Alexandra Rutsch Brock is an artist, curator, and art educator, not necessarily in that order. Whether showing me her new series of sculptures or talking about taking her high school art class to the Met, she exudes passion and a sincere love for making and sharing art. Alexi has curated many shows, including HyperAccumulators and Insomnia, both at the Pelham Art Center in Pelham, New York. “I love shining a light on other peoples’ work”, she says, and indeed, she is as excited talking about other artists’ work as she is about her own. It’s unusual to encounter an artist so preoccupied with and committed to the promotion of others. I’m honored to shine a light on this remarkably generous artist, who sent me home with my very own ceramic vagina, pictured above.

MH: There seem to be three categories to your art practice: artmaking, curating, and teaching. Is there one category that resonates most strongly with you? Or are they all of a piece?

ARB: They’re equally important to me, and they feed each other. I love working alone in my studio, but I also like working with other artists. I started curating when I was 18, and I’ve always loved interacting with artists, visiting their studios, seeing what inspires them. When I was growing up there were always artists in our home, so I thrive on being around creative, smart people. That’s why I love teaching – the kids are amazing, and every day I’m fed by their creativity.

MH: I’ll start with artmaking. Why are you an artist? I know that your father was an influential artist – did he push you to go in that direction, or did you find it on your own? Did you ever resist the artist’s path?

ARB: Both of my parents were artists; my father was more well-known than my mom.* I grew up in this creative environment where there was art everywhere, and we always had art materials to play with. I was good at art – I never wanted to do anything else, and never considered another profession. I was encouraged to go to art school, so I went to SVA (School of Visual Arts, New York) for my undergrad. I later got my degree to teach art.

MH: You seem to work in series, which I find interesting. Do you see your explorations as a single continuum of creative expression, even though one series is quite different from another? Does one series lead to the next?

