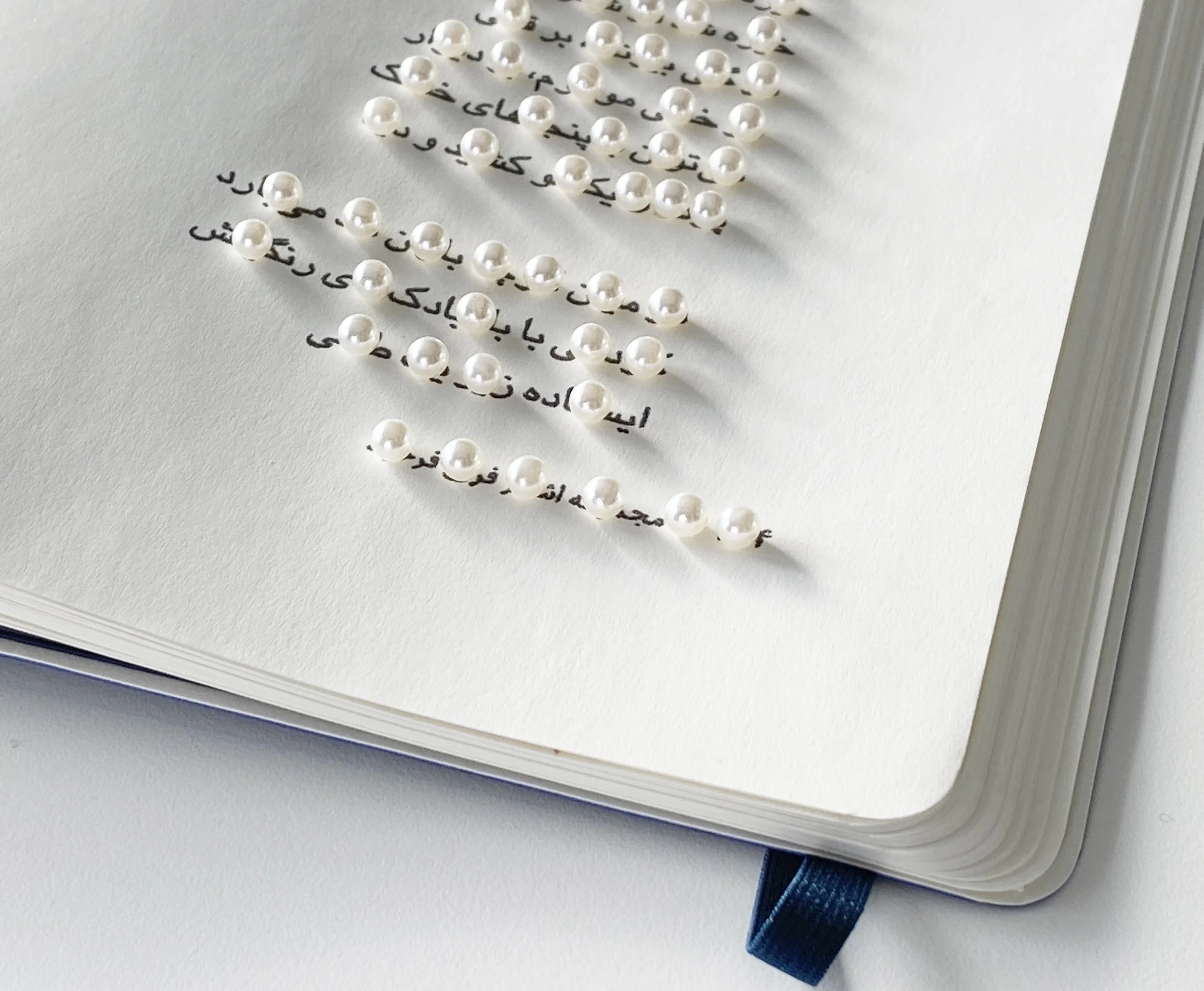

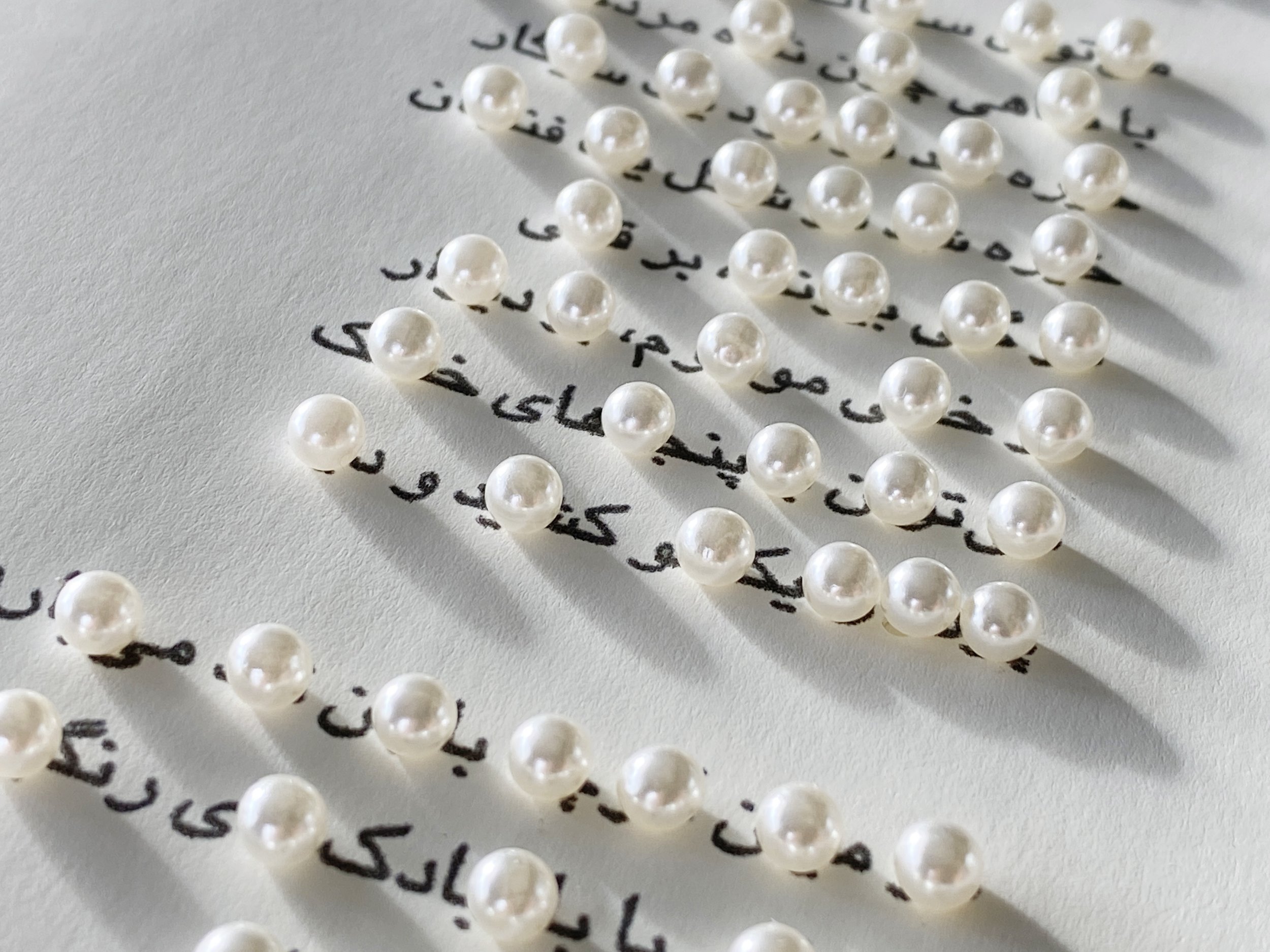

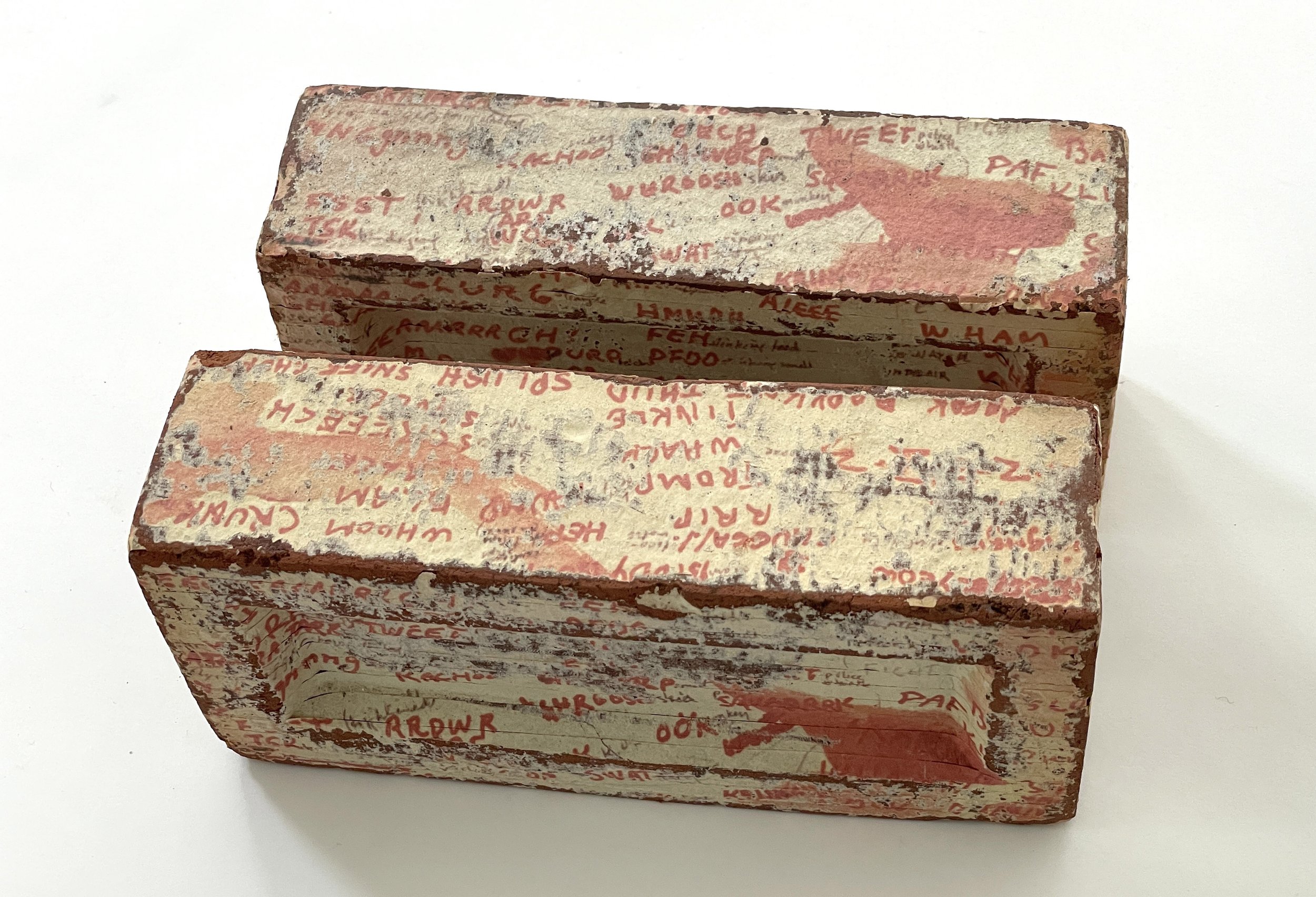

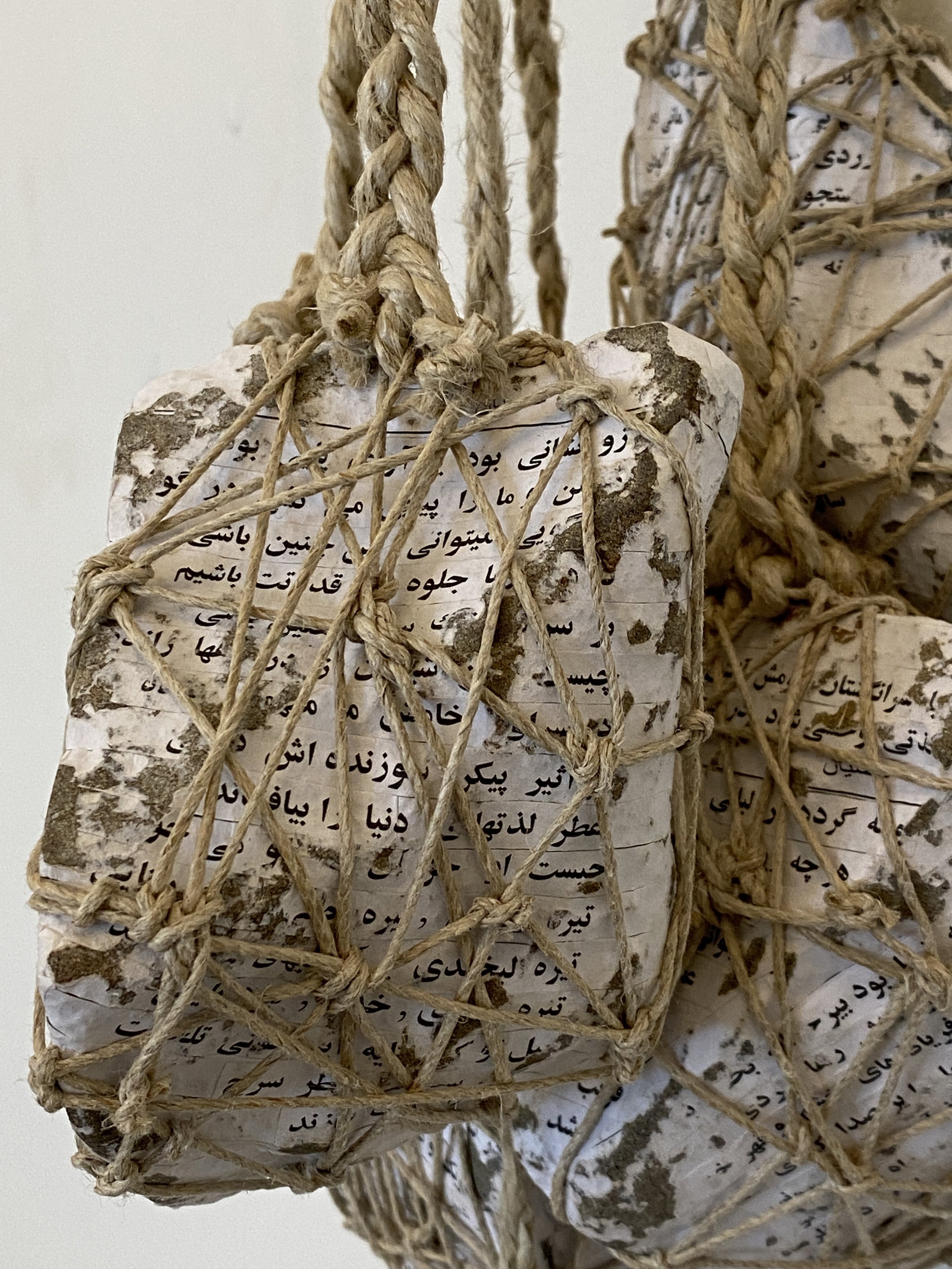

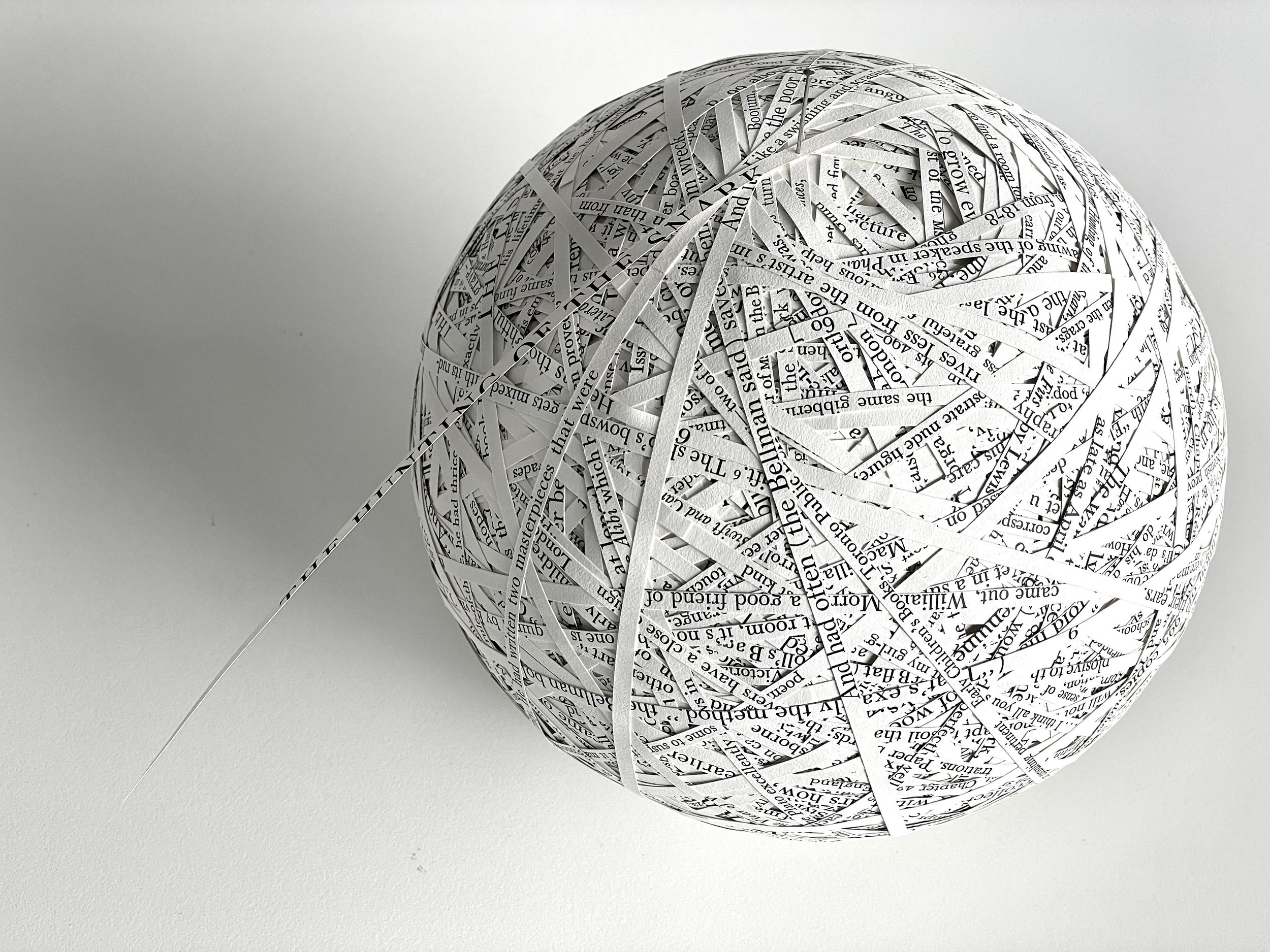

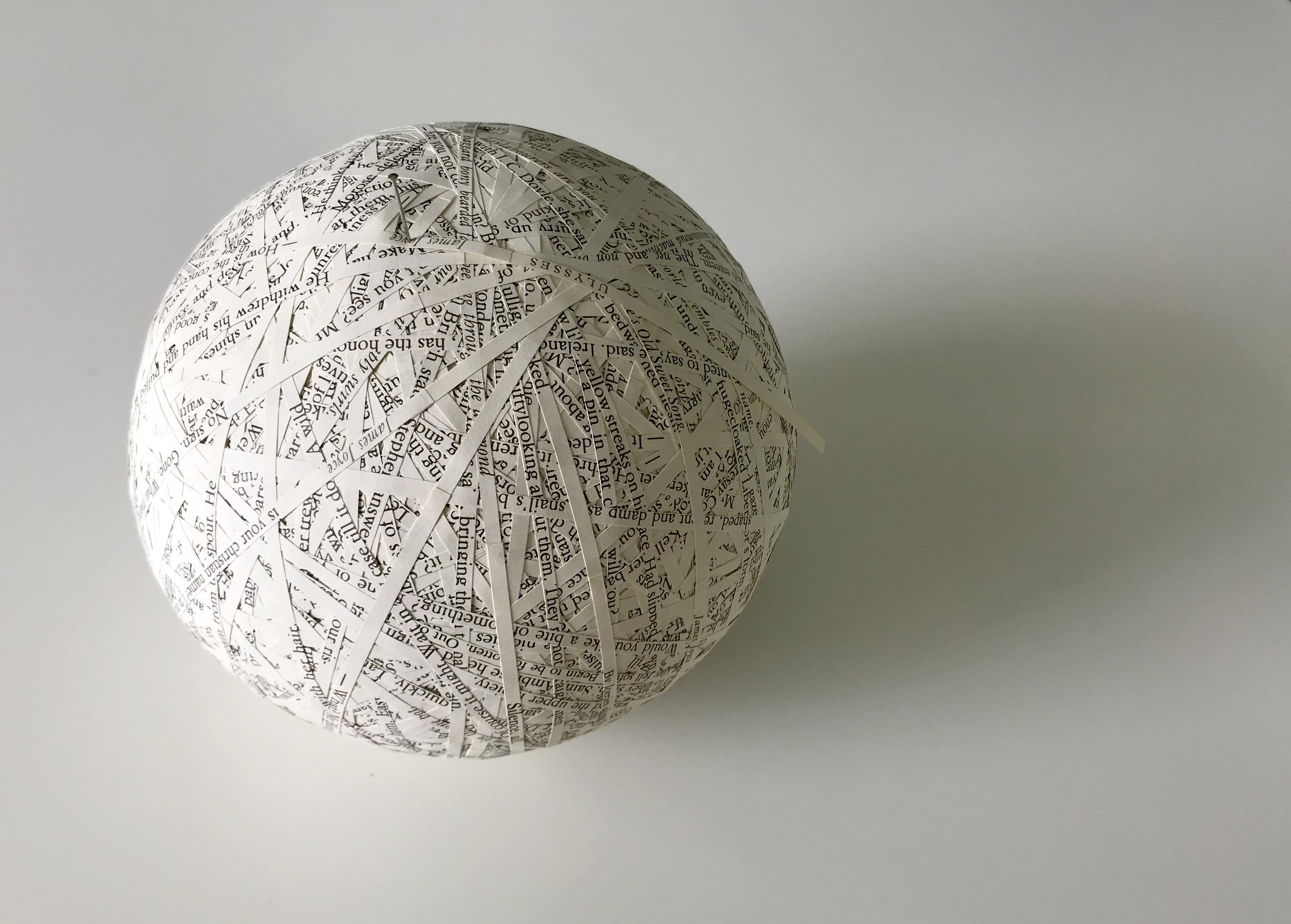

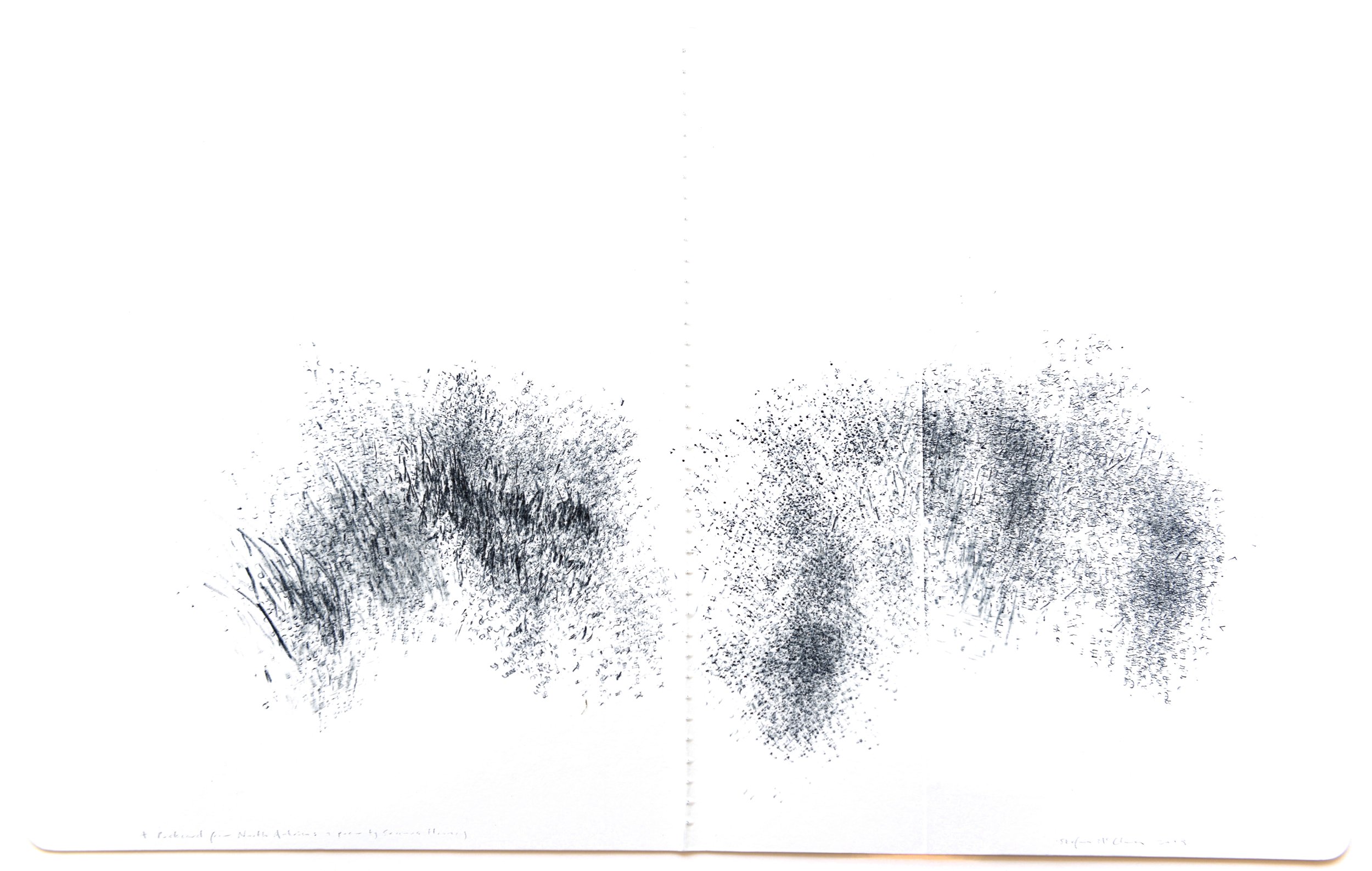

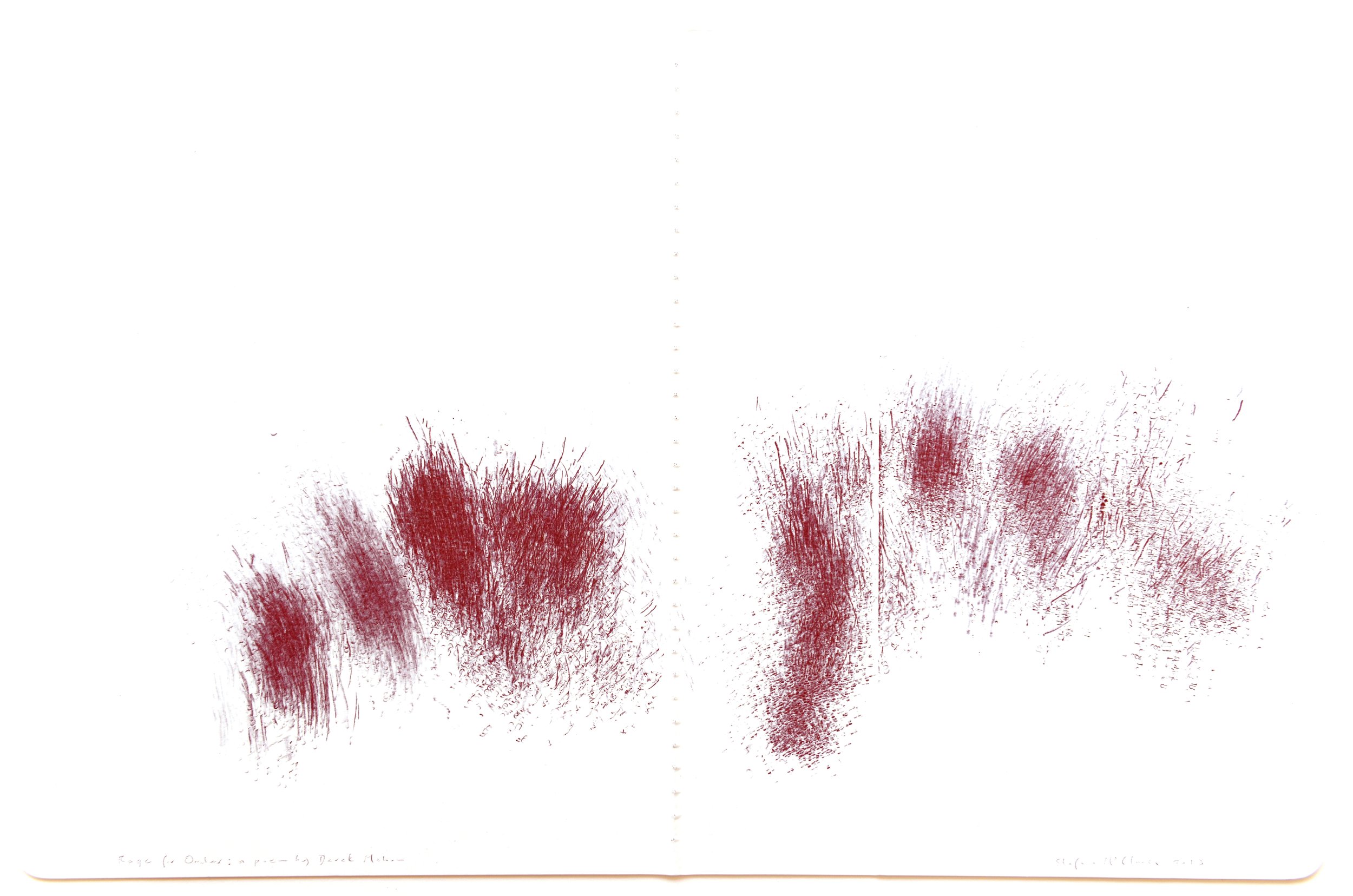

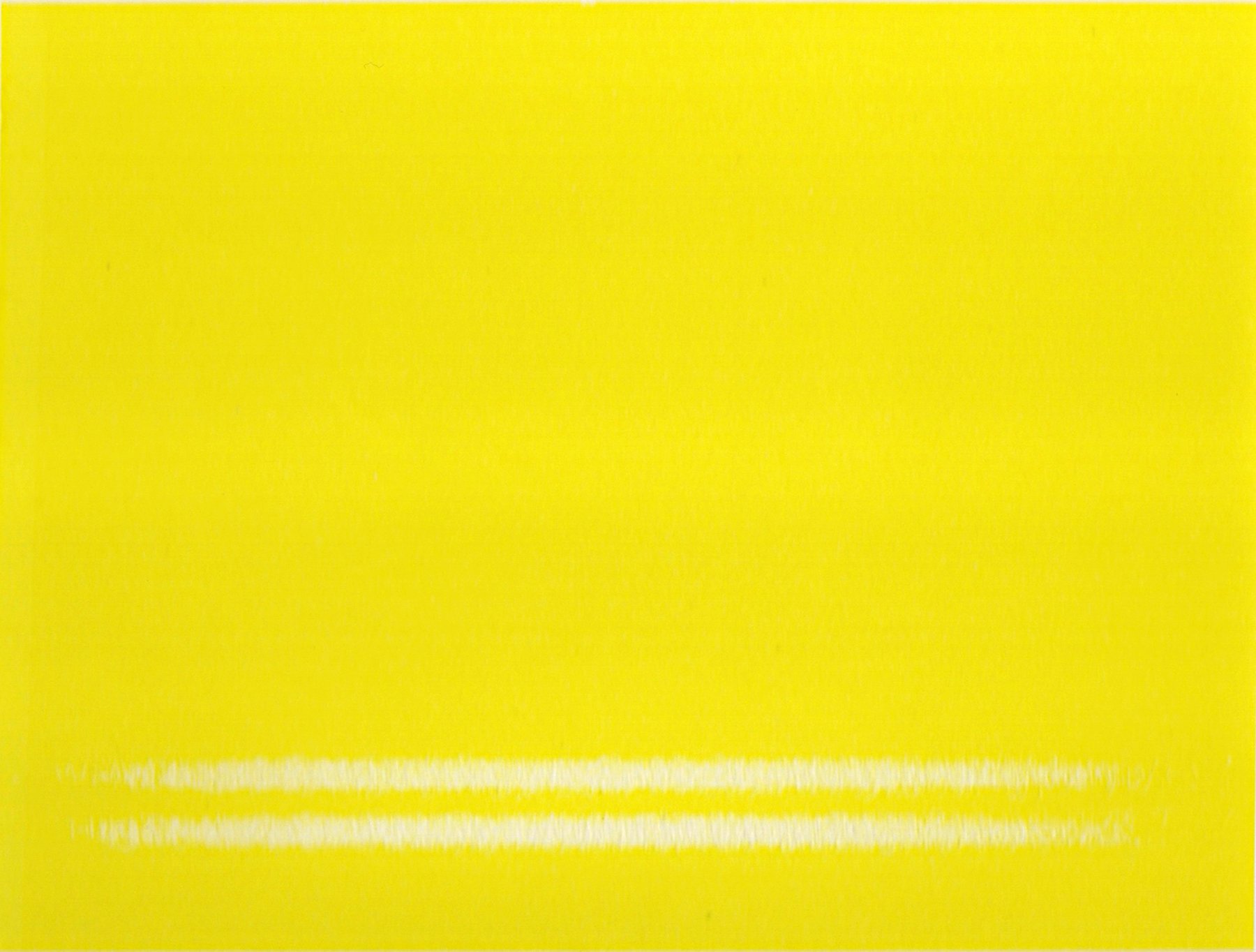

