MH: You work with mixed media, but your primary material is fabric. What’s the story behind that?

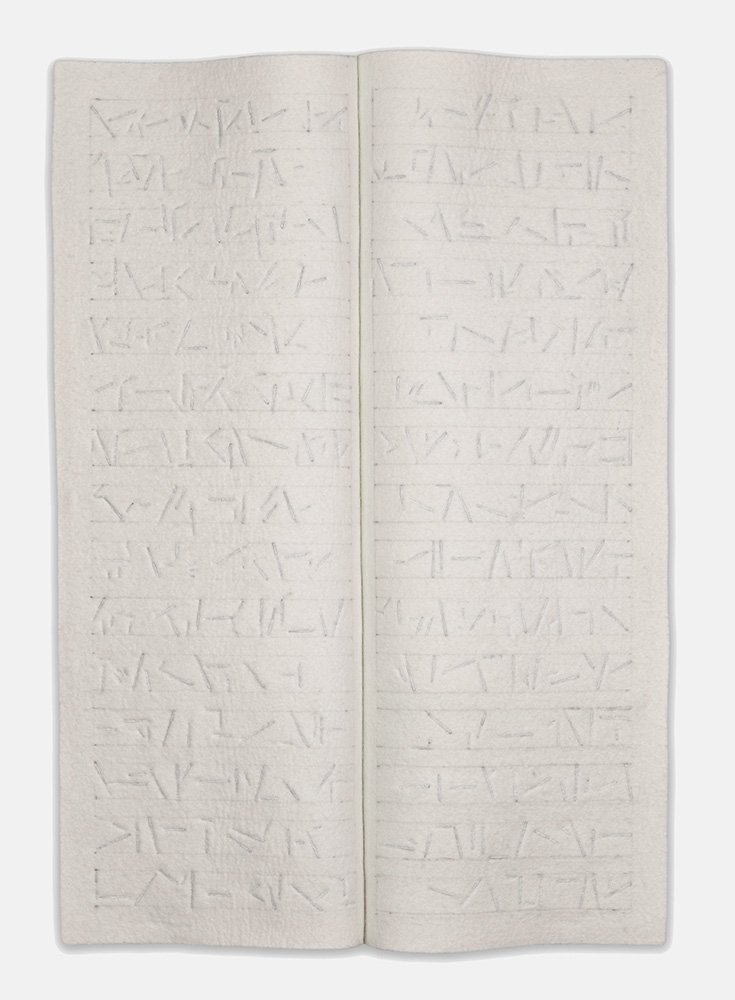

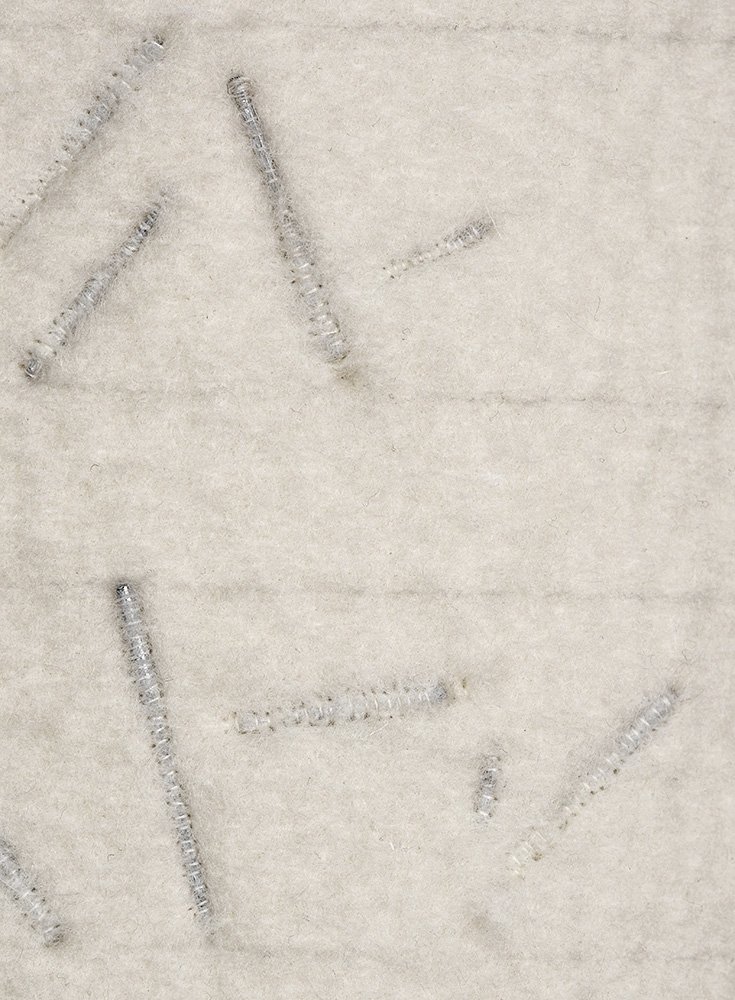

RC: I have a long history of working with fabric. When I was a little girl, I didn’t like my clothes, so I altered them into what I thought my clothes should look like. Also, at that time in Pakistan there were seamstresses who would come to your home and sew clothes for you, so you could sit by them and tell them how the design should look. This was a common practice – people didn’t go out and buy readymade clothes. And then my grandmother taught me how to make dolls by stitching and stuffing fabric. It was a very crude way of doing it, but it gave me some ideas of how to make my own dolls. So from a young age I was very comfortable with hand stitching and altering clothes.

MH: Did you experiment with other materials in art school?

RC: When I went to art school at the National College of Arts in Lahore, there were only traditional sculpture materials like clay and bronze, so I didn’t work with fabric at first. Then my mother became very ill so after graduation I was her caretaker for 11 years. There were heaps of discarded clothing from my family in the house, and I started working with this fabric by hand sewing it. I knew that my mother wasn’t going to be around much longer, and I wanted something to remember her by, so while she slept I started making hand sewn dolls that looked like her, with round curves and a long braid.

