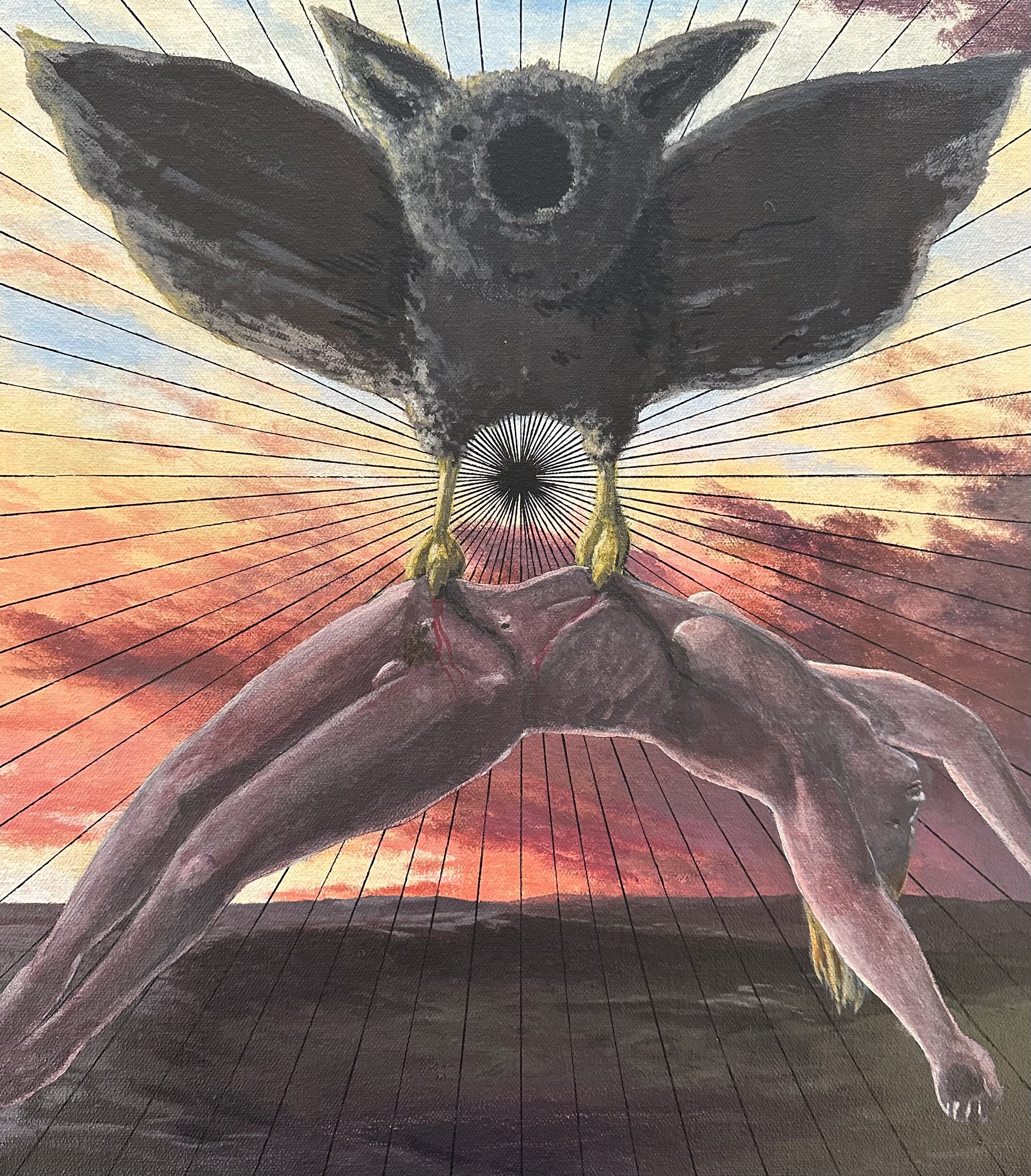

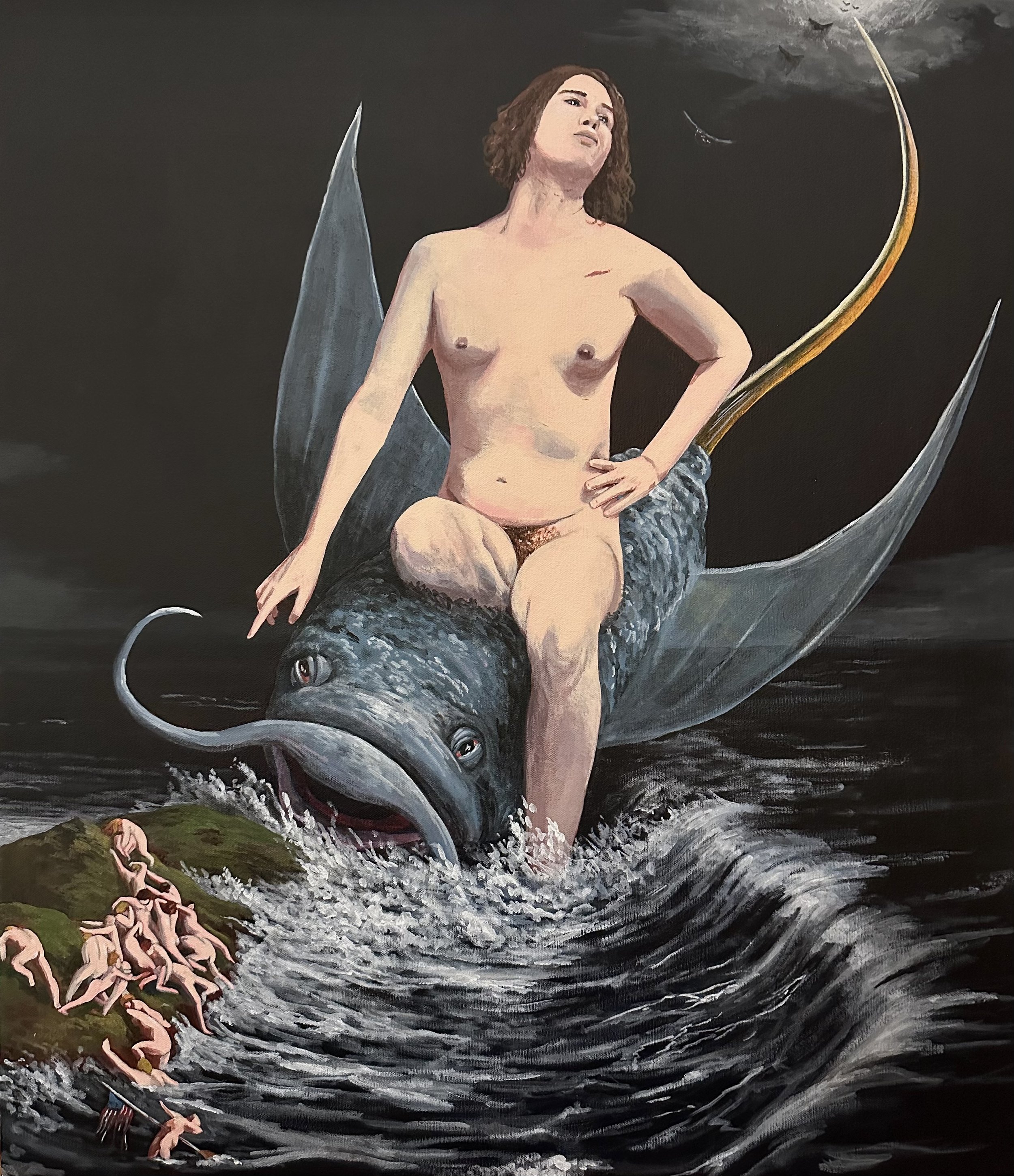

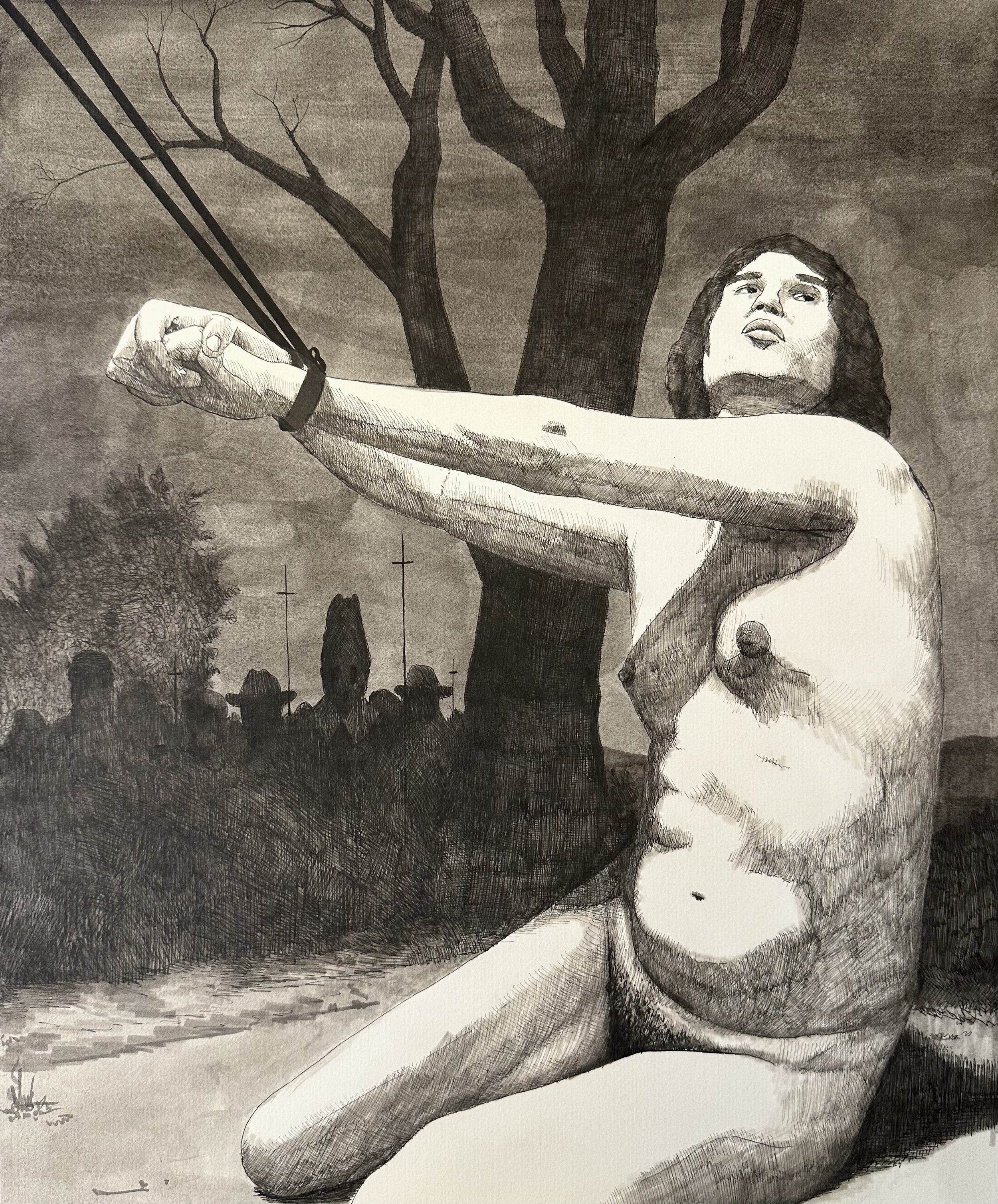

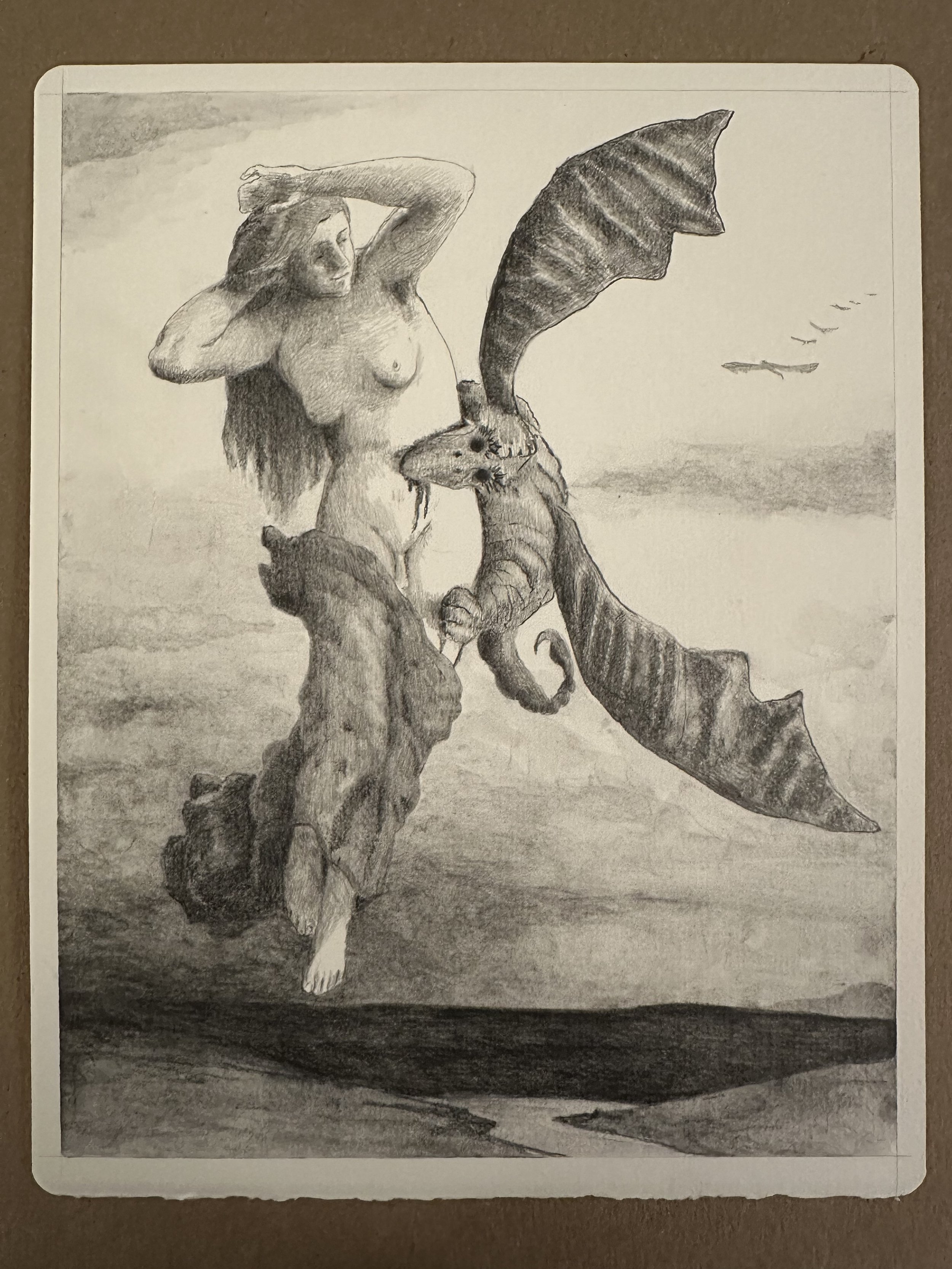

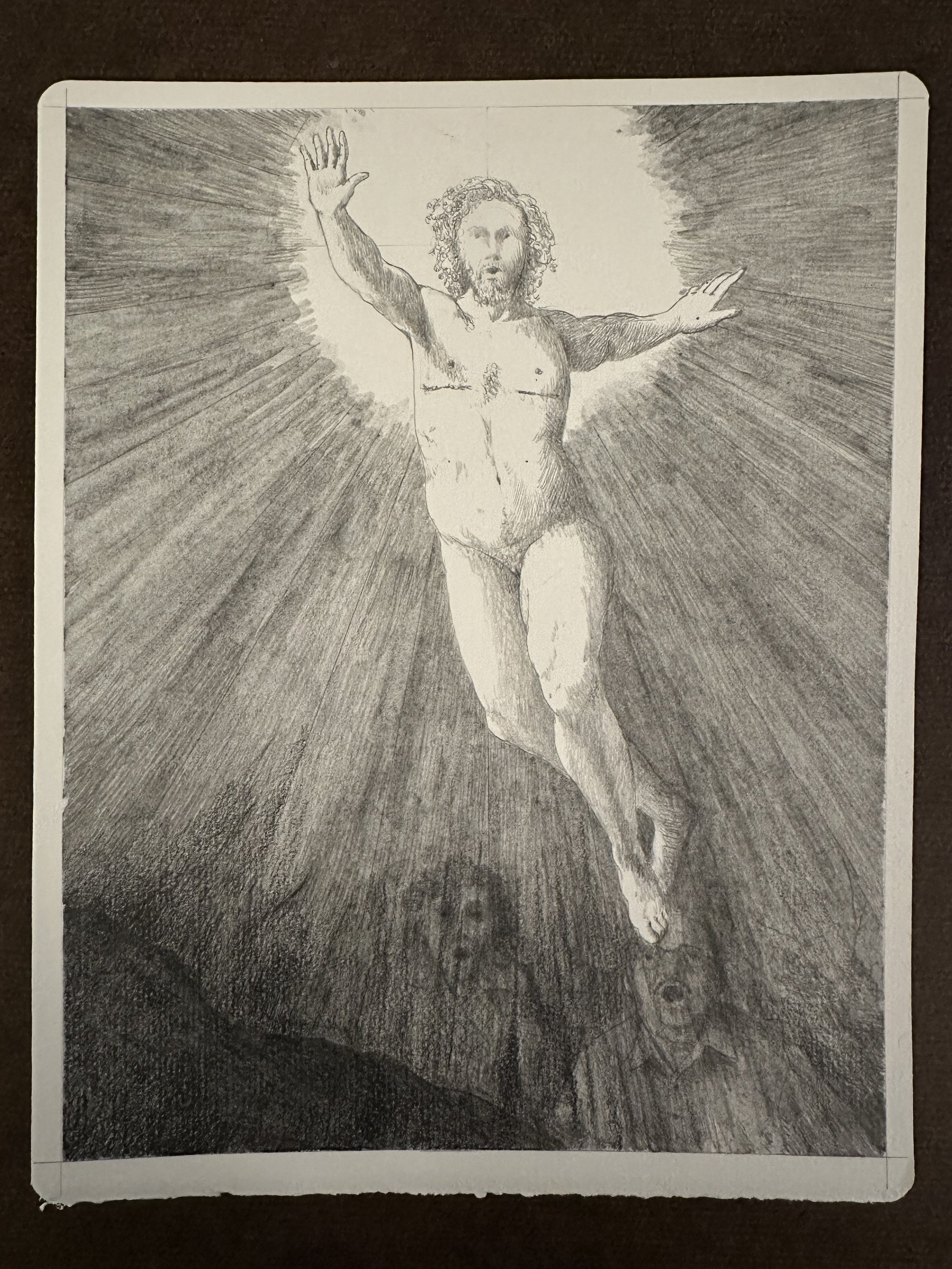

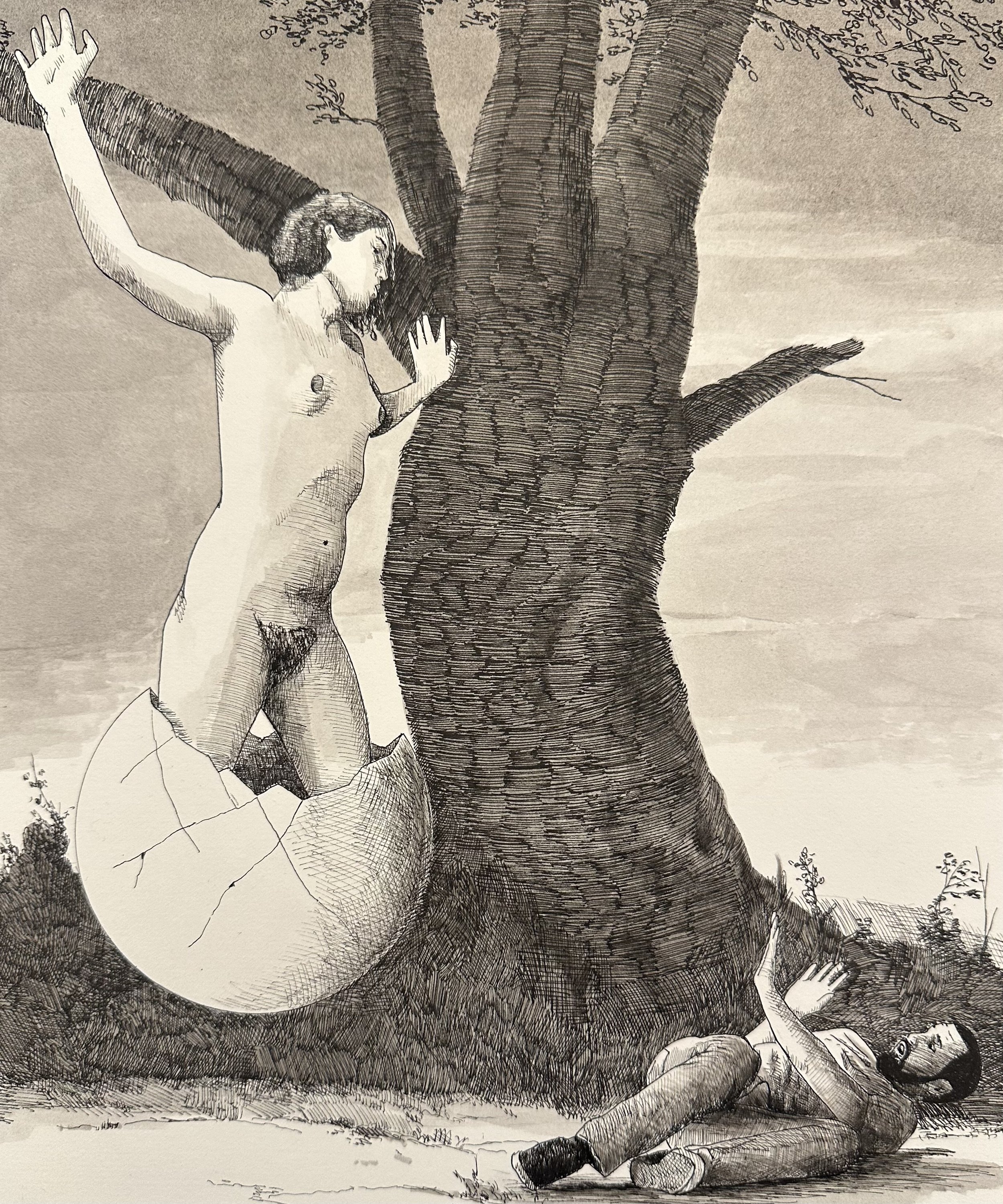

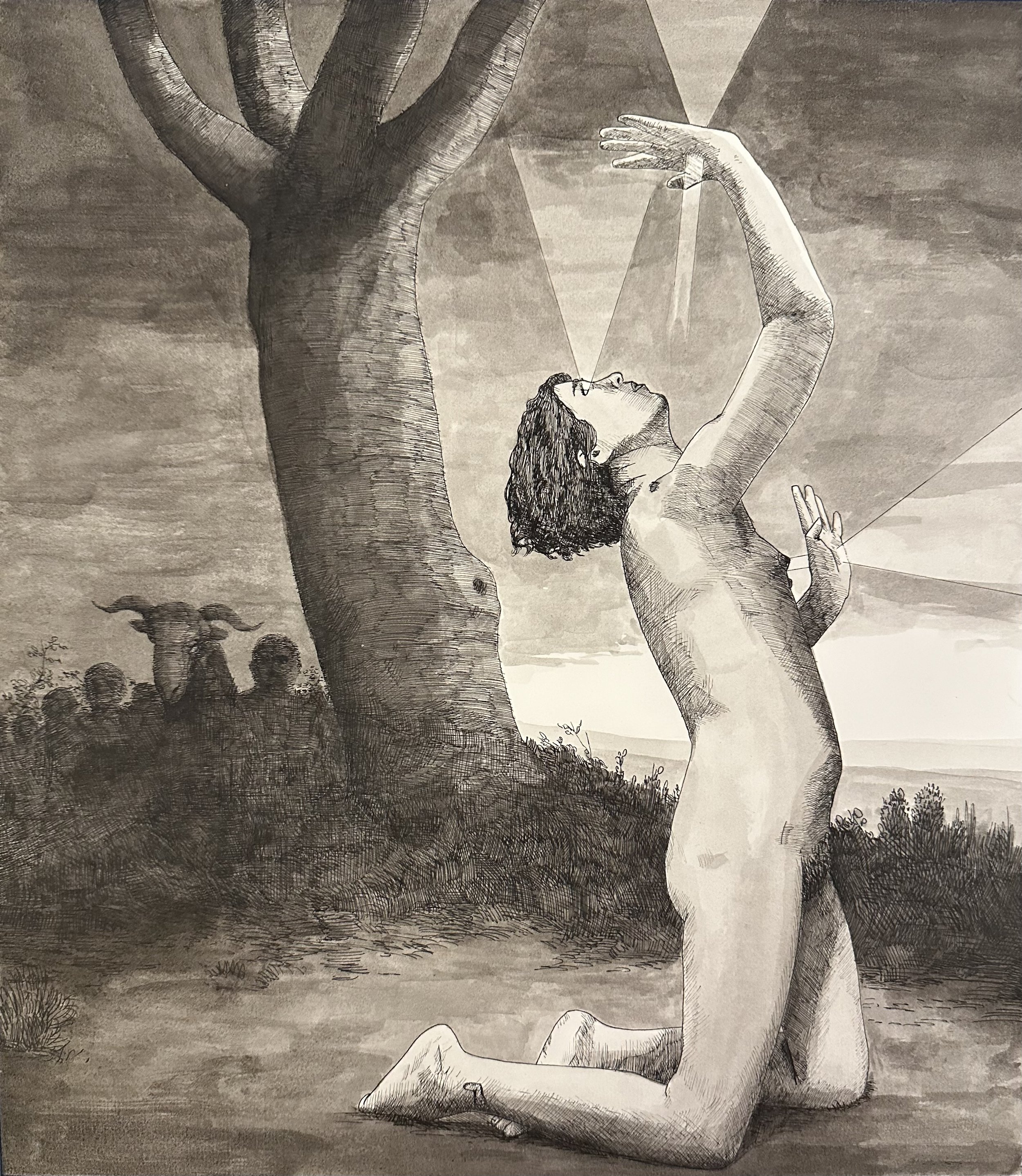

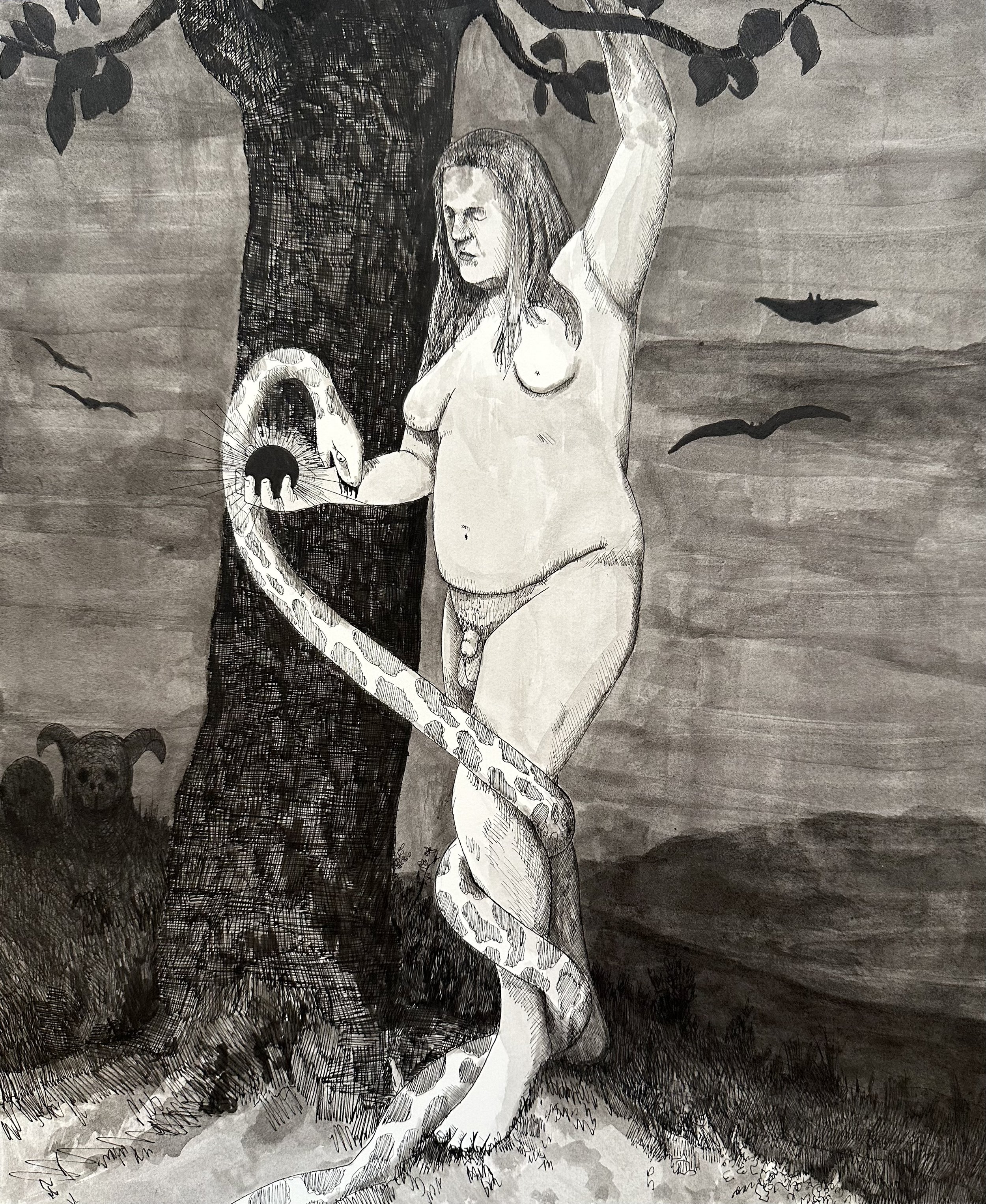

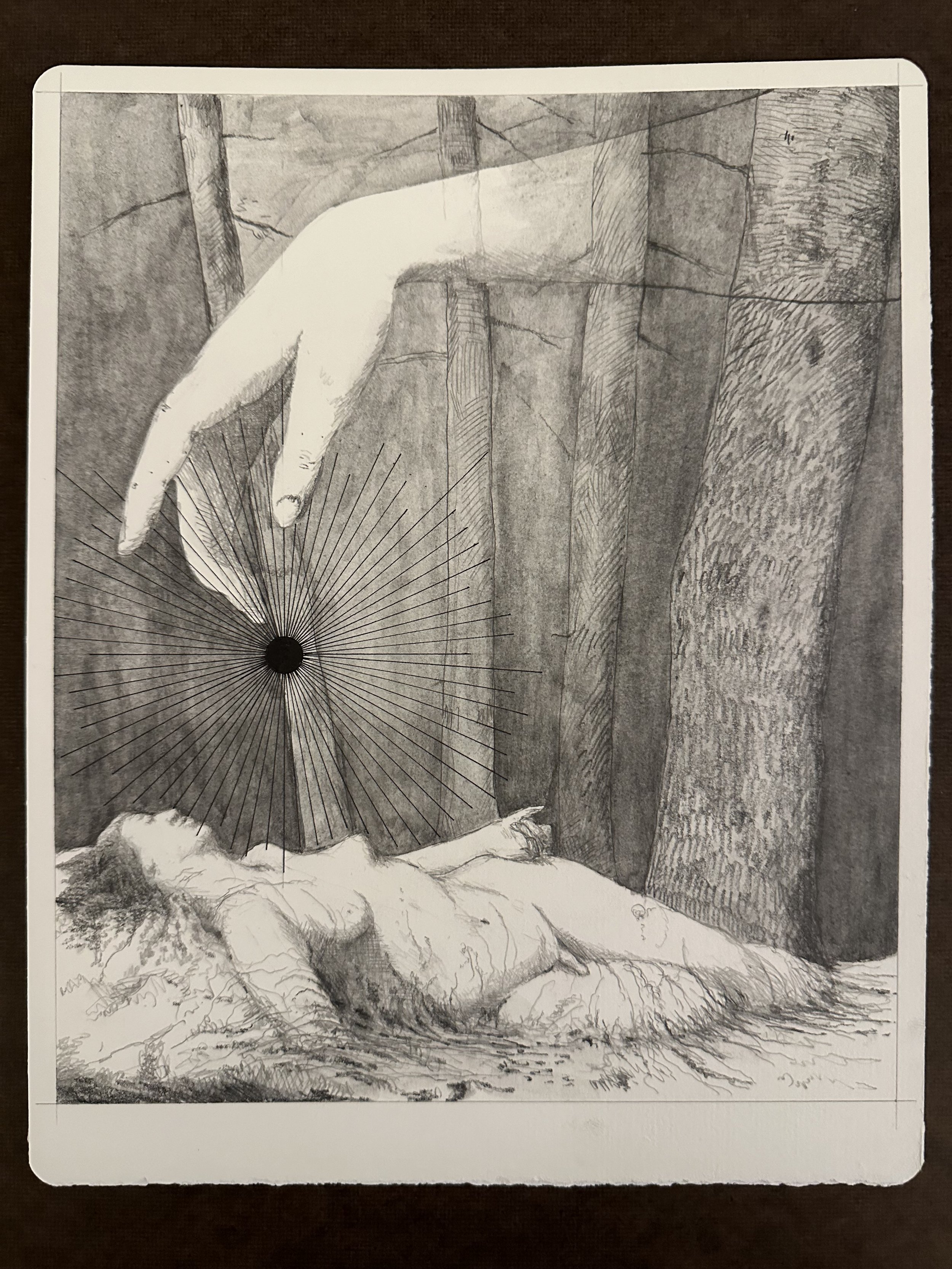

