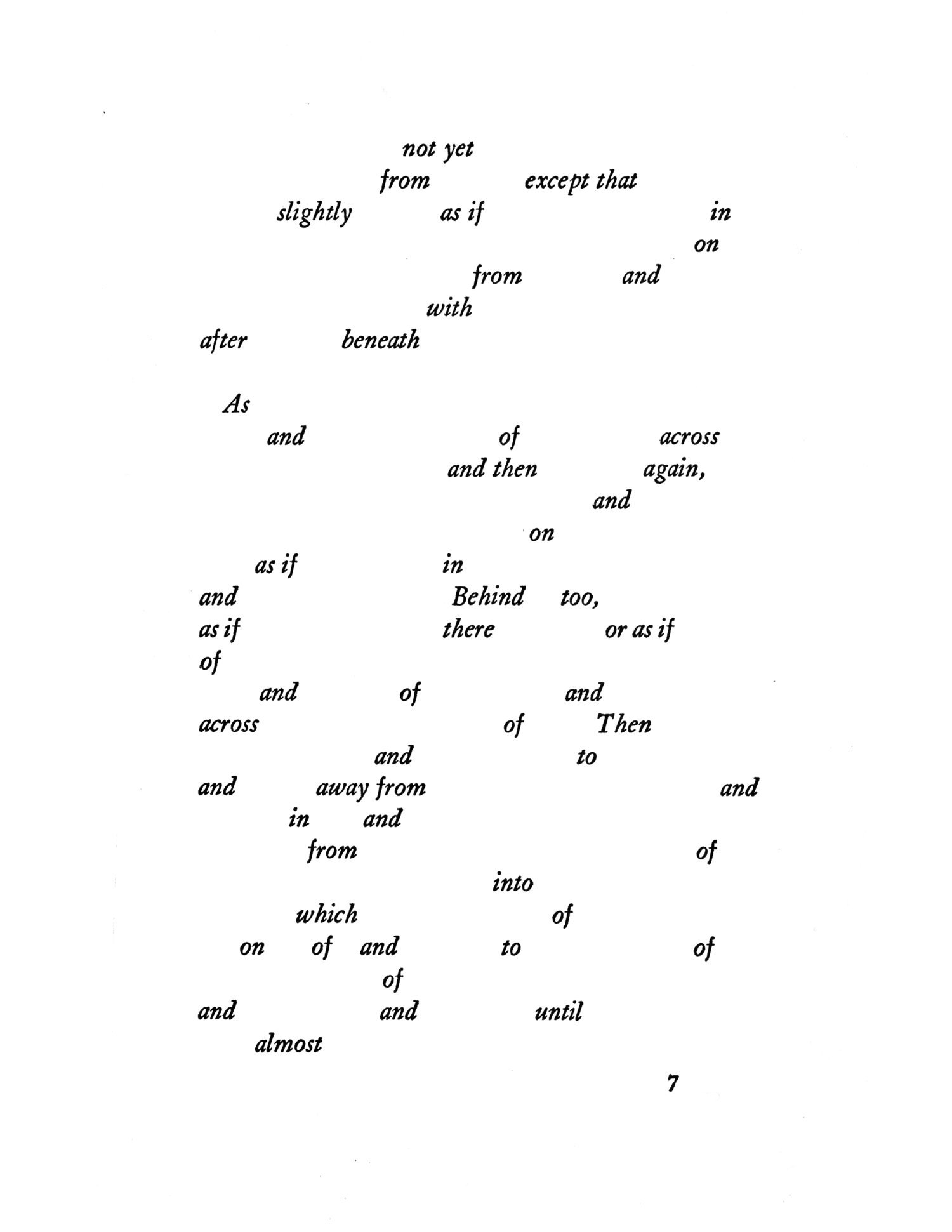

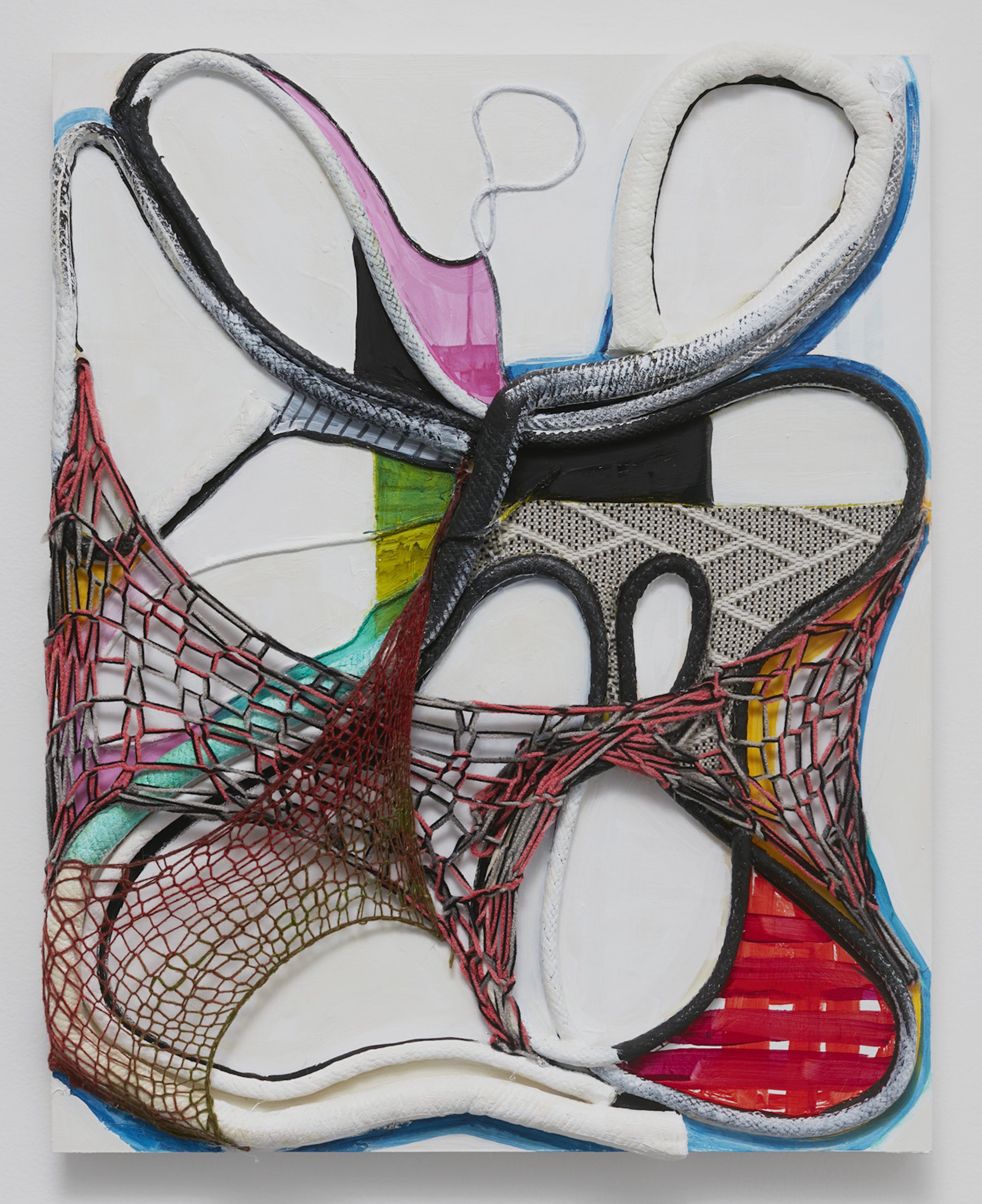

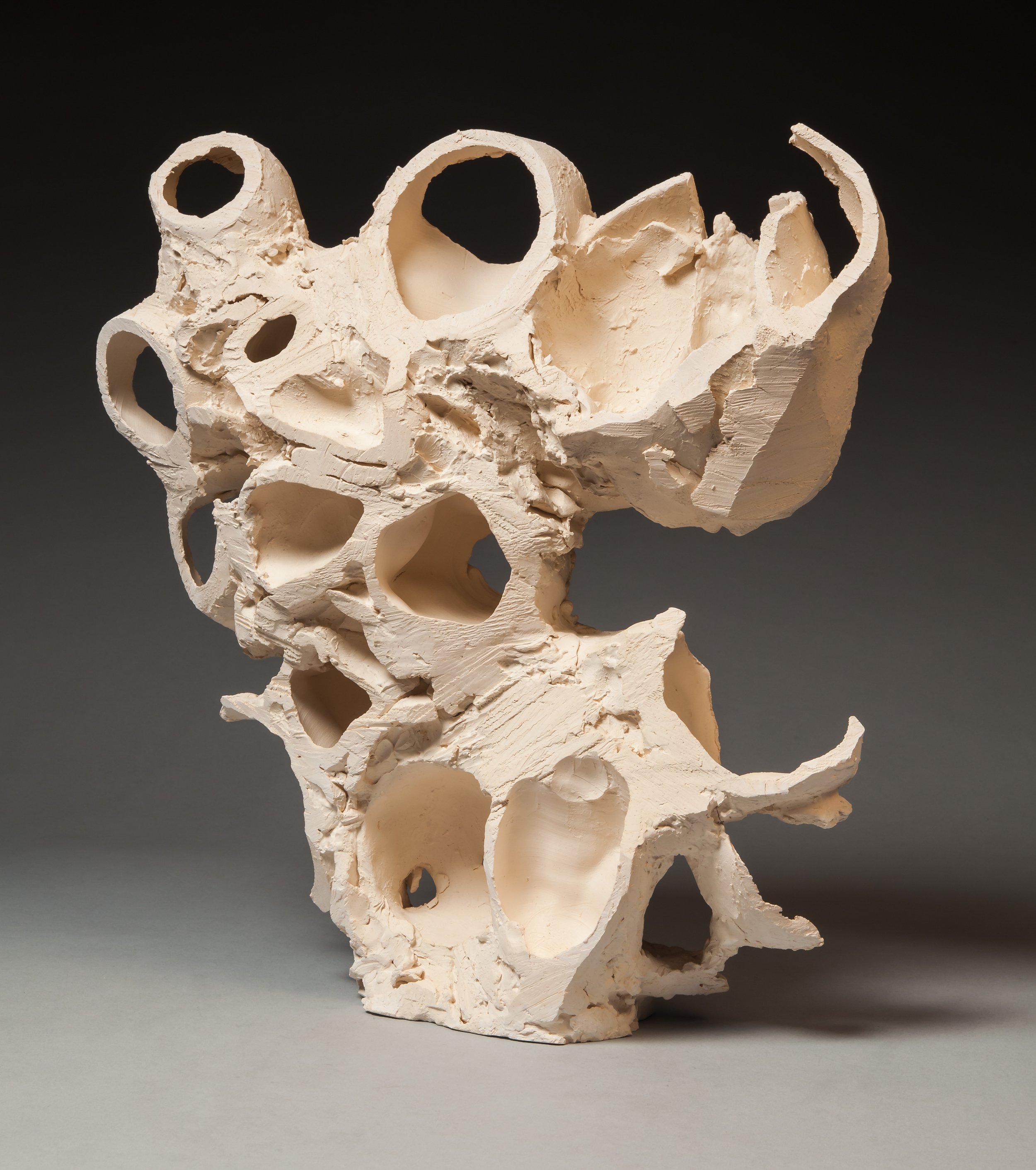

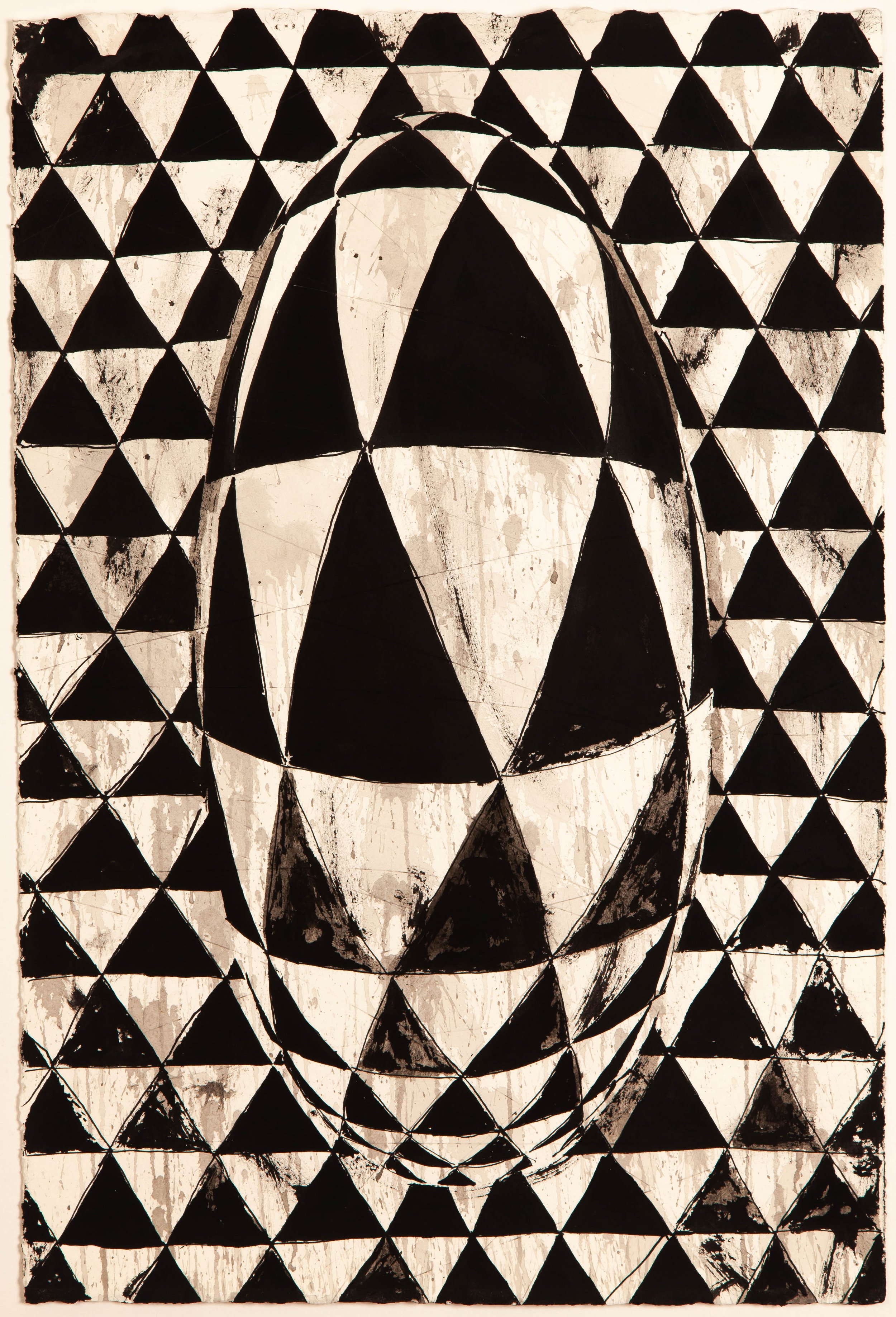

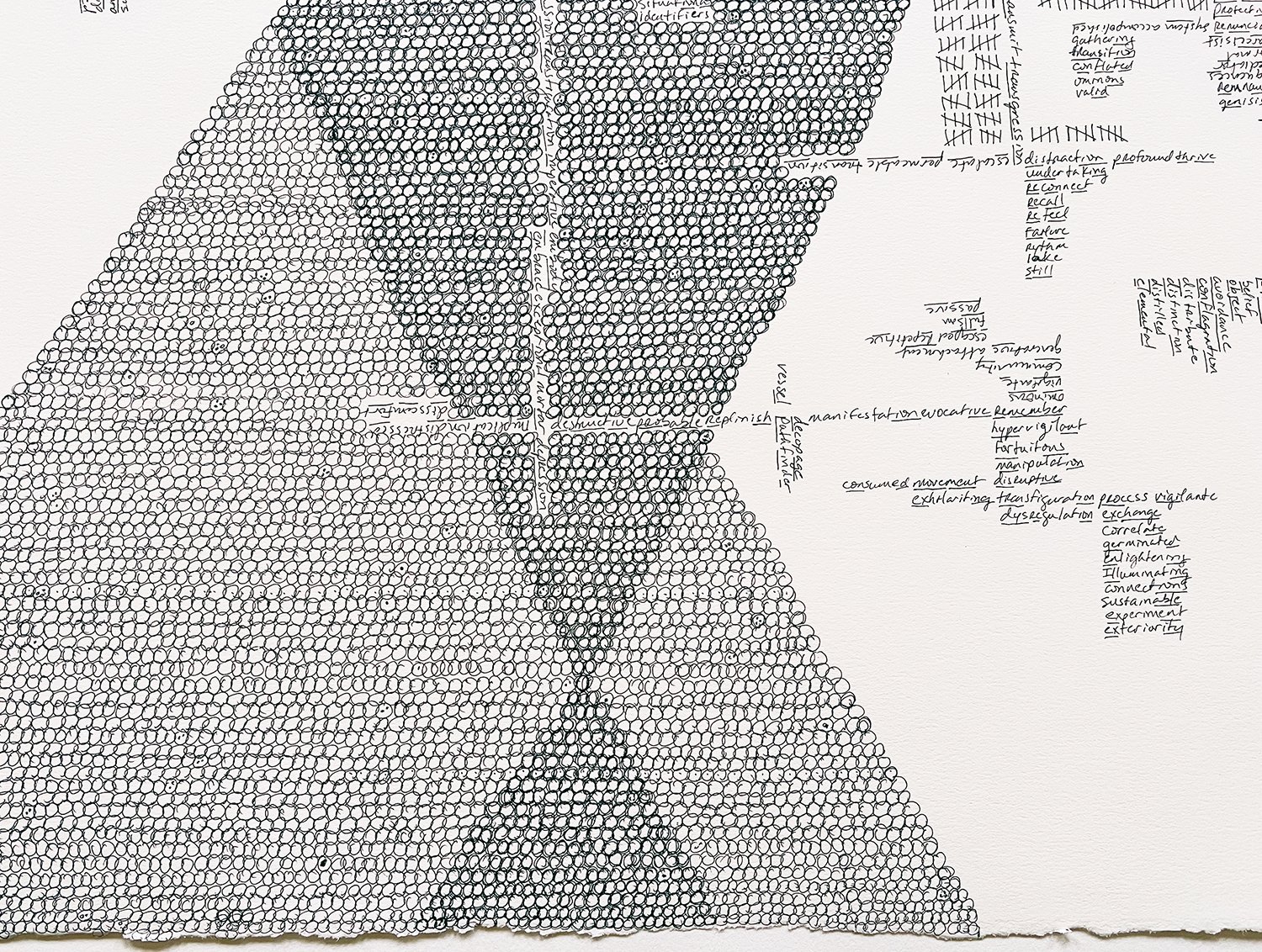

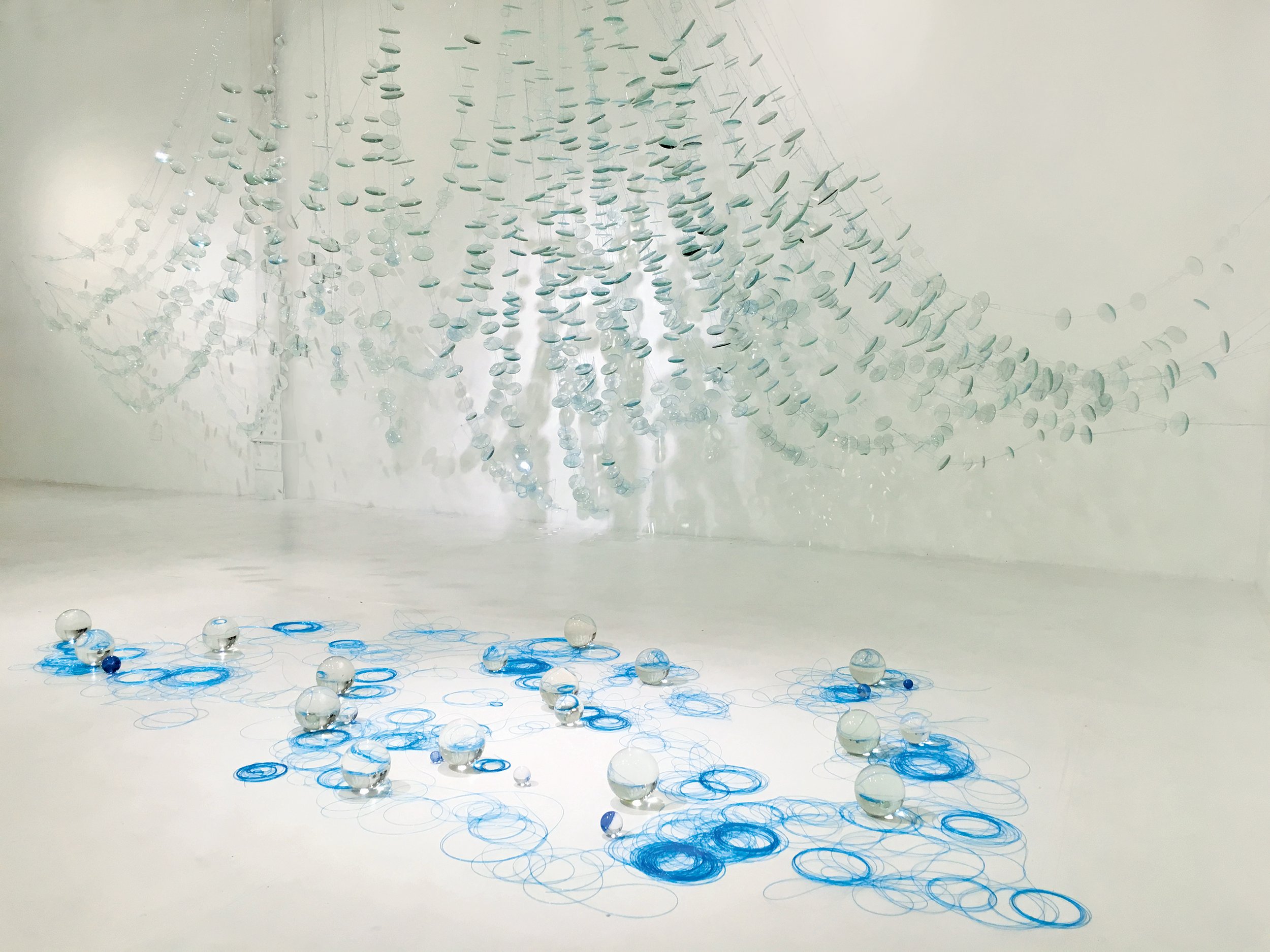

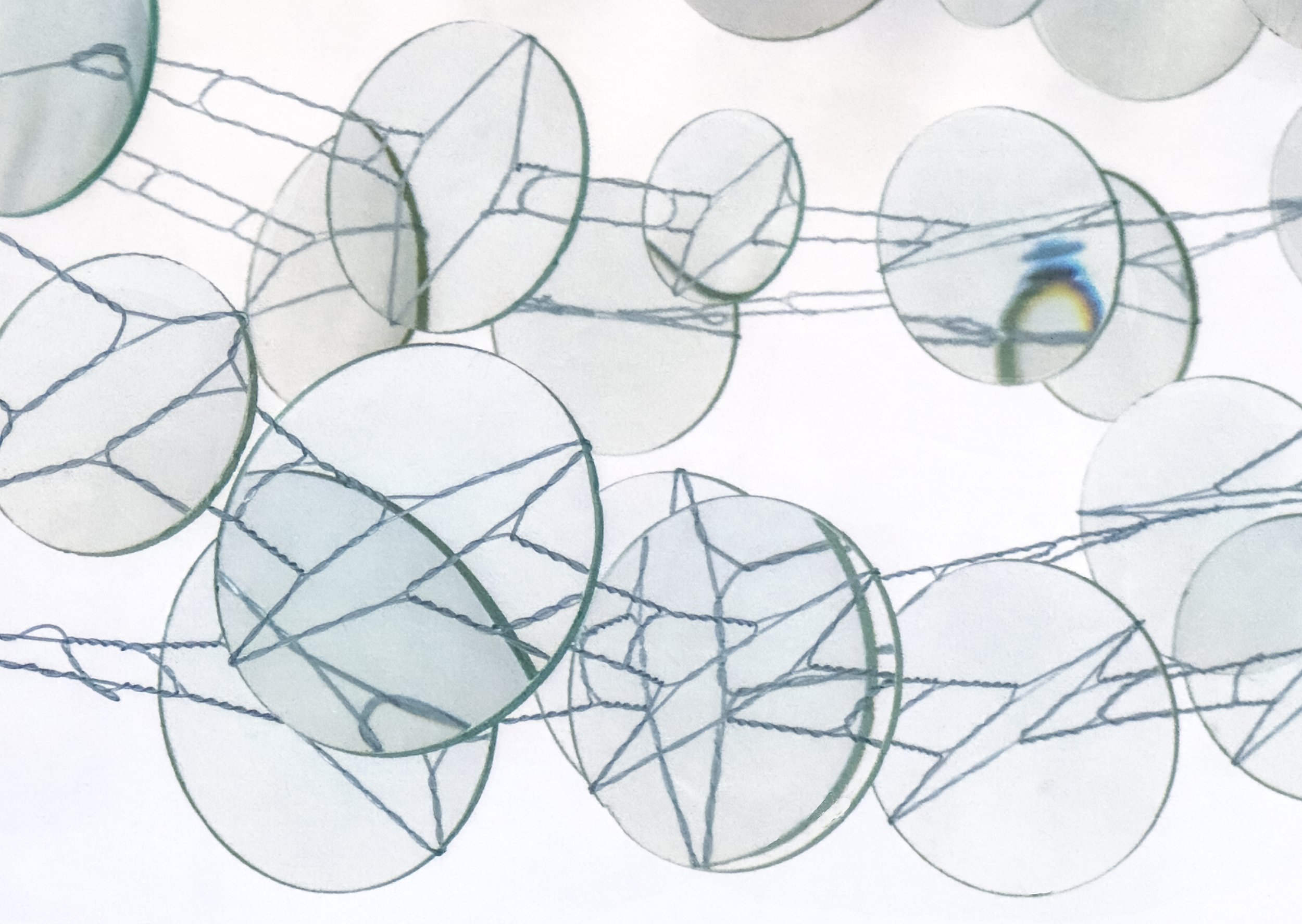

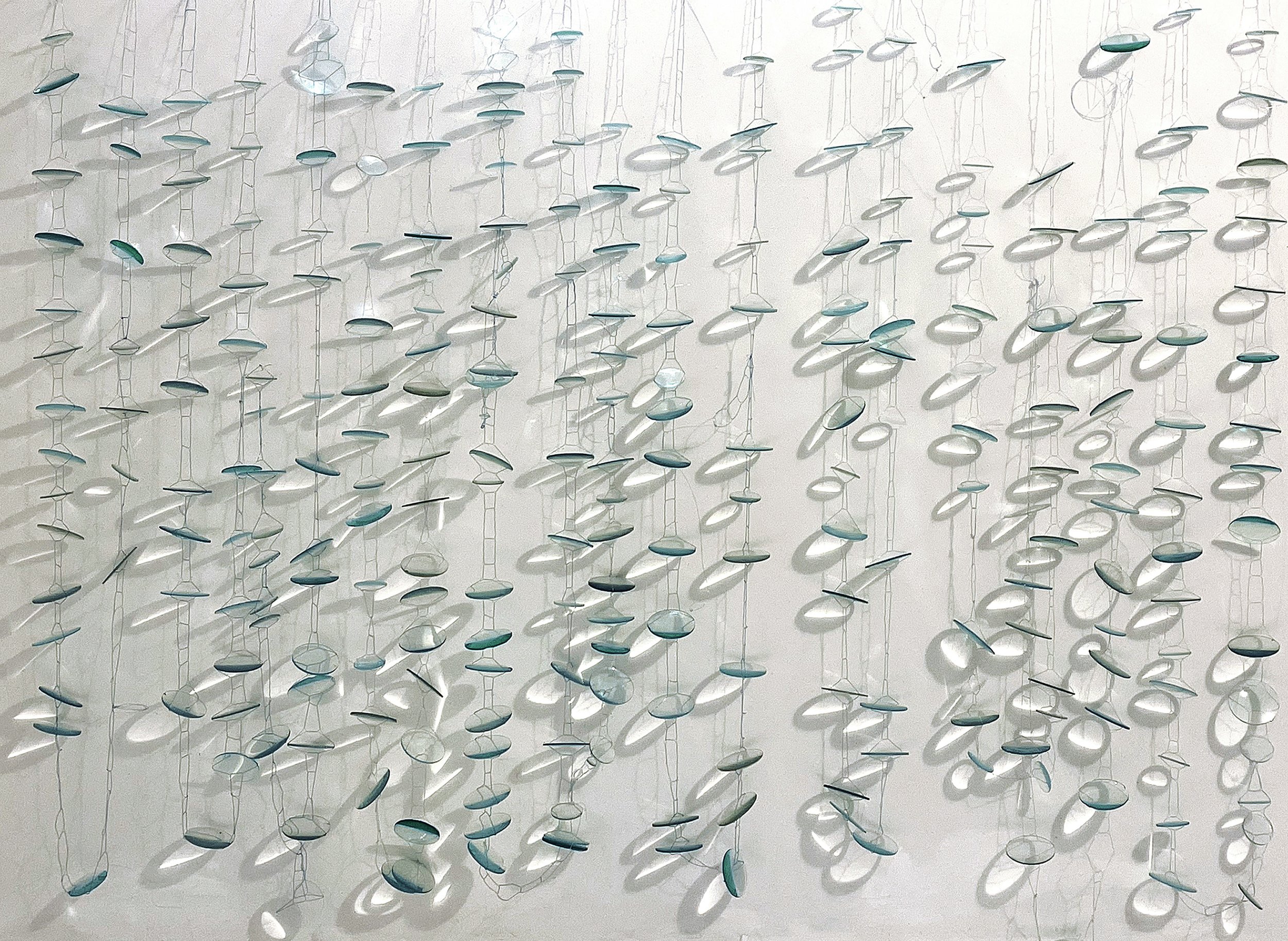

Audra Wolowiec is a New York-based artist whose work is centered around language, sound, and breath. Her work spans many disciplines – installation, print, sculpture, performance – and speaks to the human body and the space it inhabits. She explores the body as a container for sound, and many of her performances play with the idiosyncrasies of language, with its plosive consonants and feathery fricatives. Wolowiec grew up with a stutter and describes how as a child she struggled to push awkward letter combinations out of her mouth. She experienced stuck words as physical blocks and was able to “see” these sounds as dense forms in her body. Her years of various speech therapies led her into the back rooms of the spoken language, where slippery syllables are exchanged for stock words that are more easily