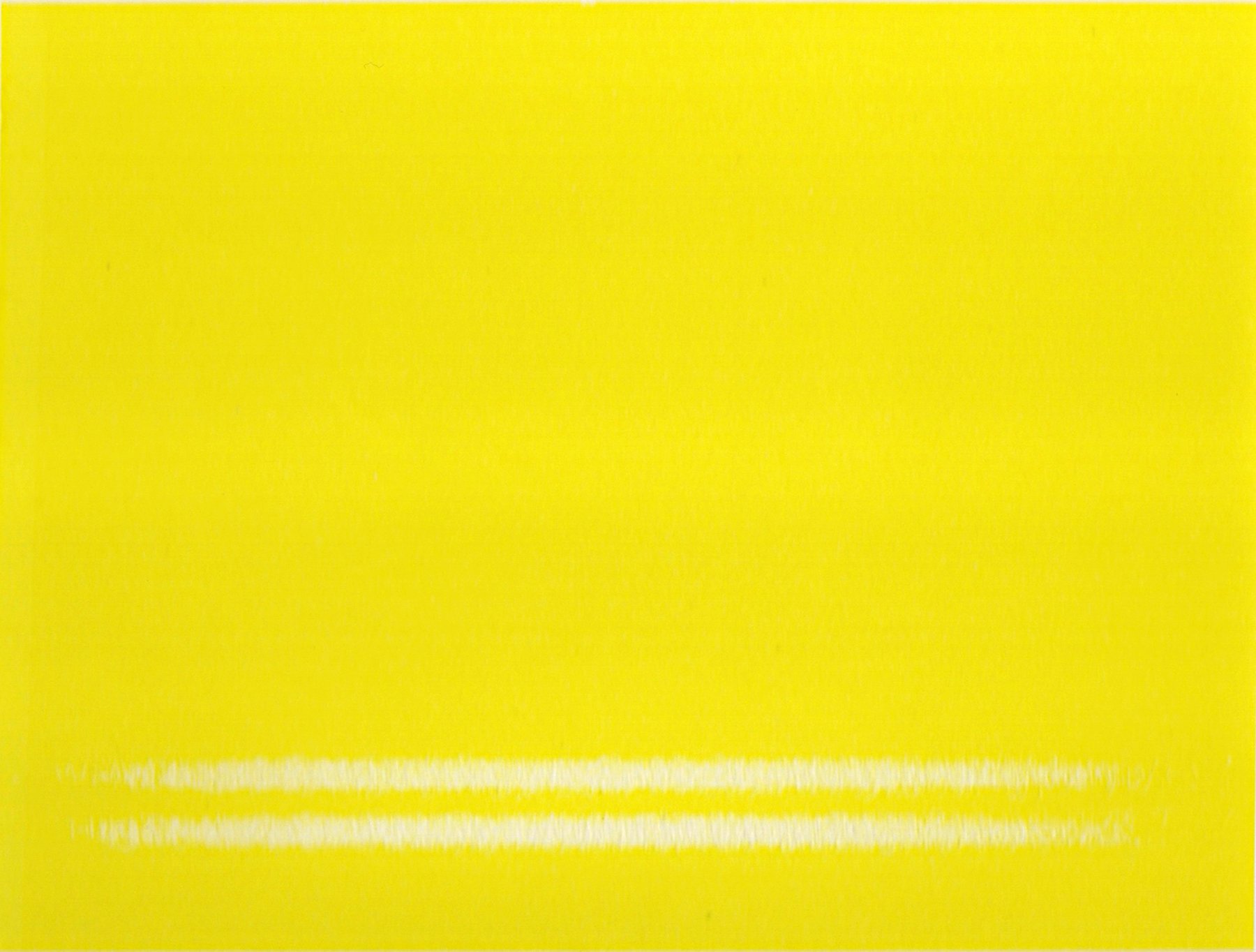

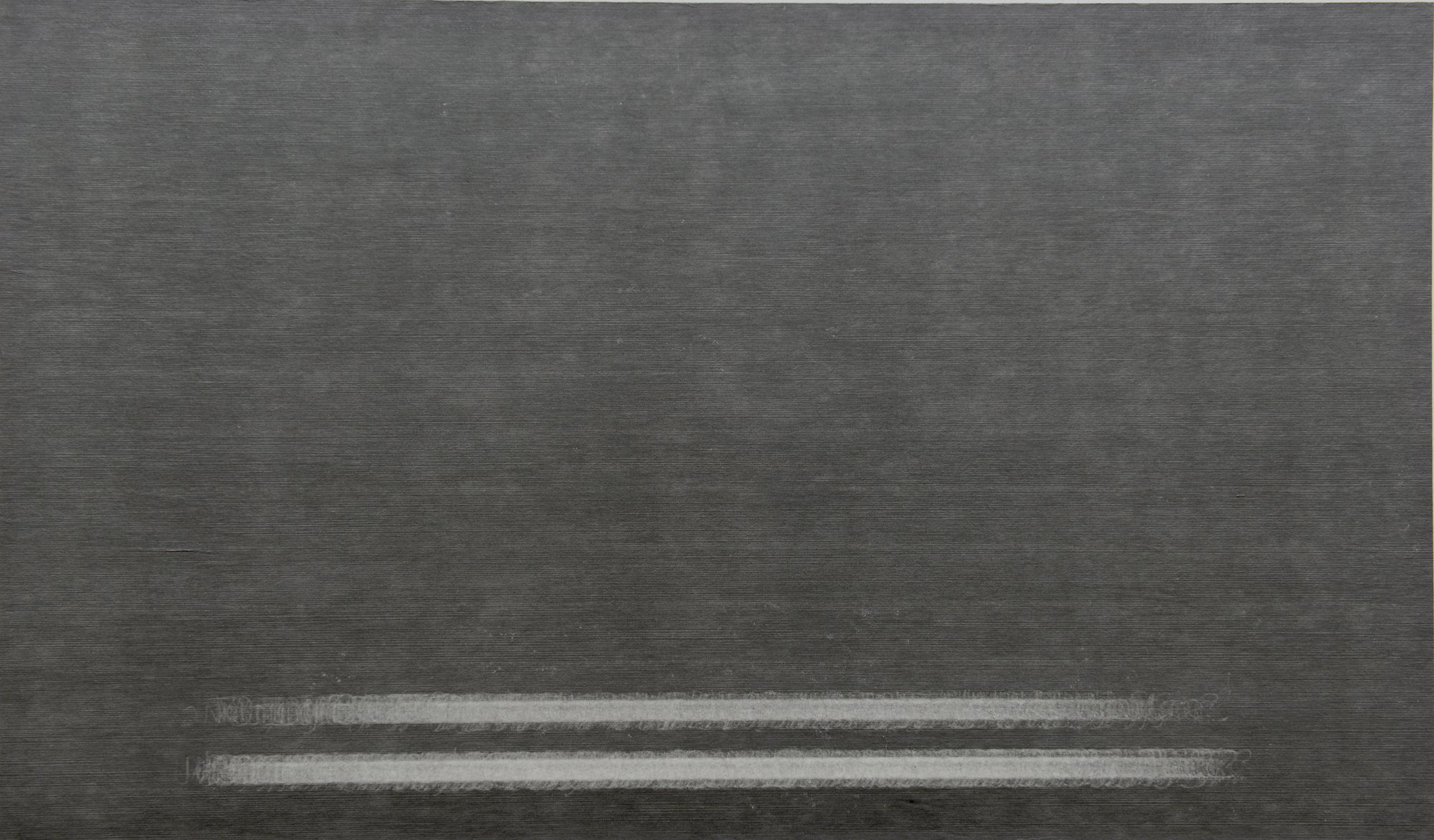

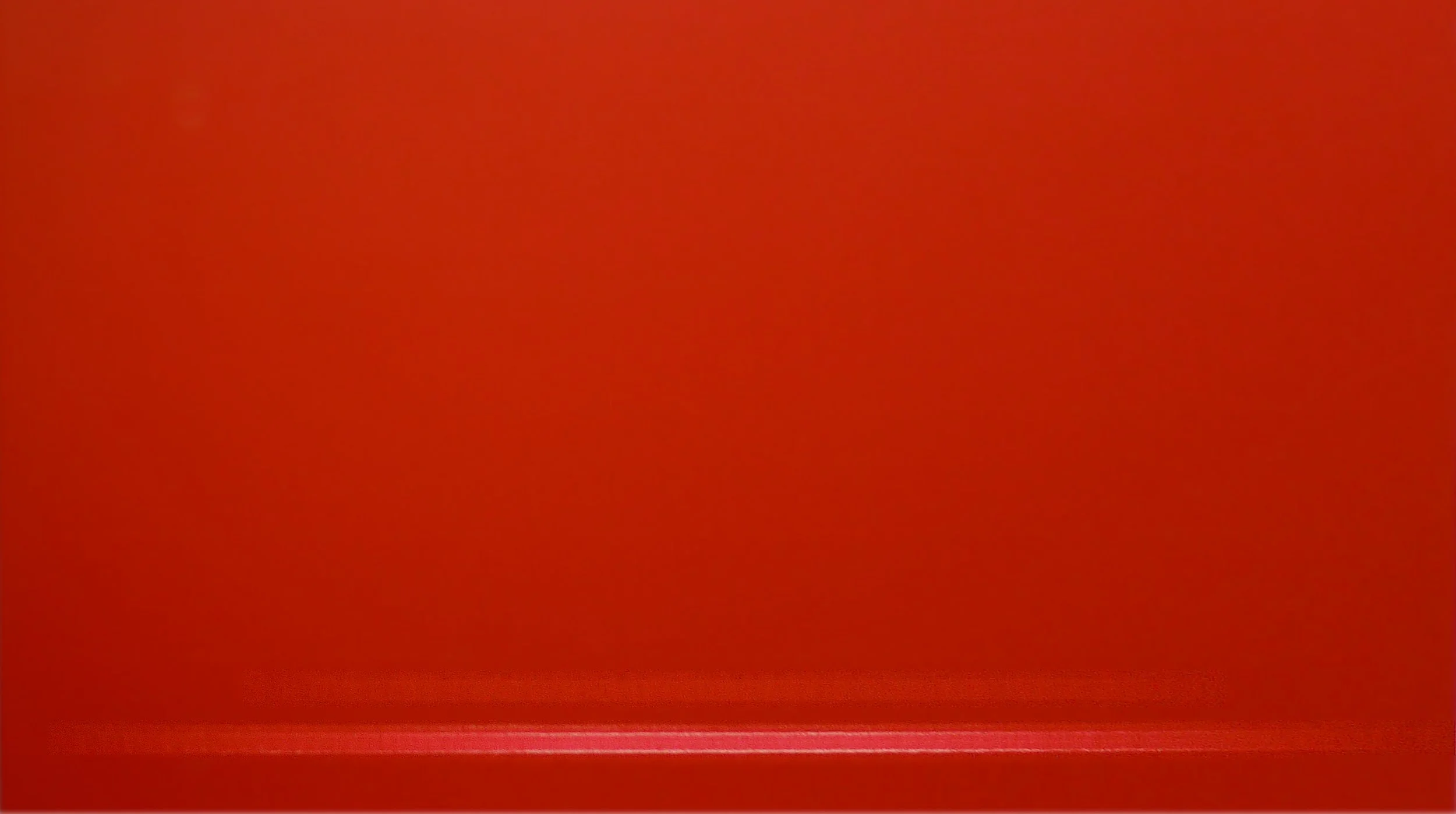

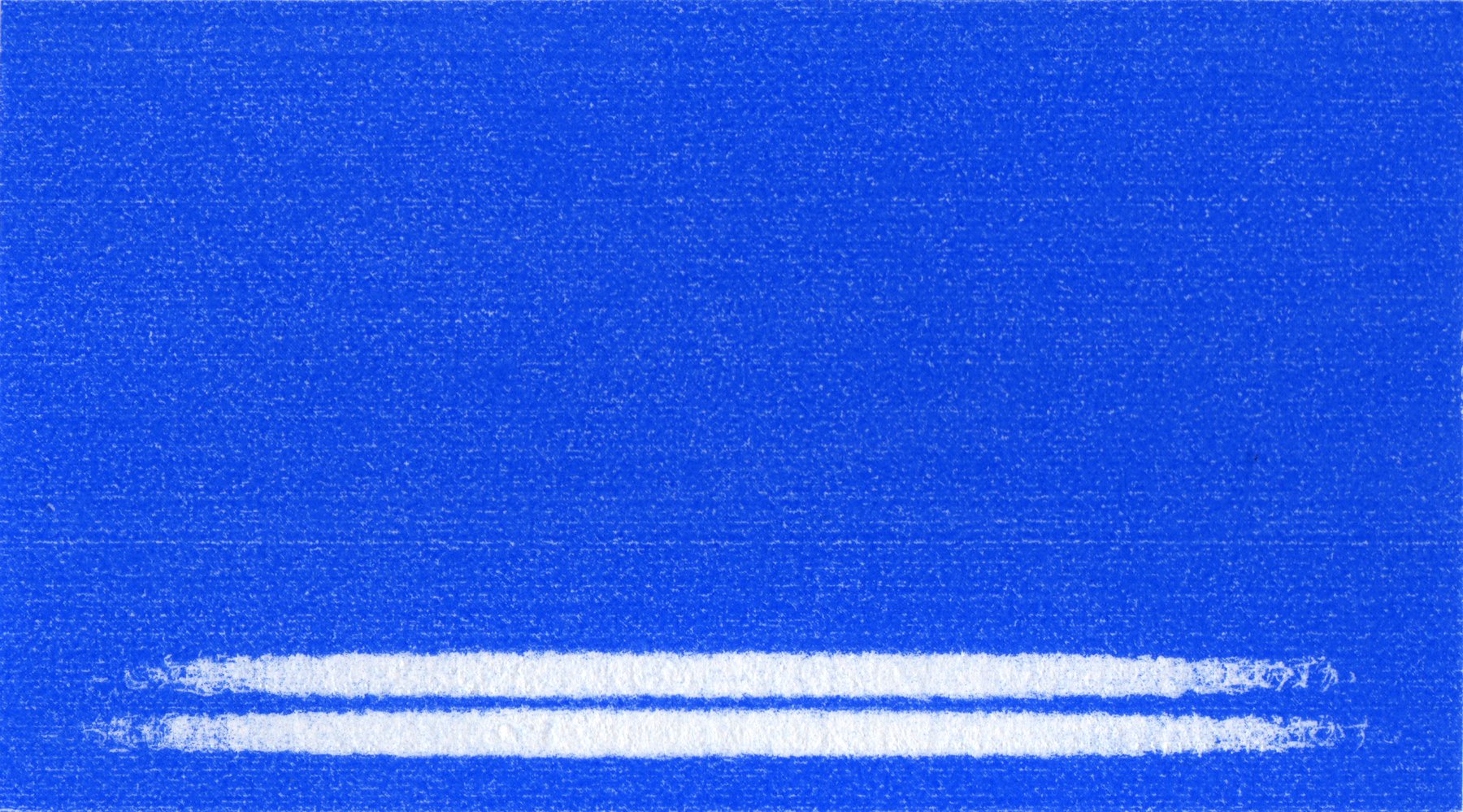

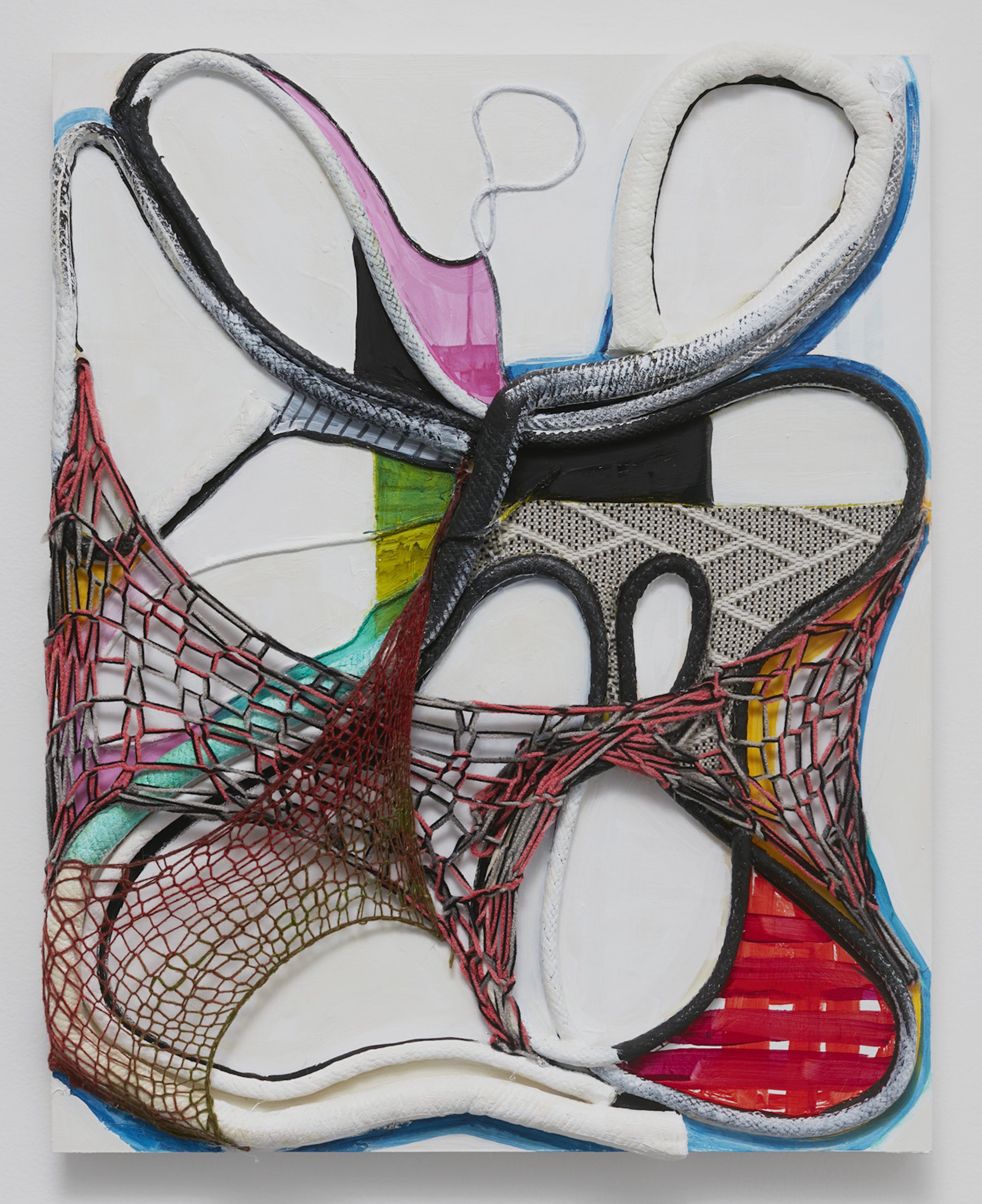

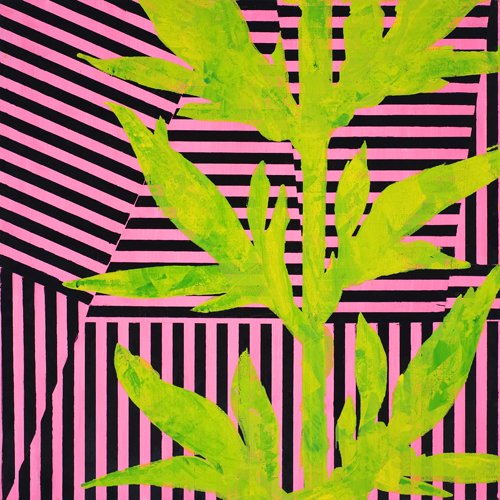

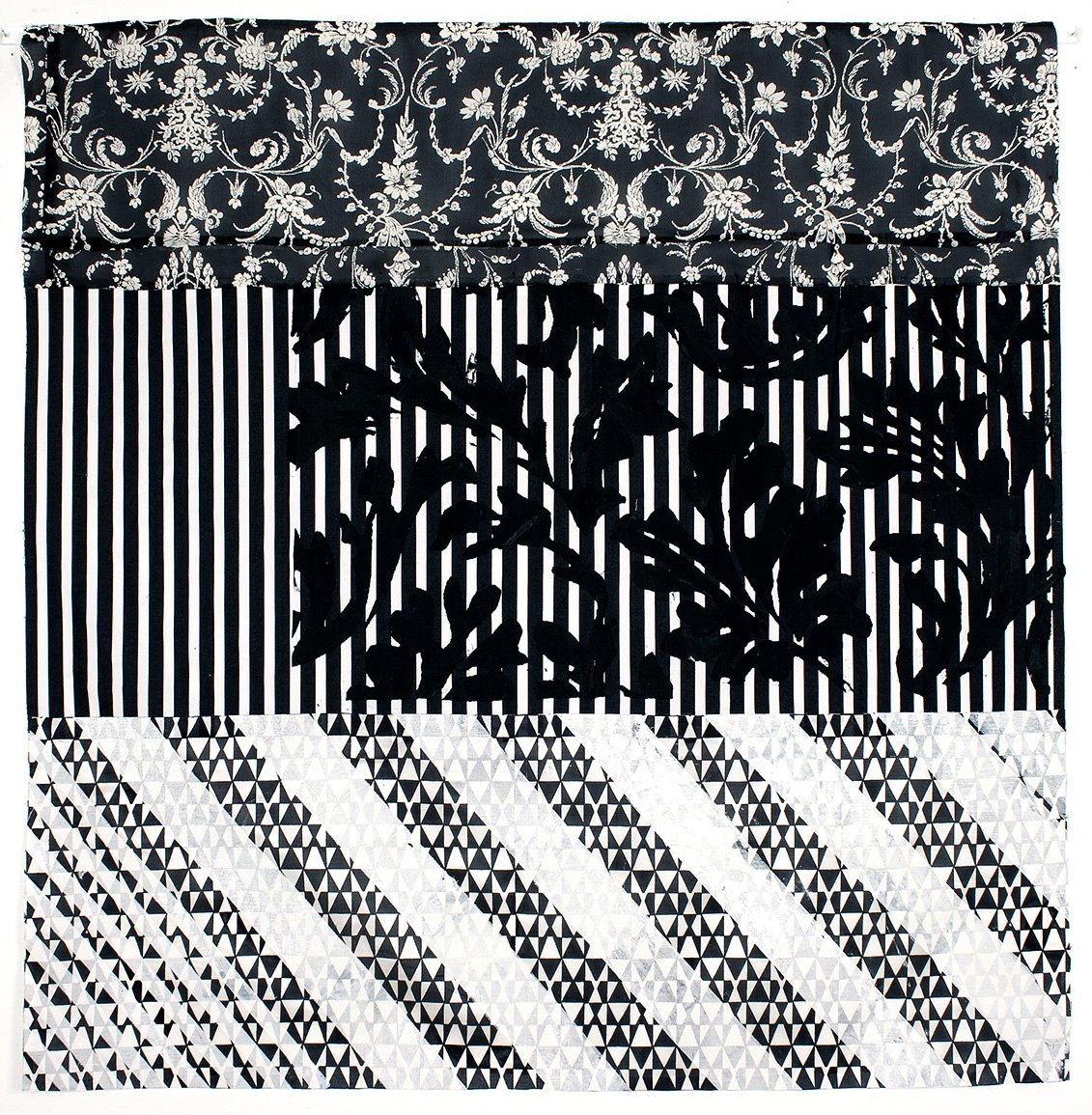

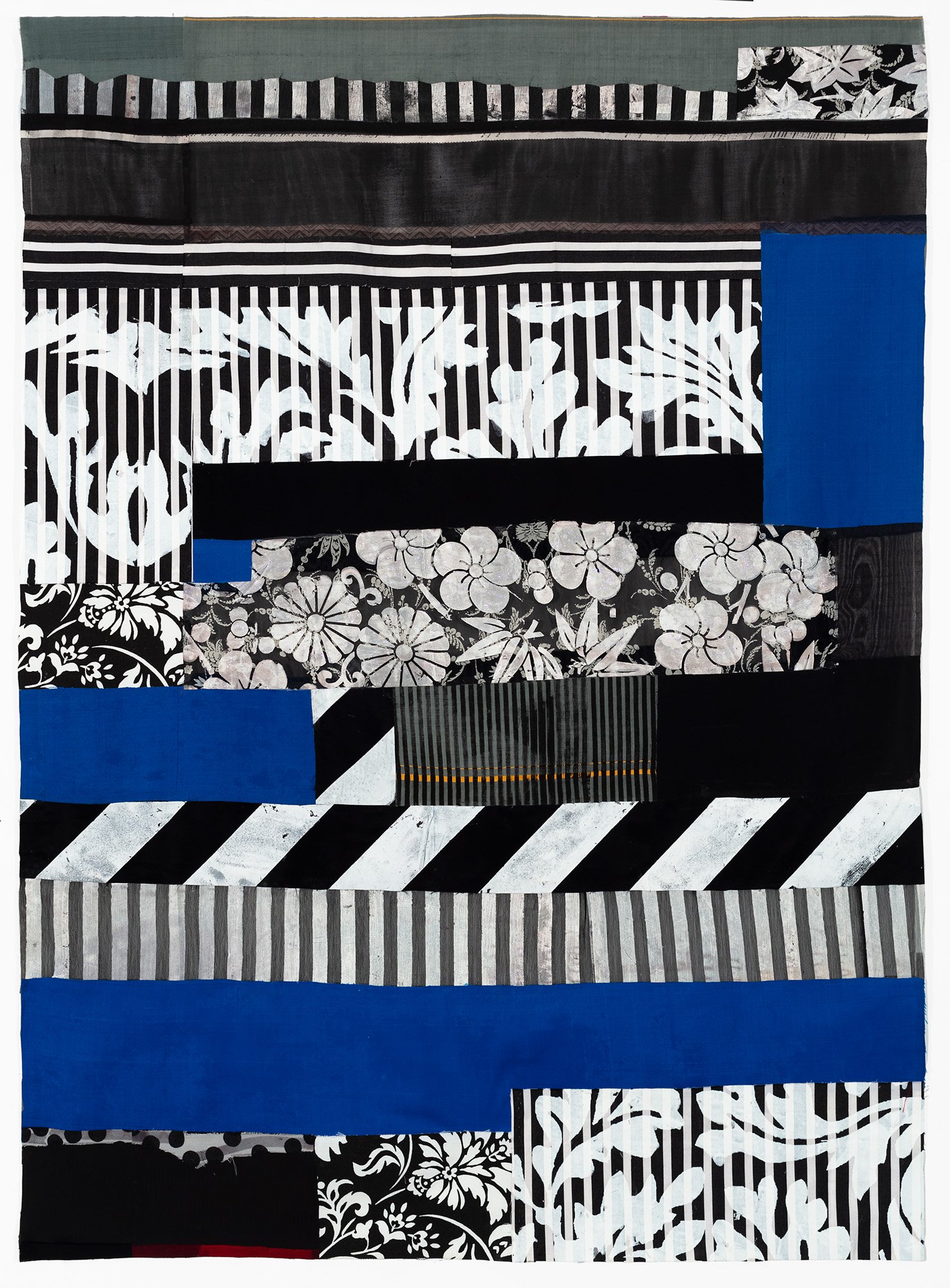

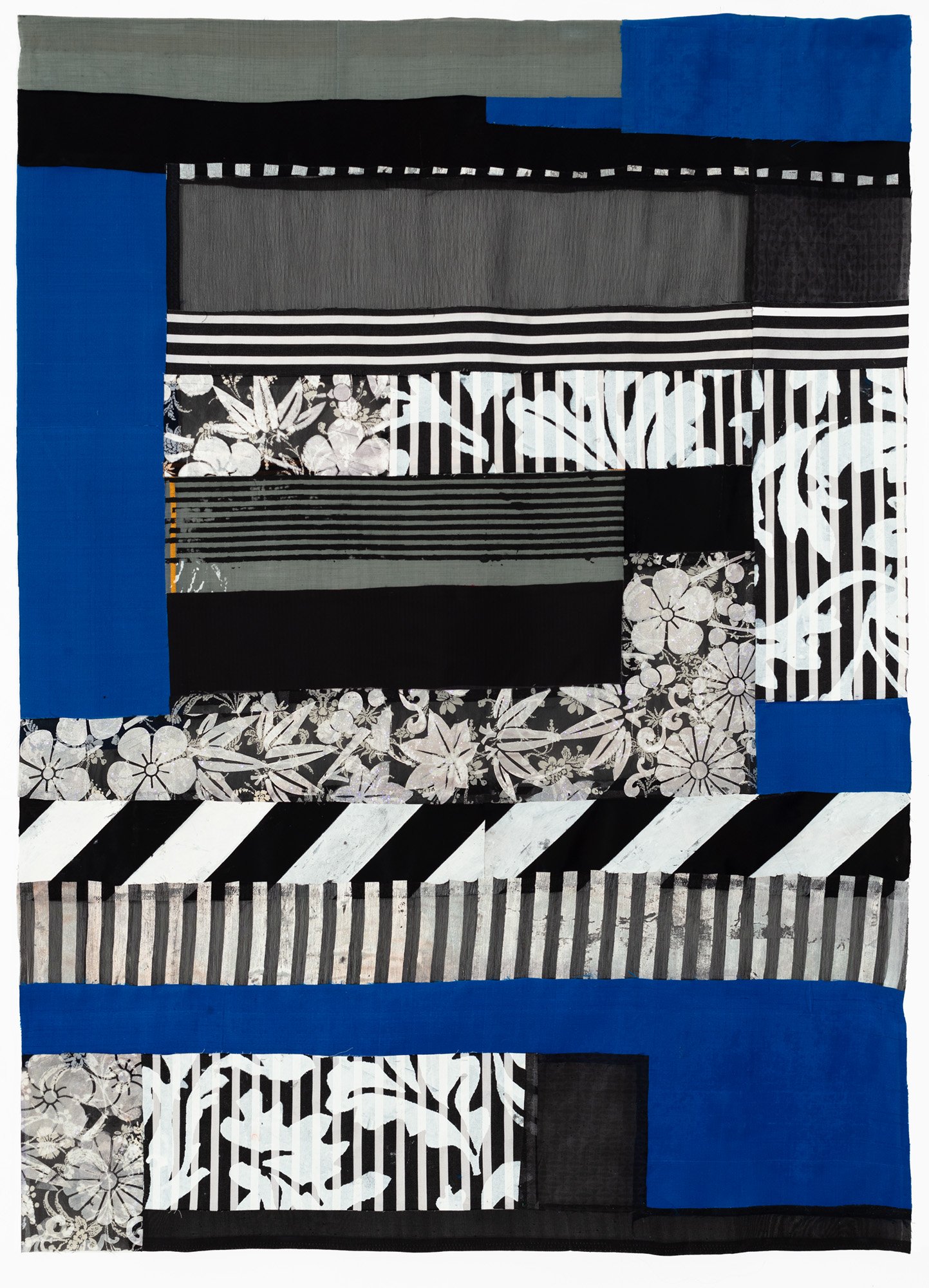

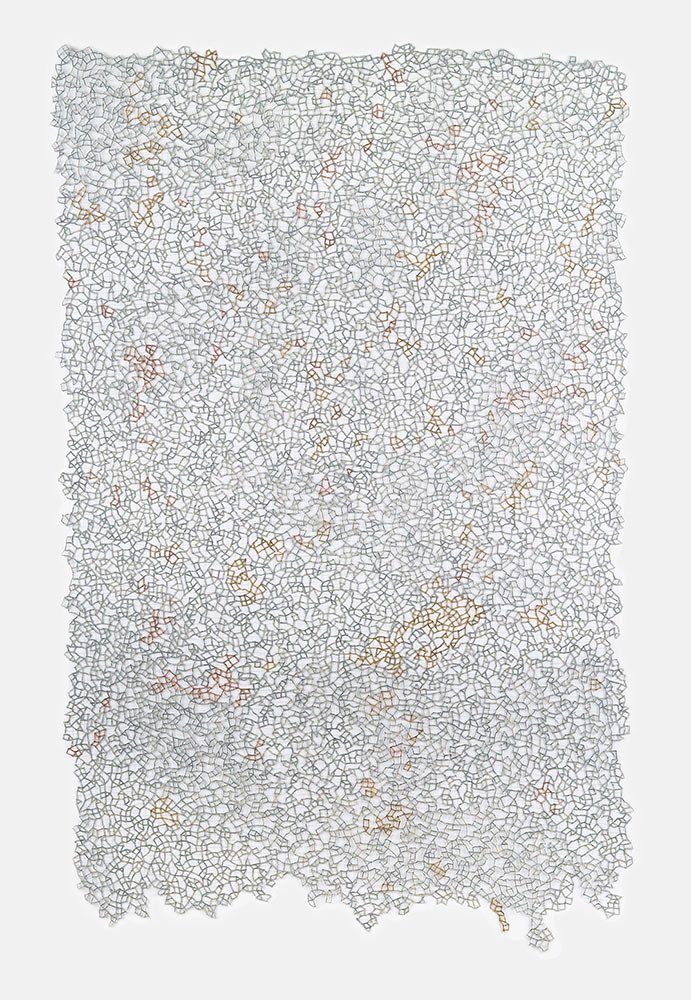

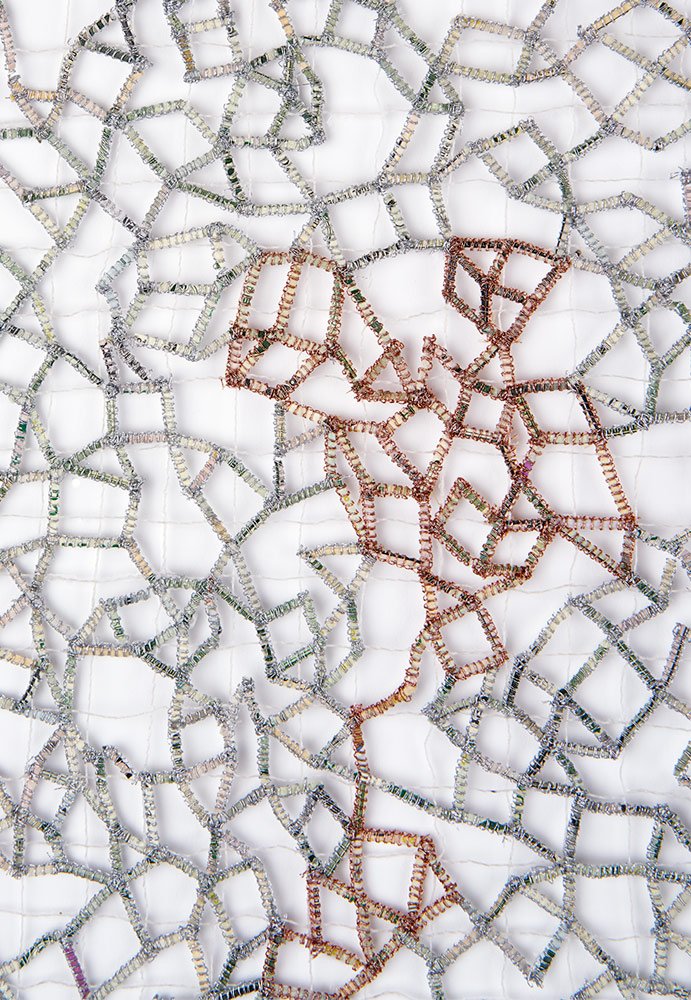