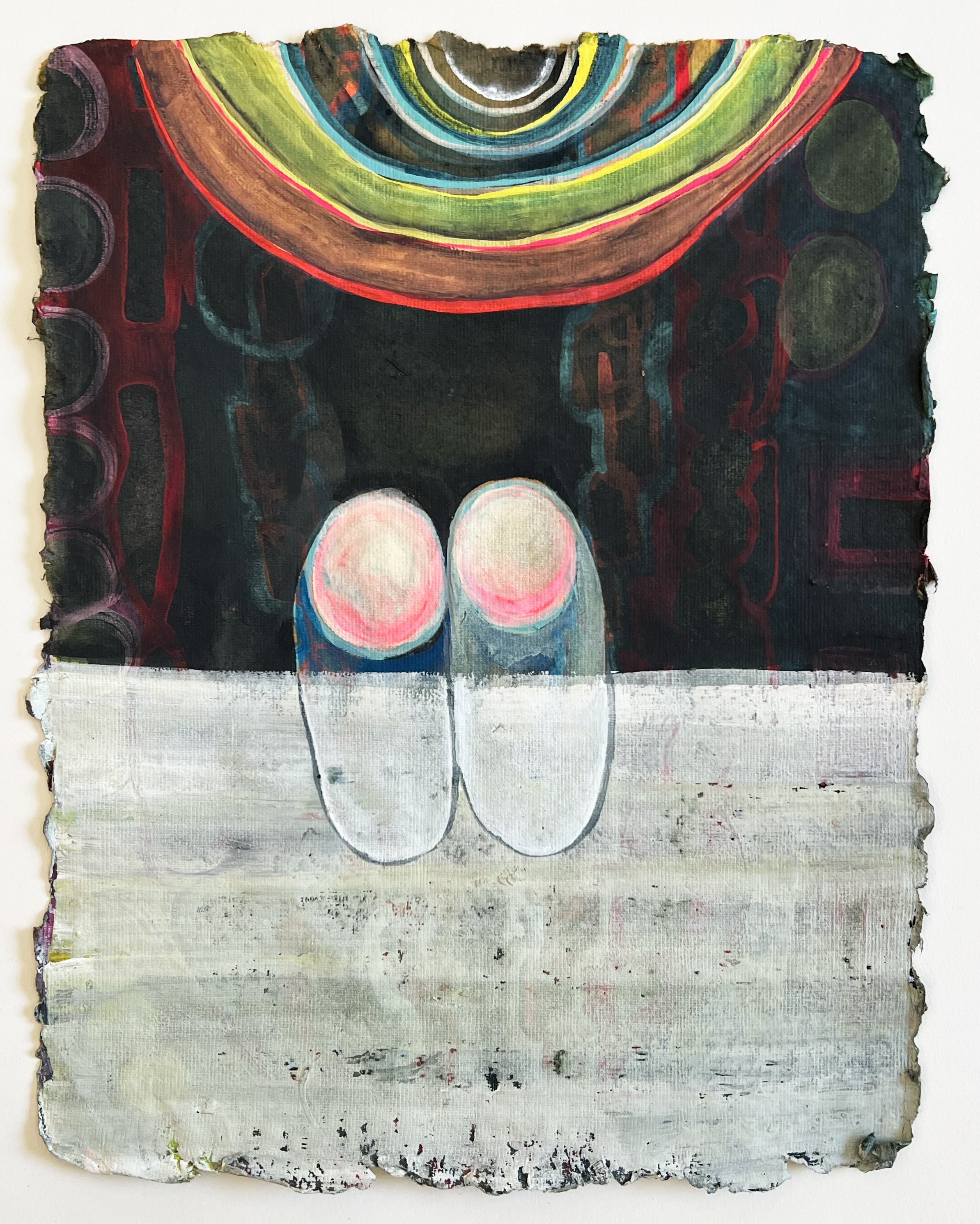

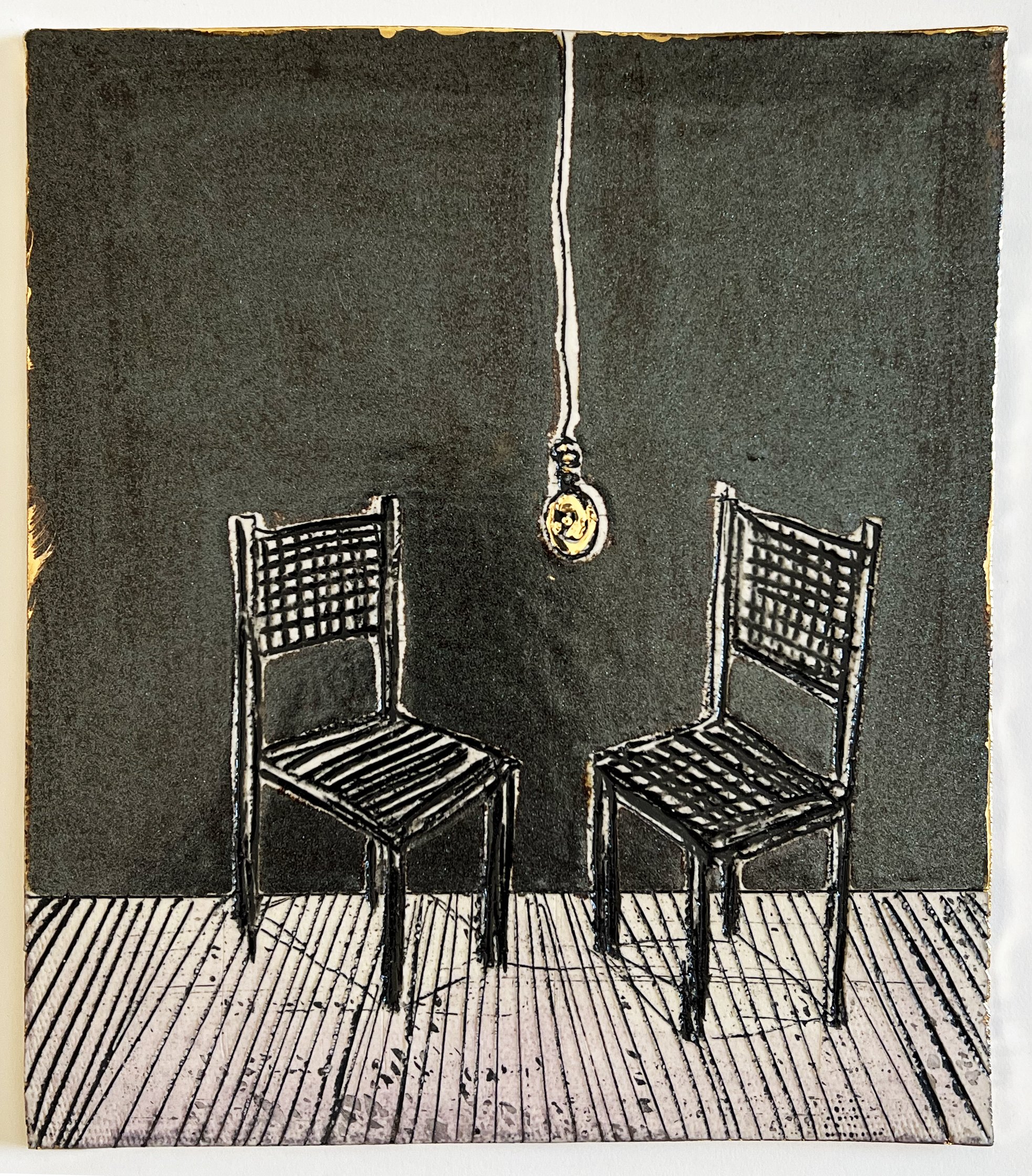

ARB: All of my studio work is about me and my life experience, so it’s all connected. The various series have to do with birth, sickness, heart surgery, cancer, aging; the medium varies but it’s all about my life. In a larger sense, it has to do with the fragility of life, the frailty of our bodies, loss, and vulnerability. Commercially speaking, working in so many styles and mediums is problematic, but in an artistic sense it’s not. It’s hard for me to continue with a series after I’m done with it. Once the initial excitement is gone, I have to end the series because the soul leaves the work and it gets too clean and polished. I want the work to stay raw. I want it to be art, not a product.

MH: Some artists choose to explore deeply within the parameters of their medium and subject matter, like Rothko, for example. And then there are artists who like to experiment with different styles and concepts – Gerhard Richter comes to mind. Does either approach resonate with you?

