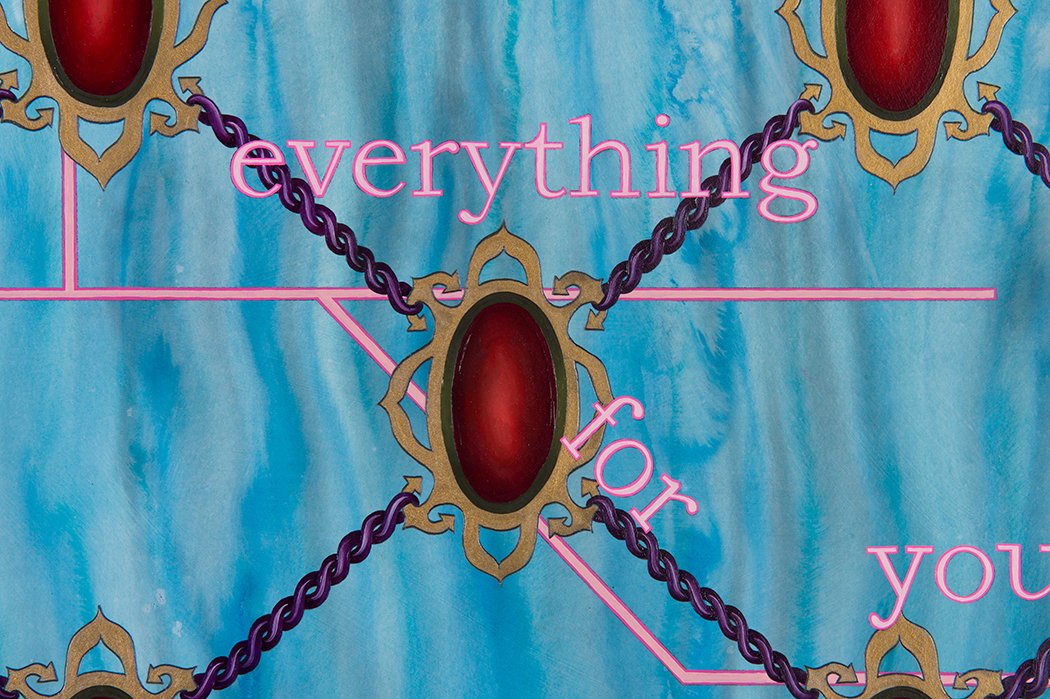

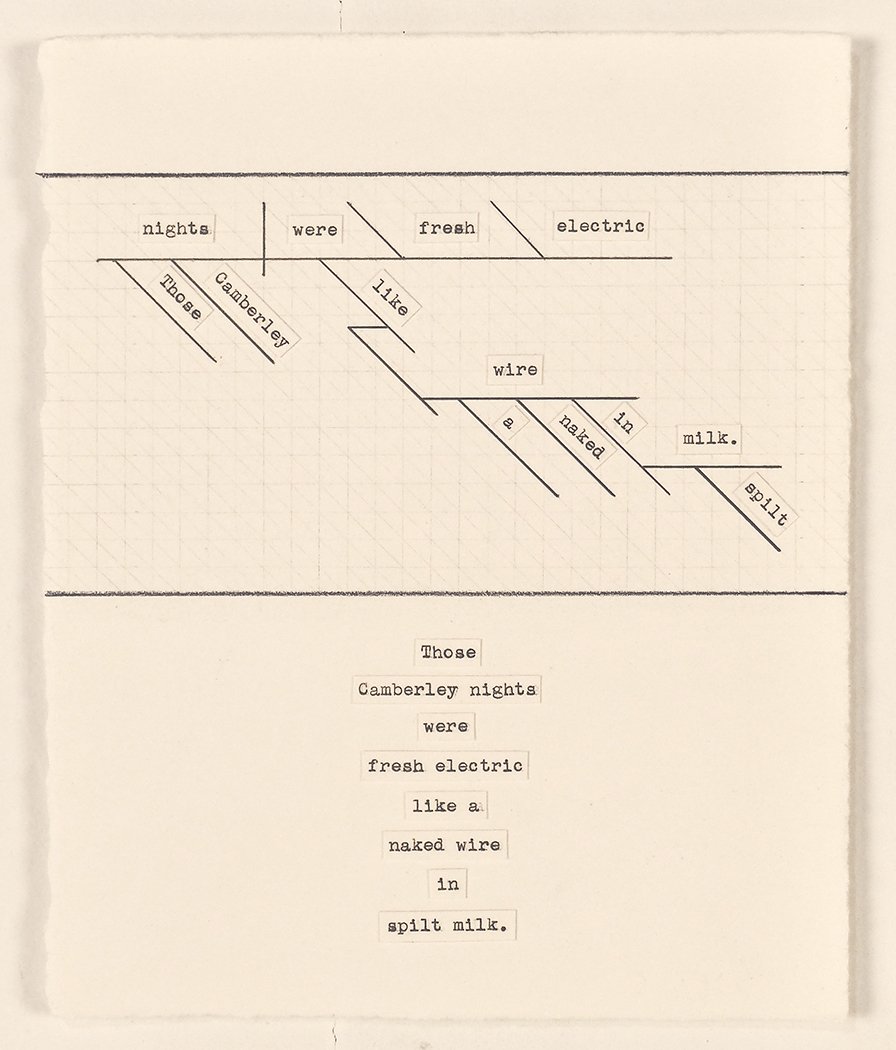

Alex Gingrow is a language-based artist who spends as much time crafting her sentences as she does painting the intricate patterns that accompany her text. Her sketchbooks are filled not with images, but with words, sentences, and fragments of narratives, all of which she uses to generate ideas for her paintings. She crafts words in the way that a sculptor uses a chisel, trimming away verbiage to arrive at the essence of an emotion or concept. Where most text-based artists aim for specificity in their language, Gingrow strives for lyric ambiguity. Her word combinations often have double meanings, allowing the viewer to interpret the piece according to their biases. In her current series, she presents sentences in the form of poetic flowcharts that emulate the cadence and rhythm of her writing. These verbal constructions are set against richly patterned backdrops that vie for our attention as they interweave with the foreground text. Gingrow’s ornate backdrops have an enigmatic vibe, reminiscent of wallpaper from a bygone era. The exquisitely painted patterns, combined with a disjointed narrative, create a tension that might infer an unreliable narrator. It’s likely that Gingrow would welcome our distrust, as her goal as both an artist and writer is to make us question anything that presents itself, and to examine the validity of our long-held beliefs.

MH: You work in various styles, but your paintings and drawings always include text. When did language start showing up in your work? What was the inspiration behind it?

AG: Language has always been present in my work. I remember around the age of eight making my first acrylic paintings and I would always include word bubbles or labels. I was gifted paint pens when I was a kid, and I wrote on everything. I’ve had times throughout both my development and career when I tried to literally paint over the text or obscure it to the point of abstraction, but text is how I generate ideas. I don’t sit down and sketch, I sit down and write. My mom and both my aunts were community college English teachers, so I grew up with language, literature, and grammar.

MH: What inspires your text? Can you describe your writing and editing process? Sometimes it’s very personal, other times it can be controversial.