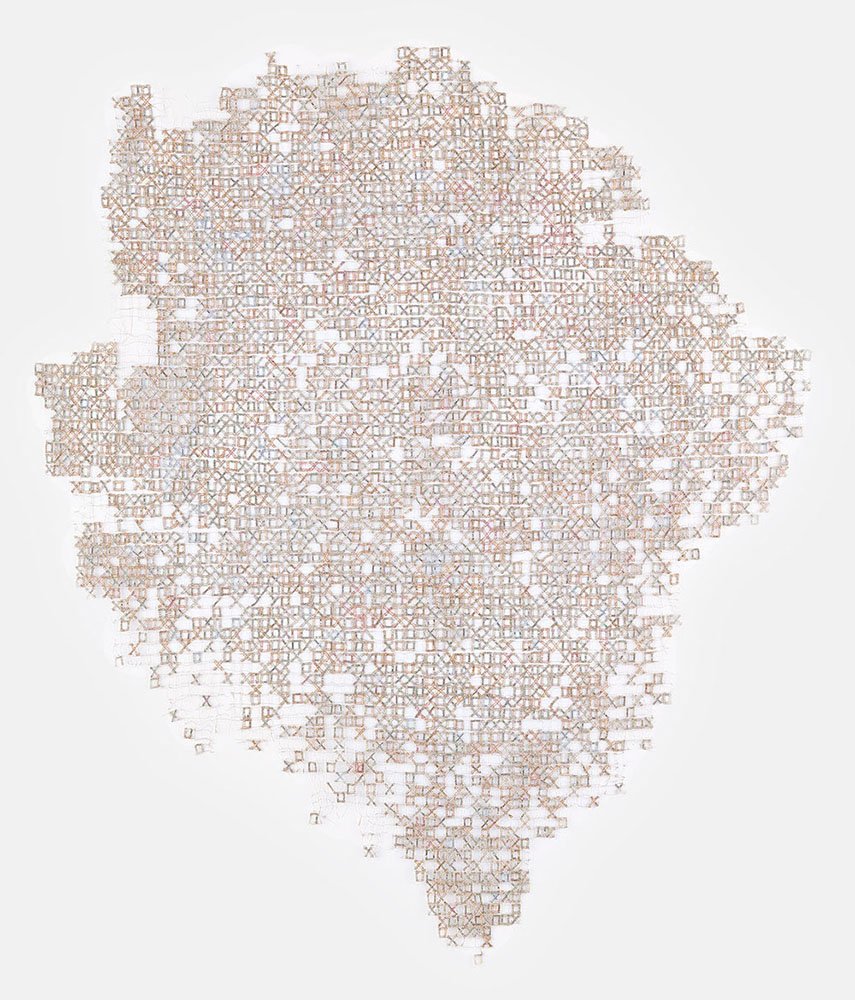

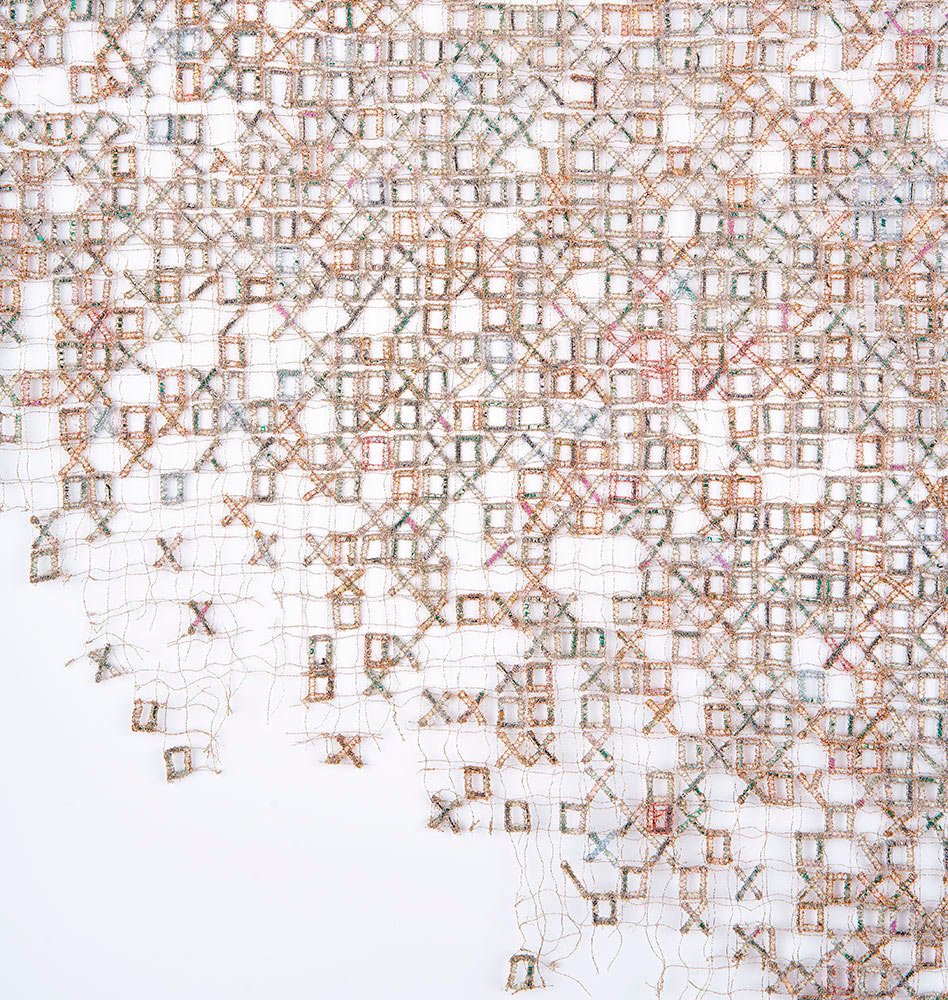

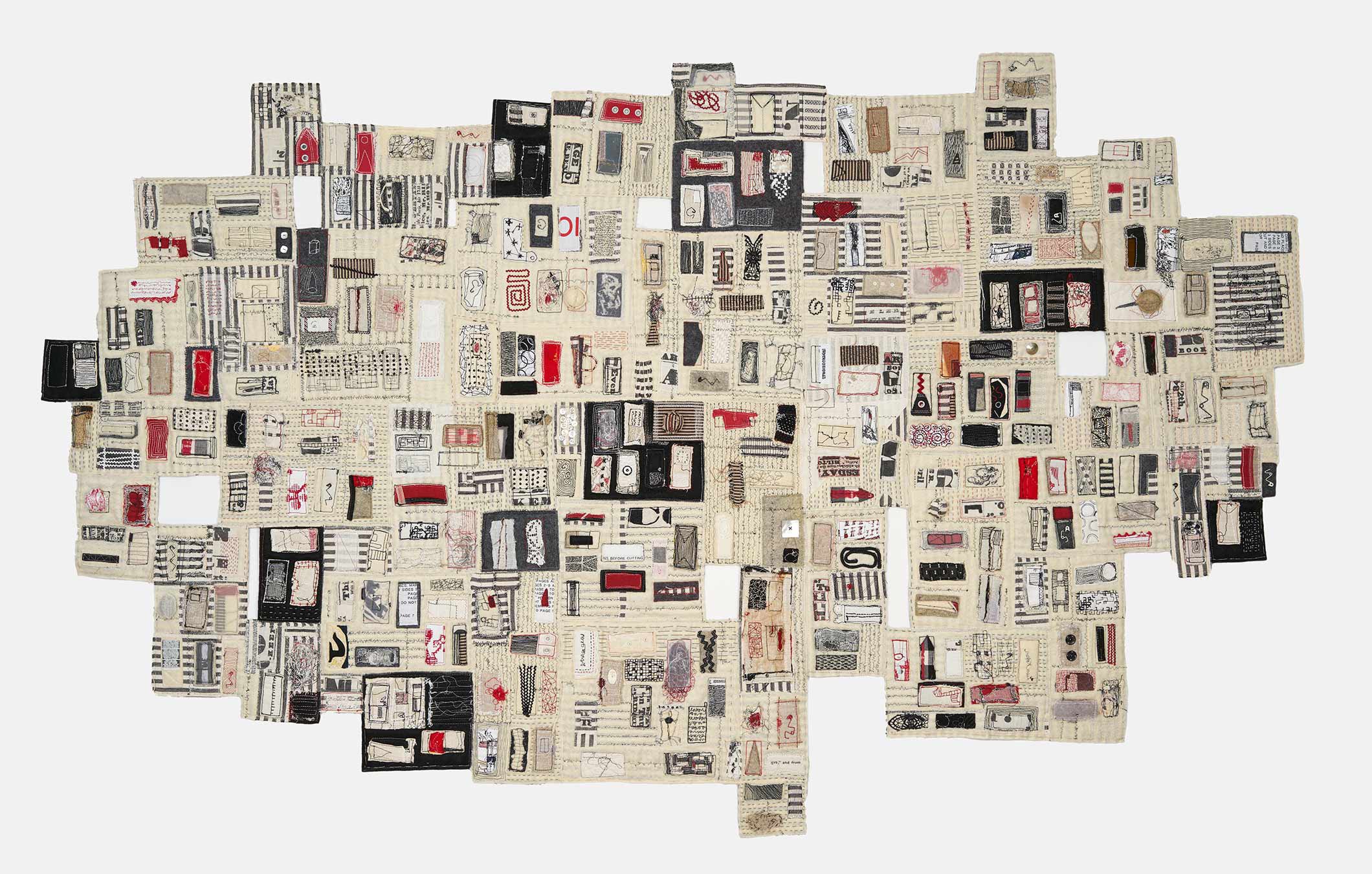

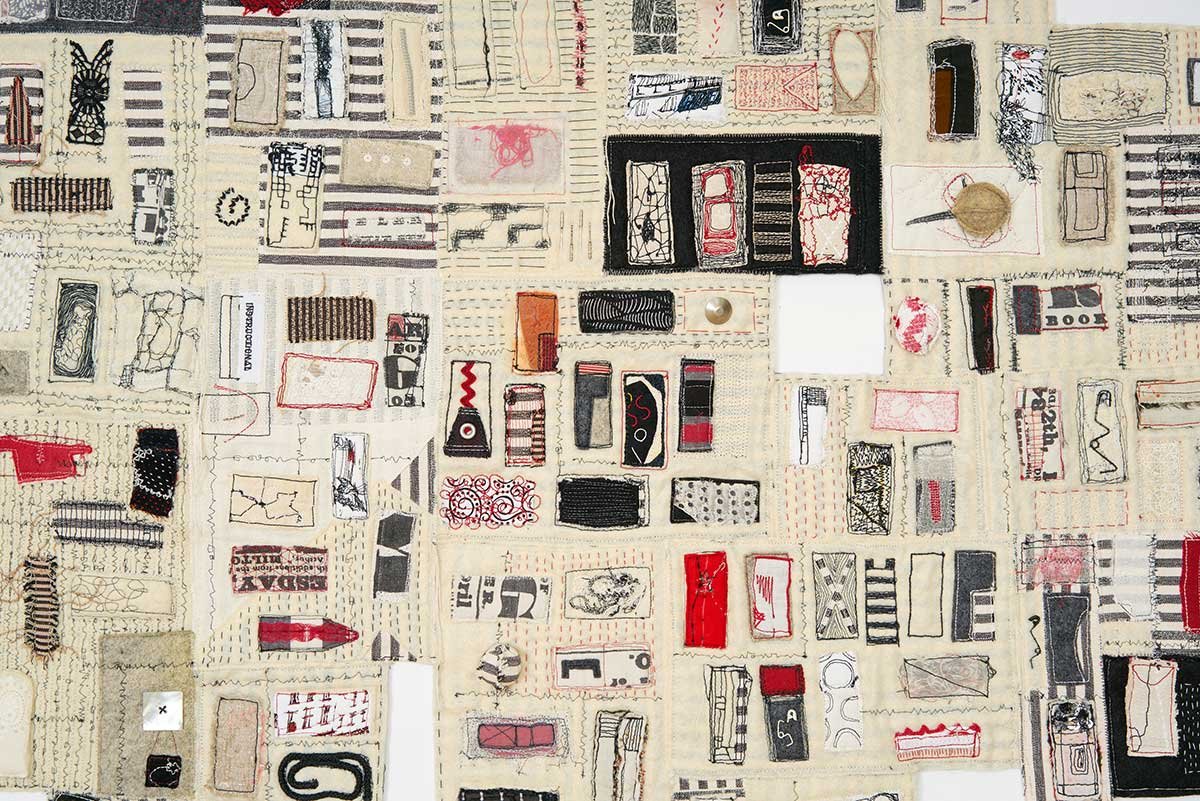

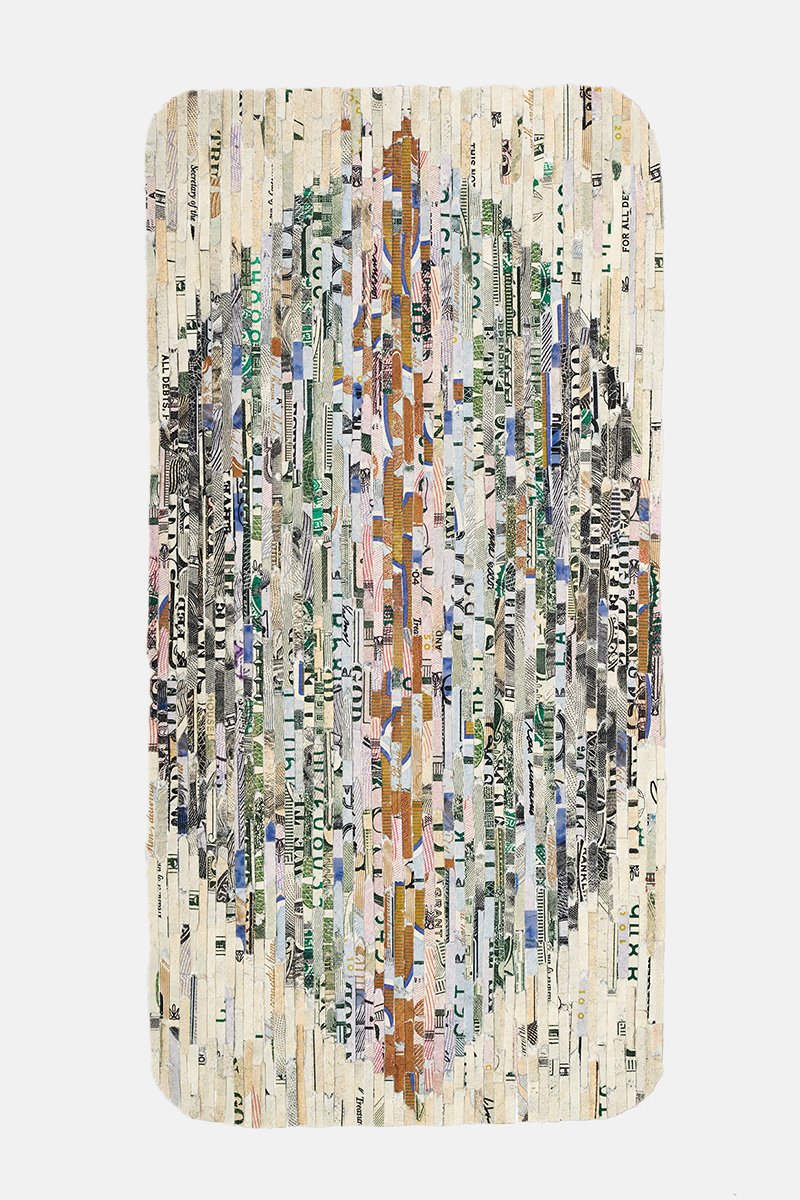

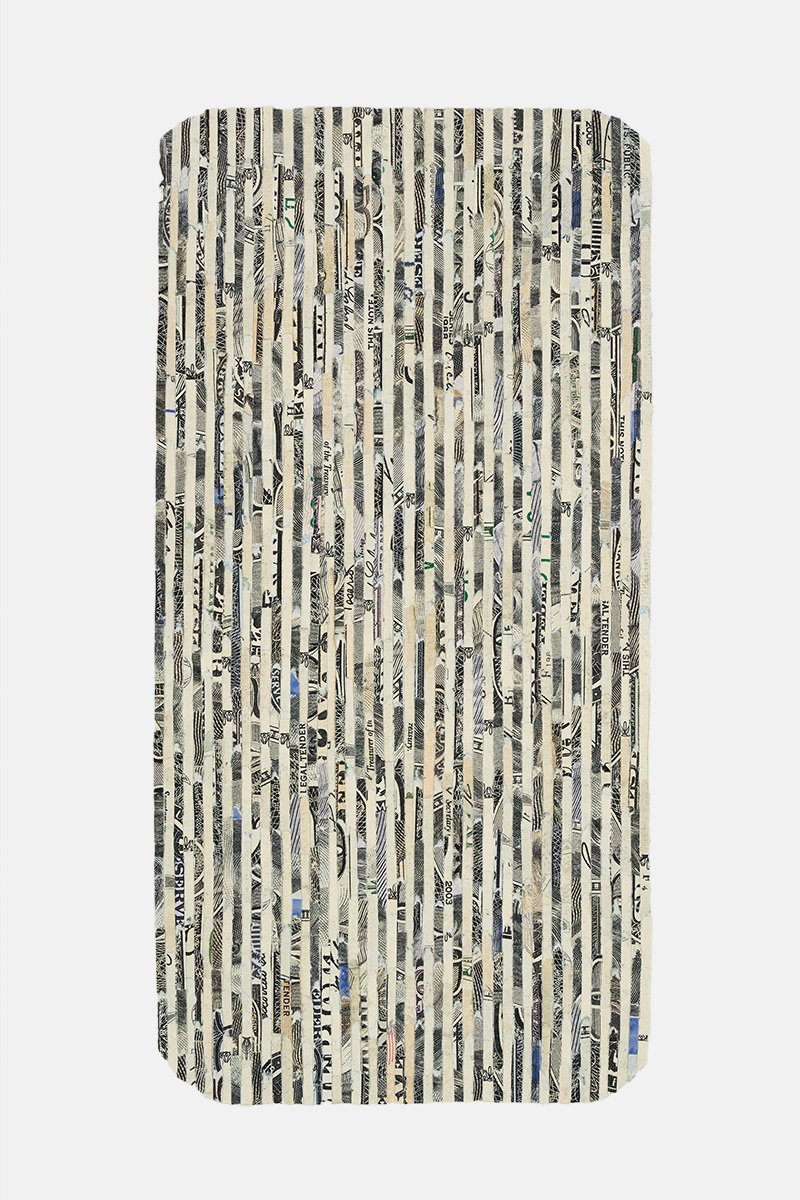

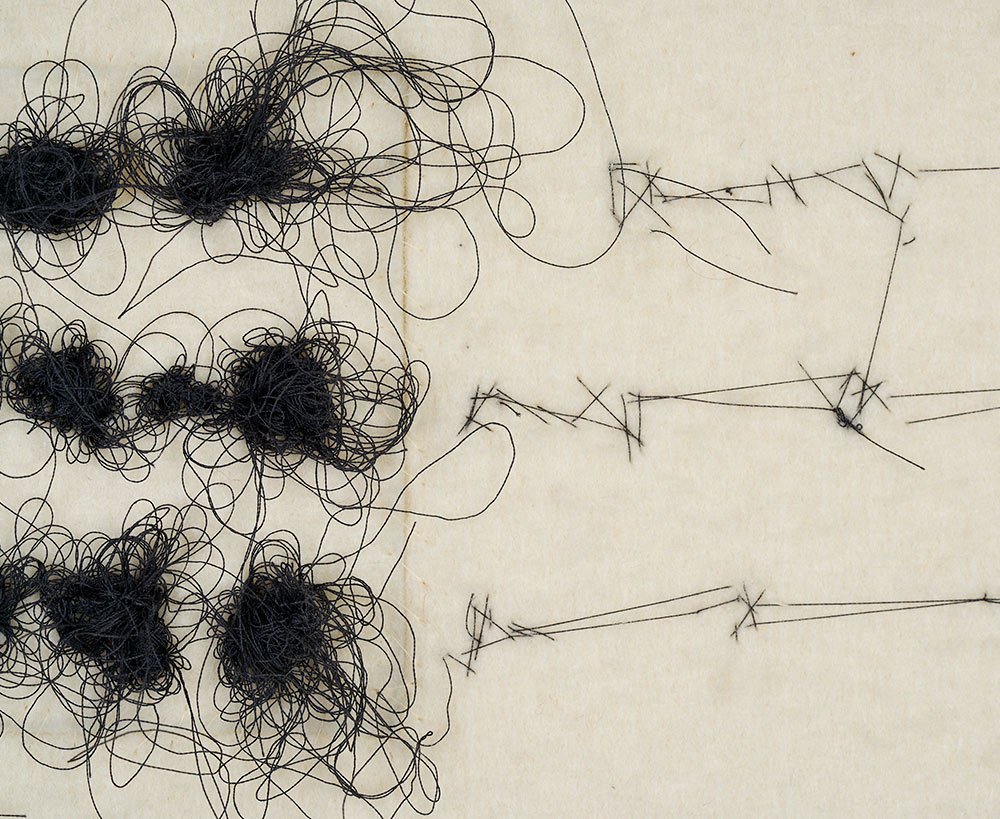

MH: In your process you meticulously cut clothing apart and then sew it back together in monochromatic striations of fabric. What’s the thinking behind your labor-intensive process?

