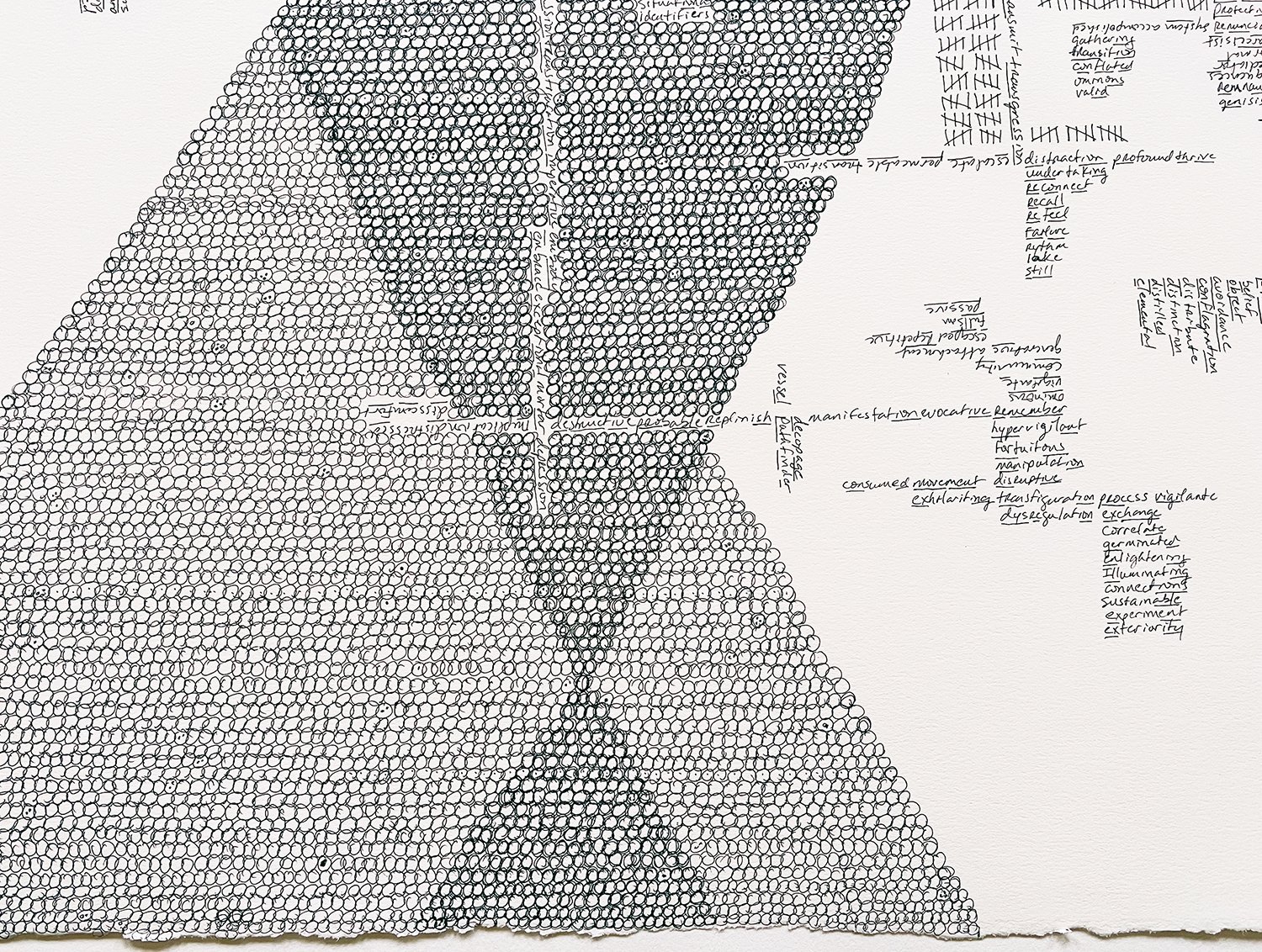

Susan Luss is a multidisciplinary artist who excavates her personal history to create complex psychological environments. She incorporates draped canvas, dye, and found objects, arranging and rearranging them in compositions that point to desire, connection, and transcendence. Like the subterranean networks that connect trees and fungi, Luss establishes spatial relationships between found objects, some visible and some felt. As we wander through her installations, we create our own connections between the disparate elements, leaving traces of ourselves in the process. The space is further animated by natural light that filters through colored gels placed in the windows. As with stained glass, the suffused light transforms the architecture into a sacred space, enhancing the desire to connect and comprehend. This is a transitional space, one in which we’re inclined to pause but not linger. As Luss places the found objects in meticulous arrangements, she creates meridians with which we may align, immerse, and integrate. A tall order to be sure, but Luss’s work is powerful and empowering, offering the prospect of personal transformation. Its larger-than-life scale sets the stage for dramatic psychological shifts if the participant is so disposed, and if not, there’s plenty to gaze upon. The urban detritus placed about the floor – rusted machine parts, bricks, ragged cardboard – are outward manifestations of Luss’s internal process, in which she recalls aspects of herself through collecting and engaging with the various objects. Her dye-stained canvases are draped, not hung, evoking the veils and shrouds of classical painting. Luss often brings these oversized canvases outdoors, where they interact with the landscape and the subtle movements of her body. As she lifts the heavy fabric at its edge, it catches the wind and finds equilibrium for a moment before succumbing to gravity and settling back to the earth. Perhaps this is an apt metaphor for Luss’s inspirational work: a fleeting moment of transcendence, followed by a gentle return to the earth.

MH: Your work is difficult to place in any of the usual categories of artmaking. Painting, performance, and installation come to mind, but those labels limit its breadth. How do you think about your work?

SL: My work is a compilation of my life experience, a way of connecting the scale of my body to the scale of the environment. It’s about process and movement and transformation over time, and the work reflects forward movement and expansion. It deals with a longstanding desire to be deeply rooted and attached to something outside of myself, but absolutely free. My work is also about the relationship of the parts to the whole.

MH: The different mediums, you mean?

