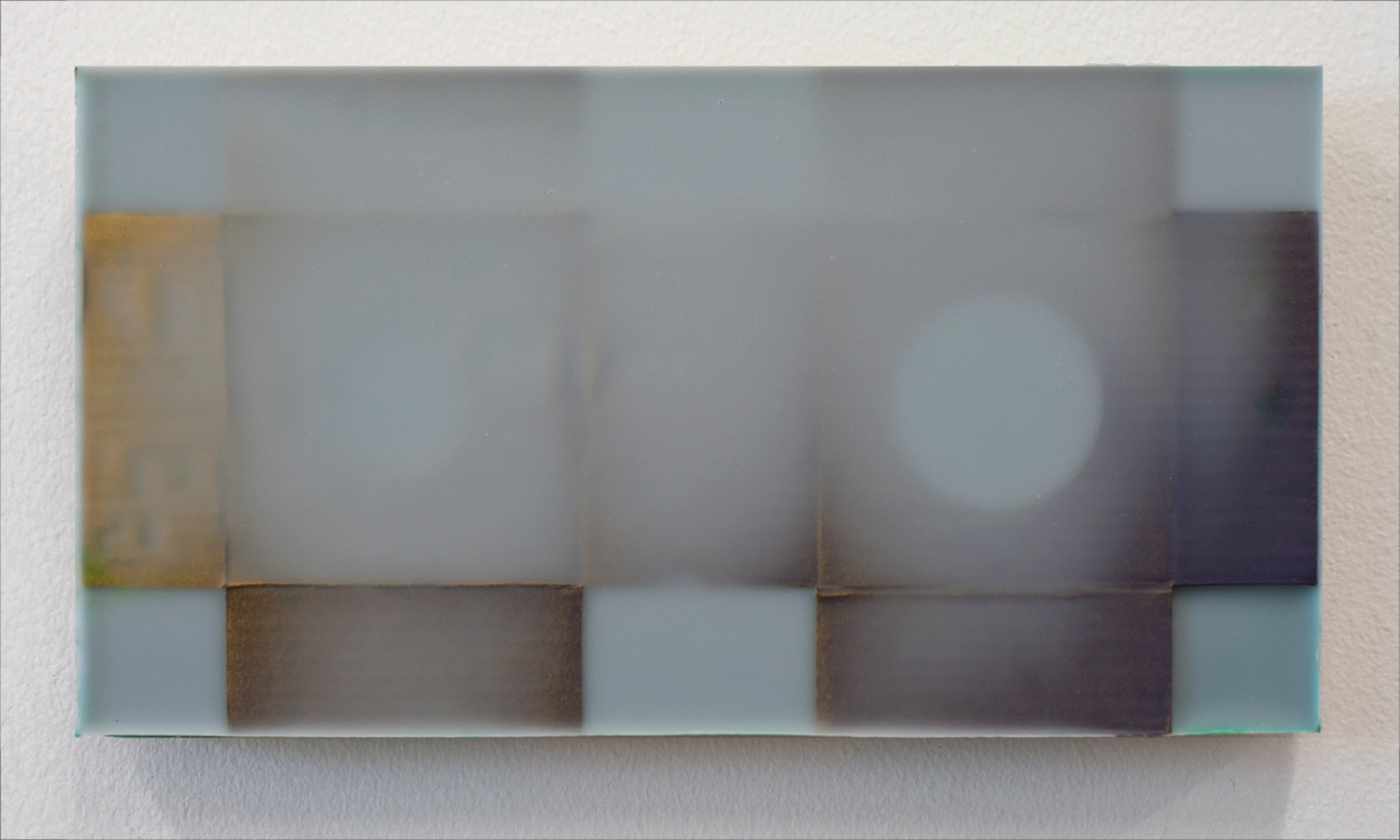

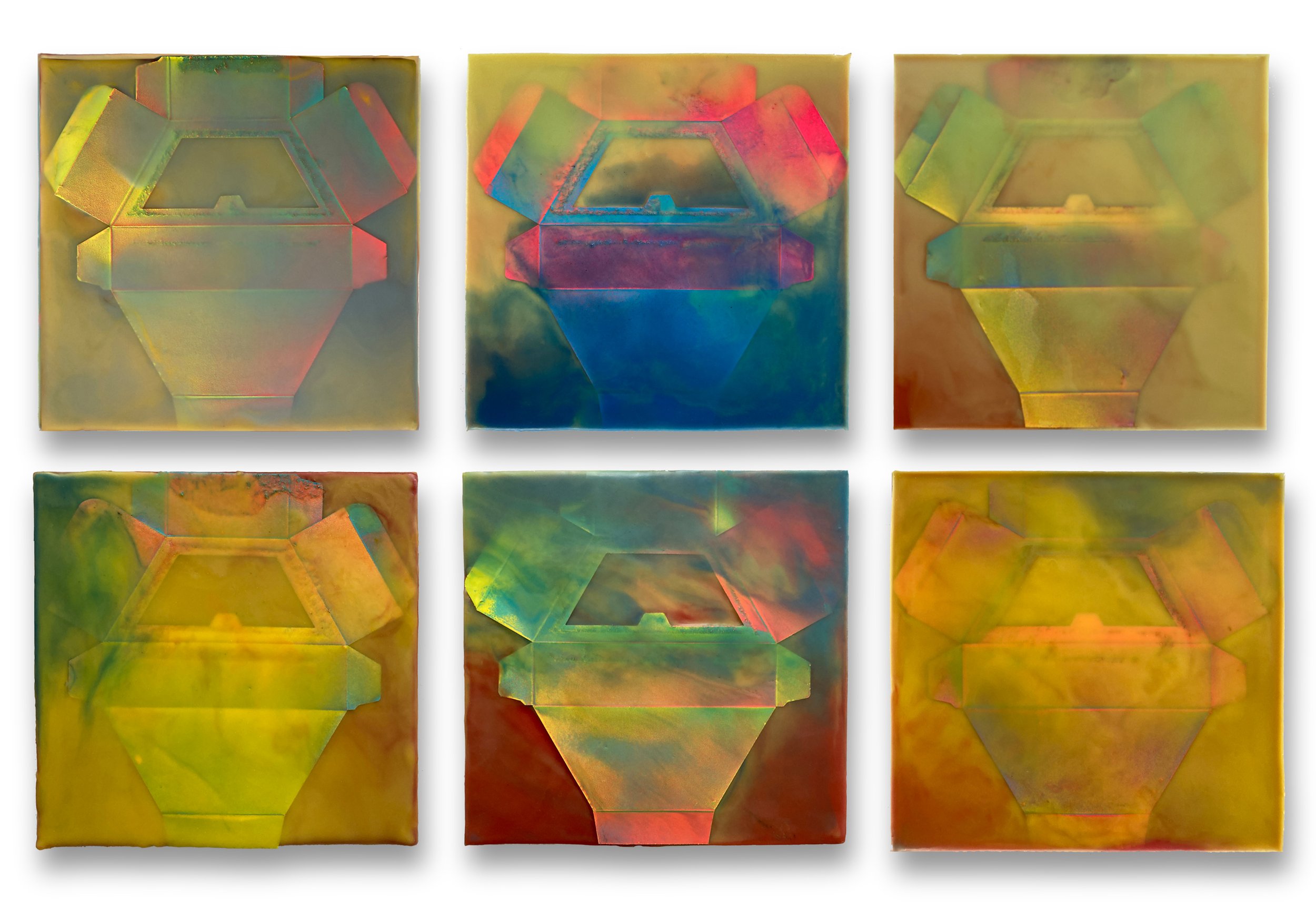

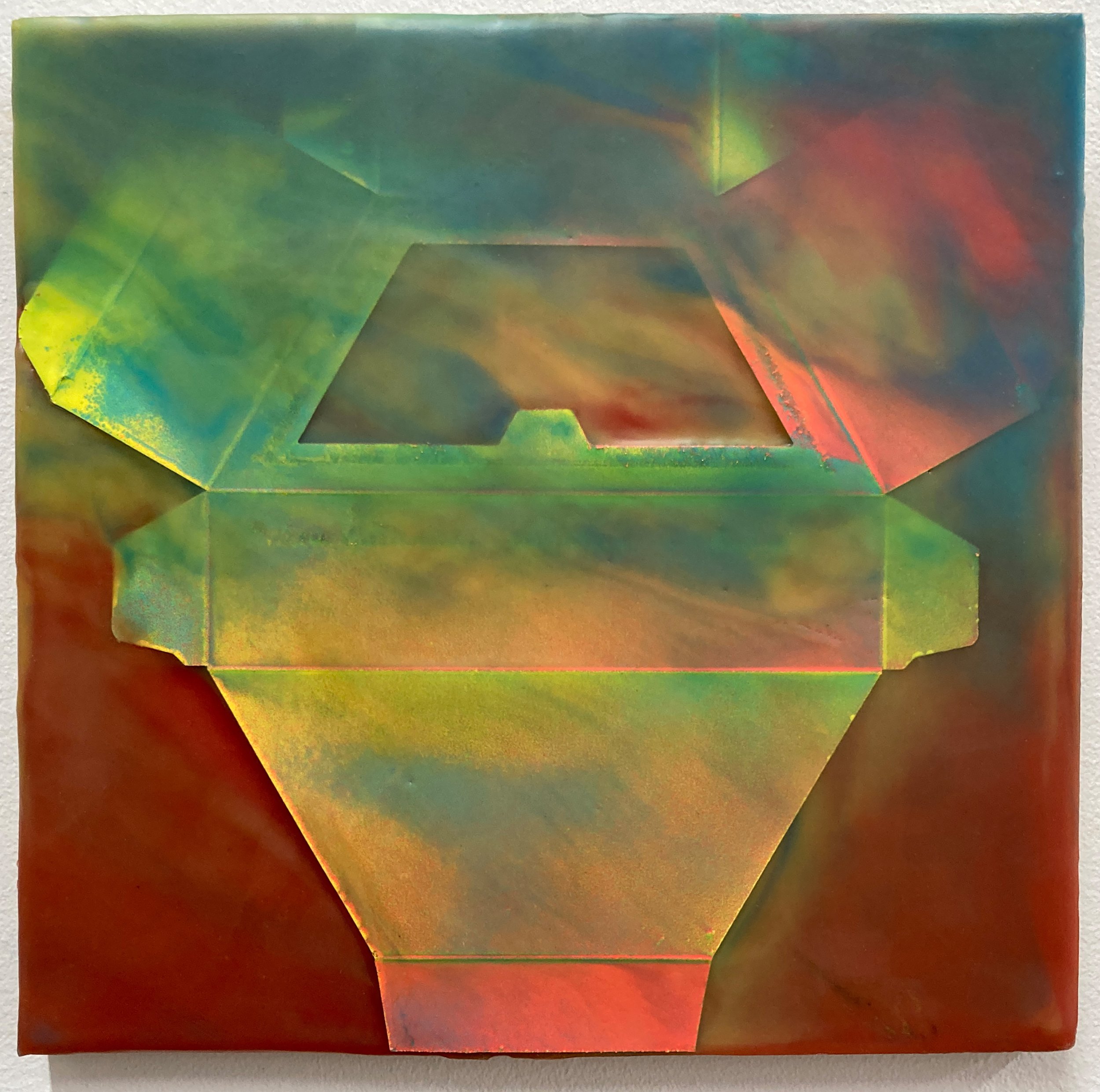

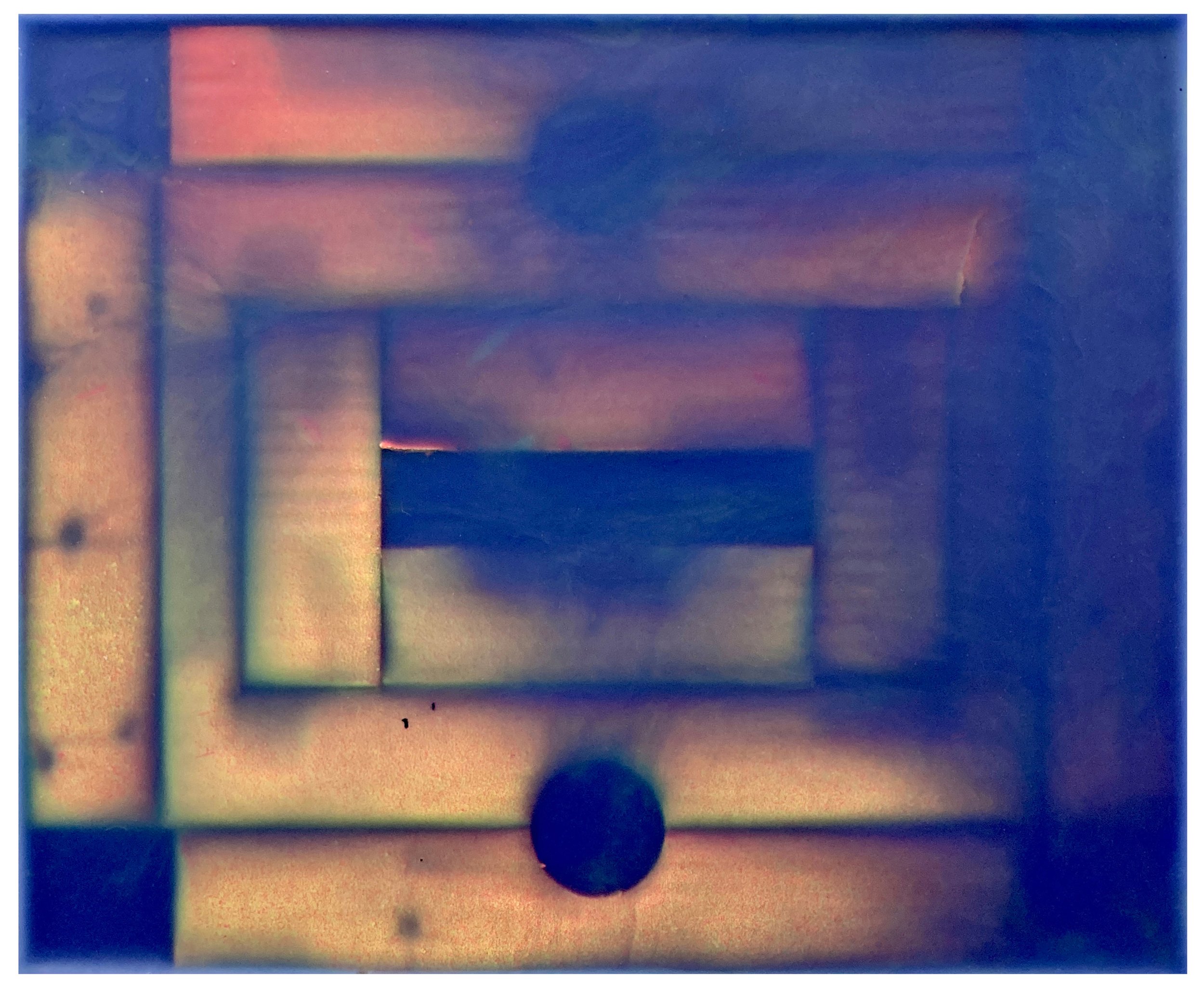

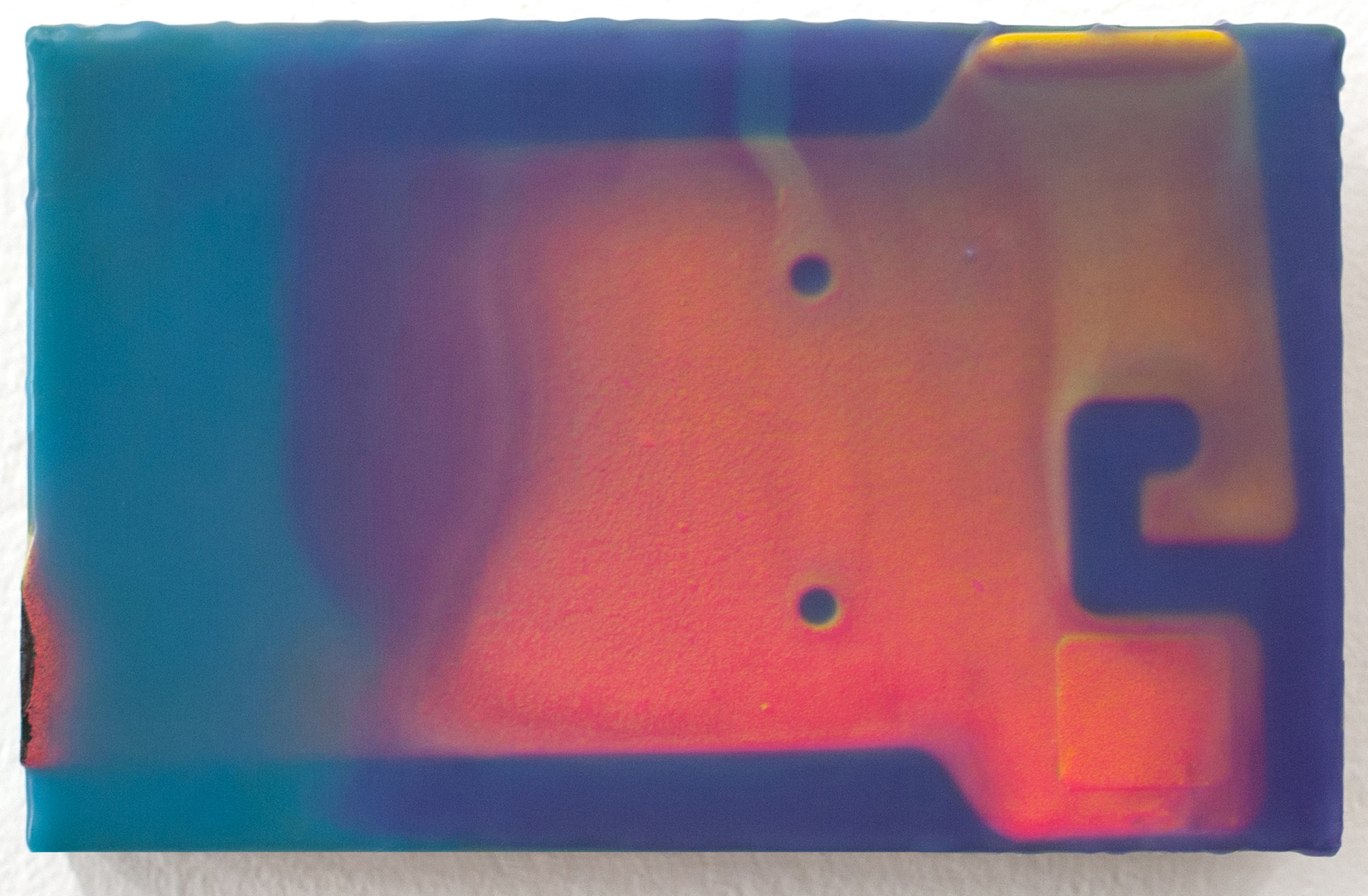

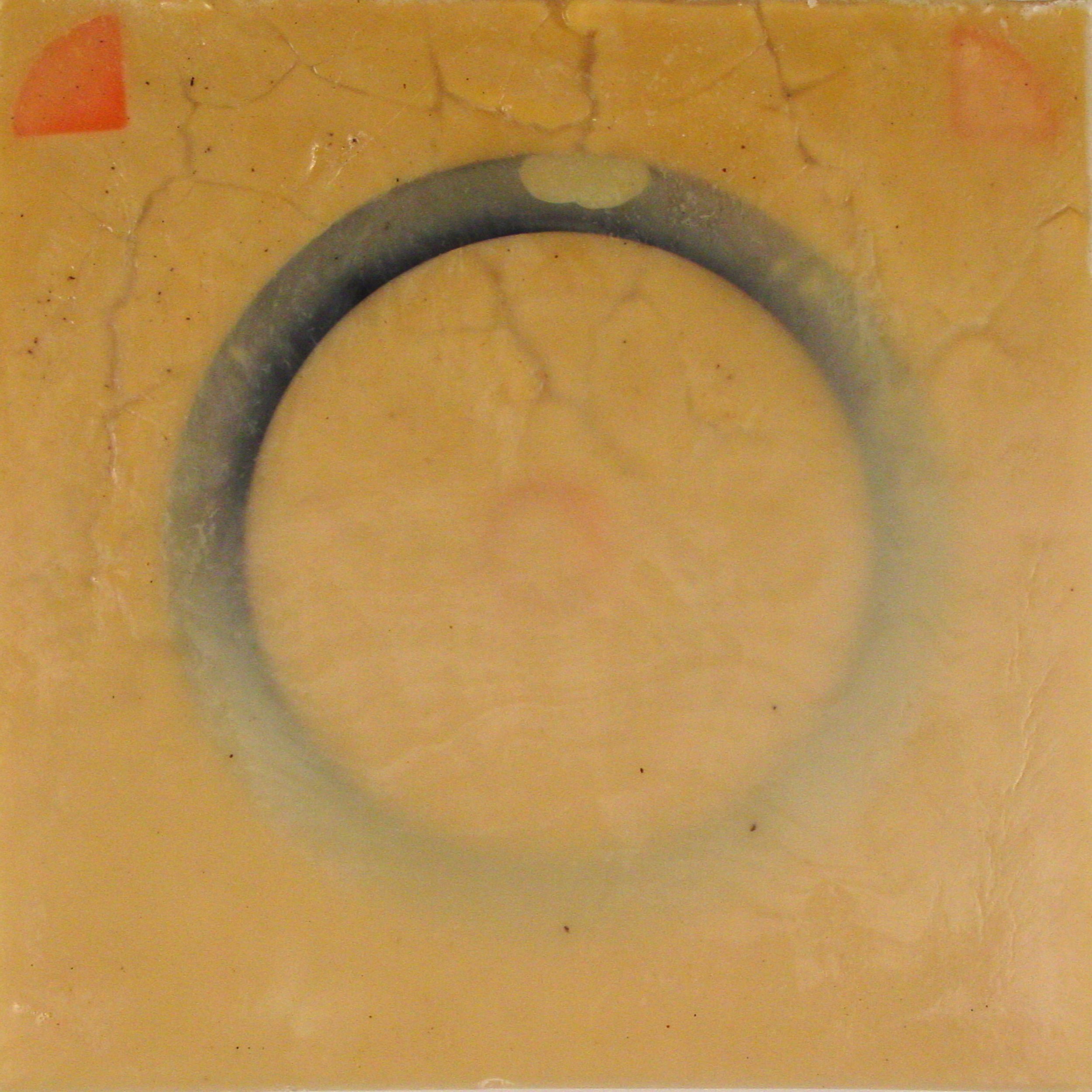

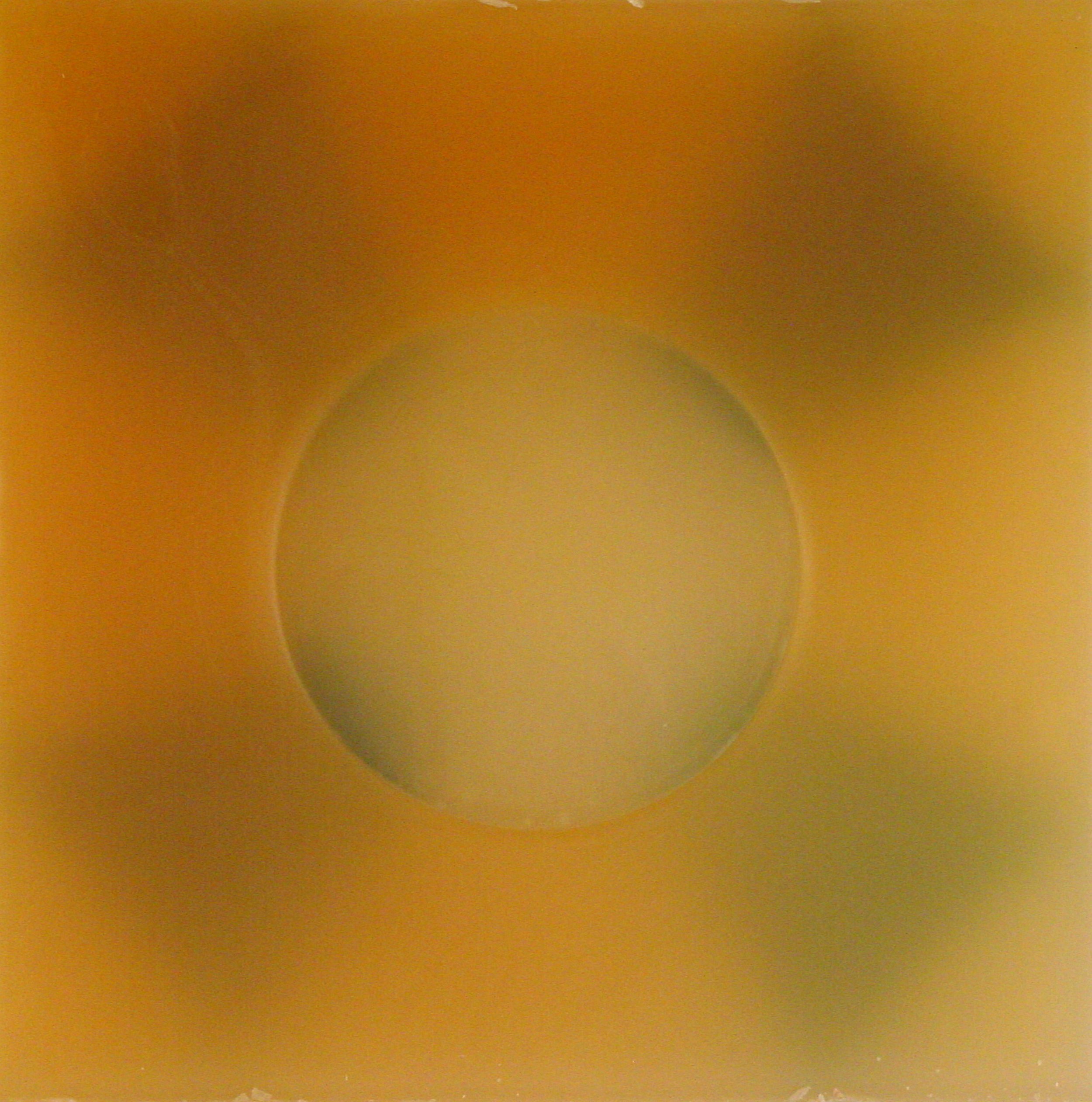