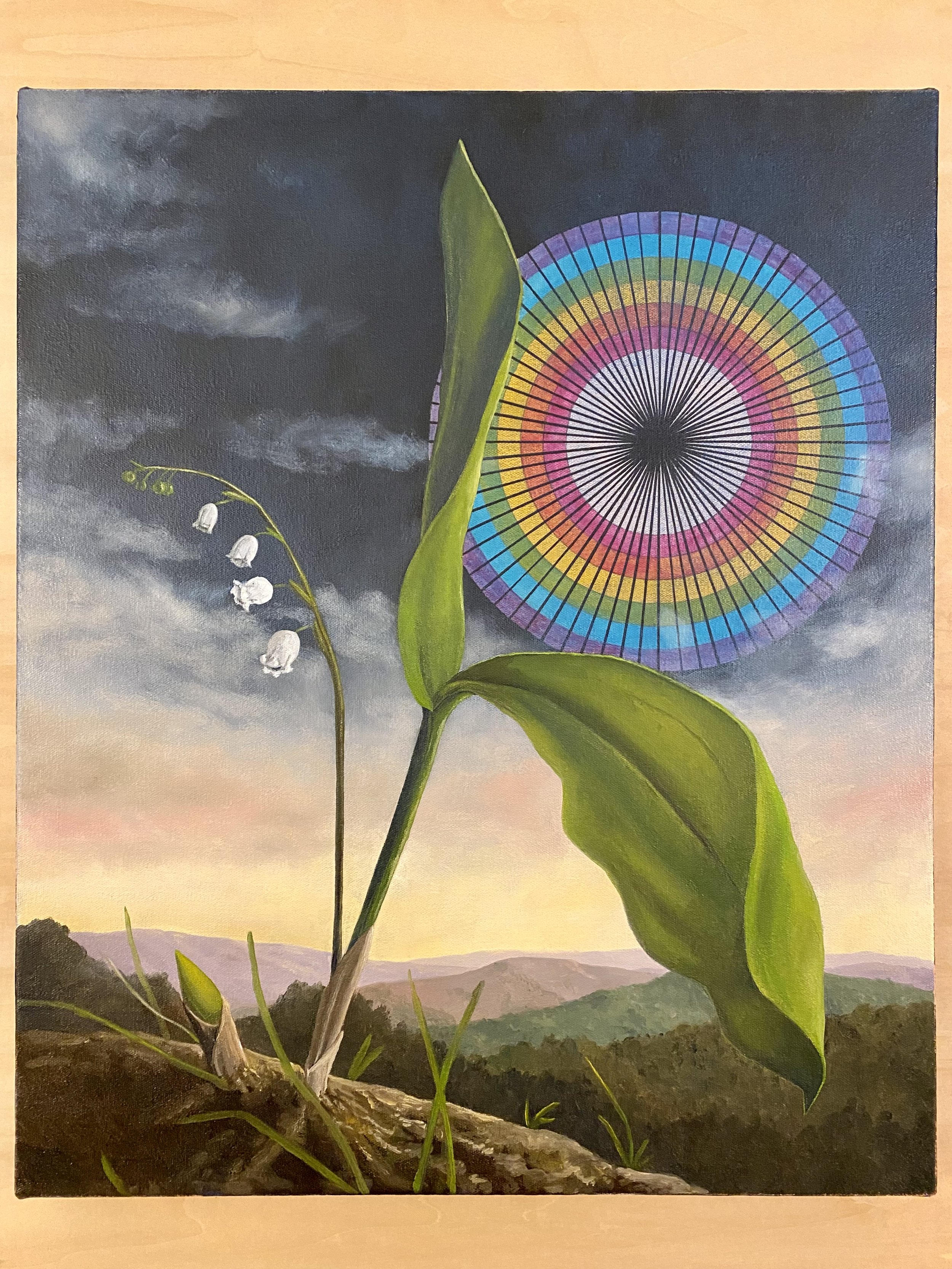

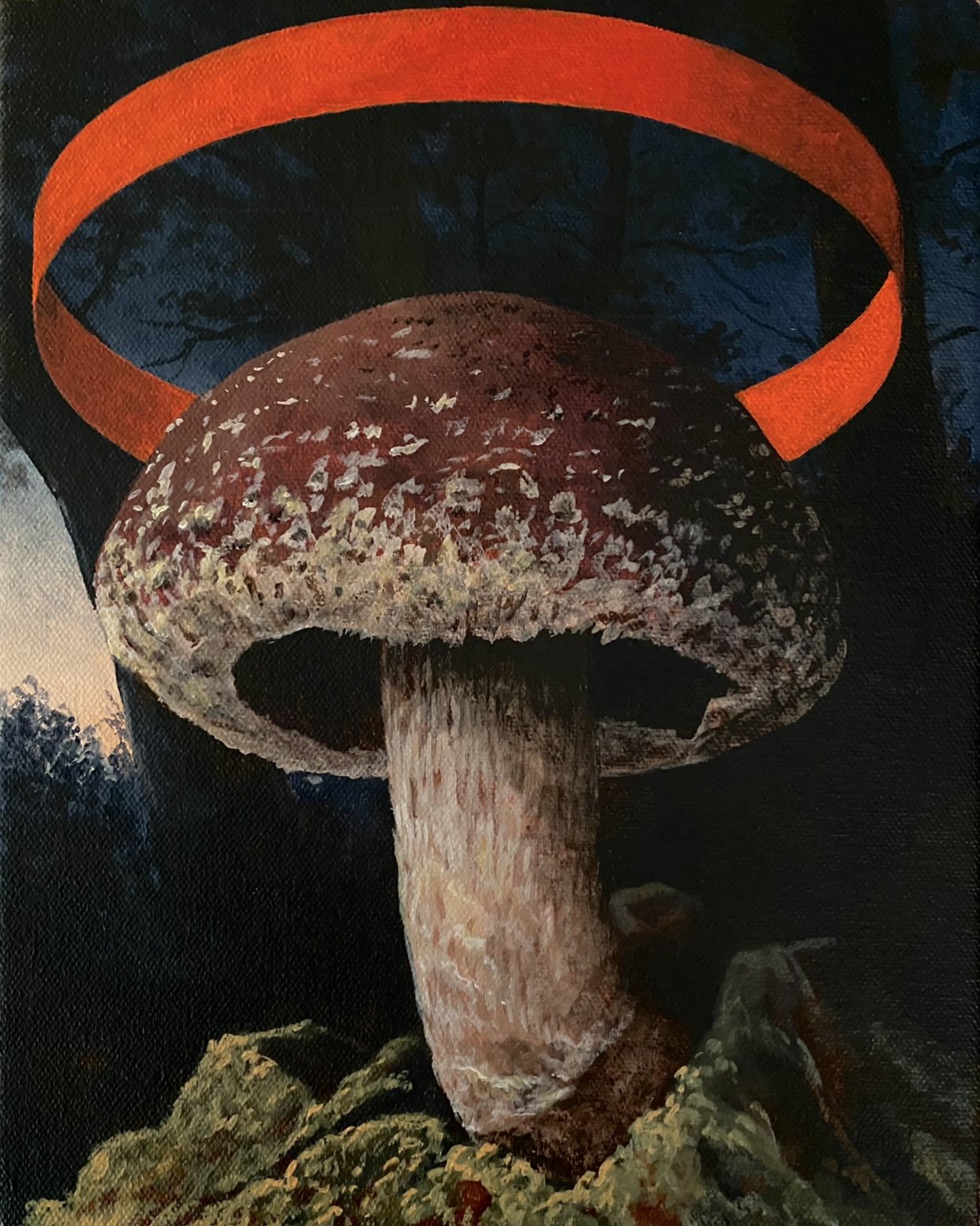

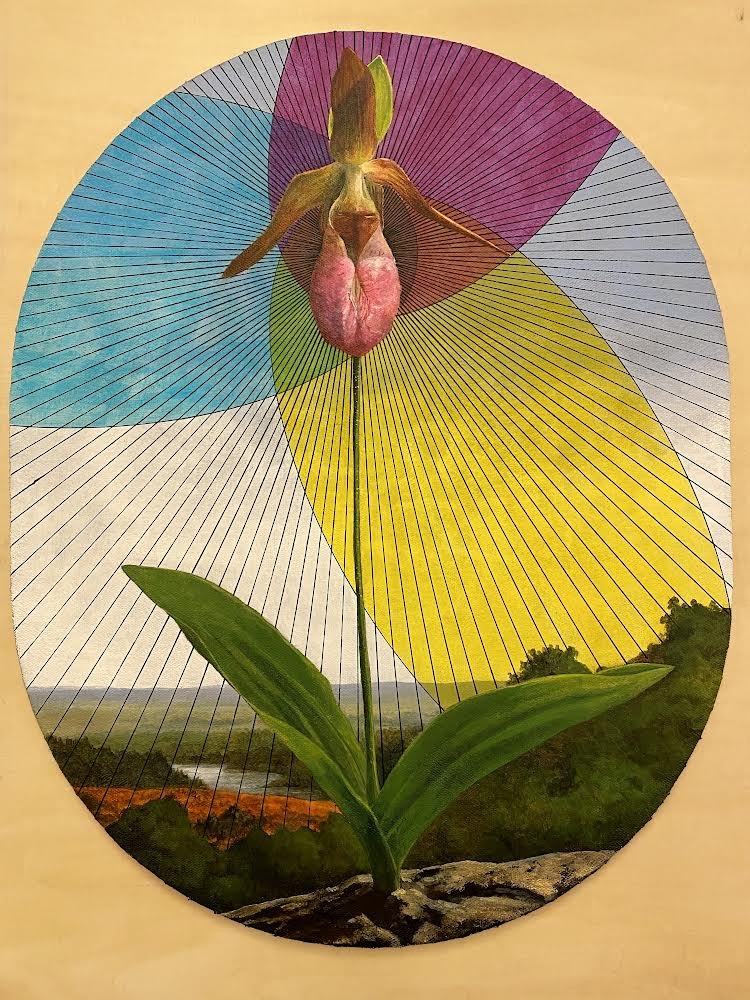

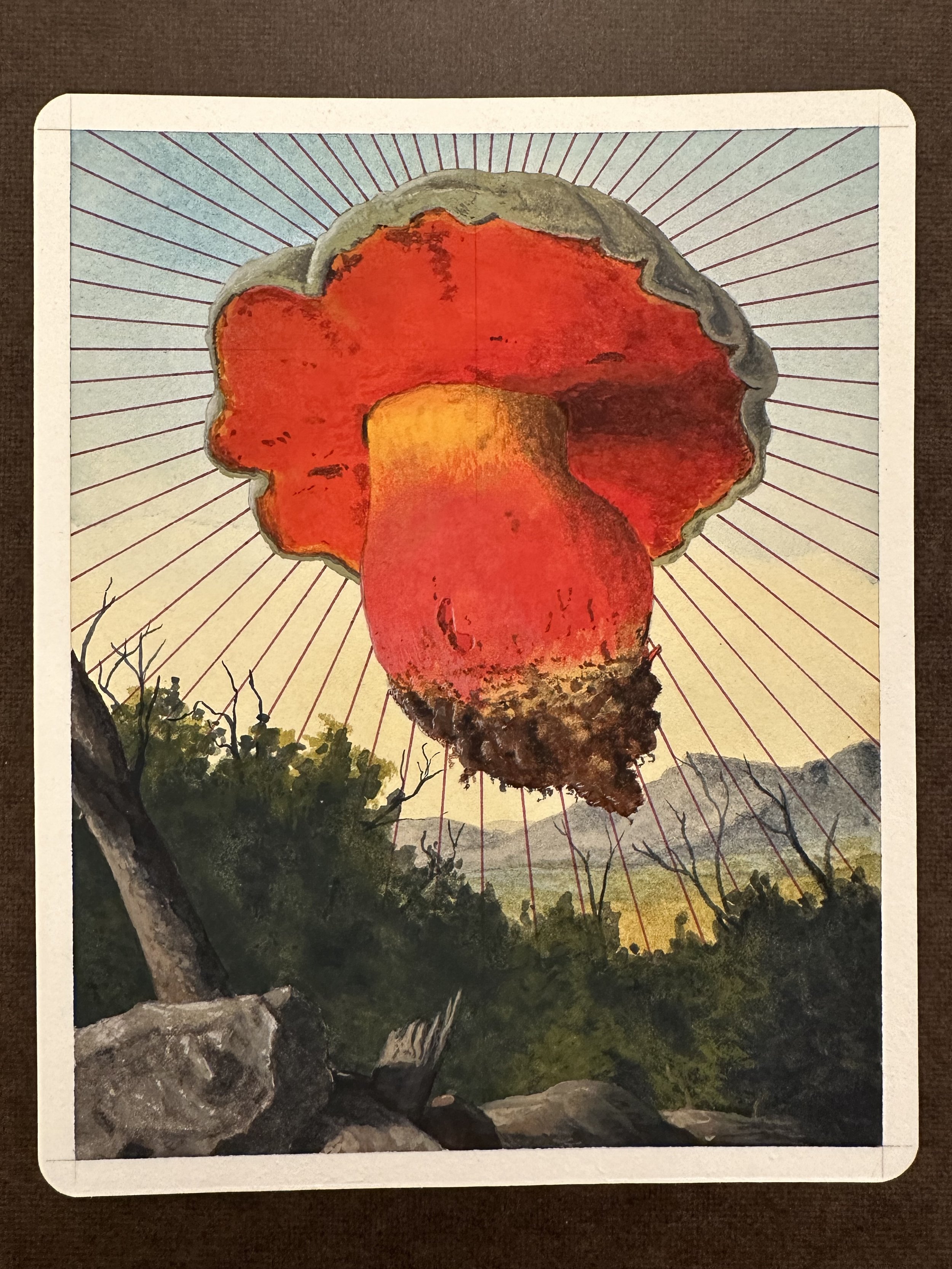

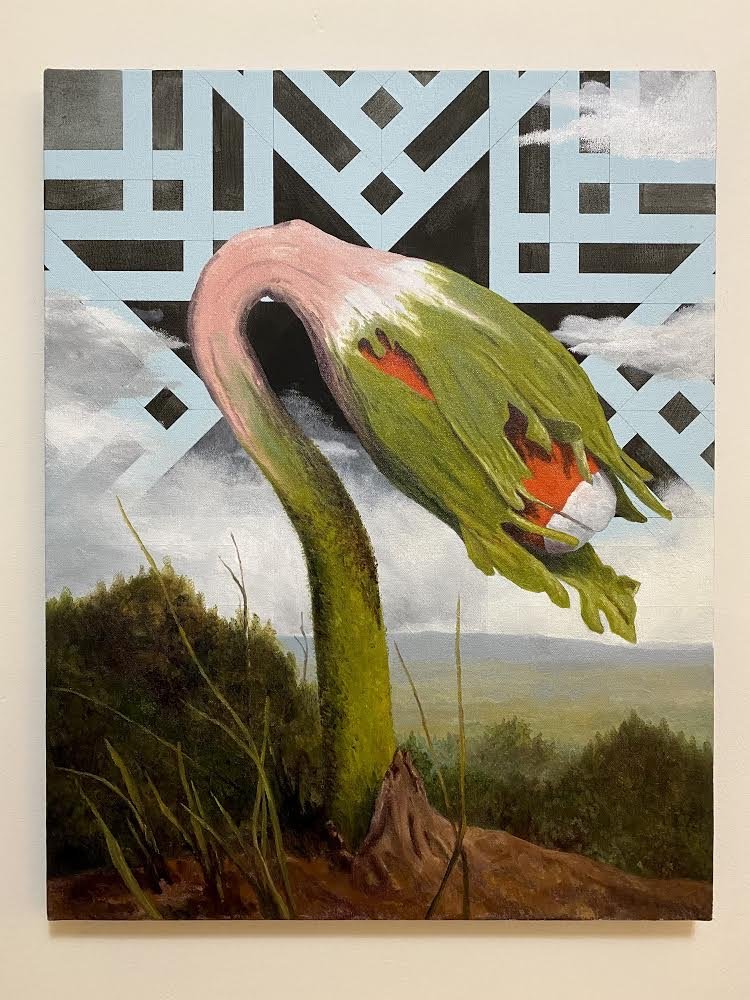

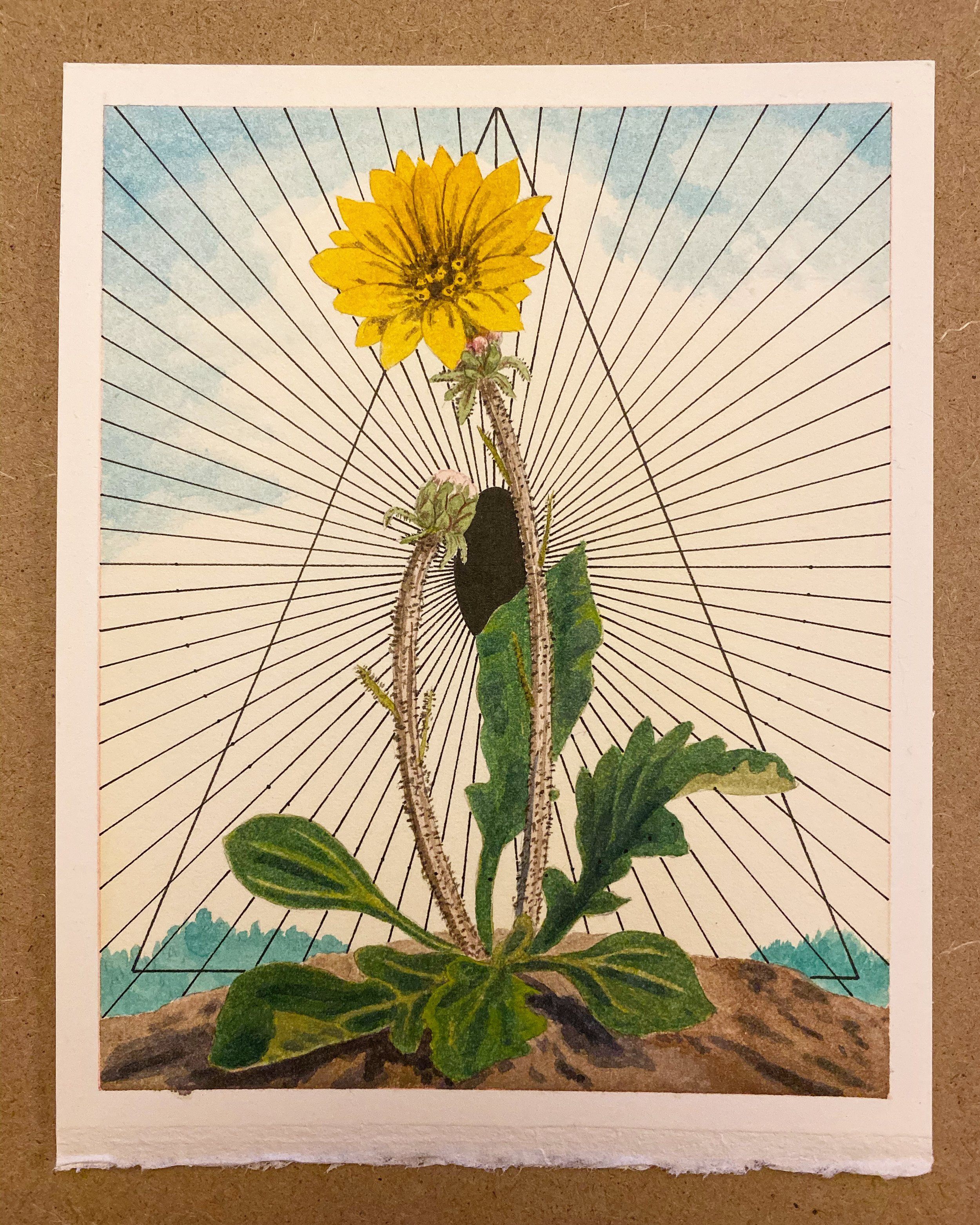

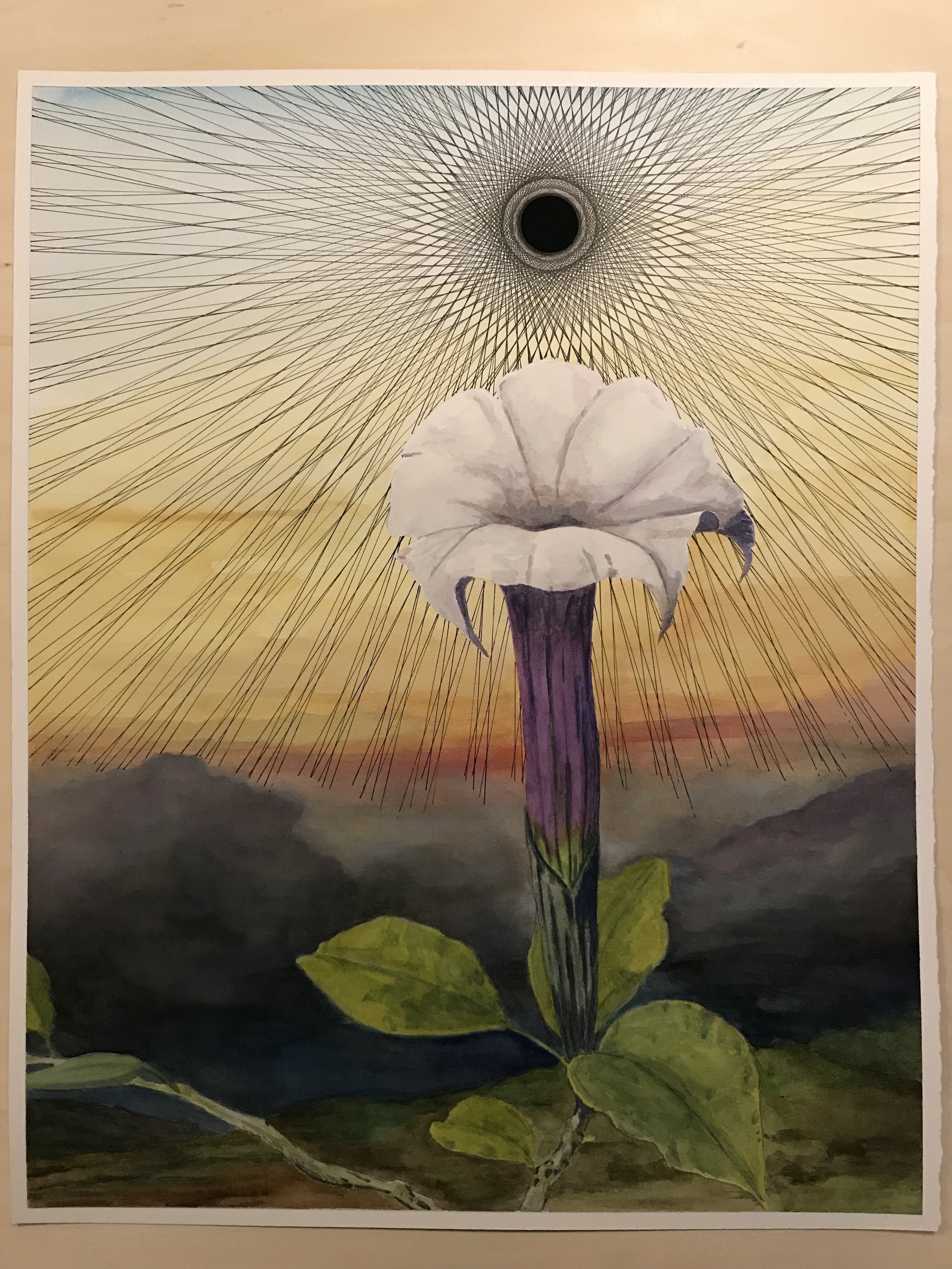

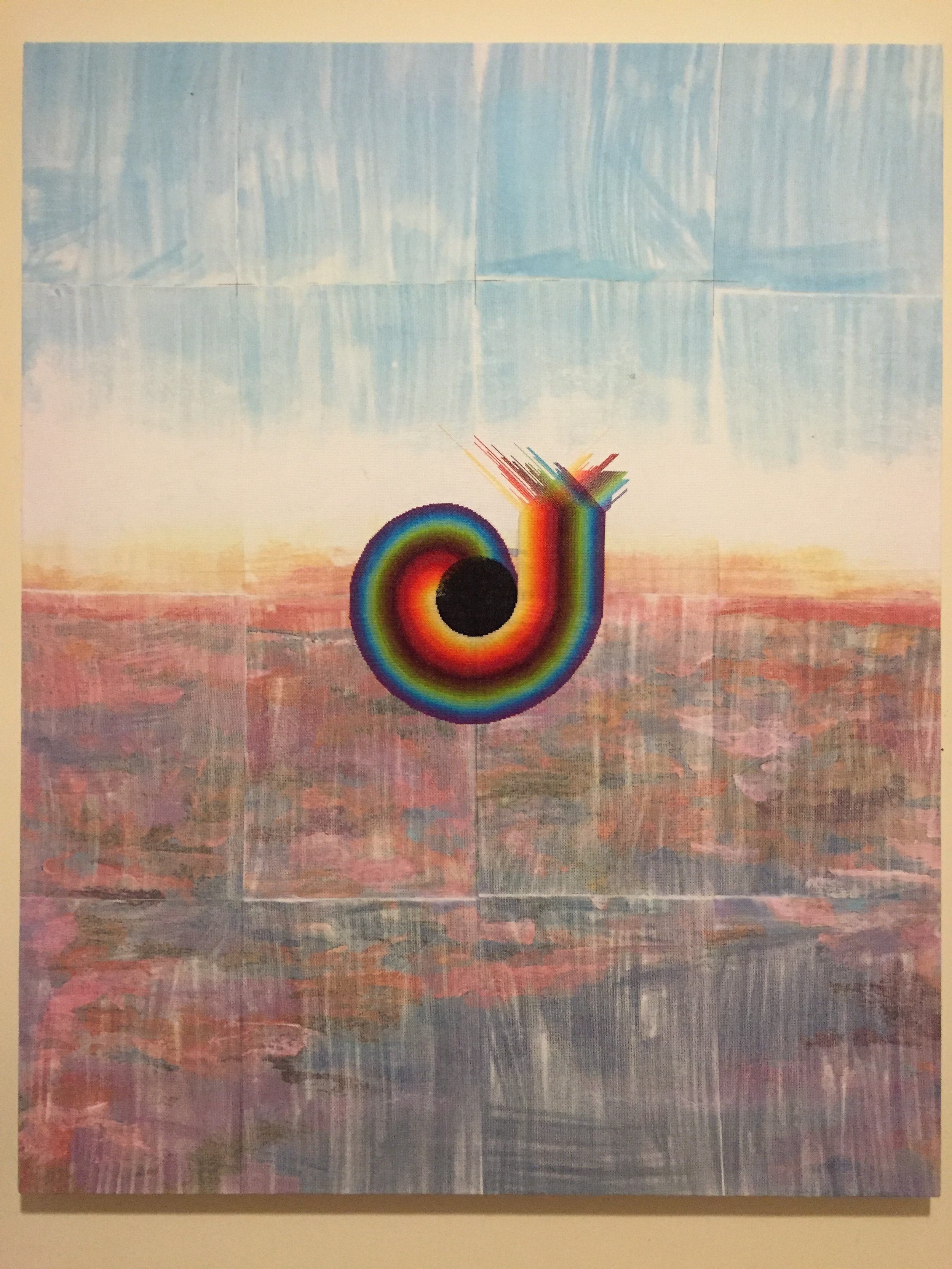

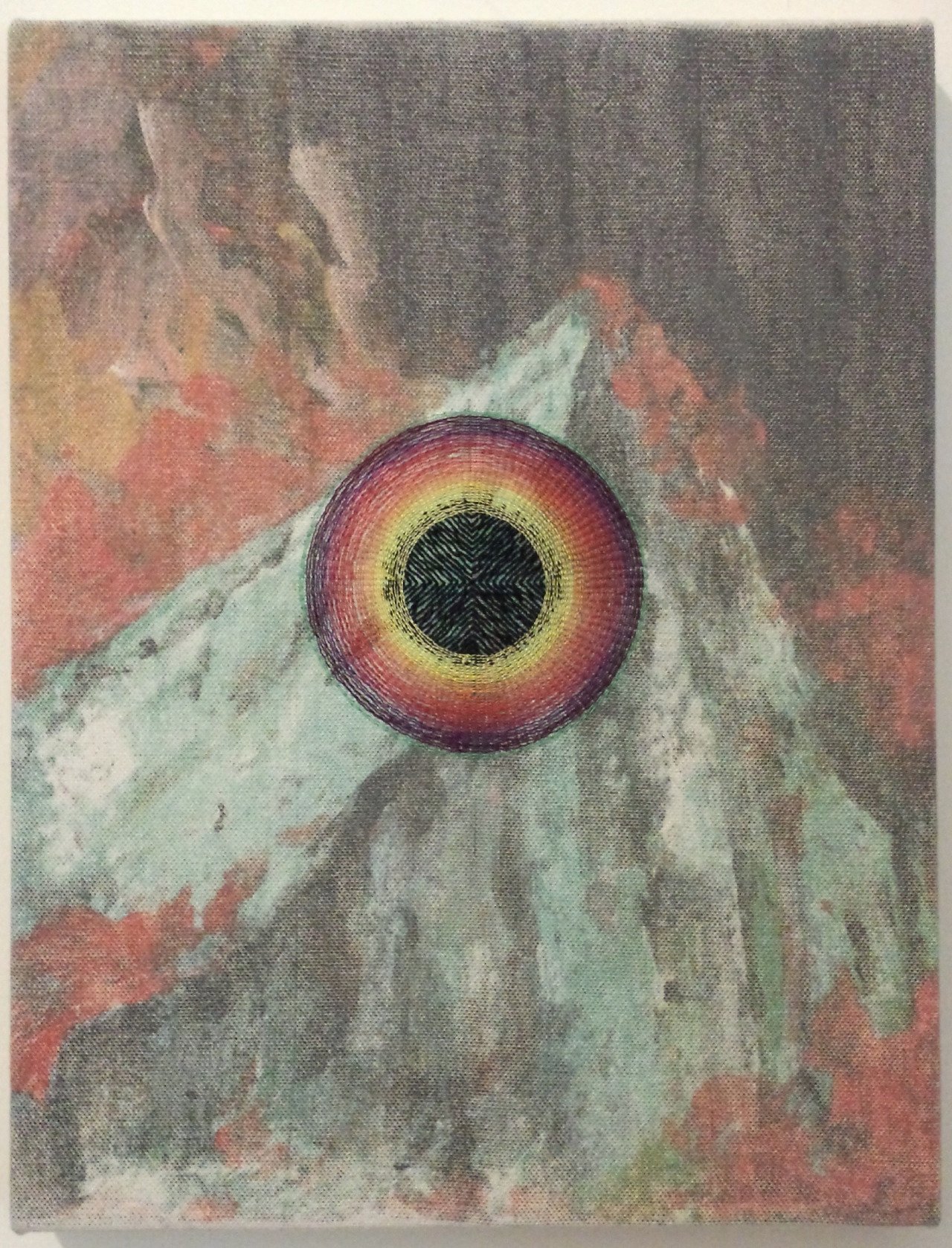