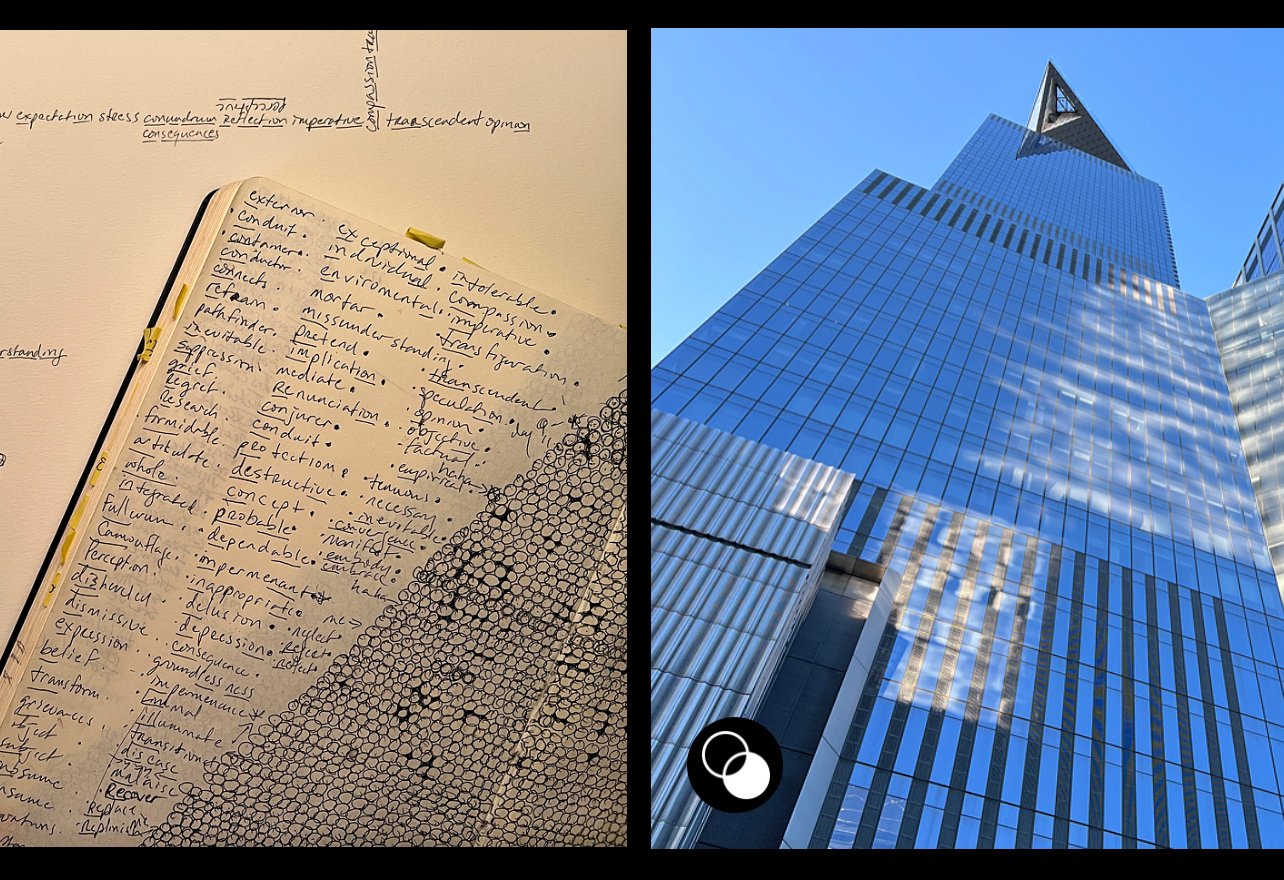

SL: Yes, the different mediums act as tools that provide me with material for my work. I take a lot of walks in the city, during which I collect objects that I use in my assemblages. The thought process of putting these little parts and pieces together into a new kind of relationship is an important aspect of my work. So the different mediums are the parts of the whole, which is the whole self.

MH: You don’t seem like the kind of artist who’d be happy just painting or sculpting or doing one thing. It seems like you need to do different things to be fully engaged in your practice.

SL: Yes. I don’t think I could be limited to one art medium, it’s more environmental. I’ve painted before, and I painted the environment of my experience within the borders of the canvas, but everything outside of the canvas also become part of it. And this is what I’ve learned over time, how my work is expressed through these different mediums.

MH: When one enters your studio, it’s like entering an installation. As I wandered through and got my bearings, it slowly emerged that I was an integral part of it, and without my presence, it wasn’t complete. Do you feel that as well, that your presence is essential to consummate the piece?

SL: I do feel that I’m an integral part of my work because it’s coming through me. I’m part of the whole experience, and when I leave the studio and come back, I’m more aware of my connection to it. When I’m inside it, I’m less aware of that. I’ve become keenly aware that when people visit my installations, either in my studio or out in the world, they became a part of the piece. Their history is embedded in it, and even when the installation comes down, those peoples’ experiences are still there.

MH: For me it had the feeling of having unwittingly wandered onto a stage, and in the next moment I realized that I was the lead actor in this performance. Except that I didn’t feel that I needed to perform; I simply needed to be present.

SL: It’s interesting, each person who comes into my studio or who sees a performance comes in with their own life experience. Someone once said to me that when she came into my studio, she sensed everything there was resting and waiting to be activated. It’s not uncommon that visitors feel they’re part of it, but it doesn’t require anything of them.

MH: I would guess that everyone who comes into your studio animates the space in a different way.