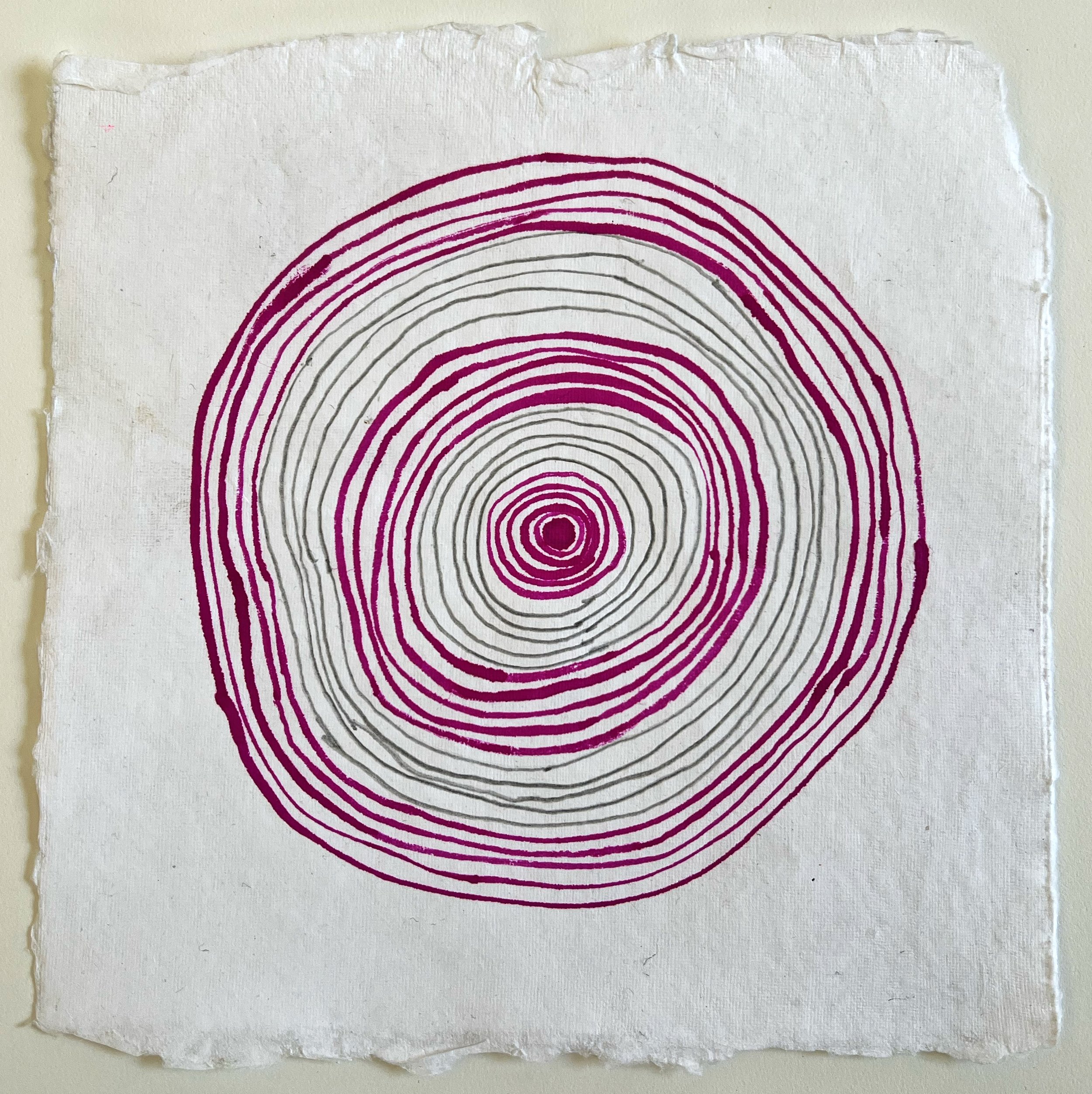

ARB: I like exploring a lot of ideas, and I like to break the rules of a medium. It’s the mark-making that I’m interested in. For me it’s all about the exploration – that’s what I find exciting and fun. I have an idea, or something speaks to me, and I figure it out as I’m making it. And then once I figure it out, I’m usually done with the series.

