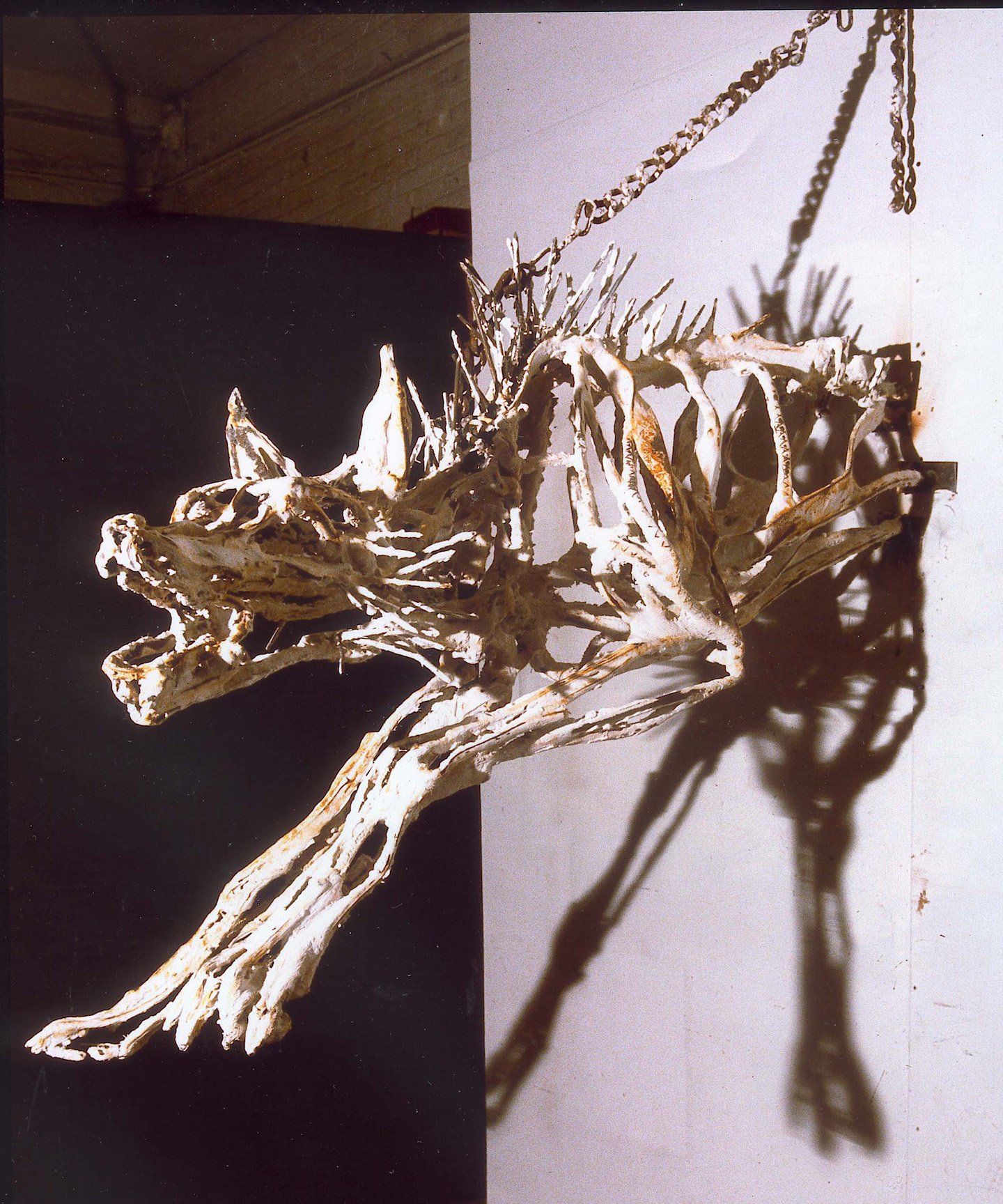

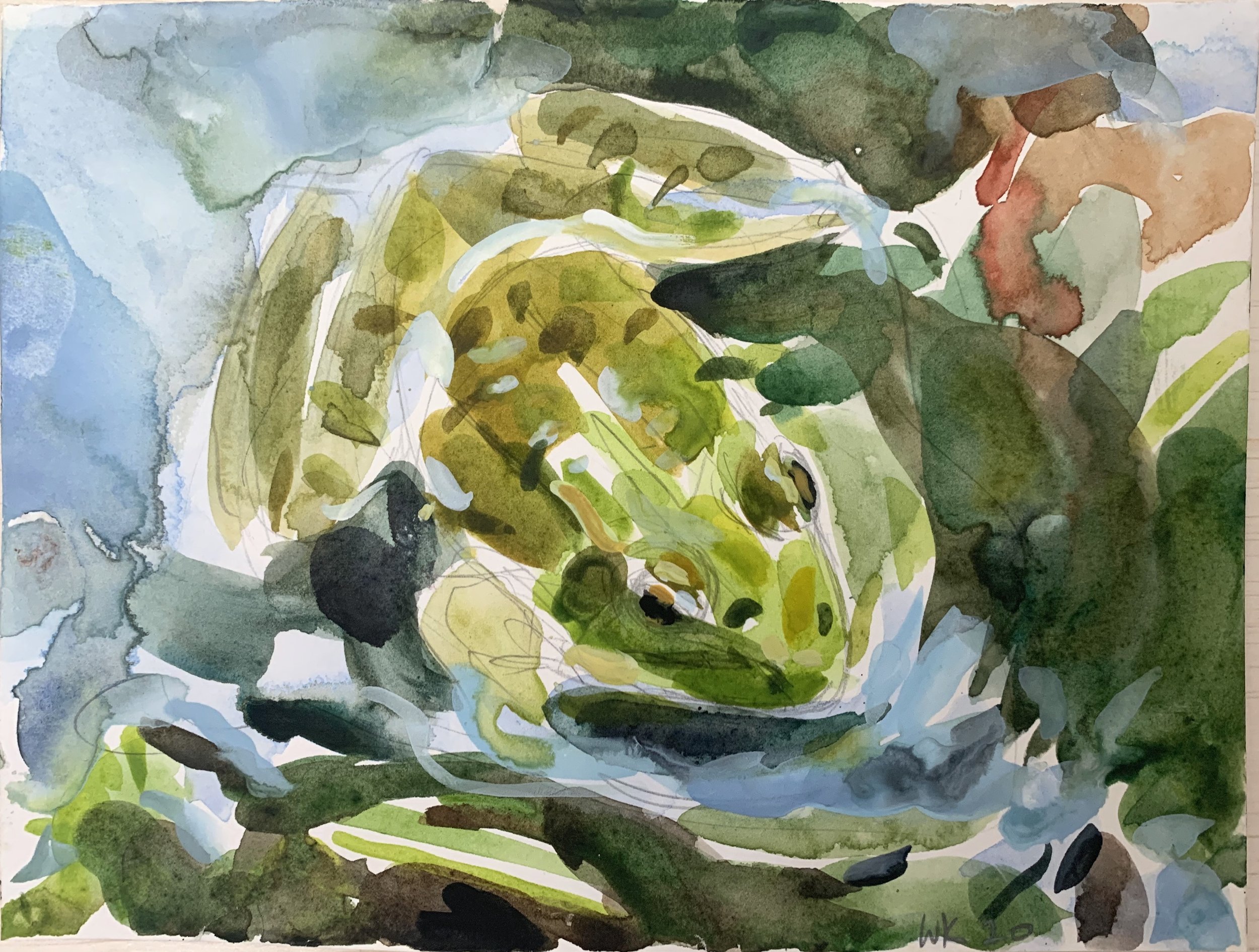

A few years ago, my husband and I were driving along the coast of Maine, when we came across an outdoor sculpture in a clearing. We pulled over to check it out, and what we thought was an abstract sculpture turned out to be a life-size elk made of welded rebar by Brooklyn sculptor Wendy Klemperer. The encounter was magical, not only because we knew the artist, but it was an experience, like a fortuitous sighting of a live elk. Had we come across the sculpture in a Chelsea gallery, the white walls would have diminished its impact, reducing it to an intriguing but relatively inanimate object. Klemperer’s animals come to life when encountered in their native habitats, where light and shadow play off the surfaces to create a haunting presence. Her work carries the majestic quality of an animal in the wild, embodying the dignity and freedom that humans yearn for in their gentrified lives. But her sculptures are also markers of absence, as the rebar defines the animal’s contours without filling them in. Klemperer says that welding rebar is like drawing in space, and indeed her process allows us to see through the spare lines of the form into the surrounding landscape, connecting the animal with its environment. Her watercolors similarly camouflage the creatures within their natural habitats, mimicking nature and capturing their essence with masterly brushstrokes. (Check them out—they’re absolutely stunning). A distinctive aspect of Klemperer’s work is its complete absence of anthropomorphism, a singular feat given the subject matter’s propensity for abject cuteness. There are no fuzzy foxes, dewy-eyed does, or whimsical porcupines to tickle our fancy. Instead, she portrays everything from grazing fawns to predatory beasts with a reverence that honors their authentic, untamed nature. Klemperer reveals the intrinsic qualities in each animal, embeds them into her sculptures, paintings, and drawings, and allows us the privilege of experiencing them through her unique vision.