SL: Yes, and it can only be that way because their life is unique, and they can only animate it from their own life experience. That also happens when I’m with the work outside and someone spends some time watching what I’m doing. The canvas is an extension of my body, so every time I do a performance in Central Park or in the city, the wind blows through it, and the ground becomes a part of it, and the people walking by or watching become an active part of it.

MH: When someone walks into your studio, they basically enter your painting, your world. And it takes a minute to realize that they’re not just looking at a painting, they’re in it. Is it important to you that the visitor becomes present enough to realize this?

SL: When I’m making my work, it’s the most present I am in the world. But I don’t set things up so that the viewer needs to be present, it just happens. It’s like when I leave my house and go out into the world, I’m either present or I’m not. But I don’t have to go to my studio to do that. I can do it in the world every day.

MH: Your work seems to be highly orchestrated, with the various elements arranged in a tight composition. There’s the sense that they’re in dialogue with each other, and I’m curious if you know what their conversation is. Are they talking about you? With you?

SL: They’re talking with me, less about me. I make a mark, and the mark talks to me about the next mark, and I get into this relationship with the lines. It becomes a dialogue where the language isn’t definable, but it’s visual and physical. I found out by accident that all the floors in my studio have a bit of a tilt, so there’s some gravity at play in my work. I use what’s available like the slope of the floor and respond to it by orchestrating the composition with that in mind.

MH: When you’re done working and leave the studio, do you think the elements continue talking to each other?

SL: Yes! I say goodbye to my studio every time I leave, and I set it up to be ready for my return. I imagine things happening and energy flowing when I’m not there. I’ve been thinking about setting up a time lapse camera so I can see what happens when I’m not there. (haha) I know it’s kind of woo-woo!

MH: Yes, but it’s also an interesting concept. All artists have that experience where they hate what they’re working on and want to shoot themselves, then they go back to the studio the next day and the piece has come to life. So what happened? Has the painting rearranged itself during the night? Or in your case, when you leave the studio do all the objects strike up a conversation? Like, “Hey everybody, she’s gone! Let’s get to work!”

SL: Yes! I like that idea. There aren’t very many times that I leave my studio feeling disappointed, but when I do and I come back the next day, I feel grateful that it worked out.

MH: I’d like to hear you talk about the canvas. You paint on raw, unstretched canvas, which you describe as an extension of your body. I find this interesting because your canvases are so huge. Why are you compelled to work on such a large scale?

