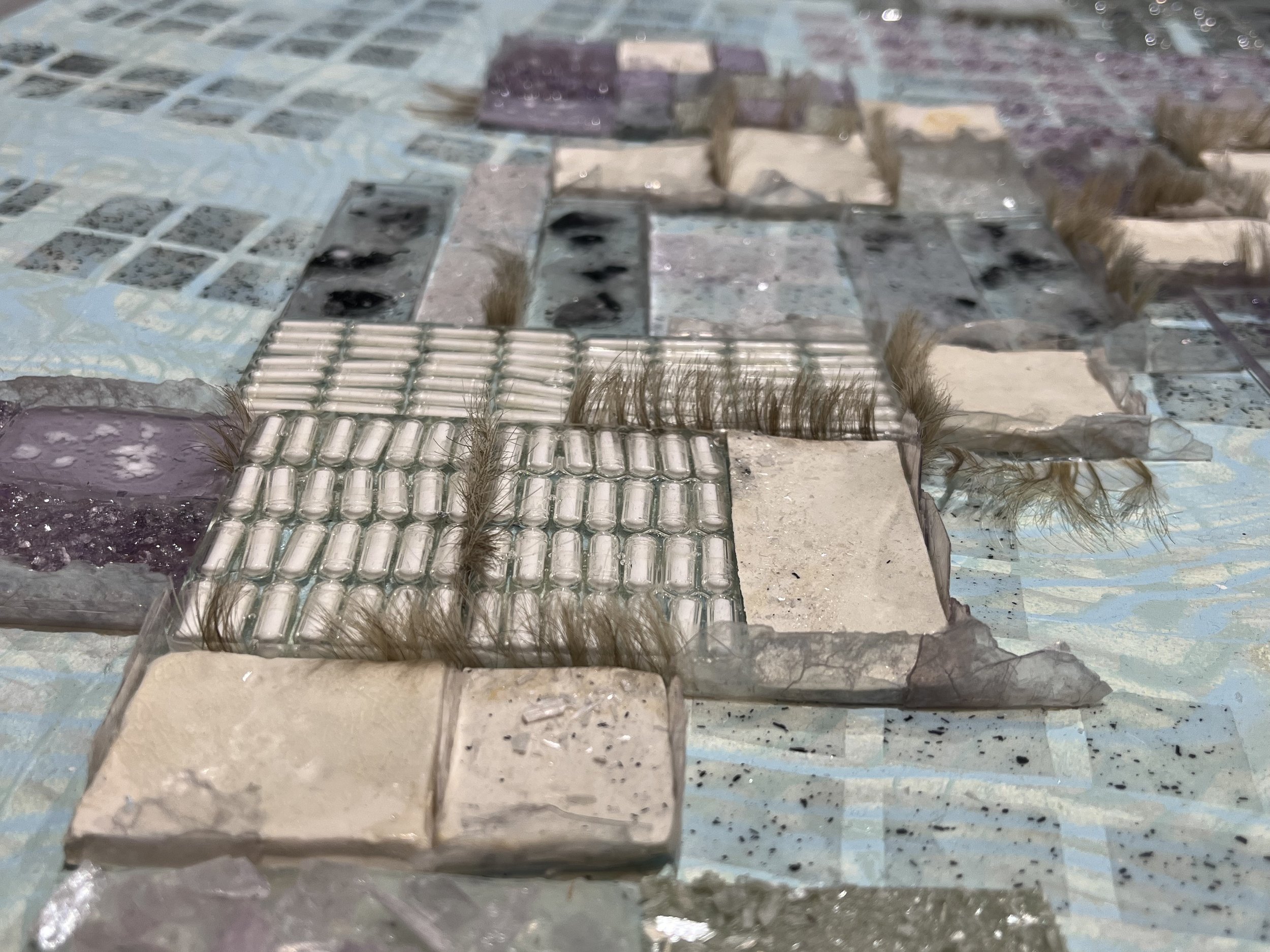

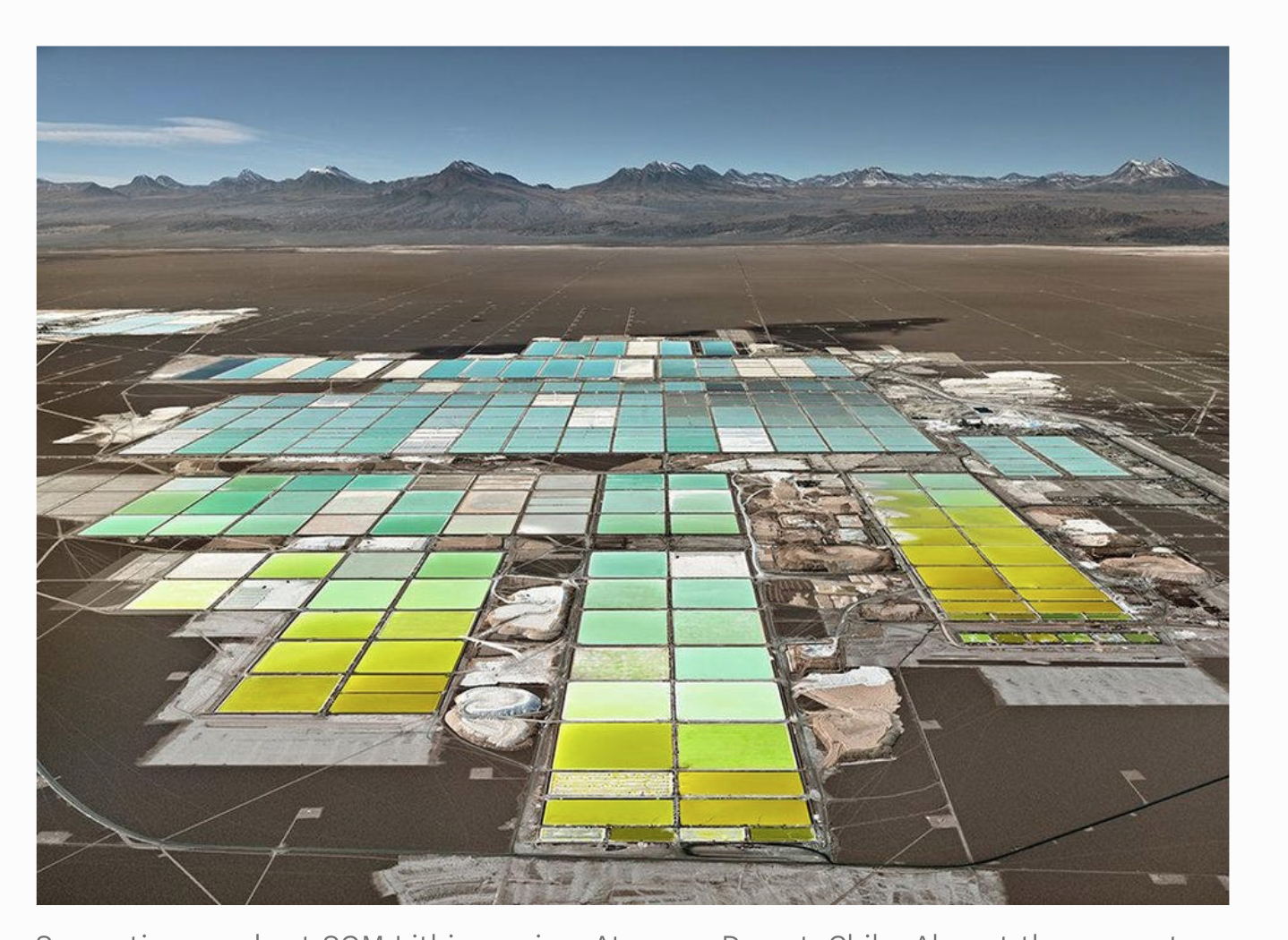

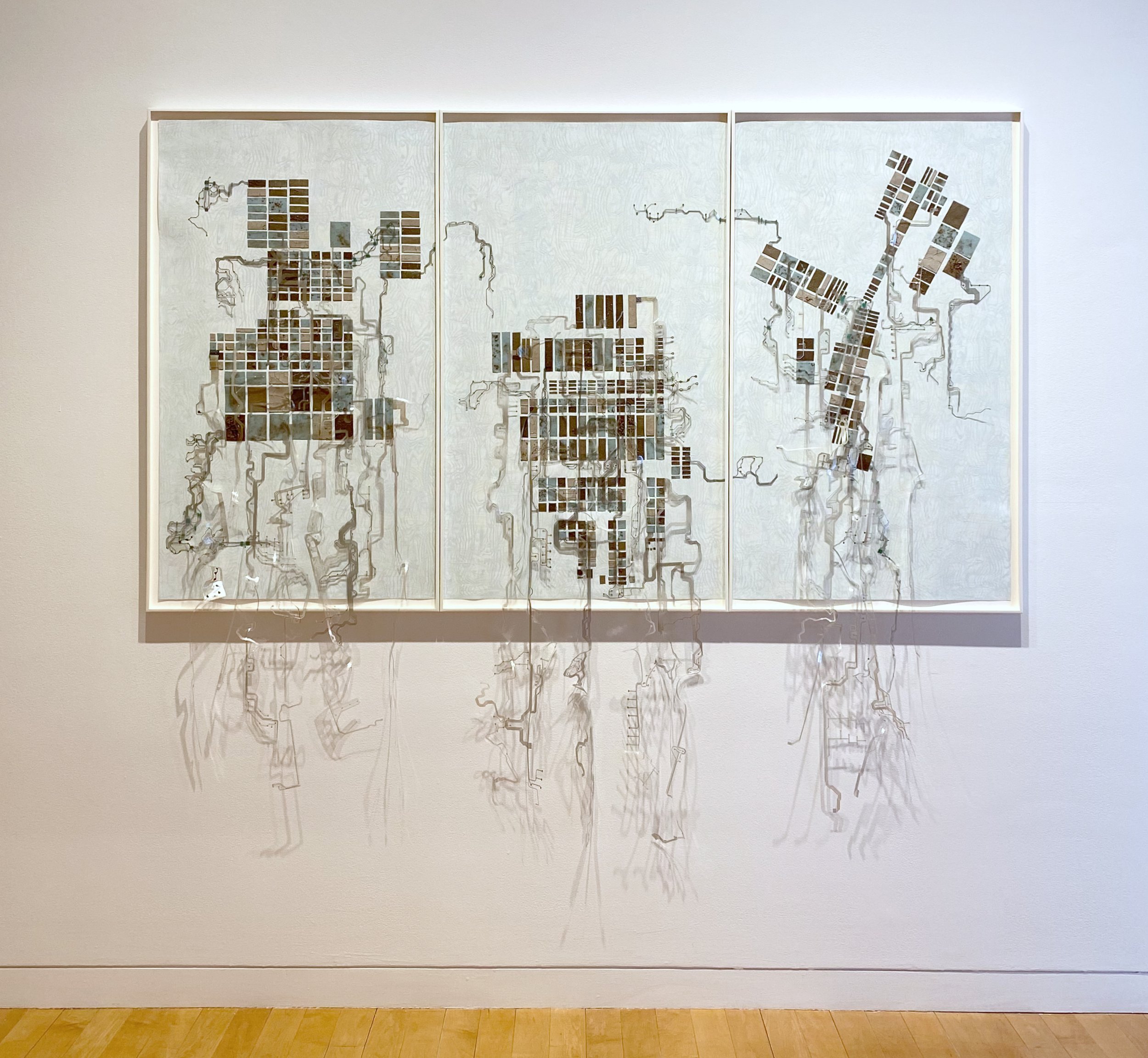

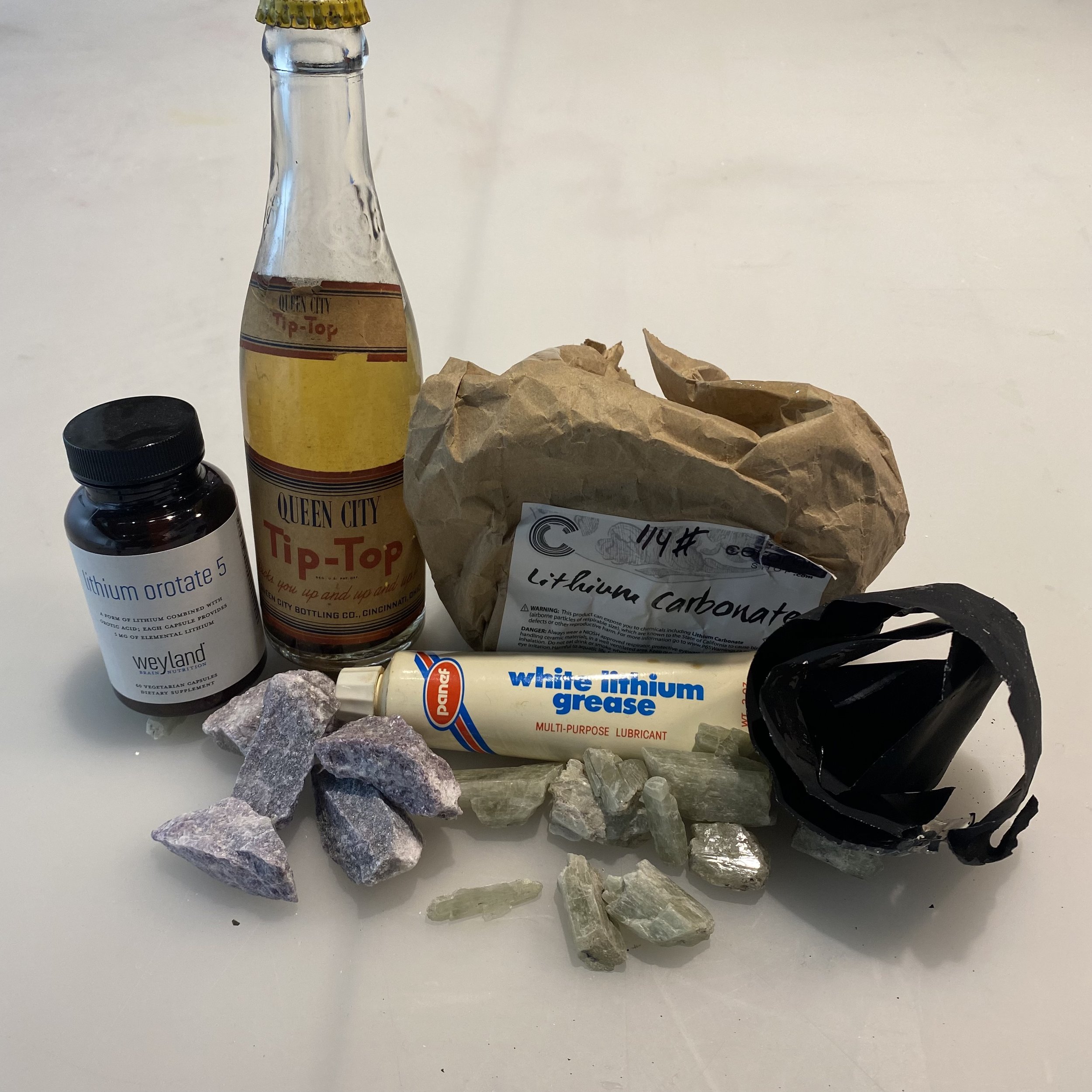

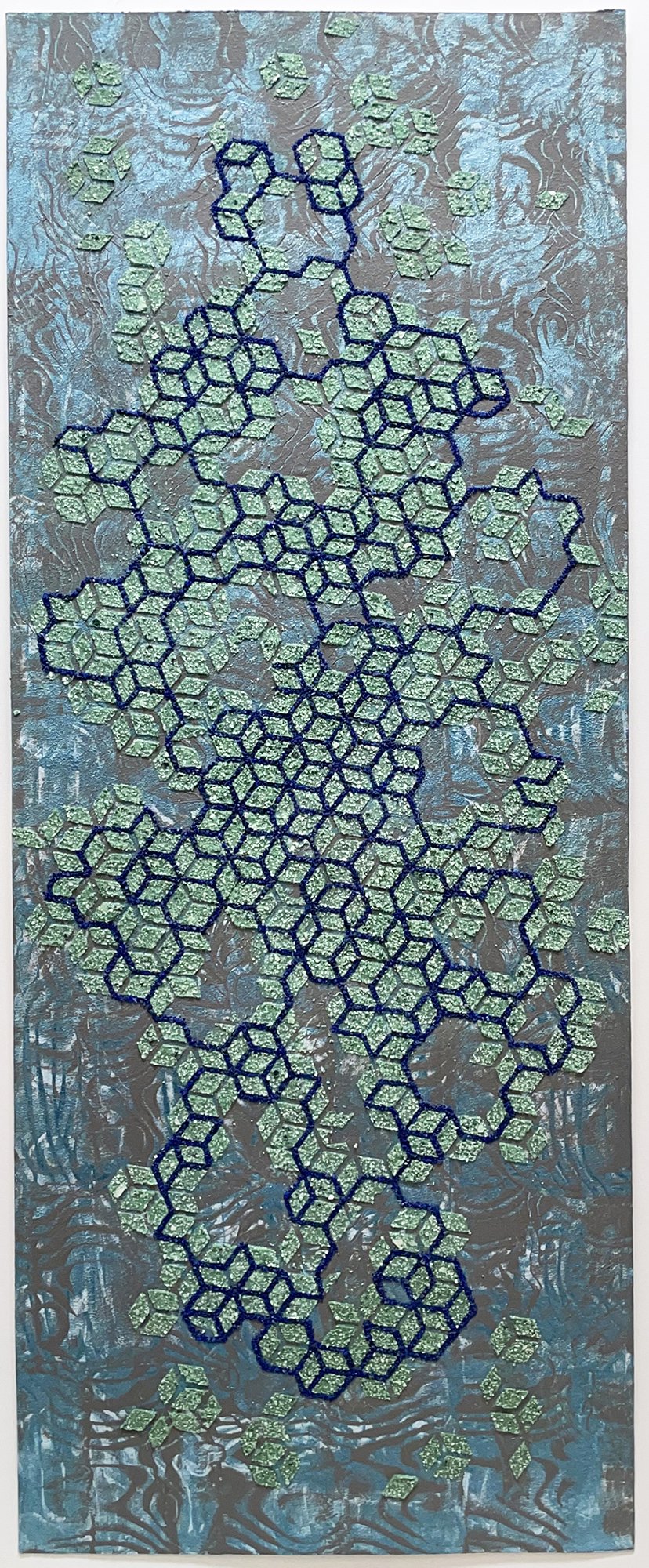

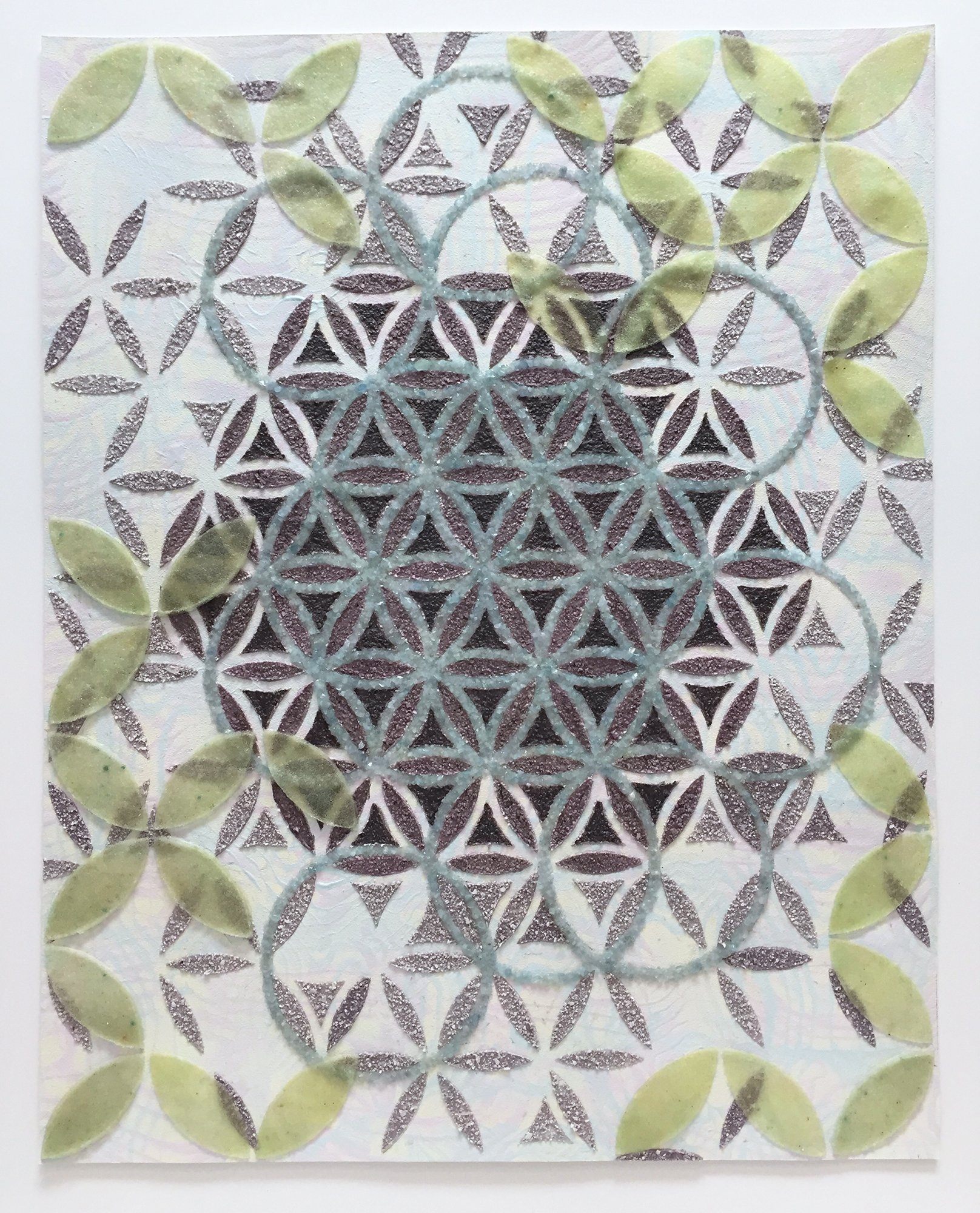

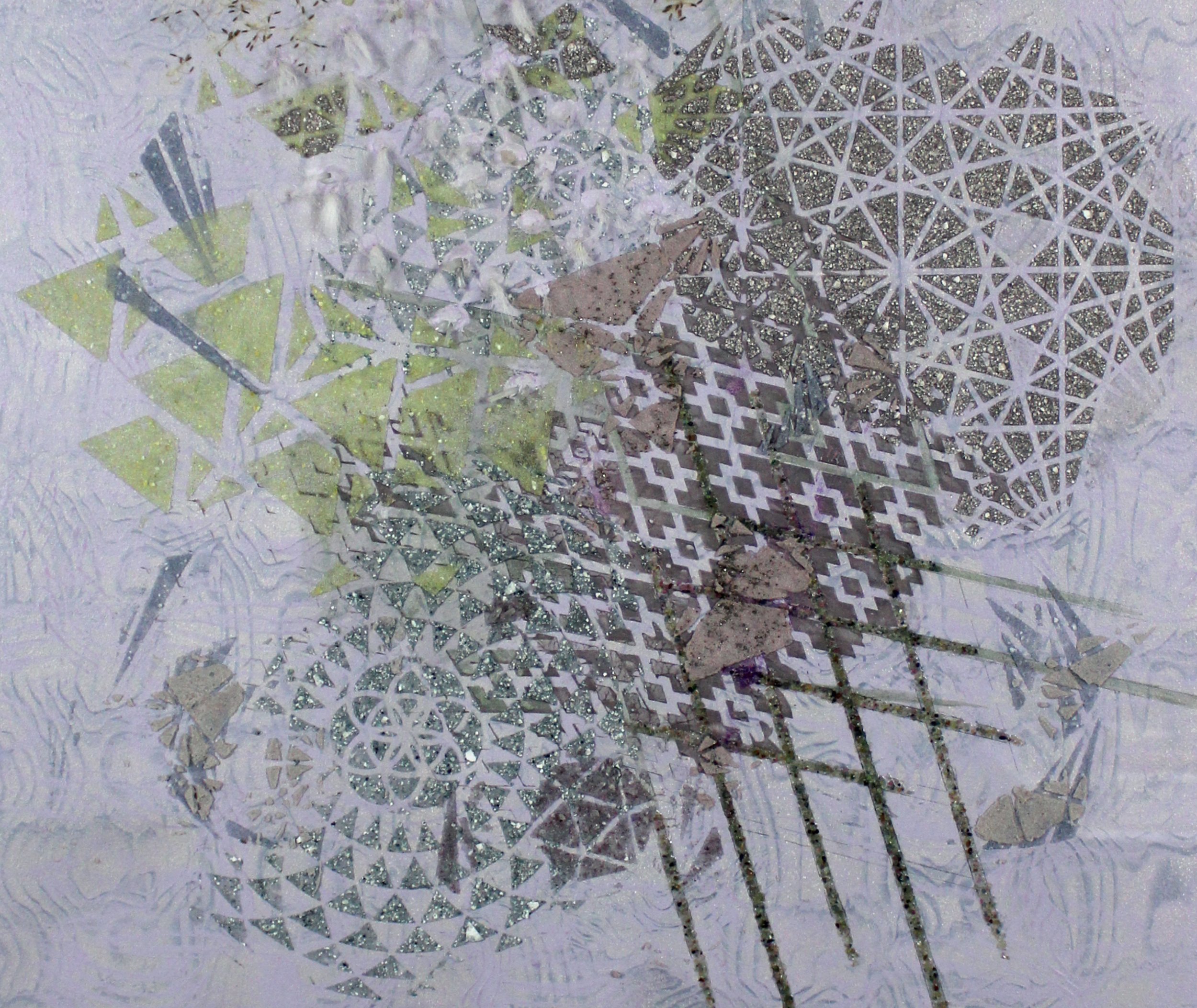

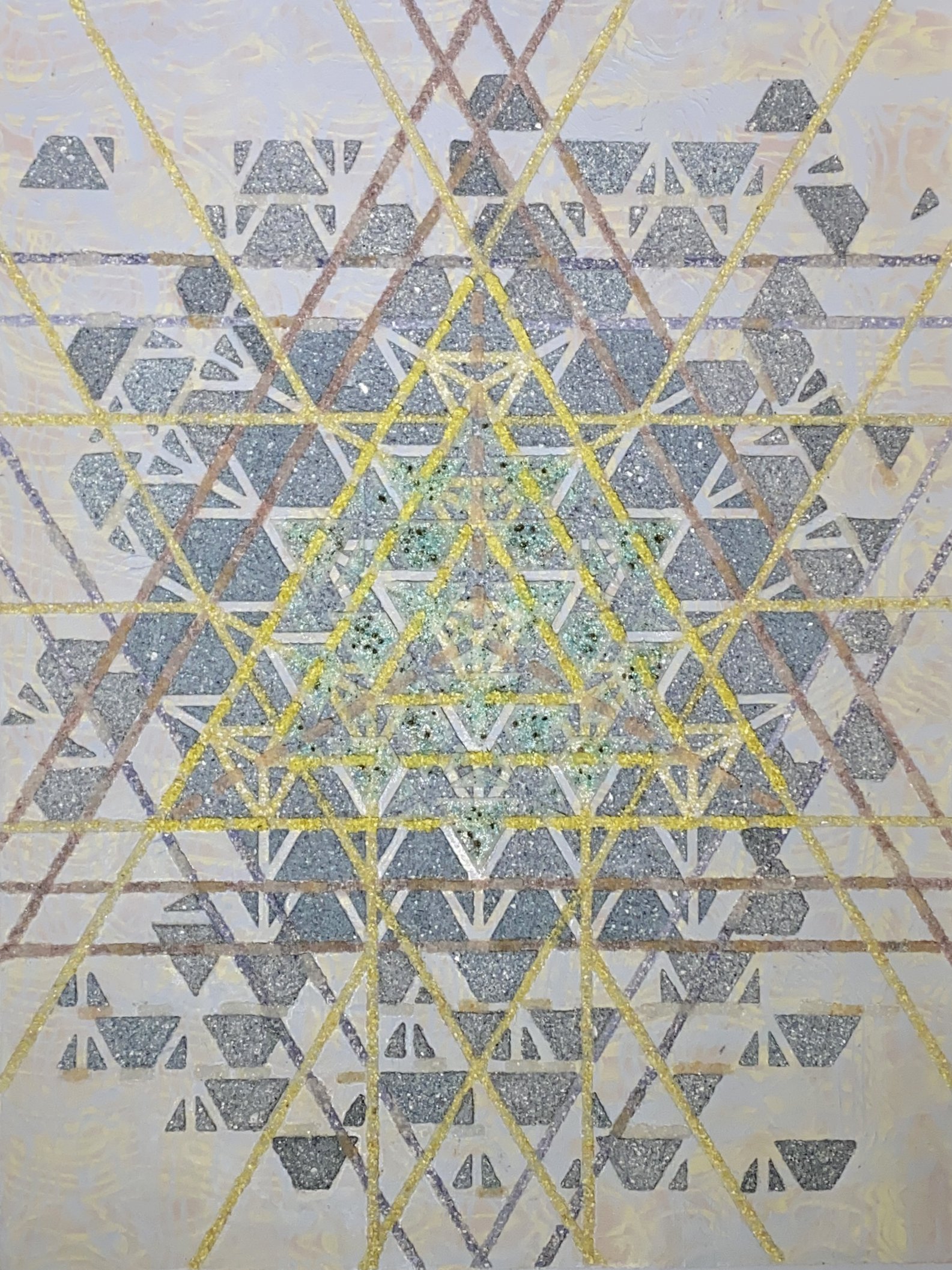

Eleanor White’s tactile works on paper may be best described as sculptural paintings, or painterly sculptures with collage elements. One of the striking features of White’s work is her use of non-traditional materials, which read as ingredients in a science experiment or herbal brew: crushed lapis lazuli, porcupine quills, dandelion seeds, eggshells, shed snakeskin, dog hair, copper, and a pinch of spodumene. In “Prima Materia”, the current show at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, White was commissioned to create two works using lepidolite, the mineral most abundant in lithium. This is the metal that you’ve been hearing about in the news, in high demand due to its use in rechargeable batteries. White’s works address the proposed lithium mine in northern Nevada, a 1,000-acre site known as Thacker Pass, as it threatens to devastate the tribal land on which it’s located. As in all her work, White went down a rabbit hole with this project, translating