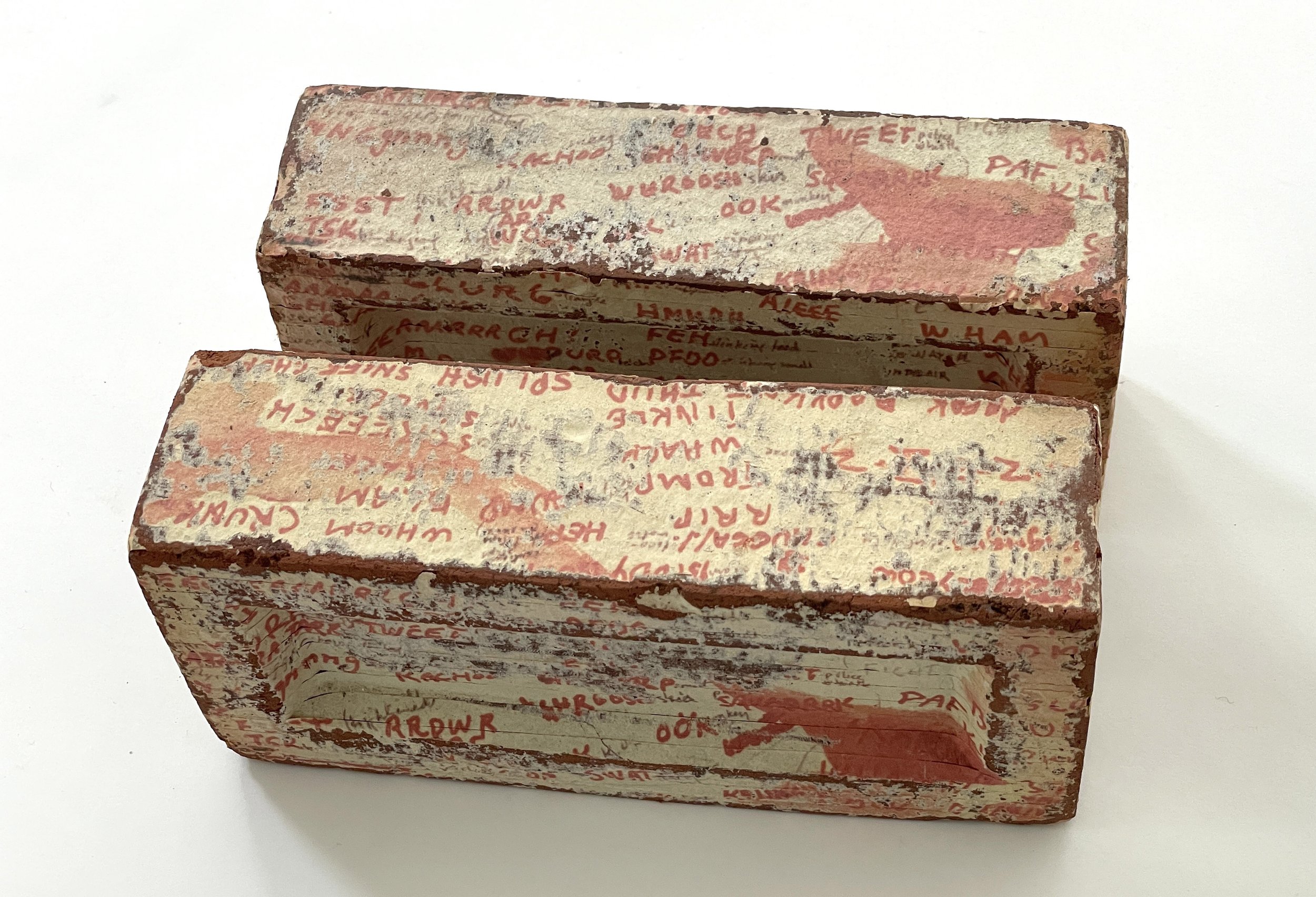

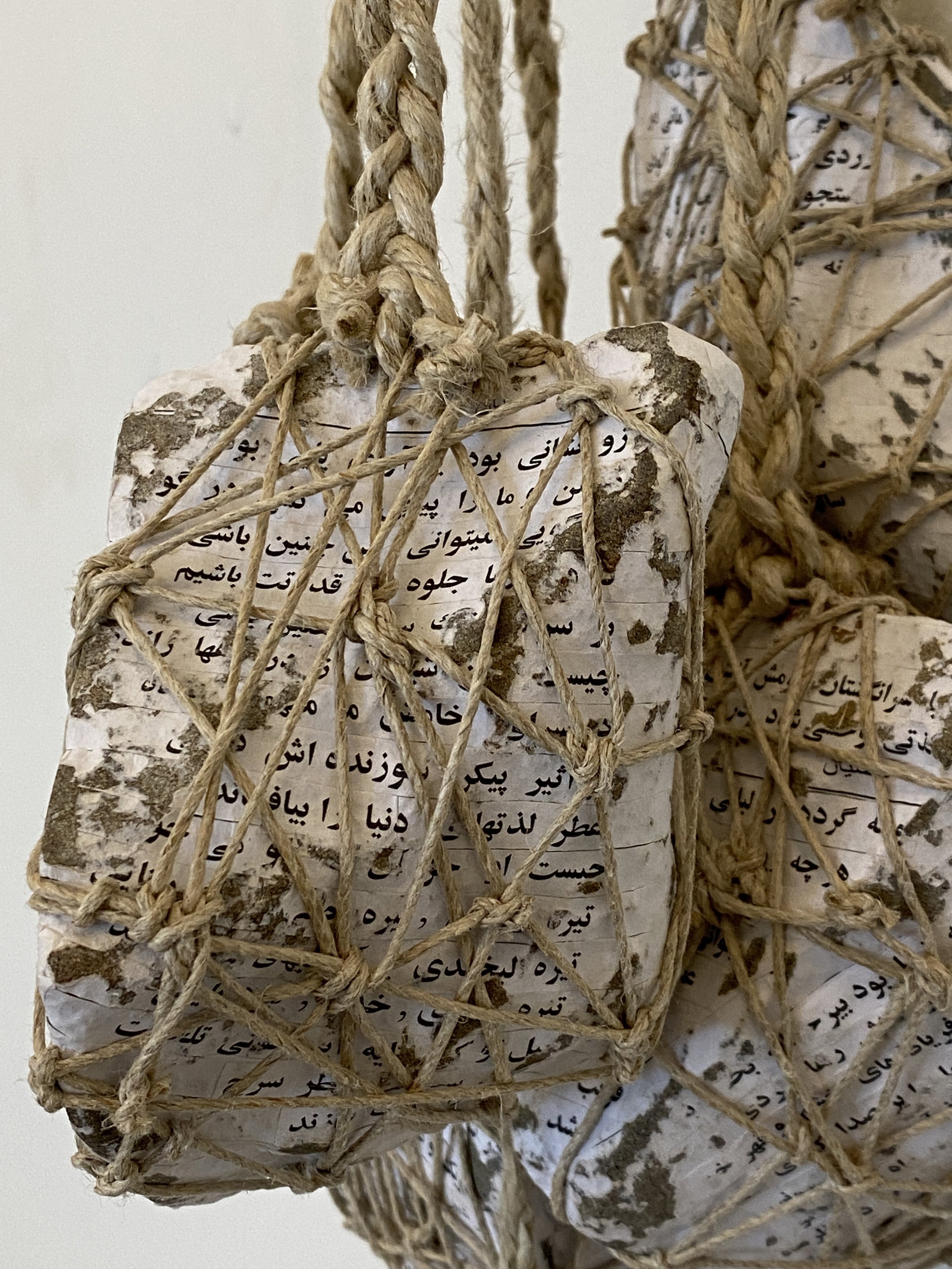

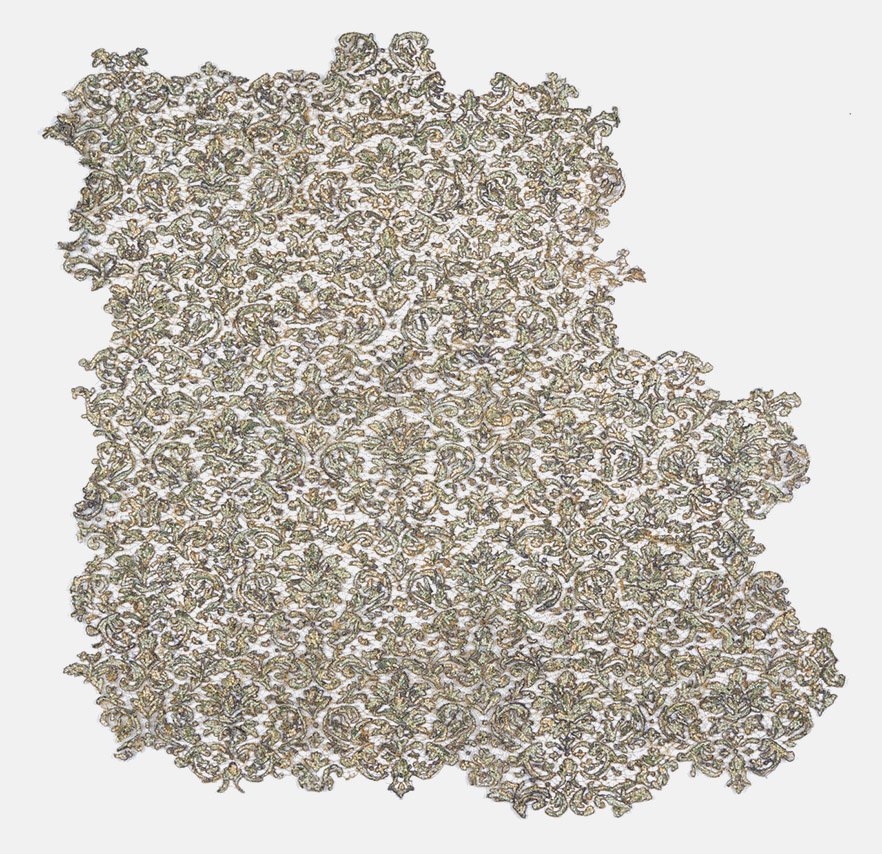

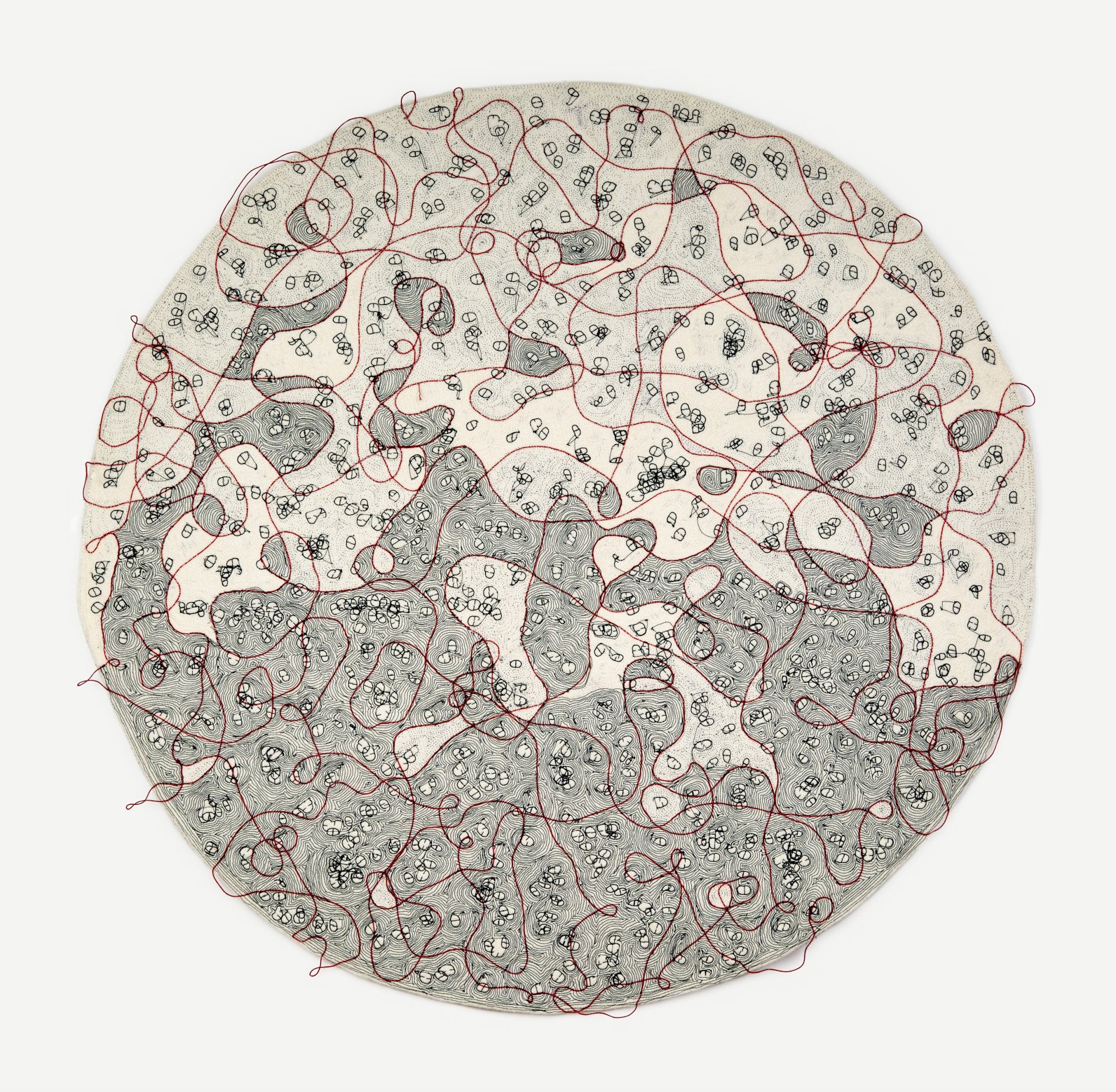

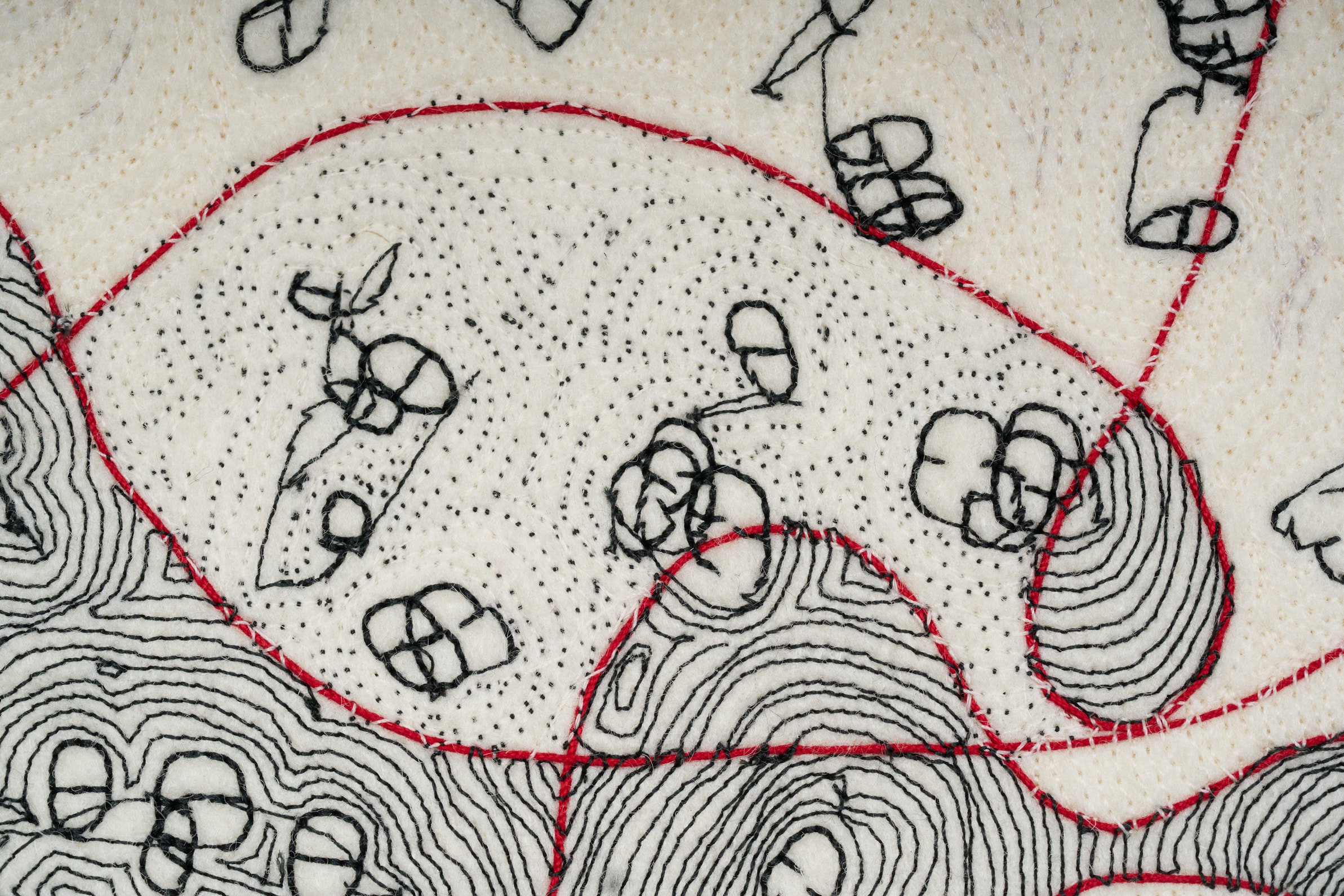

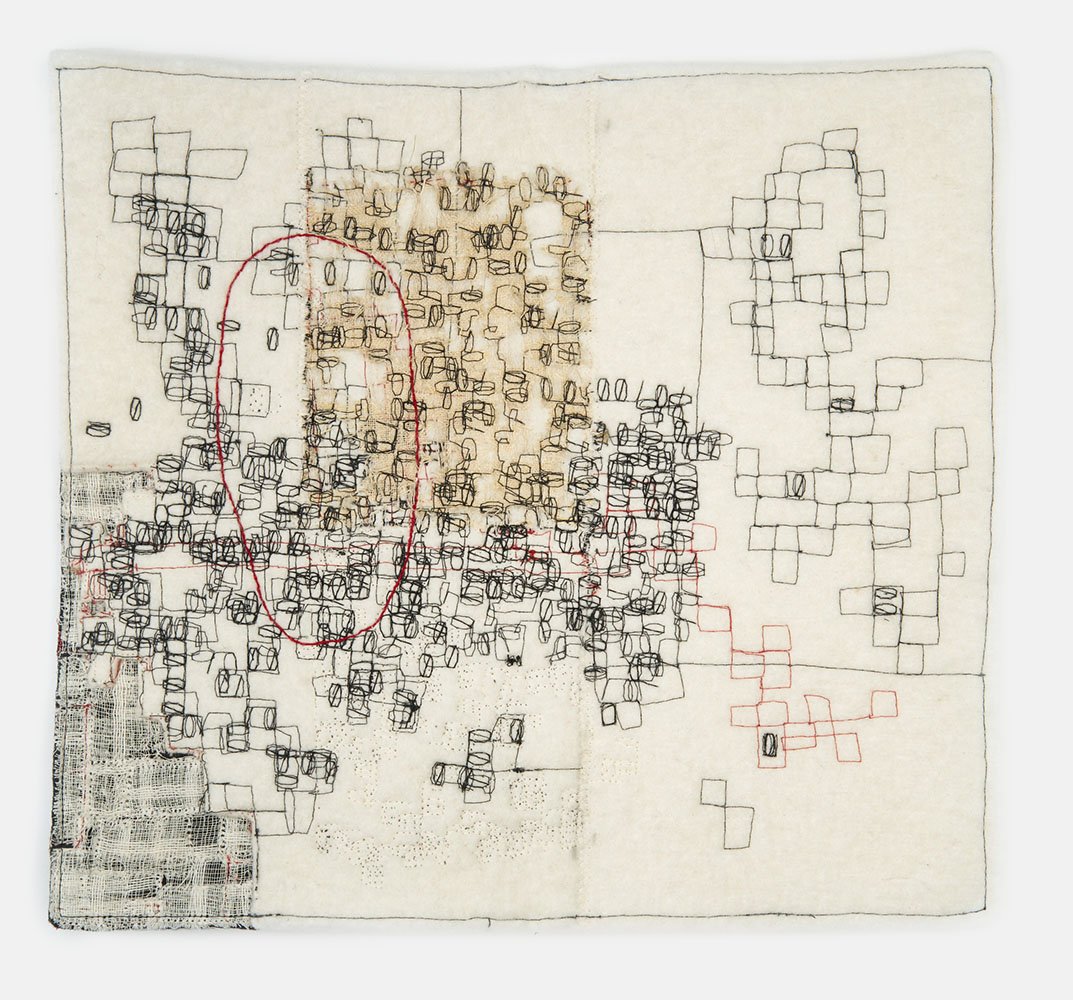

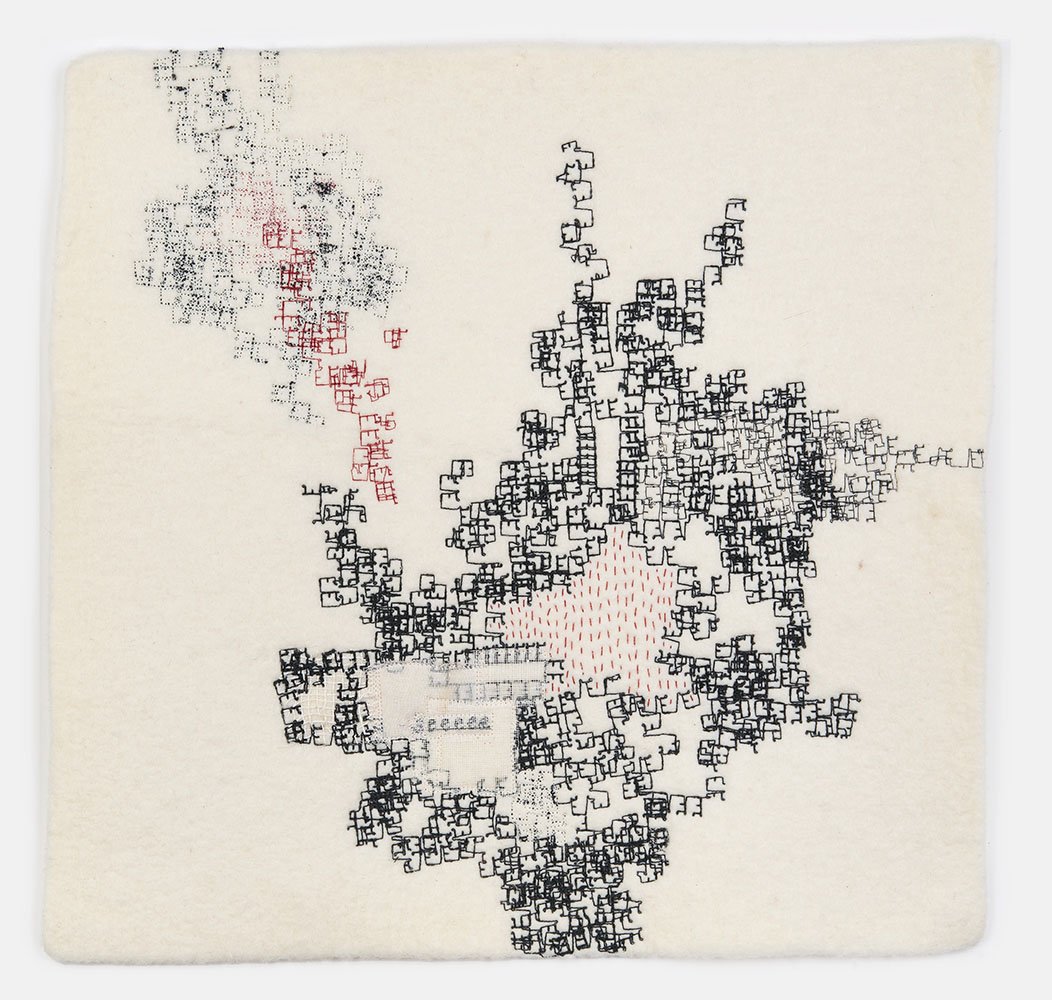

RC: When I moved from California to New York in 2009, I was overwhelmed by the world of fashion and textiles, and I was looking for different ways of manipulating the fabric. I came up with the idea of layering cloth, and I used clothing from my family that I had brought with me from Pakistan. I cut the clothing into long strips, folded them, and sewed the strips together by hand. Around this time, I returned to my family home in Pakistan, only to find that it had been destroyed. It affected me deeply to see that my house that held so many memories did not exist, and there was only wilderness in its place. I thought about all the people who were forced to leave their homes because of war, and how I was able to leave of my own free will. In the villages of Pakistan there are mud houses built with layers of clay and bricks, so I began to think about my layered fabrics in this way. Eventually I ran out of my family’s clothing, so I bought clothes from thrift stores in New York, and I always bought faded textiles because it reminded me of the colors of the architecture in Pakistan.

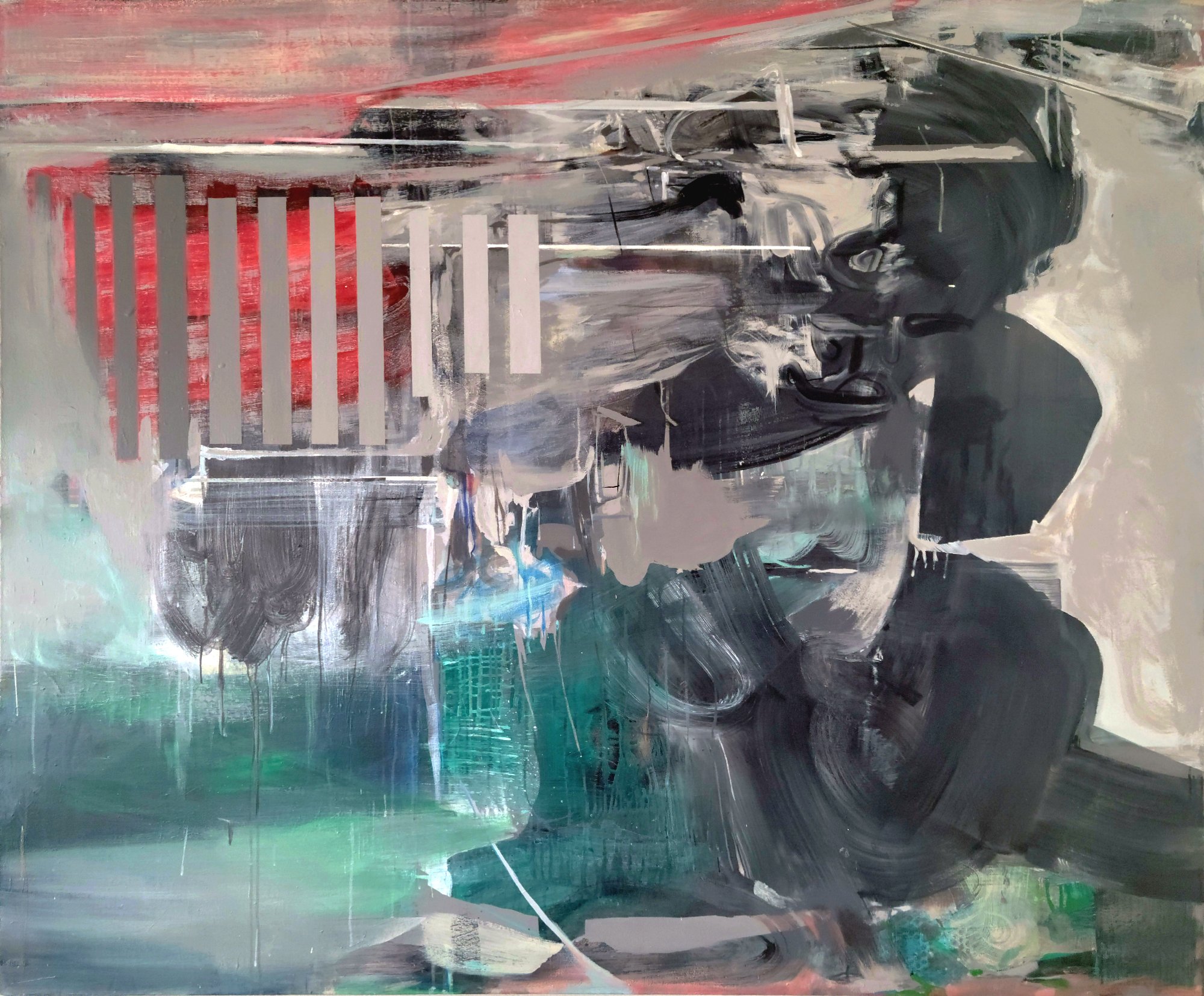

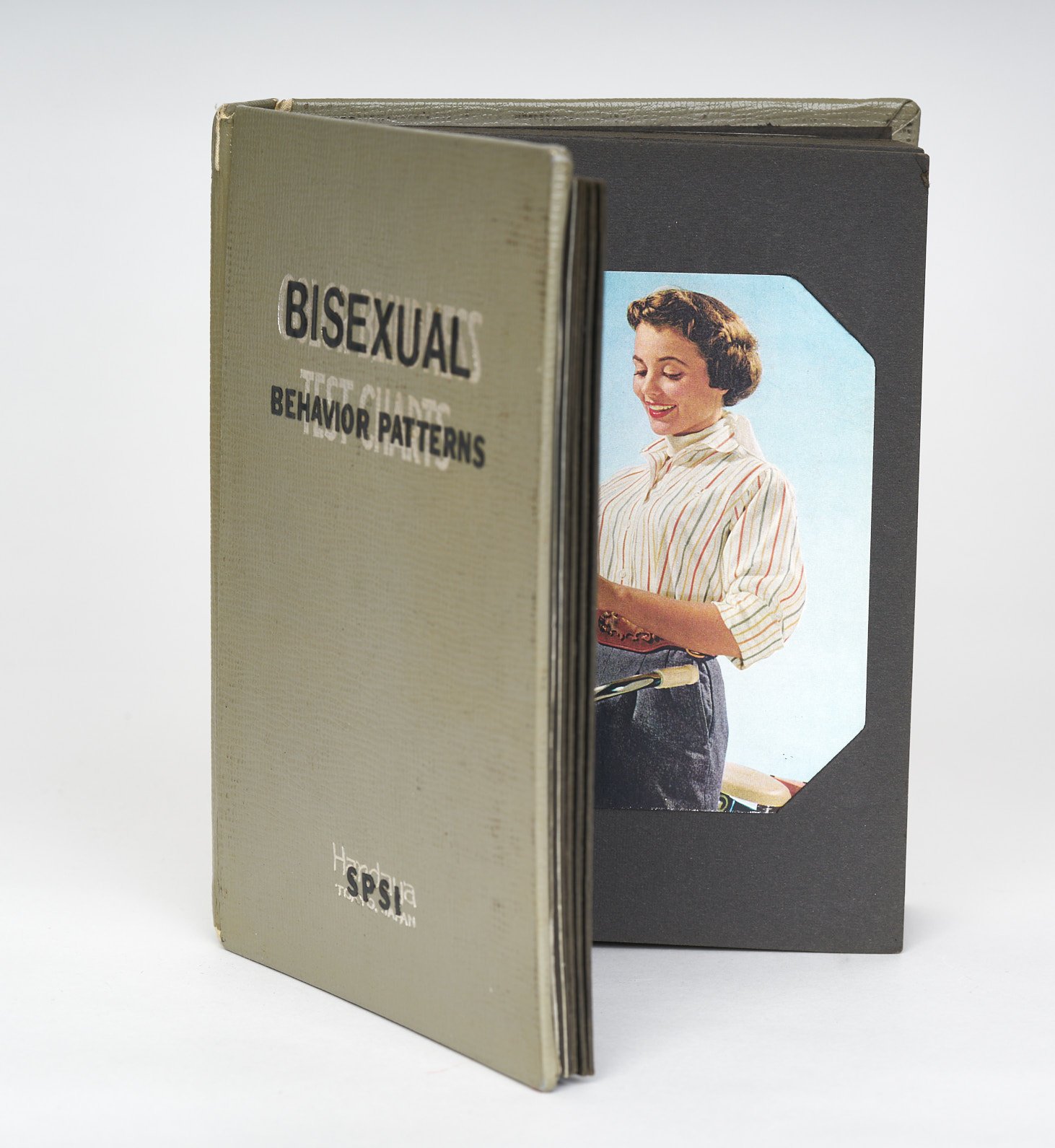

MH: Your work is an exploration of the body – usually female – using architectural, often masculine forms. It’s an interesting dialogue between the feminine and masculine, and I understand that your personal history plays into these choices. Would you talk about that?