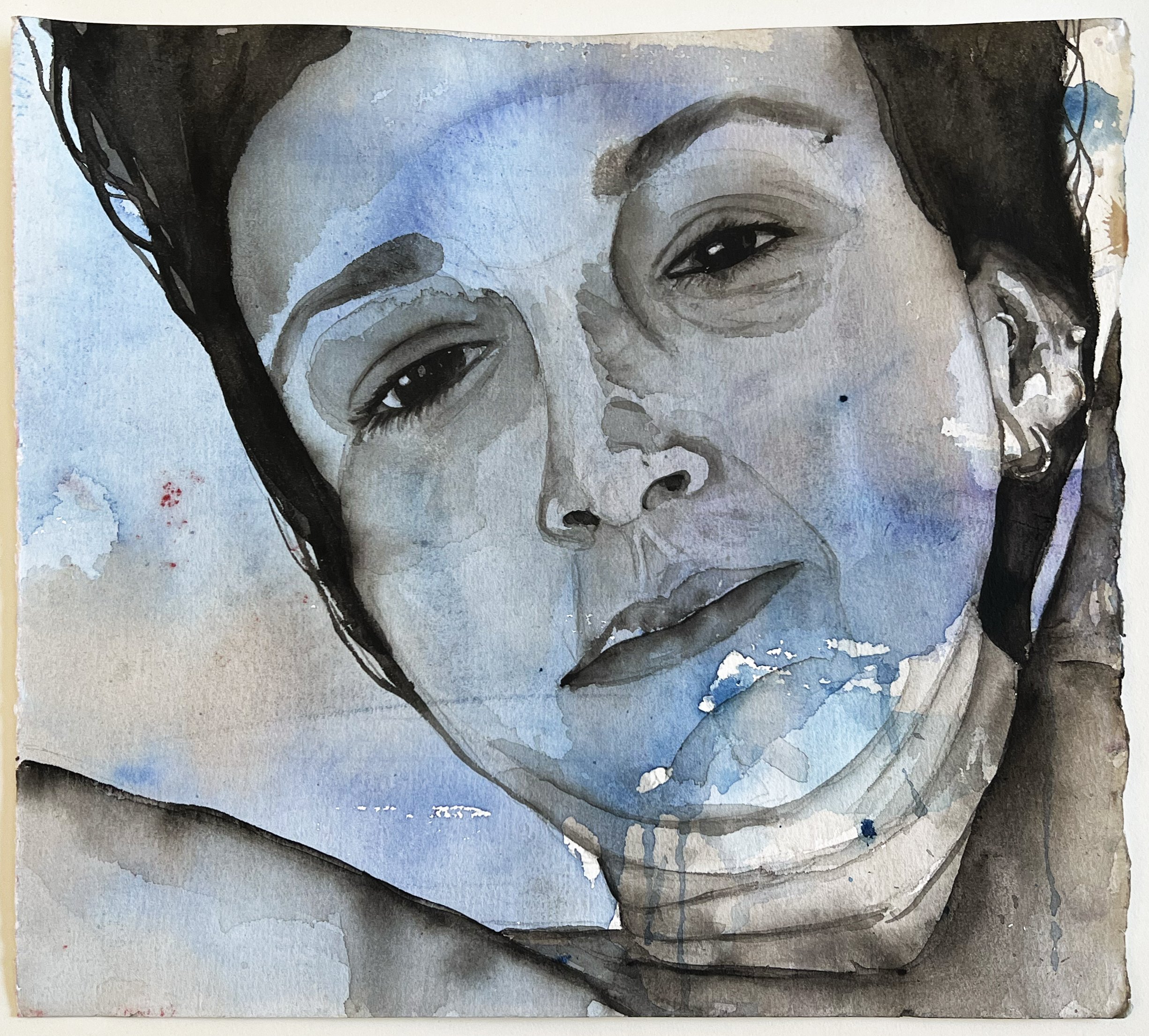

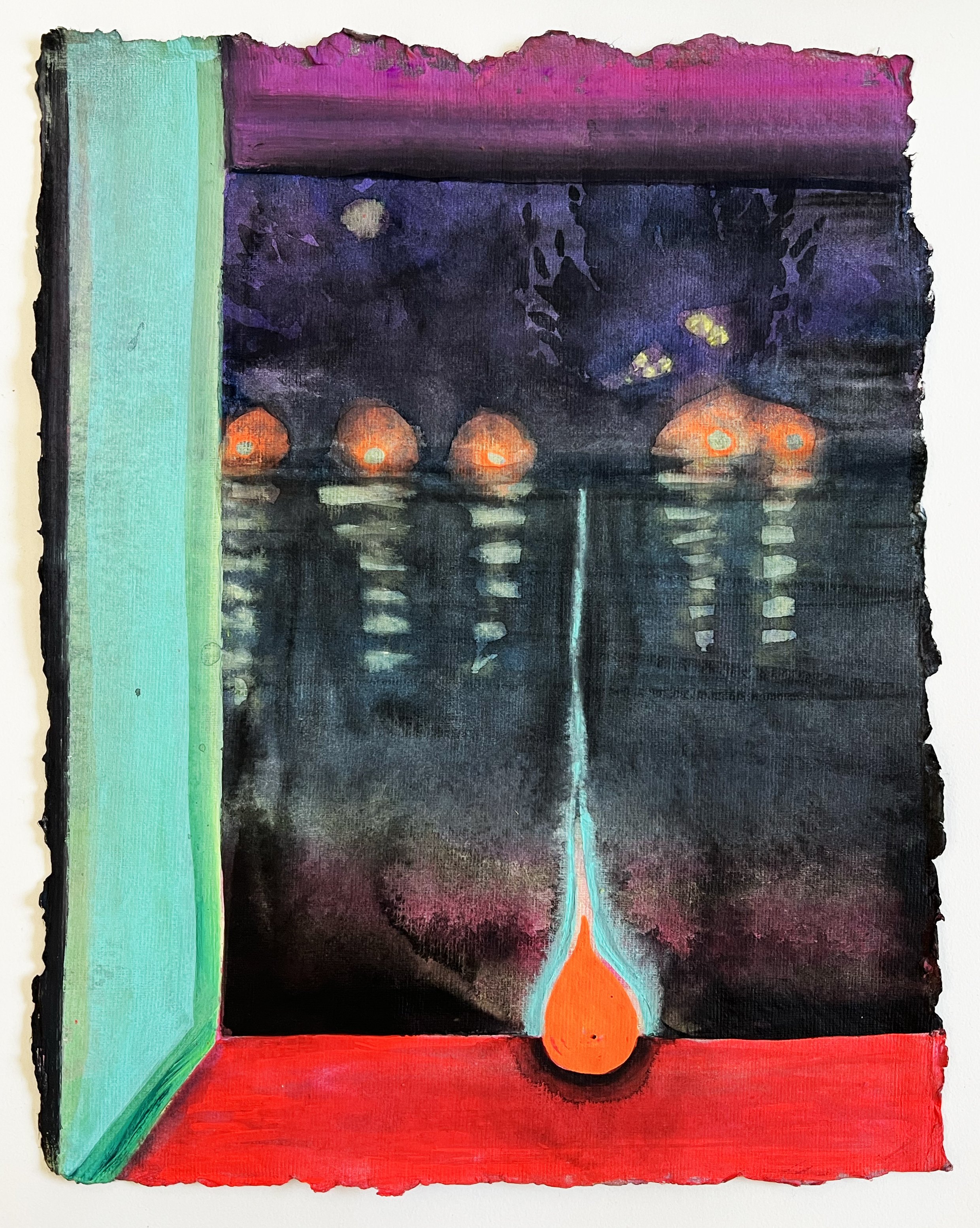

MH: My favorite is the Ecstasy series, which are some of the most vulnerable portraits I’ve come across in a long time. They appear to be portraits of women in orgasmic pleasure, but I love their ambiguity: are they alone? Is there a lover? Maybe she’s in the agony of childbirth? Whatever’s going on, the tenderness is deeply felt and communicated.

ARB: They’re all me. I painted them from photos that my husband took, experimenting with stained paper and gouache. I wasn’t trying to be pretty; in some I look ugly or wounded. This series just flowed out of me, and several people suggested that I make them larger, but I couldn’t. They’re the size that they’re supposed to be, which is life-sized.

MH: You said that you have a new series going. Can you talk about that yet?

