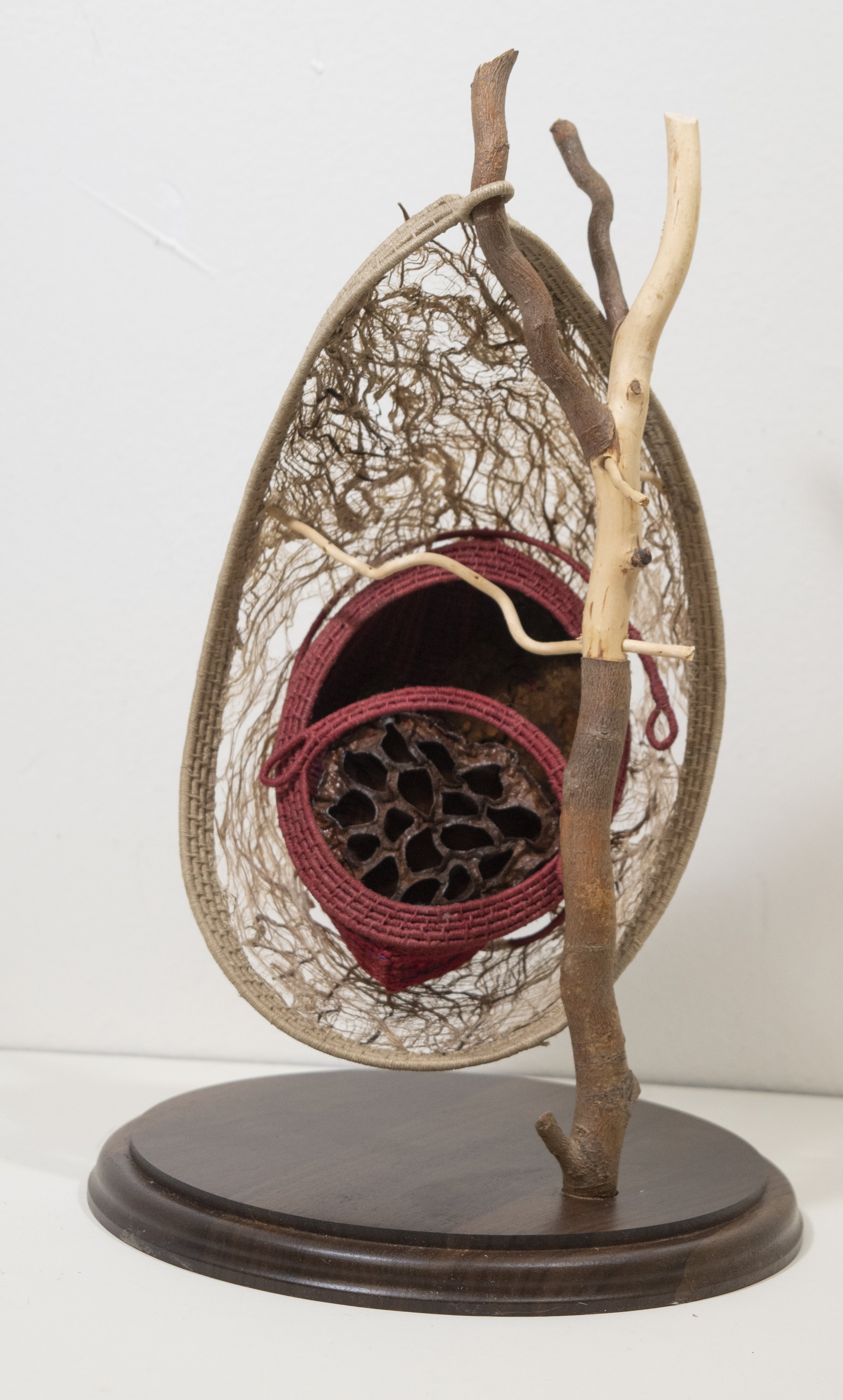

Char Norman is a fiber sculptor, a term that she uses to differentiate her work from fiber arts, traditionally a two-dimensional medium. Her meticulously crafted sculptures are made with natural fibers, handmade paper, and objects that she collects from nature. She is also an environmentalist, activist, and educator, and it would be difficult to tease out the various threads of her practice. Her deep concern for the environment pushes her into activism, which feeds her art practice, which in turn educates her audience about the environment. There’s the sense that her work has a higher calling, and that the white walls of a gallery may not be equal to the task. To that end, she sometimes places her fiber reliquaries in urban niches, where they may be discovered and taken home by the fortunate soul who stumbles upon them. This anonymous generosity is in keeping with the spirit of her work, in which the artist disappears, and the natural world shines through. It was a privilege to engage in an in-depth conversation about the practice of this interesting and accomplished artist.

MH: You refer to yourself as a “fiber sculptor”. What does that term signify?

CN: “Fiber arts” generally refers to works that are two-dimensional, like weavings and wall hangings, but my work is three-dimensional, so “fiber sculptor” is more descriptive of what I do. I create sculptural forms by combining natural fibers with elements from nature.

MH: Your work is nature-based, and nature has played a significant role in your life since you were a child. How did you get so turned on by nature?

CN: I’ve always lived close to nature – even now, I hike almost every day. As a kid my grandfather would take my brother and me on long hikes in the woods. It always felt magical, and that love of nature has been there ever since. It’s where I find peace and refresh myself. Whether it’s the coastline of California or the hardwood forests here in Ohio, it has the same effect.

MH: All your work is skillfully constructed and detail oriented. Do you concern yourself with the current trend toward deskilling? Do you care if skill is currently out of fashion?

CN: Craftsmanship and skill are very important to me. It’s something that I excel at, and I don’t want to lose it. As far as the trend away from skill, I mostly ignore it because it’s not who I am. Every now and then I try to loosen up a little, but it’s hard for me to do. It has to be finished; it has to be precise. I do care that skill is out of fashion because I think it’s an important and satisfying aspect of being an artist.