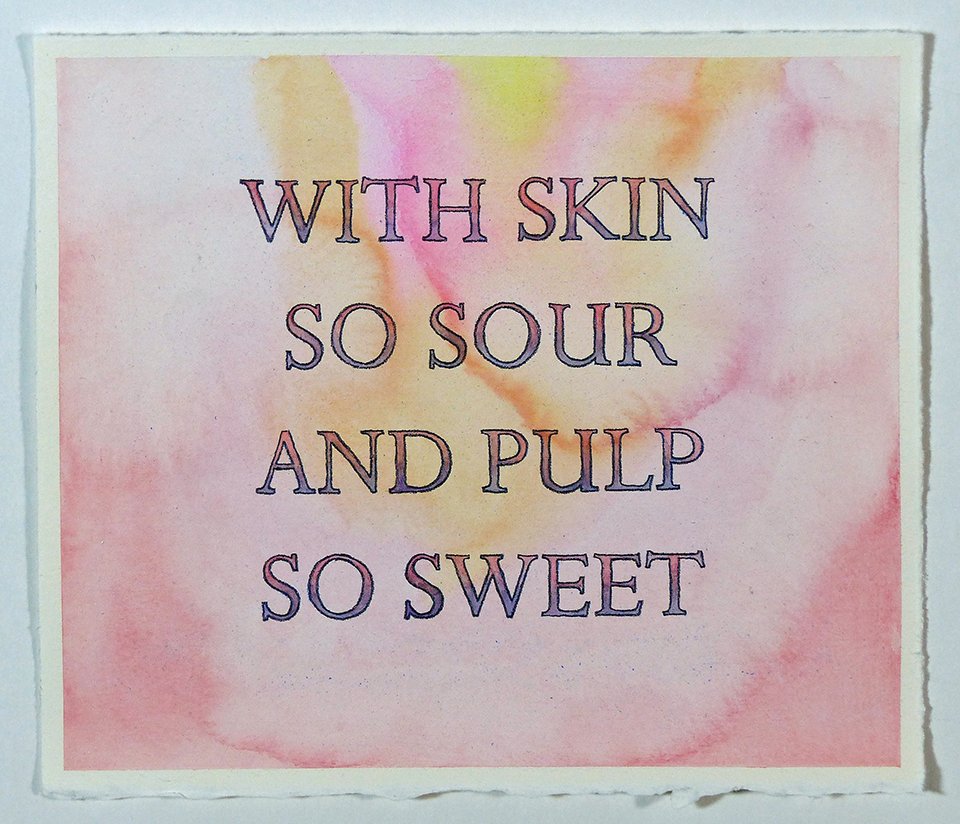

AG: It does vary a lot. When I lived in the city, the text was inspired by the tempo and cadence of walking. I generated ideas by walking and looking, and the ideas seeped in naturally. I’m also inspired by African American literature, which was my focus in undergrad, because for a while I was an English major as well as an art major. There’s something about the innate tempo in African American and Caribbean literature that has always resonated with me. But I don’t think in pictures, I think in words. Sometimes a sentence will come to me, and it’s done, it’s perfect. Other times I generate pages and pages of stream of consciousness writing, then I do an intense editing process where I go through and underline what I call the nuggets. Then I take those out and basically sketch with them. It’s almost like concrete poetry, where the verbal and the aesthetic are intertwined.

MH: Painting is like poetry in that it communicates by suggestion or metaphor. Adding text allows the artist to convey something with more precision. Is this a consideration in your use of text? Are you looking to be more specific?

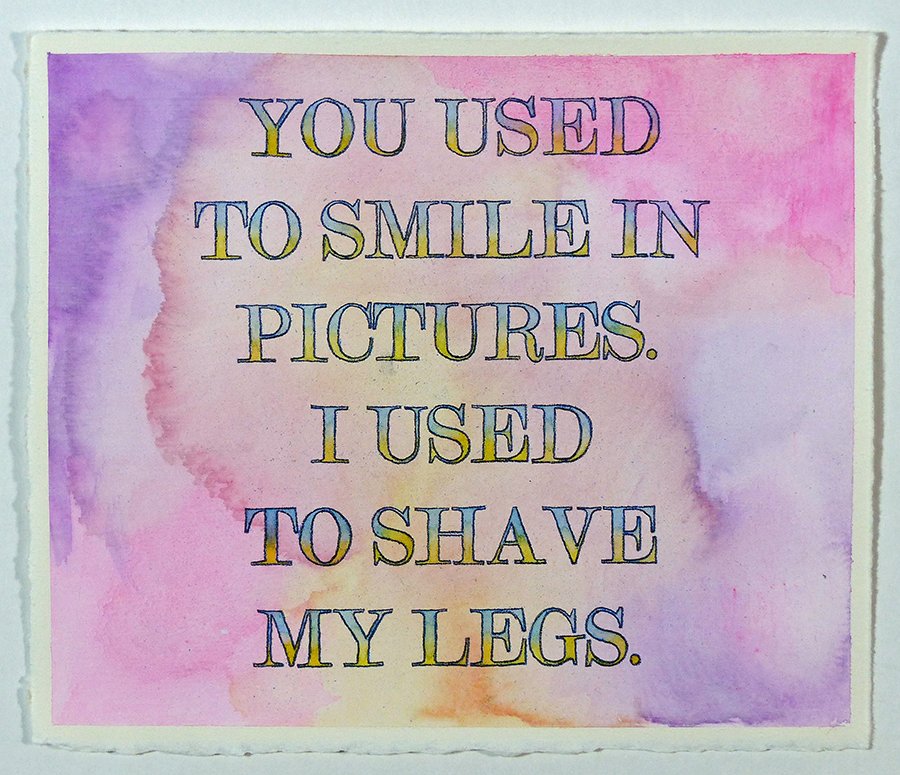

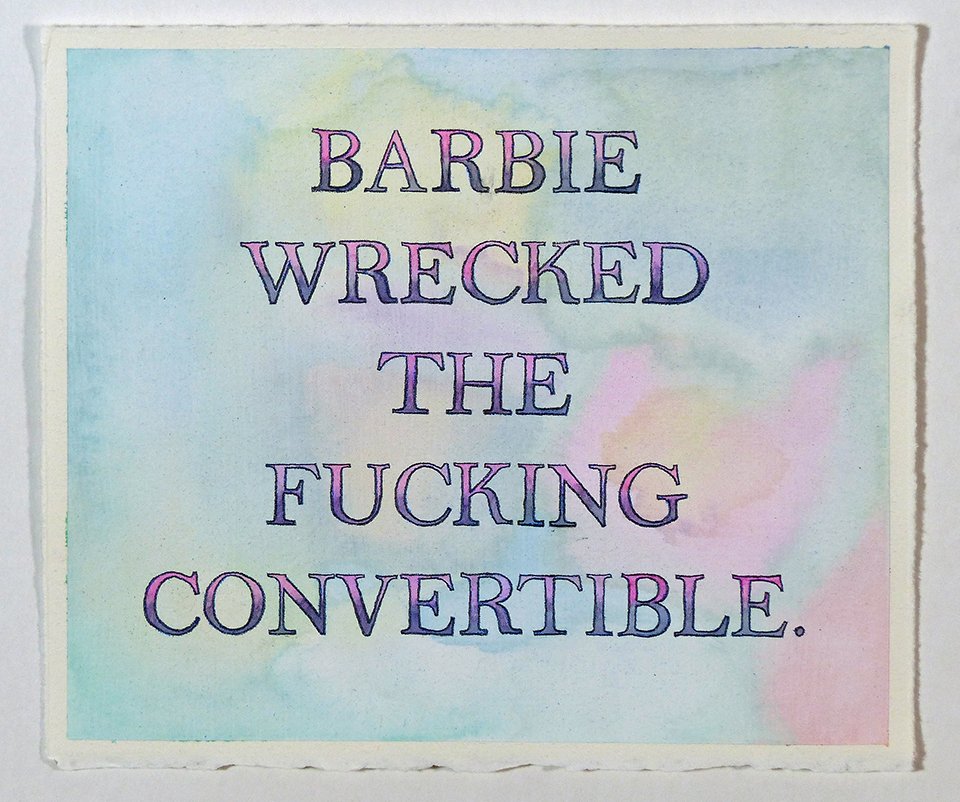

AG: Actually, what I’m striving for is ambiguity. There’s something specific about the nature of language and words, but I don’t want to be overly didactic. A lot of the text and phrases that I use have double meanings, and their interpretation depends on what the viewer brings to it. So as I’m generating words, I think about competing ideas and what the text brings up.