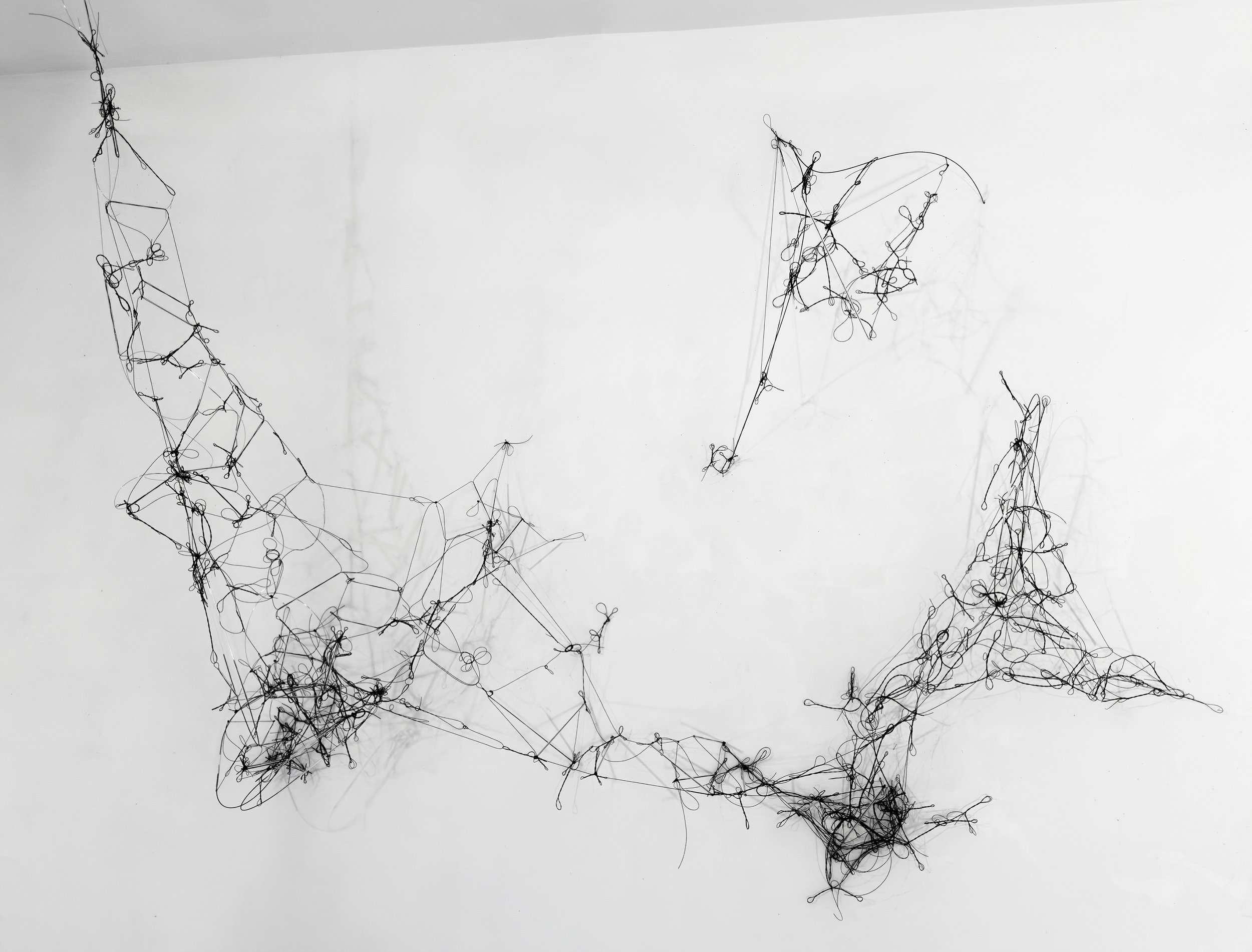

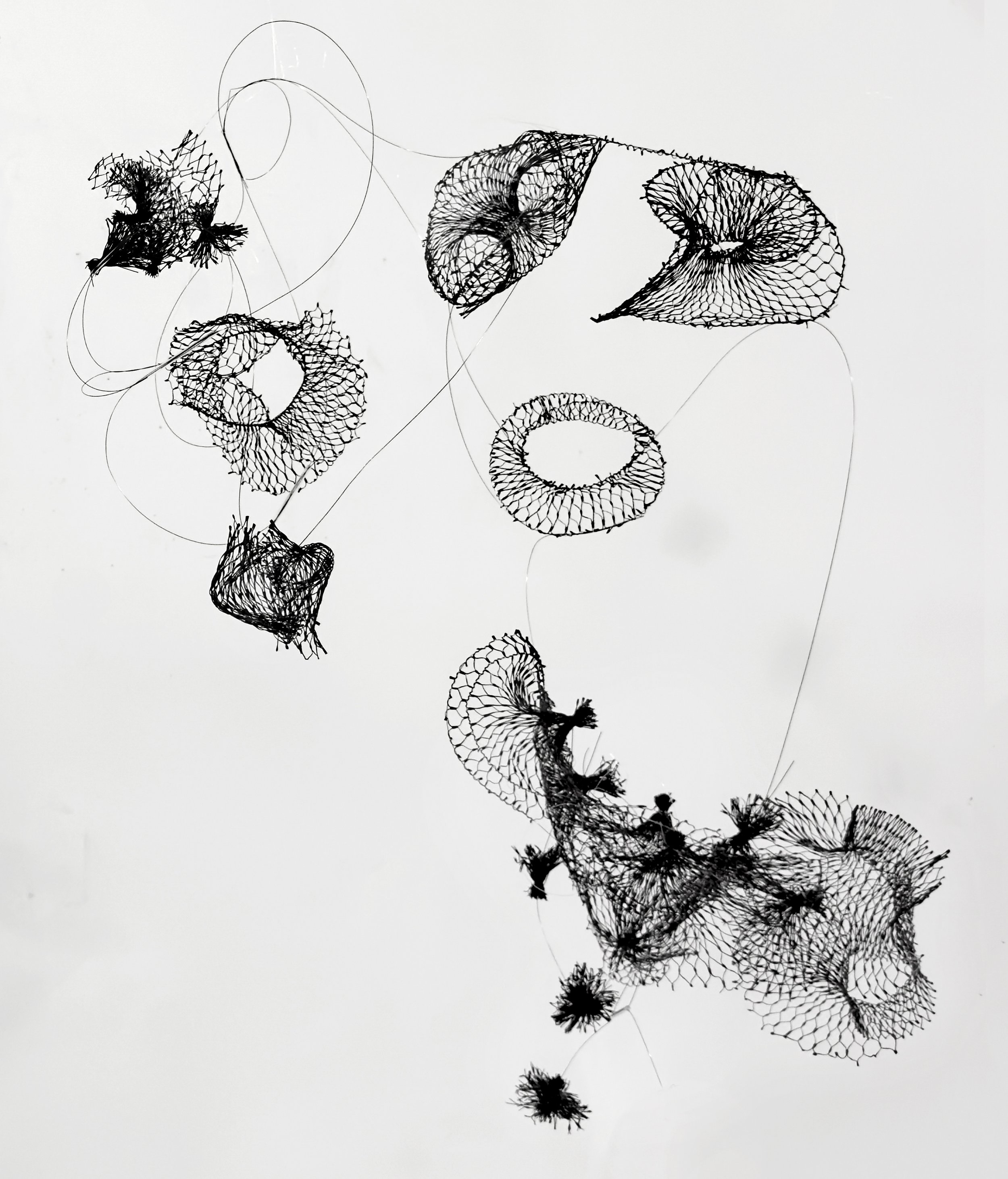

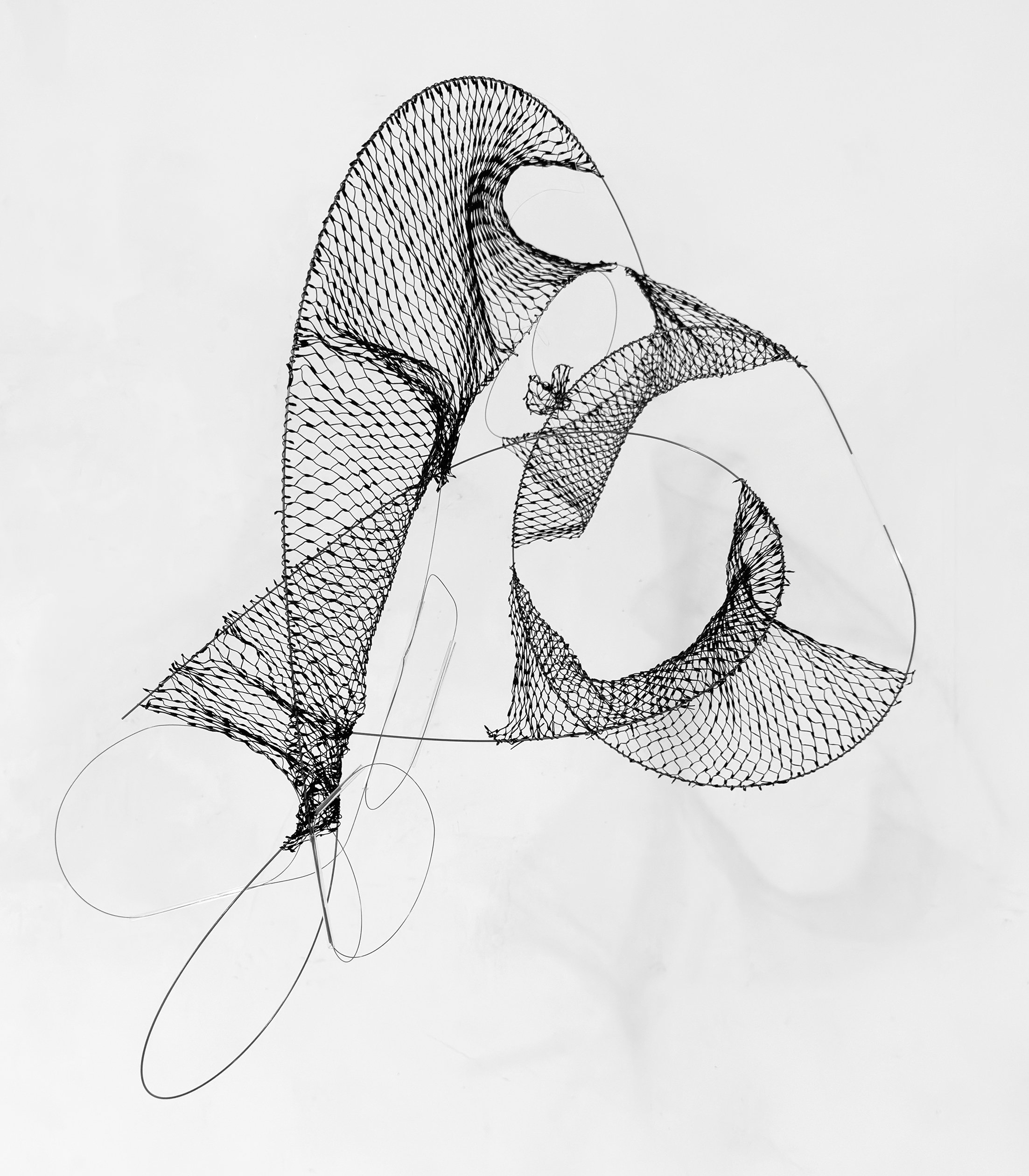

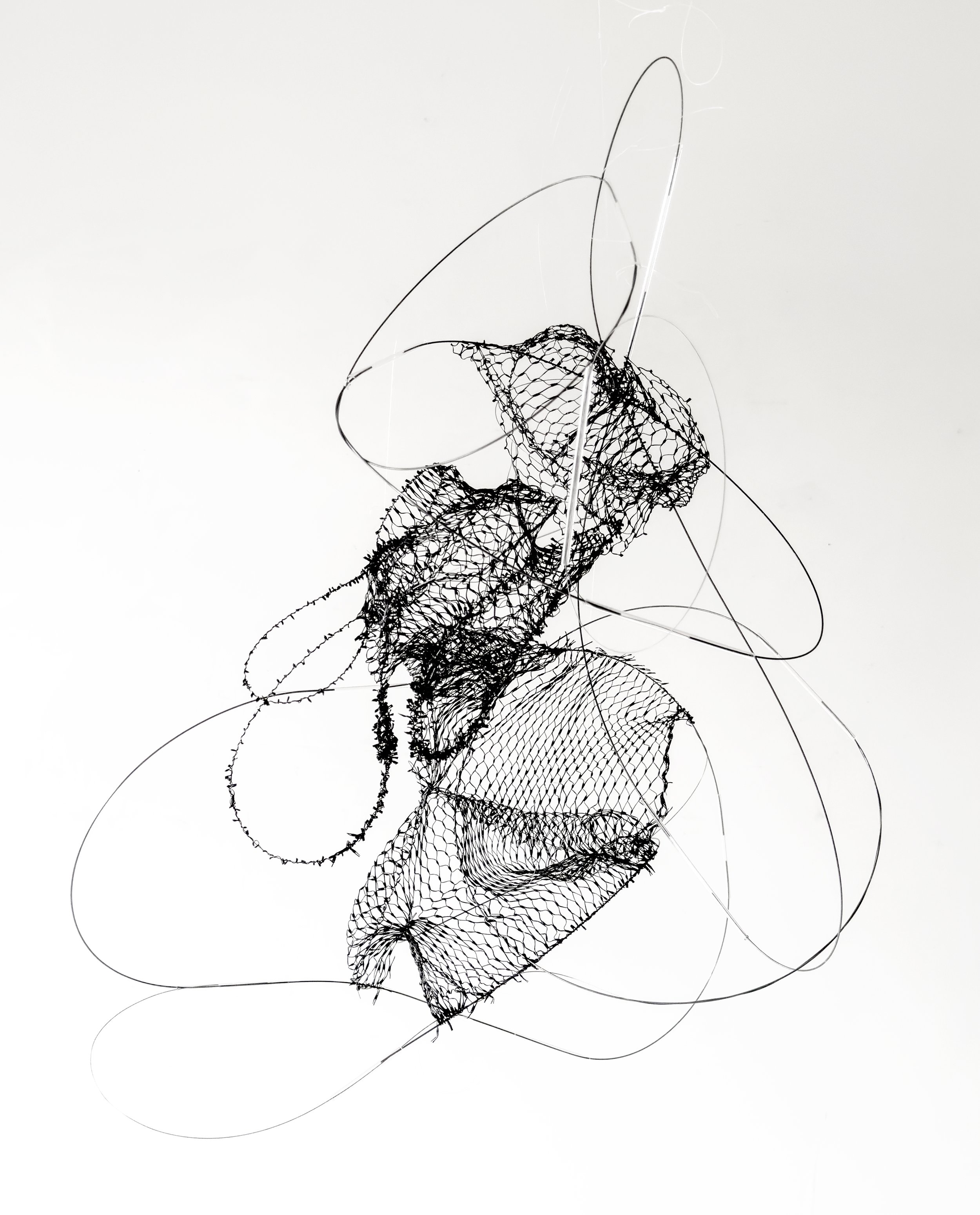

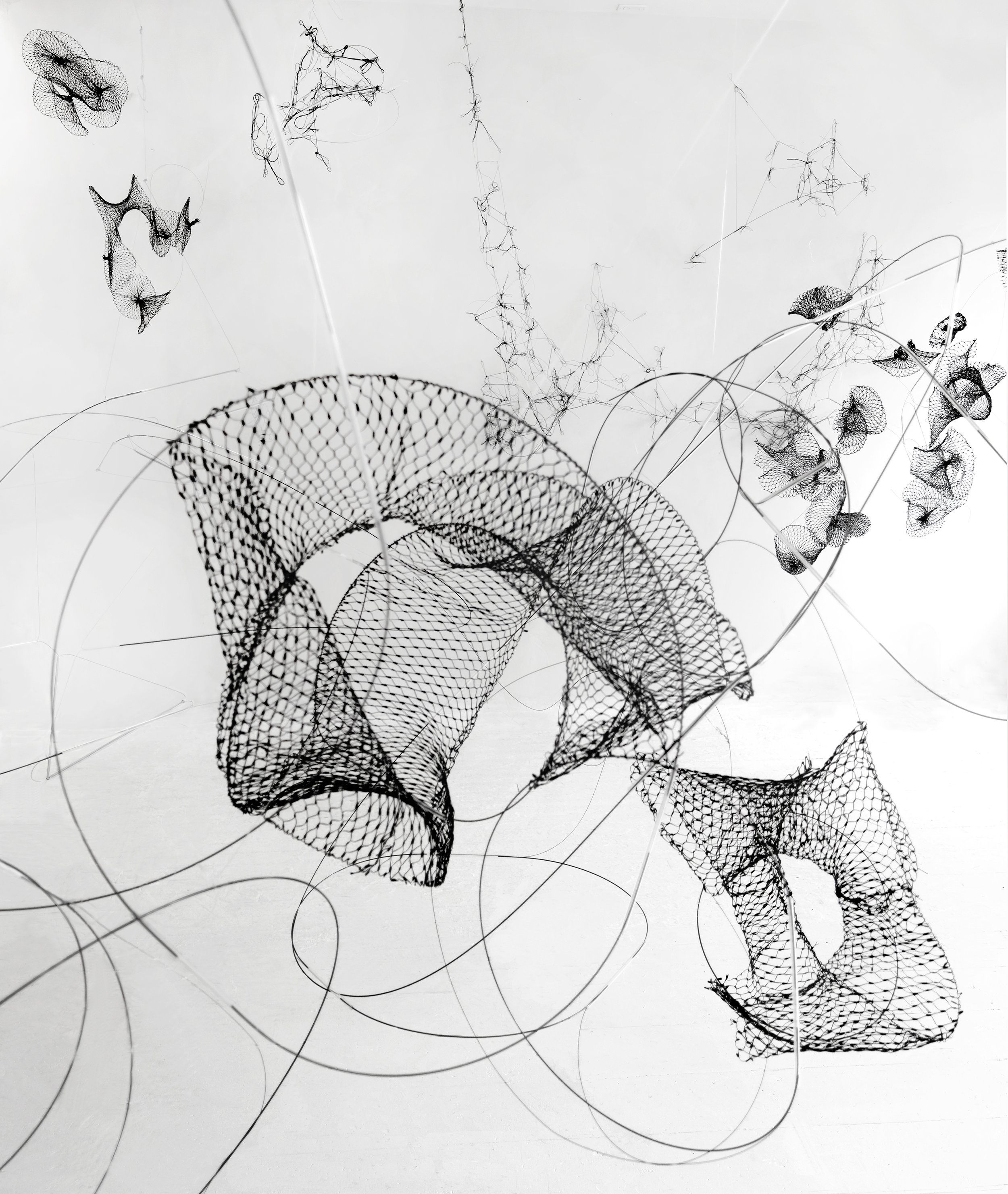

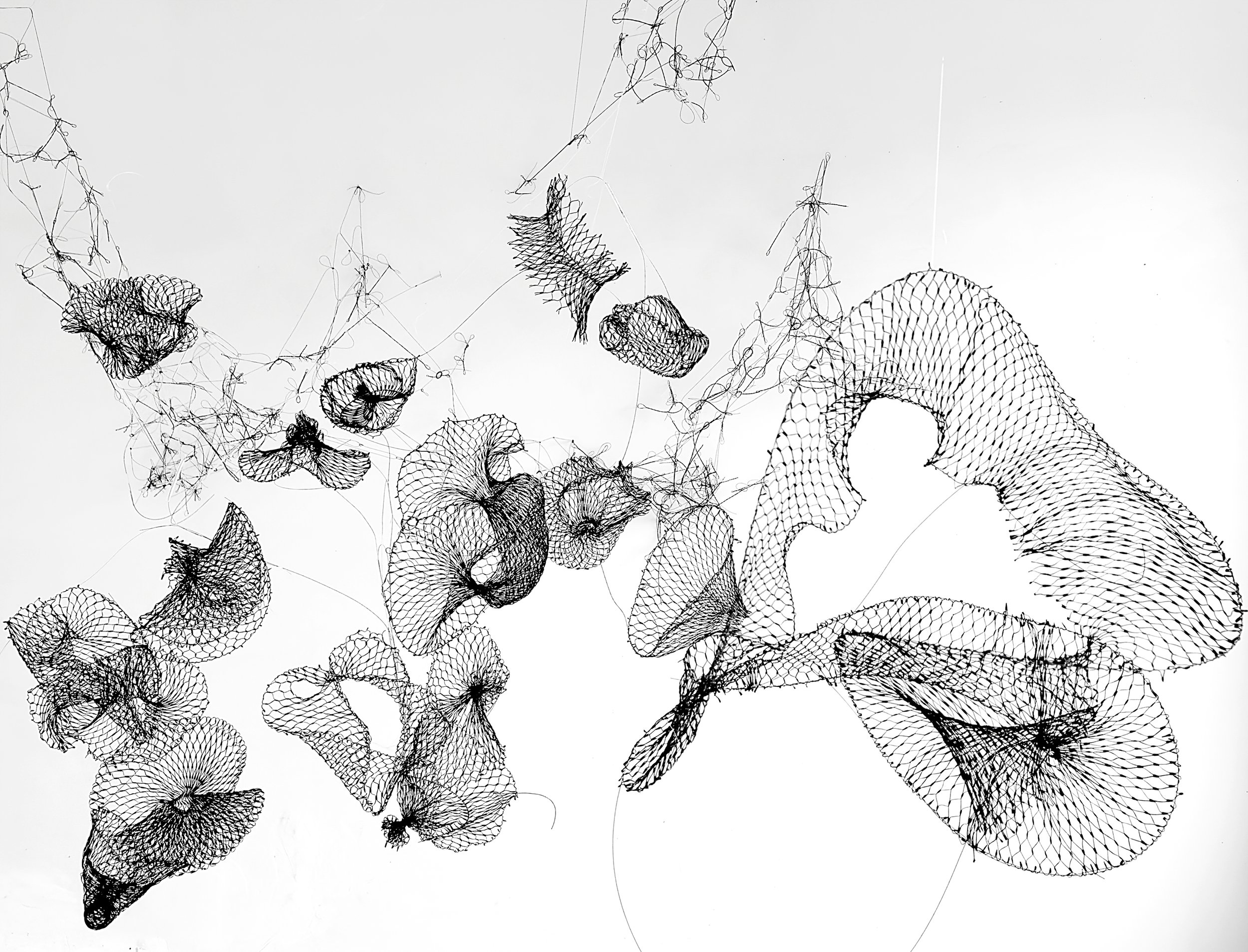

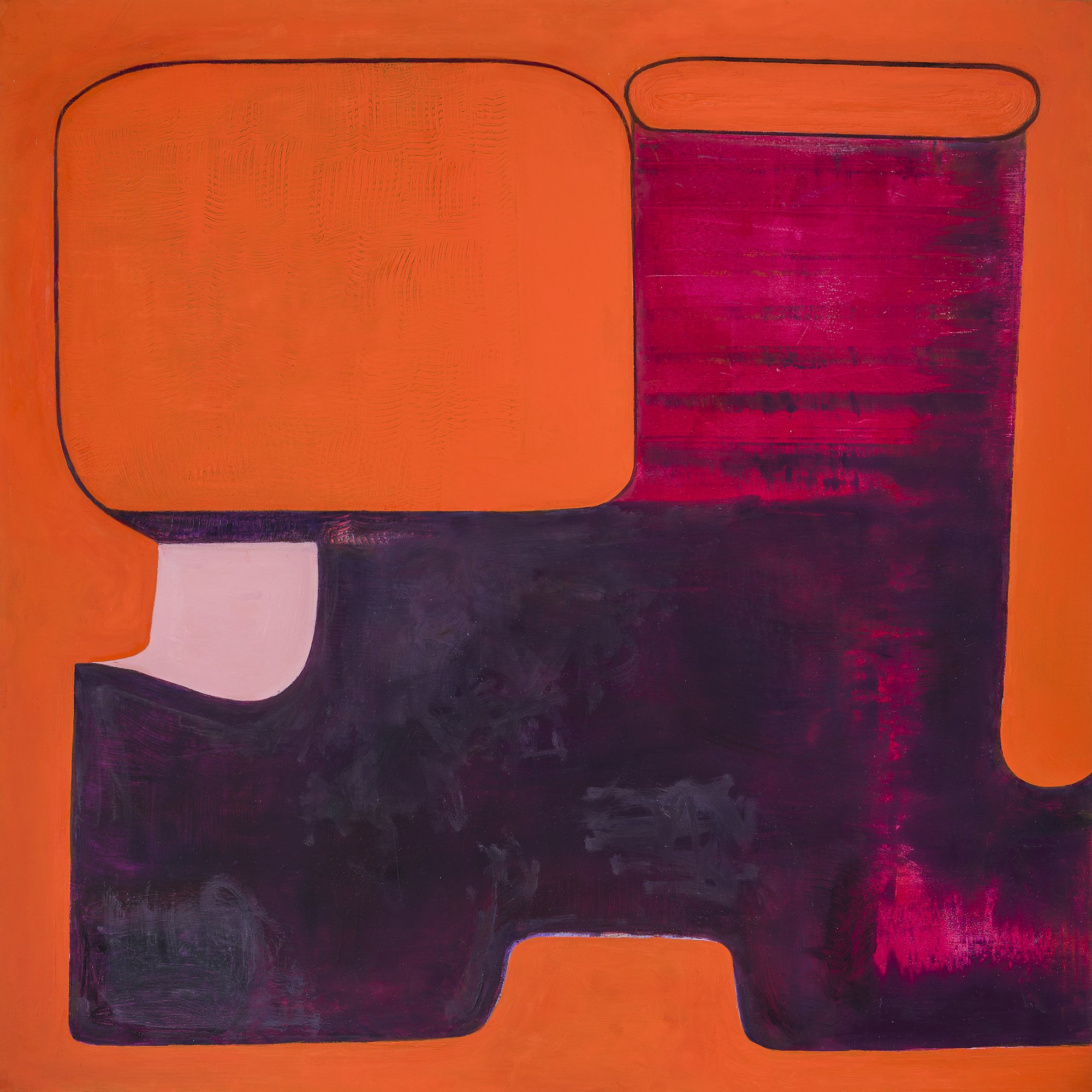

RC: I find architecture and the body to be similar because both occupy space. In architecture people live and leave, but memories live in the body. So I was thinking about how to express this, and I made a dress that was like an architectural structure. I constructed it with wire mesh, then I removed the wire so I could wear it. I wore the dress during an art fair in 2013, standing on different intersections in Dumbo as a way of integrating my body with the architecture of New York City. It expressed some of the anguish I felt over the home that I left behind in Pakistan.