Part and Parcel, Joanne Ungar’s solo show at Front Room Gallery, consists of a series of encaustic works that appear as luminous, shapeshifting forms. On closer examination, the alien figures emerge as if through clouds to reveal themselves as the cardboard packaging that you throw in the recycling bin every week. Ungar began using cardboard when she worked in the cosmetics industry, deconstructing the packaging that contains lipstick, eyeshadow, and the elusive concept of beauty itself. This early series is a commentary on an industry whose success lies in undermining the self-esteem of the women who value its products. Later, she departed from feminist-based work to explore a more environmental approach, based in consumerism and the recycling of materials. Her work enshrines a product that has become ubiquitous in our materialist culture; indeed, cardboard is so central to our economy that it hardly needs explanation as a symbol of consumerism and waste. But Ungar’s use of cardboard is not purely conceptual; she’s also passionate about its properties as a raw material in her creative process. She waxes poetic about encaustic, explaining in detail how the tiny bubbles rise to the surface and pop as the wax solidifies. Her palette, once understated, has become saturated with color, elevating the cardboard to a thing of beauty and desire. Relieved from the function of protecting the object of value that’s being shipped, the cardboard is now that object, an irony not lost on the artist. Ungar embraces her medium with all its contradictions, and her work radiates with an inner light that transforms common materials into objects of uncommon beauty.