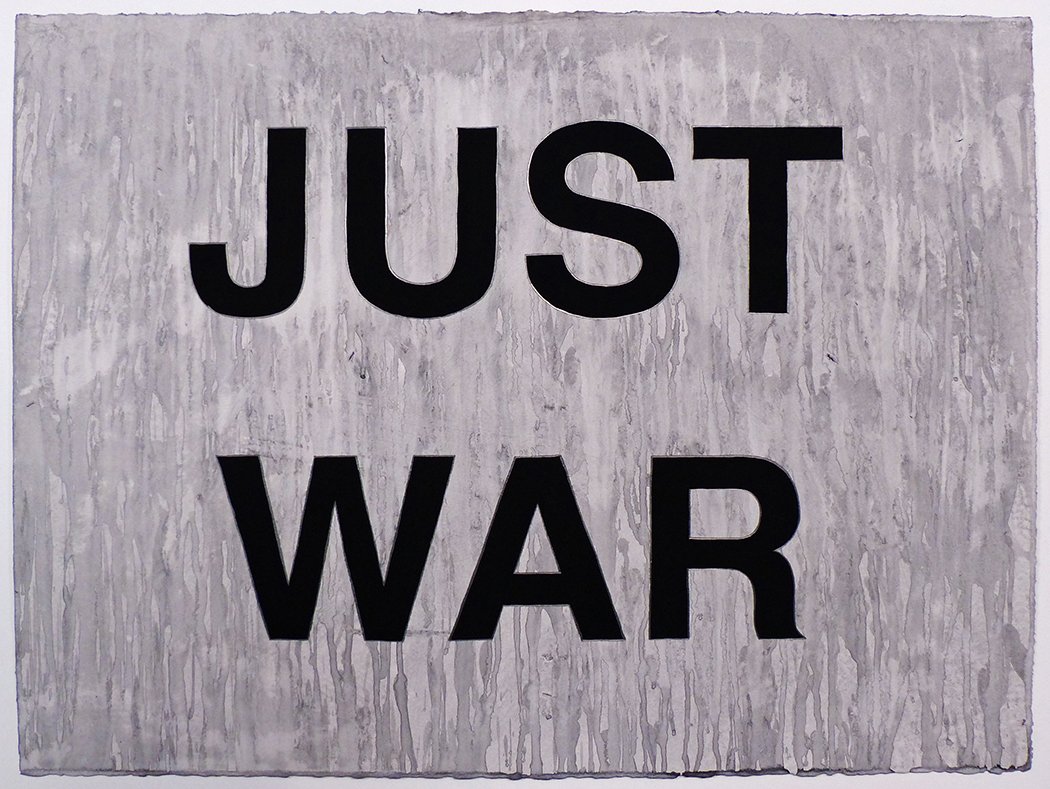

MH: Here’s an example of interesting ambiguity. A piece contains two words: JUST WAR. I read it as “It’s just war! Get over it, snowflake.” But I could also see someone reading it as “It’s a just war, because the Ukrainians are defending their territory”. Either way, it could be interpreted as an incitement to war. What are your thoughts behind this series?

AG: That’s exactly the ambiguity that I’m embracing. And I think a step beyond that is not just the interpretation of the language, but what is war, anyway? What is valid aggression? How do we determine that? And again, I’m not approaching it didactically. I don’t have an answer for that. I’d never want to be a leader of a country because I wouldn’t want to make that decision. Was World War II justified? What does that imply? Who are we to decide? My concern is for humanity to think longer and harder about those questions.

MH: I think it was Kurt Vonnegut who said that war is never justified. It’s not worth the death toll; we should just surrender to a new regime and carry on with our lives. And that’s arguable as well. But I have a question about this piece. If someone say on the far right took your piece “JUST WAR” and appropriated it as a call to arms or used it in a way that’s not in alignment with your sensibilities, how would you feel about that?

AG: I mean, of course I’d have an absolute fit about that, and fight it tooth and nail.

MH: But in a sense you wouldn’t have an argument because there’s this ambiguity. The larger question is when an artist makes a work of art and it’s completely misunderstood or misrepresented, what do we do about that?

AG: It’s a great question, like the Dana Schutz piece in the Whitney Biennial, the painting of Emmett Till. I followed that closely and understood both sides of the argument, and I think the only solution was the dialogue around it. We need to talk about these things and try to see the other point of view. Communication is key, understanding someone’s intent and where they’re coming from, even if you disagree.

MH: Your text is often poetic or fragmented. In a sense, you’re layering poetry on top of poetry, giving the work an enigmatic edge. Does it bother you if someone doesn’t get your work in the way you intended?

AG: No. If I thought I could control that, I’m in the wrong business. I mean, it’s not up to me to make someone do something. I like to provide the hand, I want to give an offering, and if someone is open to accepting that, then come on board, but I can’t control what other people interpret.

MH: How do you think about the background? In some pieces it’s minimal, making the text easier to read. But they lack the visual appeal of your more ornate backgrounds. Do you use this patterning to draw the viewer deeper into the painting?