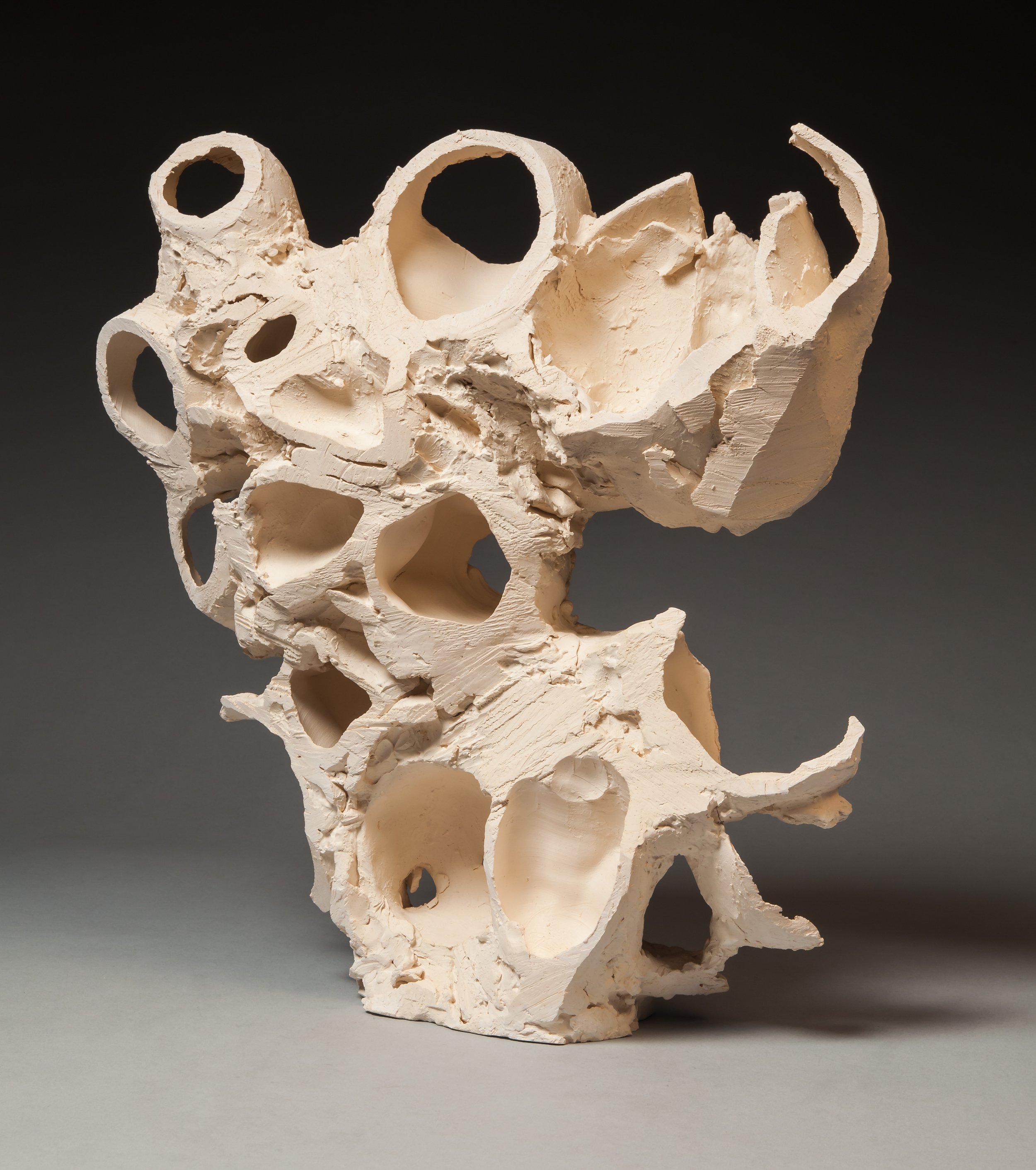

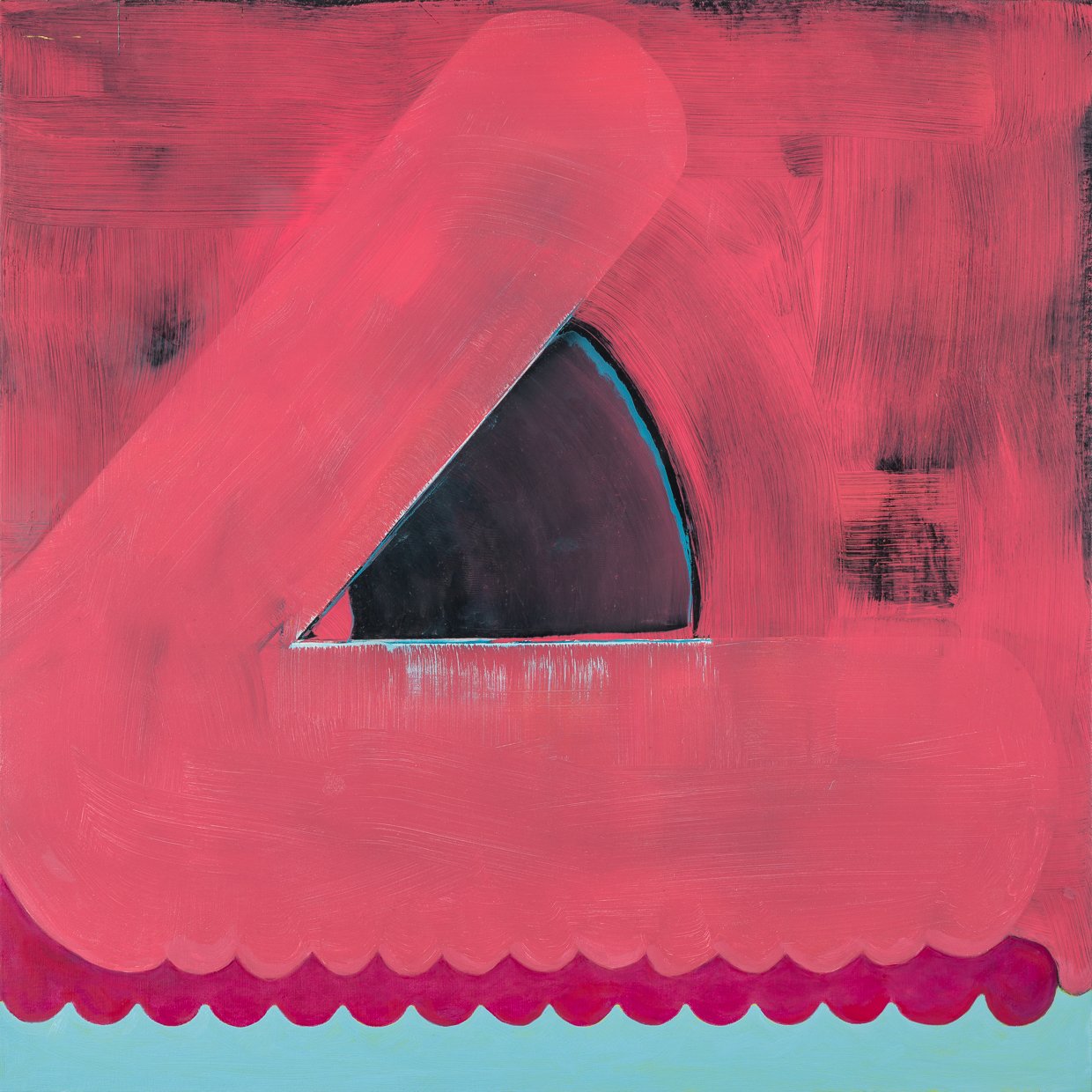

MH: Windows are prominent in your architectural forms. I feel like I’m looking into a doll’s house, but one that was vacated long ago. What significance do windows have for you?

RC: Windows are a very specific part of architecture, and whenever you see a demolished building, somehow the structure of the windows is still hanging from it. For me windows represent the desire for other life forms to come in, so I put lots of them in my pieces, most of them open.

MH: All your forms, no matter the size, have a monumental feeling. It’s like your work is larger than life, both figuratively and literally. There’s also a weight to them, a gravity in both senses of the word. Would you comment on that?

RC: I’m not aware of the monumentality, but maybe since I reference architecture so often, this gives it that larger than life feeling. I also think that making a piece of clothing that’s larger than myself has a psychological impact, because we all share the desire to be bigger than we are. And because our associations with clothes and the body are different from other objects, they have greater impact.

MH: I’m thinking of the oversized men’s overcoat that I saw a few years ago at Hudson Valley MoCA. It was a remarkable piece and had a huge impact because of its size and bulk.

RC: That piece was related to issues that I was dealing with at the time, having to do with my desire to be loved and protected by a God-like father figure. I bought a men’s wool coat from the 1940s, cut it apart, and enlarged it by adding fabric. The coat was over 8 feet in height, and added various things to it, including a small tricycle.

MH: You mentioned that you were a fourth daughter, and I had to think about that for a minute before I got it. Giving birth to a fourth daughter in Pakistan is probably not occasion for great celebration. Do you think this position in your family contributed to your becoming an artist? More importantly, did it fuel your exploration of the feminine?

RC: This is a key question. There was an older brother, then 4 daughters, then when my younger brother was born it was a big event in the family. My grandmother told everyone that God had answered her prayers and given her a pair of sons. It’s such a cruel society, and you feel it every day as a girl. But it gave me some freedom because no one paid any attention to me, so I could climb trees and be a tomboy and no one cared. All my life I’ve struggled with this issue, trying to prove that I’m not lesser than anyone.

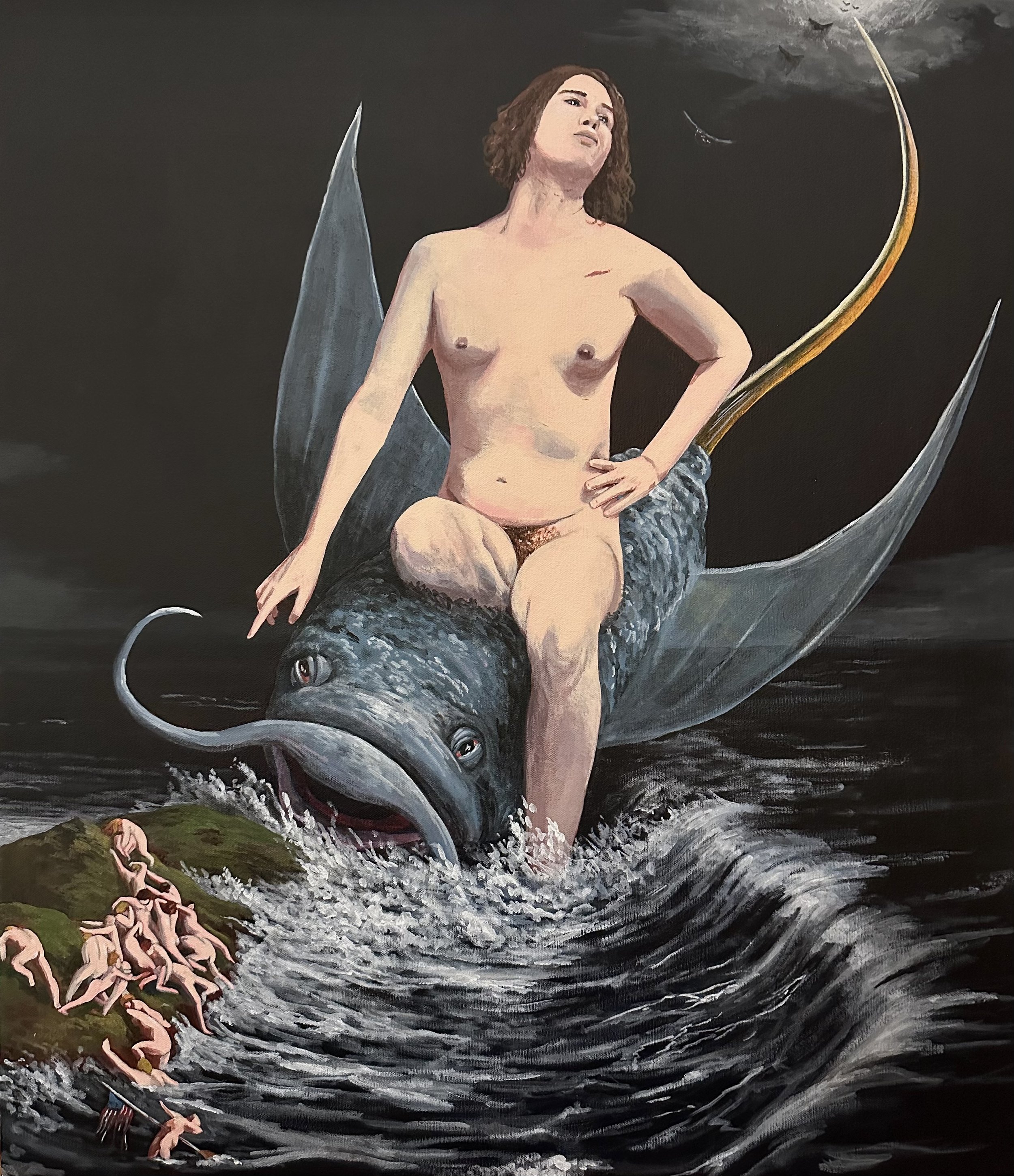

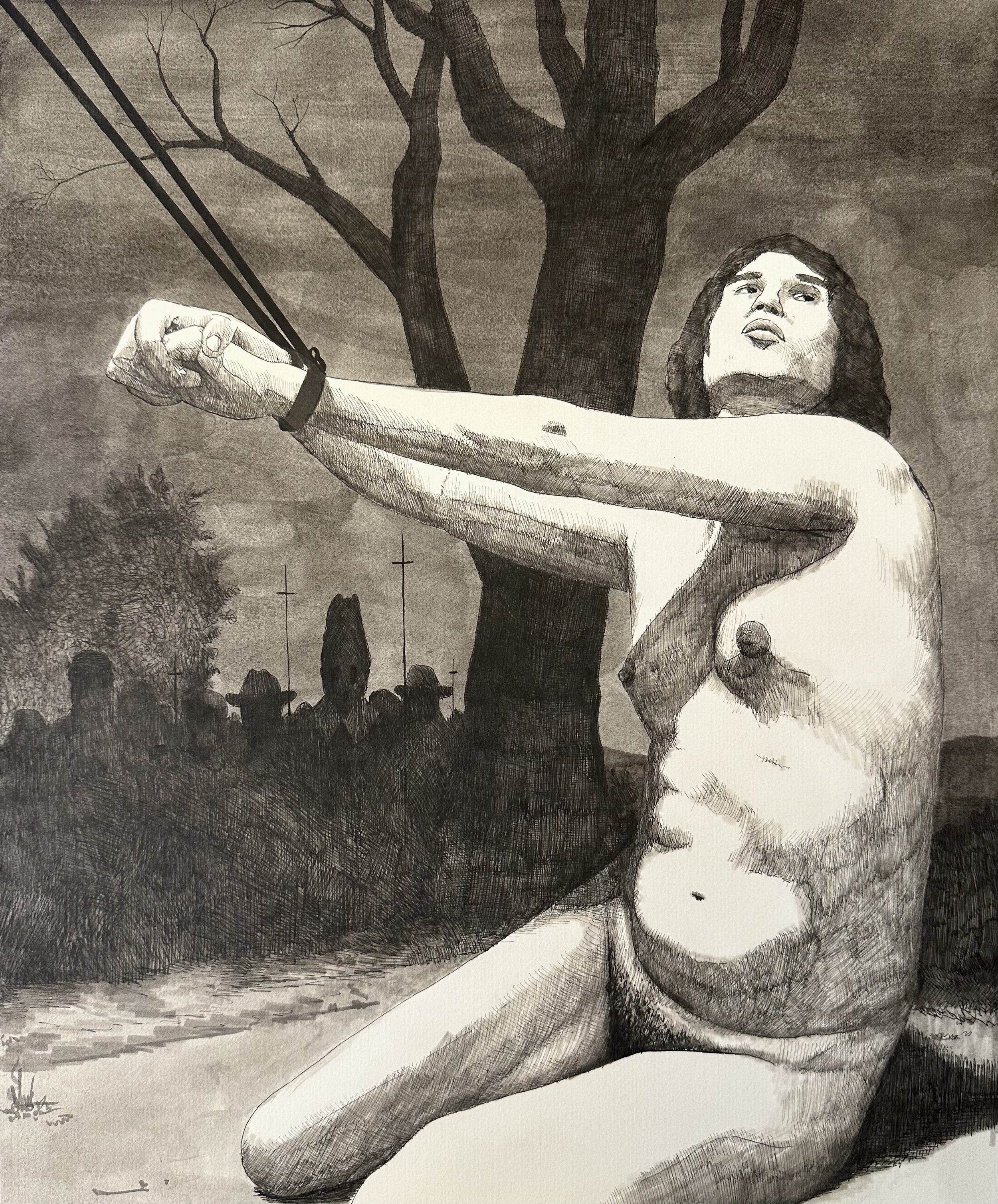

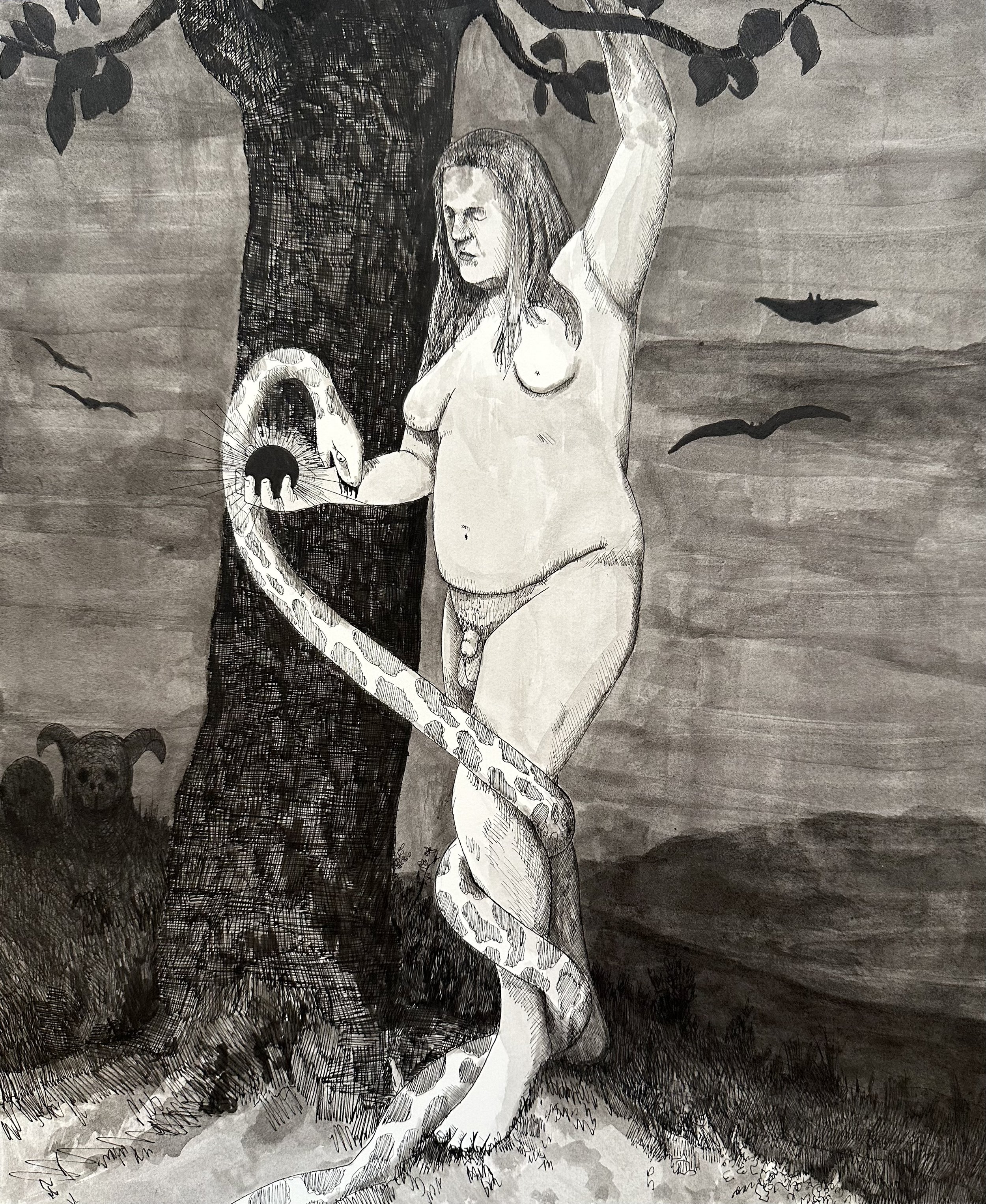

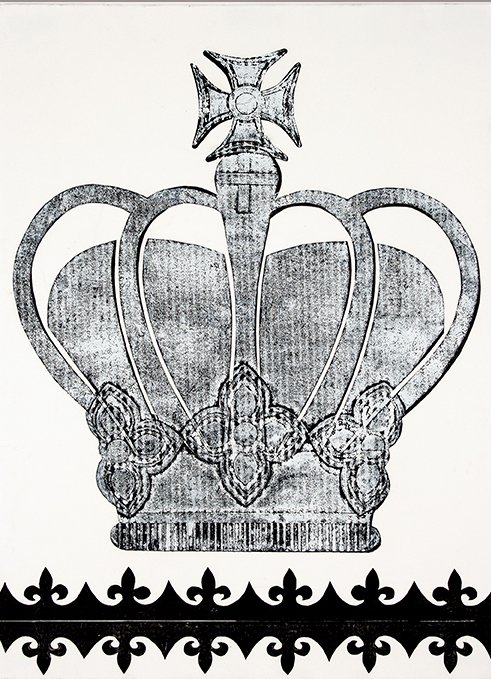

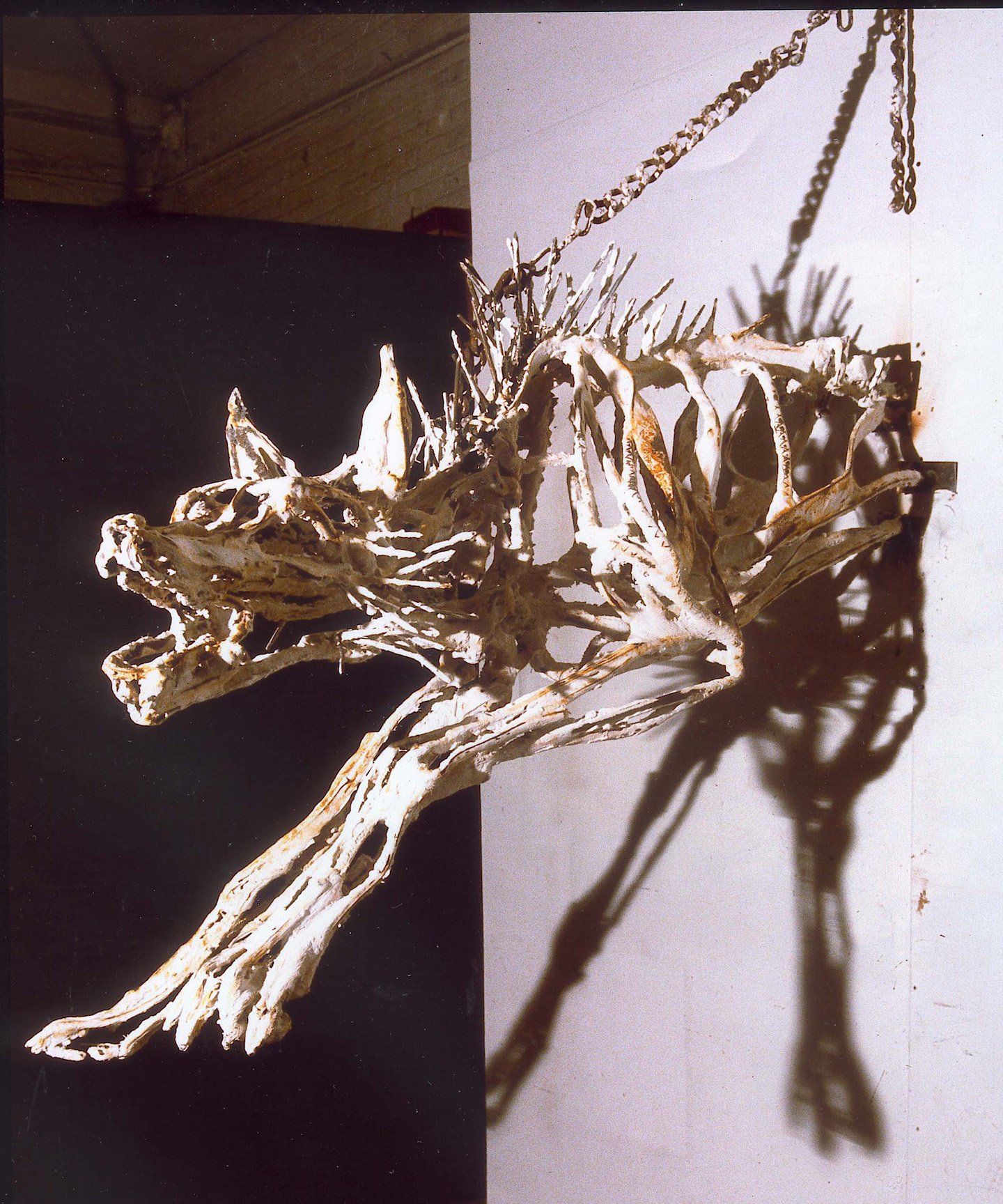

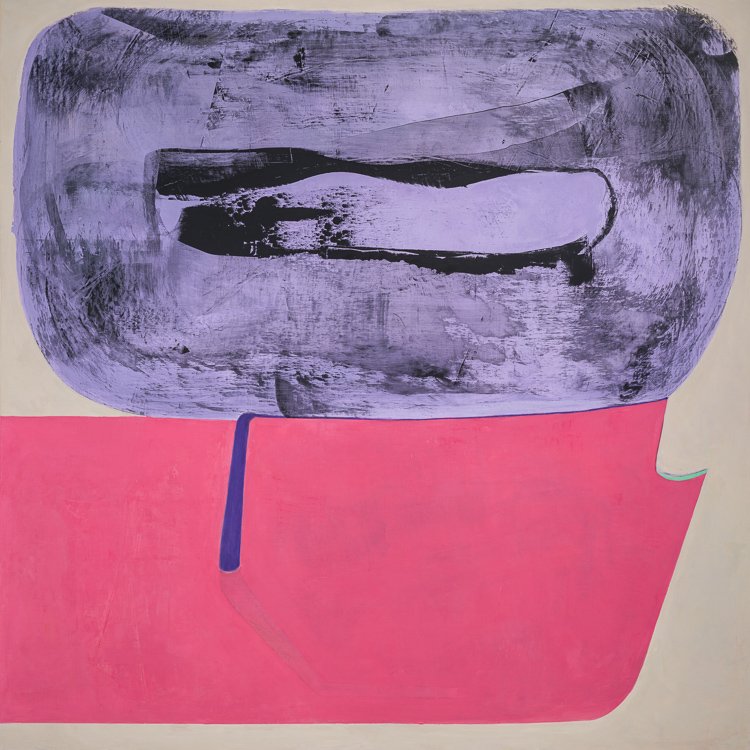

MH: And yet you’ve become an artist who creates images of empowered women. Your women are helmeted warriors! They’re regal, fleshy, fully confident beings. How did you evolve from fourth daughter to these expressions of the empowered feminine?