her research into a visual language that conveys the beauty and controversy associated with lithium. Indeed, the glittery bling of the material casts a long shadow across the Nevada landscape, which the Shoshone and Paiute tribes claim as their ancestral burial grounds. The sparkly purple of the lepidolite momentarily distracts us from the critical issue – namely, the disregard of the U.S. government in permitting the mining corporations to enter this sacred land. White takes advantage of the mineral’s optical allure to make it difficult for us to look away, and we want to engage further in the unfolding narrative. In other recent works, she creates geometric patterns using solid materials that contradict their transient substrate (crushed gems on paper grocery bags) or juxtaposes precious stones with common materials (lapis lazuli and eggshells), crushing both into granular, indistinguishable substances. White effectively levels the playing field, suggesting that all materials possess equal value, with comparable susceptibility to the laws of entropy. Whether objects of beauty or catalysts of controversy, White handles her materials with the same respect, embracing the complex issues that they signify. From rare stones to paper grocery bags, all organic materials are precious and mined at a great cost to the planet and its inhabitants. While White states that her work is not intentionally political or environmental, it invariably transcends aesthetic expression and raises complex issues that haunt us well after encountering her work.

MH: In your work you use materials that aren’t generally associated with two-dimensional work, including crushed stones, dog hair, and porcupine quills. How did you come to use these unusual materials? What was your inspiration?

EW: It naturally comes out of my sculpture practice. I’ve always used unusual materials in my three-dimensional work, but for lack of space a few years ago I started working on paper. It’s not exactly painting, but I’m working with a thick medium, and I’m moving it in the direction of sculpture.

MH: Do you think of your works on paper as sculptures? They’re sort of between two and three dimensions.

EW: Yes, because I’m using the same techniques: casting, collage, and so much is about the materials and my curiosity around working with them.

MH: The materials you work with are unfamiliar to most people. Like, most people have never heard of spodumene. Has this been a process of discovery for you? And is the research part of your practice?