Pearl Cowan’s landscape and figurative paintings entice the viewer with their classical realism and masterful palette. Seductive flora and suggestive mushrooms allude to a hidden narrative lying beneath the surface of the paint, waiting to be penetrated by the discerning eye. The symmetrical lines and shapes that integrate the composition are oddly satisfying, like an alien language resonating on a primal level. Formerly an evangelical Christian, Cowan explores religious painting without the dogma, substituting geometry for Christ and void for presence. In the absence of a Savior, our devotion turns to nature, where we discover its sacred geometry from our privileged position at the center of the composition. As Cowan diverts our attention from Christ to the Radiant Void, we wonder if it is blasphemous, or if this is what religion has been trying to tell us all along. In her recent figurative paintings and drawings, Cowan comes out as a trans woman in a series of timeless narratives that unfold like so many Bible stories or Greek tragedies. A cursory reading speaks to the torture and suffering of these latter-day martyrs, but a more considered interpretation sees the humanity in their afflictions; indeed, they don’t seem to require intervention or sympathy. Like the iconic saints depicted in classical painting, they embody a transcendent calm that borders on rapture, and the Greek myths that Cowan often quotes are those with happy endings. The presumption of adversity is an ironic mirror that reflects our latent impulses, and Cowan taps into the depths of desire with compassion and wit. Her work is not intended as an apologia; rather, Cowan shares her experience with generosity and candor, using a classical medium to express nontraditional and queer subject matter. This juxtaposition, along with the humanity that emanates from her paintings, touches us at our deepest core, where we are neither male nor female, but a little of both.

