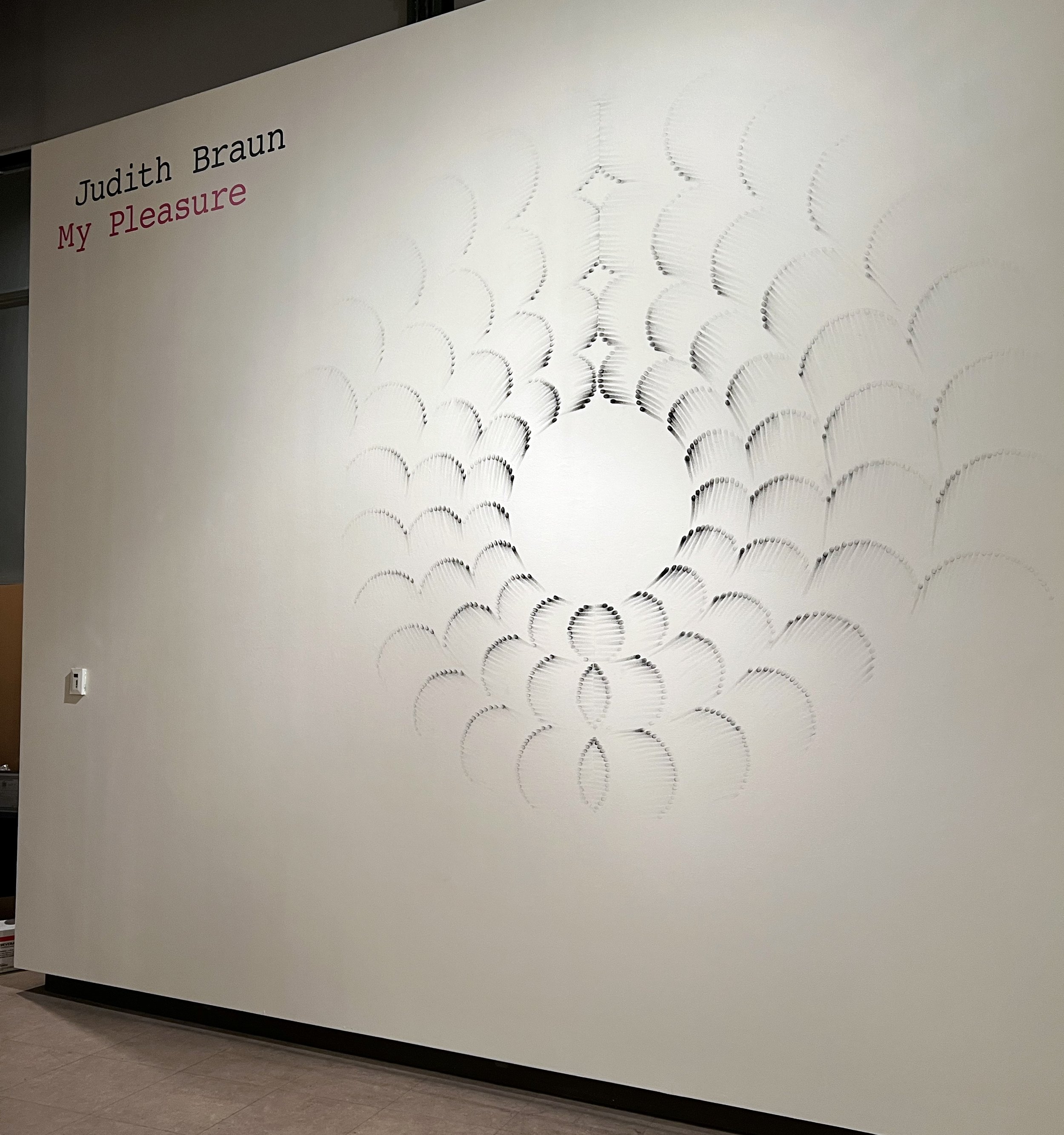

In her various series of drawings and paintings, Judith Braun explores the symmetries of the natural world by filtering them through a series of self-imposed disciplines. This process, which she calls “Symmetrical Procedures”, is based on three rules: symmetry, abstraction, and carbon mediums. That may sound wonky at best, or self-punishing in the extreme, but after listening to her rationale, I became a devotee. Like a levelheaded apologist, Braun expounds on the philosophy behind her work with reason and conviction. “I think of it as freedom through discipline”, she said, and it’s clear that she employs her practice outside of the studio as well. Braun applies the same stringent parameters to her small graphite drawings on paper as she does to her ephemeral fingerprint wall drawings, which have been commissioned across the country and in Europe. The restrictions help to push her deeper into her creative work, which in turn illuminates the symmetry of the universe and her place within it. I went to the opening of her solo show, “My Pleasure”, at Opalka Gallery in Albany, which features her new series of fifteen large-scale self-portraits. These paintings on raw canvas appear to be a departure from her past work, but during our conversation she revealed their origin, how they evolved, and how they are indeed a continuation of the discipline that she’s been using for almost two decades.