MH: Your sculptures and drawings are inspired by your love of nature and animals. How and when did that show up in your life?

WK: As early as I can remember, I had an affinity for animals. I was always fascinated by them and wanted to be around them, and when I played, I pretended that I was a horse. Like a lot of girls, I was obsessively in love with horses, and I first got on one when I was 4 or 5.

MH: Did your parents encourage it?

WK: They didn’t discourage it. They couldn’t afford to buy me a horse, so I cut out pictures of them and plastered them all over my walls. We had a dog, cats, and I once gave my mom a mouse for her birthday. My pets through childhood included gerbils, parakeets, a baby alligator, an injured bluejay, and a rabbit that I got when I was around 10 and was still around when I went off to college. We spent summers in New Hampshire, where I spent a lot of time catching frogs and snakes. I had a pet garter snake that my parents allowed me to take home at the end of the summer, and it had 26 babies, so my parents were tolerant of all this stuff. When I got a little older my mother and sister and I would ride horses near where we lived, just outside of Boston.

MH: I see that you have a BA in biochemistry from Harvard, which could have led to a very different career. What led you to leave that behind and pursue an art career?

WK: My parents were scientists and chemists. My father taught chemistry at Harvard and my mom worked there for over a decade, and then did research throughout her life. Science was almost their religion, and they encouraged me and my siblings to pursue it as a career. But I didn’t have a great ability for it, other than my connection to the natural world. I was always drawing and painting in high school, and I was interested in literature and languages. But then when I went to college, I kind of fell in love with biology. I was fascinated by DNA and how it reproduces itself, and unlike philosophy or psychology which tends to go on and on without resolution, science gave me answers that made sense. But each semester I took an art class, mostly painting, and then in my junior year at Harvard I took a sculpture class. That’s when making art really started to click. So I completed the biochemistry degree, but I was falling in love with art by then, and right after Harvard I went to Pratt to study art.

MH: It’s magical and/or fortunate when an artist links one of her passions to her studio practice; it effectively links two paths into one. When did you connect your love of animals with your creativity?

WK: When I was a kid, everything I drew was an animal, so the connection was there from the start. When I moved to New York I was influenced by the gestalt of the time, and at Pratt I got swept up in neo-expressionism. I painted large landscapes with animals in them that kept getting more abstract, and I was making small clay and wax sculptures of horses. Later, at a residency at MacDowell, I started making animal sculptures out of tree branches, which was tedious because I was wiring them together. I hadn’t yet learned how to weld.

MH: I’ve been reading Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees by Lawrence Weschler. This is about the artist Robert Irwin, who died recently. Irwin had an intriguing quote: “The object of art may be to seek the elimination of the necessity of it.” What do you think about this statement?

