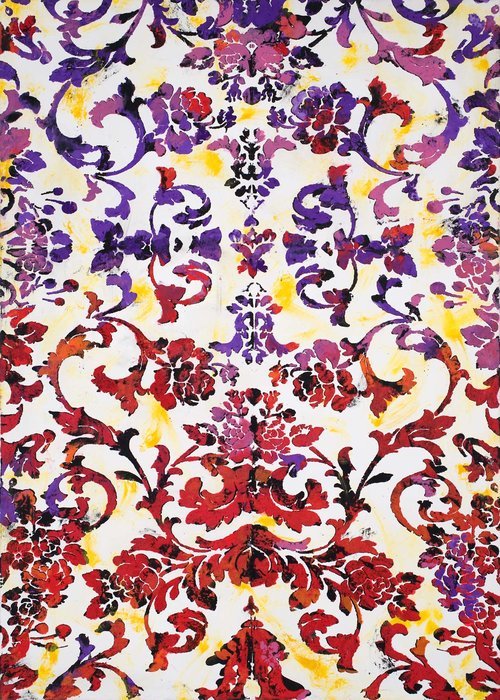

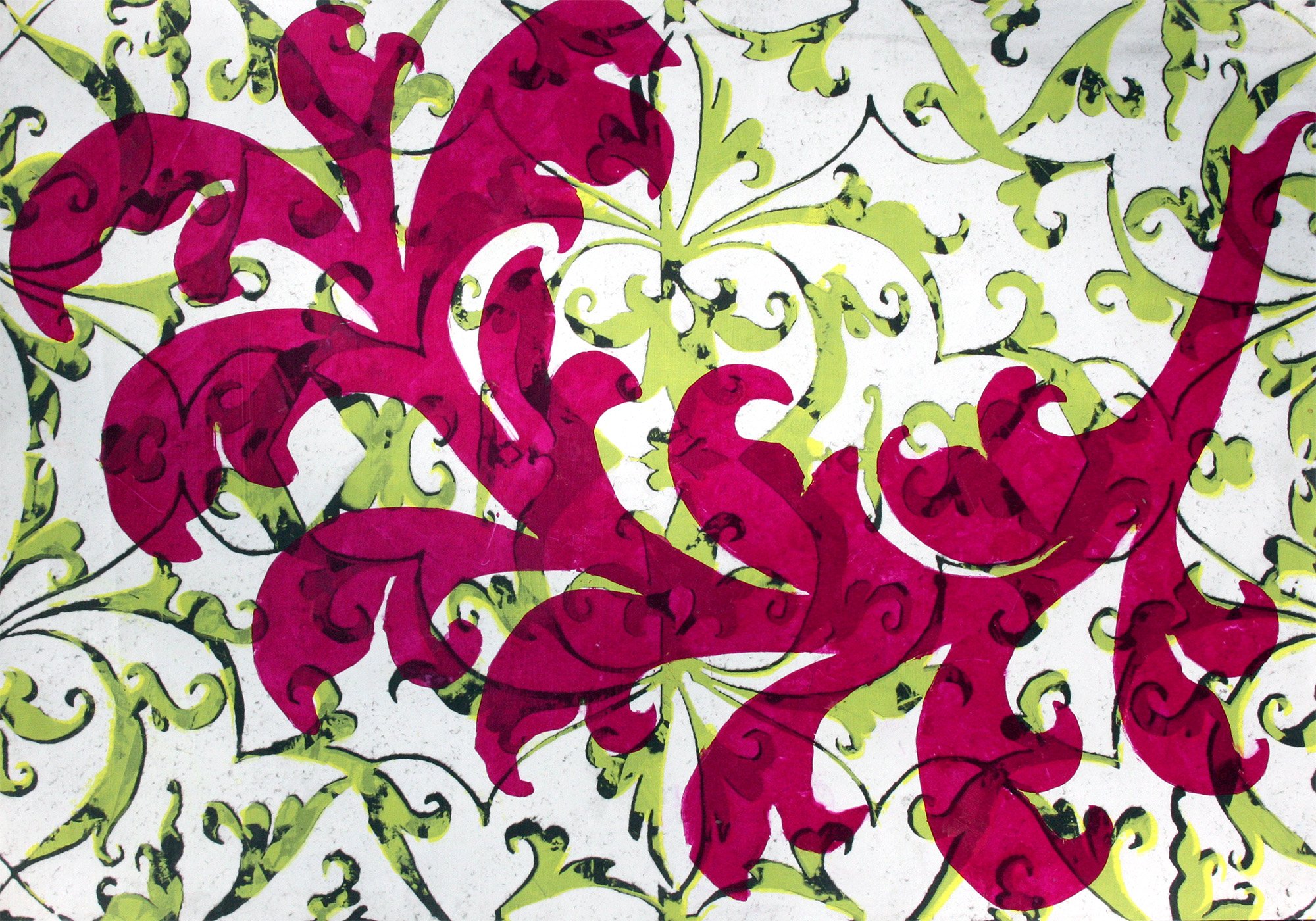

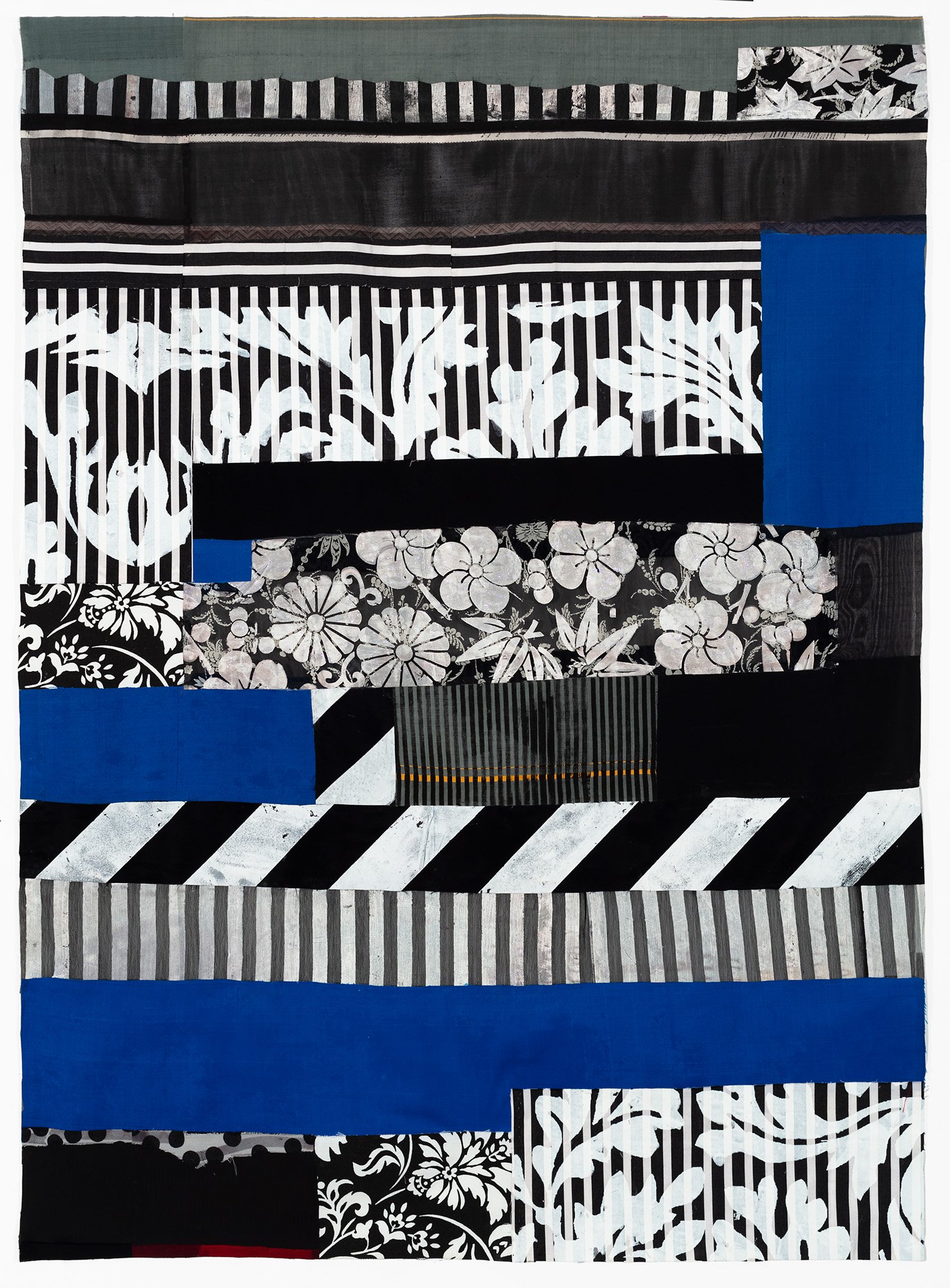

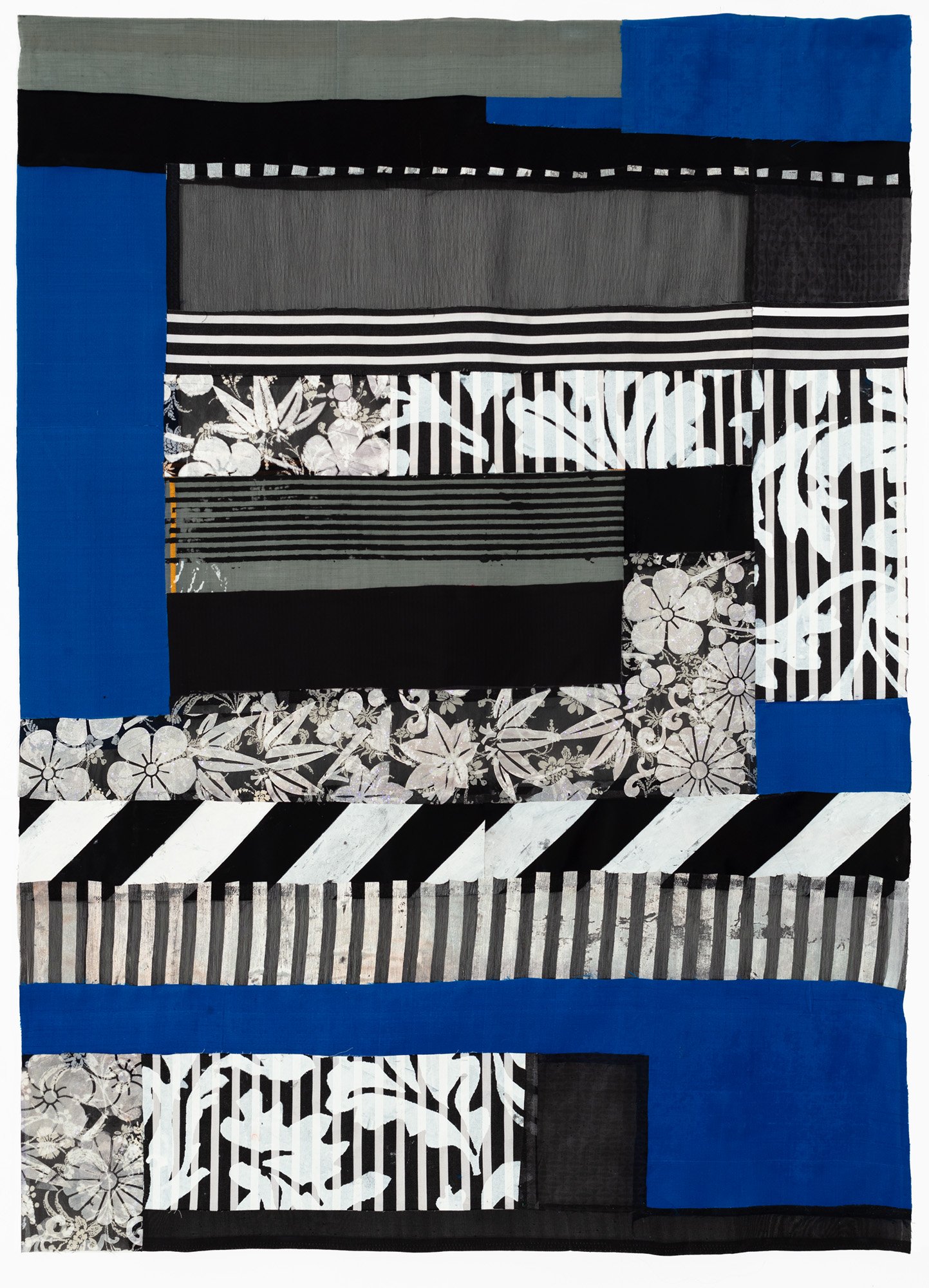

Margaret Lanzetta’s work is inspired by the patterns and textiles that emerge from diverse cultures, from the ancient past to the multicultural present. The graphic symbols and motifs that dominate her work have circled the globe for millennia, clashing and converging in their tribal, religious, or political affiliations. Through a process that involves screen printing, layering, cutting, and sewing materials, Lanzetta recontextualizes patterns to explore their long history of associations. She has spent extensive time in foreign countries, including Japan, India, Syria, and Morocco, where she immerses herself in the rhythm and heartbeat of the culture. Lanzetta’s