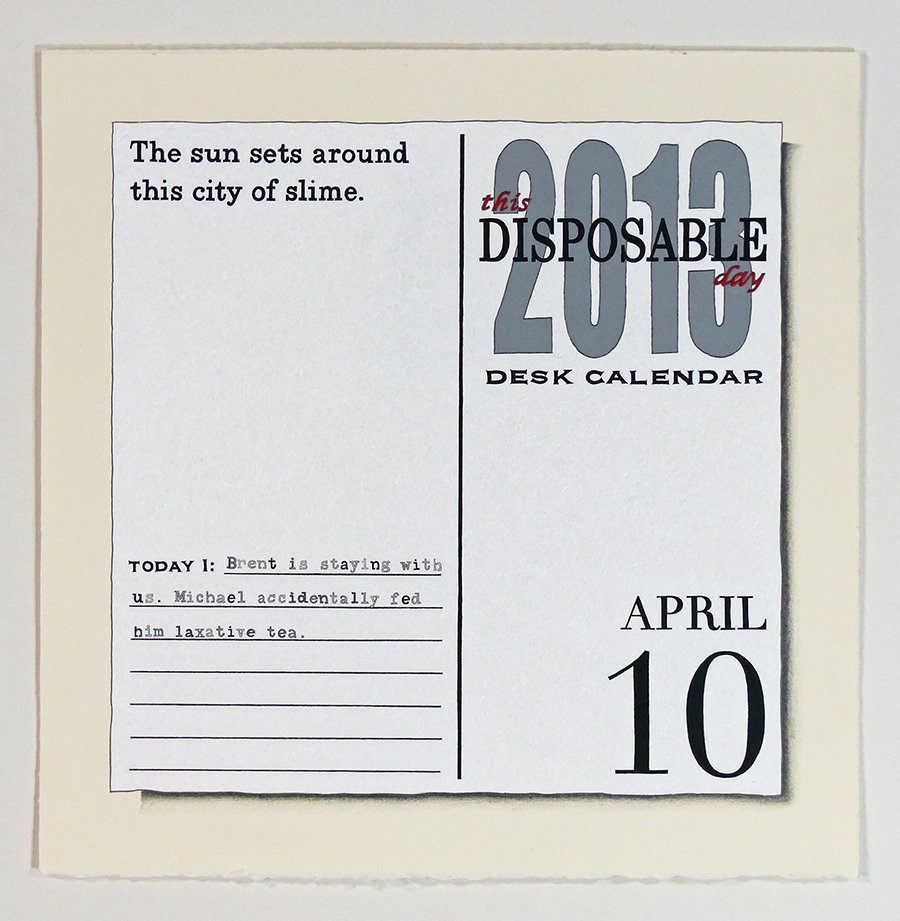

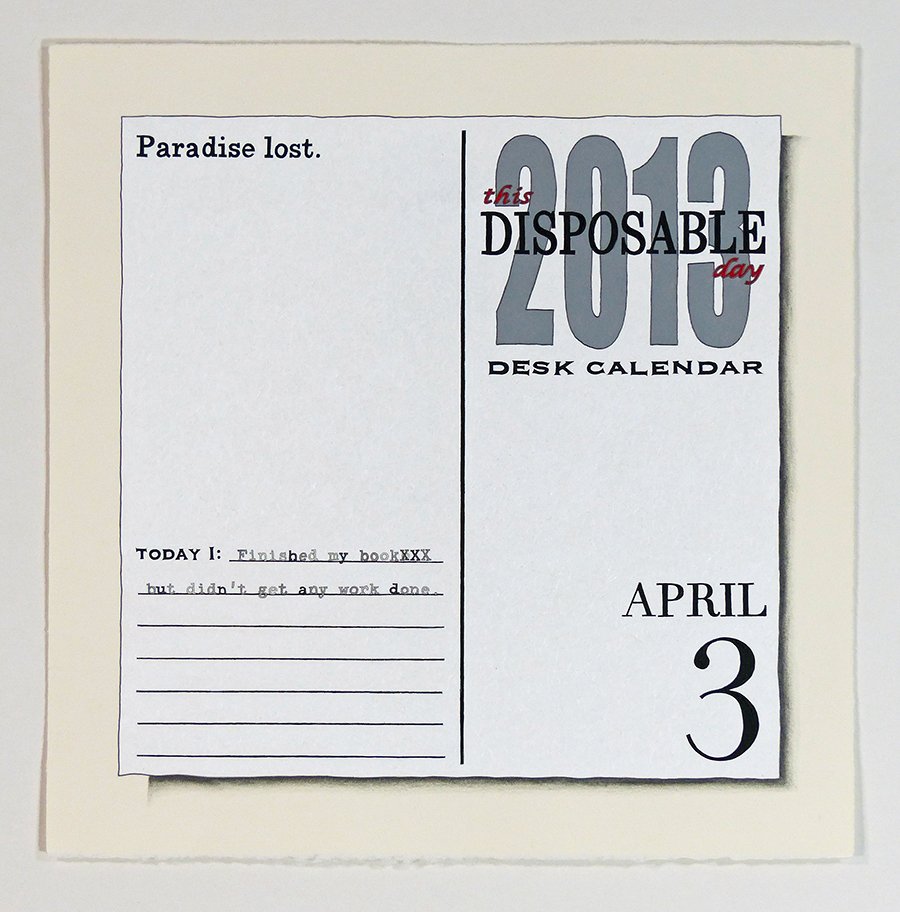

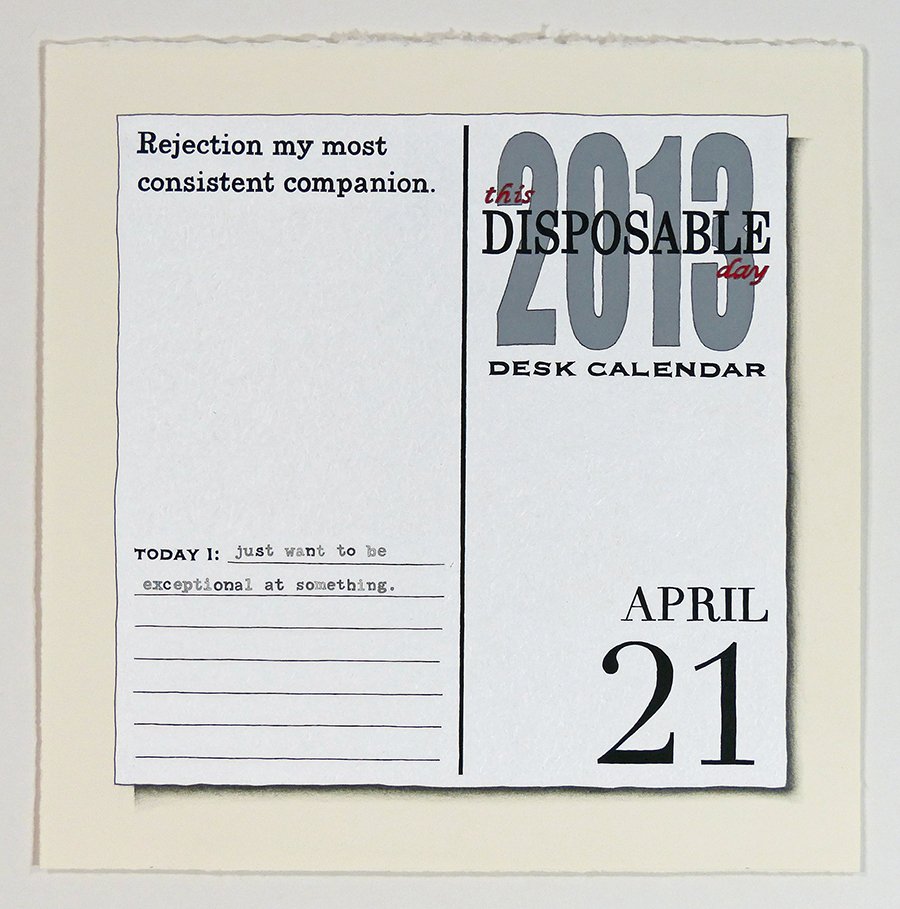

AG: The patterning in this recent body of work was born out of the pandemic. I was home for two years with a young child and an older house that we’d recently moved into, and I began noticing the upholstery, the wallpaper, the weird patterns from the 80s. Like the cadence of walking in the city, I found that those patterns of domesticity have their own tempo. Their repetition and patterning create a meditative trance for me so I can slip into thinking about stories, words, and memories. I think that’s what has inspired my highly textured and patterned backgrounds. In older works like the Provenance and Calendar series, the backgrounds are white brush marks, very repetitive with a size 0 brush. From a distance it just looks like a white backdrop, but when you get up close, you’re rewarded with the hand of the artist, these tiny brush marks that you want to touch. So background has always been important for me as a platform for the text, but it’s not subsequent to the text; it is its own reward.

MH: The baroque background often stands in contrast to the stark statement in the foreground. This juxtaposition is interesting, especially because the filigree makes it harder to read the text. Why did you go in the direction of making the text harder to read? Was it a literary or a painterly decision?

AG: Definitely more of a painterly decision. I’ve found that in working with text over the years, there are some people who don’t like to read. If they see text in a work of art that’s slightly longer than a meme, they don’t have the attention span to spend time with it. I want people to be beckoned forward, and then once they get there, things start to unfold. It’s like getting to know someone. The closer you get, the more conversations you have with them, and you begin to create a connection. That’s what I hope happens with my work; that’s the goal.

MH: Is that the goal rather than making a statement with your work? Even an ambiguous statement?

AG: It’s the initial goal because it foretells the coming of a relationship. I don’t want my piece to decorate a room, I’d like the collector to have a relationship with it. I want to make work that someone will get lost in every now and again, like a springboard into their thoughts and memories.

