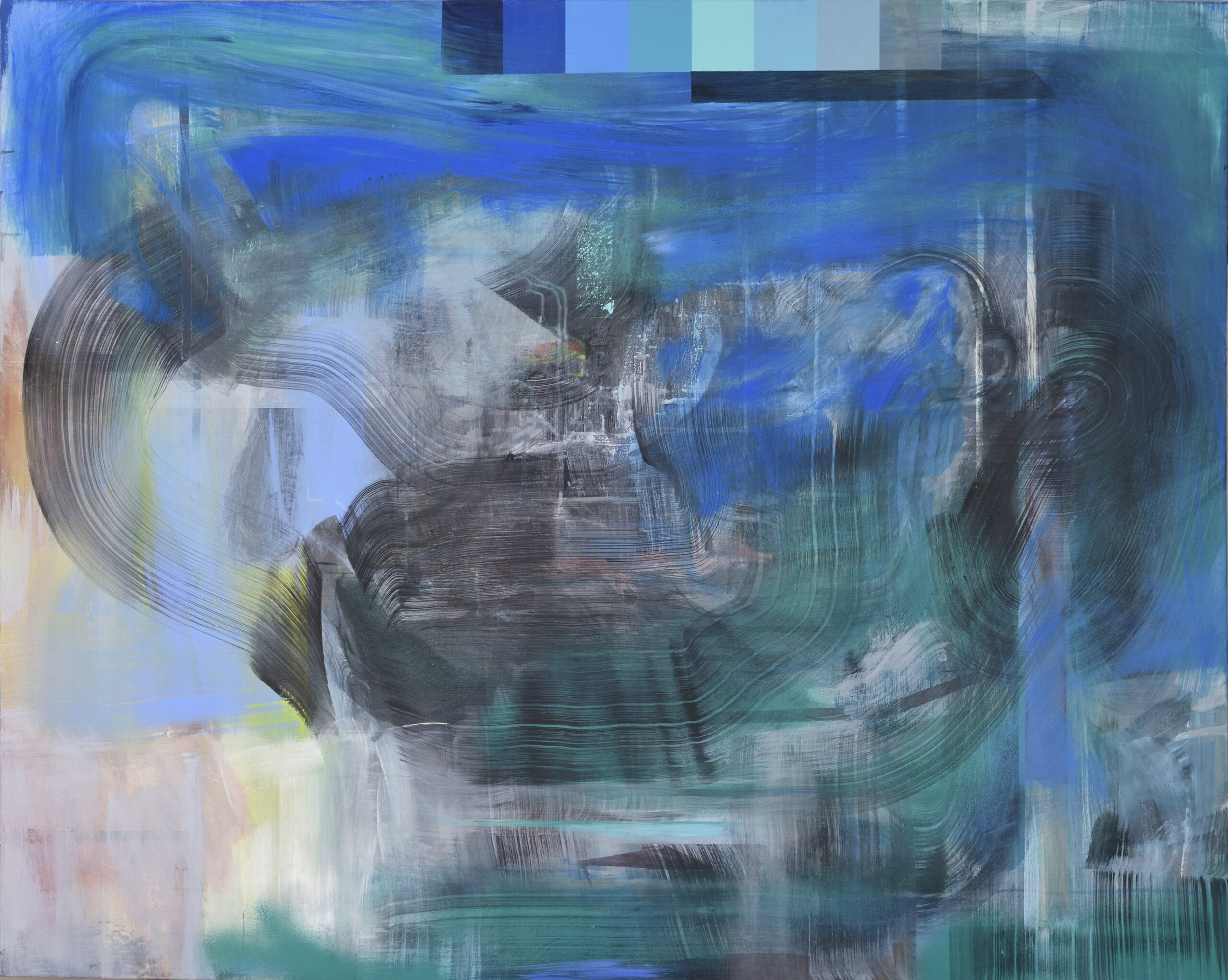

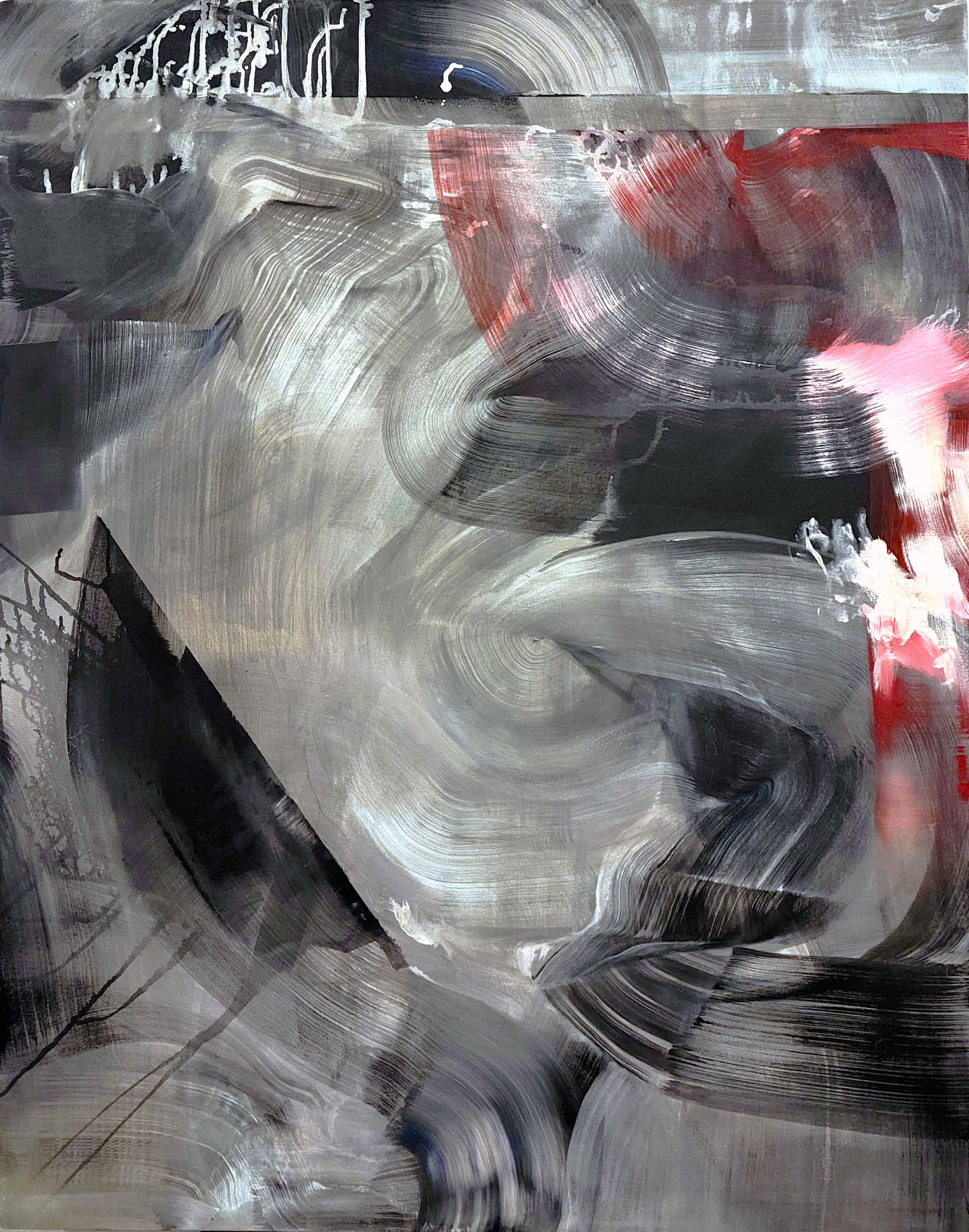

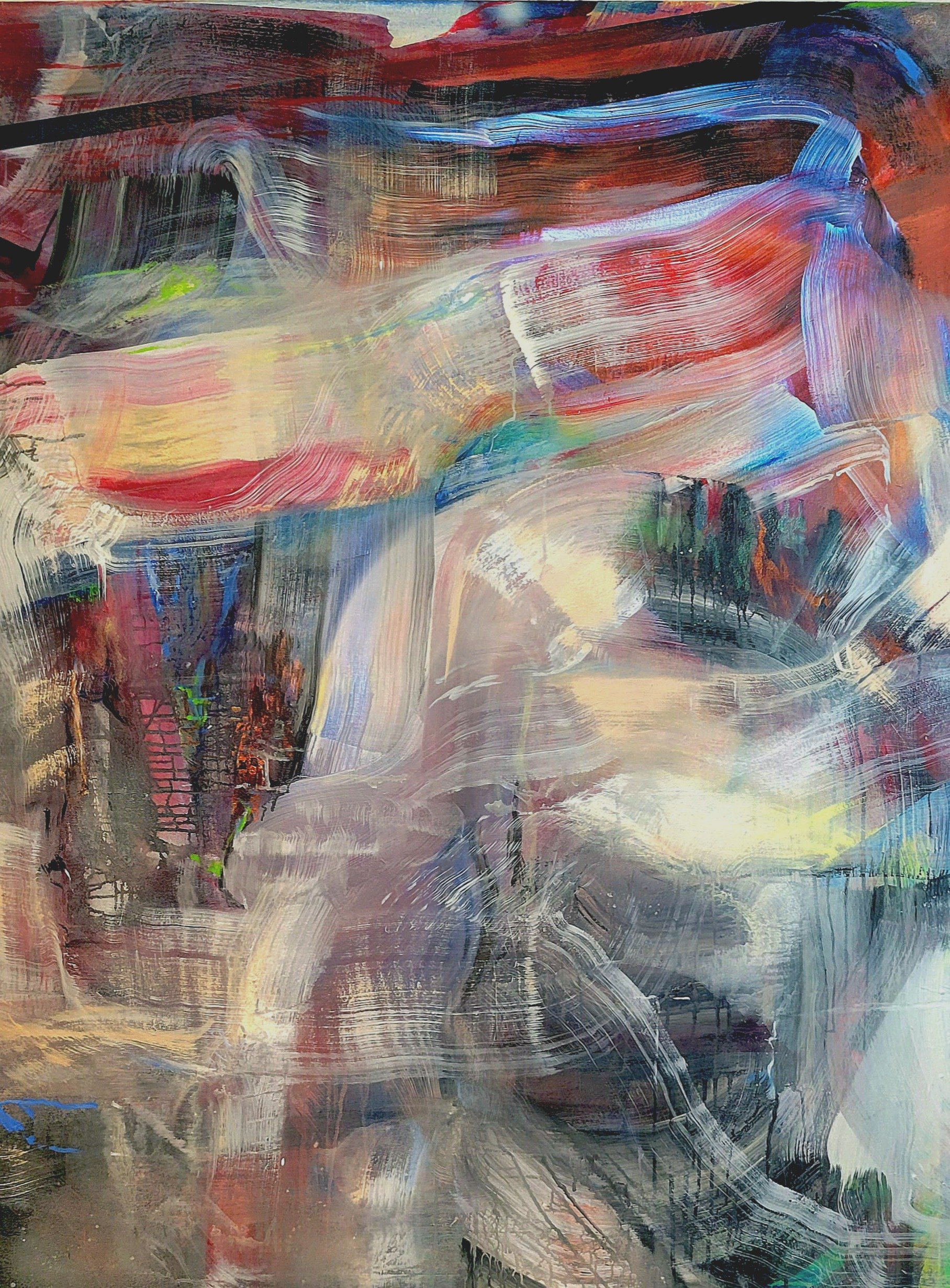

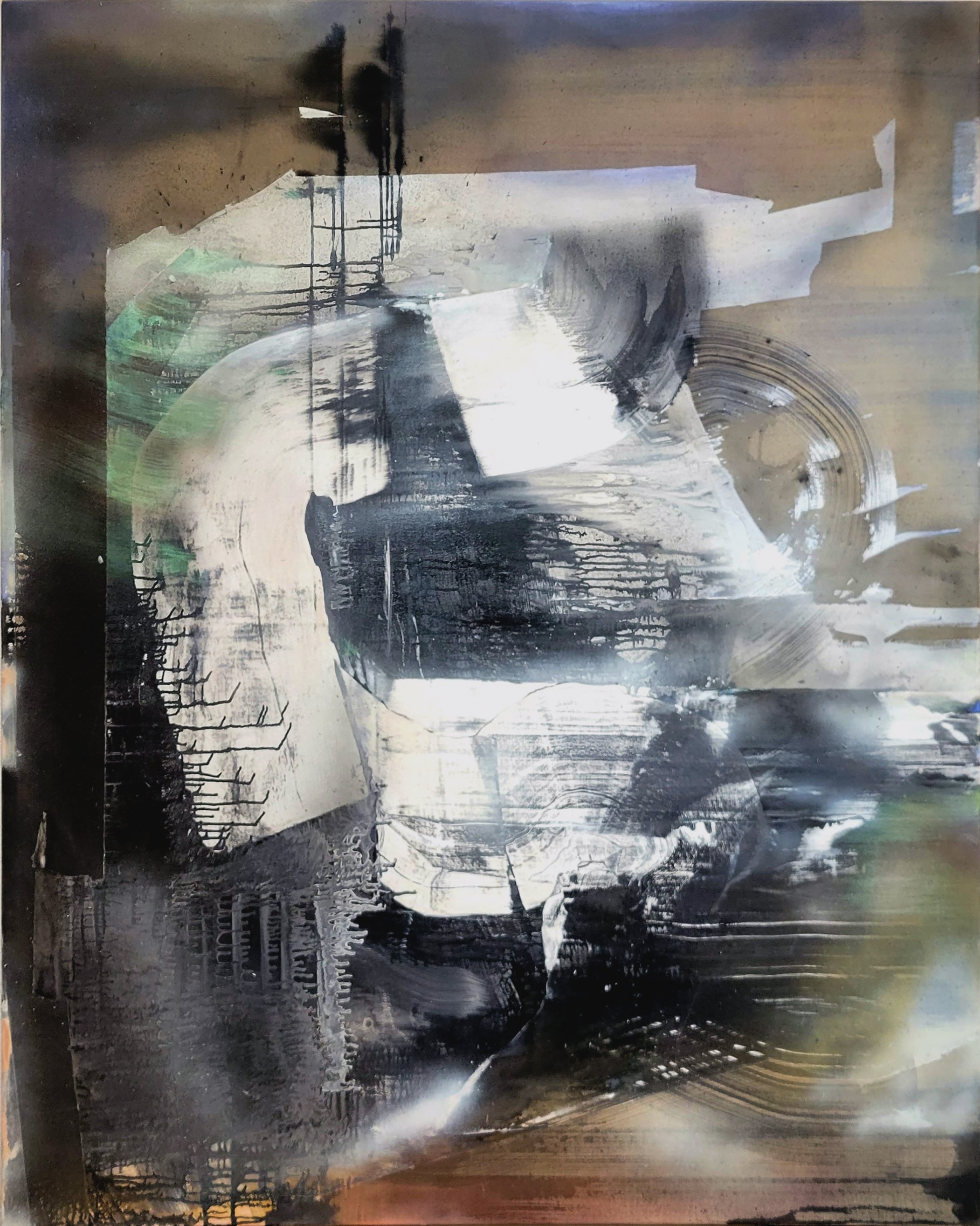

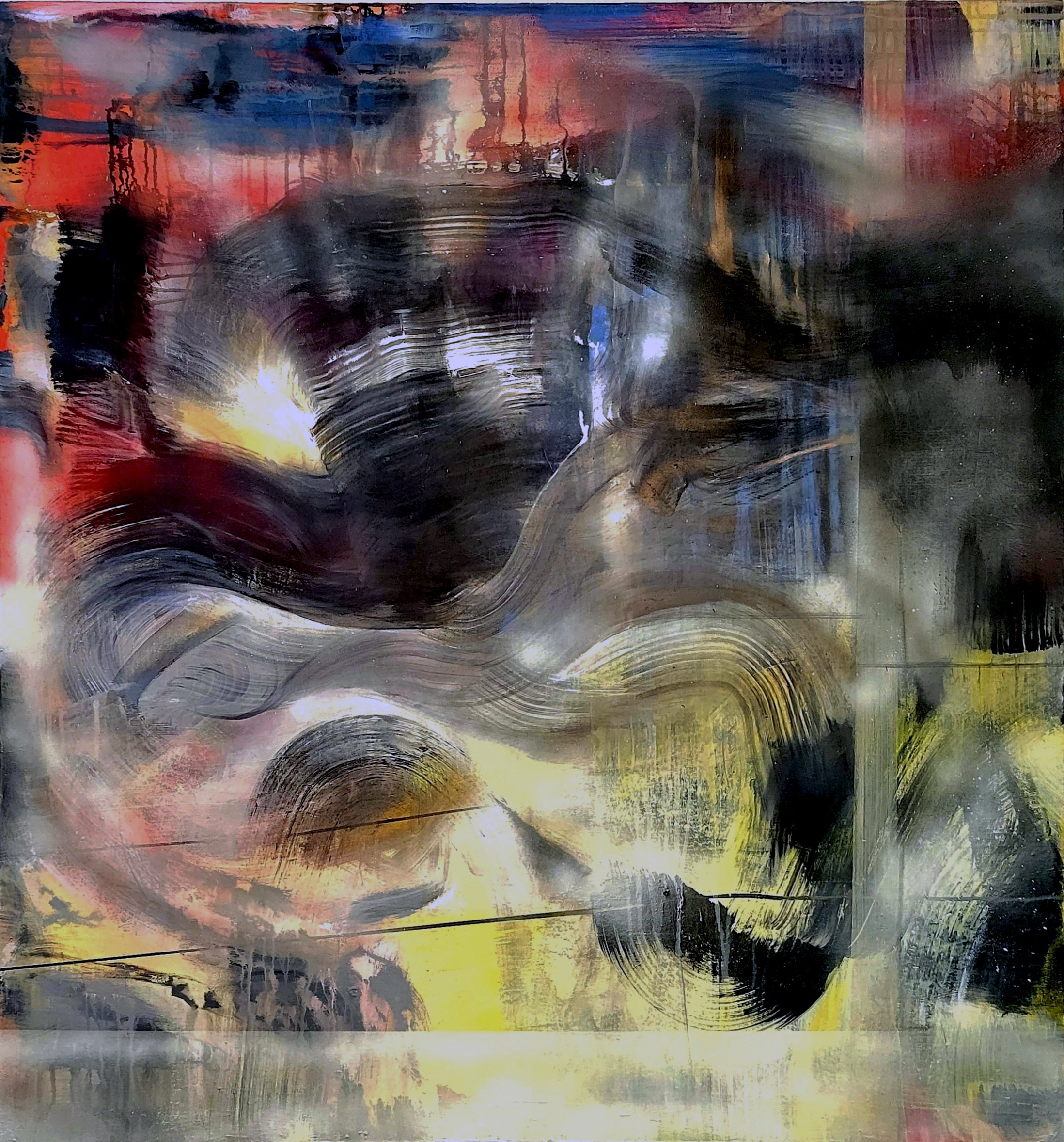

M Pettee Olsen’s sweeping brushstrokes are at once spontaneous and choreographed, suggesting a painter who confidently engages her whole body in the creative process. As a former dancer, she states that she’s painting the dance in her bones, infusing her large paintings with the grace and fluidity of motion that comes from years of disciplined training in ballet and modern dance. She uses a variety of paint media, including some with reflective properties, to play with luminosity, depth, and perception. Indeed, Pettee Olsen is interested in how we perceive the world, how we interpret it through our respective lenses, and finally, how we form narratives