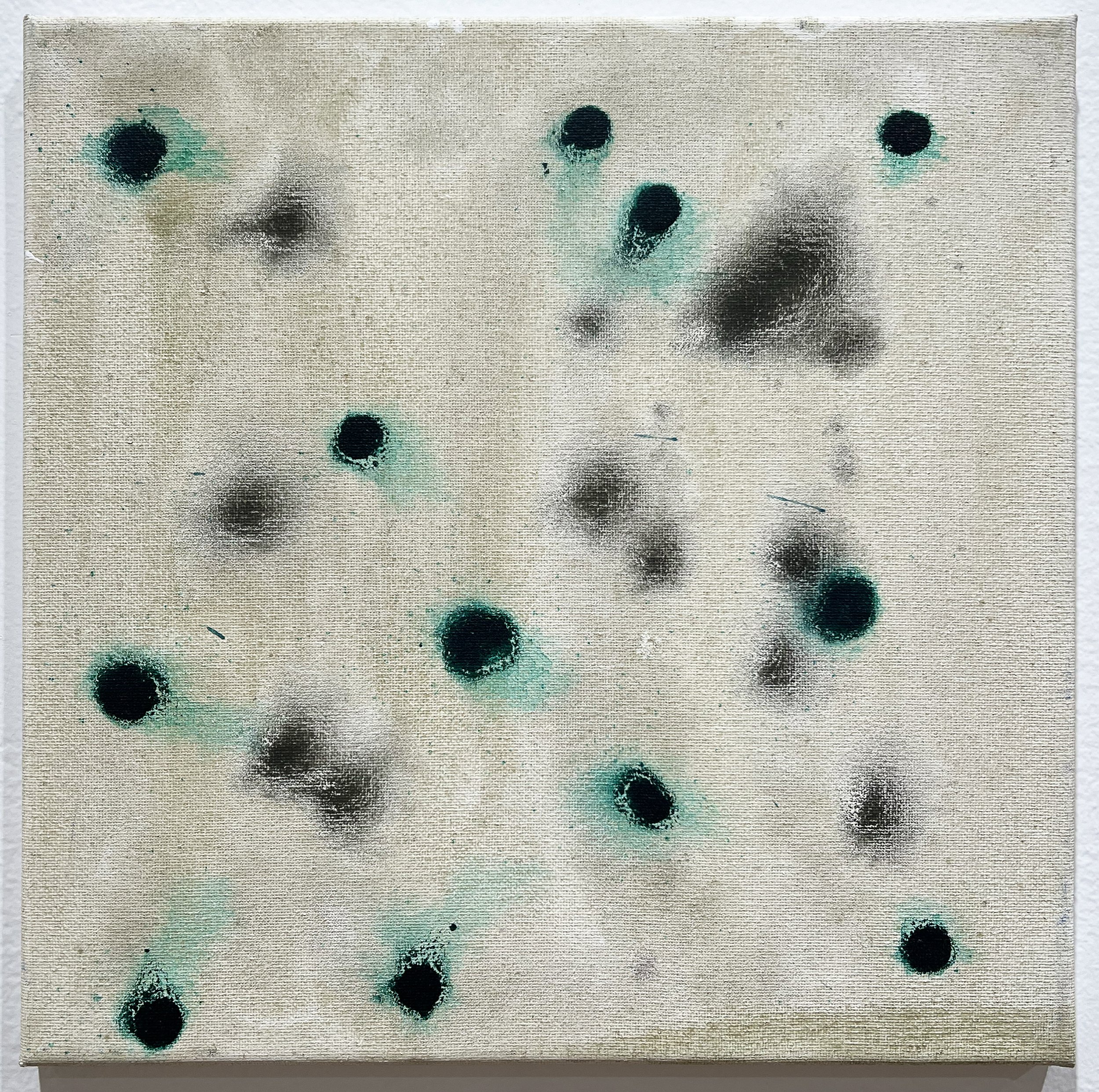

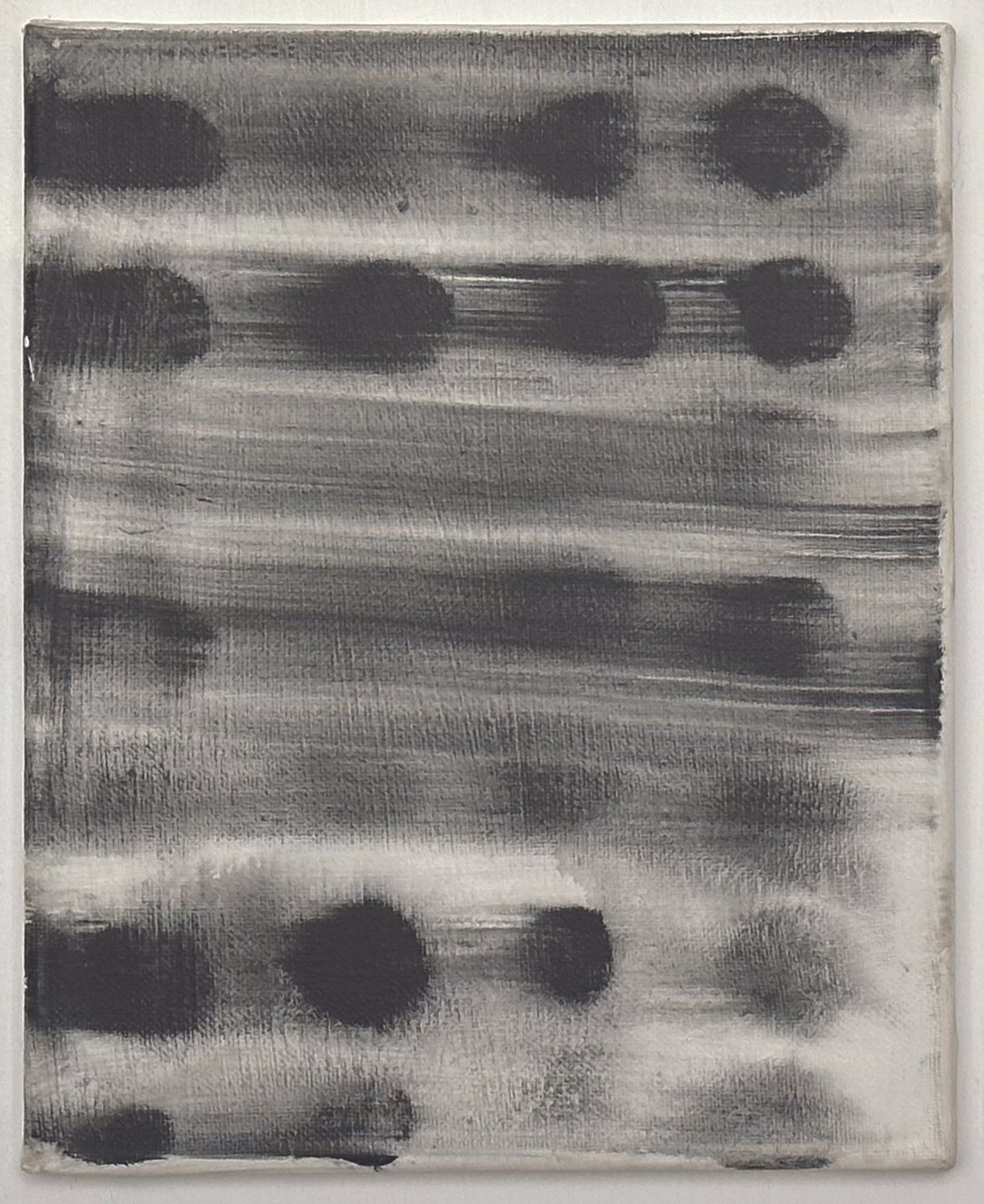

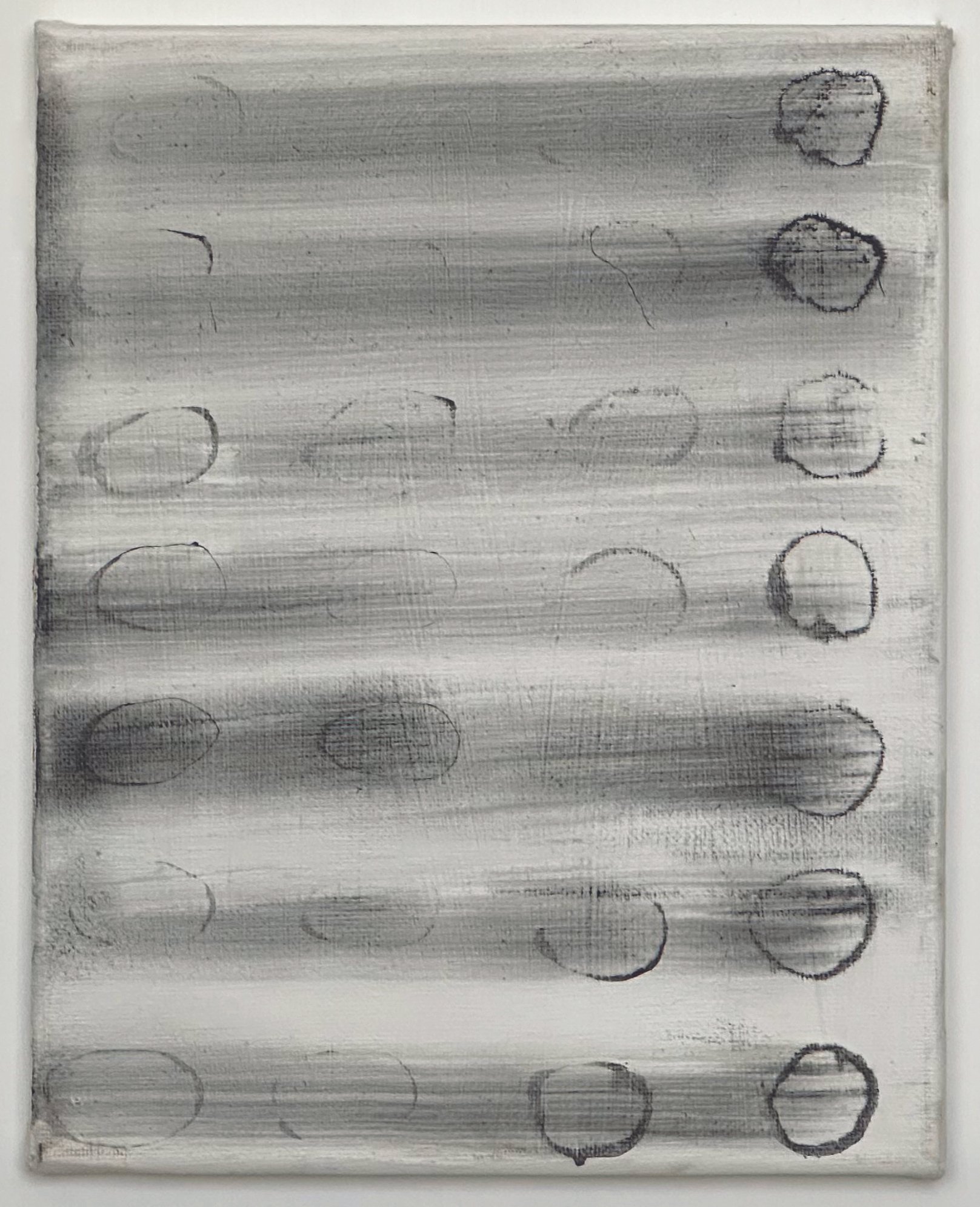

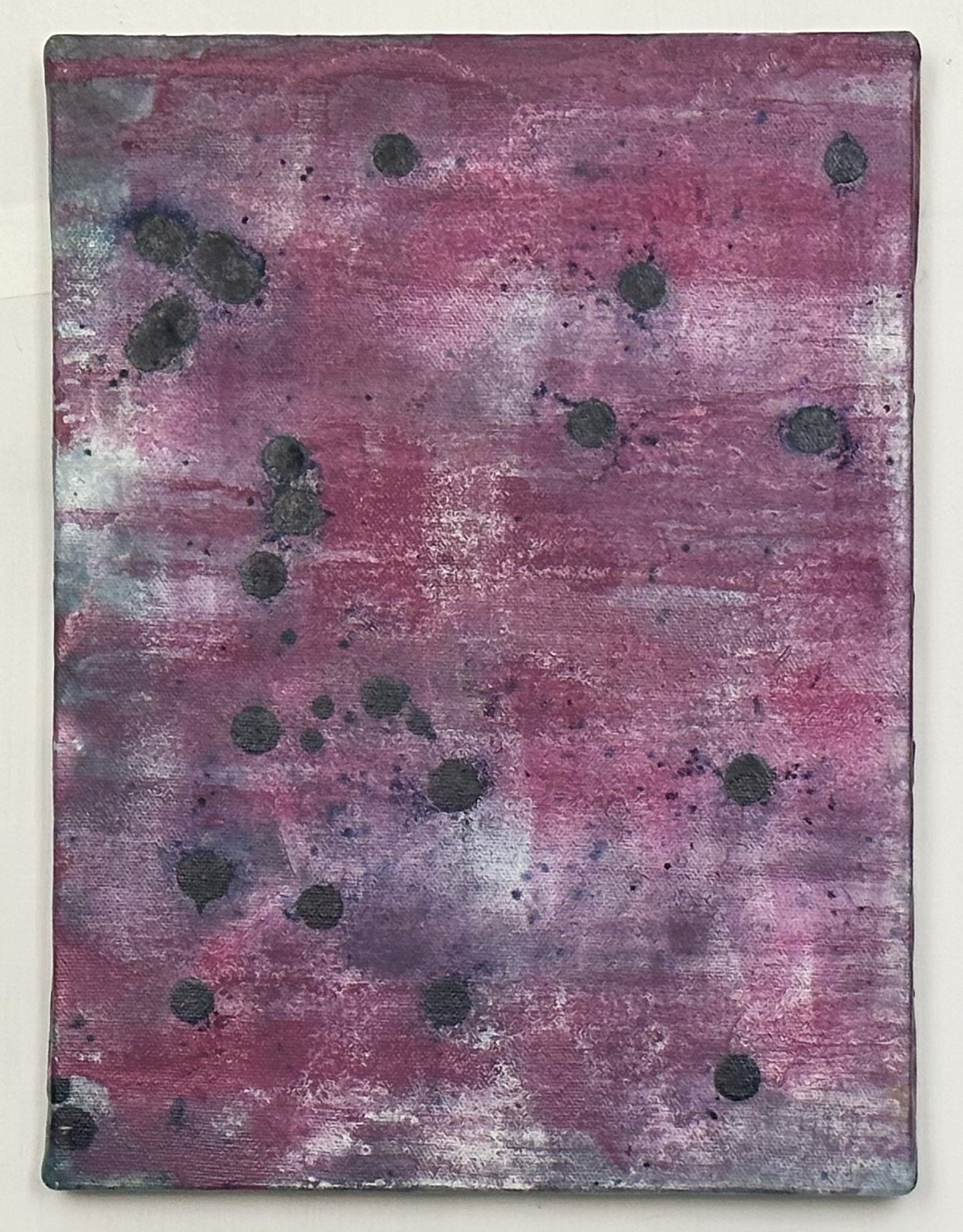

In her solo show Attempt to Form, Kate Horsfield exhibits her recent body of paintings and ceramics in which she explores the relationship between form, emptiness, and abstraction. Horsfield pushes the parameters of traditional painting by allowing her compositions to fall apart, as if succumbing to the laws of entropy. Through a process of reduction and elimination, she removes all allusions to the external world, relinquishing the shapes and shadows that tether us to representation. Her work originates in an approach that is minimally invasive, where the artist defers to the paint, medium, and gravity to determine the outcome. Horsfield begins each painting by dripping paint onto the canvas, spraying it with turpentine, then allowing the paint to do what paint does. This relinquishing of control is at the heart of Horsfield’s practice; she becomes an observer of the active paint, engaged but not engaging with its movement as it spreads and