sources include Buddhist iconography, Hindu nature-based patterns, Islamic geometry, and countless motifs that represent forgotten dynasties or conquered lands. Familiar symbols appear in the silkscreened layers, and a narrative emerges that speaks to such timeless issues as migration, land acquisition, and political alignment. What appear to be decorations are in fact declarations of privilege, victory, or the aspiration for greater power and wealth. But there’s also a thread of humanity that runs through Lanzetta’s work, the voice of the nations, tribes, and individuals who created the distinctive patterns – someone had to come up with the design, after all. The rich visual vocabulary speaks to the universal need for ownership and identity; indeed, humans like to own things and imprint their personal stamp on them. Lanzetta stamps and screen prints onto existing patterns, adding her mark to the countless narratives embedded in the fabric. Through her repetitive and meditative process, Lanzetta creates a multicultural tapestry composed of organic and geometric forms, like opposing cultures that come together and, in their synthesis, produce a more powerful alliance.

MH: You’ve been working with patterns and layering for a long time. When did you first become interested in this, and what were your early influences?

ML: I’ve always been interested in patterns and textiles. My grandmother sewed, and I started making my own clothes in sixth or seventh grade. I drew and painted from when I was a kid, then I took art classes through grammar school and my parents sent me to oil painting classes. In college I started making collages out of patterns cut from magazines, then I made paintings based on them. So patterns and layering manifested themselves early on in my work.

