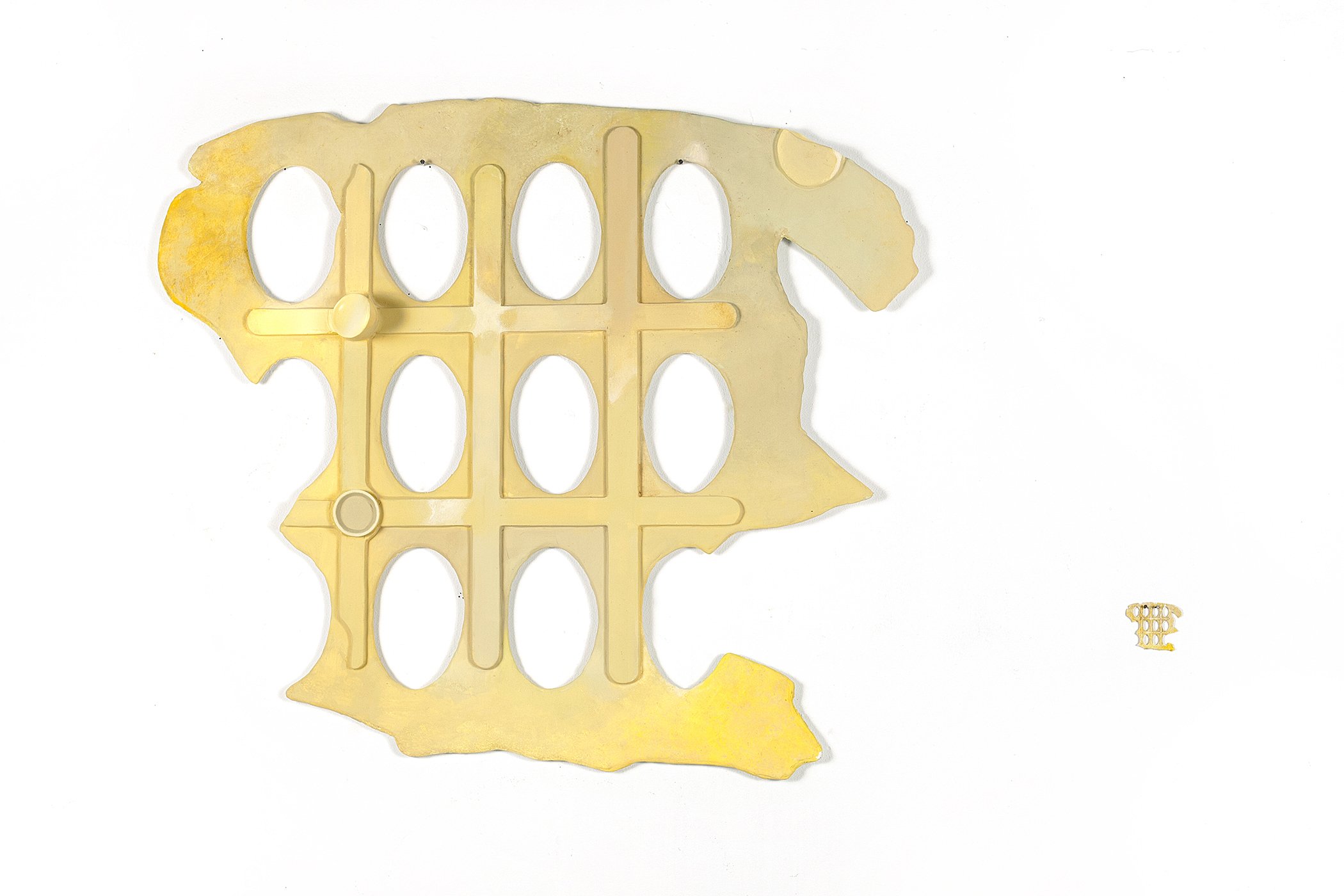

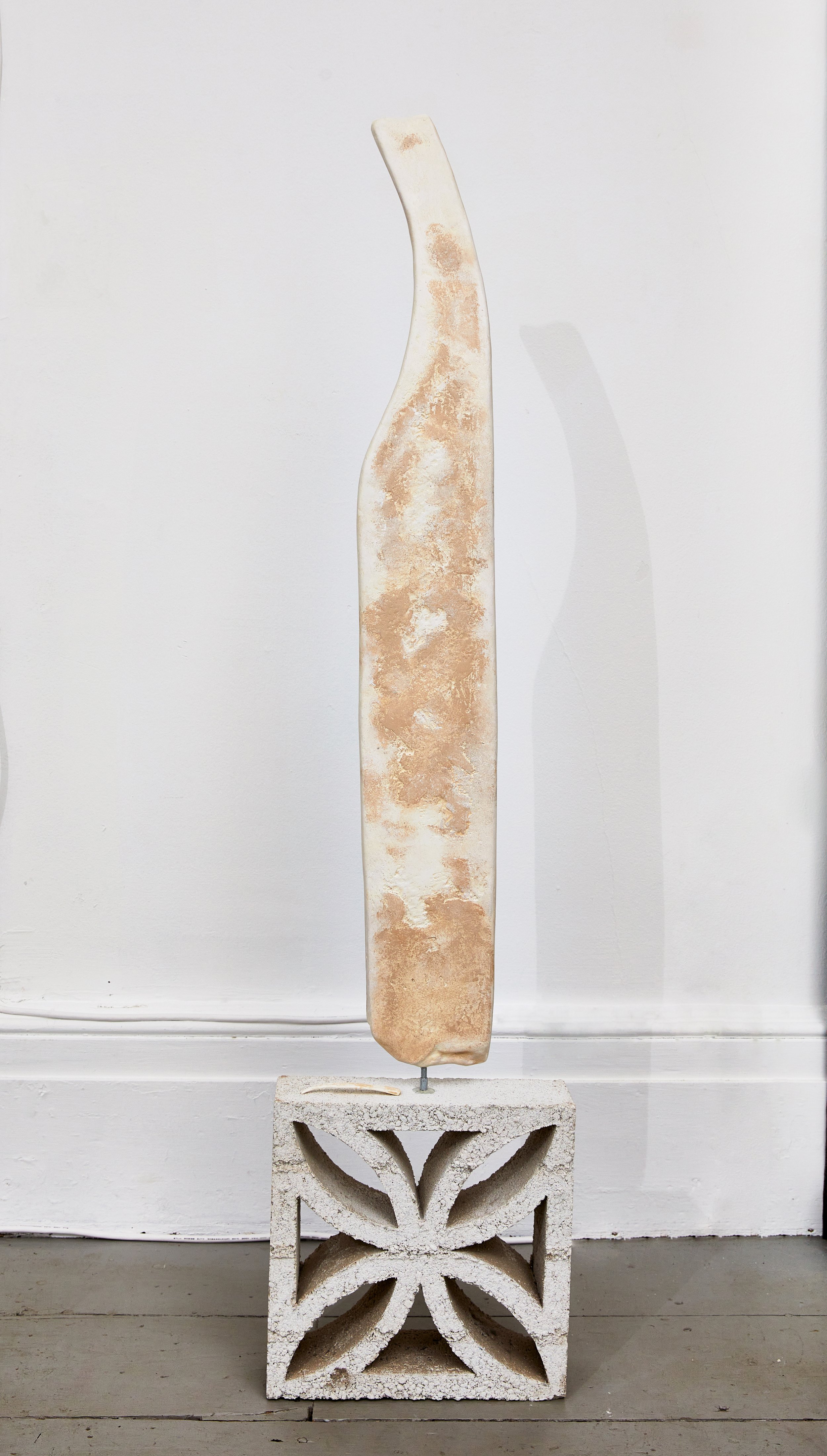

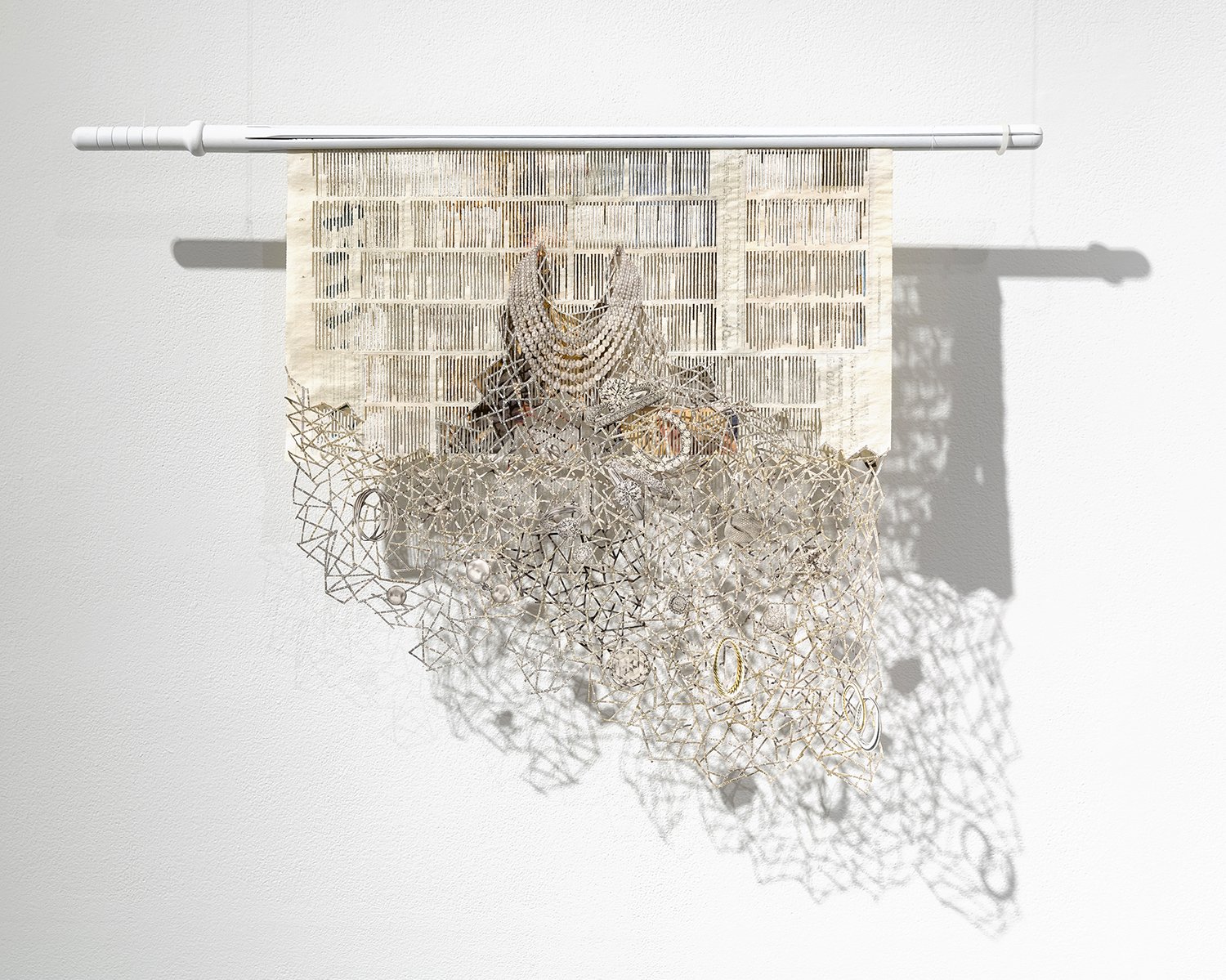

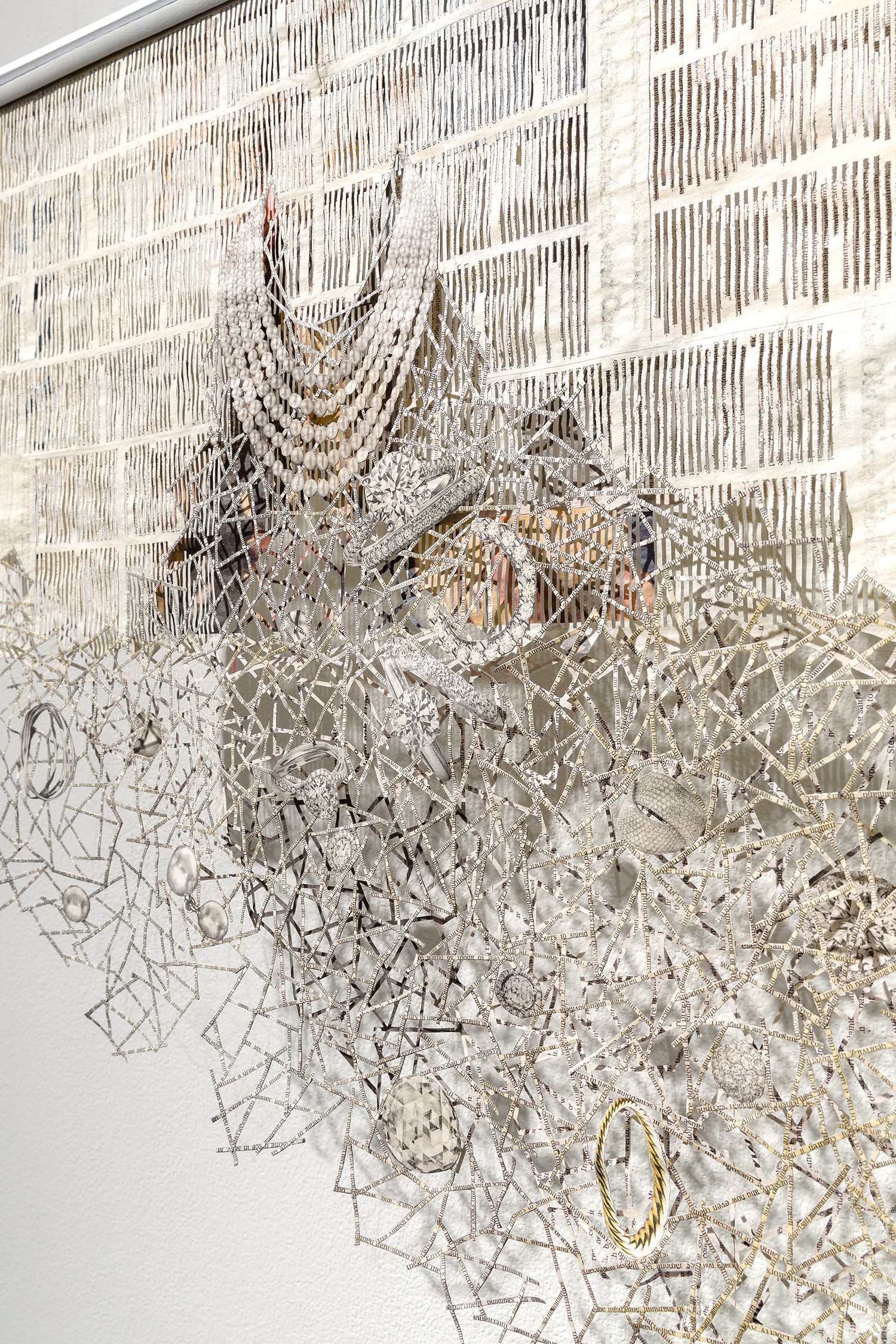

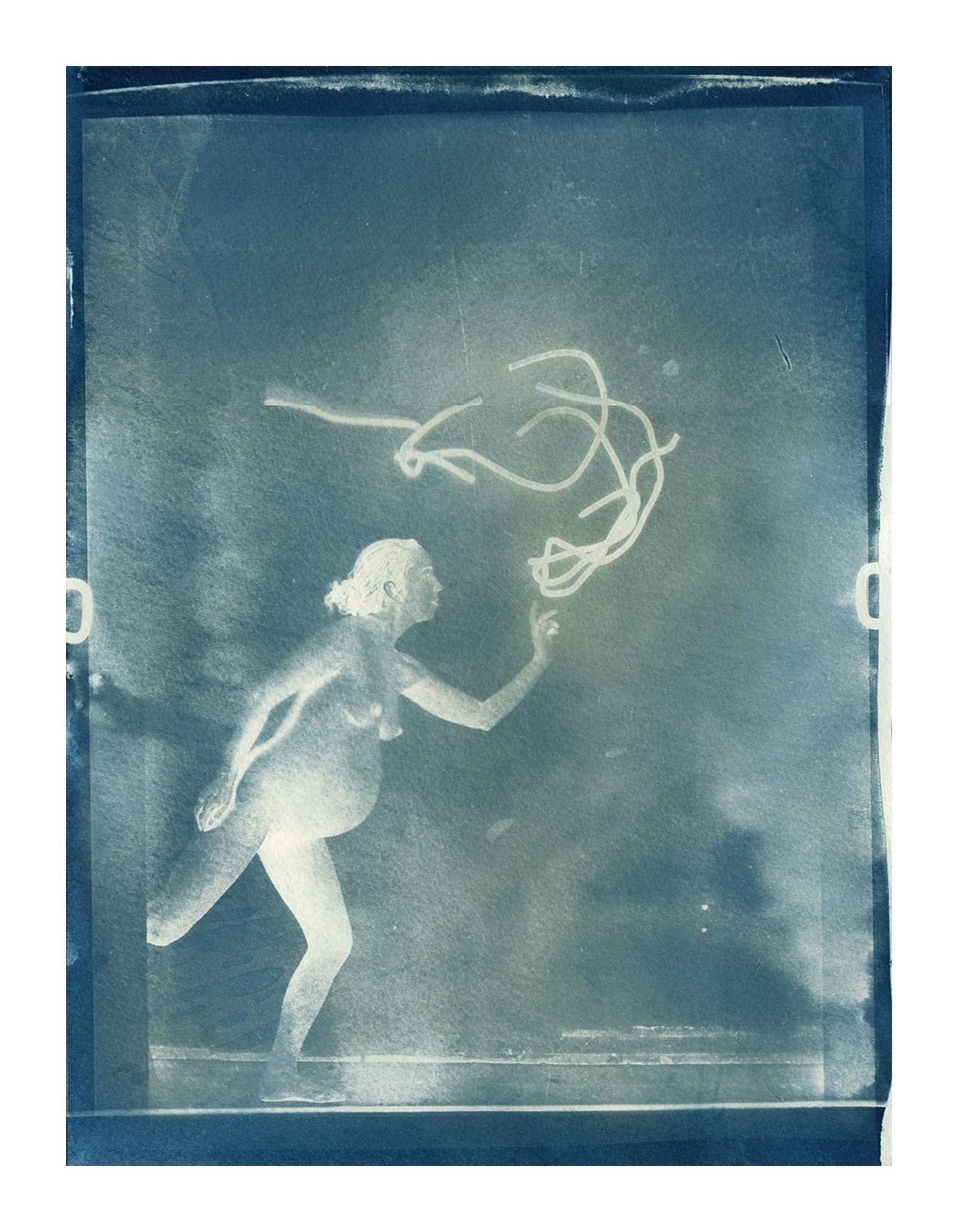

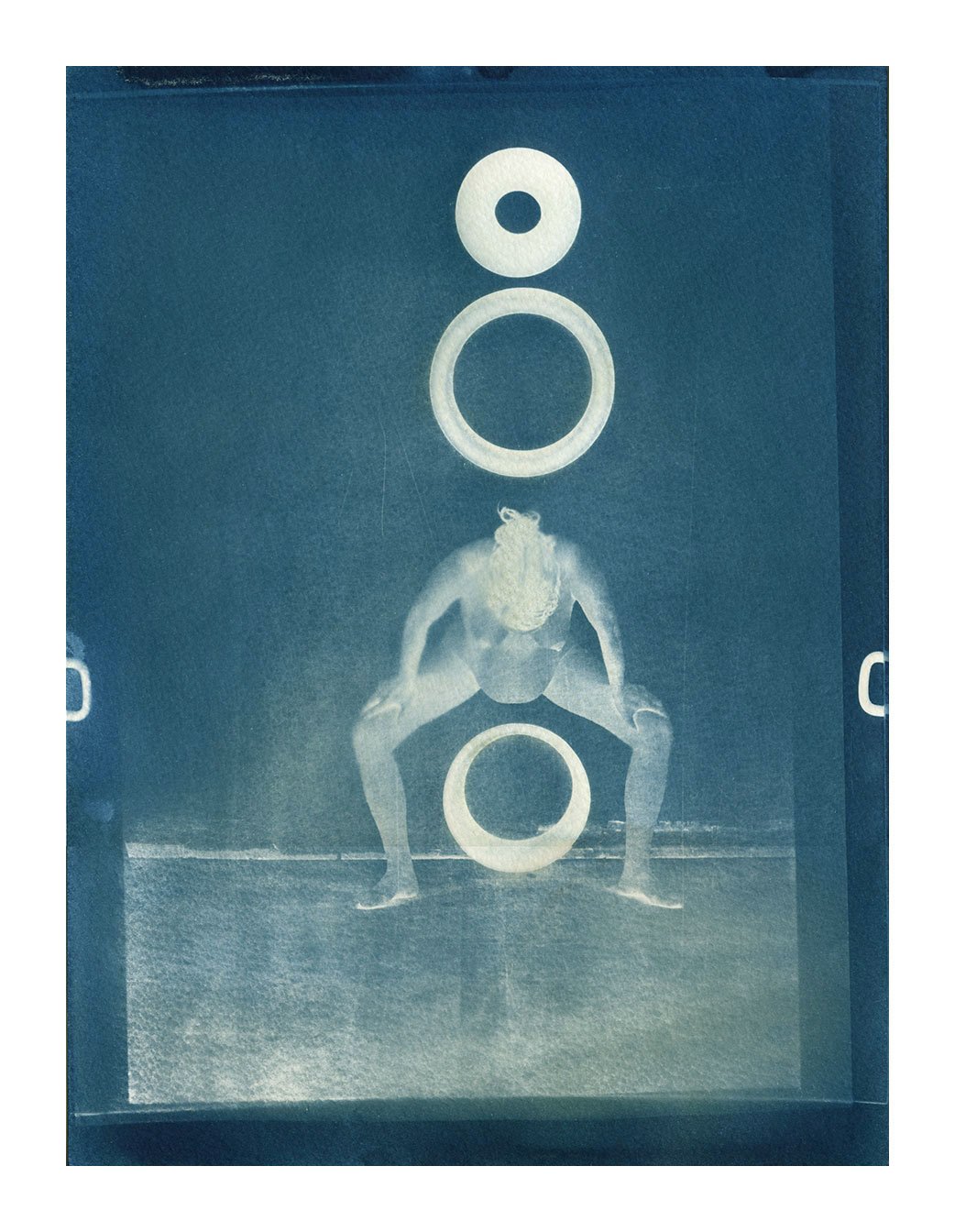

Shanti Grumbine is a multimedia artist whose intimate relationship with materials, along with her broad conceptual investigations, brings her work somewhere between craft and conceptual art. Which is appropriate, given that she’s drawn toward aspects of both. Her work interrupts the value systems that we live by, while questioning