settles. The resulting forms are nebulous stains in a field of emptiness, a collaboration between artist and medium in which there is equal influence. Horsfield’s paintings read as ephemeral exhalations, suggesting that after a painting has been emptied of pictorial content, the breath of the artist is all that remains. The finished painting may be regarded as a dance between form and emptiness, doing and not-doing. Her ceramic sculptures are similarly spare in contour and color, their looping lines reminiscent of Chinese calligraphy. The authentic, unpolished surfaces of her paintings are repeated in her ceramics; indeed, the two are of a piece, informing each other and confronting the solidity of their respective forms. Horsfield’s two- and three-dimensional works challenge the space they occupy and read as visual oases in a continuum of emptiness. In her departure from traditional iconography, Kate Horsfield encounters the metaphysical realm, where form, emptiness, and abstraction are in an eternal process of unfolding.

MH: You were a graduate of the Art Institute of Chicago, where you and Lyn Blumenthal created the Video Data Bank, your project from 1976 - 2006. How did that project inform your work as an artist?

KH: Our video project started in 1974 with an interview with Marcia Tucker, the founder of the New Museum. As young artists, we were interested in how older artists decided what they wanted to do, how they worked with their materials, faced accidents in their work, and so on. This was the height of the feminist movement, and we were particularly interested in hearing women talk about the motivations behind their work. Listening to all these artists talk intimately about their practices and values was very influential, not so much in my work, but more of a sense of dedication, of adopting good artistic values and practices, rather than wanting to get involved in making money.

MH: You left the Art Institute in 2006 and taught drawing and painting for a year in Austin, Texas, then returned to New York in 2008. At what point along the way did you dive back into your studio work?