MH: It sounds like when you found patterning, you knew that was the direction you wanted to go.

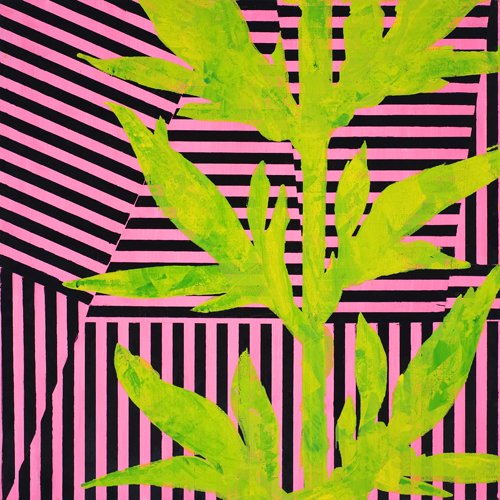

ML: Yes, it was always something that I really responded to. Even before I thought about what patterns were or what they meant, I was interested in their repetition. I was also influenced from a young age by my love of nature. I’ve gardened since childhood, and I have a garden outside my studio in Long Island City. My current work skews a bit more geometric, but organic and floral shapes have transformed into patterns that have been an enduring source of inspiration. I often photograph plants in my own garden, digitally transforming them into silhouettes for use in my work.