MH: Your show “My Pleasure” at Opalka Gallery is a big departure from your past work, in style and scale. Can you say a few words about the show, and how it came about?

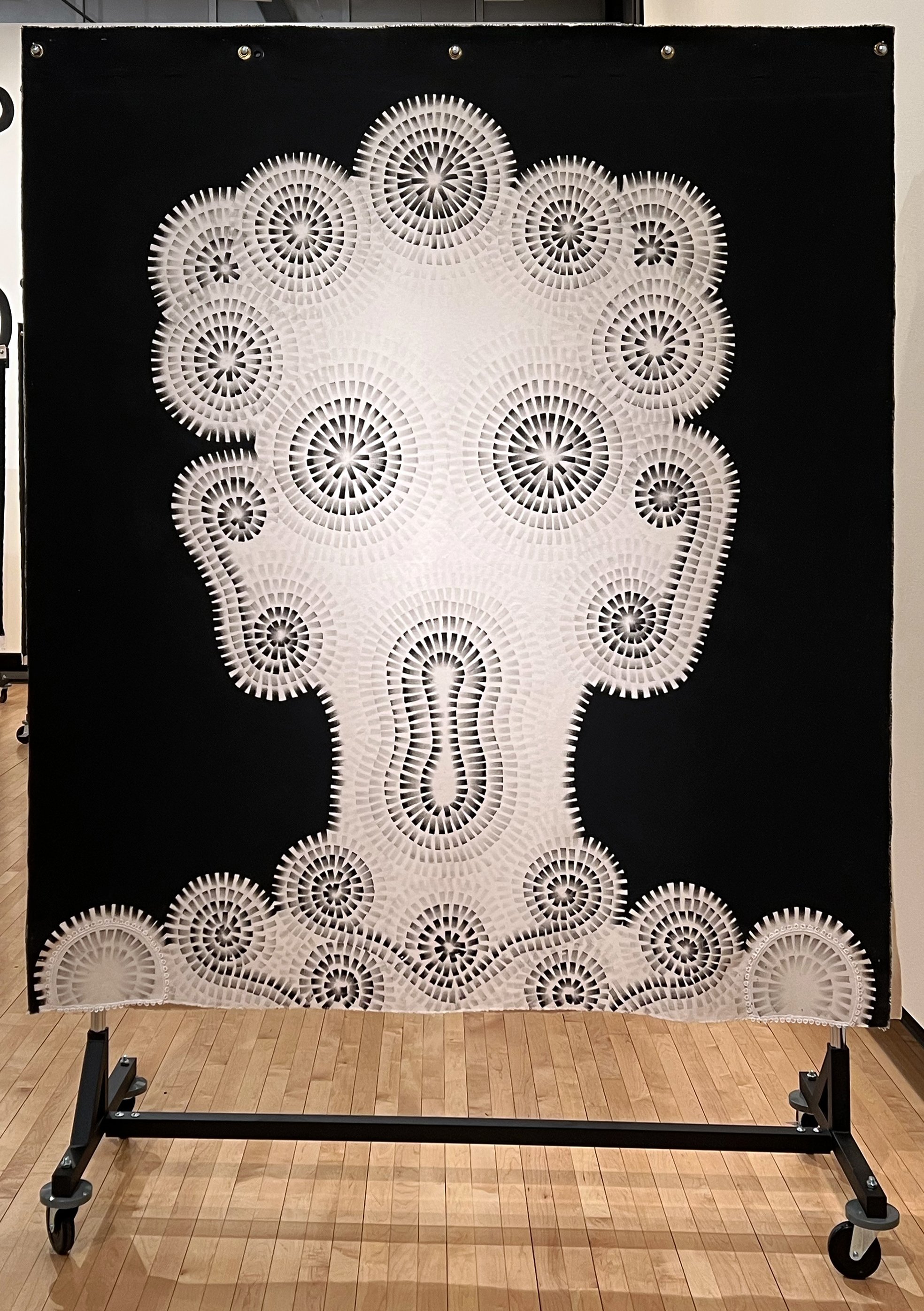

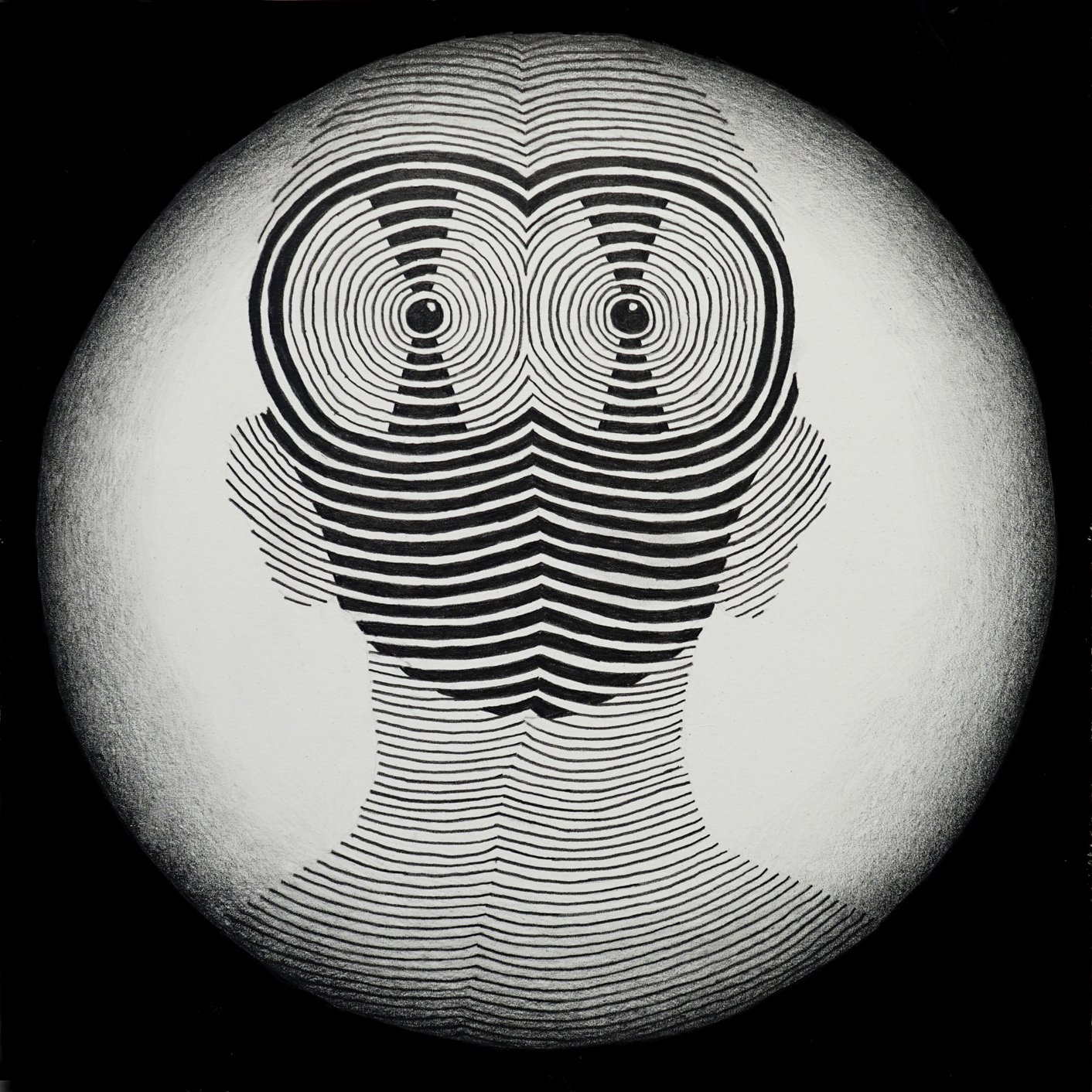

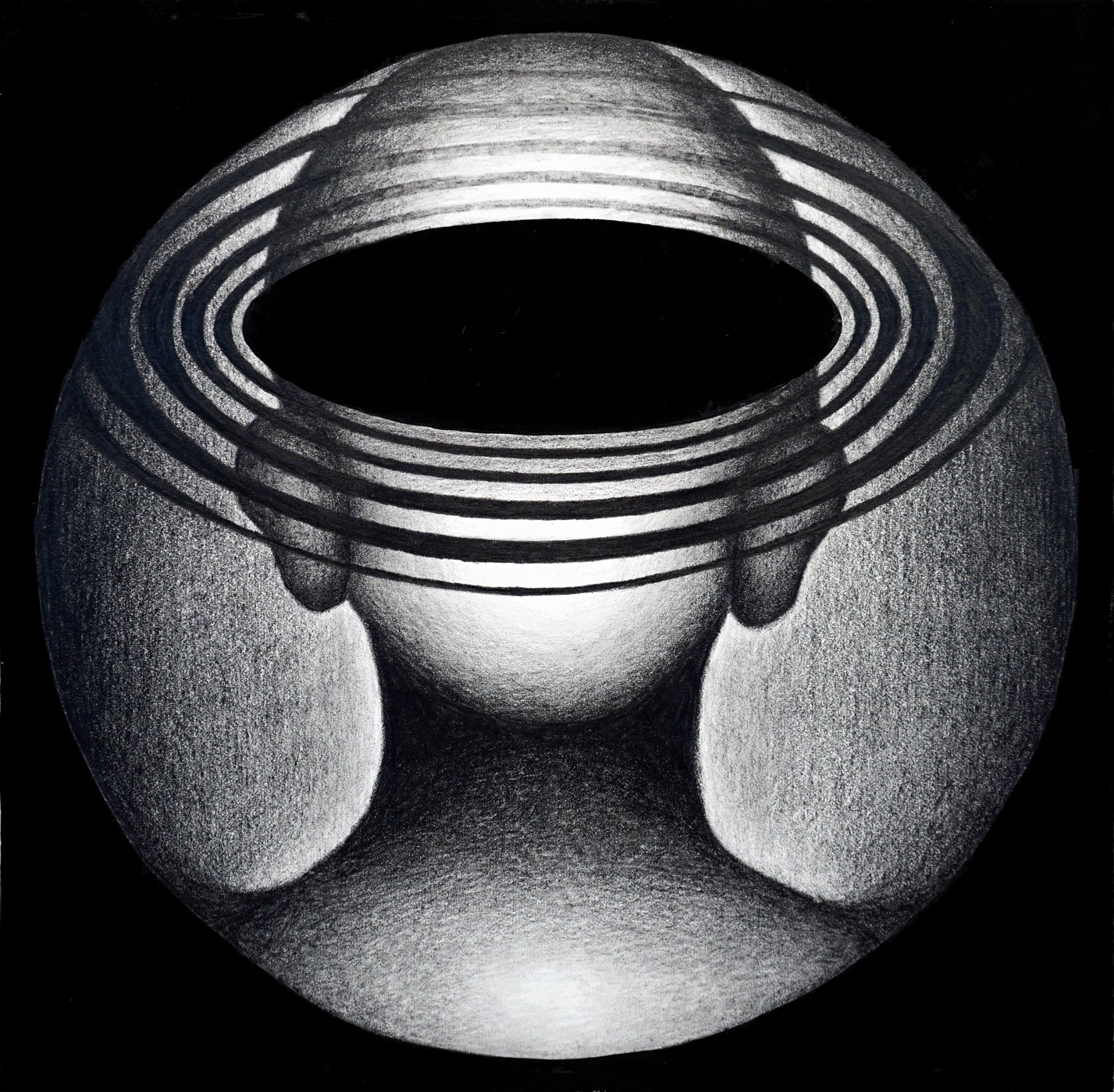

JB: I was making small drawings during the pandemic, and I wondered what they would look like if I did them on a large scale. I did some experimenting with raw canvas and black flashe paint, and I liked how it looked and felt. Using a brush on raw canvas had a similar feel to graphite on paper. It may seem like a departure from my previous work, but it has many similarities and follows the same parameters that I’ve always used.