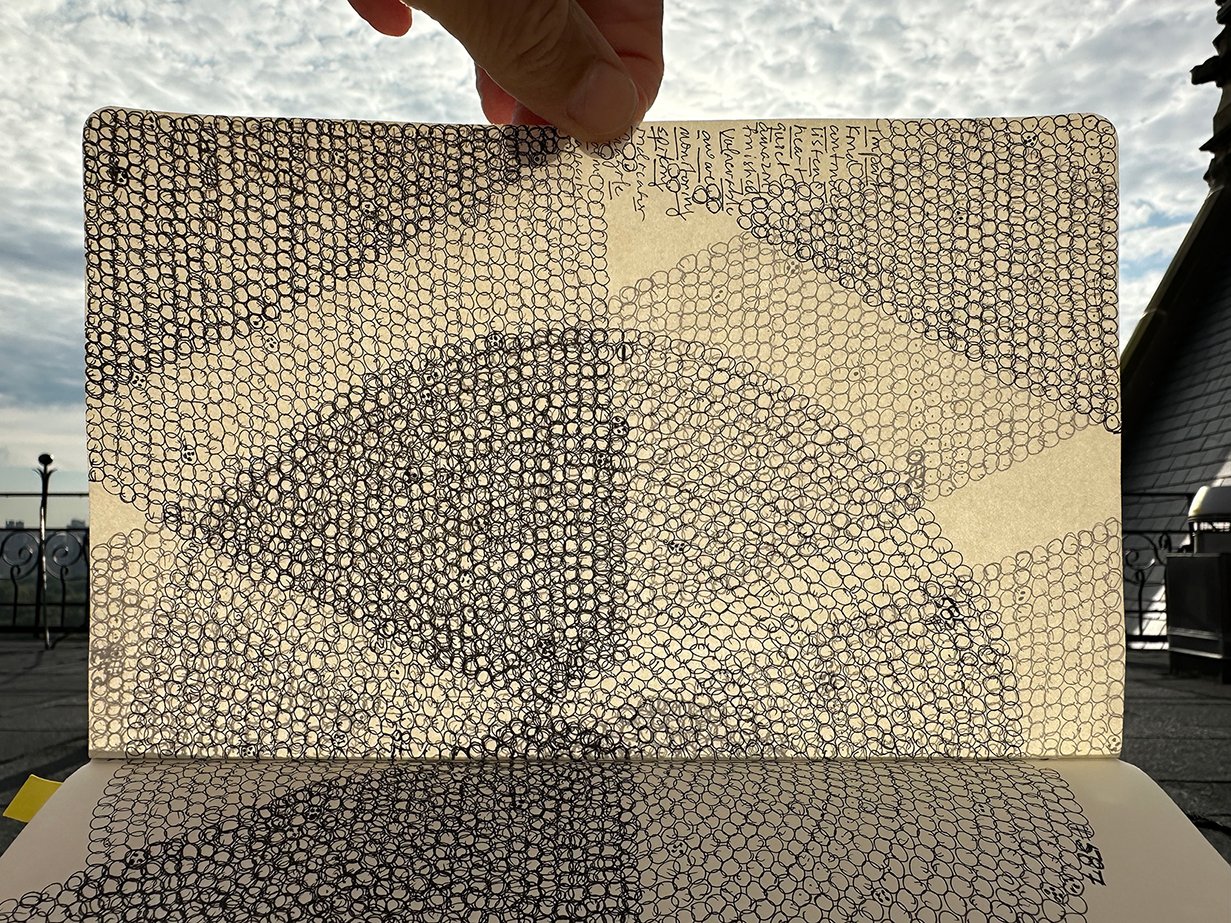

SL: I work on a very small scale as well, but I started working on unstretched canvas when I was at Pratt because it felt like freedom and expansion, since the edges were no longer confined. The canvases got bigger and bigger in relationship to my body, and the larger canvases got me physically engaged. It felt like a heavier container, a physical and emotional weight. So it has to do with expansion and weight and a mental space that can spread out.

MH: Your work is an interior process in that it’s an expression of an interior state. But then you take it outside and let the work interact with nature. Would you describe your experience of taking the canvases to Central Park? How did that change your relationship to the work?

SL: Before the pandemic I started taking canvases outside and grinding them into the dirt, then I’d dye them and drag them around Long Island City. Then the pandemic happened, and I had to get outside, as that was the place where I felt safe. I took one of the canvases to Central Park and walked around with it, and no one was around. I went to Sheep Meadow and started working with my body and the wind, bringing the canvas out in the elements, and letting the rain alter the canvas. The performative aspect was like a ritualized intervention, and I became aware that by caring for the canvases I was caring for myself. So the isolation of the pandemic opened me up and moved my work forward.

MH: That’s interesting. Do you think of the canvas as a second skin?

SL: No, that doesn’t resonate with me. But when I stain the canvas, I feel like I’m staining the body, so it’s a metaphor for the life experiences that get imprinted on us over time. That’s why I love the dye on raw canvas — it’s like breathing.

MH: I’m interested in how an artist knows when her piece is finished. What do you think? Does it have to do with the execution being complete? Or is it more about the successful communication of a thought or feeling? Or maybe it’s simply the urge to post it on Instagram.