MH: Talk a little about your creative process. You use silk screen, right? How did that become your medium?

ML: Yes, silk screen is my primary medium. I silkscreen onto patterned fabric or Japanese paper, and I prepare the materials by cutting and layering, then reassembling them. I like the physicality of it, and it fulfills my need to work more sculpturally. I painted in college, but I never felt like a painter’s painter. I don’t think about the things that many painters think about, like space or light or illusion. When I came to New York I went to Parsons and gravitated to sculpture, which I did for about ten years, layering and stacking, cutting up and reassembling wood and industrial materials. When I started to work two-dimensionally again, it always included processes like printing and stamping. It’s the same as what I was doing with sculpture: cutting materials into strips and putting them back together in the way of repair or mending. The image comes about by accretion, layering and building the elements, and the repetitive process is a form of meditation for me, like a physical mantra.

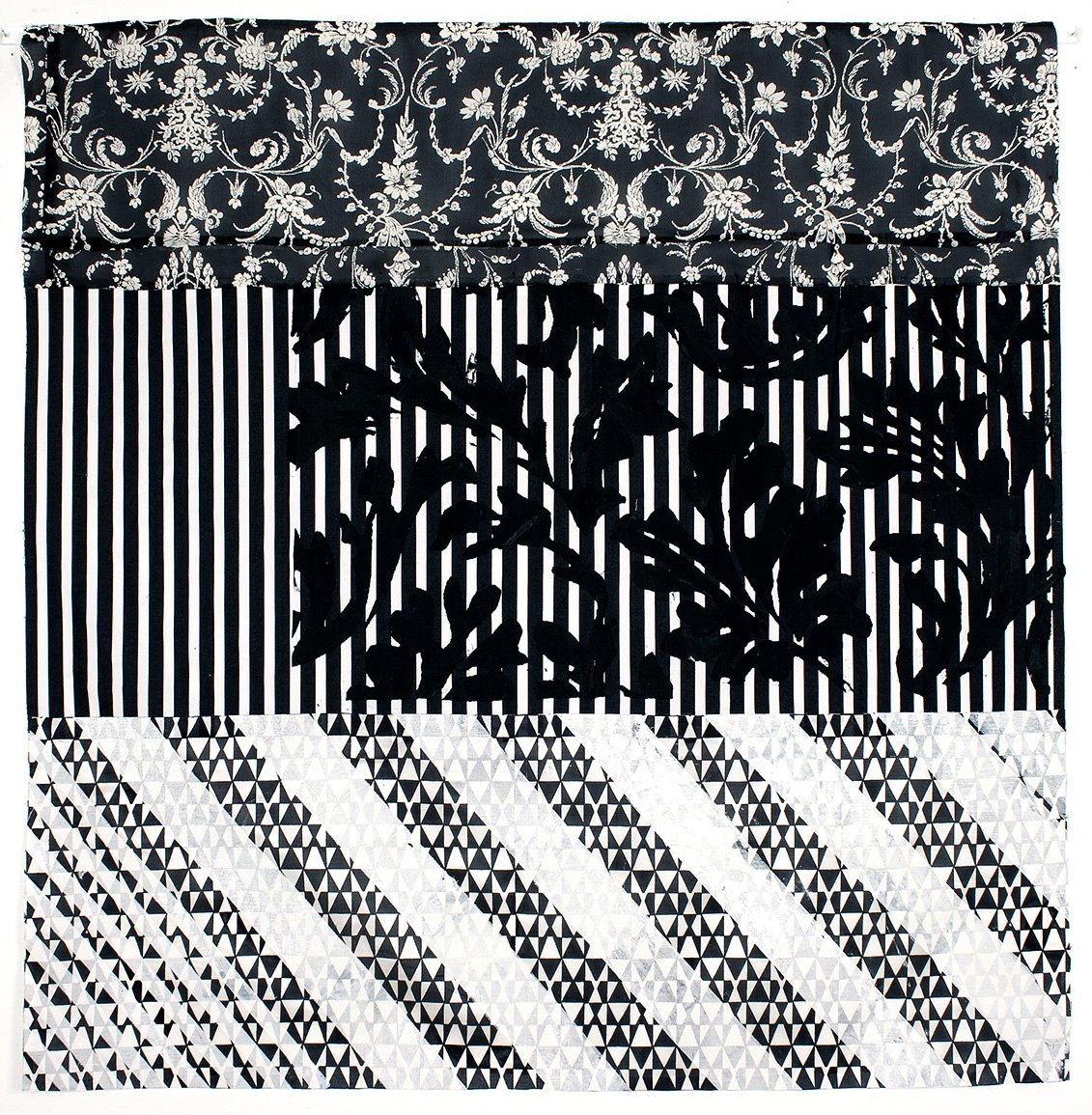

MH: Your most recent work seems to be more monochromatic than in the past. What’s behind that choice?

ML: My shift toward a more monochromatic palette is related to the revisiting of my large-scale, two-dimensional works from the late 90s. The silvers, blacks, and metallics dominated my work then, and referenced industrial materials. I’m interested in reinvestigating this palette and approach in my current work.

MH: Your work has a lot to do with cultures coming together and influencing each other either positively or negatively. How does this cross-pollination come through in your work?

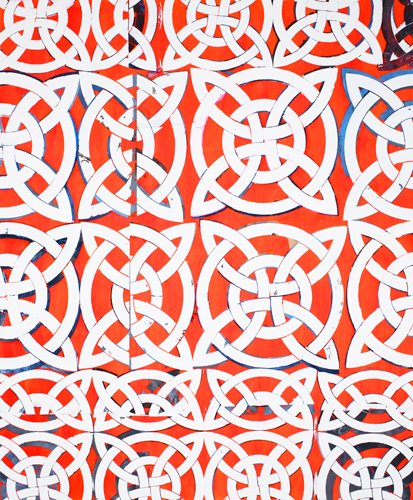

