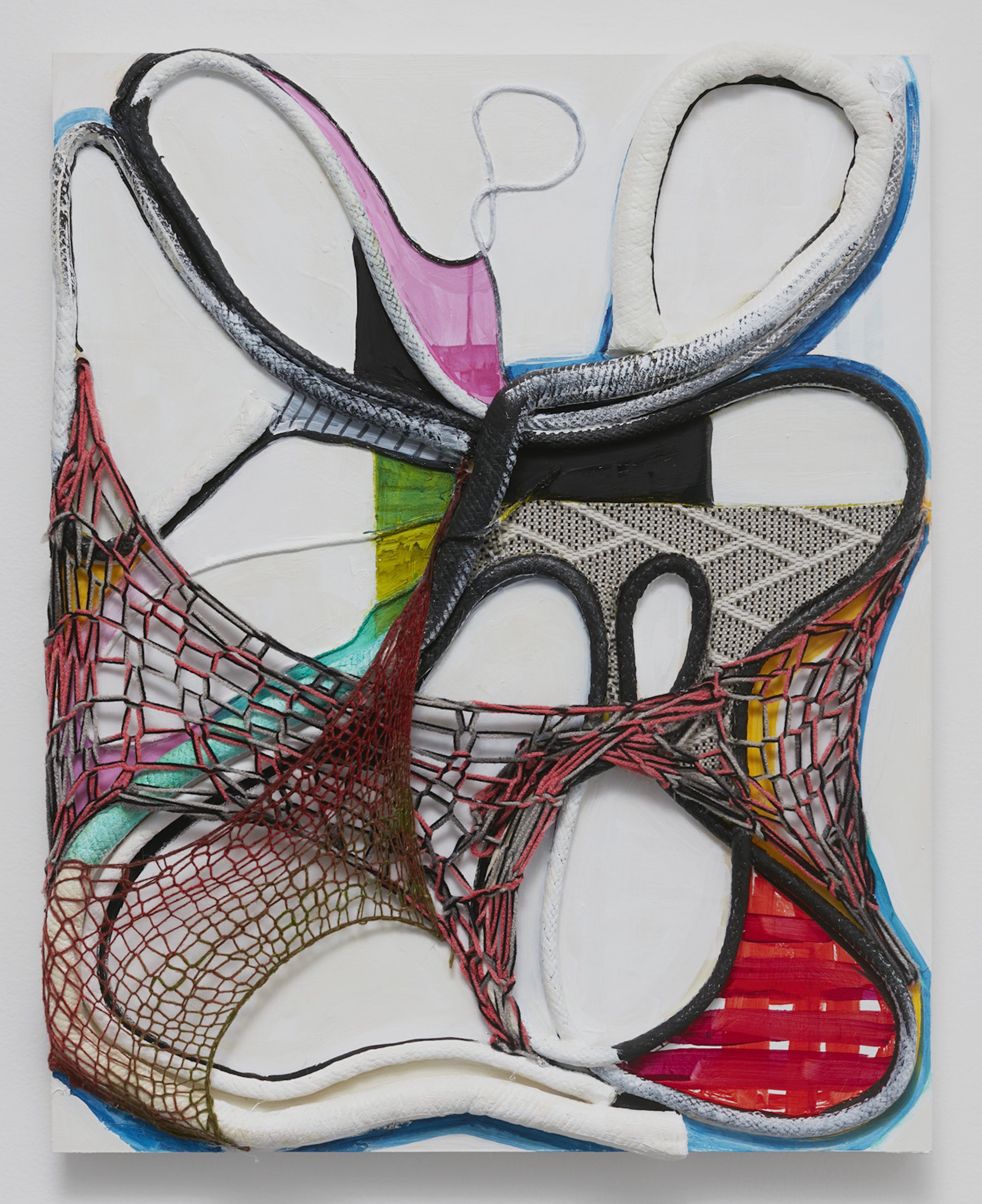

Susan Mastrangelo is a figurative painter, but not in the traditional sense. There are no facial features or fleshy limbs to entice the viewer; no nostrils or nipples thrown in to suggest anatomy or skin. Mastrangelo’s interest in figure drawing began to wane a decade ago, when her focus shifted from the external form to how it felt to be inside the body, among its organs, sinews, and coiling viscera. Her medium expanded when she began using materials found in fabric stores, gluing industrial upholstery cord and scraps of fabric to wooden panels. Mastrangelo “draws” with the thick cord, outlining large areas that she fills in with paint, textiles, and fragments of yarn. Her process is deeply intuitive, as she relies on natural impulses and decades of figurative work to express that which is hidden in the recesses of the human form. In the final stage of her process, Mastrangelo connects the various sections with loose sheaths of knitting that she stitches in synchrony with the body’s natural rhythms. Indeed, when she knits for extended periods, the repetitive stitching begins to align with her heartbeat and breath; it becomes the tissue that repairs, heals, and connects her with the painting. This is the soul of the artist’s work, where she projects herself into the painting through her materials, focus, and sheer labor. By dissecting the figure, Mastrangelo exposes its concealed cavities with their vital organs and tortuous piping, the essential fabric of our physical form. Mastrangelo’s relief paintings transcend the individual, directing our attention to the biomorphic structures that sustain us and make us human.

MH: As a child you explored a variety of creative expressions, including the clarinet. What made you settle on the visual arts?

SM: My parents were artists, so I was exposed to it at an early age. Music and acting lessons were also important to me, but the visual arts spoke to me the most. I loved the physicality of the process, and I could hide in it because I didn’t have to be in front of people.

MH: In your studio practice you work with unusual materials: yarn, wool, upholstery cord (aka piping), and recycled fabric, along with traditional paint. How did these materials find their way into your work?

SM: Everything is gradual with me. After years of figurative work, I began to slowly reduce everything to abstract shapes that resembled the figure. I started adding strands of yarn to my work, and in a yarn store I discovered these big ropes that turned out to be upholstery cord. It came in different thicknesses and was much more stable than the yarn, which kept fraying after I applied it to the canvas. Then when Covid happened we were living upstate, and I started knitting. I felt like the knitting was holding things together, like I was containing things, and I added it to a few of my pieces. I liked how it looked and got great responses, so I went forward with it. The knitting has become a meaningful part of my work.

MH: It’s often assumed that craft-based materials belong to the realm of the feminine, and therefore the artist’s work must be feminist. Is this stereotype annoying? And is your work overtly feminist?

SM: No, I don’t see it as feminist.

