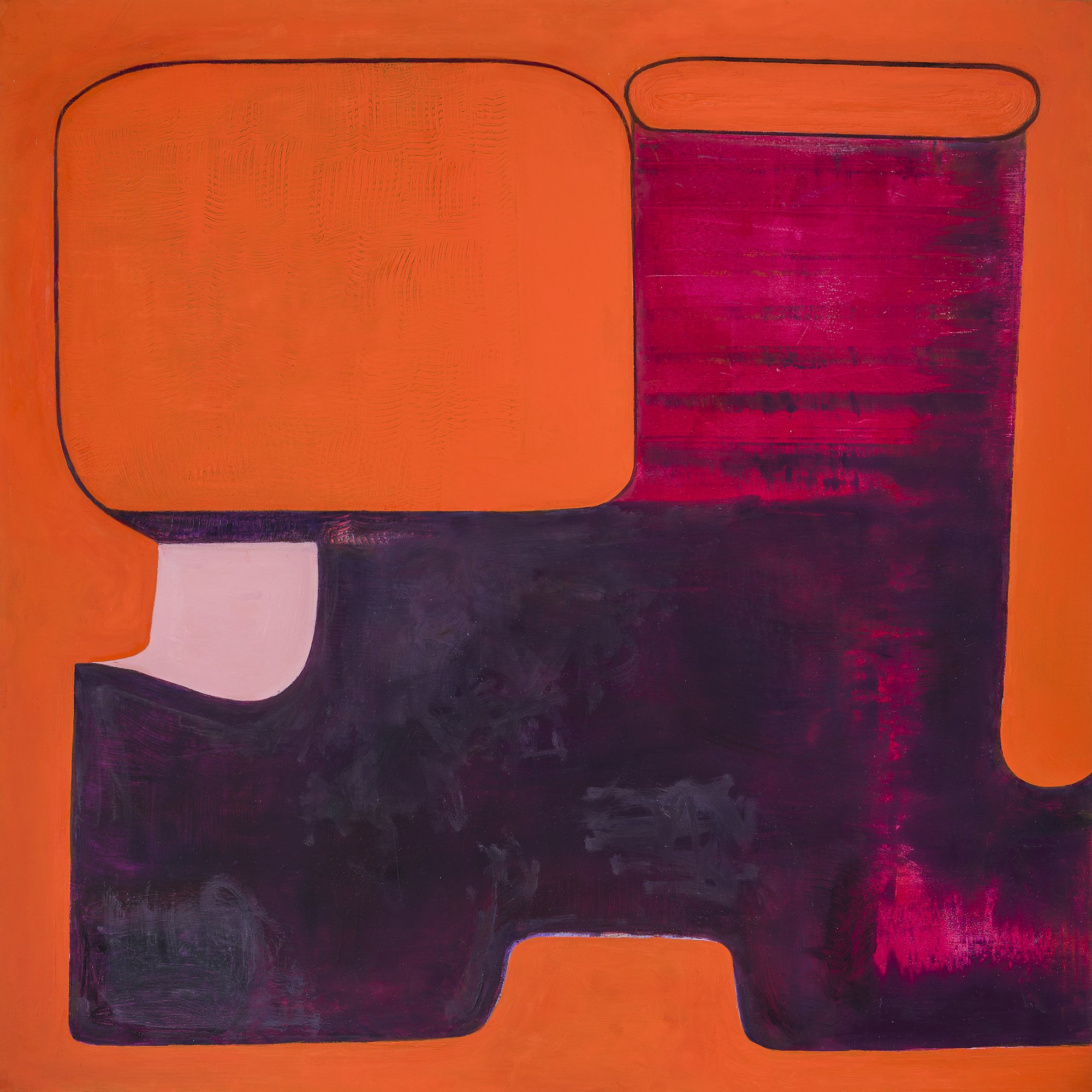

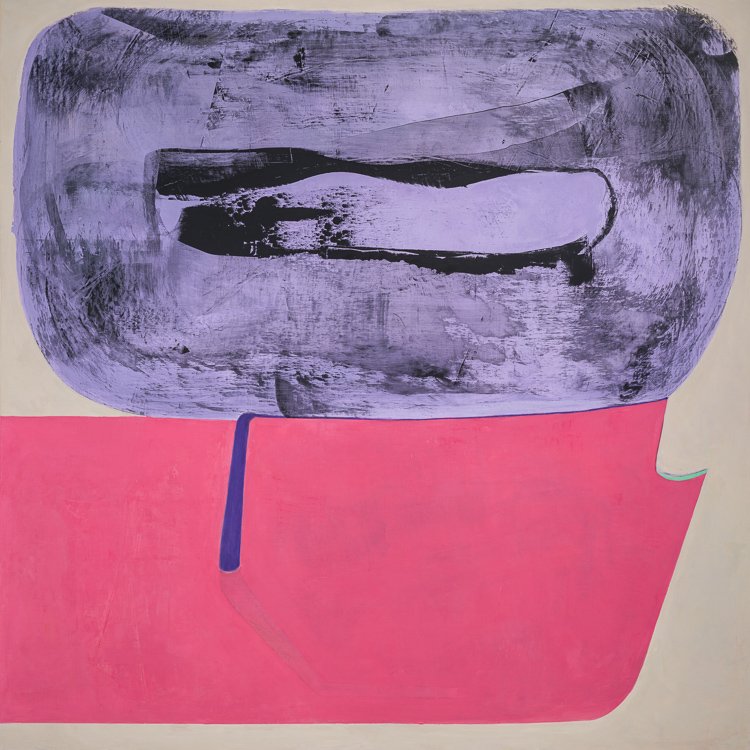

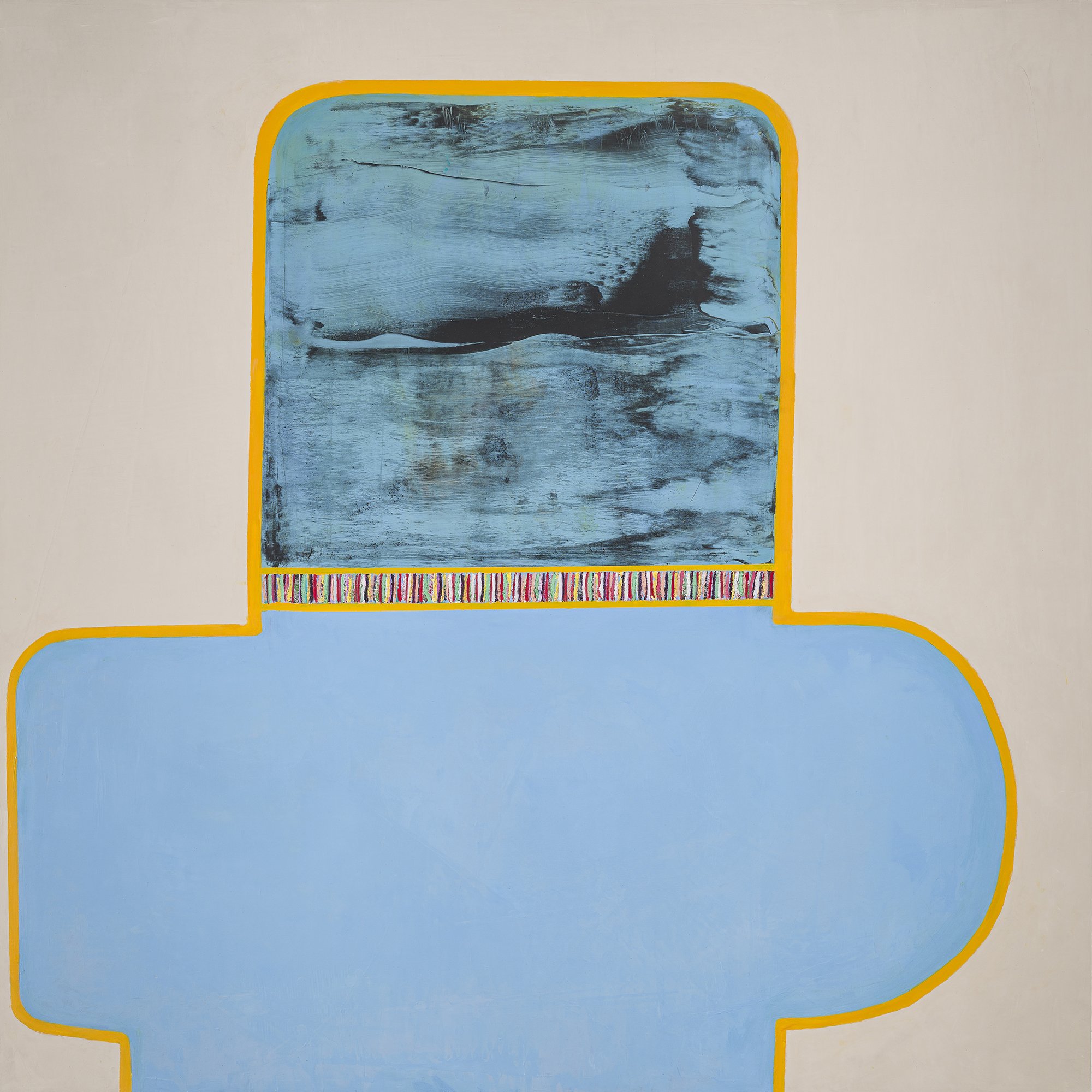

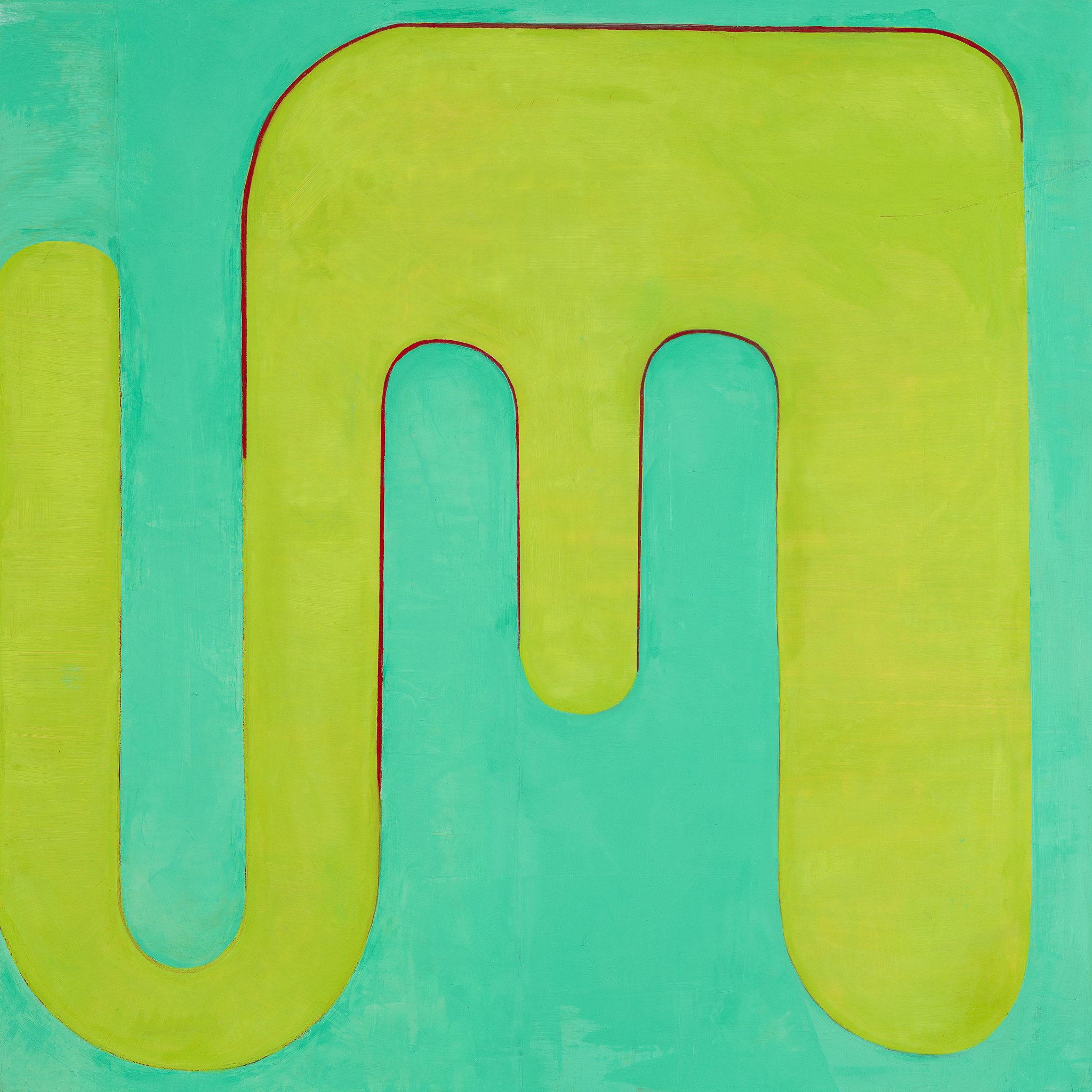

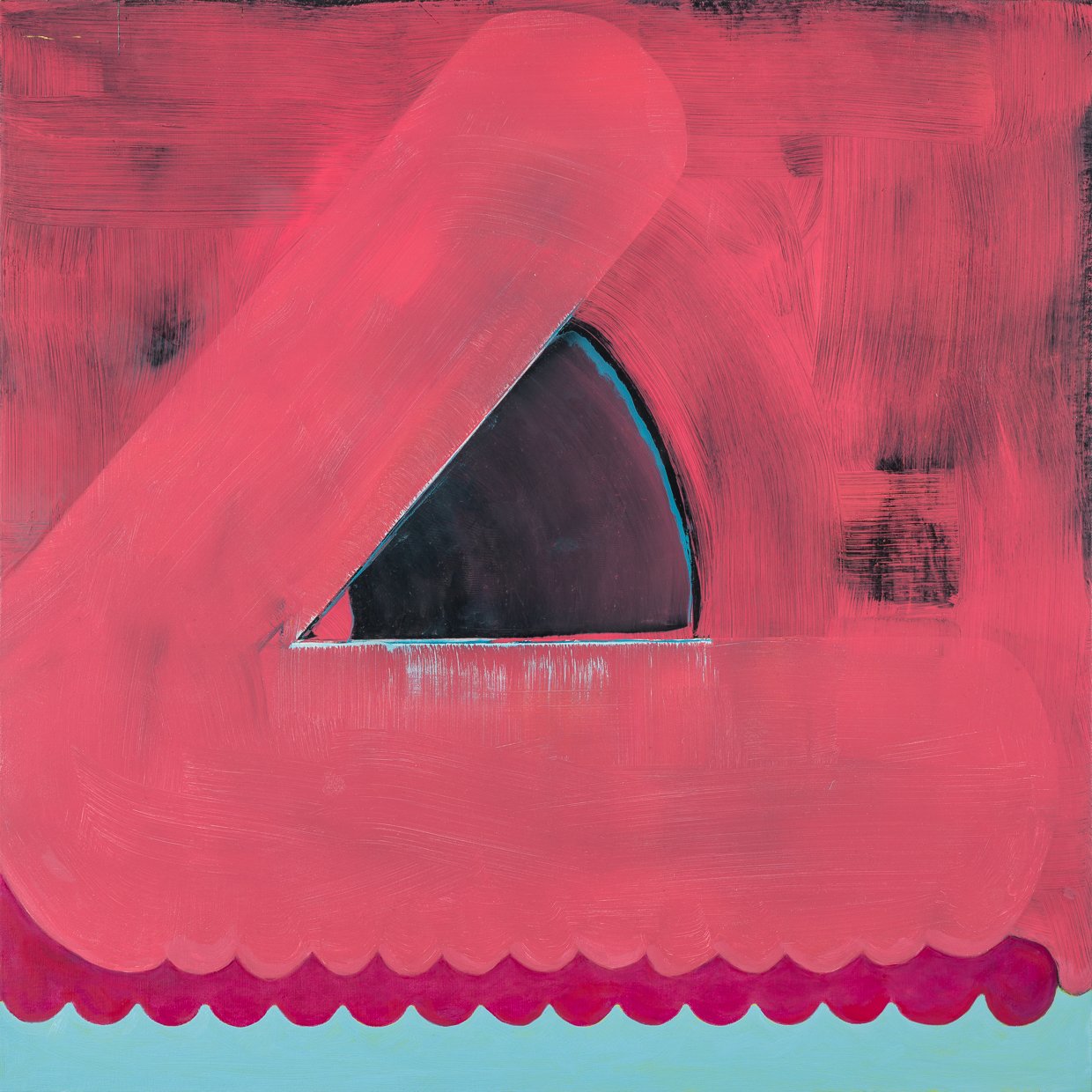

The abstract figures in Fran Shalom’s paintings seem complete and inevitable, as if born fully formed and ready for action. In truth, they are the result of a long birthing process in which Shalom reacts to her previous marks, adding or subtracting paint as needed. Her process-oriented work is based in a Zen Buddhist practice in which she responds to each moment without premeditation, allowing the existing brushstrokes to inform her next move. This unusual blend of spontaneity and inevitability creates a tension that energizes the figures, as if they want nothing more than to interact with each other and with us. It’s quirky that Shalom regards these forms as figures, but what else could they be? The absence of anatomy in no way diminishes their presence; we are captivated even without an accompanying narrative. This lack of context creates a vacuum that we rush to fill, imposing our affections and aversions on the figures as if ours was the only interpretation. But Shalom seems to ask us to withdraw our projections, just for the moment, and experience her paintings as she does, with a fresh eye and an open heart. Her process requires that she fully engage not just in each painting, but in every brushstroke and breath. Shalom is a painter’s painter, masterful in the art of improvisation, but her greater gift is to inspire us to drop our ongoing narratives and directly experience the present moment, without judgment or attachment.