KH: I had a studio in Austin, so I was painting while I was teaching there. But I started painting seriously when I came back to New York and sublet a studio at the Elizabeth Foundation in 2010. Then I had a variety of different workspaces, including PS122 in the East Village for a few years, then at Brooklyn Fireproof in Bushwick.

MH: What you had to say as a 20- or 30-something artist undoubtedly changed over the intervening decades. Was it challenging to rediscover your voice as an artist?

KH: It was extremely difficult at first. Consistency and time make a huge difference as an artist, and I’d been working full-time for many years, which impacted my development. So when I first walked into the studio in 2010, it was a strange experience for me. I really had to start from scratch.

MH: You said that you were searching for a painting surface that was pleasing to you, so you started applying paint to the canvas, then removing it. What did you discover through this? And was the process also satisfying?

KH: Yes, I was trying to flesh out what I wanted in the way of surface. I knew what I didn’t want but didn’t know yet what I wanted. There’s a phenomenology of paint, of putting paint on a surface and then allowing it to move around in a random way, without my having control over it. There's something about both manipulating and not being able to manipulate the color moving across the surface that I find very interesting. I also found that to be extremely interesting in ceramics, and it wasn’t a big leap for me to take the painting process from a flat surface to a three-dimensional surface.

MH: At some point the painting started to “fall apart”, in your words. How so?

KH: My aesthetic started to change; even abstract shapes became too literal for me. How do you talk about things falling apart without going into any kind of representational iconography? So I came up with a new way of working on the surface using a spray bottle, dripping paint, and letting the color go wherever it does. I manipulated it slightly, but mostly it was just gravity. And although I wasn’t thinking about it at the time, this reflected what was happening in our country. Some of the things that I and my generation fought for in our lifetime were falling apart, the things that were solid were no longer solid, and I wanted to find a way to talk about this in my paintings.

