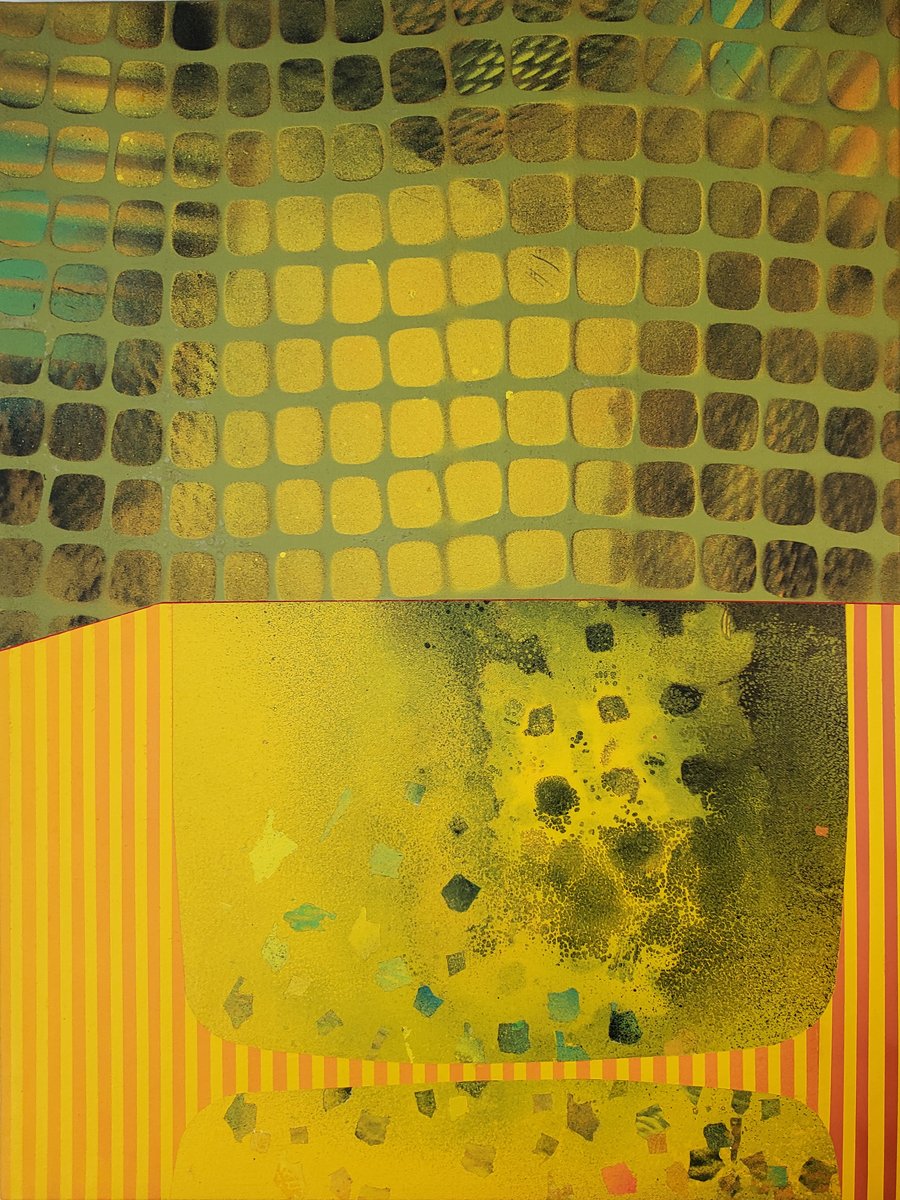

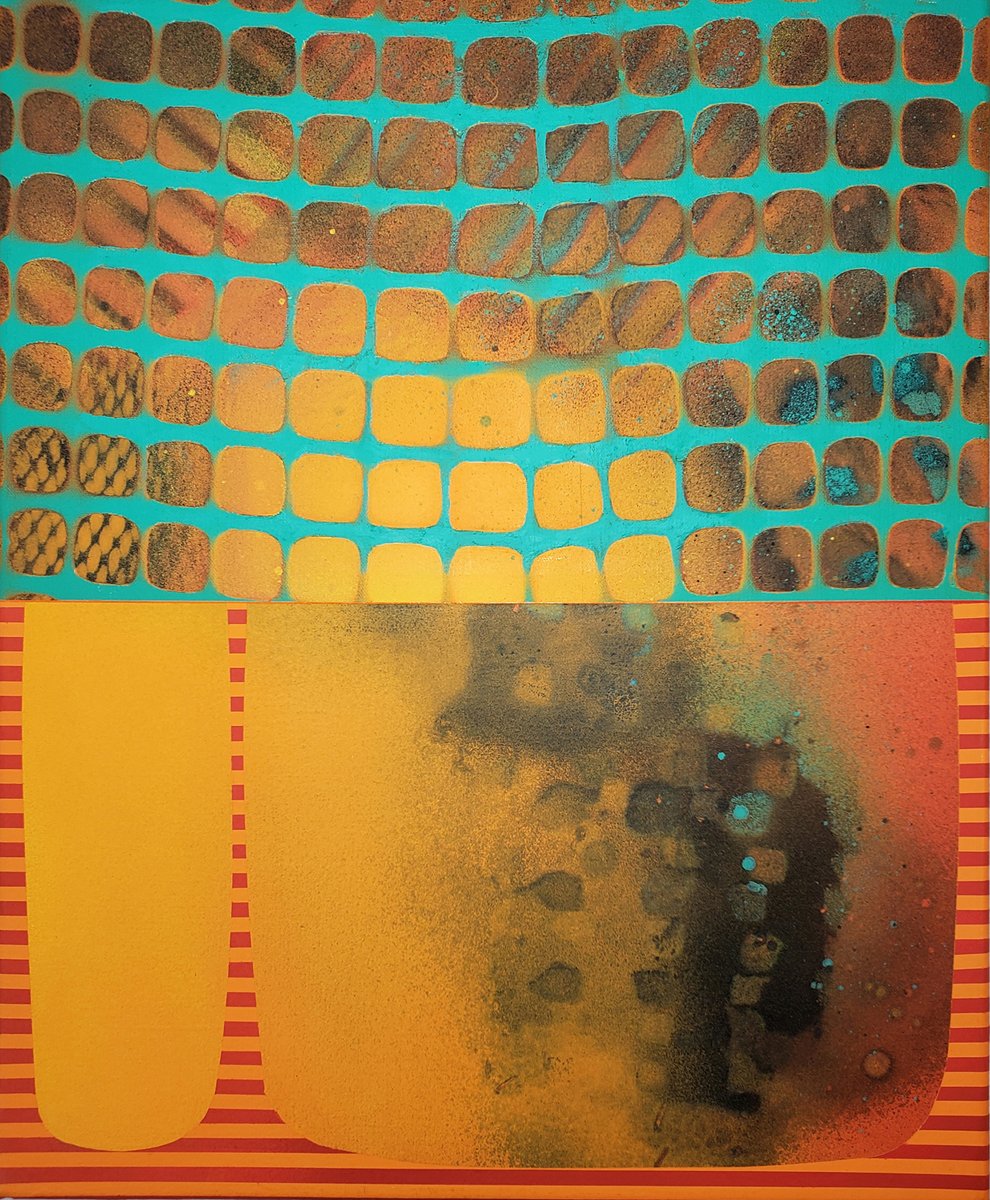

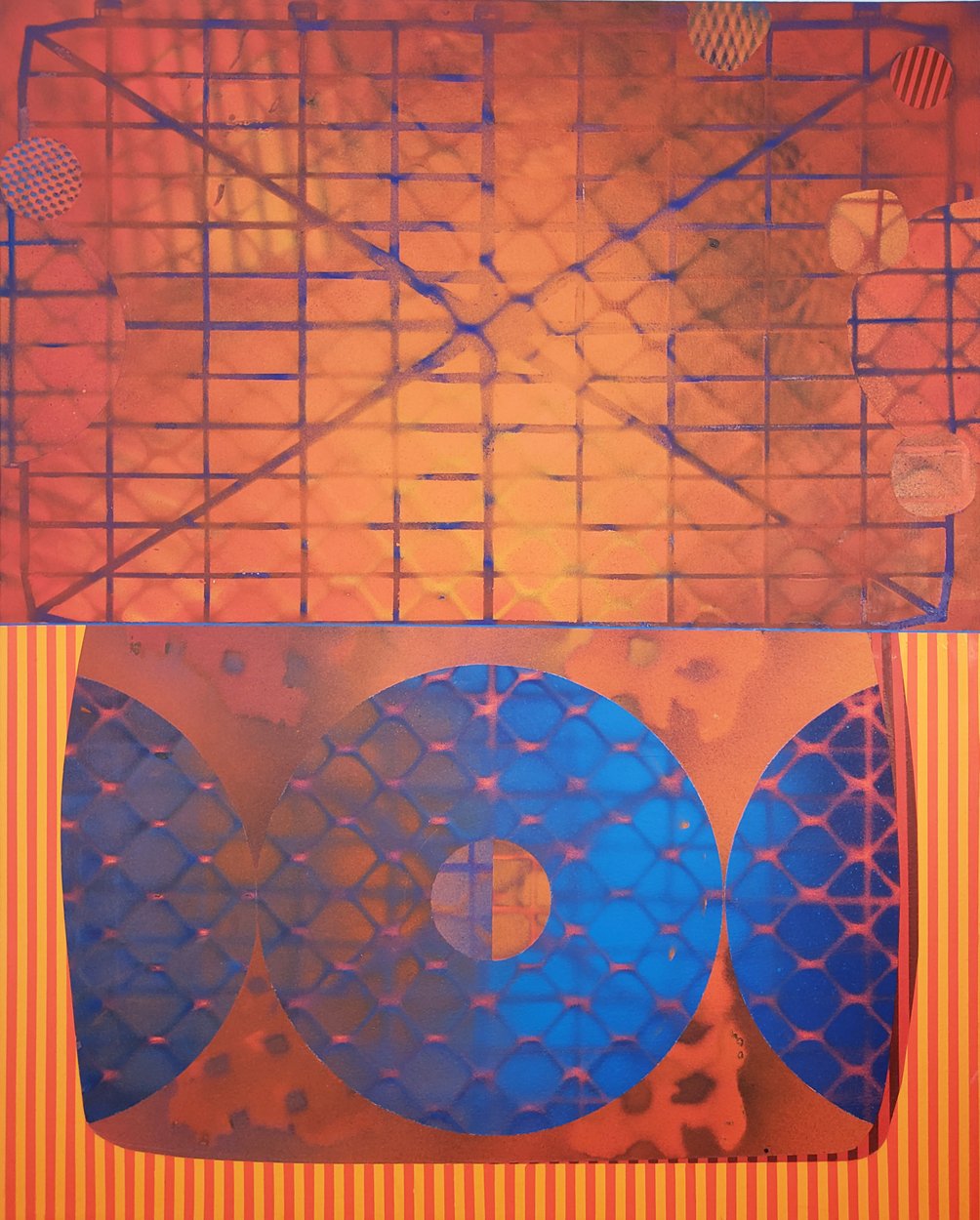

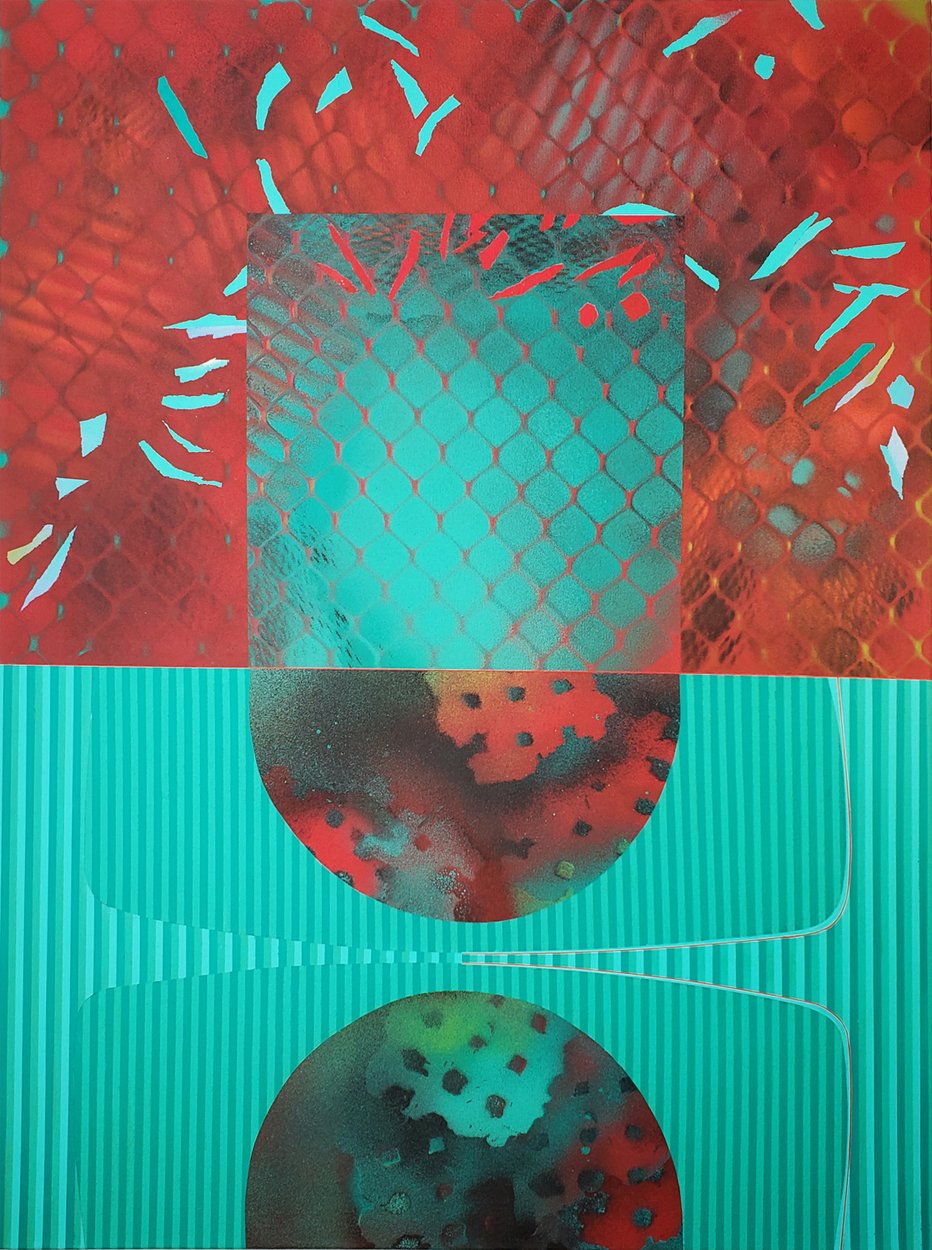

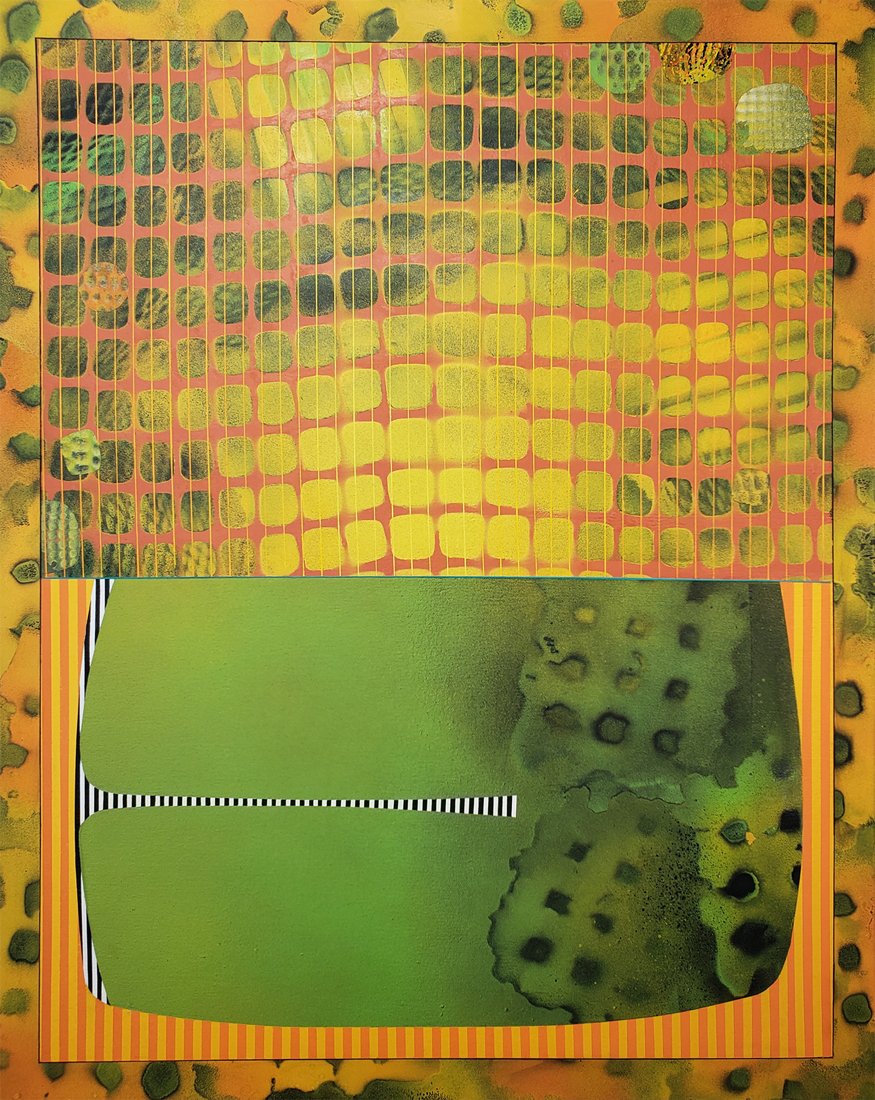

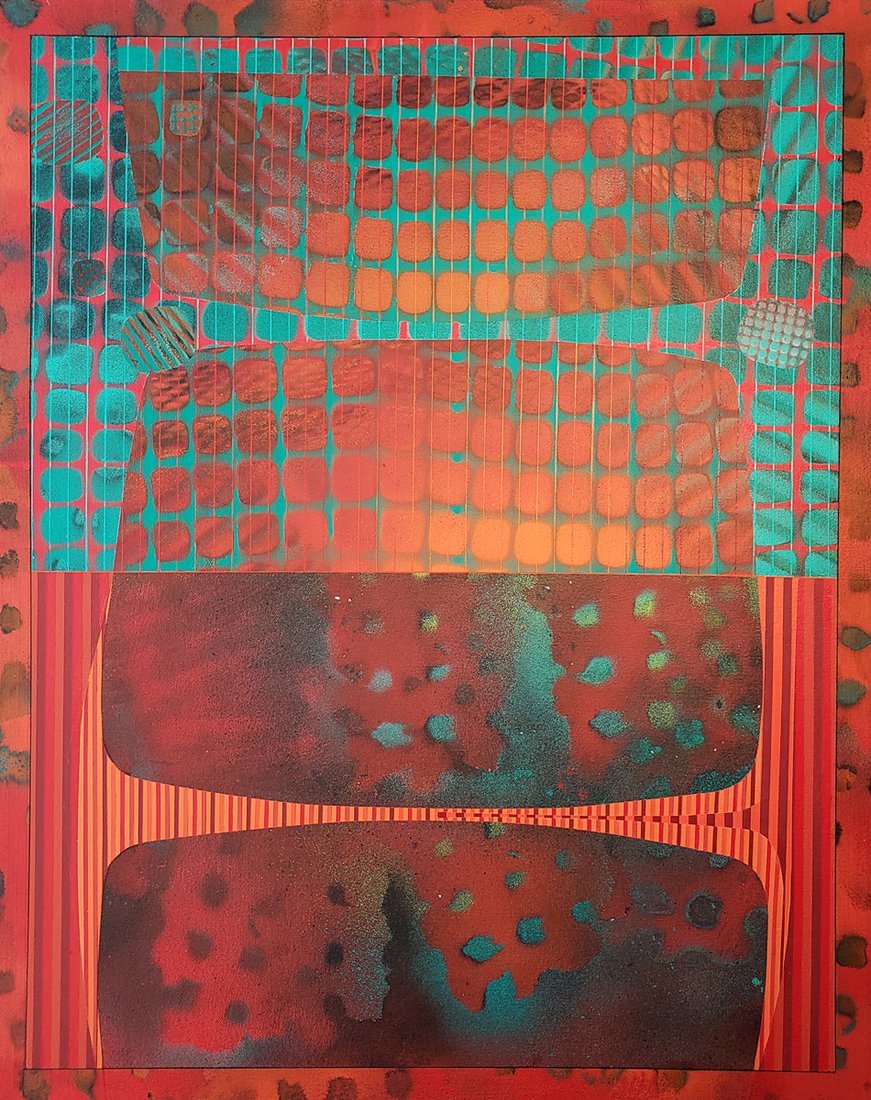

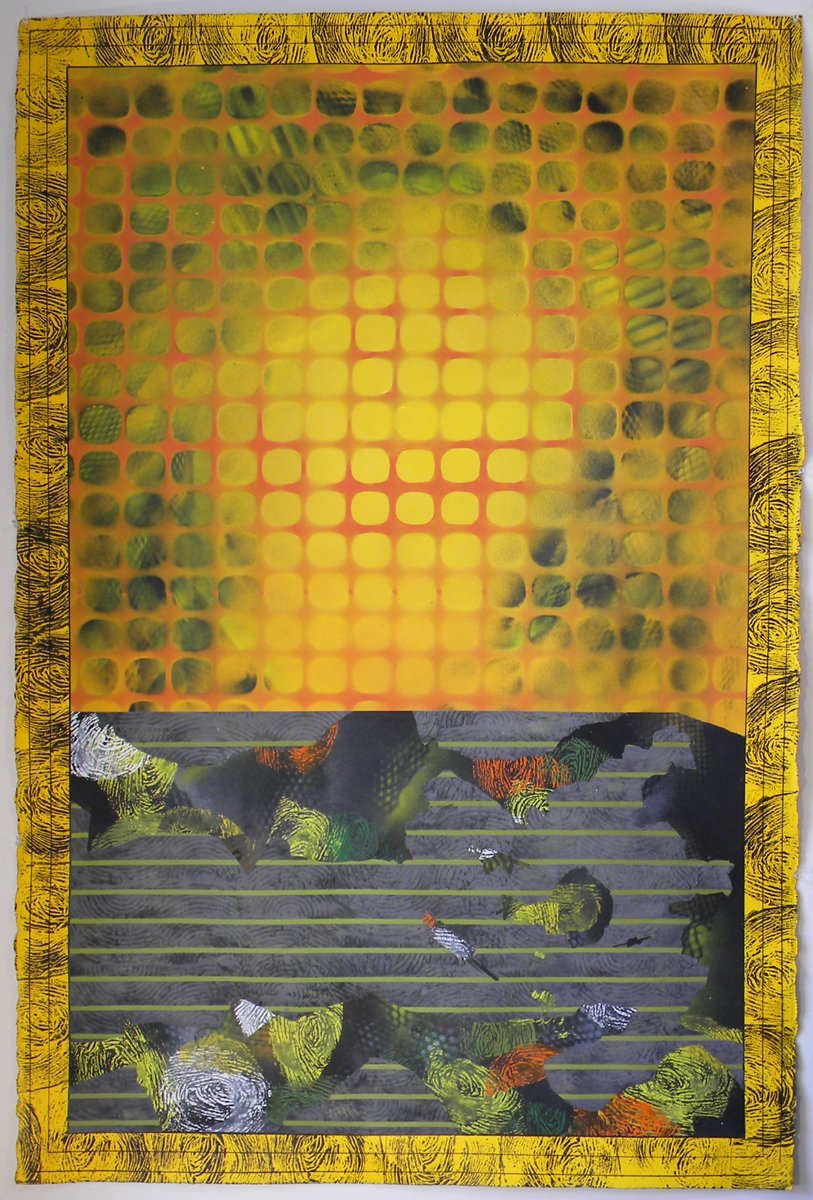

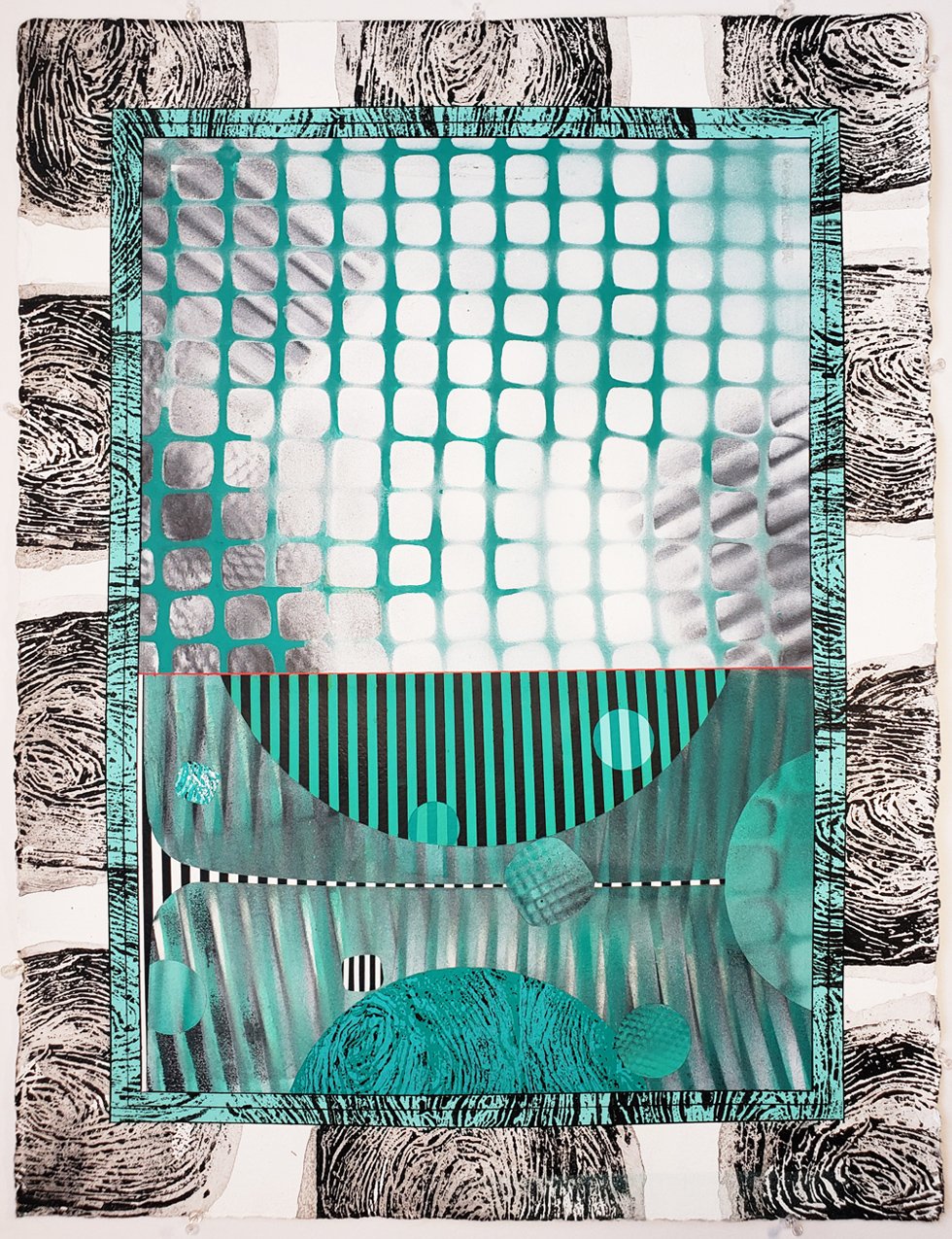

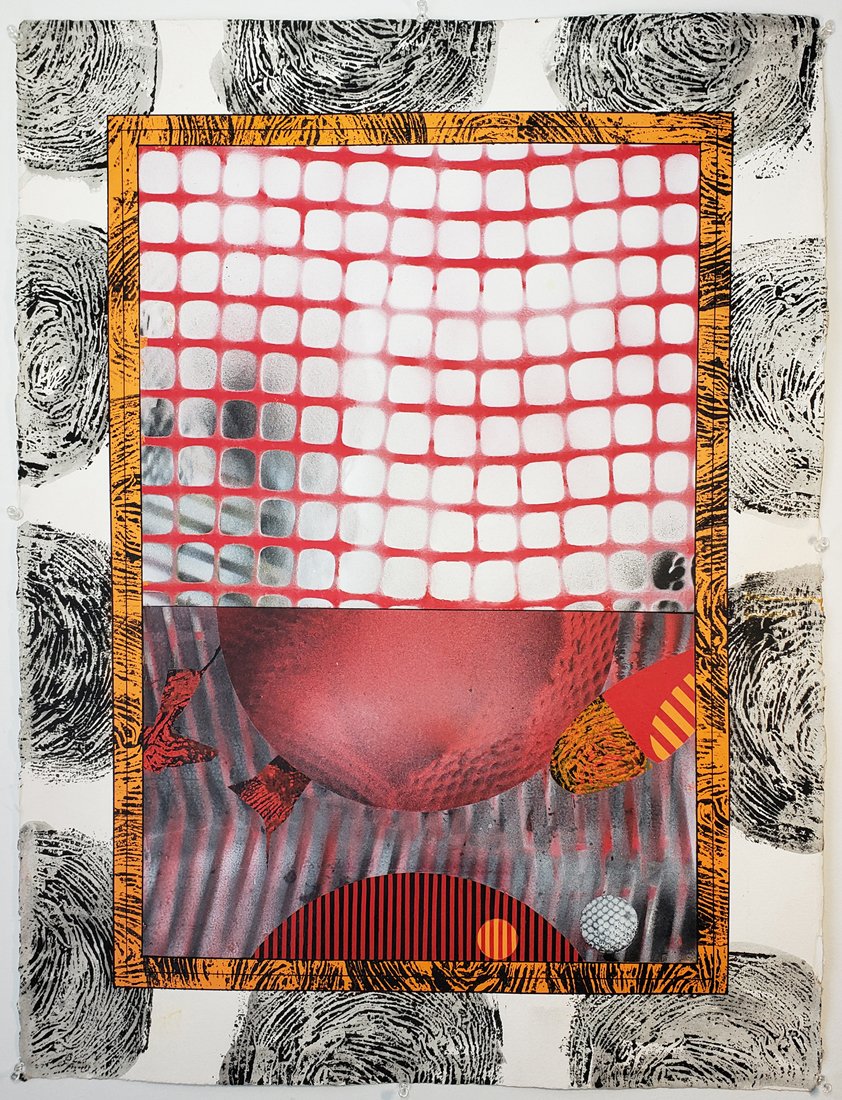

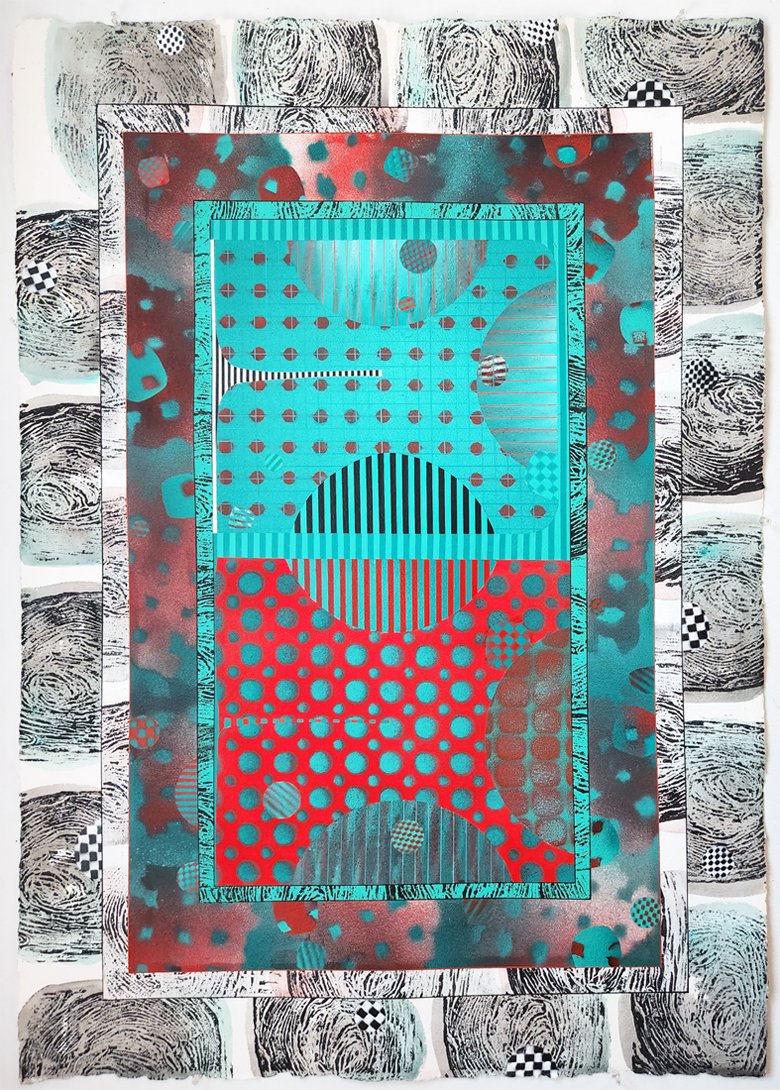

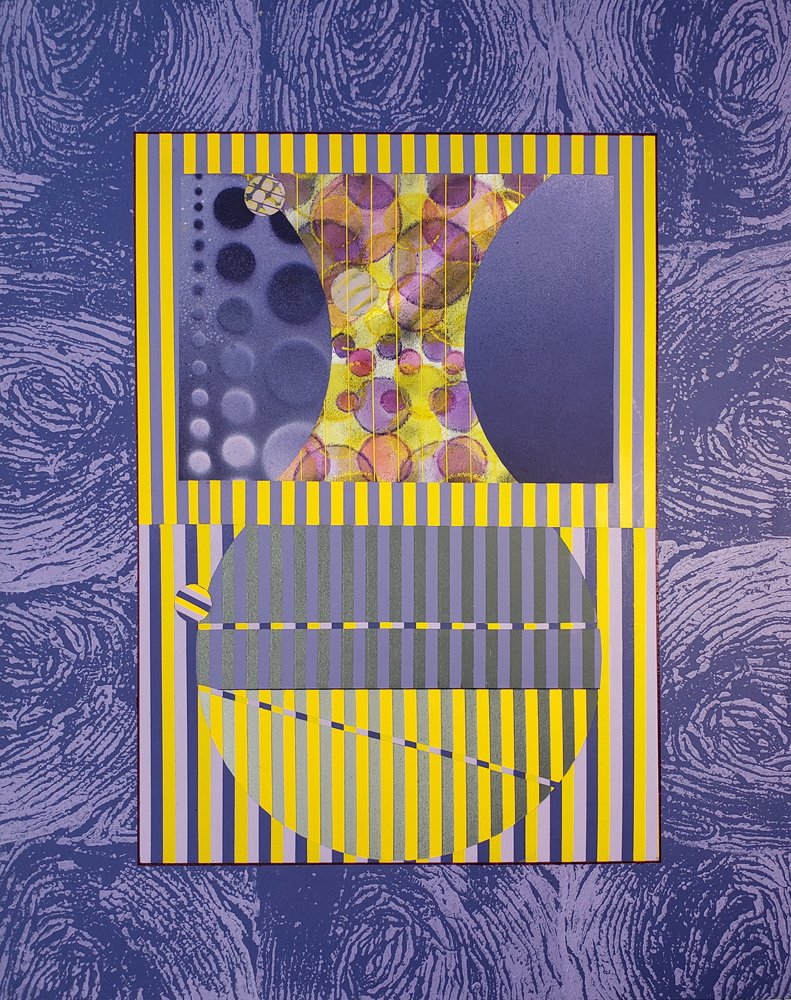

Jane Sangerman explores the pictorial space of her paintings by creating a seductive portal that draws us in, only to encounter barriers that deny access. Far from pushing us away, these obstacles deepen the mystery, heightening our desire to circumvent them and enter the enigmatic space that lies beyond. The barriers most often appear in the form of the plastic fencing that is ubiquitous in Bushwick, where Sangerman lives and works. In her paintings and works on paper, Sangerman builds up thin layers of color through her medium of spray paint. The canvas is divided into top and bottom sections which she works independently of each other. She describes the upper half as the