the role of art as another commodity in a bloated capitalist system. In one series, Grumbine collects discarded objects that she finds on the side of the road and brings them back to her studio, where she recreates them as scaled-up versions. Like the original object, which is often a mere fragment, her sculptures are unidentifiable, like that section of a broken arm of a pair of sunglasses that wraps around your ear. Grumbine treats these nameless ‘things’ with a sort of reverence, as they point to a value system beyond any conceivable market value, and indeed beyond even their own usefulness. Her work has a devotional aspect, as it brings our attention to the overlooked but sacred world that is simply everywhere, if only we could see it. Grumbine affords us the opportunity not only to see but to engage with those aspects of our culture that are marginalized and invisible. A great compassion emanates from her work quietly and unexpectedly, as she pulls back the curtain and lets us see and experience the sacredness in everything. In the process of translating insignificant objects into a lofty visual language, Grumbine urges us to question our entrenched value systems, and maybe try harder to see the beauty in every little thing.

MH: It’s hard to label your work because you work in many mediums, and you seem to work in series as well. Are you good with not being categorized as this or that type of artist?

SG: It’s something that I struggle with. My tendency is to move through different media and projects as my location or life situation shifts. My hands and mind are digressive and when I get an idea, I have to see it through. It can feel unwieldy at times, and yet the unwieldiness is exciting to me.

MH: Do you ever have issues with being categorized as an artist in general? I’m wondering if you prefer “artisan”, which is sort of ‘artist light’, and has fewer expectations around it.

SG: Ann Hamilton refers to herself as a maker, and I love that term. It has breath and space in it, and it also feels very grounded and humble. It has that sense of going into something that starts as nothing, and then becomes something as you engage with it, whether it’s with your hands or a conceptual process. And there’s the craft element, and something magical too, to make something exist that wasn’t there before.