ML: It comes through in the textiles that come from all over the world, and I’m not hierarchical about that. I’ll often use textiles that I buy in New York, some of which are cheap. I don’t subscribe to using pure cotton or silk because that isn’t the reality of what’s being manufactured today or commonly used. A lot of sari fabric in India is rayon or mixed fibers because synthetic fibers are cheaper. Unfortunately, this contributes to environmental degradation because they’re not using natural dyes anymore. But all those drawbacks aside, the textiles can be stunning. I’m interested in patterns because they have a long history, and I mix them from all over the place. For example, the interlocking knot from Ireland is a well-known pattern, and is also found in Asian cultures. And in the U.S., the western bandana pattern that’s so familiar originated in India. I love this idea that there’s a visual vocabulary that circles around the globe through time from the ancient to the present, mixing these recognizable patterns.

MH: You sometimes incorporate patterns that clash on a cultural level, or that undermine existing political systems. Can you give me an example of a piece that embodies conflict?

ML: Gueliz is a piece I started when we were in Marrakesh. (see below) I wouldn’t say that it embodies conflict but expresses a rich confluence of patterns. The silvery fabric is from Burma, but the pattern is rectilinear, with a floral piece in the middle that’s straight out of the Mughal period. This was the period when the Muslims invaded India and brought their bold geometric patterning. The Hindu patterns were much more rooted in nature, so it evolved into a marriage between Islamic geometry and the nature-based patterning from Hinduism. The Taj Mahal is the crown of the Mughal period, and this pattern is also found on the façade of the royal palace in Fez, Morocco. So the Hindu/Muslim patterns found their way to North Africa and were translated into Moroccan handicraft tiles. Gueliz is the name of the neighborhood where we were living at the time, and it embodies all these different currents.