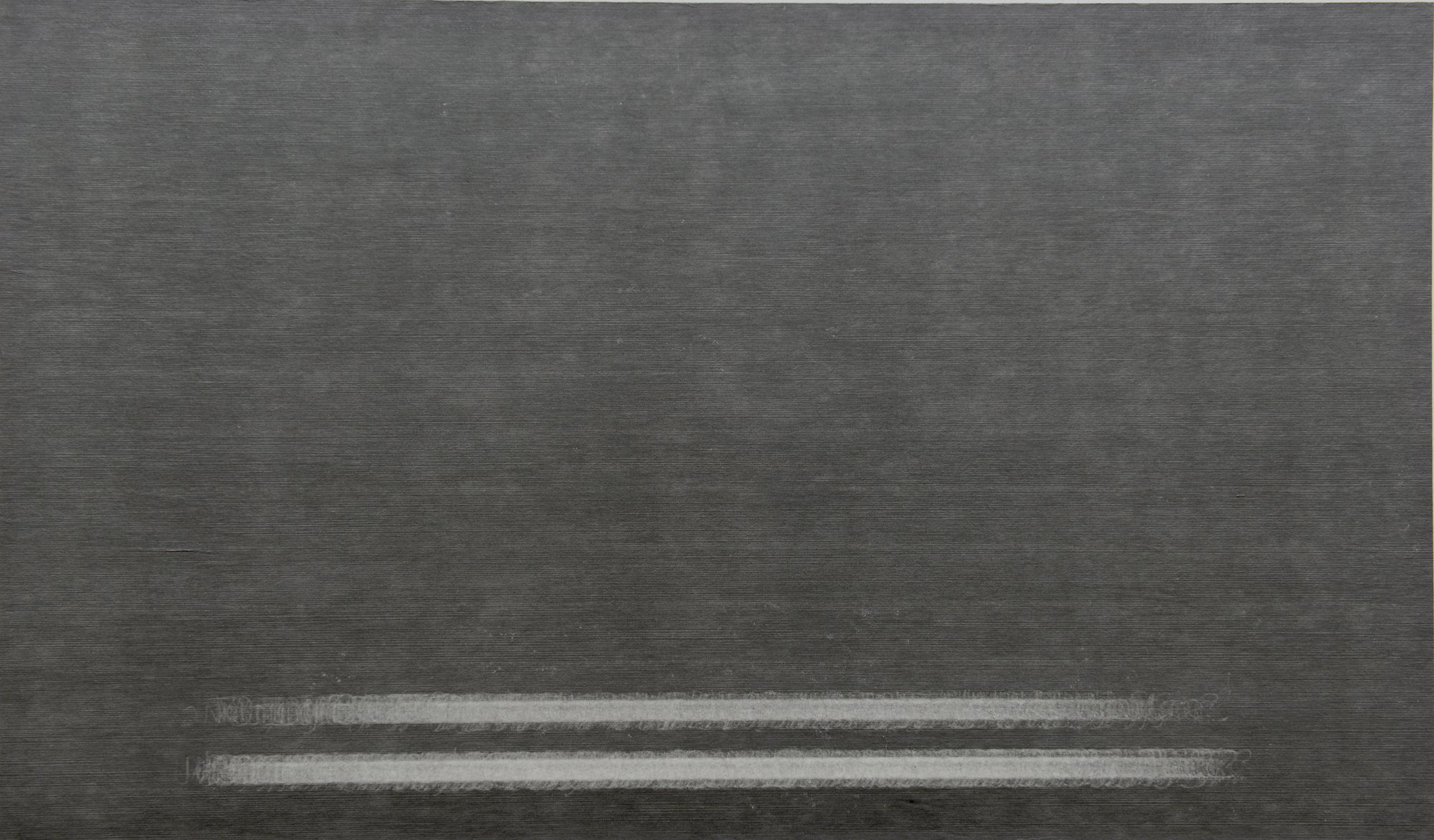

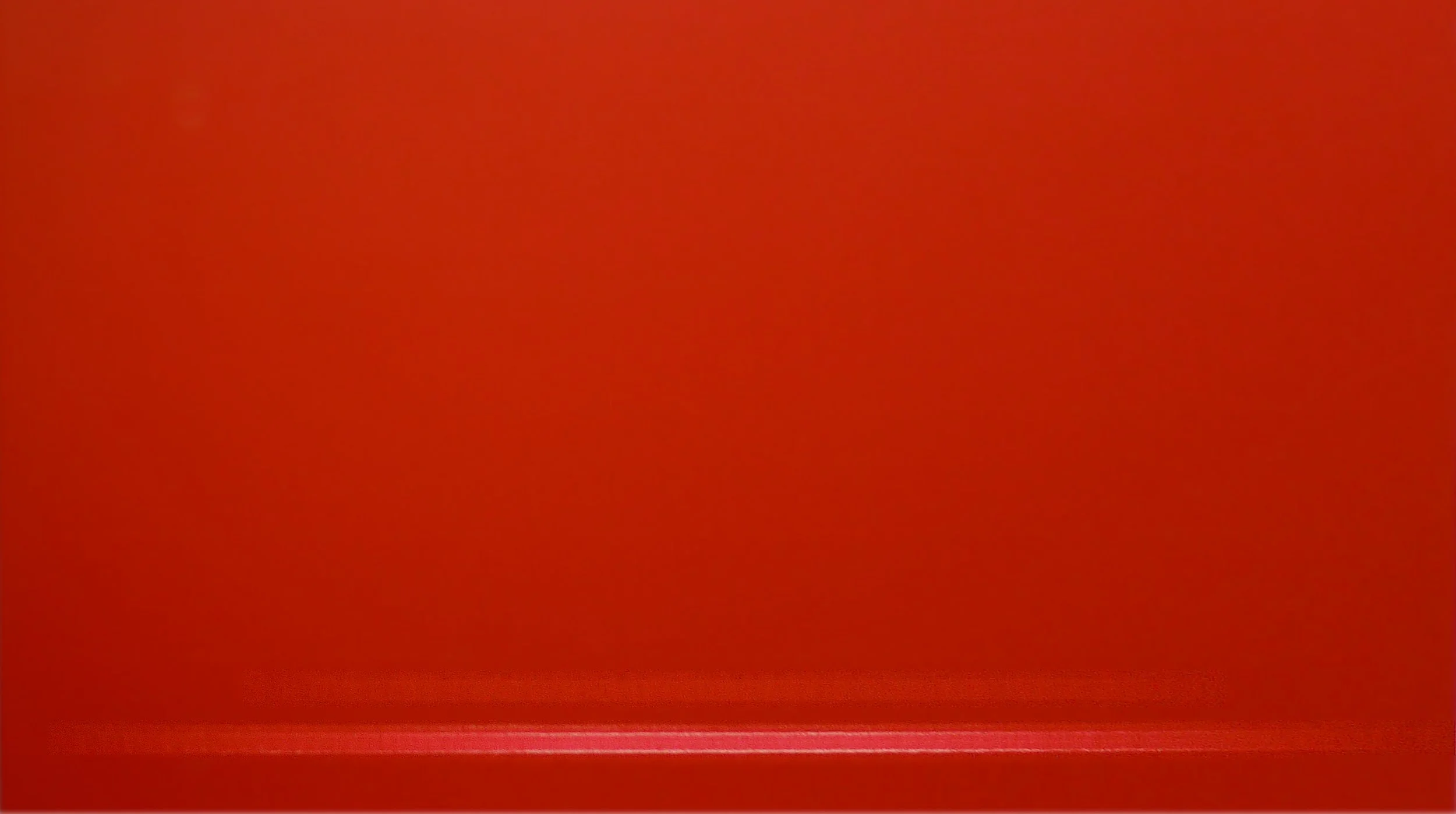

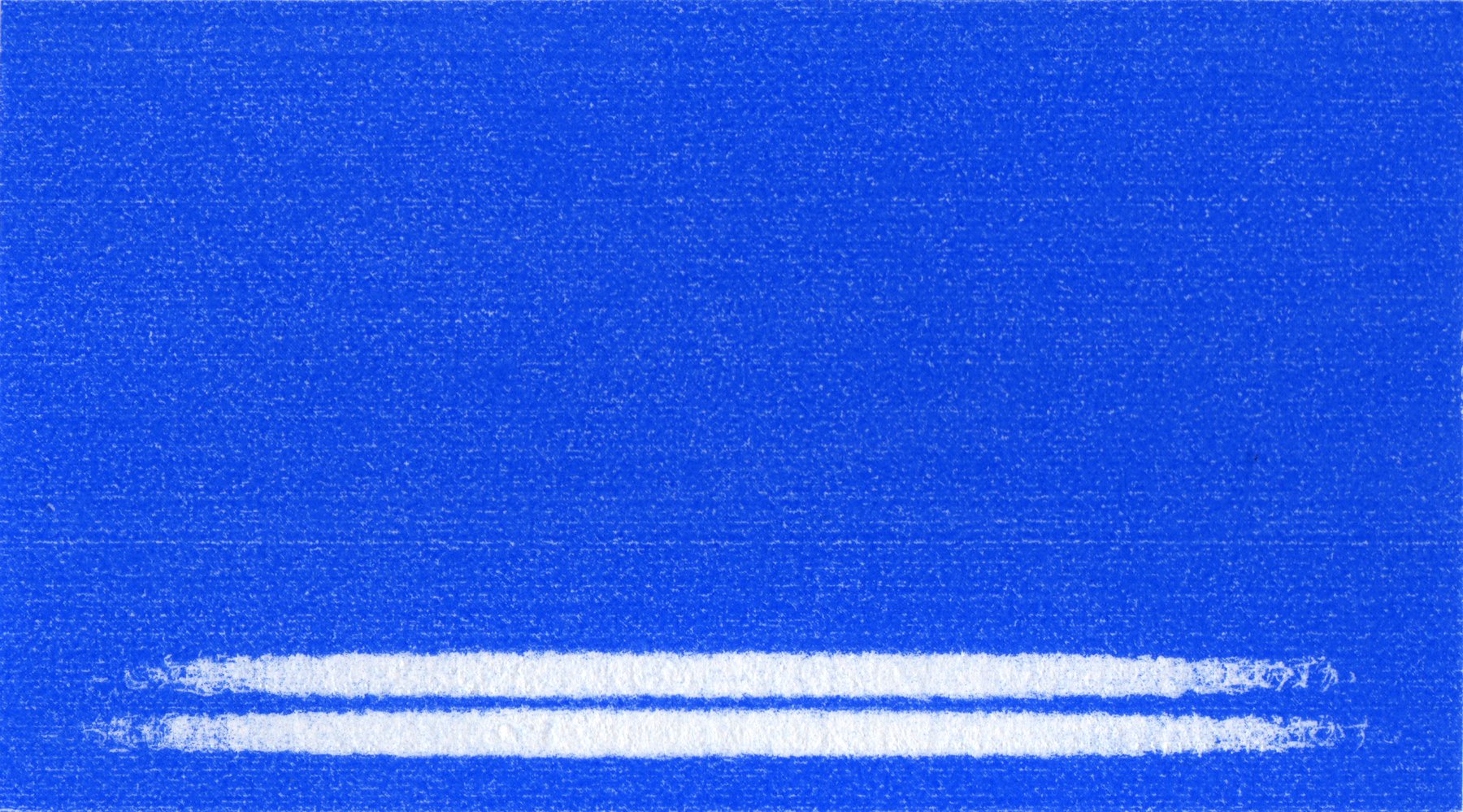

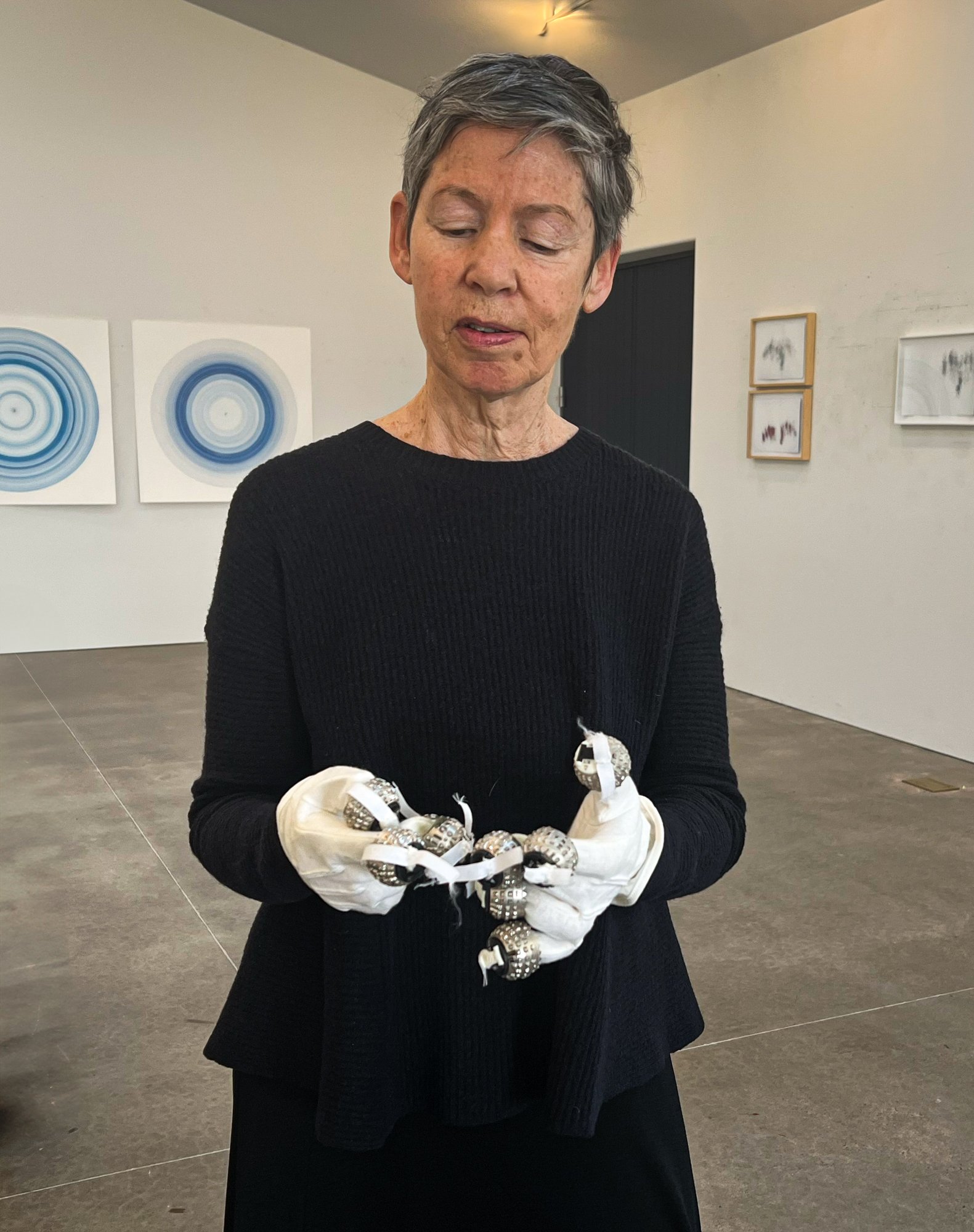

Stefana McClure works with text in the way that a painter works with chiaroscuro, contrasting light and shadow to create psychologically dense works of art. The first time I encountered her work I was moved by the