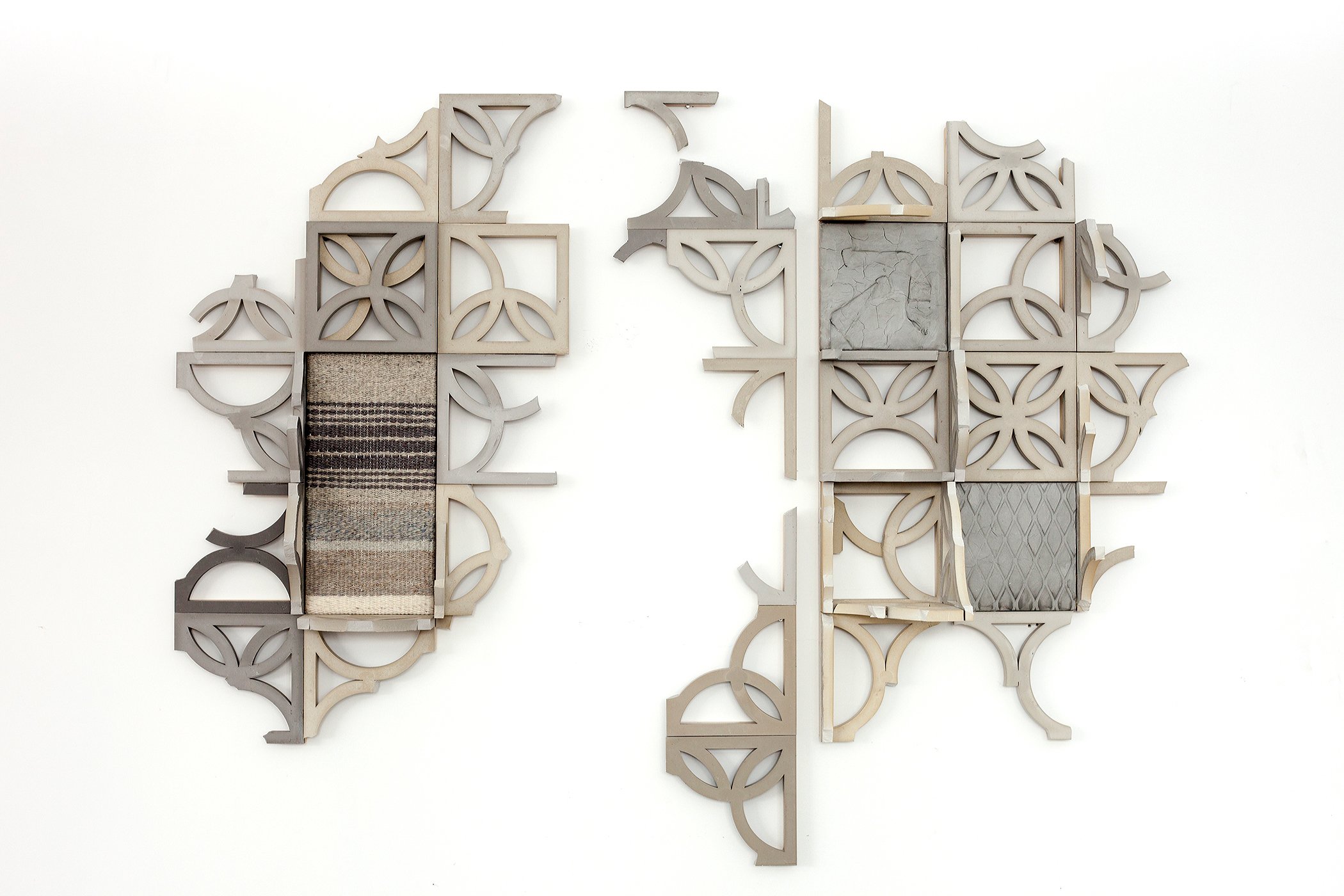

MH: A lot of your materials come from the tradition of craft: weaving, dry felting, form sculpting. What is your relationship to the craft world?

SG: I’m interested in things that are beautiful and well made, and that’s what I attempt to achieve in my work. There’s a kind of generosity and authenticity when something is well made, and that’s meaningful to me. The materials, like wool and thread and felt, are also very grounding, and they’re not bloated with art history. Craft taps into a different kind of history that’s oriented toward function rather than market value. I also think a lot about the Industrial Revolution, when there was a shift in value systems and skill was traded in for profitability.

MH: Not too long ago, craft was officially embraced as “fine art”, which everyone agrees is well deserved, but it also has a cringe aspect. It implies that crafters everywhere were pining to have their work recognized by the art world, because they couldn’t possibly be satisfied by sitting at their loom or potter’s wheel and making things. Do you find the acceptance of craft into the art canon to be presumptuous?

SG: I think what you’re pointing to is a specific value system of the craft tradition and its relationship to the value system of the art world, which is more market-driven. This brings up a core interest of mine, which is an investigation of value systems and how they came about, who maintains them, and what it takes to dismantle them. Maybe by inviting the craft world into the fine art world, we’re starting to embrace alternative value systems.

MH: Do you think that when the art world invited the craft world in, like a big cattle call, the art world had more to gain than the craft world? Like the art world needed something from the craft world to bring it down to earth?

SG: I imagine so. I know that I have. Craft brings with it a respect for the material world, with an acknowledgment of material agency. It decenters us along with our notions of genius and will and that is important. And it acknowledges lineages of making that are not white or male-centric.

MH: Back to your use of mediums. I see you as a materials-oriented artist, and it seems that you love the journey of experimentation. Is the diversity of materials intentional? Does it keep the work fresh, and does it help in avoiding categorization?

SG: It’s interesting that you ask if I’m trying to avoid categorization, when I’m desperately trying to be categorized! (haha) But it’s nice to view it as a strength rather than this thing that I’m always entangled with. I struggle with not being categorizable because it’s not lucrative. It’s harder for people to pin me down, curate me into a show, create a collector base. But I love working with diverse materials and sometimes my work is the material investigation itself. And then there’s this conceptual investigation happening at the same time. I like the parallel investigations, the back and forth between the hand and the mind.

MH: How do you feel about “branding”? The B word. I feel like it’s a gated community for creativity. What’s your take?

SG: I’m never going to be able to do that. Like if someone were to look at my work and say, “That’s a Shanti Grumbine”, that’s a game that I can’t play. I mean I literally don’t know how to do it.

MH: Do you think most artists know how to do it? I think they don’t.