metaphysical realm, a space full of secrets and infinite potential. The lower half is the material world, but far from mundane, it inspires the saturated colors and metaphors that energize her work. Sangerman connects the two by creating patches of color and texture from the buildup of spray paint. These patches float in the foreground, as if waiting with us to pass through the plastic fencing and be ushered into the great beyond. Sangerman is fascinated by urban decay, an avid collector of rusted metal that she finds on the streets or pulls out of dumpsters. Using the metal as a mesh to spray through, she creates shadowy layers of grids that hover in the lower section. She regards them as urban artifacts, embodying the energy of those who have previously handled them. This is humanity encased in materiality, no less profound than the mystical space that dominates the upper half. Indeed, Sangerman’s paintings reside at the intersection of the upper and lower realms, an amalgamation of the magical and the ordinary.

MH: Tell me about your studio practice. I was surprised to hear that you use spray paint, and that you rarely paint with a brush. How did you discover this medium, and what about it is appealing to you?

JS: The physicality of the materials has always been an important part of my process. Prior to spray painting, I was building up layers of found objects that I’d attach to a painting. Somehow I ended up with a pegboard, and I was attracted to the tiny holes so I decided to spray paint through it, and I liked the effect. I built up layers of spray paint, taping out areas and blending colors so they’d dry together in a seamless, matte finish.

MH: Do you think living in Bushwick has influenced your choice of materials?

JS: My palette is much more intense from the constant exposure to the murals and graffiti. I was shocked when I first moved here! Bushwick is the spray paint capital of the world, and there’s not a square inch that isn’t visually active and colorful. There are murals everywhere, and there’s a store close by that sells spray paint and nothing else. But I was already using spray paint when I lived on the Upper West Side.

MH: Were doing the same work that you’re doing now?

JS: Yes, but without the fencing and barriers. We moved here at end of 2018, and I welcomed the change.