enunciated. These lessons in word substitution and speech fluidity gave Wolowiec a familiarity with language that few of us will ever have, and this intimacy can be seen, heard, and felt in all her work. The arrhythmic cadence of a spoken passage, the exhalation of commas extracted from the U.S. Constitution, a text by Virginia Woolf distilled into a sound score and performed by vocalists on a ferry crossing – these are just some of the compositions that bear the mark of Wolowiec’s affinity for language and poetic expression. Her sculptures and works on paper are similarly layered with linguistic allusion and may be best described as tactile poetry. They are quiet and unassuming, possessing the grace and gravitas that express the essence of our humanity. Indeed, there is a thread of vulnerability that weaves through all of Wolowiec’s work, perhaps a remnant of the dysfluent speech that she painstakingly learned to modulate. Through her work we also become attuned to the fragility of the breath, and by extension, the tenuous nature of our existence. We are communal creatures who depend on social intercourse, and our intentions are conveyed in the interstices between utterance and breath.

MH: Your work crosses several disciplines – installation, print, sculpture, performance – and is centered around language and sound. How did you arrive at this mode of expression?

AW: I’ve always been interested in tactility, the body, and spaces that the body inhabits, and sculpture seemed like a good umbrella to cover all those things. When I lived in Detroit, I worked in a production pottery shop where I learned how to make molds and the process of casting, and this led me to grad school at the Rhode Island School of Design to study sculpture. Through trial and error I began to delve further into my experience with speech and language. As a person who has had a stutter my whole life, I have a very different understanding of speech, the voice, and what it’s like to have words held inside one’s body.

MH: How did overcoming a stutter contribute to your interest in speech, sound, and the flow of language?

AW: I’ve gone through various speech therapies and read a lot about speech dysfluency. In my work, I started playing with ideas of voice and speech as tactile materials. In terms of my