MH: Your work is beautifully rendered, and it appears that you have a background in classical painting. What made you decide to go toward realism in your work?

PC: I was always drawn to realism and the Old Masters. I went to art school, but they don’t teach you how to paint, so for the most part I’m self-taught. When I was in New York I went to museums more than galleries, and my work was probably the most abstract that it’s ever been. Then when we moved to Boston, I spent a few intense years going back to the basics. I spent a year just drawing, then a year painting with watercolors, then during the pandemic I taught myself to paint with oils. I spent a lot of time online, watching YouTube videos on things like “How to Layer Paint”. It’s just in the last year or two that I’m able to do with paint what I want to do. I hesitate to say that I’ve mastered it, but I have enough control over the medium that I can have an idea and express it. It’s a new thing for me, being able to use paint in a way that I feel satisfied with.

MH: I’m inspired by your recent paintings where you scale up your small works. That’s hard to do, but you made it work in a powerful way.

PC: Yes, I wasn’t sure if my small paintings were going to scale up, and I was happy that it worked so well. That said, I still like to work small. The art world says that you have to make big paintings, which makes me want to work small. (haha) But I do like working large. They take a lot more work and a lot more resources, which has taken some adjustment. I had to scale up on everything: paint, brushes, palette, marks, storage.

MH: Your paintings and drawings are traditional in style but mysterious and sometimes challenging in content. It makes for an interesting juxtaposition, and I wondered if there’s intention behind this.

PC: Yes, I’ve studied academic painting and have learned a lot from these painters, but I want to speak to something more than painterly skill. Lately I’ve been painting about gender identity issues, so I’m taking a traditional visual language and adapting it to my reality. In that sense I’m pushing the medium somewhat.

MH: They could be called landscapes, but it seems as though you’re using the landscape as a vehicle to explore something more complex. Would you talk about that?

PC: With the landscape artists I’m drawn to in art history, it’s never just about the landscape. They give you beautiful scenery to look at, then there’s something more for those who want to look deeper. When I started painting the landscape, I was looking at the Last Judgment and wondering what it would look like without the figures. I was very religious for a long time, and this was at a time when I was leaving my church, so I was trying to communicate both the absence of faith and the desire for it.

MH: How did that show up in your landscape paintings?

PC: Leaving the faith was painful for me because it was something that I had really believed. It left a void, and in a very simplistic sense that’s what I was trying to express. The thought was, if you take the figure of Jesus out of this painting, what do you put in its place? And I was studying how artists constructed their paintings using geometry in the composition, so I put the geometry in instead of the figures. My thinking was that I wanted to paint religious paintings without the dogma.

MH: They totally embody that mystical feeling. Do you think the geometry transmits something even more profound than straight-up realism?

PC: Yes. The way the Old Masters painted religious scenery is very loaded and intentional; they place things where they do because it’s what they want us to see. Like, why do we think of God when we see a triangle? Why does geometry speak to us in that religious way? I’m not sure if I know the answer but it’s something that’s there, in classical as well as contemporary painting. It’s powerful, but I also became aware of a layer of manipulation. I went to Rome in 2018 and saw some of this art for the first time, and there was something profound about being in these incredibly beautiful cathedrals, but it felt like they were using persuasive advertising techniques to make me want to go to confession or become a Catholic.

MH: Haha! Reverse backsliding. How did this affect your work going forward?

PC: Among other things, it made me think about who I’m making my work for and who can afford to buy it. It’s out of reach for a lot of people, and I question whether I want to spend my life making trinkets for the wealthy. It’s one of the reasons I like to paint small, so more people can afford it and enjoy it in their lives. There’s something about the small scale that actively resists the commercialization of art. There’s only so much you can charge for a 5-inch painting!

MH: You did a series of embroidered paintings around 2013 that I was smitten with. They had craft references because of the embroidery, but they were also luminous like Renaissance paintings. What inspired that series?

PC: My mom died that year and most of the embroidered work was done after her death, using her sewing machine. I was thinking about her absence and about death, and I was in tears a lot of the time while I was making the work. I was also thinking about deferred dreams, because my mother told my wife that when she was young, she wanted to be an artist, but her parents wouldn’t let her. Which really surprised me because my mother never told me that, and she was always against me being an artist.

MH: We have a similar Christian background, which we’ve touched on in the past. How do your evangelical roots show up in your studio practice? Or have you thoroughly exorcised those demons?

PC: Haha! I don’t know if you can thoroughly exorcise them; I’ve certainly tried! For a long time I was very bashful about using religious themes in my work, but I finally got to the point where it felt okay to be open about that part of my life. It’s a true part of me and if I want to make art authentically, I need to own it.

MH: Your newest work is about the trans experience. What inspired this amazing body of work?

PC: Well, being trans was a big inspiration! There was a big shift in my work in the beginning of the year, from painting landscapes and flowers to figurative work. I wasn’t exactly hiding with my previous work, but it was more like I was encoding it, and with the figurative work I can be more explicit. Last year I came out fully and it’s been rejuvenating, so there’s something about being more open and authentic about who I am that’s reflected in my work.

MH: Yes, I was wondering if your work feels more authentic as a trans woman than when you identified as male? Do you see a difference in your work?

PC: Yes. I was recently looking at a portfolio of work from 2006. I was 23, I’d just moved to New York, just graduated from college, just gotten married to Vanessa, and the work I was making was so queer! Looking at this stuff now it’s like, how did anyone look at this and think I was a straight man? I don’t think I would have said it like this back then because I was deep in the closet, but the landscape work was an attempt to suppress the queer aspects of my work and to suppress it in myself. There’s a lot more authenticity now. I don’t think the work I was making then was necessarily good, but it speaks to the power of art, that it knew who I was before I did.

MH: So your art is a little bit ahead of you!

PC: Yes, and looking at that work gave me the courage to make what I’m making right now. If I’d been more tuned in to what I was doing back then, I probably would have come out a lot sooner. Artists learn about themselves by making things – abstract painters, conceptual artists, hard edge painters, there’s always something of them in their work. You can’t really get yourself out of your work.

MH: The trans women that you’ve depicted often appear as so many saints and martyrs in classical painting, and I’d love to hear you talk about this aspect of your work. I can imagine that trans women experience this kind of persecution in their lives.

PC: Yes, definitely. Those stories of saints and martyrs speak to very human struggles, and for trans people, that’s all part of it. There’s something deeply human in those stories that repeat themselves in every culture. But I don’t want to make it just about suffering; I’ve tried to be ambiguous about whether the person is enjoying what’s happening to them. There’s pleasure, there’s pain, and there’s the ecstasy of pain. Those connections are there for me now but if you talk to me in 20 years, I may say something entirely different.

MH: Our country is going through a painful time, where a large portion of the population wants to expand into greater open-mindedness, while a small group wants to contract and return to the “good ol’ days”. How do you see this transition? Is it a temporary state, or the initial stages of a permanent split?

PC: I hope the former but fear the latter. There’s a group of people who’ve always been in power, and they don’t want to share their power or give it up. Going back to the good old days means that they want to go back to when the world was focused on them. But most people are open to diversity, so I don’t think there’s going to be a permanent split. Young people are very open-minded, and they know that it’s a better way to live, to embrace differences and let go of the toxic beliefs about superiority. In my own experience, the majority of my friends and acquaintances were supportive of me coming out.

MH: It’s a slow grind when these tectonic shifts happen in a culture, but do you think that over time our society recalibrates and embraces each other’s differences?

PC: I think so. I’m an optimist, but I’m also a realist. The threat is real, and the pushback that’s happening with conservative white men is a real problem. But the way the world is now, with access to so much information, I don’t think the cruelty is going to last. Like with overturning Roe, we see women dying again and it’s tragic. People don’t want this to happen to themselves or to the people they love, so I don’t think that it can be suppressed for long.

MH: What role does art play in the process of normalizing a taboo?

PC: I think art is humanizing. It creates empathy, and it’s a way for people to feel connected. You look at a painting from hundreds of years ago and you can relate. Or you read a book that has characters who are gay or trans, and you realize that they’re just as human as you are. That’s why they ban certain books, because they don’t want kids reading about someone who identifies differently than they do and find out that they’re just like everyone else.

MH: It’s interesting that you have the benefit of approaching your work from both a masculine and feminine perspective. Is there a notable difference or is it all coming from the same well of creative expression?

PC: My work has always been a bit feminine, and I embraced that side of me in artmaking long before I embraced it in life. I feel like I’m catching up to where my art has been for a long time.

MH: What’s the best part about being an artist?

PC: My favorite thing is community. I’ve met so many great people through being an artist. I like making work that people connect to, and I’m always excited to hear what people have to say about the work and how it connects to them or doesn’t. As artists we make these things and hope that it has impact, and having people reflect that back is always so moving to me.

www.pearlcowanart.com

Pearl Cowan: Metamorphosis is on view at LABspace in Hillsdale, NY through April 28. On view Saturdays + Sundays 1-5:00.

Pearl Cowan will be in conversation at LABspace with Jacqueline Cedar of Good Naked, Sunday, April 28 at 2:00 p.m.