The first time I met Mandy Cano Villalobos, she was eight months pregnant with her third child, on her way to a month-long artist residency in Wassaic, New York. This tells you everything you need to know about the artist, whose uncompromising work defies convention and categorization. Working in a variety of genres, MCV uses nontraditional materials to register the mundane activities of her life. Stitching discarded clothing, painting transcendent mandalas with pig blood, dripping her own breast milk onto the floor of an abandoned silo, pushing a gurney laden with detritus around the city – these gestures point to the impermanence of objects and the vanity of accumulation. The theme of desire is present throughout her work, expressed in her ritual-based work as well as performance. I’m a fan of her Penance series, in which she burns countless holes in paper so that I don’t have to. MCV lives in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and we talked on Zoom.

MH: You grew up with a single mom in the army. How did you find your way into art? Was it fortuitous, or was it a choice?

MCV: My mother tells everyone that I came out of the womb drawing. My grandmother was inclined to make things, so I may have gotten some of it from her. When I was ten I started collecting antiques. I’d go around to yard sales and buy unusual stuff. But even though I had this pull toward art, I thought that becoming an artist would be a bad life decision. I thought about becoming an English major instead, thinking that I’d make more money. But my mom convinced me that it was a bad idea, and that I didn’t have the patience for anything but art. She was right.

MH: Do you want your kids to grow up to be artists? Is there a part of you that worries that they will?

MCV: I don’t want my kids to be artists! There are too many artists in the world already. I want them to be engineers, accountants, and executives so they can buy art and support artists, including me.

MH: Can you describe your performance piece “Motherload”?

MCV: It’s an ongoing project. A gurney is covered with the detritus of motherhood, and I literally push it around the city. Domesticity is this private thing, so I wanted to take the idea of being a mom and lug it around in these historically industrial, male-dominant places. In another version, I stuff a huge backpack with all the things of motherhood, and I trek around town with it on my back.

MH: You often use unusual materials in your work. I’m thinking of the pig blood, burnt paper, breast milk. Is there anything you’d like to say about your choice of materials? Do you find traditional materials such as paint to be limiting?

MCV: Oh, totally. I love the tradition of painting, and a lot of what I do has stemmed from a classical education. But at some point, I got irritated with the narrative of painting. The idea pushed in art school was that painting should be big, bold, and loose, and if I painted like that, I’d be good to go. It really turned me off from painting. My work was more body-oriented, which at that time was looked down upon. I’m also drawn to craft that incorporates materials that I collect, like bodily relics. I have a collection of fingernails from the women in my family that I’ll use in a piece. There’s something precious about these materials.

MH: How do you deal with boredom in the studio? When the inspiration isn’t there, do you take a break, or do you slog through?

MCV: I’m never bored. My studio is my quiet time. If I’m having issues with a particular piece, I always have twenty other things I can work on. Inspiration is overrated; you just do the work, and every now and then a lightbulb goes off and you do something amazing. But most of the time you just go to the studio and work, whether you’re inspired or not. Plus, my life is insane! I have three kids and a dog and piles of laundry – so no, I don’t get bored.

MH: When I spend time looking at your work, the word “devotion” comes up. Is that a correct read, and if so, what are you devoted to?

MCV: I definitely have a deep faith. I see everything that I do as having eternal ramifications. I feel that I have a very limited time on the earth, and my vocation is art making, so it’s my job to fulfill that purpose. If I didn’t have that larger belief system, there wouldn’t be any point.

MH: A lot of your work is repetitious in its process. On closer examination, I see it as an act of “intentional accumulation”. Whether you’re burning holes in paper, tying endless knots in red string, or gathering “stuff” for your altars, there’s an accumulation of actions and marks. What are your thoughts on this? Is there an underlying need to accumulate? And to what end?

MCV: Omg, yes. I think of every finished piece as a relic of my process. How can I accumulate my moments, and express them visually? My two-dimensional work explores how process and image relate to one another. My installations are an accumulation of stuff, this American problem where we try to create a sense of permanence and meaning through the acquisition of physical objects. When I was a kid we moved almost every year, so I collected old books and antiques because they offered me a sense of home and continuity. My installations speak to this contrasting aspect of accumulation, that it’s both beautiful and false.

MH: Is the work ironic, then?

MCV: It’s not ironic. It’s more about the desire for something that we’re not able to get. A fundamental aspect of being human is this idea that there’s something missing that we desperately want, but we’re never going to be able to get it.