MH: You mentioned that you started out in lithography, and that this continues to influence your work. How so? What do lithography and spray paint have in common?

JS: I come out of a printmaking background, where the colors are separated into different runs. This is similar to how I work with the spray paint, because I’m always thinking about the layer beneath, and what parts of the image I want to grab as I progress through the painting. This requires taping off sections, which is an important part of my process. So whatever stage of the process I’m in, there’s always evidence of where I began.

MH: That’s interesting. So there’s always something from the bottom layer?

JS: Yes, and that comes directly out of lithography, where you mask out with gum Arabic and try to get the ink films to dry together into a unified surface. This is essentially what I’m achieving with the spray paint.

MH: You describe your work as having many layers. I take that to mean layers of paint as well as levels of meaning. Why do you build up these many layers of paint, often concealing the painting beneath?

JS: It’s the way that I need to work to achieve the effect that I want. In the lower half of my paintings I have some flatter areas with striping, which requires a lot of underpainting. If I can’t get what I’m looking for, I may need to do the whole thing over again, which requires taping out, masking, and spraying a solid area. But the good news is that I can do it again, and I can keep doing it, and the fun part of working in this way is a collage effect. So in the process of trying to achieve what I want, this interesting effect happens.

MH: I find it interesting that you enjoy the process of taping off areas of the painting, a necessary step before spray painting. And you do it in the wee hours of the night, while listening to garage bands on your headphones. I love that image! Is this the meditative part of your practice, where you lose yourself and deeply connect with your process?

JS: Absolutely. I enjoy the process of trying to tape a perfect circle. It’s very satisfying and meditative, and I do this in the middle of the night. I also like to sit in my chair and sketch out ideas. It’s another thing that I tend to do late at night when there are no distractions.