EW: Minerals such as lepidolite and spodumene have been a point of discovery for me, as they’re a source of lithium, which is so controversial right now. The element lithium is what my two pieces in the Aldrich show are about, and they were very much research based. Before that, I was working with crushed gemstones, so it was a natural jump. But the deep dive into lithium has been interesting because it’s a current subject in the news, and it’s one of the elements that’s come to the forefront in terms of importance for our future.

MH: Why is it so controversial?

EW: Resource extraction is controversial, especially for the indigenous people who have to deal with the devastation to their land. There’s a proposed lithium mine that’s in the beginning phase of construction in northern Nevada on land considered sacred by the Paiute and Shoshone people. This would be the largest domestic mine and a huge source of lithium for the U.S. Creating the pieces made me feel a lot of empathy for the affected communities, like how would I feel if it was the Hudson Valley that was about to be devastated?

MH: What made you start using the crushed gems?

EW: It came out of the desire for more permanence. I was using eggshells and ash, which captured the idea of impermanence, but I wanted to go in another direction by adding color to my work and using a more permanent material.

MH: Would you describe your process? What are the challenges around using these materials, and then attaching them to a surface?

EW: In my exploration of works on paper I started thinking about what I could do that’s not exclusively a painting: what do these materials have that paint doesn’t have? The crushed stones are granular, they have dimensionality, and I can mix them in a casting process with molds and medium. But the big challenge is coming up with the composition, so I make these little pieces and move them around the paper for a long time until a design emerges.

MH: Wait, you don’t mean that you make those little piles ahead of time, do you?

EW: I do. I cast them all on sheets of plastic then rip them off, then I can move them around on the paper to create the patterns. I started out doing it with stencils and did it in one shot, but I rarely work that way anymore. I’ll frequently have several pieces going at once because it can take so long to come up with the composition.

MH: I’m intrigued by the patterns that you choose. They seem at times to derive from Islamic geometry, and other times they read as complex mathematical charts. What’s the inspiration behind them?

EW: There’s inspiration from Islamic patterns as well as Japanese prints and their flattening of the patterns. What I enjoy the most about Japanese prints is and how they shift without any dimensionality; the design always remains flat. There’s also a lot of mid-century design that inspires me. Both pieces in the Aldrich exhibition are abstractions of aerial views of lithium mines in Chile which are structured as grids.

MH: The show at the Aldrich includes two of your works on paper. How did you feel about the work being included in this show? Was there any reluctance in having your work cast as Prima Materia? Does that feel restricting in any way?

EW: I’m absolutely thrilled to be in the show. The curator asked me to use lepidolite, because it’s one of the stones that contains the most lithium. The color was challenging, because it’s a very alluring light purple, so I had to find the right balance for this beautiful, sparkly stone. I felt like I needed something to create a push/pull, so I included tufts of hair from a person who has taken pharmaceutical lithium in the piece. It adds a creepy quality to the work, and I enjoy the balance of attraction/repulsion in the different materials. The purple piece “All That Glitters (is not gold)” involved research into a wide variety of materials that contain different forms of lithium. The other piece, “Between and Rock and a Hard Place” was me thinking about the Thacker Pass proposed mine site.