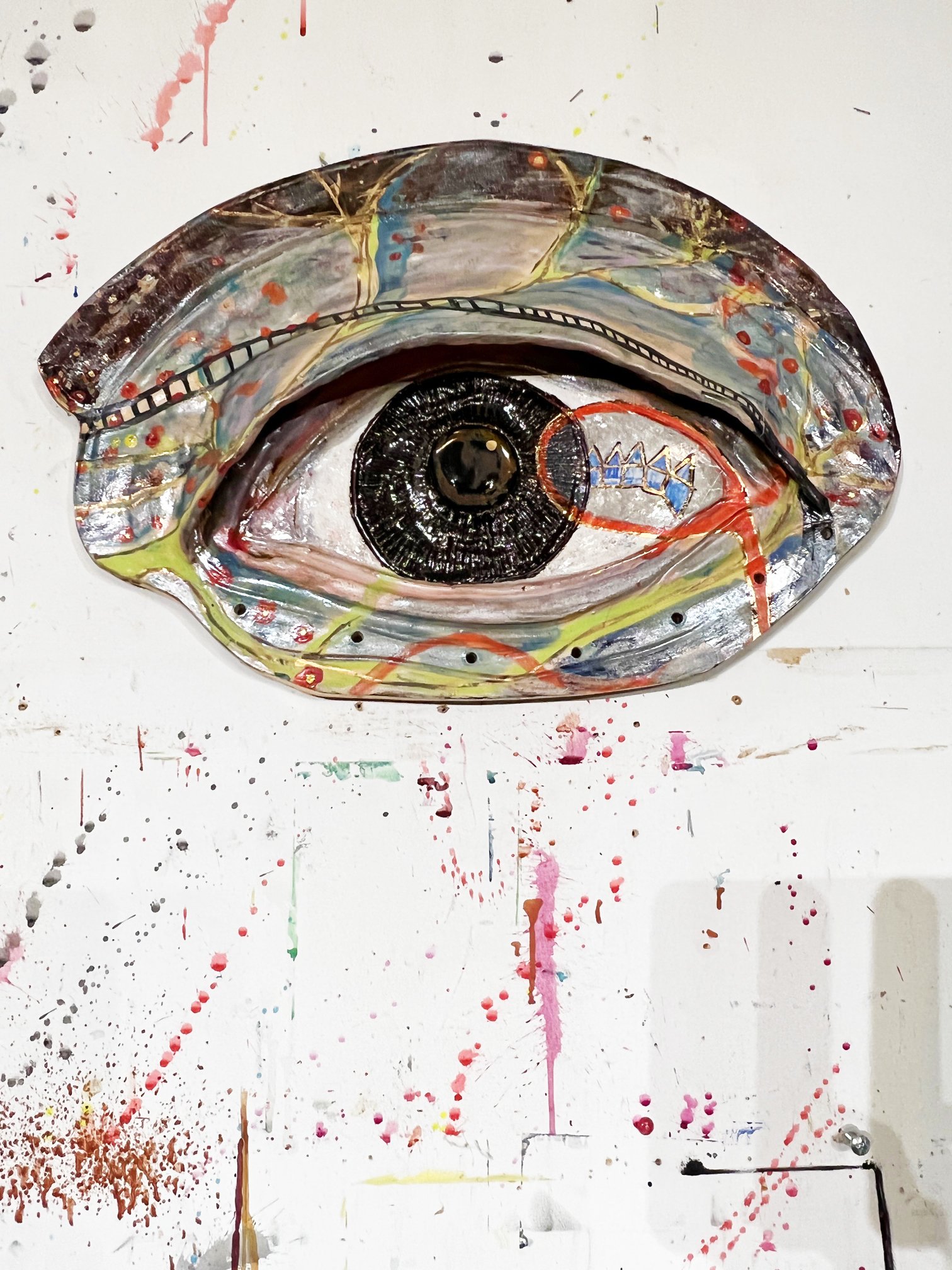

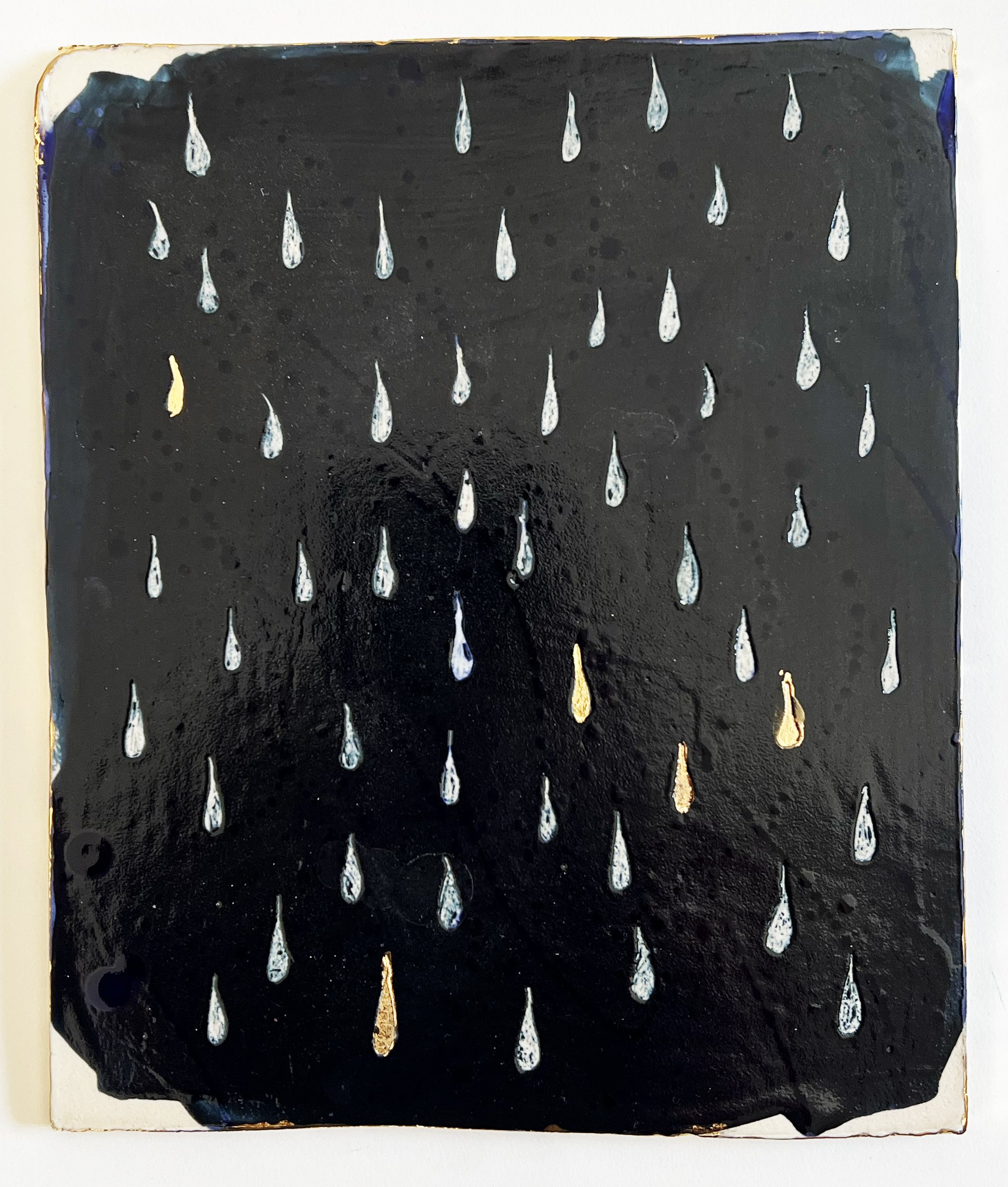

ARB: I did a series of crying eyes during the pandemic. I started out by drawing eyes, then I sewed eyes on paper, and eventually I made them more tangible by sculpting them in clay and adding the tears. It was about the collective mourning of all that we were losing, and about some personal loss as well. The last five years have been filled with intense changes for me, so the tears are about loss, nostalgia, and losing control.

MH: Curation and collaboration play a big part in your art practice. Does it satisfy a different part of your creative drive? What is it about community-based work that you find gratifying?

ARB: I love the whole process of curating. I like meeting the artists and doing studio visits, I like putting artists’ work together and planning a show, and I like working with other people and coming up with ideas for shows. The conversations that artists have about art is always interesting – I mean, that’s the best energy in the world, right?

MH: Curating is interesting when you’re an artist, because you put a show together, but it’s not your own work. So there’s this once-removed gap that might mitigate the vulnerability of showing one’s own work. Does this ring true for you? On the other hand, it must be super gratifying to shine the light on another artist’s work.

ARB: This is what I love about curating! I love shining a light on other peoples’ work. I love putting artists together and starting a conversation about art and ideas. And of course it’s easier to approach a gallery when I’m not asking for myself, but asking them to look at another artist’s work.

MH: Do you think it takes a certain amount of arrogance to be an artist? Maintaining a studio, forking over money for art supplies, dedicating one’s free time to express oneself – all of this requires some serious self-confidence. Do you ever struggle with this?