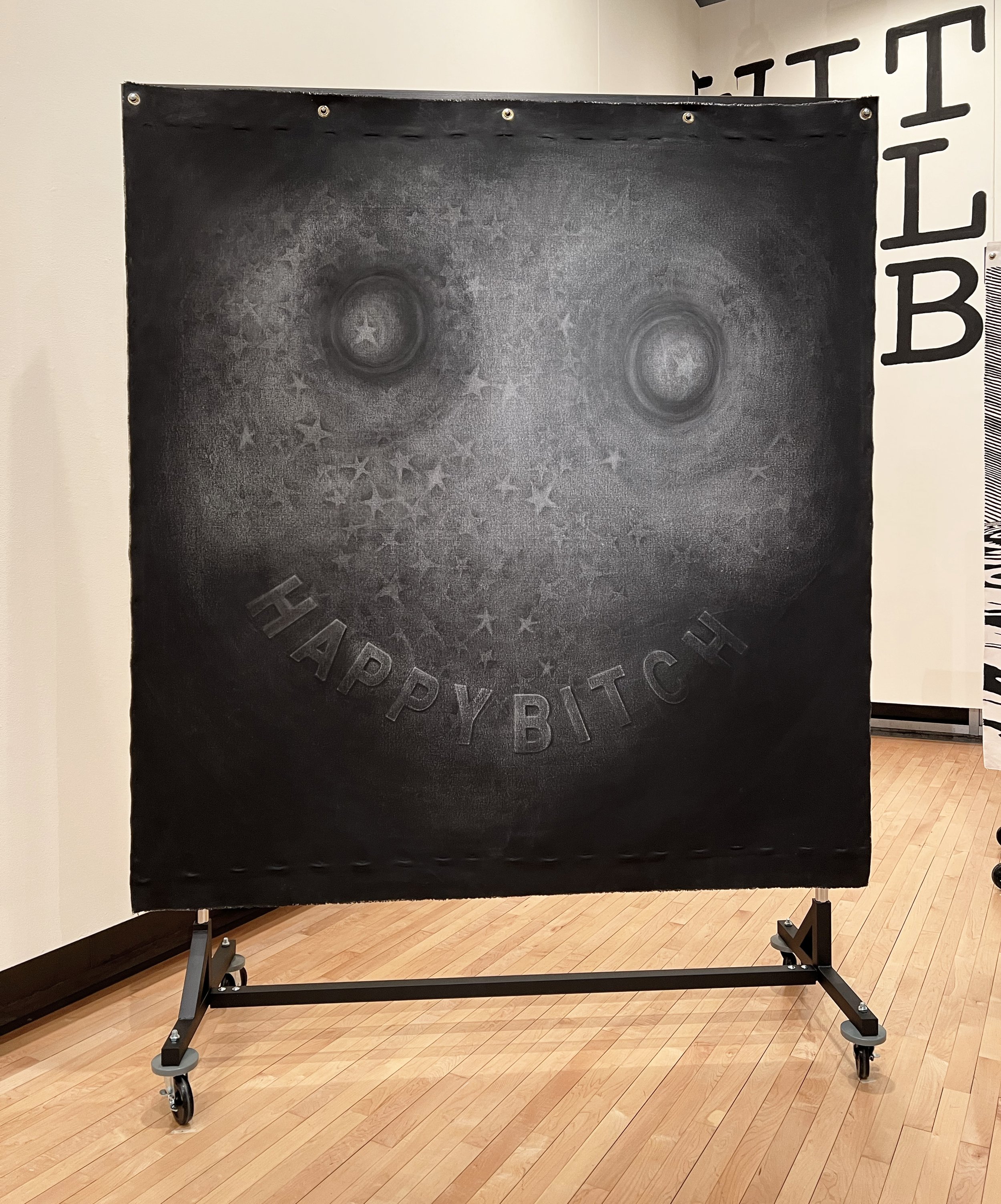

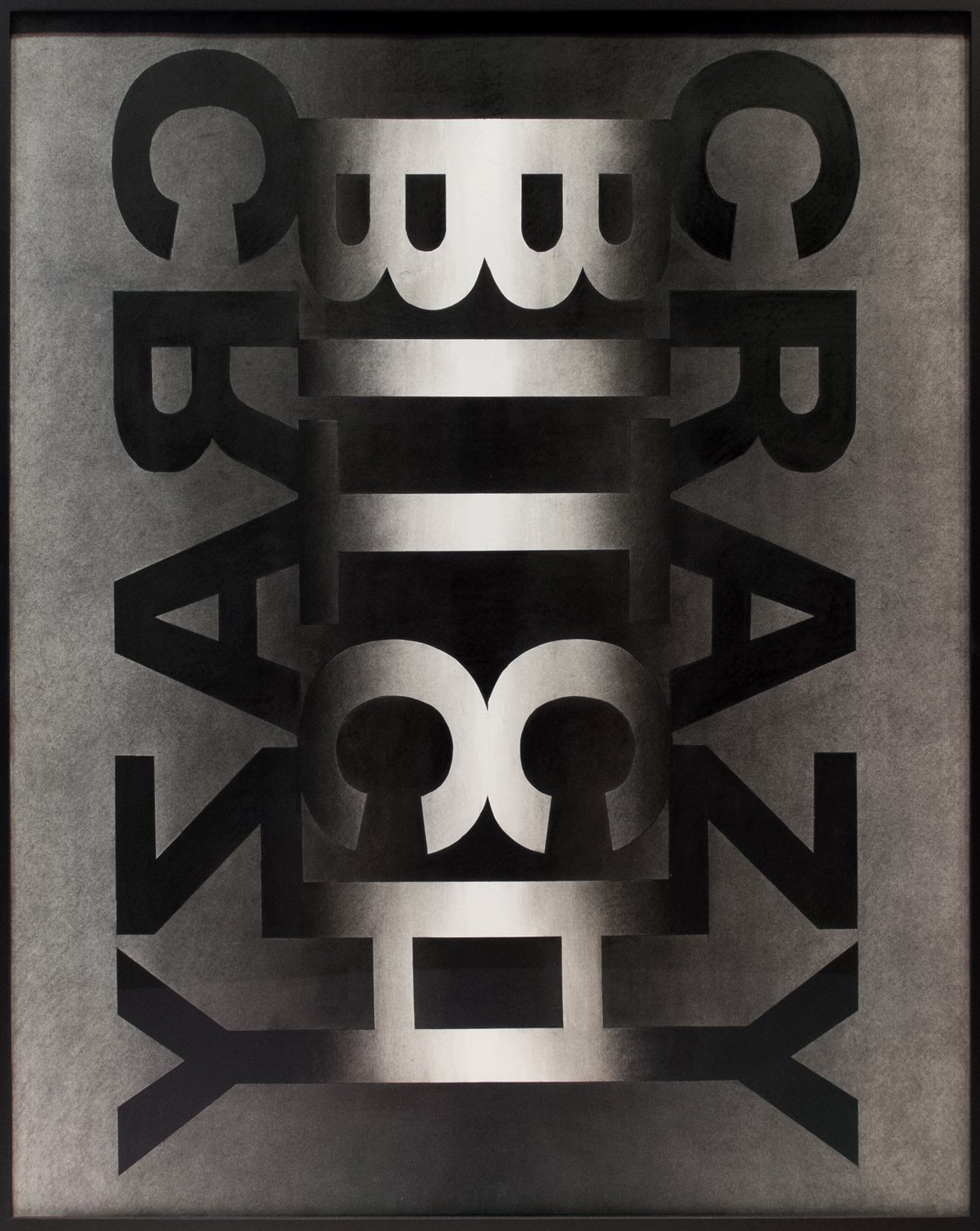

MH: What does “My Pleasure” refer to?