MH: You mentioned that you’re also a writer, which comes as no surprise. Why does your creativity appear in its current form? Why visual art instead of literary pursuits?

AG: I would prefer to be a writer but I’m too scared. I’ve thought about this a lot. I’ve started so many novels, but I abandon them after a while. I think it’s because my mom proofread and edited my papers when I was a kid, and it was brutal. Brutal! [laughter] There’s something so raw about writing and when someone scratches that wound, it just hurts too much.

MH: Ha! Interesting. You think the publishing world is more brutal than the art world?

AG: To me. Perhaps not to somebody else. I mean, you can tear apart my painting process and technique all day and I can deal with it; it feels like you’re just scratching my skin. But if you tear apart the writing or poetry or narrative, it feels like you’re scratching my heart.

MH: How awful. Have you heard other writers express the same thing?

AG: I’ve never asked anyone before. But that’s only a small part of it. The writing is so direct and personal. It’s the child in me shrinking away from criticism. But if I paint the text and interweave it with aesthetic options, it’s like a protective cloak, and I can deal with it.

MH: Do you aspire to write a novel, or are you content with your current writing process? Is it fun to craft succinct verses? I think of the novel “Baby Shoes” by Hemingway, composed of six words: “For sale: baby shoes, never worn.” Your work has that reductive quality.

AG: I love the challenge of writing a novel, but at this point it's more aspirational than actually in progress. I’ve drafted it, I’ve started it, I’ve rewritten it, I’ve edited it, rewritten it again. We’re building a new studio on our property and it’s going to have a writing corner, so we’ll see what happens.

MH: Your literary constructions are so tight and pared down that I compare them to sculptures. Does it ever feel like you’re sculpting with words, reducing big ideas to their barest essence?

AG: I love that idea. I’ve never thought of it in that way because I’m so non-three-dimensional, but it’s not about dimension at that point, it’s more about crafting. It’s both building and chiseling away.

MH: Yes, a novel is about building a narrative, but what you’re doing is more about reduction, trimming away the excess.

AG: On my current piece I spent a week chewing on the difference between the prepositions through and on. “Sinister steps through frozen leaves”, or “Sinister steps on frozen leaves”? I kept writing it both ways, trying to decide between the two words.

MH: Which was it?

AG: Through.

MH: I like through. It has movement. “On” feels static.

AG: Yeah, but do the sinister steps continue? Or do I need the oppression of “on”? Are they passing or settling? [laughter]

MH: It seems that you’ve found the perfect medium for your sensibilities and skills. You can write in a nonlinear style, express a condensed statement that can be challenging to the viewer, and paint it in a way that’s visually seductive. Does this check all the boxes for you? Are your writerly urges satisfied in your studio practice?

AG: For the most part, yes. I wish I journaled more, because I think a lot comes out of journaling, both in the process and going back to it later. But the creative writing is absolutely satisfied in my studio practice.

MH: I find it interesting that most text-based art is subversive in some way, yours included. Would you agree with that generalization? And if so, why do you think this is the case? Why does the use of language in visual art incline toward subversion?

AG: In the fine arts realm text almost has to be subversive, otherwise you’re competing with advertising, memes, and direct sales or hooks. So when an artist chooses to use text in their work, they have to skirt around that kind of thing so they don’t run the risk of being one-dimensional.

MH: Can you give me an example?

AG: “Bless This Home”. It’s something you could get at the art section of Target or Michael’s. It’s a quick delivery, and has one interpretation.

MH: Artists have a propensity to rail against the status quo, and text is often added to a work of art to clarify or intensify an opinion. So it’s easy to see how text-based art would be provocative. Is it important to you that your work elicits a reaction? What would be the ideal response?

AG: I think it’s important to distinguish between artists who use text in a piece, and an artist who uses text as their work. I would put myself in that latter category. My work is the text, and everything else is the scaffolding that supports it. As far as the reaction, I want to present something for the viewer to chew on. In one piece from my Calendar series, I wrote, “I want to be the kernel of popcorn in your teeth.” Maybe it’s an annoyance, but it’s there. I want someone to enjoy the work on an aesthetic level, but what I want more is for someone to interpret the text in their own way and consider it from all different angles. I want the text to exist as part of an examination of the human condition. The goal is for the text to resonate with someone from a completely different demographic.

MH: Honestly, you sound more like a writer. Because a writer talks about creating these narratives that tap into the human experience. But then there’s this seductive visual element that’s sort of a delivery system for your writing. You really do have a foot in both worlds.

AG: It’s a hard place to occupy sometimes in the art world because I don’t want my work to be a solely aesthetic experience. When I go on residencies, I prefer to hang out with the writers and poets rather than the artists.

MH: Would you ever consider being a writer who has a painterly style?

AG: I wouldn’t rule it out. I mean I love doing these tiny, intricate paintings. I find it so satisfying, spiritually fulfilling, meditative, but it’s getting more difficult. I’m often hunched over doing teeny detail work with a super tiny brush, and at the end of the day my body hurts and my eyes are strained. So it may be an organic progression toward writing at some point.

MH: In a broad sense, do you feel that you’re undermining something in your work? And if so, what?