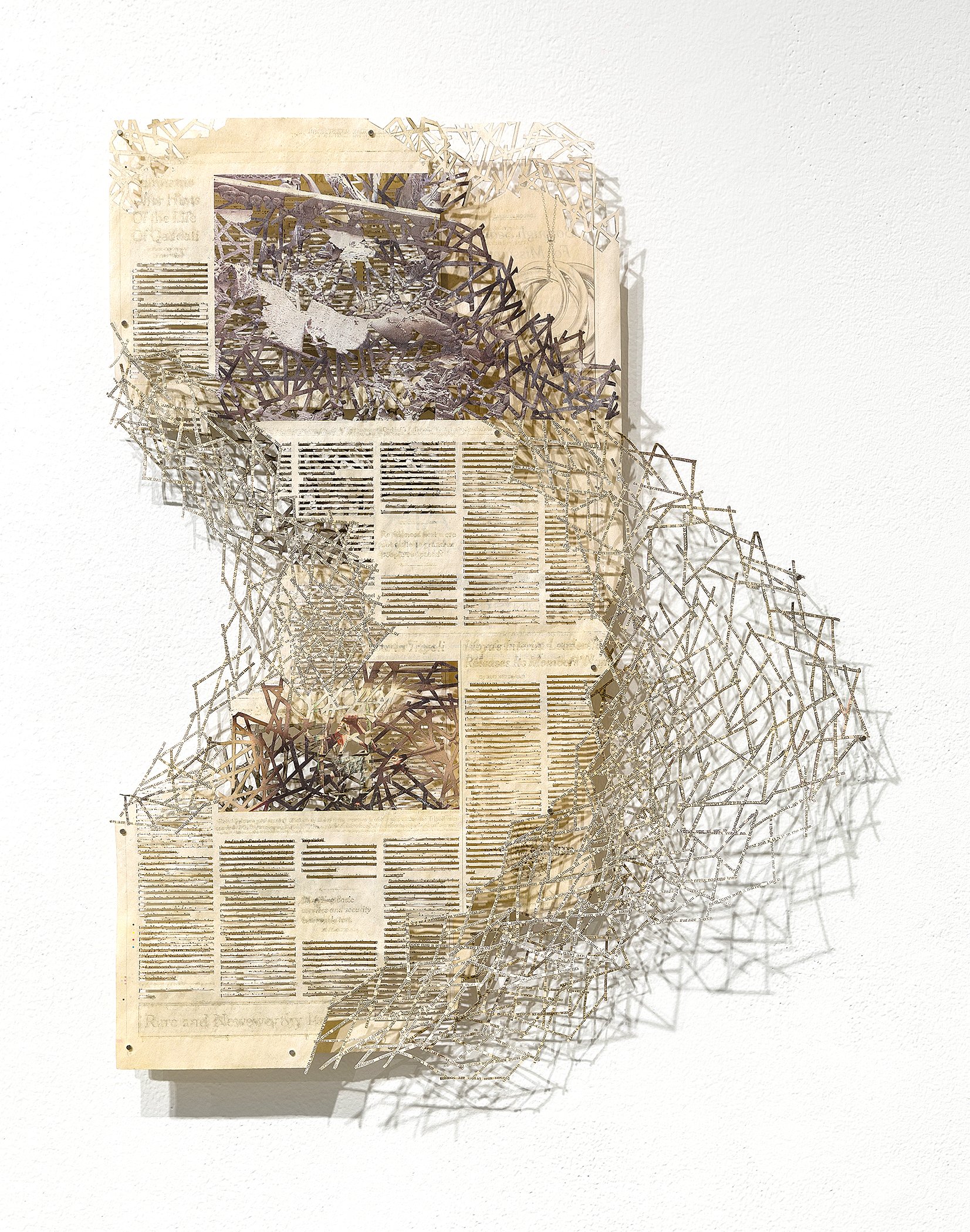

SG: I’ve been asking myself these kinds of questions, partly because I’m a single mom and I need to make money. When I was doing my series with newspapers, there was this moment when suddenly, that’s who I was. I had a brand, and I felt so boxed in! And invisible. It’s like going through life with the tip of your pinky showing and nothing else, and people only know you as the tip of your pinky. I needed to shift gears, and I needed the time to do it, so I did a year-long residency in Roswell, New Mexico. I was looking at other models of art making, and I saw that there are project-based artists that respond to various environments or situations. This was something I wanted to embrace and aspire to. It was a big realization, and a relief in some way.

MH: Isn’t being a project-based artist antithetical to branding? With branding you have a style, and that’s who you are.

SG: Right. Branding requires a different temperament than what I have.

MH: A common thread that weaves through your work is transformation. You find and collect “mundane objects that exist in the margins of our lives” (your words), and in one way or another transform them into something else. What is it about the transformation that appeals to you?

SG: There’s something sacred about paying attention to an object that has been overlooked, and I think that attention is the source of transformation. There are two things that are happening: there’s the visual transformation of the object when I notice it, then there’s the transformation that happens in my interaction with the material as I make it. But then I’m also transformed by the engagement. The process allows me to see the world around me and engage with it differently.

MH: So you’re out for a walk, you spot a nondescript object on the side of the road, something about it draws your interest so you bring it back to your studio, and then create a scaled-up version of the object. What have I left out of the process? What are some other considerations?

SG: That was a specific project that I started when I was in Roswell. I was dealing with pain from chronic Lyme, so I had to walk to alleviate the pain, and it became part of my studio practice. Walking along this specific route became my daily pilgrimage, and I started paying attention to what was along the side of the road. I started collecting these objects that had been transformed by exposure and use. They were no longer categorizable because they had left their old value system and entered into a new realm that felt full of possibility. I experienced these objects as relics and began to read about the history of walking and pilgrimage. I witnessed the pilgrimage that happens once a year to El Santuario de Chimayo, in Northern New Mexico. The destination chapel holds a well of blessed dirt, a base element made holy through attention and devotion. I also thought about reliquaries and pilgrimage sites I experienced as a child on a family trip to Europe when my mother was teaching about the Crusades. And I thought about the bones of saints housed within cathedral altars. We choose who and what is sacred.

MH: You told me that you don’t know what the found object is; you don’t want to know. Why not? Would knowing its purpose and history affect your process?

SG: Sometimes I know, like one of my sculptures, Column, is modeled after a worn piece of a pair of sunglasses. I like knowing and not knowing what it is; it exists on this precipice between the sunglasses and this other magical, bone-like existence. It’s a liminal space between what it was and what it’s becoming. There are other artists who have enlarged the things that clutter our lives, like Claes Oldenburg, who enlarged these fetishized objects in our culture. I find objects after they’ve shifted into this other state; I’ve found them in their thingness. They’re no longer what they were. It’s a different approach, a different investigation.

MH: What do you mean by thingness?

SG: Bill Brown writes about the concept of “Thing Theory”, which says that an object becomes a thing when it can no longer serve its common function. An object disappears into its use value: I pick up a glass, I drink, I don’t think about the glass. But if that same glass breaks, there’s a stutter in that experience, and it becomes a thing. So thing theory is about the ways in which the things in our lives affect and transform us. Bill Brown also talks about our bodies as objects and the way that physical injury disrupts our performance, our objectness. This theory resonates with me on a deep level due to the way chronic illness interrupted the functionality of my own body, shifting my sense of self. Illness turned me into a "thing among things".

MH: I find it interesting that when reproducing the thing, you’re not making it different than what it is. You enlarge it and in doing so you magnify its ordinariness. What is it that you would like us to see? What do you see?