JB: I like words that have some ambiguity. “My Pleasure” is a common response when someone thanks you, and I like it because it feels formal, but kind. At the same time, the title speaks to the whole idea of pleasure, which is a subject I find interesting and provocative. If we didn’t have pleasure, we’d have nothing; we’d just be robots. I used one of my quotes from 2009 for the show and painted it on one of the walls: Without pleasure, all we’d have is a bunch of stuff.

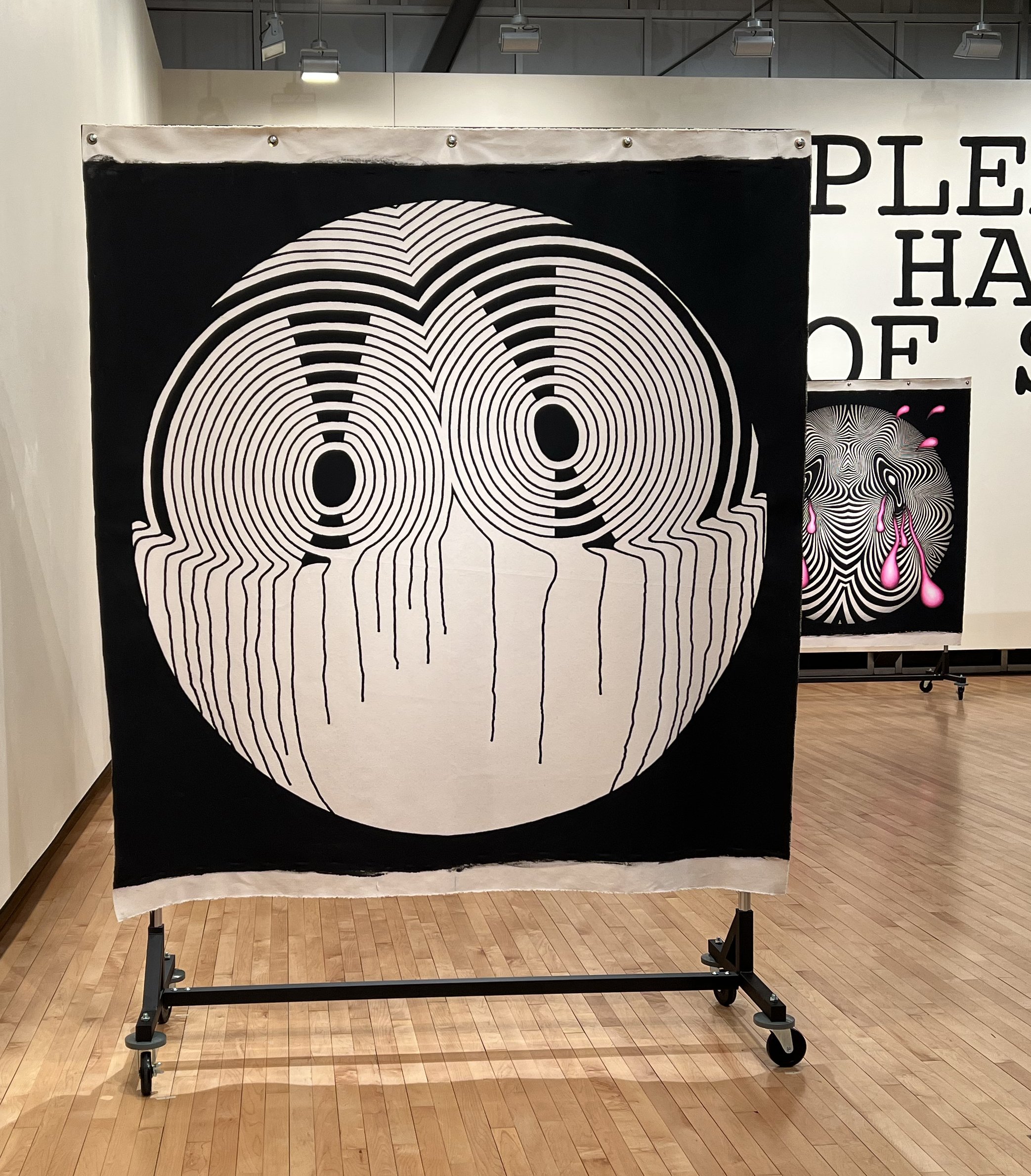

MH: What are your thoughts around the installation? It was interesting to wander through the work, rather than walk up to the wall to see it. I’m curious why you chose to hang the canvases on movable racks, rather than on the walls.