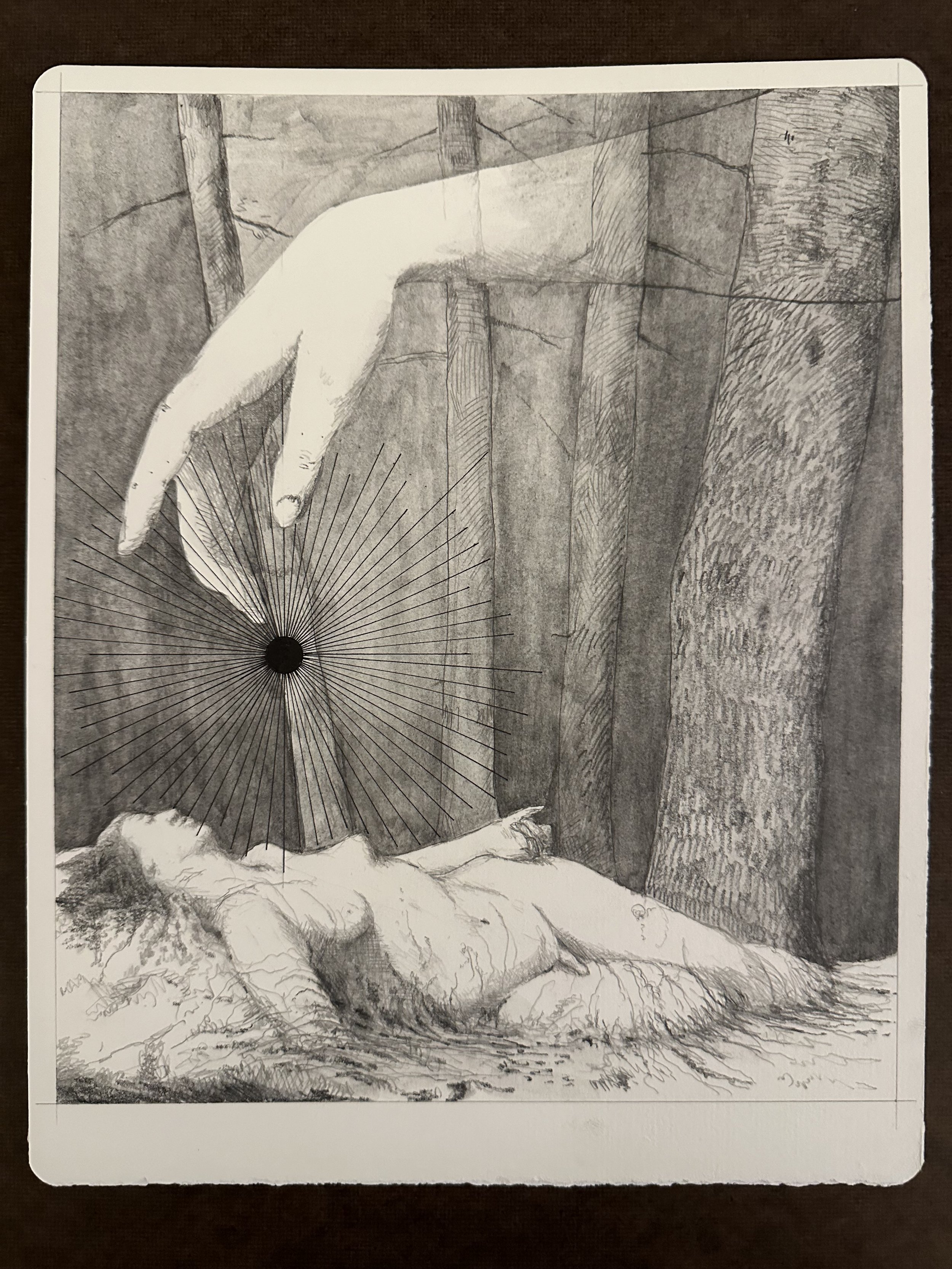

RC: I started out by making figures that were submissive and tragic, with heads buried in their hands. But over the years I saw how I and other women struggle each day just to be ourselves with our families and with society. I’m drawn to express the female body not as sexualized, but as bodies that have given birth, have lived a life, and sustained all of it. These women are the ones who are doing the hard work; they are the pillars of everything and give so much so of themselves: time, energy, love. Society doesn’t give them credit for all they give, and they become invisible as they grow old. So when issues come up having to do with women’s rights and patriarchy and men making decisions about women’s bodies, I get very angry. I want my female figures to look like they’re doing their daily tasks as warriors.

MH: That’s wonderful. An ordinary woman doing ordinary tasks is transformed into a warrior.

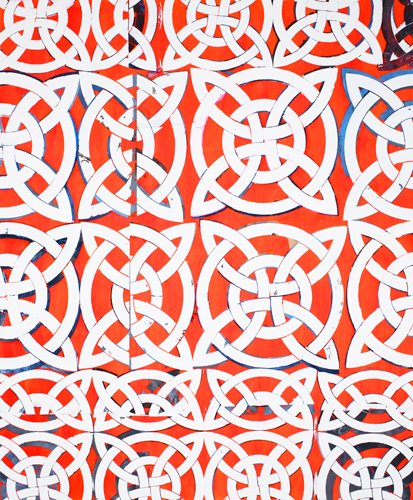

RC: Yes, absolutely. They are helmeted warriors, and I imprint Islamic designs on their helmets.

MH: Some of your works are overtly feminist, and you mentioned that your expressions of the female body are from a female perspective, without sexualization. In a patriarchal culture like Pakistan, this must be a radical expression for a female artist. What does this work represent for you?

RC: My work was very accessible in Pakistan. People understood the figures, and the fabric was not an elite material. In Pakistan, when the female form is represented it’s always sexualized, so my non-sexualized figures stood out powerfully. Pakistani women understood where I was coming from, and it was read with the same intention that it was made. This felt very successful to me.

MH: I can understand why it would be appealing to Pakistani women, because you’re choosing empowerment over sexualization.

RC: Right. My figures are inspired by Lucien Freud, who painted figures in a very non-sexualized way, even the fleshy, voluptuous women who are in sexy poses. He just paints them as they are without sexual overlays. His women seem to be liberated from all those things.

MH: How does your immigrant experience affect your work? Is there a tangible sense of “otherness”? Or perhaps it’s the same “otherness” that most artists feel; that awkward feeling of being from another planet.

RC: It’s interesting because my immigrant experience as an artist works in my favor. There are so many good artists here in the U.S. but because they’re from here, they’re not considered exotic, and their art is often not appreciated or seen. But I never wanted to use any of the exoticism from my country like so many artists do. I wanted my work to have a universal appeal, so that it could be from anywhere. So as an immigrant, I struggle like all artists. It can be very brutal, and I’ve had to navigate everything on my own.

MH: You’ve had many challenges in overcoming the loss of your home in Pakistan, providing long-term care for your mother after a paralyzing stroke, the untimely death of family members, and the fragmented memories that have been difficult to negotiate. Has your studio practice helped you to sort through your life experiences?

RC: It’s the only thing that kept me going. When my husband and I came to the U.S. in 2002 we were in California, and I couldn’t do my studio work for a couple of years because I was working in a corporate job. Even on my days off when I tried to work, I had no connection to my work, and this feeling would just kill me. This went on for years, until I left my job and we moved to New York, and here we created a different life. Not being able to work in my studio makes me anxious and unhappy, because it takes me away from myself. For me, being an artist is not a privilege, it’s a need.

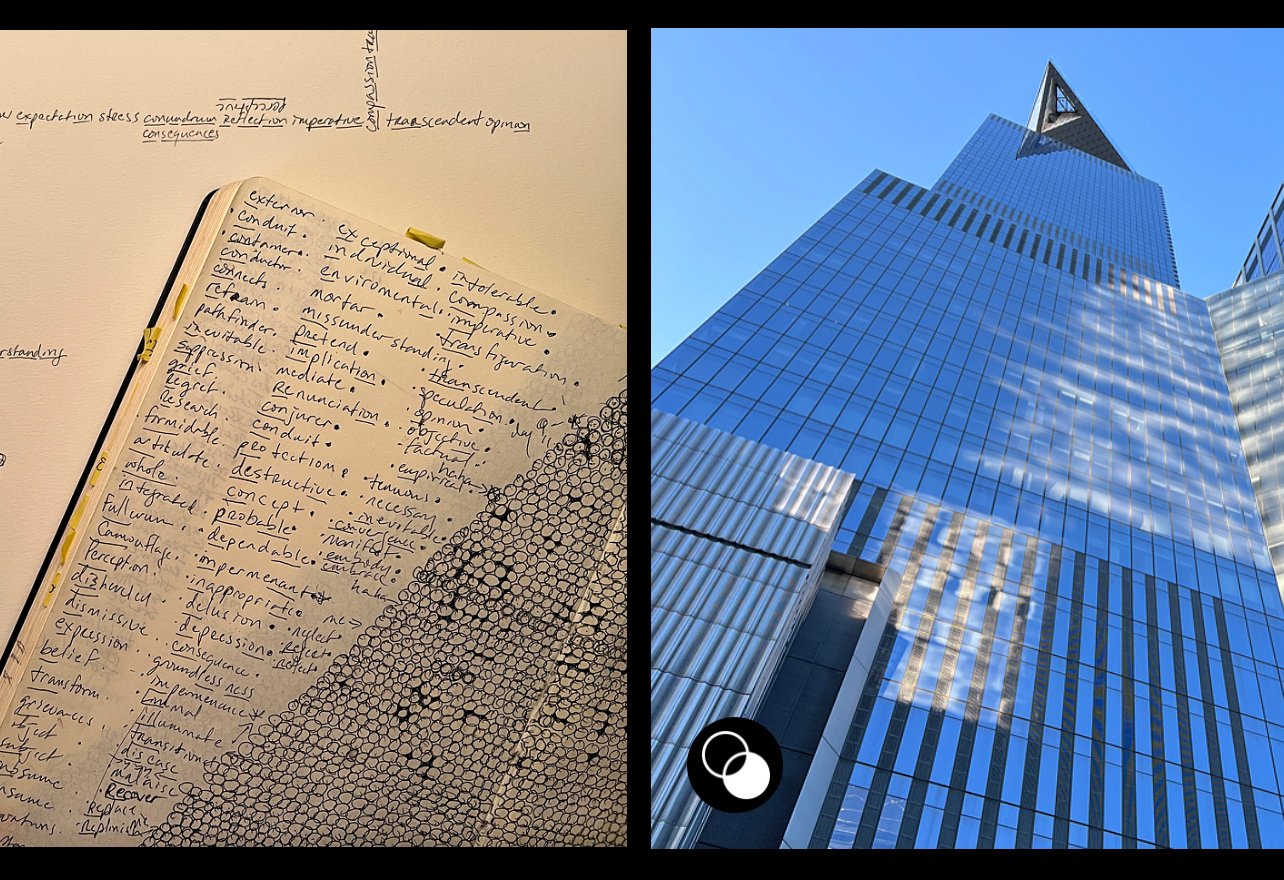

MH: When it comes to art as a form of therapy and personal transformation, wherein does the healing take place? Which part of the process?

RC: I think healing happens when you make your work. It comes from everything, from choosing your materials to deciding how you’re going to use them, and then knowing what you want to express with them. Healing takes place when you are your own master, when nobody is dictating to you what to do and how to do it. I think the best way to process the things that happen to you in your life, no matter if they’re sad, tragic, or happy, is by working with materials and process. This is the contribution that artists give.

MH: Do you think that having one’s work seen by others is an essential part of an artist’s process? Say an artist completes a beautiful body of work, takes a victory lap, then throws it on the pile and starts a new series. Is that enough or is there something inherently meaningful about sharing one’s work/self with others?

RC: To some extent it’s enough when you know that your work is good and that you’ve created what you wanted. But I also think that art is meant to be seen and shared, so if you toss it aside without showing anyone it would be tragic. It would be very sad that no one else would have the opportunity to connect with it and know who you are. I make my work accessible to people and it’s not too abstract because I want the work to be meaningful. We have a deep connection with the rest of the world through our art.

MH: Looking back on your life, do you think the personal losses and suffering show up in your artwork? And if so, does it feel tragic, or is there a beauty in it as well? Have you been able to transform the loss into something else?