MH: There’s a lot of repetition in the making of your work – I’m thinking of the coiling, for example. I wonder if this type of work feeds you in some way. Is it ever boring, or would you describe it as meditative?

CN: It can be extremely boring, but it can also be meditative. Most of my work is made up of pods, which require many hours of coiling. When I start a piece, I’m just coiling around and around which is slow and boring, and I usually have to engage my mind in something else while I’m doing it, like listening to music or books. Once I establish the shape of a pod, I’m designing and engineering the piece as I coil, which gets creative and exciting.

MH: I know that you’re a deep thinker, and that your work speaks to some issues that are very important to you. What concepts are most pressing to you? How does your work address these issues?

CN: Everything I do addresses the environment in some way. I think it’s the most important issue of our time, because if we destroy our environment, nothing else matters. I do a lot of research for my work. A few years ago I traveled to the Amazon rainforest to learn how the indigenous people regard the environment. I’ve also become interested in the mycelium network and all that goes on below ground. This is how fungi send out tendrils that feed the trees, and how the trees speak to each other. There’s so much that we could learn from this, as well as from the natives of the Amazon, if only we were open to it.

MH: At first sight, one would regard your work as beautiful, even precious. But looking deeper, it’s often dark and disturbing, like reading the news. Are you good with that? I’m thinking of Colony Collapse, as well as your Egret Series, which refers to the near annihilation of egrets.

CN: Yes, I want that to happen. I want people to be educated and realize what’s going on. If I can entice them with beauty and then show them the dark side, that’s great – that’s a successful piece. The Egret Series is a good example. It grew out of some research that I did when I heard that egrets almost went extinct in the late 1800s. Their feathers were used as adornment for fashionable ladies’ hats, and as a result, egrets were slaughtered and nearly wiped out. But two society women intervened by boycotting the hats, saving the egrets, and forming the Audubon Society in the process. So this is the kind of research that I do when I’m working on a series, and it can be pretty disturbing at times.