MH: Your canvases are consistently divided in half by a horizontal line, delineating the top and bottom sections of the painting. This creates an interesting dynamic, almost a hierarchy in pictorial space. Is there intentionality behind this division?

JS: There is. It’s a universal above and below idea, and it’s become increasingly important in my process. It’s not enough to create a metaphysical space; I also need a flat space, our physical world, where my environment informs me. It’s the junction of the two spaces that charges me up.

MH: I remember being taught never to divide the canvas in half.

JS: Yes, it goes against everything I learned in art school, which said that you should work the whole piece at the same time. I think of it as spliced film. I’m always trying to cut things in half, and then connect them. I begin in the top section because it’s the place where I go to lose myself. And the bottom is just as fulfilling because I’m responding to my immediate environment, which is Bushwick.

MH: Are you exploring two different sides of yourself?

JS: Possibly! I find myself an enigma, like most people do. I can’t help but pull in my world, but at the same time I want to go somewhere else. I can’t come to an agreement without showing both of those.

MH: I see you as a cerebral person because you’re a reader and a thinker, but you’re also in your body as an athlete. So the top and bottom halves of the painting express the totality of who you are as an artist and a person.

JS: That’s interesting. I’ve never fit into one group very neatly. I need both.

MH: I’d like to dig deeper into the top and bottom sections because I’m intrigued by their juxtaposition. You describe the top half of the painting as a mysterious space that’s infinite, and where you go to get lost. In your words: “It’s the sort of space where I feel like I could discover the secret of something.” Would you elaborate on that?

JS: I like to think that I’m going to discover something in the top half. This is the unknown, a space full of timeless secrets. There’s so much in our universe that we don’t know, and this is where I go to search and play. What’s in there, and what’s out here? It’s all connected, and I love to think about that as I paint.