SG: When I have this moment of visceral connection with a thing that has no value, it interrupts the value systems that I live by, that I’m burdened by. My engagement with the thing gives me the agency to interrupt the capitalist, market-driven value system with something that has a very different type of value. I don't think I enlarge it to magnify its ordinariness, I magnify the ways it feels extraordinary to me. And I enlarge it to occupy the physical scale of my body.

MH: I see in your work a Zen-like quality that places value on the ordinary and unadorned. The sacred isn’t something to be sought after like a shiny talisman, but in whatever presents itself in your daily, repetitive routine. Is this something you think about in your studio and in life?

SG: Since I’ve been chronically sick for ten years, there’s been a narrowness in my experience. Art has been the doorway that lets me learn anything and everything from whatever happens to be nearby.

MH: Is the sacred aspect of the piece inherent in the object itself? Or does your process of transformation make it sacred? You talked about translation during my studio visit, and it’s interesting to think about how a nameless object becomes sacred as you translate it into another visual language.

SG: What I’m really interested in is how we encounter the objects in our world, and how we encounter each other. We choose our value system, and we choose through our attention what is sacred. By transforming these nameless things into devotional objects, I’m exercising my choice by giving it my attention, which challenges market-driven value systems.

MH: All spiritual teachers will tell you that everything is sacred. The object that you pick up on the side of the road is just as sacred as the object that you didn’t pick up, so the reason you choose one over the other is more a matter of aesthetics.

SG: Yes, and I’m curious about that. What is desire? Why am I drawn to this and not that? I experimented with that in my earlier work, when I was looking at these luxury items in the newspaper and extracting them from their context to understand what is desirable and why. I was investigating how our desires have been formed by advertising, and why we’re drawn to certain shapes.

MH: Maybe translating the unremarkable object into a different visual language makes it desirable, not sacred. Because in theory, it’s already sacred.

SG: Yes. I’m also curious about what makes a shape desirable. The object on the side of the road had a specificity to it, but I couldn’t place it. There would be a lighter, and it had been out so long that the plastic had transformed into something almost marble-like, where the surface has this gorgeous feel to it. I thought that if I were to recreate it, I’d be touching into what it’s pointing to, that liminal space that I’m so drawn to.

MH: So it’s not just the object you’re interested in, but what’s happened to the object.

SG: What it’s pointing toward. Each object was different but had a suggestive power to it.

MH: That’s interesting. I can understand that the object has a history, but you’re saying that it also has a future?

SG: Yes! You buy a souvenir that points back to a nostalgic point in time, right? But these objects are like souvenirs that point forward to some possibility of value.

MH: Souvenirs of the future! How do you suppose they’ll have value in the future? To me they’re spent; I think of them as dead. What value could they have?

SG: They point toward a different value system than the one they’d previously been engaged in.

MH: How important is viewer engagement? Could you say that the viewer transforms the object into something sacred just by seeing it? I’m wondering at what point a mundane object becomes something extraordinary. Does it happen the moment that you pick it up from the ground? Or is recognition required from an audience?

SG: The viewer doesn’t have to see it as sacred. But the attention and generosity of showing them both the object and the enlarged version allows them into the process, and I think it’s palpable, if I’ve been successful. For me, engagement is important because it slows me down. Our culture is very fast, we take things in very quickly, and we’re not always aware of what our reactions are. When I was cutting newspapers, the engagement slowed me down. Cutting into the newspaper, removing the words, I became aware of its structure and the engagement and translation slowed me down.

MH: You also talk about the value of repetition. Could you elaborate on that?

SG: I’m always thinking about repetition. It came up in a recent project called “Laps(e)”, which is a video piece, a weaving, and a text. The video is of me swimming laps, and I’m wearing a GoPro, so you see what I see as I’m swimming. The back and forth of my laps parallels the back and forth of the weaving and the back and forth of writing. I’m interested in this type of repetition that Gertrude Stein refers to as insistence. She writes that when human beings do something over and over, it’s a type of insistence. As a single mom I’m constantly doing repetitive things, but if I think of it as an insistence, it feels celebratory and strengthening. And when I think of mass-produced objects turning into a singular state through repetitive use, that’s a kind of insistence as well.

MH: What do you mean by insistence? How is weaving a kind of insistence?

SG: When you do something over and over, it’s not just a mindless repetition, but there’s a shift in emphasis. Regardless of intention or will, there is growth or strengthening. Like weaving isn’t just repetition, it grows. The skill accrues, the collaboration with the material shifts. And swimming laps, the muscles start to develop. Something is being transformed.

MH: It sounds like insistence is like repetition with a will. Or with an agenda.

SG: I don’t think there’s even an agenda. Something grows, something is transformed, something shifts. Even if there’s no agency, there’s a rhythm. Even if I have no goal, transformation and shift happens.

MH: Is insistence built into the whole human experience?

SG: Yes, I think so. But repetition is necessary for any type of value to accrue. I think that’s why rituals are important, and mantras, and why politics and advertising are successful, and why we have to be careful.

MH: I was recently asked by a non-artist why making art was important to me. I had a hard time explaining! How would you respond to the question?

SG: It’s important to me because it gives me access to an alternative value system that makes me slow down and pay attention, rather than allowing everything in my life to disappear into usefulness. The studio provides an opportunity to engage with my hands in a way that I don’t have anywhere else. It feels like a sacred practice, like going to synagogue or temple or church. It's a sacred space.

www.shantigrumbine.com

Shanti Grumbine’s solo show "In Formation", curated by Matthew Lopez Jensen, is up through March 1.

575 Madison, NYC Open 24/7