personal experience with dysfluency, what was produced was a lot of social anxiety. It’s something that I hid for so long and tried to avoid talking about, because there was so little conversation around it when I was a kid. It was hard to say my last name, and I had such trouble speaking that I just didn’t talk in class at all.

MH: I suppose the shadow side of speech therapy, or any kind of corrective therapy, is the underlying message that says you’re not okay as you are. How do you walk that fine line?

AW: It’s very tricky. I hated speech therapy when I was a kid. I felt like I was always doing it wrong. We grew up in a time where we had to hide so much about ourselves, and we weren’t able to just be in our bodies the way they are. As a teacher now, I’m conscious of nuanced approaches to communication, and I avoid the things that I had anxiety about when I was in a classroom setting.

MH: Have you heard of JJJJJerome Ellis? I love their work! They’re an artist, musician, and composer whose dysfluency informs their work. I love that they spell their name the way they pronounce it.

AW: Yes, I’ve met them – they’re wonderful! They’ve done some work with Dysfluent Magazine based in the UK that I’ve been involved with, and they did a billboard for the Whitney Biennial, which Jerome was in. They work with other advocacy groups and invited SPACE to stutter to create a pop-up exhibition during the biennial that I contributed to, bringing awareness, acceptance, and visibility especially for younger people. The poet Jordan Scott also comes to mind. He wrote a beautiful, tender book about stuttering called I Talk Like a River.

MH: Language is a physical, tactile, and visual experience for you. Would you talk about that?

AW: There’s so much about the body that goes into speaking for me – breath, slowing down, being centered – and there’s also a playful quality that comes from my slipperiness with speaking. Like if I’m trying to say a word that isn’t coming out, I experience it as a physical block, so I’ve learned to switch to another word, or try a different pace or cadence. Some letter combinations are very hard for me to say, so I’ve learned to substitute or elongate certain words or syllables. It becomes very visual and tactile for me.

MH: I’m quoting you here: “It’s alarming how much stuttering makes other people uncomfortable. Through the sound scores and performances, I’m interested in challenging that discomfort, playing with it, and making it tactile.” Would you explain some of the ways that you bring dysfluency into your work?

AW: A specific work comes to mind, a sound installation called Power Talk. It’s from a self-help book about speaking with influence, power, and command, and it lists the words that you should include in your speech. They’re very strong words with plosive beginnings, and I thought, what if the power was not in the vocal commands, but in vulnerability? So I took the list of power words from the text, then extracted all the sounds that are considered powerful, like the hard P’s an T’s. It was a very awkward series of sounds that I thought could invite a listener into an intimate space with another person’s voice. I had the recording on various speakers at Present Company in Brooklyn, and the speakers were embedded in the drywall, so you walked through this narrow corridor where you’re aware of your body and the space that it takes up. I was l hoping to invite a kind of intimacy.