around our subjective experiences. These stories are passed on through oral tradition, dance, theater, and the myriad forms of storytelling through which humans tell their version of history. The discord arises when our narratives clash, often resulting in conflict and tragedy on a global scale. Pettee Olsen invites us to lose the stories that undermine meaningful connection and fuel dualistic thought. She superimposes value scales and geometric elements on her canvases, disrupting the painterly dance/narrative to introduce a more open-ended conversation. By letting go of self-serving storylines, we open ourselves to the common humanity that supersedes the desire for power, marginalization, and war. Pettee Olsen’s gestures are soulful and profound, but they can also be unsettling, as if reflecting our darkest self. The alternating shimmers and shadows in her paintings speak to the best and worst of who we are, as our stories realign to narrate a more faithful portrayal of ourselves and the human condition.

MH: You paint with acrylic on large canvases, using extra-wide brushes and bold, sweeping strokes. Has this always been your style, or did you just bust loose one day?

MPO: I’ve always worked on largish canvases because of the nature of how I paint, which comes out of dance. There’s a different kind of sensibility that happens when I’m making a sweeping gesture compared to when I’m working small. It moves from a kinesthetic level to a more intimate movement of the hand, and it comes from a different place in my head. But I also use smaller brushes when I get to the more detailed mark making in my paintings.

MH: How do you see your work in relationship to Abstract Expressionism? Does the comparison make you cringe, or is Ab Ex your tribe?