JB: When I started making the work, it became clear that they were becoming big heads. When I tried to picture how I’d install them in the gallery, it felt like they’d be staring in at the viewer in a confrontational way. I did some research and looked at how other artists present works on loose canvas, and eventually came up with the idea of garment racks on casters. I liked the aesthetic, but didn’t know what it would look like in the space, so it was a big risk. But I felt like, why not take a chance? And I like it! It was a big leap, but sometimes you have to take that risk.

MH: How has your relationship to your work changed since leaving New York City? In the city there can be a grind to show and sell your work, which can suck the joy out of an artist’s practice. Was this true for you, and has this changed since your move to Albany?

JB: When I left New York I could have stayed with the last gallery that I was with, but I decided that I wanted to be on my own. I don’t want expectations to be set on me, where a gallery wants a certain type of work that I may not want to create. The compromise doesn’t offer enough to make it worthwhile to me. When I first moved up here, I considered letting it all go, and being an artist who doesn’t show her work. But I realized that it’s just not the same – it’s like talking to yourself all day. I like being part of the art world, which means that I need to engage in it, and it’s a little more difficult up here in Albany. I can’t rely on things happening by chance the way they do in the city, so I actively reach out and try to stay connected with people and galleries. And it helps that I have some traction as an artist, since I showed in New York for so many years.

MH: Can you say something about the parameters that you refer to? You call your practice “Symmetrical Procedures”, a discipline in which you follow self-imposed limitations for making your work. I find it intriguing that in the face of pure freedom of expression, you create restrictions for yourself.

JB: I think of it as freedom through discipline. It’s a philosophical idea that I came up with years ago when I was a hippie and questioning freedom in general. I felt that freedom without self-discipline would just lead to chaos. For me, freedom meant the freedom to choose, and this included the choice of self-limitations. So “Symmetrical Procedures” is the application of that philosophy in a visual medium. I use the disciplines of symmetry, abstraction, and carbon mediums, and I’ve worked within this discipline since 2003.

MH: What do you like about working in this way? Why these three disciplines?