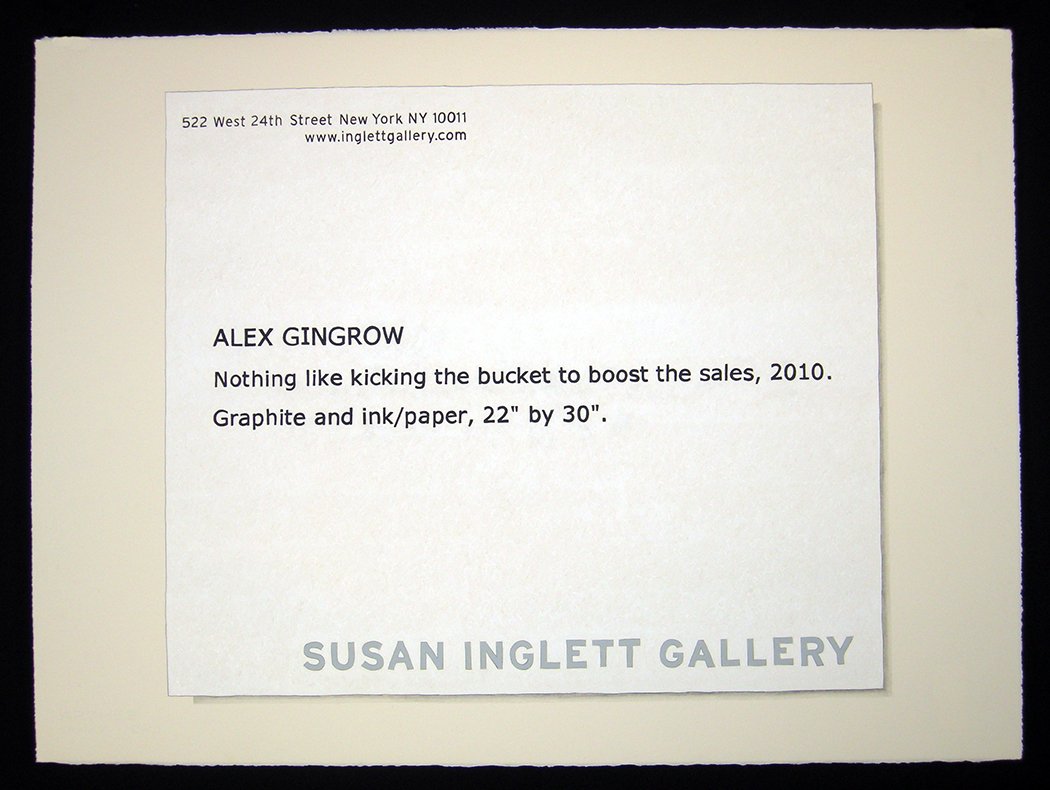

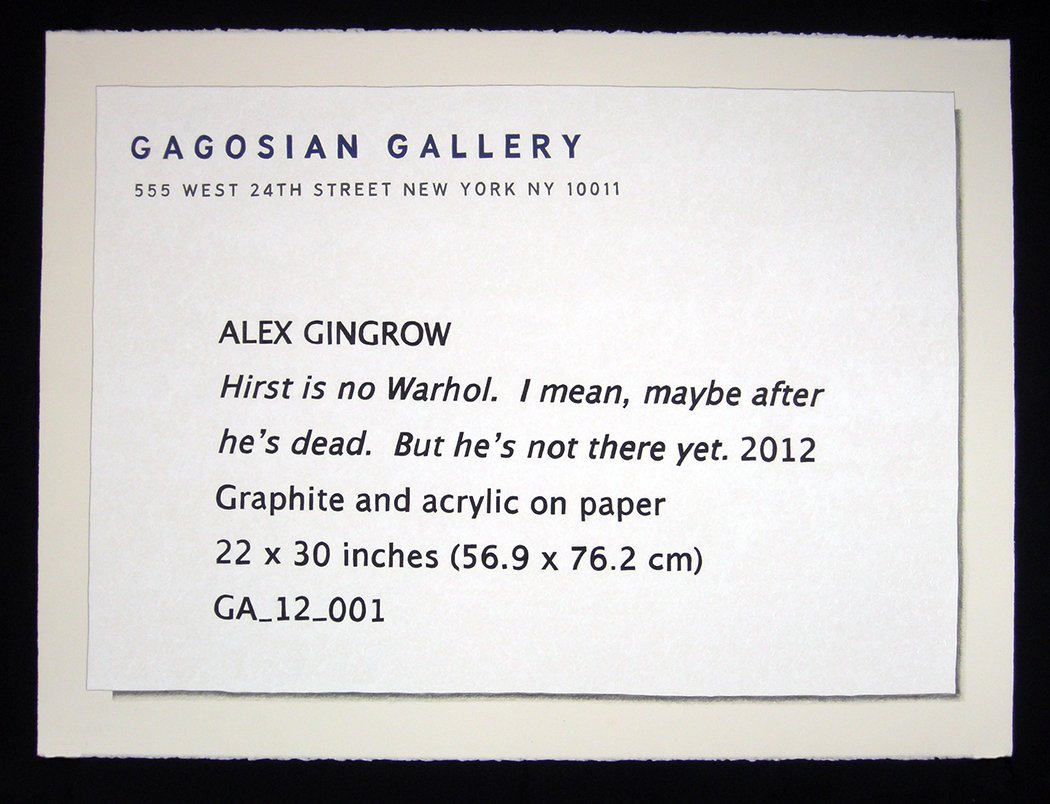

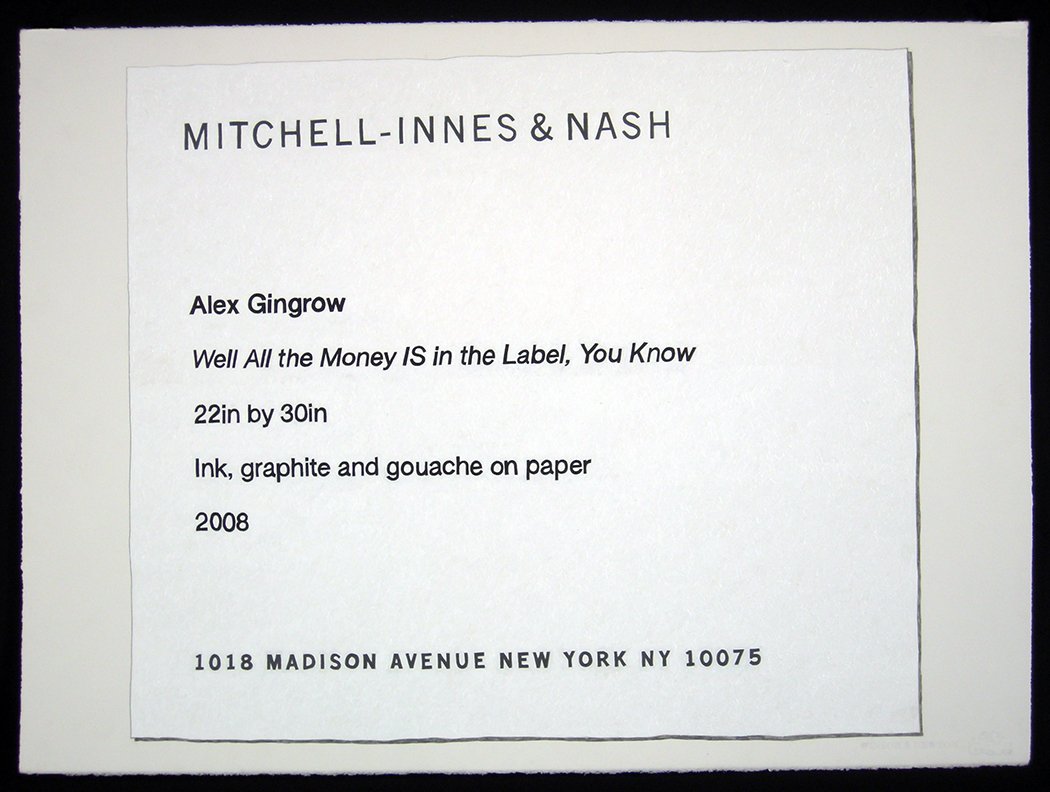

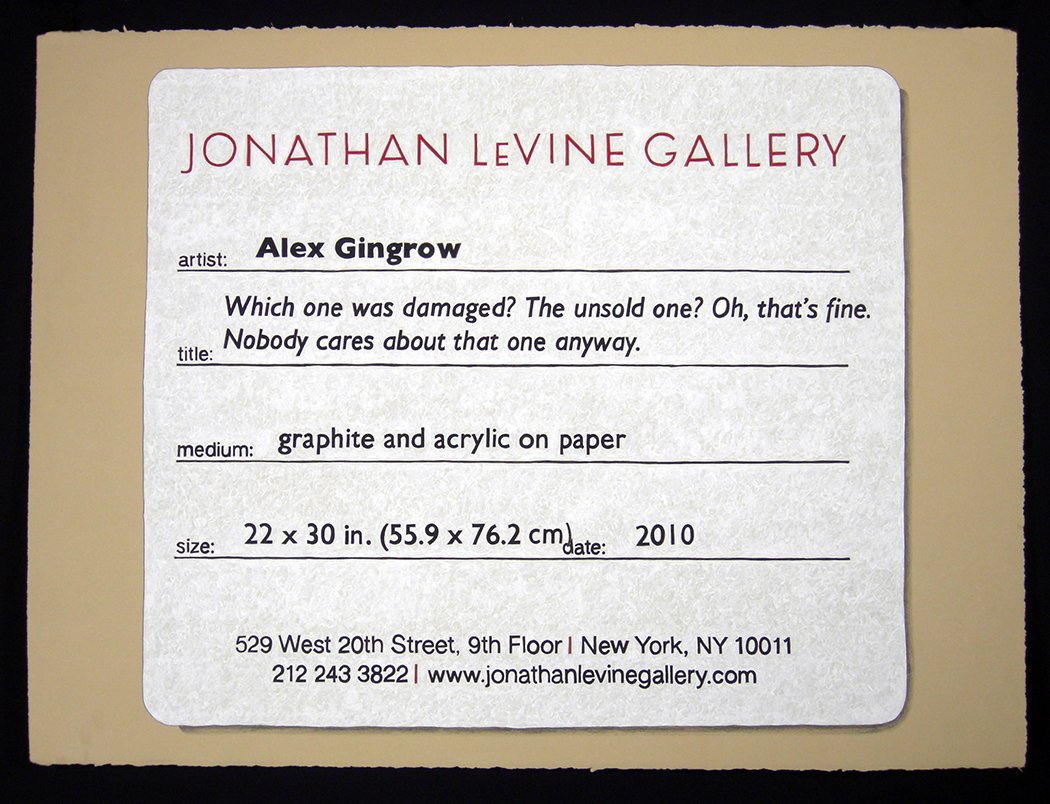

AG: That’s an interesting question. In the Provenance labels, there was some intentional and more obvious subversion, which was the subversion of the gallery world, the art world. I would say that there’s some personal subversion in some of the stories that I write and tell, things that I’d never admit to anyone, so maybe that energy invades a piece. I’ve always had a rebellious streak, so perhaps some things come across that way, but it’s not anything that’s intentional. I grew up in Tennessee in a very liberal, democratic, queer family, not anything typical for that region. I think I’ve always realized that I don’t have to fit in, and I’m happy to live that way.

MH: In general, does art undermine something?

AG: Anyone who lives in the world as a critical thinker is undermining and questioning the status quo, right? I mean, that should be our job! One of the most beautiful things about being an artist is the access to everything, the permission to explore anything. That’s not encouraged in traditional society. You wake up in your little box, you stay in your lane, you go to your job, you stay in your socio-economic strata. There are these boxes that are easy to fit into, and our job as artists is to question everything. So yes, there’s inherent subversion in that.

MH: Do you ever use the text as a means to extract or exorcize something out of your system? Can it be cathartic in some way?

AG: I think about that often. Sometimes I think I hold onto some stories so I can keep mining those inappropriate, discomforting things. Maybe I keep going back to get that human response and then exploit it in the text somehow.

MH: Rilke said he never wanted to go into psychotherapy because he didn’t want to exorcise his demons. They were his material.

AG: There’s a lot of validity in that. There are intense topics that I’ve dealt with numerous times across numerous series, and yet they’re still in there. They haven’t gone away, so maybe I need them.