Gueliz, 2021-22, acrylic on Burmese brocade and Japanese papers on panel, 24 x 24 in.

MH: It seems that there’s conflict encoded in the design, even though the conflict is from the distant past. I find it fascinating that these gorgeous patterns that are now part of the Mughal and Moroccan heritage are rooted in conquest and pillage. You must go down a lot of rabbit holes when you’re doing this research!

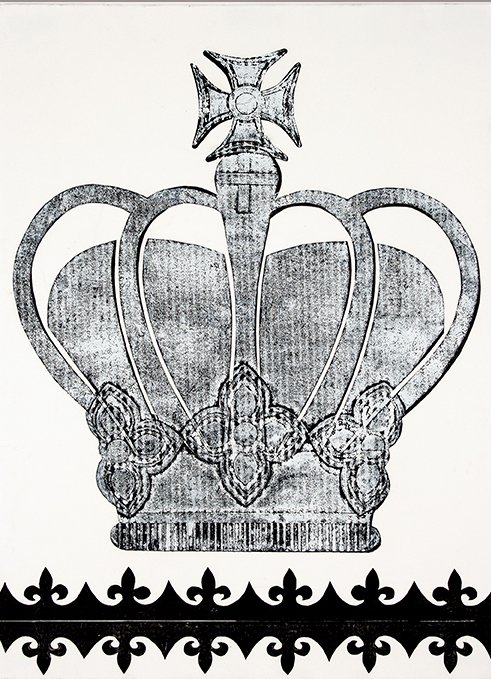

ML: I do. One series that I did was based on the symbolism found on crowns. I was at a residency at Greenwich House Pottery, and I decided to make crowns because I had been collecting crown imagery for a long time. So I went to the New York Public Library and started researching crowns from 1300 up to 1969, and I found that the symbols that are put on a crown can be placed into two categories. The first are symbols from a country that they’ve conquered, and the second are symbols from a country they want to form an alliance with. So there’s this massive dichotomy between symbols of power and symbols of alliance.

MH: Your patterns often reflect the geopolitical past and present. Would it be possible to layer them in such a way that the design could infiltrate an existing conflict and create a new dialogue? Say you came up with a design that layered Palestinian and Israeli motifs. Is it naïve to think that the patterns could influence an outcome in the war, or are they better suited to reporting what’s already happened?

ML: Doing a piece that married Israeli and Palestinian patterns? I wouldn’t touch that one right now. I don’t believe that art can solve complicated problems like that. I’m interested in the current of how people are using new patterns and sources and readapting them, but doing anything further in terms of infiltrating or changing things politically, that’s not something that I’d feel hopeful about.

MH: It’s interesting that something as innocuous as patterns printed on fabric can instigate life threatening conflict. I think of the Confederate flag, which symbolizes brutal racism to some, privilege and ownership to others, and wistful nostalgia to others still. How do we determine whose interpretation is correct when we’re making political decisions?

ML: In terms of the meaning, that’s in the eye of the beholder. To a Confederate soldier they’re prized flags, but to others, they symbolize horrific injustice. There are a lot of symbols that have opposing interpretations. Another that comes to mind is the swastika, which is reviled by most people, but there are some who find it meaningful.

MH: Your work isn’t only about conflict, it’s also the celebration of cultural heritage and the intersection of histories. Can you talk about that?

ML: Yes, I’m interested in how patterns migrate. What that usually brings to mind is the Silk Road or the early colonial trade from Europe to Southeast Asia, but it’s still going on. It happens in a different way now because pattern migration mirrors economic worker migration. People are constantly moving textile production factories, looking for cheaper places to manufacture. So people are migrating across borders in search of work, and it’s sad because economic migration often leads to worker exploitation, and the people are often working under rough conditions. And in a lot of these countries the environmental standards for production are very bad, so these countries that are producing magnificent fabrics are also polluting like hell.