ARB: I don’t think it takes great confidence to buy art supplies and make work. I don’t need to struggle with this too much because I’m making it for myself. It brings me joy. I think every artist does it because they love it. But if I’m struggling with a particular piece, I just switch to another medium. I need to be excited about what I’m doing, and if something doesn’t excite me anymore, then I can’t continue to work on it.

MH: And then there’s teaching. How does that feed into your practice? Is it a calling?

ARB: I love teaching art to kids. I want to show them how good it feels to make something, not so that their work can be in a gallery, but just because it brings them joy. I also want them to be comfortable walking into galleries and museums. When I bring a busload of kids to the Met, I explain to them ahead of time that we’re not going to enter through the school docent program, we’re going to enter through the main entrance, go to the ticket counter, and everyone’s going to pay a dollar for the suggested donation. I want to show them how it’s done so they can be comfortable with it, and know that this place is open to them any time they want.

MH: What is something about your studio work that you’d like people to know?

ARB: My work is about my life experience. I love the process of making it, and I love making it for myself, and…

At this point in our conversation, Polo the dog jumped off the couch, yawned, stretched, and waddled across her Ecstasy series that was spread out across the floor. I semi-freaked out, but she waved dismissively and shrugged it off. We had a good laugh.

MH: Um, it doesn’t seem like your work is very precious to you.

ARB: My dad was like that with his work. It was everywhere, so you couldn’t help but step on it. The work just isn’t that important. What’s precious to me is the time that I have to make it.