MH: There are a lot of metaphors that could be associated with your work. How do you think about it? Do you have a conceptual overlay, or is it more about the aesthetic appeal?

EW: It’s a combination of both. I want it to have aesthetic appeal, but I also want the work to resonate on a deeper level. I want people to think about it after they’ve left the museum, and to stay engaged.

MH: Does your work make any statement about the environment, the devastation of the planet, scarcity of materials, that kind of thing?

EW: Definitely. But I try not to be overtly political or heavy-handed. I don’t think that works for me.

MH: The angle that I’m most interested in exploring is the precious nature of your materials. Is that a consideration in your work?

EW: I do now! At first, I was drawn to them for the color, but now I’m thinking more about where my materials come from. It creates tension for me to think about it in this way.

MH: There’s the idea of high and low art, one being loosely based in a work’s market value, and the other more about pure expression, with no regard to marketability. I can see your work making a statement about this, but I don’t want to assign meaning if that’s not your intention.

EW: I’m not using gems for their value. I started using them because I thought they’d be more permanent. I was using playing cards previously and didn’t realize that the inks were fugitive. I didn’t think gems would fade or change, but as it turns out, some gemstones fade. But I see all the materials as equal in terms of the interest it holds for me.

MH: You did a series where you glued crushed gems to the brown paper bags that you get at the market. This material is non-archival and it’s an interesting juxtaposition between materials: one is precious, the other disposable. What were your intentions around this?

EW: I did those during the pandemic, and that was the paper that I had on hand. I wanted to do things much faster, because I wasn’t very focused at the time. I was also trying to loosen up, because my work can be a little formally tight, so it helped with that, and it also helped take my mind off the pandemic.

MH: Are you concerned about the longevity of these pieces? Does it matter to you that the acid will break down fairly quickly?

EW: I think about that in all my work. I talked to a conservator about artists’ materials, and their opinion was that artists should be more concerned about creative expression than anything else. But the idea of permanence, whether it’s conceptual or actual, is of interest to me.

MH: In what sense?

EW: How it relates to us, how it relates to time. And now I’m thinking about it in terms of whether I want it to be around, or if I just want it to dissolve. Leave no trace, right?

MH: That’s interesting. I’ve never heard that point of view before. Most artists obsess about which museum or landfill their work is going to end up in once they’re gone, but the idea of making something that will intentionally self-destruct is intriguing.

EW: Yeah, I mean there’s some guilt in making all this stuff and leaving it behind. When my work dissolves, the minerals will go back into the earth and the paper will break down. But using anything plastic-based is hard to reconcile.

MH: How do you feel about art being cast as a valuable commodity? Or the relatively new cultural phenomenon of branding? Are you good with it, or does it make your skin crawl?

EW: It definitely makes my skin crawl. It’s nice when someone wants to live with my work, but the commodification is hard to swallow, and the whole consumerist thing can be difficult.

MH: Right. Some of your materials are considered precious because they’re stones, which are commodities that people buy and sell. And lithium is a major commodity, which is probably super expensive?

EW: It might get more expensive if the demand for its use in electric car batteries increases. I think there could be a lithium rush. But the commodification of the stones – that’s not something that I’m thinking about. All the materials have equal value to me. I can be just as excited about working with beach pebbles or dirt as with garnets.

MH: It sounds like even though you’re using precious stones in your work, you don’t see the work as precious.

EW: No, and if the work looks precious, then it doesn’t have that extra thing for me. I don’t have a good association with the word “precious”.

MH: It’s a derogative term when it comes to art.

EW: Definitely. So I like to balance whatever preciousness is there with something else. Either some formal distance, or something that chills it out and makes it almost clinical.

MH: I can see that. The last thing that most artists aspire to make are objects or paintings that will be be sold in expensive department stores. Do you think that when art becomes a commodity, some essential quality lost?

EW: You mean like if you’re just pumping them out and selling them? I think an essential quality for the artist would be diminished, because you’re not learning as much from it; it just becomes rote and uninteresting. For the artist, the first of a series may not be as interesting as the twentieth, but for the viewer it may not matter.

MH: Like the blue-chip artist curse. People buy their work because it’s “important”, a great investment, but probably not for any sublime quality that it may have. And it may or may not go on the collector’s wall.

EW: That’s a terrible thing. After working in the museum and gallery world for my entire career, it makes me sad when a piece of art has never been out of storage, never been seen, and is not fulfilling its intention. What’s most important is the artist’s process of making it, so at least it fulfilled half of its intention.

MH: I’ve always had a hard time with the concept of an artist’s work being called “important”. To me, this speaks to market value, and has little to do with creative expression or cultural relevance. I was originally going to call my blog “In Their Studios: Conversations with Unimportant Artists”.

EW: I think the art that we make reflects what’s happening in the context of our lives, which is important to the artist. But the art world is driven by market forces beyond us. The whole commodification thing seems contrived.

MH: Do you think art communicates something different, depending on the viewing audience? Like if your work was in the Natural History Museum versus MoMA, the context would make it all about the lithium, and fewer people would relate to the aesthetic or conceptual aspects of the work. And if it was in a soup kitchen, it may say something else entirely. Would you be okay with showing in non-art venues?

EW: That would be great! I’d love that. I like the thought of showing it in a soup kitchen, and I hope the work would be accessible there as well. That’s what I want my materials to convey: tactility and accessibility, and the ability to relate it to your own personal experience.

MH: Can you say a few words about your three-dimensional work? I’m particularly interested in “Spring Again”.

EW: “Spring Again” is made from dandelion fluff that I collect in the spring. I add to this piece every year so it’s always getting larger. I’ve done a couple of these durational pieces that serve as markers in my life. The other is a hair piece, made from my hair that I keep adding to it. It’s related to my life, my aging. They’re ephemeral pieces, and the hair piece has an icky, repulsive quality to it. The hairball is on a gold table with a glass dome, so it’s like a relic.