WK: I think what he’s saying is that when you’re making art, you can get into a certain state where you’re very connected to what you’re making, and that is the art. You’re in a state of heightened awareness and perception, and that’s as important as the art object that comes out of it. That’s where I go with it.

MH: That’s interesting. So as artists evolve, they may value the process of creativity over the making of more objects. The art object would conceivably become obsolete?

WK: Right. You may be in your studio making stuff all the time, but those moments when you’re really connected and in the flow aren’t always there. It’s something that you’re always trying to get to, and there’s all this time spent trying to get into that state of engagement. I remember seeing Irwin’s work at the Getty in California, where they have his garden design. I had this moment where I couldn’t tell if I was looking at an object or a light, and it threw my perception off. It seemed to be more about the experience.

MH: My read on Irwin’s quote was that the objective of art may be to eliminate the artist’s need to create it. Would there ever come a time when you no longer needed to create art? Or is art making a necessity for you?

WK: I think I’ll always need to make art. It’s an uncomfortable necessity in a way because I’m always searching for something and trying to express it, and there’s no plateau; it’s always slipping away. It’s part of the nature of artists. I feel like I’ll always want to make things, and recently I’ve been getting excited about painting again.

MH: Many artists say their studio practice is a form of therapy. Is that true for you?

WK: I have mixed feelings about that. Sometimes people who don’t do art as a vocation think that art is so therapeutic and relaxing, and I find that to be a hobbyist attitude. I don’t find it relaxing; for me it’s physical work and can be exhausting. I can get into a flow when I’m warmed up and physically engaged, but it doesn’t just happen—it’s work to get to that point. There’s a lot of anxiety and disappointment and frustration in art making.

MH: Right, and in that way it’s like a spiritual practice, in that it’s not all peace and unicorns. But when I go into my studio and engage in my process, it’s a form of therapy in the sense that I’m pushing up against all my demons.

WK: In that context I’d say yes, a studio practice is a way of working through to something deeper. I find that when I’m working and connected there’s something magical that happens, when you feel like you’re not in charge anymore and something is pushing you along. Some artists think of it as a higher power, but for me it’s more about pushing away all the barriers, all the nay saying, and getting to a part of myself that is deep and true and free.

MH: In traditional psychotherapy, one of the objectives is to bring the analysand to a place where she no longer needs therapy or therapist. From that angle, Irwin may be correct that the artist could achieve enough psychological equilibrium that she no longer needed to create art.

WK: But maybe you can only get to that state of mind through making the art, so why would you not make it? Because the equilibrium is always a process; it’s not like it’s just there. You have to get to it. I have a practice and a process, and I’m not floundering the way I was in my late 20s. I have a confidence now that I didn’t have back then, but there’s still an element of searching and questioning because as an artist you always want more. You always want there to be development.

MH: I think it was Rilke who said he never went into analysis because he was afraid that he’d exorcise his demons and no longer need to write. Do you need your demons, or shadowy self, to create the work you do?

WK: When I was younger I needed my demons and all that struggle, and my sculptures were often aggressive or violent. But in the last 15 years or so that’s changed, and I’ve been trying to struggle less and get out of my own way, especially with my paintings, which are more elusive and fragile than the sculpture. I can allow the image to be serene or even gently appealing, which I used to avoid like the plague. Animal sculptures are always in danger of being interpreted as cute! I hate it when people use the word “whimsical” to describe my work.

MH: Another interesting Irwin quote vis-à-vis the art objective: “The experience is the thing, experiencing is the object.” What do you think about the idea that art is more about the experience?

WK: I agree with that. The artwork is something that excites thought and conversation, but it doesn’t inherently contain those things. I also find that as a viewer, art is very mood dependent. If I’m in a right state of mind it can be an amazing or ecstatic experience to look at art, but other times it’s just not there, because I’m not receptive to having that experience.

MH: A few summers ago, Kurt and I were driving north along the Maine coast, and we pulled into a campus or recreation area. In the distance we saw this intriguing outdoor sculpture, and as we got closer, we saw that it was a Klemperer. Coming across your work in an environment, as opposed to a gallery, feels like an important aspect of your work. it creates more of the experience that Irwin refers to.