MH: There is the Buddhist concept of “transfer of merit”, whereby the practitioner chooses to dedicate the merit that she’s accumulated through her meditation practice for the benefit of others. Your work has this quality for me, not in a religious sense, but there’s the feeling that you’re doing some good in the world by your considered, repetitive actions. Does this ring true?

MCV: To some extent. I can only control so much. I’m not going to save the world, but maybe there’s some good that I can offer in the limited time that I’m on the earth. Like, how does my studio work translate into my relationships? And I feel like I’m constantly asking, what’s the point? By creating objects that will live on after me, I feel that I’m investing in something greater than myself.

MH: Do you think that artists accumulate and disseminate good will in the world by doing their work? Taking the focus off from the “product”, do we generate basic goodness simply by spending so much time immersed in the creative act?

MCV: Part of me wants to respond with a resounding yes, but another part of me is way too practical to buy into that. I think that creativity is an essential human act, and there’s something about the process of creating that is fundamentally “good”. I love that part of being an artist. But the other part of me that was raised by the army mom is too practical to believe that artists can make such a difference in the world.

MH: What is the optimal response to your work? If you could control the reaction, how would you want people to respond to it? I’m thinking of your performances, which are so beautifully understated. What is it that you want to communicate?

MCV: I want people to engage with that piece that’s missing – that thing that we all want but can’t have. There are a lot of people who don’t even realize that the desire exists, and I want to connect with those people. I want to create the desire for something that’s beautiful and good. And I know that sounds very romantic, but whatever.

MH: What’s something about your work that’s not readily apparent?

MCV: That accumulation thing that you picked up on is important. I also think a lot about death and impermanence. The fundamental human desire for permanence and home is an important aspect of my work, probably because there was so much change early on in my life.

MH: What’s something about you that comes through in your work, that most people wouldn’t notice?

MCV: This idea that the artist is so important feels false. In a certain way, I think the artist should disappear in the work. I would much prefer that the work stand on its own. I find the art more interesting than the artist.