SL: Usually what happens is some chatter in my body or brain, and I sense when something is getting to its apogee. I’m aware when a work is close to that, because the canvases contain the energy of whatever I’ve done with them and they’re ready for me to go on to the next work. Sometimes the works aren’t finished, and I can accept that, because sometimes things can be left incomplete.

MH: When an artist has been doing her work for a long time, it’s no longer about making a likeness, or even making a statement. It becomes something else – a search, or a longing – something ineffable, but we all seem to agree that the compulsion goes beyond the activity and technique. What is it that drives you in your creative path? Do you know what you’re searching for?

SL: I would say wholeness, the body/mind/spirit connection. As far as the compulsion, I know that I have to do what I’m doing, and create for myself first, because I’m searching for self-awareness and knowledge and clarity. And I don’t believe that’s necessarily going to be answered through the work, but through my life. I think I’m driven by the desire to be as aware as I can be of the reality of living.

MH: I know that you don’t regard your creative work as therapy, but is there a healing aspect to what you do? You’re translating your complex psychological makeup into an external visual form and in the process is there some sense of relief, as in releasing long held beliefs or burdens?

SL: Yes, there is a release. I don’t think about it ahead of time, and I didn’t start making my work for this reason, so I experience my work as I’m making it for what it is, a creative process. When I step back, I see the work more objectively, whereas while I’m in it, it’s more subjective. This has nothing to do with healing, it’s more like poetry. I’m translating my experience through a medium. But the part about healing is a troublesome concept for me. I don’t feel like I need healing; I feel like I’m okay just the way I am.

MH: As visual artists I think we make work in part so we can work on ourselves, because it’s difficult to work out our issues when they’re in the shadows. So we project our issues outside of ourselves, and we make stuff by painting, scraping, splashing, erasing, carving, whatever, and in the process of engaging with these tactile materials, we establish a sense of equilibrium. Does that resonate?

SL: It does resonate, but I do it differently. The things I collect are representational of something inside me, that’s a part of me, but I don’t have a language for it yet. So in collecting these objects, I’m collecting myself, and then using the materials to help me recognize the parts of myself that I had suppressed. I didn’t have access to my inner person, but through the visual creative process I’ve learned to recognize myself in the world.

MH: It’s an unconscious process, but in some ways that’s better, otherwise you’d get in the way. The whole thing feels like this huge, interactive process of healing or transformation that’s making you fundamentally whole.

SL: Yes, and when my life is over, all those things will be connected. I’ve felt for a long time that death is a culmination of a life that has been lived to the extent that it can be, and at that moment in time when I die, I’ll have learned everything I can in this life.

MH: I know you came to your practice later in life. Do you have any regrets around this, or does the timing feel right?

SL: I have no regrets. I have some sadness that because of my parents’ lack of nurturing and involvement, I had no way to recognize myself. But I accept that, and my potential is embodied in the work. I got a huge amount of life experience and satisfaction in working with people for most of my life. I’ve loved that kind of engagement, and it laid a different foundation for what my experience is now.

MH: We started this conversation last June, and I know your life has been very full in the last year. Has your work shifted in relationship to these recent experiences?

SL: One thing is that I’m working on a smaller scale, using canvas remnants, which is an aspect of my broader practice of reuse. It’s still a scale in relationship to the body, but more intimate. I’ve also been incorporating new textiles. One is border lace, which I came upon when cleaning out my mom’s house in January 2023. By attaching the lace to the canvas by hand, it acts as a real border delineating the landscape while adding new textural relationships. I remembered recently that sewing was important to me when I was growing up and I’m finding intriguing correlations from past to present along with pleasure in returning to this craft.

MH: What’s the best part about being an artist?

SL: The opportunity to recognize myself through my creative work, and then to recognize myself in others and others in me. The creative process feels to me like I’m home, like this is the person I’ve been all my life who was hiding in plain sight. I feel so much gratitude to be where I am now, even if it took 50 years of my life and all the drama. It just added to the well that has no bottom.