MH: Beyond the concepts and experimental nature of your practice, are you searching for something more elusive in your creative work?

ML: When I’m making work it’s physically soothing, and the repetitive action and motion of cutting becomes a sort of meditation. I notice that when I’m not working and I get to the studio, I take a deep breath, like I’m glad to be there. But I don’t go to my studio to have “fun”. It’s definitely work!

MH: Does your studio practice ever feel like a carrot/stick situation? Like what you’re searching for is always just out of reach?

ML: Sometimes. I see a piece in my mind, but I can’t seem to realize it because the work veers off in its own direction, with its own mind. But this is how artists make art!

MH: There are a couple of terms that pop up when talking about artists. One is referring to someone as an “important artist”; the other is labeling someone as a “serious artist”. What do you think is meant by these distinctions? Do you find them elitist?

ML: Taken at face value, an important artist may be someone who’s making some commentary or talking about critical issues, like difficult social or environmental concerns. Or it may be an artist who makes a major shift in their work, an important change that influences how people look at art, like Pollock, for example. In other words, someone whose work breaks with the paradigm and moves to a different level. And a serious artist is someone who’s committed to making thoughtful work. I’m not sure if they’re necessarily elitist terms.

MH: Do you think the work you do is important? And do you think of yourself as a serious artist?

ML: I consider myself a serious artist. I’ve dedicated my life to doing this and I’ve eschewed doing a lot of other things with my life. An important artist? To me it’s important, but I try to have a little perspective on that as well. I see a lot of work that’s amazing and maybe better than mine, so I try to keep my sense of importance in perspective with a bigger world, and a bigger arena of artists making work. There’s a lot of really good art being made, and there are a lot of artists making interesting work who aren’t household names, but that doesn’t mean their work isn’t great.

MH: Do you think your work is conveying something important?

ML: Yes, I think it’s conveying issues that are important to think about. We ought to be aware of how all these global cultures are swirling around and are not isolated, and how that shows up visually in our everyday lives.

MH: Does being a serious artist has a compulsive quality that involves a degree of obsession? Sometimes it can even show up as an addiction.

ML: Yes, I think being obsessive about working is common to a lot of artists. There’s a strong pull to be in the studio and to make work. Creative people are different than those who have an office job, and artists can be obsessive, for good or bad. I just accept this aspect of myself, even though I don’t quite understand it.

MH: What’s the most important thing that people take away from your work?

ML: I’m not hierarchical in what I want people to take away. I prefer that my work has different entry points so that viewers can enter it on different levels and take from it what’s important to them. I like it much better when people bring something of themselves to the work, and then take from it as they interact.

MH: We’re having this conversation via Zoom, while you’re at an artist residency in Bangkok. Tell me a little about that.

ML: My husband and I are artists and we rent a studio and living space where we can work and be away from our day-to-day responsibilities. I’ve been to Bangkok many times since 1982, so it’s a city that I’m familiar with. I love New York but I find that my responsibilities there and the social connections draw on my time, and I feel like I’m never catching up. So when I go away I have these blocks of time to make work without distraction, plus it’s warm! And I’m comfortable working on the road, so I can easily pack up my studio, and as long as I have a flat surface, I can work.

MH: What’s the best part about being an artist?

ML: I wanted to be an artist from the time I was five. I wanted to have an airplane and fly around the world, so I guess I’m doing that! I like looking at work and seeing what other people are doing, so if I wasn’t an artist, I probably wouldn’t be doing that as much. It opens my mind to see how other people think and the ideas they come up with.

www.margaretlanzetta.com

\\\

UPCOMING SHOWS

Anywhere But Here, Project: ARTSpace, NY, NY, May 8 - July 7, 2024

Travelers, Liars, Thieves, Garrison Art Center, Garrison, NY, May 25 - June 23, 2024

\\\