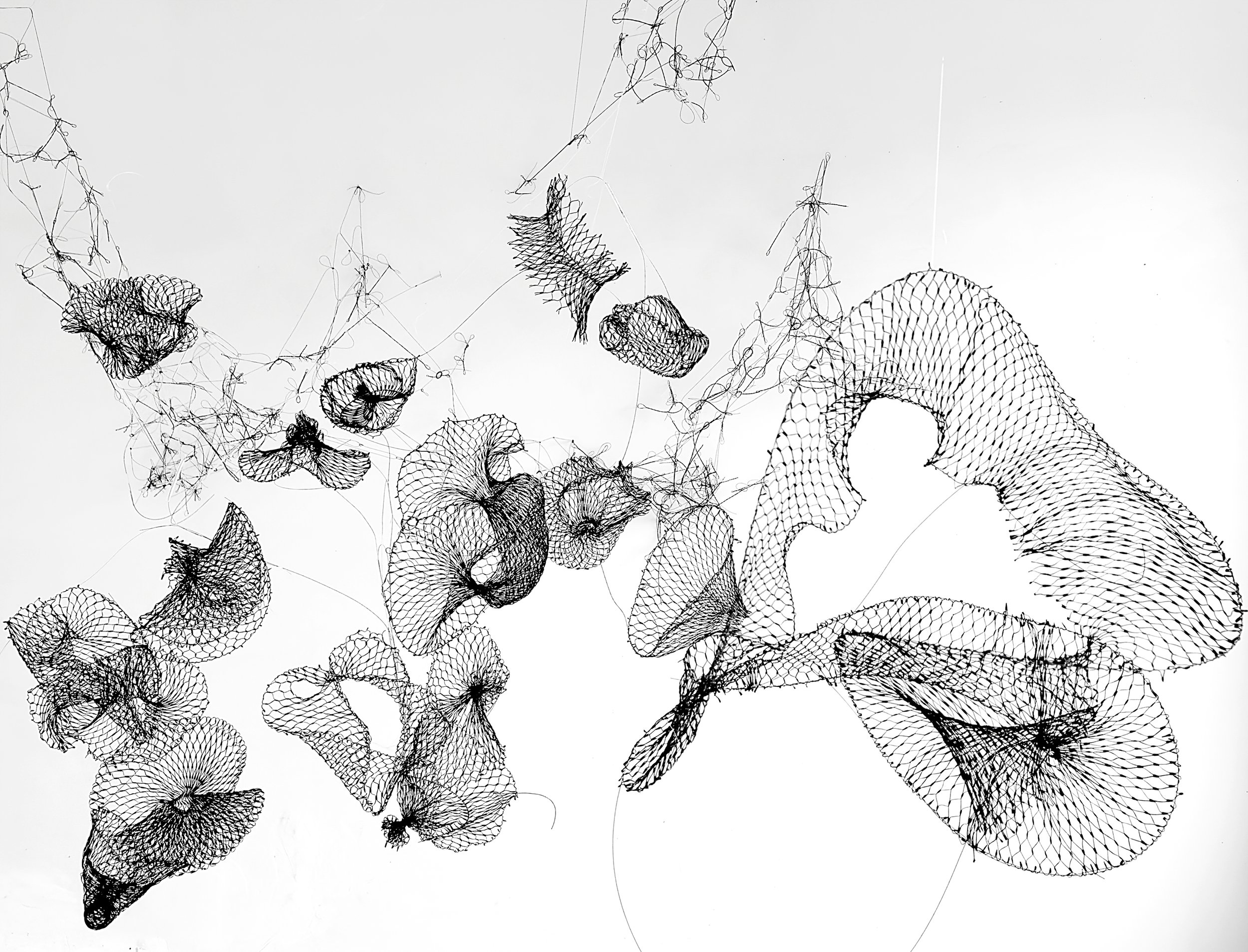

Breathing Room, 2012. Plastic bags, thread, wood, tape, air

Site specific installation using natural airflow into and out of a room. attention is placed on one's own breath as the architecture itself begins to breathe. Shown at Studio10, Brooklyn.

MH: Your work addresses not only speech, but the silence between the spoken words. It’s as if you’re more interested in the space between words than the words themselves. How do you regard this space, and how do you relate it to breath and the comma?

AW: In music notation, the comma is the mark for the performer to take a breath. There’s an analogy between the comma as a sign to take a breath in a performance, and the comma to take a pause in a sentence; both are very charged spaces. So my use of the comma came through wanting to address the breath in an existing text in the same way that I played with language. There’s a lot of interplay between the cadence that comes out between those pauses or gaps that’s often interpreted as an absence, but I think of it as a very rich and generative place to work from and sit inside.

MH: If humanity can be expressed through something as ephemeral as breath, then we might expect it to be present in a brushstroke, a single note of a symphony, a solitary vowel in a poem. Does your isolation and repetition of letters and sounds allude to this in some way?

AW: My hope is that it creates the space for that, and a space of listening and connection. When breath becomes an intentional act, then it brings attention to being present. I think what you’re talking about happens most often with performative art, when these daily repetitions become central. The work of Pina Bausch comes to mind, or the work of Tehching Hsieh.

MH: In your piece AIR, you erased all the letters and punctuation in the U.S. Constitution except for the commas. Quoting you again: “(I was) thinking about the Constitution as a document of the people, how it’s supposed to stand for our rights, but it’s so often used against people. What is the most human element in it? I thought it was the breath. It’s something that we all have, something that’s been taken away or contested. The commas are the breath emerging from the Constitution.” In this context do you see the commas (and breath) as inherently subversive?

AW: I think it’s subversive in our political climate, where certain people are allowed to breathe and others aren’t, and where some breaths are taken away in a violent manner. Breath is something that every person does naturally; it’s a way of communicating and of calming one’s body. There’s a lot of privilege in not thinking about breath, so drawing attention to it was important to me.

MH: That’s interesting. So when you breathe, you’re basically saying I’m here. And if your existence makes another person uncomfortable, like if you’re an immigrant or trans or dysfluent, your very breath can be seen as subversive or confrontational.

AW: Yes, and breath is so intimate. We don’t listen to each other breathe – it’s uncomfortable, maybe even a little creepy. Breath is incredibly nuanced and has a direct relationship to rights and access, as well as the ideas of power and belonging.