MPO: Obviously there are roots there, but anytime someone places you in the past is not a good thing, and yes, it can be cringeworthy. I don’t think about my work in the studio as Ab Ex because my intentions with my work are so different than what they were after. Also, I use reflective pigments that read differently from different points of view. That is not a tool set the Ab Ex artists used, and it distinguishes me and places me squarely in the forward-facing present.

MH: You were on track to become a professional dancer when you were younger but had to stop due to physical issues. Were you already a painter at that point? Or did you turn to painting when dance was no longer an option?

MPO: I was taking company classes with American Ballet Theater when I was in school and to me, this was the company to be with. My teacher was from Odessa, and I got so much from her, that sense of love and passion for the arts. Visual arts were also an important part of my life back then, and I had a portfolio of drawing and painting toward the end of high school. So when I got injured and the dance thing fell apart, I fell apart with it, and it was then that I knew that I’d go to art school.

MH: If you’d never studied dance, do you think your paintings would be what they are now?

MPO: Probably. There was always a part of me that was interested in going beyond the physical into the psyche, and on some level the dance took me there. But I always knew that I was searching for something else, a tool set that lived a lot longer than the brief career of a dancer.

MH: When you told me that you were a dancer, your paintings came to life for me. A dancer uses her body to make graceful, sweeping gestures, which is exactly what you do in your paintings. How do you regard your painting process in relationship to dance?

MPO: It’s funny, whether you’re a painter or a dancer, you go into your studio to engage in this physical process. People say that the body is in my painting, but I have more concerns with time and space, self and no-self, than I do about the body and dance. There are beautiful gestures in my paintings, but I also want there to be a foil against that, so I add rectilinear elements that are about thought and other interruptions. So I’m compressing spontaneous and choreographed moves into flat space, and in the process, I’m painting the dance in my bones, a choreography that’s 3.7 billion years in the making, and filtered through my distinct lens.

Falling Away, 2022, synthetic and luminous paint on canvas, 60 x 144 in. (triptych)