oOo

Fran Shalom’s solo show Taking the Backward Step runs through December 2nd at Kathryn Markel Fine Arts.

oOo

MH: Your paintings consist of bold, abstract shapes that appear to be solid and complete, as if they were born that way. Do you have a vision before you start painting, or is it always a process of discovery?

FS: It’s mostly a process of discovery. I never start out with a drawing that I’ve created beforehand, but I have shapes that I gravitate toward. It’s just a matter of getting something down on the panel, and then there’s a conversation between that and what I do next. It’s all in the moment, but I’ve been painting long enough that I know something will appear that I can work with.

MH: Your paintings don’t have a cookie cutter look. I get the sense that each painting is a journey or discovery.

FS: It is, and sometimes I worry about the work not being consistent enough. I don’t think in terms of series, but there’s a underlying consistency that comes through so that’s what I’m hoping for.

MH: When you start a piece, are you confident that you’ll get it to the place where it’s a good painting?

FS: It’s a great question. I’ll start a painting and get to a point where I think to myself, this isn’t working at all, I don’t know what I’m doing. Then I’ll change something that maybe I was attached to, and it starts to work. So I’m fairly confident that I’ll get there, and that I’ll come out the other side.

MH: The shapes are very satisfying, in part because the negative space is so well defined. Are you thinking about the figure/ground relationship as you work?

FS: I do think about it, maybe not as much as other artists, but the figure is very important to me. The negative space becomes a shape in relationship to the foreground shape, and it’s harder to come by than it looks. The figure needs to be located in the composition in a way that feels satisfactory, then as I move toward its resolution, I become more aware of the play of figure and ground.

MH: You refer to the forms in your paintings as “ambiguous characters who inhabit my studio and keep me company.” You must have a very large studio [haha]. What do these figures represent to you? Are they your allies?

FS: They’re definitely my allies. Over the years they’ve become different things, but I love the conversation with them, and I feel that some of them want to be named or identified. There was a famous psychologist, Philip Bromberg, who talked about self-states, which are different parts of ourselves that we may have disassociated from. We need to recognize and become friendly with our self-states, and in some ways that’s how I think of the figures. It’s a relationship that feels very comforting, as if they’re my companions.

MH: They seem vulnerable to me, and maybe a little anxious. It’s like they’re aspiring to be human but keep missing the mark. I’m curious why you avoid making them more representational?

FS: I started out making abstracted heads years ago that were influenced by my son who was 3 or 4 at the time. He was constantly drawing these very simple heads and figures, so I started thinking about how minimal I could be and still have it be recognizable as a head, without eyes or features. My paintings are always on the verge of becoming more literal, but when they get too suggestive, I get a little nervous and I want it to be more abstract. I don’t mind the back and forth, but I’m not interested in painting representationally.

MH: Do they evoke compassion for you? They do for me.

FS: Oh good, I’m glad to hear that. Yes, there’s compassion, calmness, satisfaction, and I have a relationship with them, like every artist has with their own work. It’s very satisfying.

MH: Your artist statement cites a reference to Zen Buddhism, and I know this is one of your primary influences. How do the Zen teachings show up in your work?

FS: They show up in the practice more than in the painting. For me it’s about being with the canvas and just trying to be open to whatever mark or shape I put down, then I play with it for a little bit and start responding to whatever’s there. There comes a time later on where I pull back and criticize and make the necessary changes, and that’s really important and healthy. But in the beginning, you just have to get out of your own way, and that’s very Zen.

MH: As a Buddhist practitioner, can you distinguish between a “good” and “bad” painting? Or would that judgment be considered antithetical to Buddhist philosophy?

FS: It’s not antithetical. We all have likes and dislikes and preferences; that’s how we function in the world. Buddhism is not about being on another plane, it’s about practicing and being on the cushion and then taking that practice out into the world. Buddhism is about the ordinary mind, not an exalted state; it’s what you encounter every day in your life. But I don’t think it’s a good idea to judge a painting as bad, because that obstructs the process, and you start working against yourself.