MH: You’ve been working with cardboard and encaustic for a long time. When did you start combining these two materials, and what about your medium engages you?

JU: I started working with wax about 25 years ago. I was searching for another translucent medium to employ in collage making, after having previously worked with resin, Elmer’s glue, acrylic medium, and anything else I could get my hands on. For a while I suspended bubble wrap in the wax, and eventually I started using found and fashioned objects, including cardboard. I find my process to be mesmerizing and endlessly engaging. When I’m working with wax, it goes through transformations from solid into molten and translucent, and then when it starts to cure it becomes opaque, then it becomes translucent again. The unknowingness and the lack of control is really at the heart of what I like about it.

MH: How did cardboard become your medium? Was it a moment of inspiration, or the gradual evolution of a cool idea?

JU: Initially it was economy and availability. I could cut cardboard into any shape that I wanted, and I liked the way that corrugation, which is made up of little tubes of air, reacted when it was submerged in wax. It gave me interesting and cool results.

MH: That’s interesting. The hot wax rushes into the little tubes, and then what?

JU: Well, it’s always different, but one of the first experiences that turned me on was submersing a piece of corrugated cardboard in wax. As the wax was coagulating, the air was squeezed out of the tubes and little air bubbles rose to the surface, popping up around the edges.

MH: What’s your background? How did you become an artist?

JU: I just enjoy making stuff, being involved with my hands, not overthinking it. I went to art school, so I have the education and training, but I’m not that theory-oriented, and I’m not that business-oriented. The way I was raised and where I come from, I was very rule-bound. I’ve always been a very good girl, and I’ve always followed the rules. But in my studio, it’s another story. I get to do exactly what I want to do, and that’s very important to me.

MH: Regarding your process, it looks like sometimes the cardboard is used without altering it, and other times you paint it. What’s your thinking behind that?

JU: Initially my work was more monochrome and subtle. Over the years I started using more color, and I’m at the point now where I’m using tons of pigment. The work is highly chromatose—a word that I made up—and painting the cardboard is one aspect of that. The paint creates an illusion of depth that I wouldn’t get otherwise. I like this sleight of hand, where people look at a piece and can’t figure out how I did it. I like it to be unknown; it gives me some privacy.

MH: Does your use of non-traditional materials bring a component to your work that you might not be able to achieve with traditional painting? I’m curious because they’re paintings in the sense that they’re two-dimensional, but a three-dimensional object is embedded in the painting. How do you think about this?

JU: Most of the art that I love and admire is painting, but I don’t consider myself to be a painter. In my heart I feel like these are assemblages or collages because I’m putting materials together. I say that I paint, but I don’t use brushes at all; I use encaustic pigments and I melt them into small containers of molten beeswax and encaustic medium. And the cardboard is spray-painted.

MH: Your compositions are intriguing, because the cardboard goes right up to the edge, with no border. I find it aesthetically pleasing, but it could also feel a bit claustrophobic. What consideration goes into your compositions?

JU: To create freely I have to give myself some boundaries. When I first started working with boxes, I gave myself the rule that the dimensions of the box would define the size of the piece. If you look at my earlier work, it was less claustrophobic—there was more space around the edges. But to your point about claustrophobia, to me that creates a visual tension between the space and the hard edge of the boundary. And I’m really into the negative spaces that are created.

MH: What about the “beauty” aspect of your work? Some of the boxes are from the packaging of cosmetics, and you used to work in that industry. Do you make any connections between your work and the commodification of beauty?

JU: Absolutely. That’s how it all started. Before working with boxes, I was using cosmetics packaging: false nails, eyeshadows, mascaras, lipsticks. I was doing it very consciously because I felt bad about working in that industry, specifically the way it commodifies women, homogenizes them, destroys the self-esteem of young women, and so forth. The reason I moved away from it was that the materials were very small, like 2 x 4 inches, so if I wanted to go bigger I had to use larger boxes.

MH: It’s interesting that your surfaces that have the appearance of flawless skin.

JU: That’s part of it, and I’ve spent maybe the last 15 years mastering that technique. It’s just with this current show that I decided to let go of that, because those pristine surfaces are not tantamount to my personal success anymore. I’m looking for more dynamic and interesting surfaces. In the past, if anything breached that surface, I’d abandon the piece.