MH: It’s so refreshing to hear you say that! I find it mildly irritating when people assume that if you’re a female artist, you must be doing feminist work.

SM: I know that my materials are indicative of women, and early on I used feminism and repurposed materials as reference points when I talked about my paintings. But I don’t think of my work as feminist. It’s just me.

MH: It’s interesting that knitting is a skill that was passed down the generations through women. Maybe women of our generation don’t knit as much, and possibly our mothers didn’t knit, but I don’t think anyone has a grandmother who didn’t knit, right? Who taught you to knit?

SM: My grandmother taught me how to knit when I was five, so the act of knitting has always brought me great comfort. Throughout the years I would knit when I was under stress, and it has been both meditative and calming.

MH: So you gradually started losing the figure because you sensed that there was something underneath it that was much more important. What have you found in your exploration?

SM: What I’m exploring has to do with what’s inside, with one’s spirit and biological makeup. It goes beyond what overtly represents us in our body, face, and skin. It’s a form, it has circulation and a heartbeat and palpitations and blood, but it’s much deeper than that. It has to do with my feelings and how they connect to the outer world. All the various shapes in my paintings are attached to each other; they’re one form, and they’re an expression of what’s going on internally.

MH: It sounds like you’re expressing what it feels like to inhabit a body, rather than what it looks like. Not an easy task!

SM: Yes! When I’m knitting, I start working with the beat of my heart and I can go into an almost meditative state. It’s like I’m building tissue, repairing organs, connecting valves or shapes that are all working as one big form. The knitting connects everything and makes it whole.

MH: Your intuition that there is something underneath the figure makes me think of Plato’s concept of universal Forms. He stated that the individual forms that we encounter in this world are shadows of an eternal, perfect Form that exists in another realm. By departing from a literal representation of the figure, are you searching for something timeless and unchanging?

SM: Yes, I suppose I am, in the sense that the inner working of the human body is timeless and indistinguishable. At some point I could no longer represent the figure in a literal way; it had become too painful. It became more and more abstract until finally I took the leap into total abstraction. Once I did this, I found my way, but it was a painful transition for me.

MH: Why was it so painful?

SM: I no longer physically and emotionally identified with the human figure, and I knew I was moving into something else, but I wasn’t sure what that was. After I had made the transition to abstraction, I realized that it wasn’t full abstraction, but forms based on the inner workings of the body. I had moved from the external to the internal, and I was experiencing a deeper connection to what is felt rather than seen. This transition took a couple of years.

MH: Figurative work can be specific, as in portraiture, or loose, expressing the human condition in general terms. As your process becomes less literal, do you find that it grows more profound in some way?