MH: Interestingly, this space is also where your fencing shows up. It’s like you’ve discovered a passage into the infinite, then created a psychological barrier that has to be negotiated. How do you think about the fencing in your paintings?

JS: It was a spontaneous idea. I’m a runner, and as I’m running around the neighborhoods of Bushwick I pass all these construction sites with plastic fencing that’s permeable, but they create an obstacle. There’s a beauty in looking through this meshy world, and it makes it more mysterious to have something in the way. I noticed that barriers make me want to enter the space, because subconsciously I’m being held back.

MH: Interesting. If the fencing wasn’t there, it wouldn’t have the same pull. By simultaneously pulling you in and pushing you away, it deepens the mystery.

JS: That’s right. This happened after moving to Bushwick. I realized that the upper half of my paintings needed a permeable barrier that would both pull you in but keep you out.

MH: There’s also the idea that a barrier or wall creates value. Right? Because erecting a wall gives the thing behind it more value.

JS: Yes, that’s human nature. We want what we can’t have. And I’m always searching for interesting barriers. I search the internet, but my favorite things are those that I find on the streets of Bushwick.

MH: I can’t help but think of the confessional screen that separates the Catholic from the priest. Your paintings have a similar quality that beckons the viewer into its depths, but to fully enter it, they have to leave something behind. Not necessarily their sins, but maybe their ego and its attachments. Do you assign any religious or spiritual meaning to your work?

JS: I’m from a mixed background. My dad was Jewish, but he converted to Presbyterian, and my mother was Presbyterian. She worked for the church, and I spent a lot of time there, waiting for her. So I was surrounded by spirituality, but I’d be just as happy sitting in a temple or mosque or any reverential place; it would do the same thing.

MH: Is that what you’re trying to create in the top half of your piece, sort of a reverential, expansive feeling?

JS: Yes. A place to go. Churches are special for me because that’s my history, but it’s more about the feeling. The mystery. I have beautiful memories of being in the church, waiting for my mother. I think of it as a place where we’re all connected.

MH: Then there’s the bottom section of your canvas. You said that you think of this space as the day-to-day world in which you orient yourself, and where you come up against something. What do you mean by this? Are you referring to your urban environment?

JS: It’s important to me that I put parts of my physical world into the work. I used to attach objects onto the canvas, but now I’m spraying through objects, things that I find in Bushwick. I love urban detritus and would love nothing more than to be let loose in a scrap metal yard. It would be a treasure hunt for me! All of this ends up in the lower half of the work. The challenge of trying to connect the two worlds is very exciting for me.

MH: So the top and bottom meet at the center of your painting, the metaphysical brushing up against the mundane. It seems that they coexist happily enough, like an old married couple who have learned how to tolerate the other’s quirks. But then there’s a third layer that appears randomly across both spaces. What do these striped patches represent?

JS: The top and bottom need to talk to each other, and these patches serve as connectors. There needs to be some action in the painting – contrast, interaction of color, stripes – that is jarring and affects our eyes in a physical way. The patches create movement in a static area, and they keep your eye moving around the canvas. So they’re a formal device, and the stripes create the effect of a window, something to look through.

MH: You say that you’re drawn to the urban landscape, like the odd shapes that fall from walls and weathered surfaces, and the odd marks that you find in subway stations. Why are you so fascinated with urban decay, and how does this show up in your work?

JS: I think urban detritus is incredibly beautiful. It might make someone else’s skin crawl, but I’ve always been inspired by weather-beaten, worn objects. It takes some magical thinking, but these objects and the urban landscape speak to our humanity. They carry the stories about all the people who have lived there. I grew up in a clean, suburban setting, and I always found the city much more interesting. So the magical thinking is going on in both the top and bottom halves.

MH: What’s the magical thinking in regard to the bottom half?

JS: There’s history embodied in these shapes: where the item was made, the people who used it and touched it, and then all the lives that brushed up against this object.

MH: It’s a different kind of magic, one that we can comprehend, rather than the mystical idea of God or spirit. The idea of unknown men and women touching these objects creates a beautiful connection.

JS: Yes, and then there are all the invisible processes, like the tree that had to grow so that a woodworker could make a chair. I don’t think of this as I’m working, but it’s in my work.

MH: What about your fascination with walls and barriers? Where did that come from?

JS: That came a little later, when I first looked at the work of Antoni Tàpies and his wall paintings. I also looked at Sean Scully, and the walls in Ireland with the tension of heavy stones. So I started thinking about walls, what’s on either side of them, and the beautiful marks on their surfaces.

MH: It's interesting that your medium is spray paint, you have a fascination with walls, and you live in Bushwick. Its seems like a given that you’d be a graffiti artist! Have you ever done that?

JS: No, I’m such a chicken. I have friends who invite me to go tagging with them, but it’s something that I’ve never had the urge to do. I enjoy other artists writing on the walls.

MH: Can you say a few things about the fingerprints?

JS: When I started my art career I did a lot of self-portraits, either drawings or paintings. I wanted to include something of myself in my current work, so I decided to stamp my fingerprints into the painting. They’re cut linoleum prints of my enlarged fingerprints, and they can be read in different ways. I like having them in the piece, and it’s natural for me because it goes back to my printmaking roots. In one series on paper, they create the border, like a baroque frame.

MH: You’ve talked about running through Bushwick, seeing the light pierce through plastic fencing and getting totally inspired with new ideas for your paintings. This sounds utterly sublime, and I wonder if Bushwick has become your muse?

JS: I’ve definitely fallen in love with Bushwick. I love the light, the cultural diversity, the energy, the colors, I even love the sound. It’s very noisy! So yes, I love Bushwick. I only wish there were more dumpsters to climb into and find interesting stuff for my work.

MH: What’s the best part about being an artist?

JS: It’s so hopeful. I feel so fortunate to have something to wake up for, and I can’t wait to start, to put down a new idea and see what it looks like. Or the moment when I peel the tape off and see what’s under there, and how the colors have blended together. It’s never-ending and it can be terrible or good, but I have to do it. It can be hard to be an artist, but I feel very fortunate.