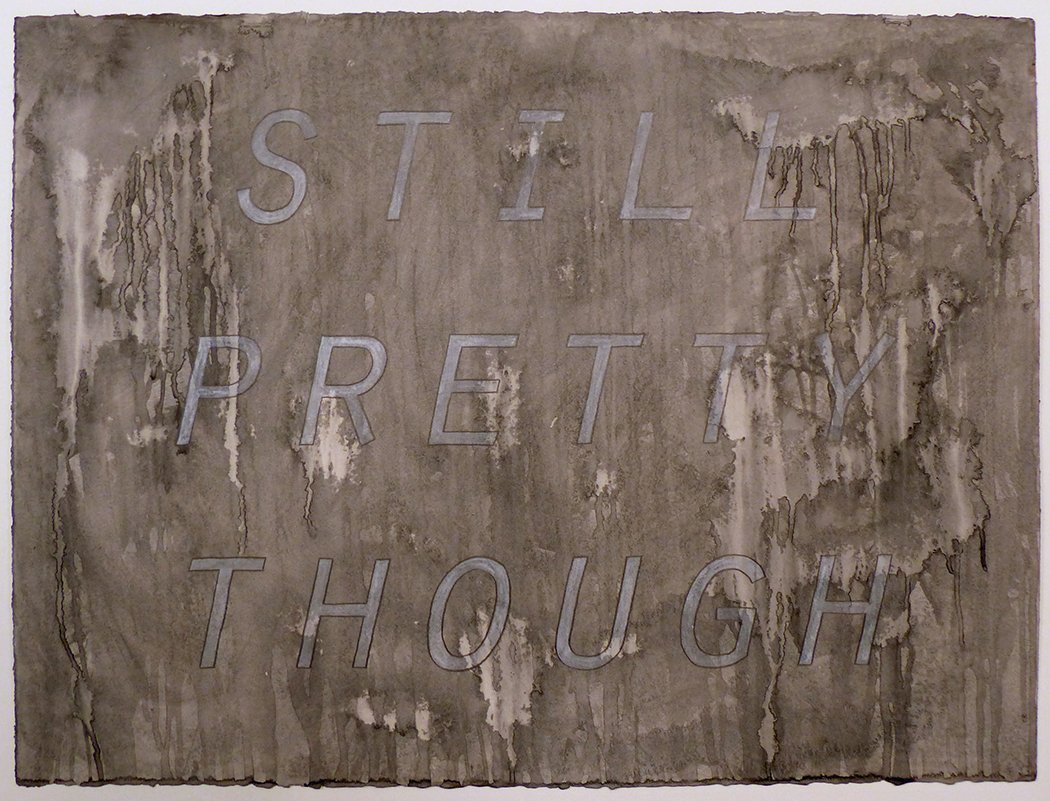

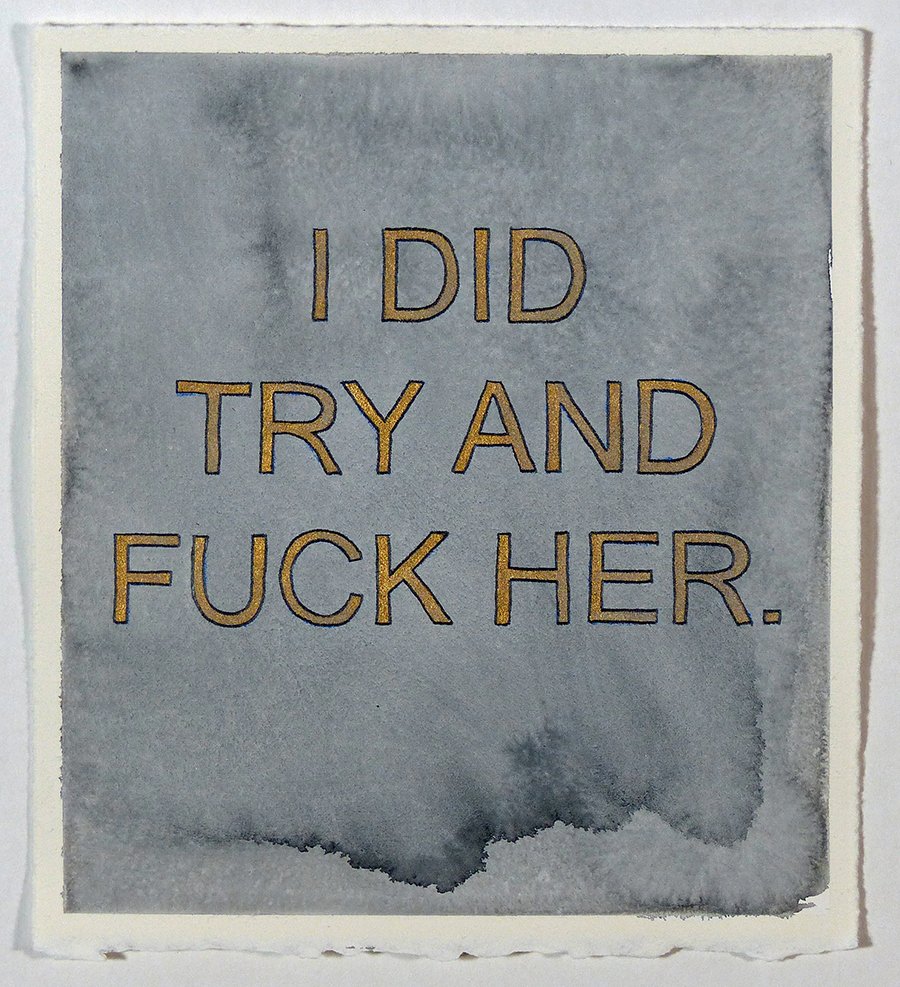

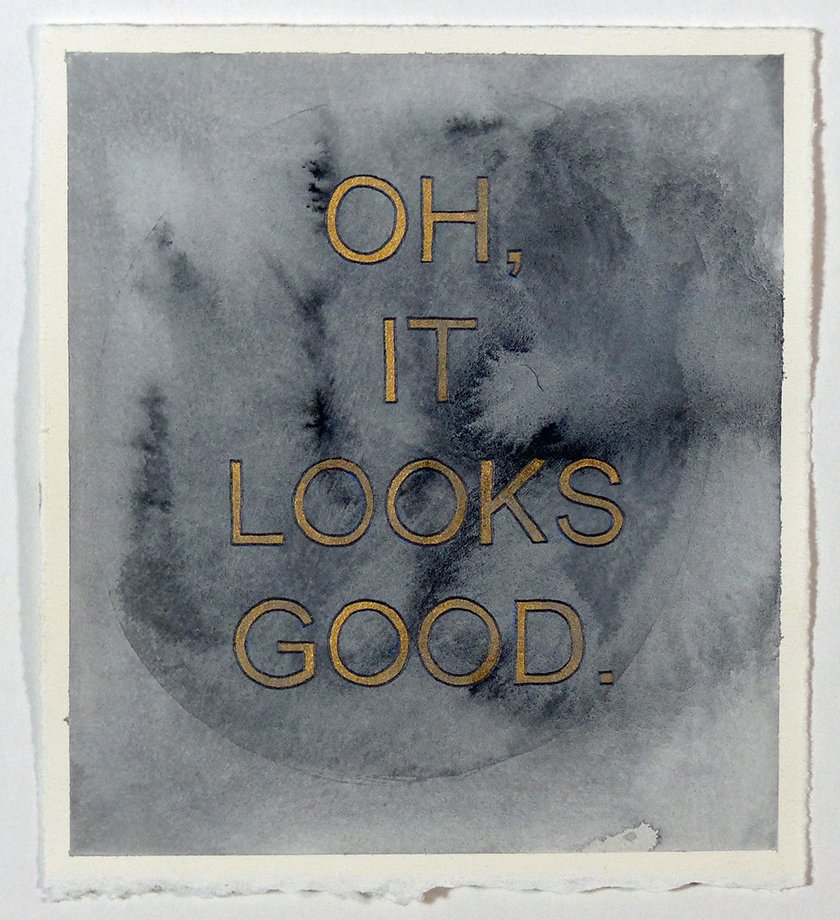

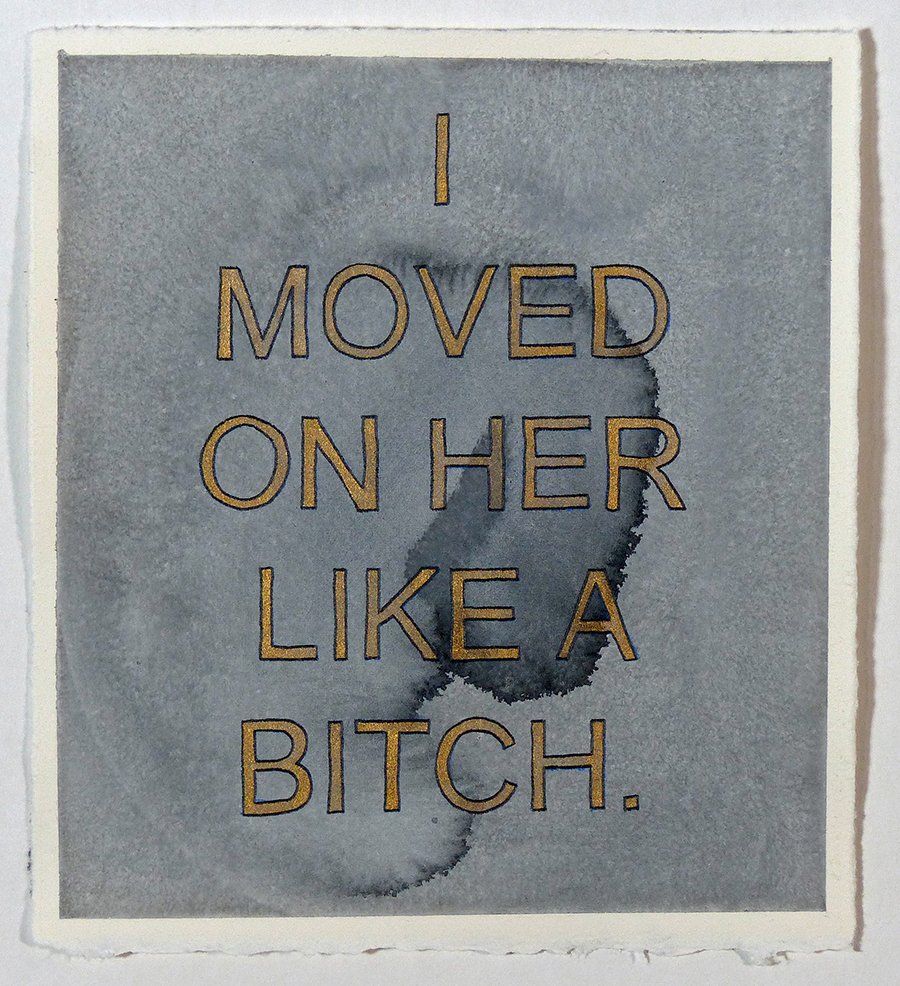

MH: On a personal note, it was difficult for me to look at your Trump series. It felt like I was tapping into a dense energy, and I didn’t want to give it any of my time. That’s a powerful reaction to a piece of art! How does it feel to bring this kind of toxic energy into your studio?

AG: Those are excerpts are from the Access Hollywood video. There are fourteen pieces total in that series. I don’t want to spend a lot of time on him, but I felt like I had to make those at the time. I had to see how they read in a year, in five years, in ten years. They’re probably never going to sell and that’s totally fine; that’s not what they were about. But they’re part of our collective American experience and I felt that they were important. The American people elected this person, and we deserve to see his words and be ashamed of them.

MH: Do you ever see yourself leaving text behind, or would that be like declawing a cat? Would it be easier to leave painting behind and express yourself purely through writing? Or are text and image so intertwined in your work that you can’t feature letting either of them go?

AG: I don’t foresee letting them go but of course I’m open to any natural evolution. Writing will always be a part of me, and I just enjoy the process of putting paint on paper. The writing is the actual art, or what I think of as the manifestation of my own spirituality, and making the work is the physical act of devotion or spiritual practice. Coming to the studio, mixing pigment, cleaning brushes, throwing ink on paper – that’s my form of processing and worship and devotion. I can’t imagine ever abandoning that.

MH: What’s the best part about being an artist?

AG: The life! To get to be creative every day, to have the permission to explore anything. If I’m interested in quantum physics or astronomy or mythology, or if I’m inspired by nature walks, I get to be curious and explore it all. How great is that? And then there’s all the people you get to know on an interesting level, not just talk next to the water cooler. It’s the freedom of spirit. I don’t know what else I could do.