painstaking skill involved in slicing and knitting the thin strips of paper. As I spent time with the individual pieces [see images 1-3, above], a dark presence slowly emerged, casting its shadow across the intricately woven text. I later learned that they were made from government documents obtained and released by the ACLU, detailing the “enhanced interrogation” techniques used by the CIA on Iraqi and Afghan soldiers. The black ink was redacted text, adding another layer of shock and revulsion. The stark juxtaposition of the exquisite and horrific is a recurring theme in McClure’s work, as she uses language and writing to express the complexity and capacity of human nature. And what better medium to convey its inherent contradictions? McClure finds poetry in the threat of violence when she wraps her Protest Stones in feminist verse, admittedly pointless when you’re on the receiving end of the stone, but wry humor is another important aspect of her work. Indeed, McClure is self-deprecating when describing her process, and is quick to poke fun at the absurdity of her time-devouring studio practice. In her words, “It’s serious work, but it doesn’t take itself very seriously.” She spends weeks and months extracting exhaustive information and condensing it into a single piece, as she does in her Films on Paper. In this series, inspired by her love of foreign films, she copies the subtitles, including the typos and clumsy translation, and superimposes them on a monochromatic field, positioned as on a television screen. The writing is illegible, but carries the energy of the film, just as her wrapped novels carry the intent of the writer. McClure’s love of language is visible in every work, and her fluency in Japanese, as well as her time spent as a translator and interpreter, give her a unique insight into the gap between languages, where much of meaning is lost. McClure doesn’t seek to eliminate the gaps, nor does she deny the threat of violence that is present in much of her work. Instead, she seems to embrace the fissures that exist between cultures and within our collective psyche. McClure’s appropriation and reconfiguring of literature allude to some of our greatest achievements, while humbly acknowledging the darker aspects of humanity.

Stefana McClure