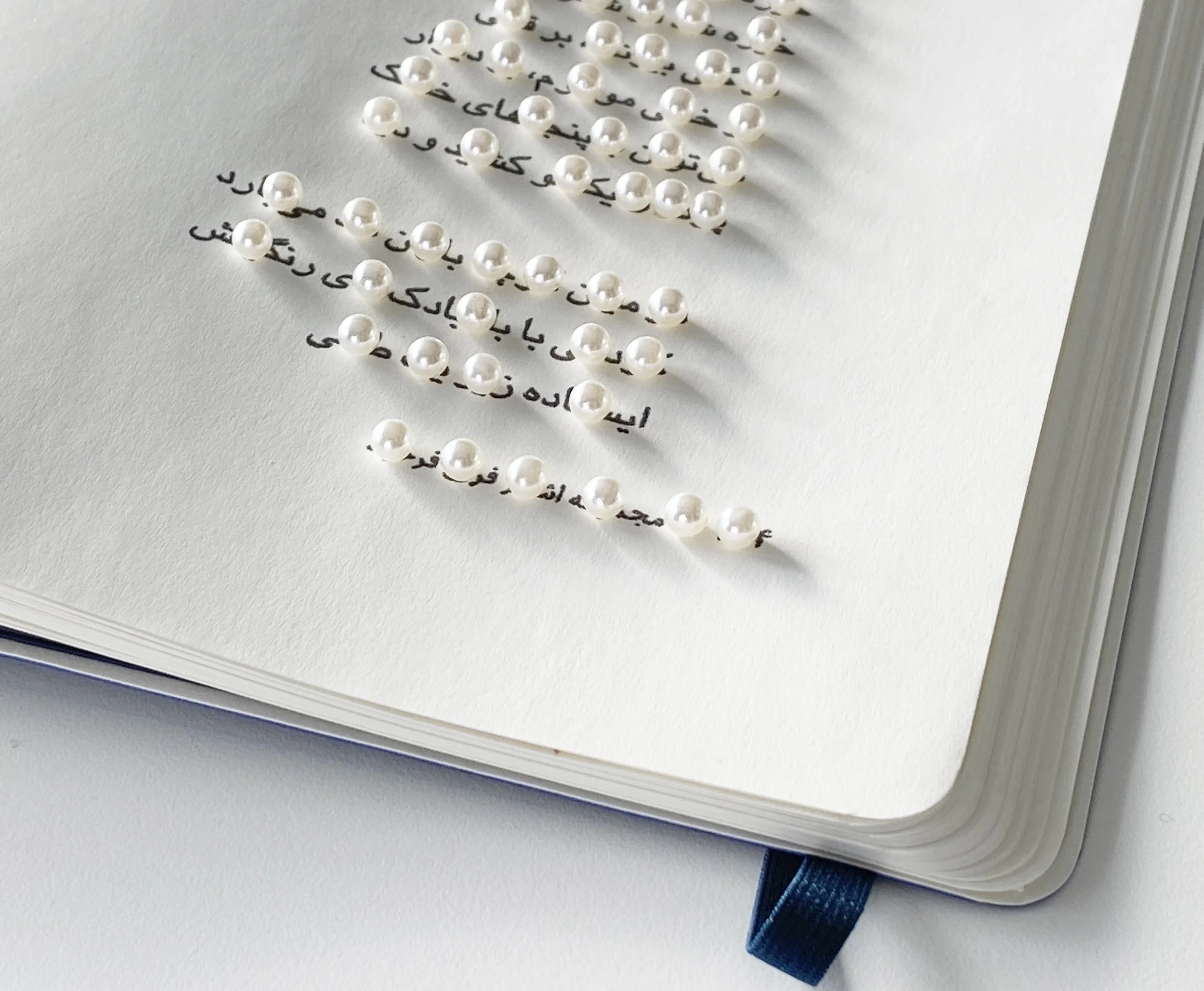

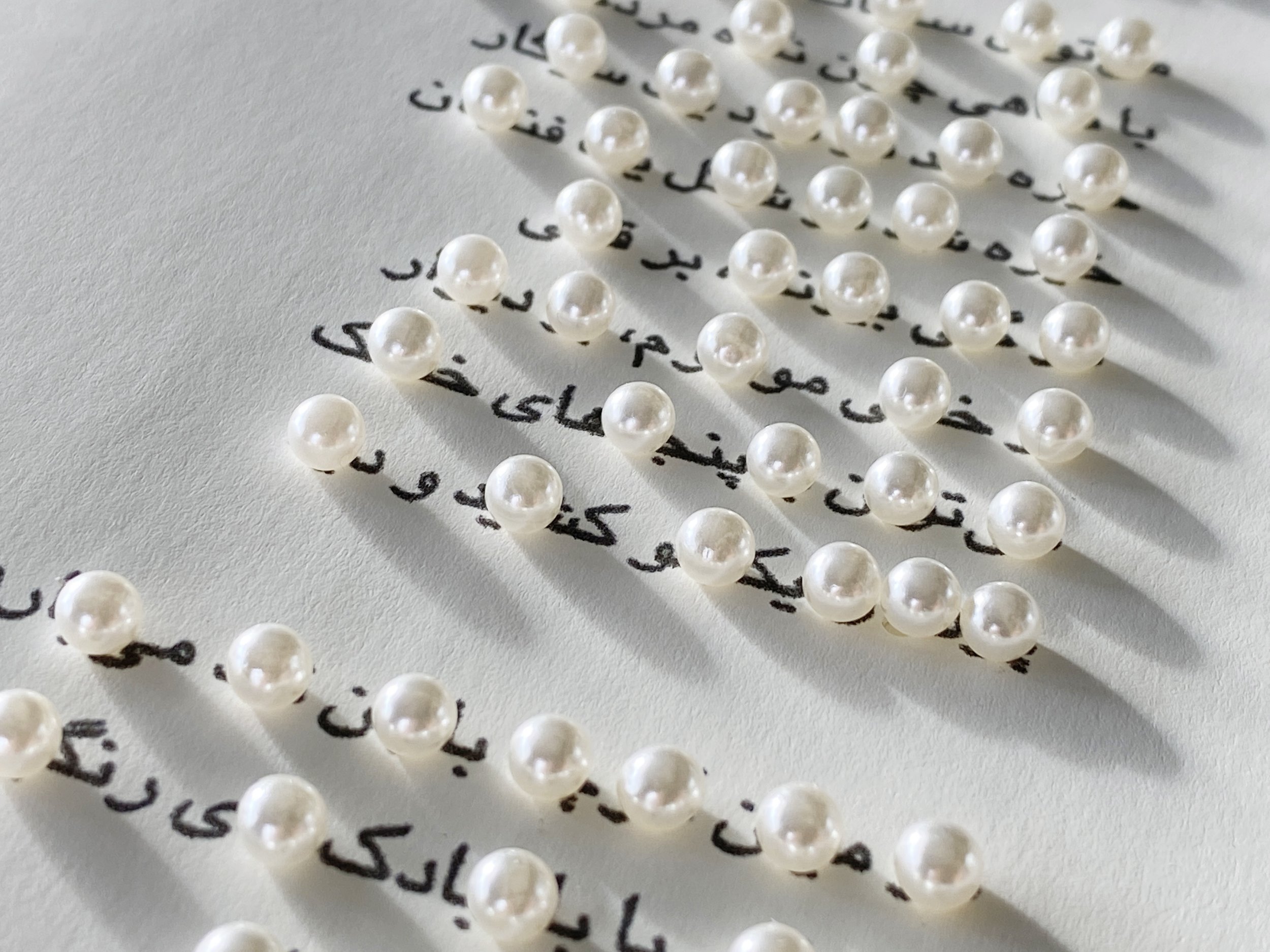

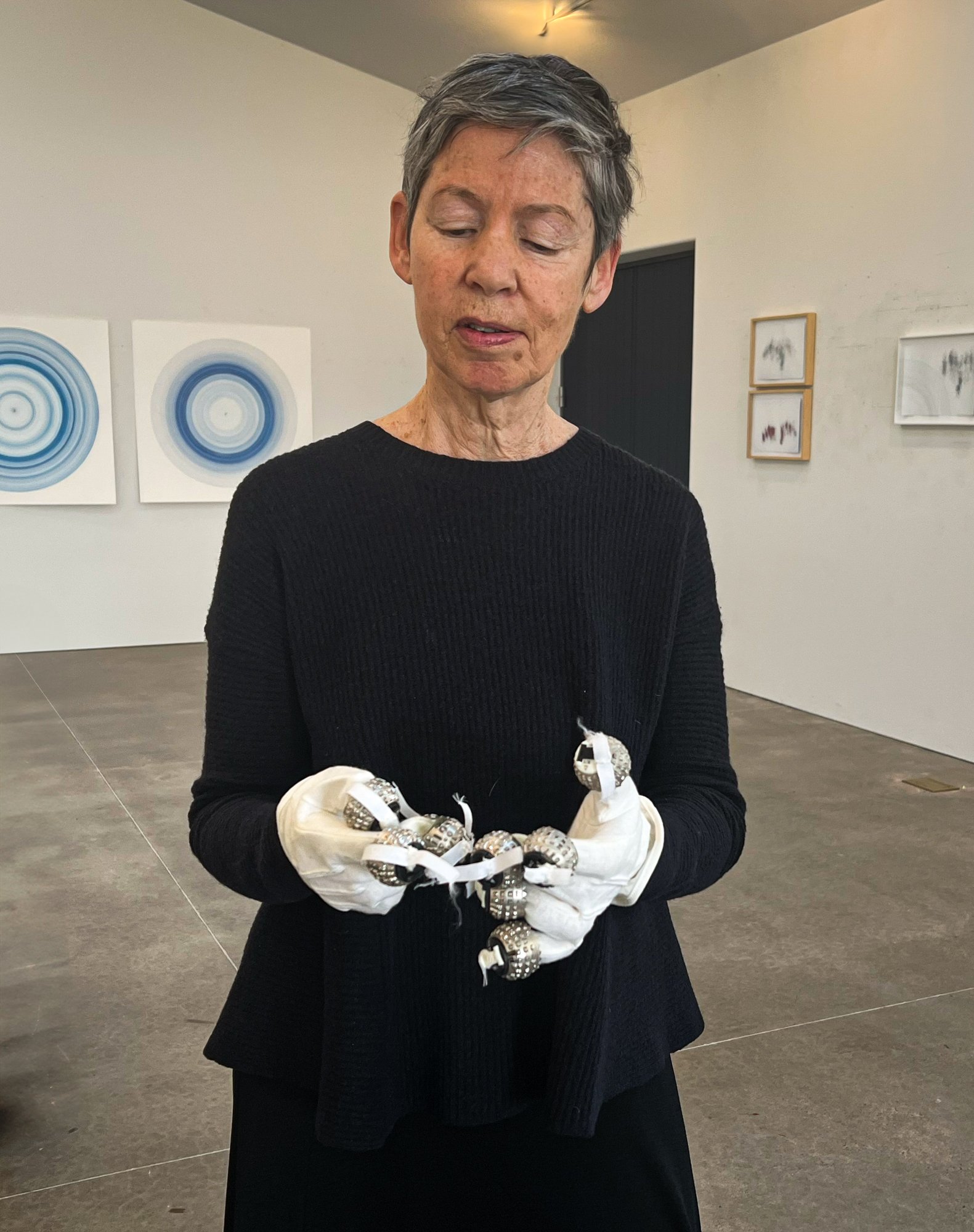

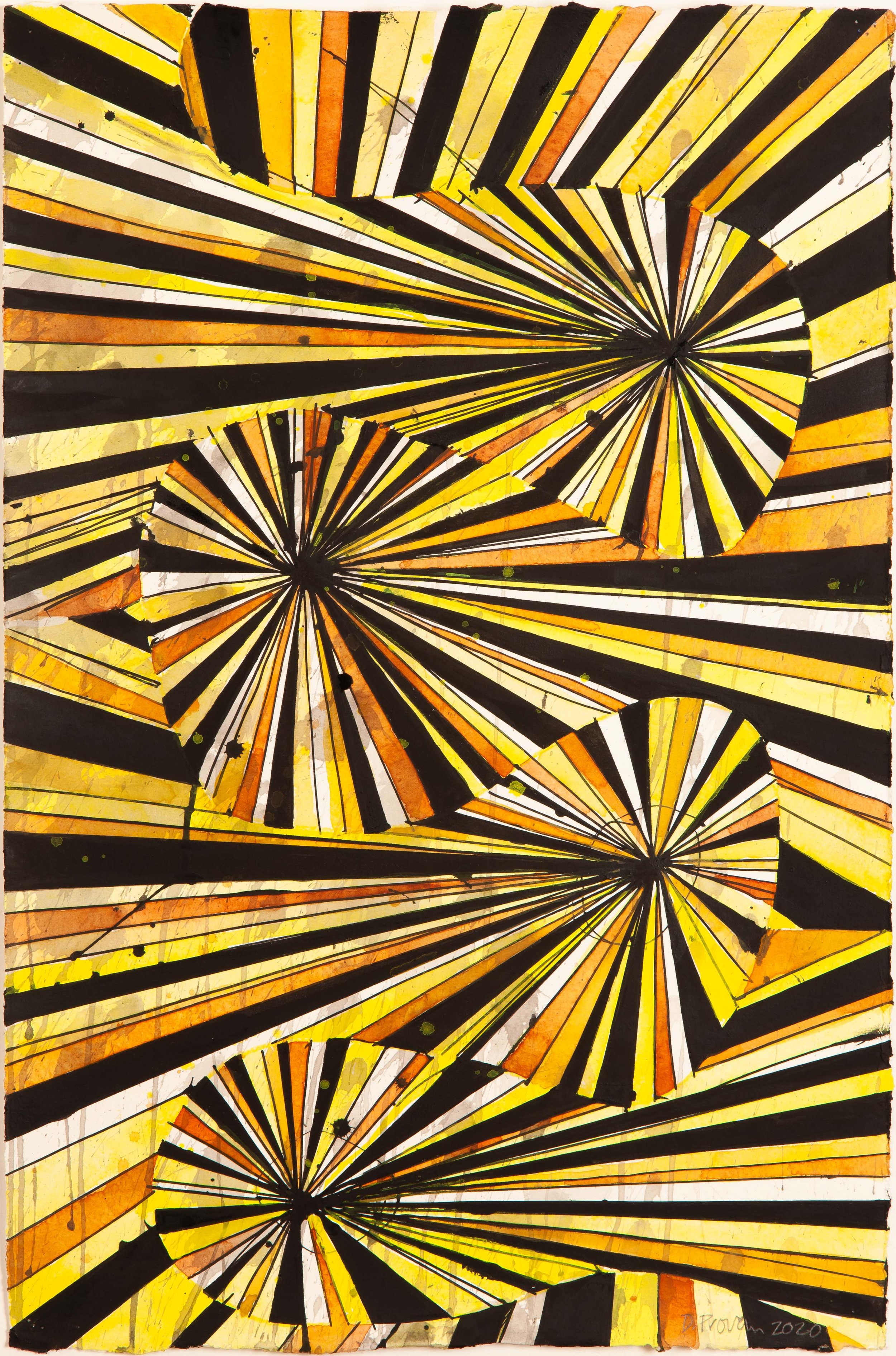

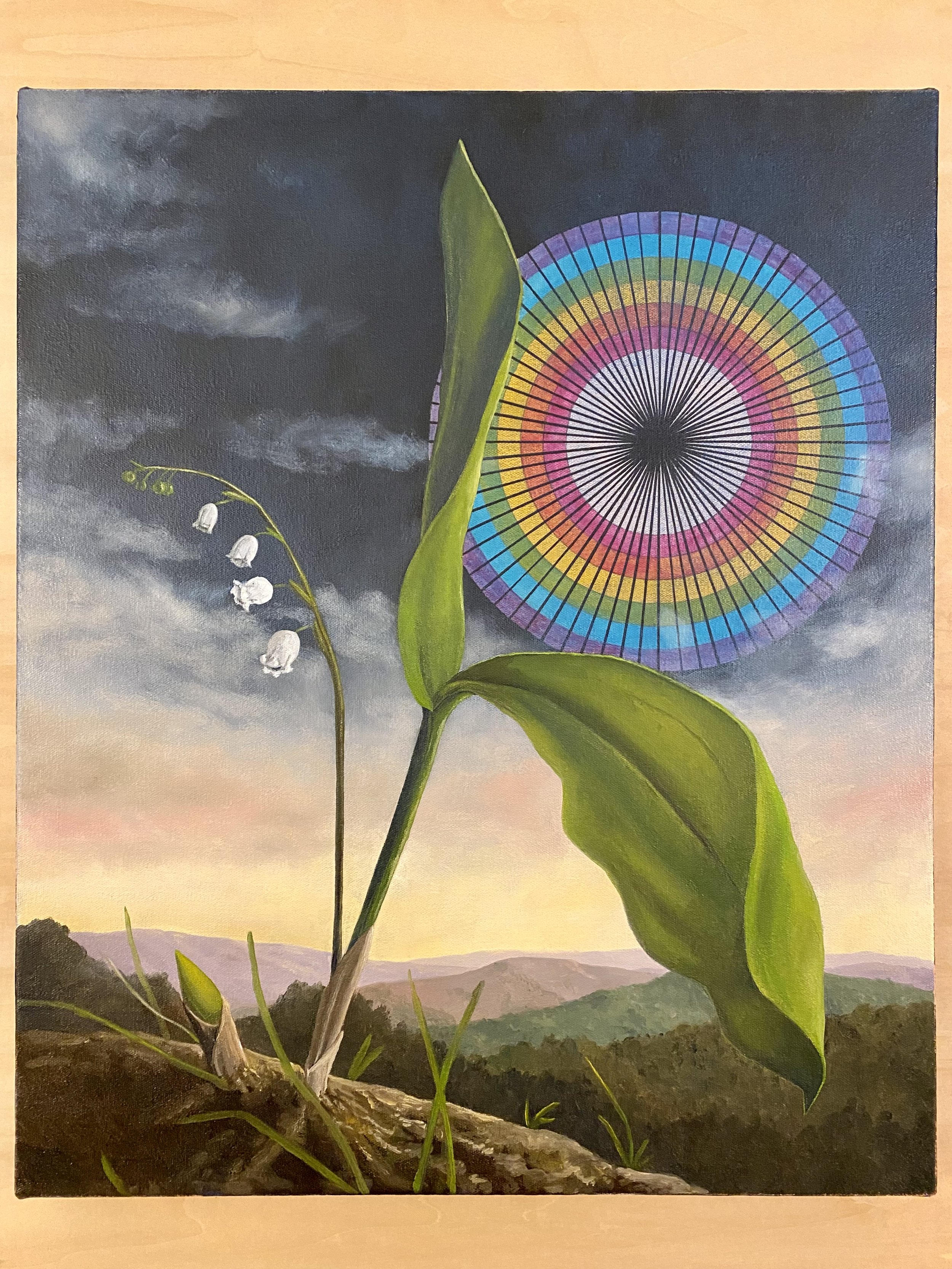

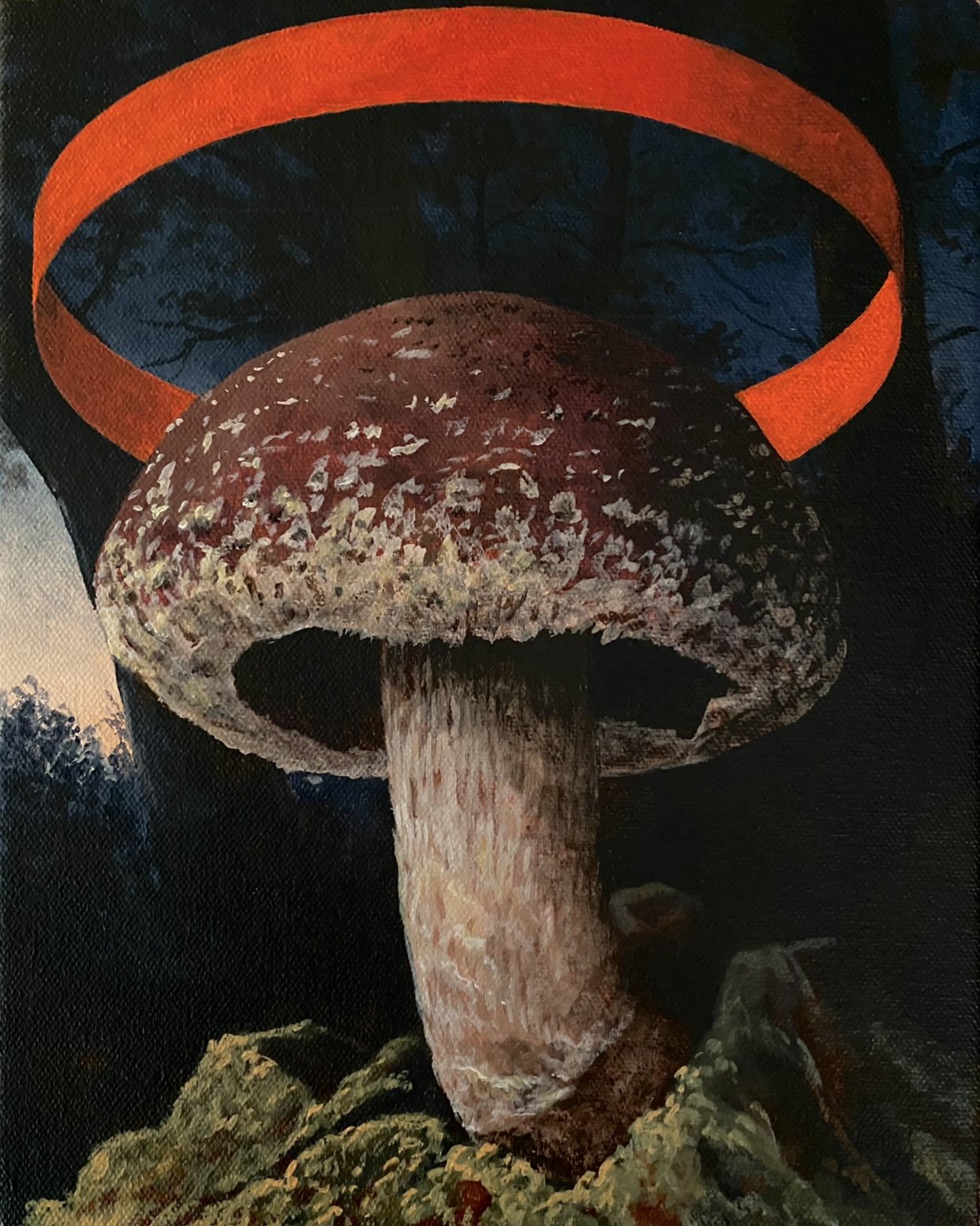

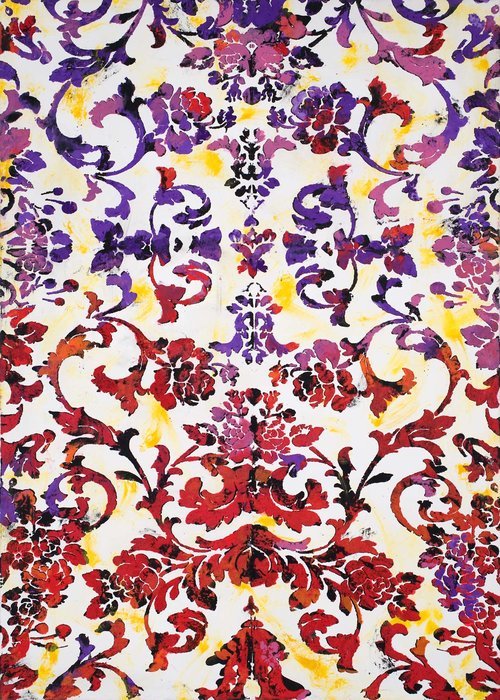

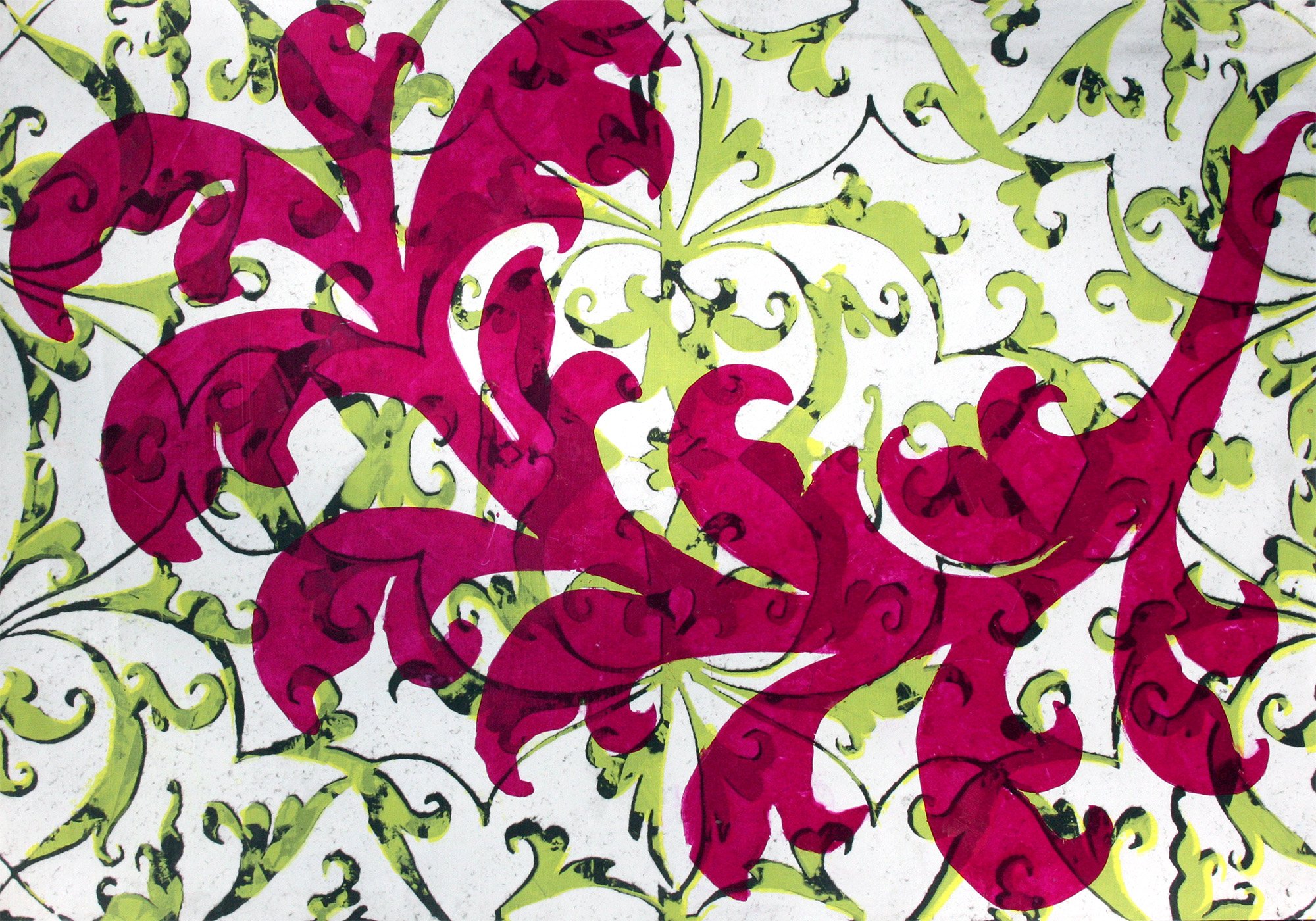

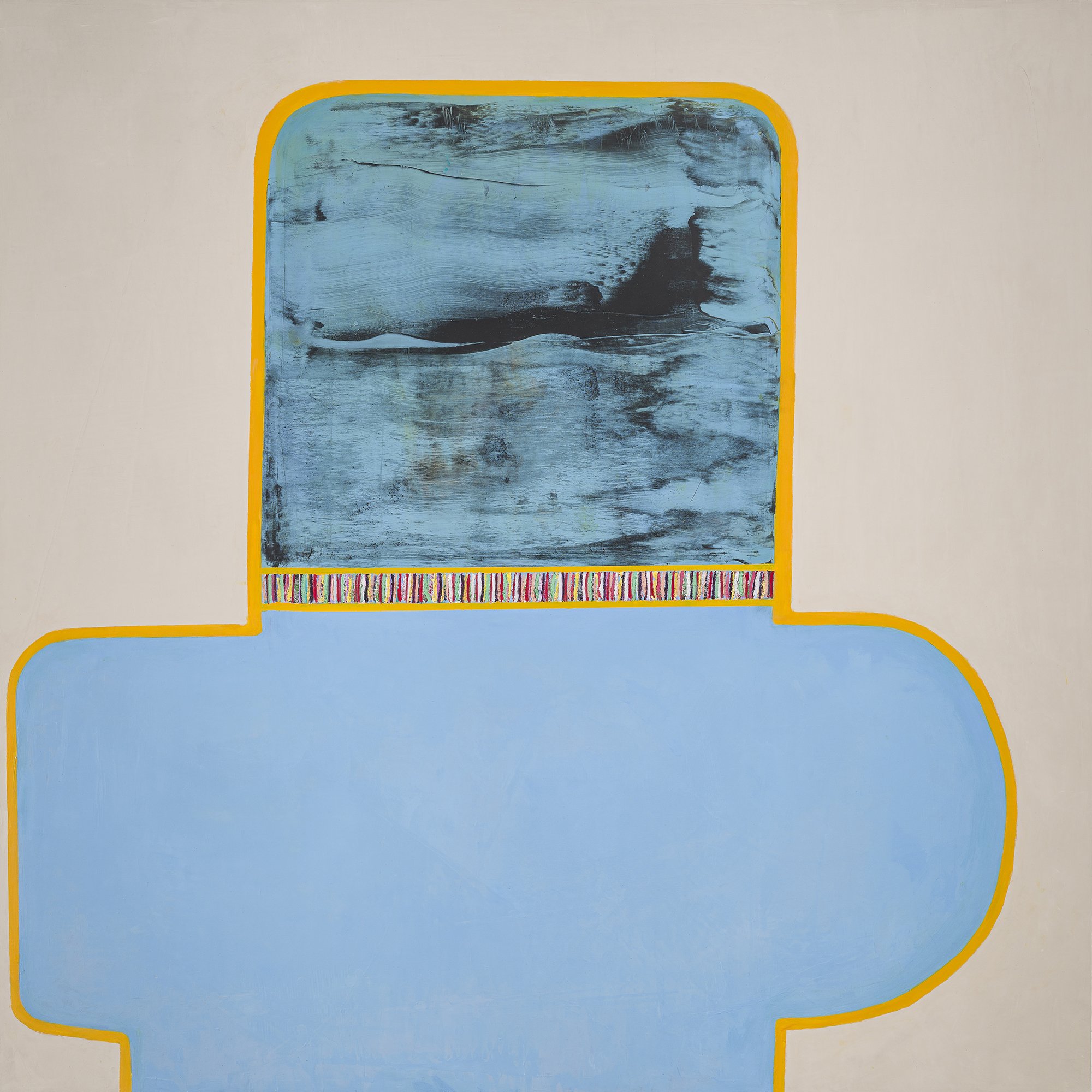

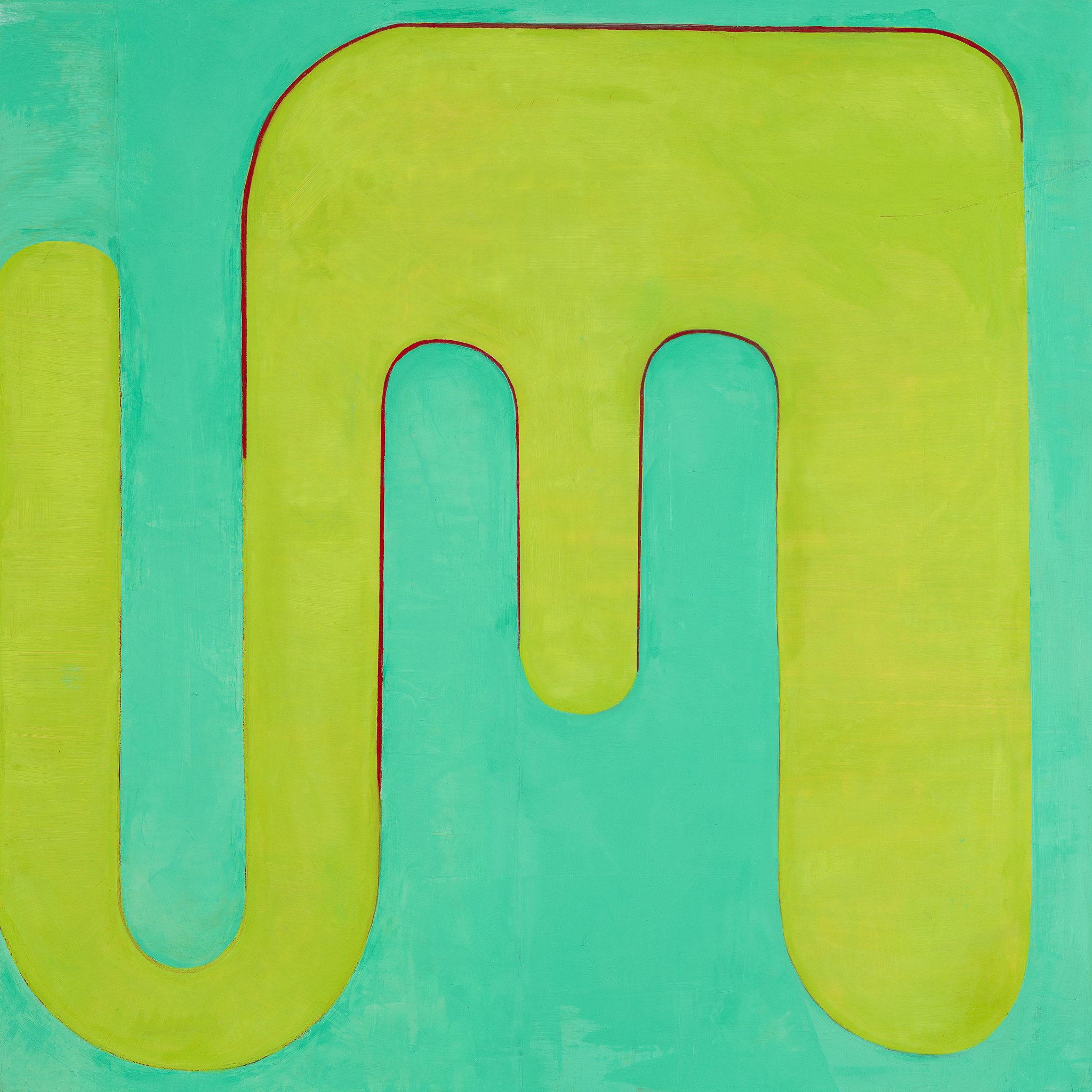

RC: Oh, definitely. My early works were very tragic, because I had suffered huge loss, and maybe I was indulging in my sadness. So I learned a language to express that sadness, and I felt that it was really good work. But the work has grown with me, so as I’ve grown out of grief and struggle, the work has grown as well. My older work was always made with materials like muslin, black cloth, and dyed grain sacks, but my current work is bright and beautiful, and the materials have their own language – there are sequins and other materials that I hadn’t thought of using before. Whatever you feel, that’s what you create. And eventually when you grow, your work becomes that new expression.

MH: But it’s not all sequins and butterflies now, right? Because the sadness will never go away, but you bring joy to it as well. That’s the fullness and depth of art, music, literature, and so forth.

RC: Yes, exactly. It’s not that my current work has no sadness, but there’s so much more than that, and it can be experienced in the work.

MH: What’s the best part about being an artist?

RC: It’s the freedom, the space that you enter, both physical and psychological, where you can express anything – visible, invisible, or abstract. And then there’s the vulnerability that an artist experiences when they step into the unknown and they don’t know what it’s going to look like, whether the material is going to work, or if a piece will be successful. When you put yourself there, knowing that failure is a possibility, those are the moments that I think are so precious. If you know everything ahead of time, where is the joy? As life is unpredictable, as life is vulnerable, so is the artist’s journey.