MH: Yes, but your work seems fundamentally hopeful. Is this a correct read? Do you think that in spite of devastation and environmental collapse, your work embraces hope? Or do you create relics as nostalgic reminders of what we once had?

CN: I see it as both dark and hopeful, but mostly I want the work to bring awareness to the importance and beauty of the natural world.

MH: There’s the sense underlying your work that you’re making reparations to the planet for the ways that we’ve abused it. Do you see your objects as offerings? Do you ever regard your work as penance?

CN: I regard it in a couple of ways. First, I like to present the work as if it’s sacred, so sometimes I place it in a tabernacle or a shrine. Whenever I go on a residency or travel and create a body of work, I leave a piece behind. I’ll mount it in the forest somewhere, as an offering to nature. I feel that I’m giving back a little. I also do this in cities. When I went to Italy for a residency, I saw that there were tabernacles and niches on almost every corner in Rome and Florence, which were shrines to Christianity. So I started creating little sculptures out of leaves and sticks and fibers, and then I found empty niches and left them there. They were my shrines to nature. And then some of the work is about mending nature, where I sew it back together. I’m fixing it as a sort of reparation.

MH: How do you like having a full-time studio practice? Does it ever get old? Do you sometimes miss teaching and administrating?

CN: I was at Columbus College of Art and Design for 14 years as Dean of Faculty and Associate Provost. I was developing programs and overseeing faculty and doing art accreditation and working a 60-hour week. Do I miss it? Not a bit. I love being in the studio full time. I feel now that I’m doing what I’m supposed to be doing. When I get a little tired of it, like during the pandemic when I was in my studio all the time, I go for a hike, work in the garden – something like that. I also do a lot of curating, which is great because I’m talking to other artists and putting together interesting shows. Right now, I’m working on an environmental show for the Columbus Cultural Art Center. I’ve been working on this show for three years, and it opens this September.

MH: Is it necessary for you to struggle in the studio? Or do work better when the seas are calm?

CN: The struggle comes when I get tired of what I’m doing. I did a lot of shows last year, and it felt like I was producing the same thing over and over. I was thinking of taking a year off, but that didn’t happen. Ideas come fast and furiously, and I have to start them because when the seas are calm, I don’t work as intensely. When my life is in turmoil, I get much more work accomplished. There’s been some trauma in my life over the last decade, and my work has always saved me.

MH: So your work is a refuge, in a way?

CN: Yes. I retreat into the studio and shut everything else out and dive into my work.

MH: Putting aside the commercial aspect of artmaking, how does what we do have value? Beyond gallery shows, beyond sales, beyond Instagram posts, what is it that we give to the world that is essential?

CN: Education. An important aspect of my work is educating people about the environment. But ironically, part of it is that I’m just making more stuff and putting it out in the world. The environmentalist in me thinks maybe I shouldn’t be doing that!

MH: Which do you think has more value: the creative act, or the work of art?

CN: I think the creative act is more important. My sculpture is just going to take up space somewhere, but creativity generates intelligence. It’s a little like the chicken and the egg, because the creative act results in the art object, and then the art fuels more creative energy.

MH: Given what’s happening in Ukraine and around the world, is it even worth it to make art? Does an artist have the power to make a difference in the face of so much destruction? Are we sticking our heads in the sand when we go into our studios?

CN: Yes, but I think we have to carry on. Art is not essential for living, but it’s what makes life worth living. And I think that’s the reason we need to keep making art – to create hope. I read about these Ukrainian women who are making shamanic dolls for peace, and even though they may not bring about peace, it’s important for them to be making them. It provides them some comfort, and it expresses the value of their culture.

MH: Is there something about your work that you’d like people to know, that they might overlook at a quick glance?

CN: The work that I make and the act of creating it are sacred to me. The ubiquitous pods in my work are symbolic wombs and shrouds, and they refer to the circle of life and its sacredness. And yet it’s also very mundane – we live, we die, and that’s the way it is. I’ve often said that when I die, I want all my sculptures to go back into the woods and become one with nature again.