Recording of an excerpt from AIR: ”The sound installation and notational score was created from extracting the commas from the Constitution of the United States of America. In music notation, the comma is the mark for a performer to take a breath. I invited breath practitioners from various fields—singers, actors, yoga and Lamaze instructors—to translate and interpret these pages of commas through their individual training and practice of breathing. I was interested in how the commas in writing are analogous to commas used for breath marks in music, and how an intimate and vulnerable exchange could emerge from this politicized text, extending beyond the boundaries of language, into an embodied and intimate human experience.”

(from the artist’s website)

MH: This piece about the Constitution, AIR, is apropos to our current political climate, where we’re holding our breath, as it were, to see what comes next. Do you ever regard breath and breathing as an act of independence, even patriotism? Or is it entirely human, without political or religious overlays?

AW: Breath is the one part of our voice and existence where we can sit in front of each other and breathe and listen without knowing each other’s language or beliefs. It’s the thread of empathy, the space to see another person, and it’s a communicative sound without speech or language.

MH: In the presence of censorship and the absence of creative freedom, all that’s left is the soul of the work: its breath. Do you have faith that our humanity could be conveyed in a work of art, even in the face of profound oppression?

AW: I think art in its many forms teaches us about humanity. It allows a sense of the collective, a way of understanding things outside ourselves, and when it works, it’s deeply empathic. In terms of profound oppression, I think imagination gives a sense of hope, something to hold onto. But then it becomes something different than self-expression. It’s no longer the solitary artist or writer expressing herself, but a lifeline that allows people to transcend their situation and to imagine a way forward, a future one can exist in.

MH: In a perverse but advantageous way, oppression and censorship may transform artwork from innocuous paintings to subversive agents of rebellion. A simple landscape or abstract painting might become a beacon of humanity when hanging on the walls of a corporate headquarters. Do you think art has the power to pierce through the disinformation and change minds?

AW: Definitely. It’s important that we read and look at the works of people who are under assault and in exile, for example, Palestinian writers and poets. There is such a lack of empathy in our society, and it makes a difference to understand human, lived experiences. I do think that art and writing can do this, and if not directly, then as an entry point.

MH: So oppression and censorship almost amplifies what the artist has to say.

AW: It highlights it if it’s brought into public view. How would we know of the many silences? I’m thinking of the banning of books, which is happening all over the country. Someone gets to decide what books are allowed and not allowed. It’s quite shocking what’s considered off limits, and that should tell us about the structures at play. In terms of art, I encountered a situation recently where an artist’s performance was censored because it was deemed to make certain people uncomfortable. When something is censored, and when that censorship is brought forward into public attention, it potentially has more voice. Censorship is designed to silence, but also as a way to exhaust; one has to go up against it.

MH: If hope has been gutted, what do we as artists have to express? Does one’s work become nostalgic, as in a pining for freedom, or do we carry the torch for the next generation?

AW: After the election there’s been a lot of commentary about freedom, democracy, and the idea of hope. I think we have to consider what we do have, and how we can work together. Perhaps courage is a better word? The idea of nostalgia is tricky because in many cases, there’s even less equality in the past. There’s a lot of privilege that comes with nostalgia, and for many people, nostalgia becomes oppressive.

MH: Absolutely. That’s what the whole MAGA movement is about – nostalgia for a time when white men held all the power. So the question becomes, nostalgia for what?

AW: And for whom. James Baldwin has written a lot about this.

MH: On a less apocalyptic note, your work with language is deeply poetic, engaging our senses on many levels. In a recent piece, (waves), you had five vocalists (sirens) perform a spoken word piece on a ferry crossing, and after the ferry reached the further shore, you placed words made of ice into the Hudson River. A gaggle of passengers and geese gathered to witness the ice words slowly melt until they were subsumed into the river. This feels entirely mythological! Did you place coins in the passengers’ mouths?

AW: (haha!) Yes, that was what I was hoping to conjure – the experience of water, of human passage, movement, migration – all these things were there. That was one of the prompts for the performers – to locate their own experience of water as a character, a place to speak or sing from. In my own speaking and in dysfluent speech, there are a lot of analogies to fluidity, fluency, and smoothing speech. With the ice, I was thinking of something solid like a block of ice with its hard edges, and then to have those edges smooth and dissipate as they melt in the water. It may be mythological, but it’s also a metaphor for speaking, both the physical and the ephemeral nature of words and language.

MH: Does your work sometimes feel mythological, as if you’re expressing something larger than the time in which we’re living?

AW: Maybe, but I don’t know if I consciously think about that. I’m really interested in collaboration, so maybe that comes into it – wanting to bring other voices in and not be the sole author of a piece. I like the idea of interpretation, of inviting people to respond and to add their voices into the mix. It’s a way to think about the collective or the human experience that is outside of my own experience.

MH: You spend a lot of time with literary works, thinking about their content and surgically excising their letters. As you deconstruct these texts, is there a common language that slowly reveals itself to you? Not in a literal sense, but a silent expression of our shared human values?

AW: It’s specific to the individual work. I’m interested in the title of the book, what the author is saying, and how they’re writing. I try to distill or extract an aspect of what the author was trying to express, and these are books that I’ve had on my shelf for a long time, so I’m very familiar with them. So when I worked with The Waves of Virginia Woolf, it wasn’t the whole book, but these interstitial, italicized chapters that talked about the weather and the qualities of the ocean. I worked with it by pulling words to the surface and being in conversation with the text, like what is the most wave-like, slippery, buoyant aspect of the text? I often think about it as a process of mining.

MH: Other than the desire to communicate with our fellow humans, what do you think artists hold most dear?

AW: Artists question the status quo, and they often don’t conform to what other people are doing. When you’re a young artist, living outside the mainstream is a lot easier. Things like housing and having good healthcare may not be accessible, so there’s a marginal aspect to being an artist, especially in the United States. Artists invite a slower read of the world, and often shape their lives around it.

MH: What’s the best part about being an artist?

AW: Talking to other artists. Being in conversation with other creative people. A sense of possibility.

www.audrawolowiec.com

Thanks for reading my Conversation with Artists!

It’s a labor of love, and I sincerely appreciate your year-end donations.