MH: Your paintings are minimal, both in palette and form. It seems that in your search for authentic expression, yours is a reductive process: how much can I take away and still have it hold together as a painting? Is that a fair assessment?

KH: Yes, it’s very reductive, but the paintings can also be quite complex. There are a lot of things happening on the surface, but temperamentally I like the ones that are almost empty. The emptiness of it, in addition to the random flow of the paint, were the things that were most interesting to me. What is the least thing that I could do to make a painting look like a painting? That's an old idea in art.

MH: So you were feeling disconnected from the process of painting, and it was making you feel anxious. Then you had the opportunity to play around a little with ceramics, and everything changed. How did working with clay open things up for you?

KH: Ceramics had never been very interesting to me, but a friend encouraged me to try it, and I took to it instantly. It was like an explosion went off in my head, and I realized there was something incredibly liberating and primal about working with clay. I found that I didn’t have the anxiety working with ceramics that I had with painting. Painting was so loaded for me that it was very hard to do, but with ceramics I was able to let go of any expectations and make something and it was okay.

MH: Once you started working in ceramics, did your paintings start to make more sense? Is there a connection between the two mediums that’s integral to your work?

KH: When I started in ceramics, I didn't make a connection to what I had been doing in my paintings at all. It was just a different thing. But when I pulled out some of my paintings and looked at them, I could see a line of progression between the two practices. And I was thrilled by that, because I saw that I had been pursuing this vision all along.

MH: It sounds like ceramics made you more comfortable with painting, and painting made you more comfortable with ceramics.

KH: Exactly. They’re tied together somehow. Artists need to see connections in their work; it needs to somehow make sense. The similarity between the two has to do with the process of applying and taking off color in both ceramics and painting. This creates the kind of surface that I like, no matter what I’m doing. I like it to look aged, less refined, more authentic.

MH: Do you find that in your work with clay, you have a similar desire to reduce the formal elements? I suppose you have to work with the fact that it exists in space, and there are practical concerns. Like, it has to not fall over.

KH: Right. It has its own rules and you have to follow them. The pieces that I’m working on now have loose, loopy, open spaces, and I see them as individual strokes in space, like calligraphy in a way. That’s a very fragile ceramic space, but it might be a strong painting space.

MH: What is it about representational art that’s problematic for you? Does it create tension? Or is it simply that there are enough artists doing it that you don’t feel the need?

KH: Interestingly enough, the way I decided to become an artist in the first place was that I was really good at rendering. I was good at the things that people think an artist should be able to do! So my progression as an artist has been to move away from that. I don’t have anything against representation, but I don’t particularly need to do it myself.

MH: In your process of reducing a painting to its absolute minimal color and form, you lose a lot: imagery, a full palette, and arguably, self-expression. What do you gain? Why are you drawn to work minimally?

KH: I don’t lose self-expression—that’s actually a gain. There’s something about emptiness that attracts me. It’s not just on a canvas or in ceramics, it’s also in the physical world. I grew up in Amarillo, Texas and I love empty space; I feel comfortable in that landscape. The minimalists proposed that if you give less, the audience will fill in the blanks, and I find that to be true. Agnes Martin talked about the fact that some people didn’t like her paintings because it required them to have an internal response. A lot of people don’t like that feeling, but I happen to be very attracted to that.

MH: So much of your studio practice is about reducing and reducing, getting your painting down to the barest expression that it can handle and still be called a painting, and then someone comes into the gallery, sees your painting, and says, “Oh, what a beautiful seascape!” Is that like your worst nightmare?

KH: Not at all! I find that to be incredibly interesting. As artists we have to accept that we have our ideas about what we’re making, but once you put it out into the world, you’re going to get a multitude of responses. I might not agree with someone’s assessment, but I think we have to be respectful of others’ reactions.