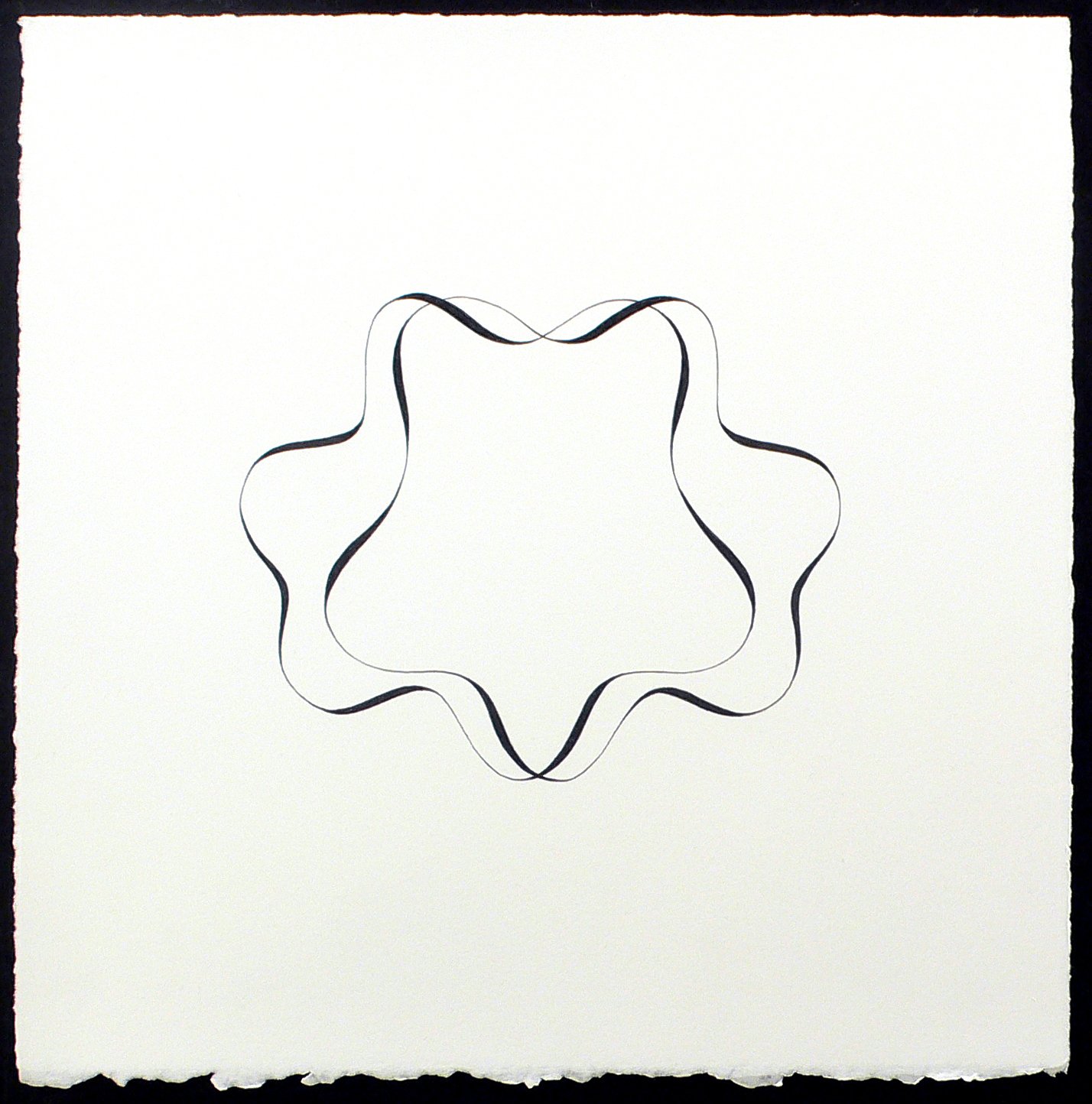