www.mandycano.com

Image List

1. Motherload (Gurney), 2021, performance, Chattanooga, TN

2. Motherload (Backpack), 2021, performance, Grand Rapids, MI

3. Throne of the Dog-Faced Girl, 2020, found object sculpture

4. It’s a Man’s World. Until it Isn't, (for Sheherezaad), 2021, found object installation

5. Corpus Snow, 2018, wine-stained cloth, snow, and dirt

6. Holy Ground, 2018, stained clothing, string, and dirt from Chimayo, NM

7. Things to Make and Do, 2022, hand scorched book cover, 9 x 7 in.

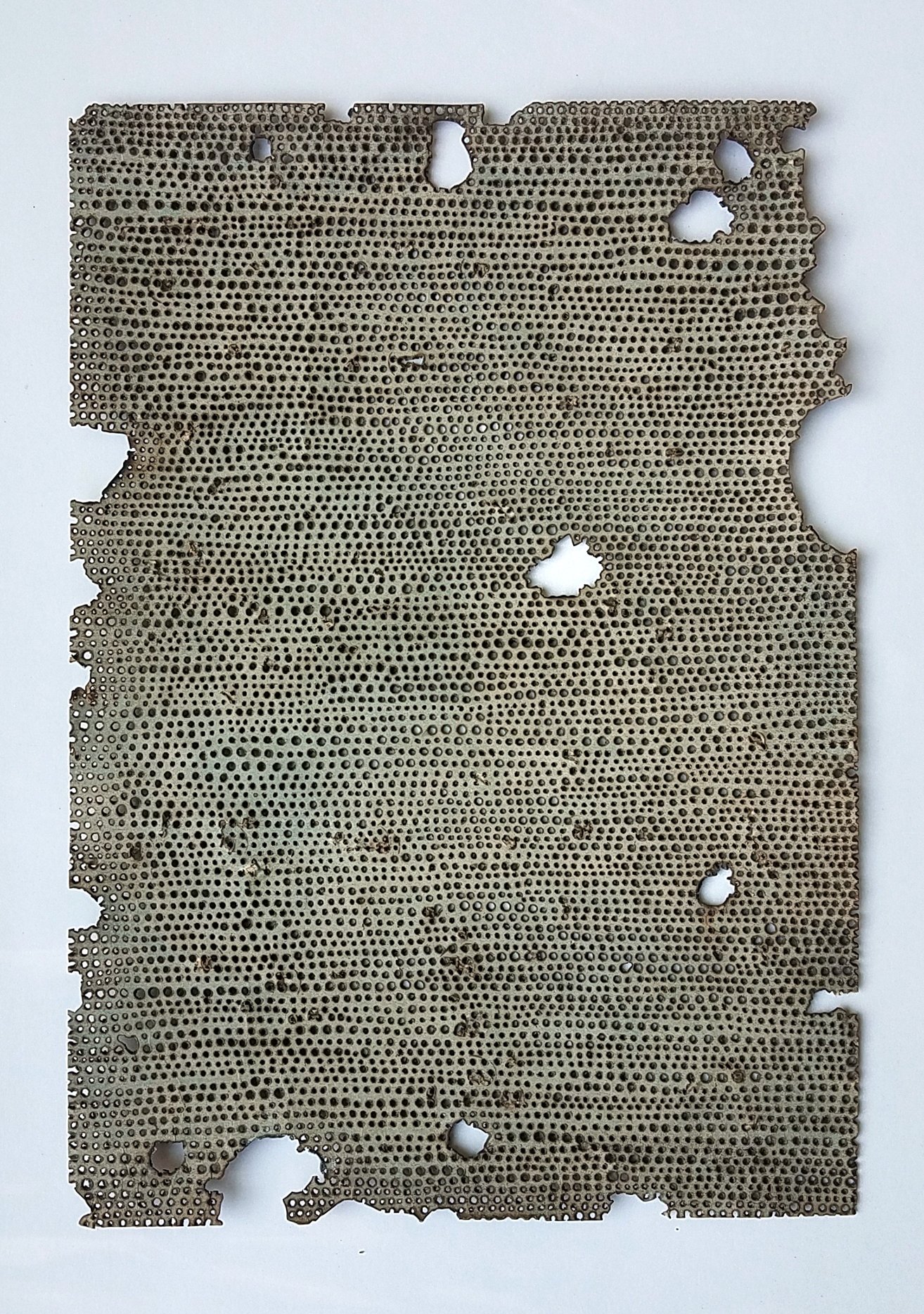

8. Penance V, 2019, paper scorched by hand, 12 x 9 in.

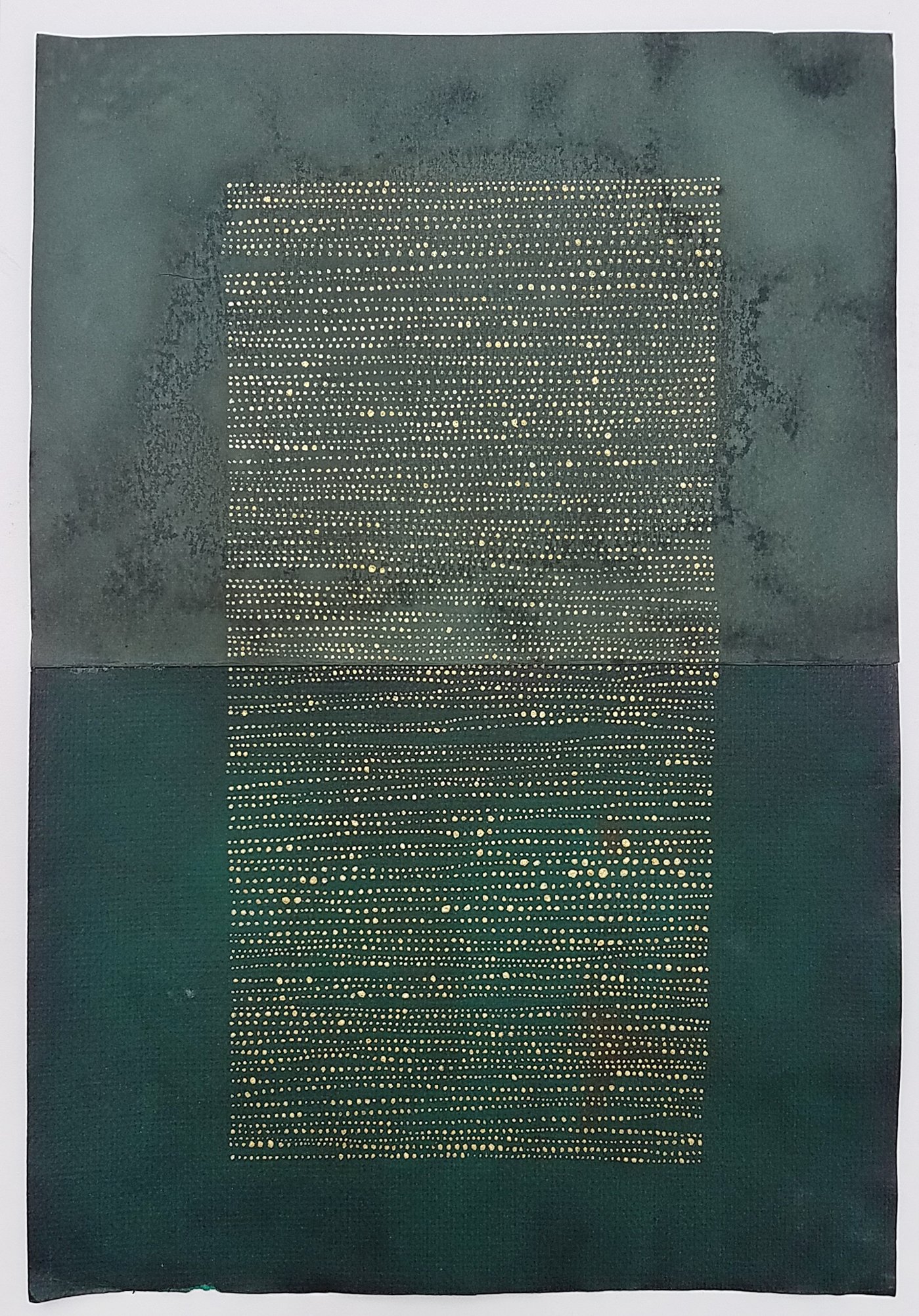

9. Monolith (Gold), 2019, imitation gold on ink-stained paper, 28 x 18 in.