MH: Seascapes aside, what would be the ideal reaction to your work?

KH: I would hope that someone would try to see if there’s something in the painting or sculpture that would be meaningful for them. Making the work is a phenomenological experience for me, like the sensation of putting red and phthalo green on a surface and observing how they intermingle. So I’ve collapsed narrative, content, and context down to a few dots that are floating around on a surface. That’s just my way of working. It doesn’t require anything intellectual, it’s more of a sensation than an intellectual understanding.

MH: You talk a lot about relinquishing control and letting the paint do what paint does. It’s almost as if you’re trying to disappear from the equation. Does this resonate with you?

KH: Yes, in a way. I think if you’re willing to give up control, you’re going to get unexpected results, some that you like and some that you don’t. There’s some manipulation on my part, in terms of getting the paint to flow in a different direction, but for the most part I’m allowing a kind of randomness to take over.

MH: Is the culmination of your reductive process an elimination of yourself? Not in a nihilistic sense, but in the Buddhist tradition of no-self?

KH: Yes, it’s definitely there. You can make a correlation between minimalism and empty space. But anyone who sees my show has to come up with their own conclusion about what it means without me telling them.

MH: Would you say that your work points toward emptiness? The Buddhist term is shunyata, which translates as emptiness of ego and attachment. Or might it be an emptying of your creative energy into your medium, transferring it from yourself to the painting?

KH: Both are true, but I’ll take the second interpretation. Painting was always a struggle between seeing myself and not seeing myself. There are ways of seeing yourself in your work that are critical to any creative endeavor. But it’s okay for me not to be present in my own work; the idea of emptiness and draining out the ego is very attractive to me, even in painting.

MH: As artists I think we express ourselves through our medium, and effectively empty ourselves from whatever urge is compelling us. Then we show the work in a gallery or whatever, and the viewer is filled up from looking at our piece. It’s a transfusion of sorts, hopefully meaningful for the viewer. What do you think of the idea of art as a transfusion of creative energy?

KH: I hope that’s true. Beyond the goal of just making something, the idea of someone else coming in and getting something out of what you’ve done, particularly if they get what you want them to get – that sounds like the goal.

MH: Do you think that abstract painting has a better chance of that transfusion that we’re talking about? Because with a narrative painting, the story is another layer that you have to get through, whereas with your work, there’s no perceivable narrative, so is there a better chance of that transfusion happening?

KH: It really depends on who’s looking at the work, and what their experience with art is. The people who have more experience looking at art and are more tolerant of the radicalism of abstraction are going to feel it more fully. I don’t think people without a background in art can walk into a gallery and immediately fall for abstract or minimal work. The appreciation of abstraction is something that people acquire over time.

MH: What would you most like your work to transfer to your audience?

KH: I hope people look at the work and get some sense of pleasure and enjoyment from it. I think the ceramics will be easier for people in a lot of ways, maybe because it has more of a material reality.

MH: Do ceramics require less of the viewer?

KH: That’s an interesting question. I don’t want to re-ghettoize ceramics – it’s inhabited a specific space all these years and finally it’s stepping up the ladder of fine arts. Which means there are more ceramicists, more creative experiments going on that would match any other form of creativity. I think it’s building an audience right now.

MH: What’s the best part about being an artist?

KH: The practice of being an artist is a wonderful space to live in. You have a series of goals that go on for your entire life, and you have a community of artists who support each other’s practices. I look at this art world and I’m completely grateful that I’ve always been a part of it. No matter what role I played in it, there was always tremendous excitement to see other people succeed or make breakthroughs. I’m overwhelmed by what a great decision it was to be an artist – it’s just a wonderful life.

Kate Horsfield and Lyn Blumenthal directed the Video Data Bank at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago from 1976 to 2006. “Attempt to Form” is showing at the College of Staten Island Art Gallery, curated by Cynthia Chris and Siona Wilson. The show runs through October 19.