SM: Yes, definitely. It goes back to Plato and essential, basic form. I feel we are just an extension of that form, and it can also be found in nature, in high math, and in philosophy. But it’s not only the form, it’s also about how it all fits together. I’m deeply connected to my work – it’s the inner workings of my mind, and that’s what I try to tap into.

MH: It sounds like you’re tapping into something raw and unadorned, without regard for outer appearance. Your work probably wouldn’t be a great candidate for home décor.

SM: I try to steer clear of decoration. There have been times when I’ve tried to make my work more attractive, but I found that it’s not something I’m into. If I use brightly colored yarn, it has to do with something inside me rather than a surface choice. But I don’t think of my work as pretty; in fact, a lot of my work isn’t all that attractive. I don’t know if anyone’s going to hang it in their bedroom!

MH: Maybe Plato. What about your choice of materials? How does the industrial piping cord fit into the picture?

SM: I communicate well with these materials. I feel that I’ve mastered them. For years I made sculptures and they were huge, but I had to stop because I couldn’t go any further with them. I didn’t know enough about the materials, and they became too heavy to move around. But these materials are manageable and they’re a direct link to my brain, my creative soul, my energy. I draw with the cord, fill it in, and connect the shapes with the knitting.

MH: You talk about your process in instinctual terms, and I get that your process is very intuitive, gut-based, spontaneous. In the absence of objective criteria, how do you know when a piece is finished?

SM: When I like it! When I feel that it does what it’s supposed to do. When there’s something in the piece that resonates with what’s going on with me.

MH: This is a quote from you: “The best work is a revelation of something that’s deep inside you, what makes you you.” Would you elaborate on that?

SM: All of a sudden you feel deep inside that the piece is yours. It happens when you’re working and not self-conscious; you’re just having a great time and then suddenly you feel at one with your piece. It’s why I keep doing it. It makes me live! You look at your piece and know that it’s touching something within.

MH: Does the painting become a reflection of you in some way, like a self-portrait?

SM: Yes! I feel like they’re my friends. I come into my studio, and I feel like I’m surrounded by my friends, and they’re all me.

MH: When one’s work is deeply subjective and intuitive, it’s not easy to talk coherently about its meaning. Do you consider this an impediment to a deeper understanding of your work? How important is relatability?

SM: It’s an impediment to explain my work to other people, and there are many artists who won’t talk about their work. I can understand that. I can talk about the material and physicality, but the deeper it goes, the harder it is to talk about. It’s important to me that people understand the work, but I know that a lot of people won’t really get it.

MH: Learning more about an artist’s work usually doesn’t make the viewer like it less. I’m wondering if it behooves the artist to open up and talk about their work even a little, just to give the viewer some context and a way in.

SM: I think so. I know that when I talk about my work and relate it to the figure and what lies beneath, it gives the viewer something to hang onto and allows them to go deeper.

MH: Does this circle back and add something meaningful to your studio practice?

SM: Yes, but it’s a thin line between connecting with yourself and crossing over that line with an audience. But it’s meaningful to get the work out there and feel like you’re part of the bigger conversation.

MH: What do we contribute as artists? If we’re not cranking out home décor or curing cancer, what do we add that’s meaningful?

SM: We make the world a richer place. Where would the world be without art? It would be terribly boring. Why even be here?

MH: You left teaching a few years back, and get to spend a good amount of time in your studio. Everyone has good studio days and bad studio days, so I’m curious what you consider a good studio day.

SM: When I come in and I’m able to connect with my work. I have to work through days of not connecting, and that’s very frustrating, but once I get past a certain point, I’m on the road and I know it’s going to work. There’s hope and there’s a full connection.

MH: Haha! There’s reason to live.

SM: Yes! But there are plenty of days when the forms are just not working for me so I have to yank up the upholstery cord and sand the glue down, then start over.

MH: What’s the best part about being an artist?

SM: You can do whatever you want. It’s wonderful to have these ideas in your head, and then be able to put it down on paper or canvas or whatever your medium is. Self-expression! We’re lucky because we have a way to express ourselves. It gives our lives meaning.

www.susanmastrangelo.com

CURRENT SHOWS

SLIP/SLIDE

with Larry Greenberg

490 Atlantic

through Nov. 3

490 Atlantic Ave., Brooklyn, NY

This Is Not A Rope

solo show

Field Projects

through Oct. 19

526 W 26th St., #807, NY, NY

Check out Susan Mastrangelo’s Wikipedia page here.