10. Nocturne I, 2018, imitation gold on found paper, 17 1/2 x 11 3/4 in.

11. Of Mothers and Sons, 2020, found objects, thread, metal, and railroad tie

12. Stain, 2016, collaborative performance with artist’s son, Grand Rapids, MI

13. Stain, 2016

14. Mark: Knot, 2015, performance tying knots in red string, Grand Rapids, MI

15. Transfer Water, 2014, performance transferring water between two buckets, Grand Rapids, MI

16. Traces, 2014, collection of photographs of roadside crosses marking death sites, found objects, food

17. Voces, 2009‐2013, performative installation

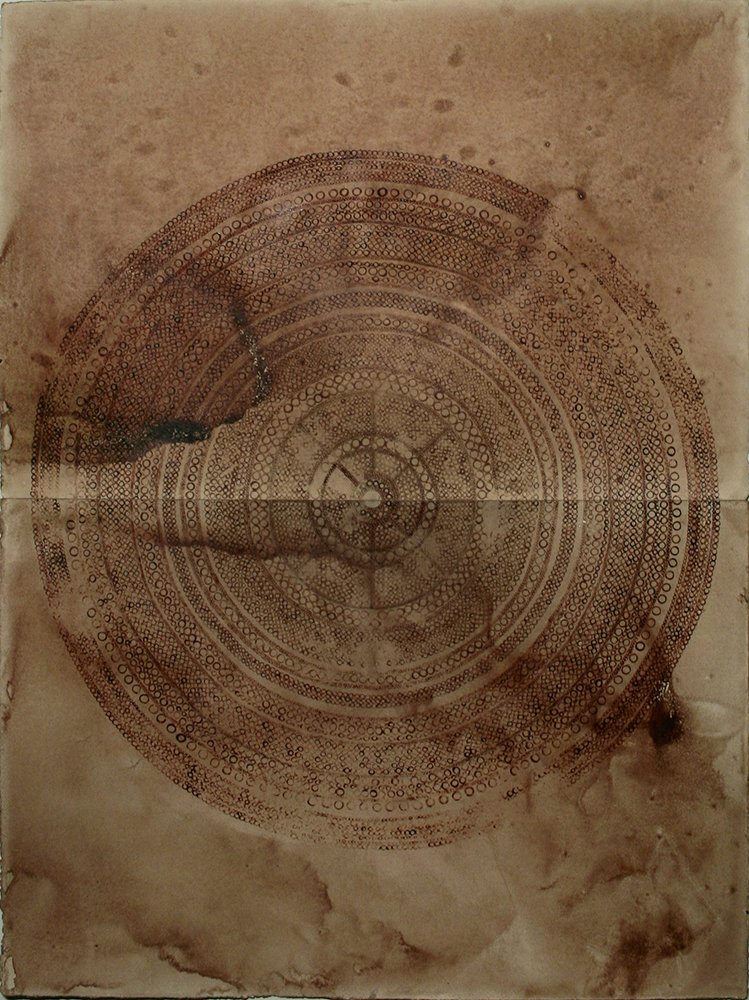

18. Sisyphus IV, 2014, pig blood on paper, 22 x 17 in.

19. The artist in her studio (on Zoom).