MH: Your choice of material lends itself to many interpretations. For instance, you could be making a statement about the environment, consumerism, or any number of things. How do you think about your work now?

JU: At this point I feel like my work relates more to materialism and consumerism rather than the beauty business specifically. One of the many reasons I like working with the cardboard is for the recycling and sustainability factor. We create tons of refuse that isn’t reused, so my current work addresses that issue. But it’s not just about the waste, it’s also about the way that we’re manipulated by advertising agencies. So the conceptual aspect of my work has changed from feminism to a more environmental approach.

MH: Does the cardboard, which is very ordinary, bring with it an energy or allusion that’s in keeping with your values? You could have used candy wrappers, McDonald’s containers, book pages, or gold leaf, each of which would have communicated something different. What does cardboard communicate?

JU: That’s a great question. It has a personal appeal for me because I’m from the Midwest and was raised to be very modest. You don’t brag or toot your horn or draw attention to yourself in any way. As far as materials go, used cardboard is about as modest as you can get!

MH: Right. Cardboard has a lot of unfortunate associations. Like when you see unhoused people on the street, they often have shelters built of cardboard.

JU: Right. Seeing people living in those cardboard shelters make me so upset. But in general, I don’t associate cardboard specifically with being unhoused. I associate it with wastefulness and pollution and destroyed trees. I feel good about re-using it, giving it second life instead of sending it to a landfill.

MH: Cardboard has become ubiquitous in our lives, especially since Covid. We order almost everything online now, and it has to be shipped in a cardboard box. It’s interesting that your work enshrines the product that has become indispensable in our culture.

JU: Right! Every piece is made with a custom mold, and I make those molds out of used cardboard. So every cardboard box that comes through our house goes to my studio, and I cut it up to make these molds. There’s a part of me that would like to stop buying art supplies altogether and just use what’s in my studio.

MH: How do you feel about people misinterpreting your work? Like an annoying art blogger who assigns meaning that has nothing to do with your work. Is it humorous? Cloying? Unconscionable?

JU: That doesn’t happen to me. What does happen is that people say they see things in my work, like a landscape. And that’s fine with me, but in general, I don’t get accused of creating something that I didn’t intend to create. If there’s ever any negative feedback, I don’t hear it.

MH: Beyond the artist’s intention and the critics’ interpretations, do you think art has a higher purpose?

JU: Absolutely. Life without art would be intolerable. Art brings aesthetic pleasure to life, which is a basic aspect of living. I mean, life can be a slog! But I think art and music and writing can transport people to a place of beauty and transcendence. Visual art is a facet of that. The people who buy my work tell me how much they love having it on their wall. That’s so rewarding! That’s really all I need, knowing that other people get it.

MH: What about the artist’s concept or intention? Does it even matter what her work is about? I’m starting to think that what we create is irrelevant, and that it’s all about another energy that comes through the work. And that is what people are reacting to, not the lofty concept.

JU: I totally agree. When I get stuck and feel like what’s the point, eventually I come around to the understanding that my job is just to make stuff. You just make it, and let other people worry about the meaning. If instead I say, “Okay, today I’m going to go make work about recycling and waste,” it’s always a dead end for me. What I end up making is something very different, and it has nothing to do with where I started. I used to think it was a failure, but I realize now that all I have to do is start somewhere and be open to the process, to the universe. They don’t teach you that in art school!

MH: You could even say that the artist’s concept gets in the way or bogs it down. Kandinsky, one of the first non-representational painters, placed so much dense theory on his work that he may as well have stuck with landscapes. Your work is abstract, or at least an abstraction. Are you content to let it speak for itself, even if the concept gets lost in the shuffle?

JU: Yes. I’m very happy to let other people theorize about it if they want to, but I’m not that invested in what other people think about the work. Again, it’s the one part of my life where I get to do what I want. In other parts of my life, I can be judged and assessed on all kinds of things, but in the art studio there’s a freedom from all of that. I do what I want to do.

MH: What do you want people to receive from your work?

JU: The word that comes to mind is thoughtfulness. My current body of work is what I call tricky, meaning the viewer often can’t figure out how I’ve done what I‘ve done. For me, this is a gateway into the viewing process, as it starts someone thinking and looking more closely. I am always delighted to hear how folks receive it and respond to it. Ideally, they’ll think about how wasteful and how ugly our consumerist culture is.

MH: What’s the best part about being an artist?

JU: I get to do whatever I want. There’s a freedom of thought and action in my studio that I don’t have anywhere else. It’s a harsh world out there, both in nature and in society. I find making art and looking at art to be a refuge into a realm of beauty and thoughtfulness, where I prefer to be.

www.joanneungar.com

Ungar’s solo show Part and Parcel is at Front Room Gallery in Hudson, NY through November 26.