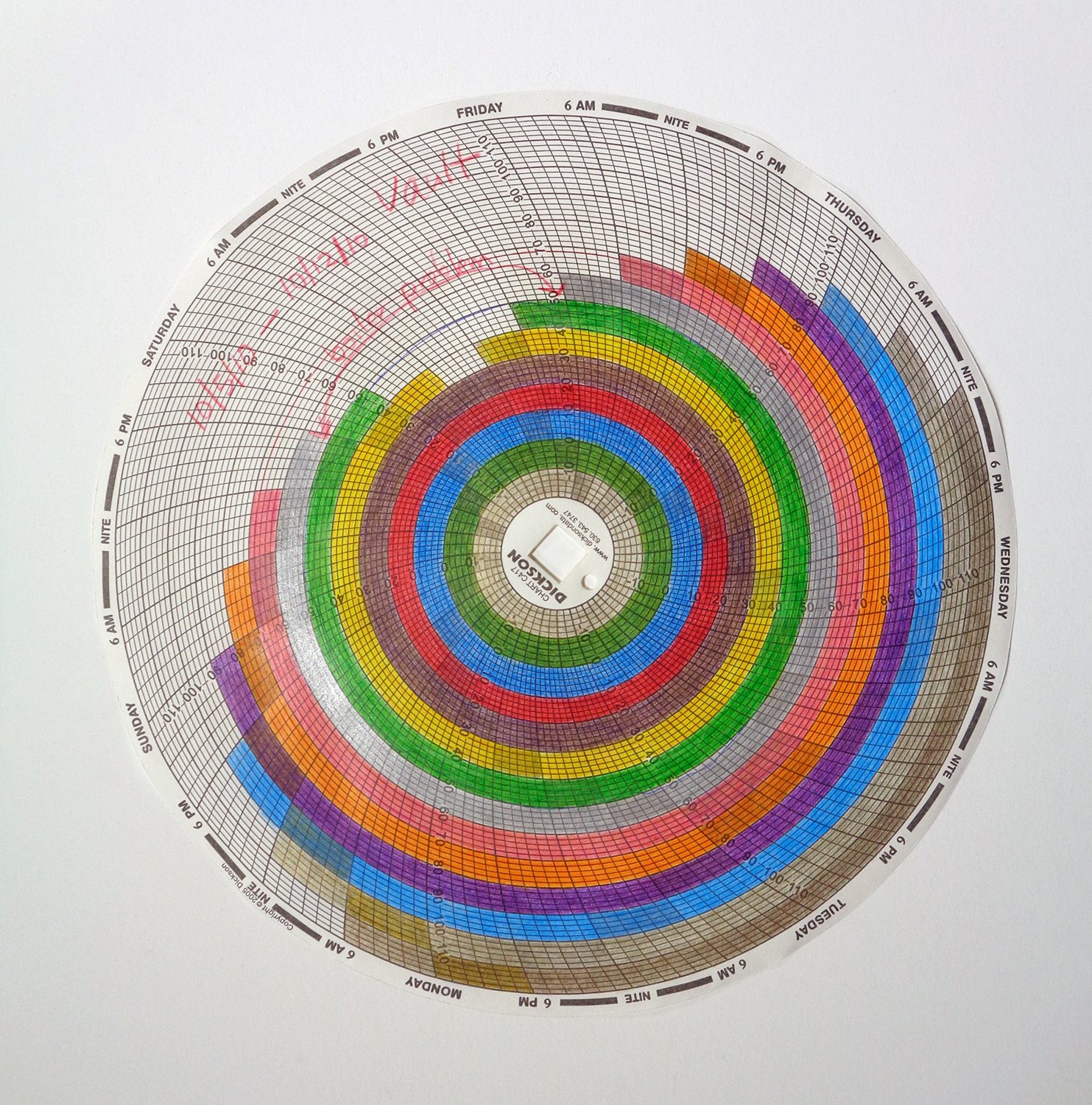

MH: What about the mandala series that you did? What were those called?

EW: Hygrothermographs. I was given these paper graphs from someone where I work. They measure the temperature and humidity in a building, but they’re no longer used because everything is digital now. I like the way these reference time, because it’s a week rotation so I’m reclaiming the time that I was at work. And I like working with color, which creates the push/pull with the clinical aspect of the charts.

MH: By clinical do you mean conceptual? You mentioned it earlier and I’m not sure what you mean.

EW: It could be conceptual, or maybe cerebral. The concept is important, but I also want there to be aesthetic appeal, so it’s a push/pull for me, finding the right balance.

MH: Your work is an interesting juxtaposition between the beautiful and the clinical. The show at the Aldrich is a perfect fit for your work.

EW: Yes, and it’s very science-based, which has always been a big influence in my sculptures.

MH: I know you have a show coming up at Kenise Barnes Fine Art in August. What works will you be showing there?

EW: I’m currently working on a series of pieces based on the four elements: earth, air, fire, and water, and loosely inspired by or evoking the feeling of those. I’ve completed “Earthbound” with crushed stones, porcupine quills, shed snakeskin, and bonded copper and “Up In The Air” has feathers, a wasp nest, pollen, dandelion seeds. This current work with three-dimensional materials incorporated into a work on paper is a mixture of painting, sculpture, and collage. Each material I choose poses a question of how do I leave some of its recognizable qualities and still transform the materials so there’s a sense of discovery for myself and the viewer?

MH: What’s the best part about being an artist?

EW: The pleasure and grounding effect it has on my personality. It makes me feel whole, and if I don’t make art, I become cranky and unpleasant. The excitement of trying something out, testing new ideas and working them out – that’s the most fun part. Time is precious and I don’t want to waste it, so that’s one of the most difficult things, because I can’t rush the process. It’s hard when something fails, but maybe it’s not a total fail, maybe you learned something that you can take to your next piece. Art can be the most joyous or the most painful experience.

www.eleanorwhitestudio.com

“Prima Materia: The Periodic Table in Contemporary Art” is at The Aldrich through August 27th.

”Bet They Collect Things Like Ashtrays and Art” opens at Kenise Barnes Fine Art on August 26th, and runs through October 15th.