WK: I think the piece was probably Calling Elk at College of the Atlantic in Bar Harbor. I had a sculpture exhibit on the campus, and they eventually purchased that piece. When I was first making work, I naturally wanted to put it in galleries, and I was showing in a gallery in Soho in the early 90s. But it was when I started showing in outdoor sculpture shows that something started to click on a lot of different levels. The landscape created a context and narrative for the work and allowed it to be seen in a particular way. And then being outdoors and physical is important to me. I’m very connected to nature and that’s where I feel free.

MH: It’s hard to imagine your work in a slick, white-walled gallery. The sculptures would almost feel like taxidermy, and maybe that’s what Irwin was getting at—that art as an object is lifeless, like a stuffed fox. It’s only when we have the experience that it comes alive for us. But then the next question is, what does it mean to experience art?

WK: My rebar sculptures can be difficult outdoors because they sometimes disappear if they’re against a shadow or tree. So even though they’re metal, they’re super ephemeral, and I feel like that’s important to the work. I think the experience that Irwin refers to may be the discovery. You may not see the sculpture at first, but then the light shifts and you see it. It’s going to be dependent on the site and the lighting and all that stuff. It’s not always the same, and it’s not the same as if it was sitting in a gallery or museum. I’d still love to show my work in a gallery, but it’s true that in that context, it wouldn’t have the reverberation that it does in nature.

MH: It really wouldn’t. When we saw your work in Maine, it wasn’t just that we came across this outdoor sculpture in an environment, it was also that it was an elk in its natural habitat. There’s something special about that. As opposed to running across it in a Chelsea gallery.

WK: Yeah, I have to agree. Whenever I try to photograph my sculptures against a white wall, they seem to lose some vitality. But photographing them outside is really challenging.

MH: Do you experience your work as an experience? And do you object to it being seen as an object? (haha)

WK: It’s funny, I have this ongoing issue where people are compelled to put Christmas lights and wreaths on my sculptures. It’s a pet peeve of mine. They wouldn’t do that to an Irwin sculpture, that’s for sure! I bring that up as an example of how people sometimes objectify my work. What’s interesting for me is when the buyer has an outdoor space that they want the sculpture to live in, and they also want to live with it. That spot on their property becomes a home for the creature, in a way. I like that because the people are looking to experience their home life in a different way or in a way that’s enhanced

MH: Maybe the deeper question is can we really control why people like our work? We make our work to express something in particular, but if someone buys it because they see something else in it, we can’t control that.

WK: Right, and we can’t control how they display it, either. I haven’t always been happy with how my sculpture is placed, and in one instance the collector grouped my sculptures with other artists’ sculptures in a way that I felt diminished all the work.

MH: I’m sure that biochemists don’t have these issues. Any regrets over the path you chose?

WK: No, I don’t think I could have been a scientist or a biochemist. I didn’t have the aptitude for it. But it has given me a framework for empirical thought, and evolutionary theory is the underpinning of how I see the natural world. Making art is different than science in that it allows for an expression of how I see the world, and making art is the connection that I seek. I don’t know that I could have found that in a regular job. The creative life is something that I need and thrive on.

MH: What’s the best part about being an artist?

WK: Those moments when you’re working in the studio and the flow is happening, and the piece is magically taking shape. To me those moments are exquisite and wonderful, and you feel truly alive when they happen. And then knowing that you have that possibility within you is a lovely thing. There are a lot of trials and tribulations to being an artist, but when you realize that you have this thing that you can do, that you can make something out of nothing, it’s magical.

Wrought Taxonomies is an exhibition of the artist’s outdoor sculptures and works on paper at the Suffolk County Vanderbilt Museum in Centerport, NY. It opened on Earth Day, April 22, 2023 and will close on April 22, 2025.

* * *

Uprising is an artist residency and solo show at Big Arts, Sanibel Island, FL from March 15 - April 28, 2024. The exhibition will feature drawings, paintings, and sculptures of the local wildlife.

* * *

www.wendyklemperer.com