MH: What does a successful painting look like through a Buddhist lens? How do you step outside the ego to make that determination?

FS: Yeah, it’s hard. Sometimes it’s helpful to bring a friend into the studio and then I can see it through their eyes, and possibly see it in a different way. You get so invested in what you’ve created, but stepping away, turning it against the wall for a few days and then coming back to it can give it a freshness. I think the interval is important, and the ego is always there, but you can push it to the background a little. Toward the end of the painting, I think it gets very clear what’s successful and what’s not.

MH: Well sure, you get over the hump, but that hump generally doesn’t come until the very end.

FS: Yes, and I find that when I can’t do anything more to this painting, that’s when I know it’s done. It’s the best I can do in this moment, and that can be very satisfying.

MH: How would a masterpiece be recognized in the Buddhist tradition? Is it a painting in which the artist leaves no trace of herself?

FS: I think when there’s a universal quality to it, an authenticity; when there’s something that speaks to the individual but also moves beyond, that might be considered a masterful Buddhist painting.

MH: Maybe the concept of a masterpiece is altogether antiquated, Zen or no Zen. It requires a certain objectivity to state that a work of art possesses those rare qualities, and there are so few areas in our lives where objectivity still exists. Is it even relevant to talk about great art and artists?

FS: It’s hard to be objective. We all come with our constructed, preconceived views of the world, and it’s all so subjective. There’s a collective objectivity in how we look at a Rembrandt, but in terms of great artists and great art, that may be more for critics and art writers than it is for the artist. There are so many great artists who never came to fame and so many who never will, so I think that it’s more for the pantheon of art that we talk about greatness. It’s fun when they list The Top Ten Great Artists, but it’s kind of meaningless.

MH: Yeah, like when those annoying posts come across your Instagram feed, Ten Artists Whose Work You Need to Go See Right Now. I always wonder who was number 11? But the idea of a masterpiece, maybe that’s something you read about in art history books. It’s not a term I hear thrown around so much anymore.

FS: Yes, and there used to be more “isms”. Now it’s anything and everything, which makes it meaningless on some level.

MH: I’m sure you have paintings that you consider your most successful works. What do they possess or express that makes them so?

FS: It’s hard to put into words. The paintings that I get connected to are usually the ones that sell, and I don’t want to let them go. So why is that? I think it happens when things come together in a way that feels right and that is very satisfying, and somehow that comes through in the finished painting.

MH: Would you say that in your successful paintings, your ego wasn’t as involved?

FS: Yes, I think it’s when I was invested more in the process than the outcome. And it may have to do with how I come into the studio, like if I’m relaxed and focused and not thinking about other things.

MH: Could you elaborate on being more invested in the process than the outcome?

FS: I’m very process oriented. I love the actual doing of it, and I love that it’s so forgiving. I can put something down and make a mistake, then I can fix that mistake by covering it over or taking it off, so the process is energizing in its own way.

MH: It can also be very anxiety producing.

FS: Oh, absolutely! It’s totally anxiety producing trying to figure out what you’re doing, but that’s part of it. You have to allow for it or you’re not going to be able to make work.

MH: How do you balance your career as an artist, which depends to some extent on an indomitable ego, with your spiritual path, that seeks to diminish the ego?

FS: What always comes up for me is the issue of wanting. How much do I want, and is there an end to wanting more? It’s a fascinating question because in Buddhism it’s all about acceptance. It’s okay to want, but you should know why you want something, and when enough is enough. We have all these expectations, and we cause ourselves so much anxiety. Buddhism isn’t about denying yourself, it’s about learning to accept your life and all its ramifications.

MH: Would you say a few words about your current show at Kathryn Markel?

FS: The title of the show, Taking the Backward Step, is a quote from Dogen, the founder of Soto Zen Buddhism. It’s about turning inward to look at yourself and the world and experience the present moment without judgment or attachment. I thought it was a great description of how I move inward into the painting. My work evolves slowly and I’m trying to leave a little more in them than I usually do, rather than subtract them right away.

MH: What’s the best part about being an artist?

FS: Being able to go to my studio, to be by myself, and then have the opportunity to share it with people. I love the art community, which is so supportive and generous, and I love the process of struggling with a painting. It’s a very fortunate life that we live, and very satisfying, and I don’t take it for granted.