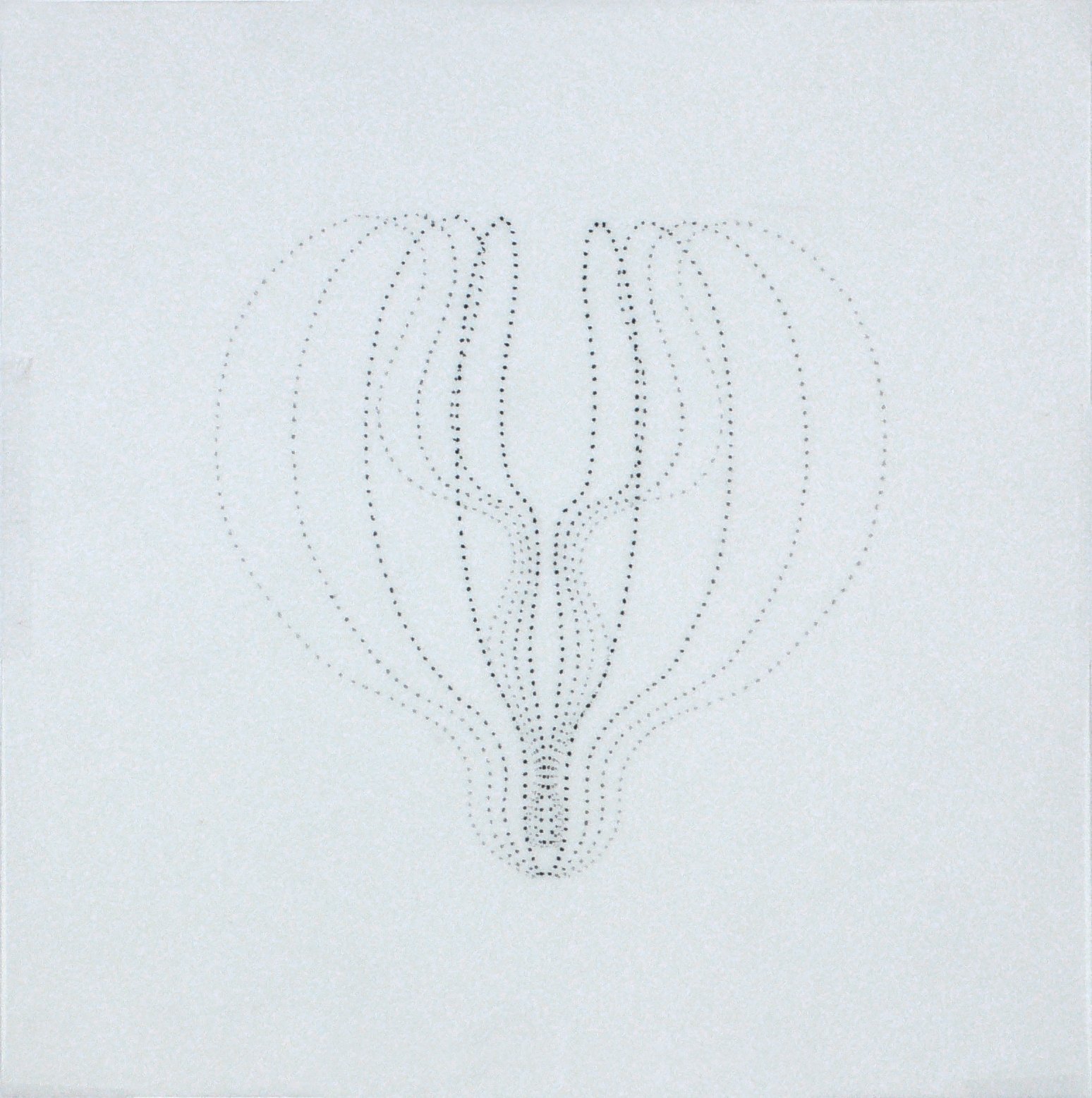

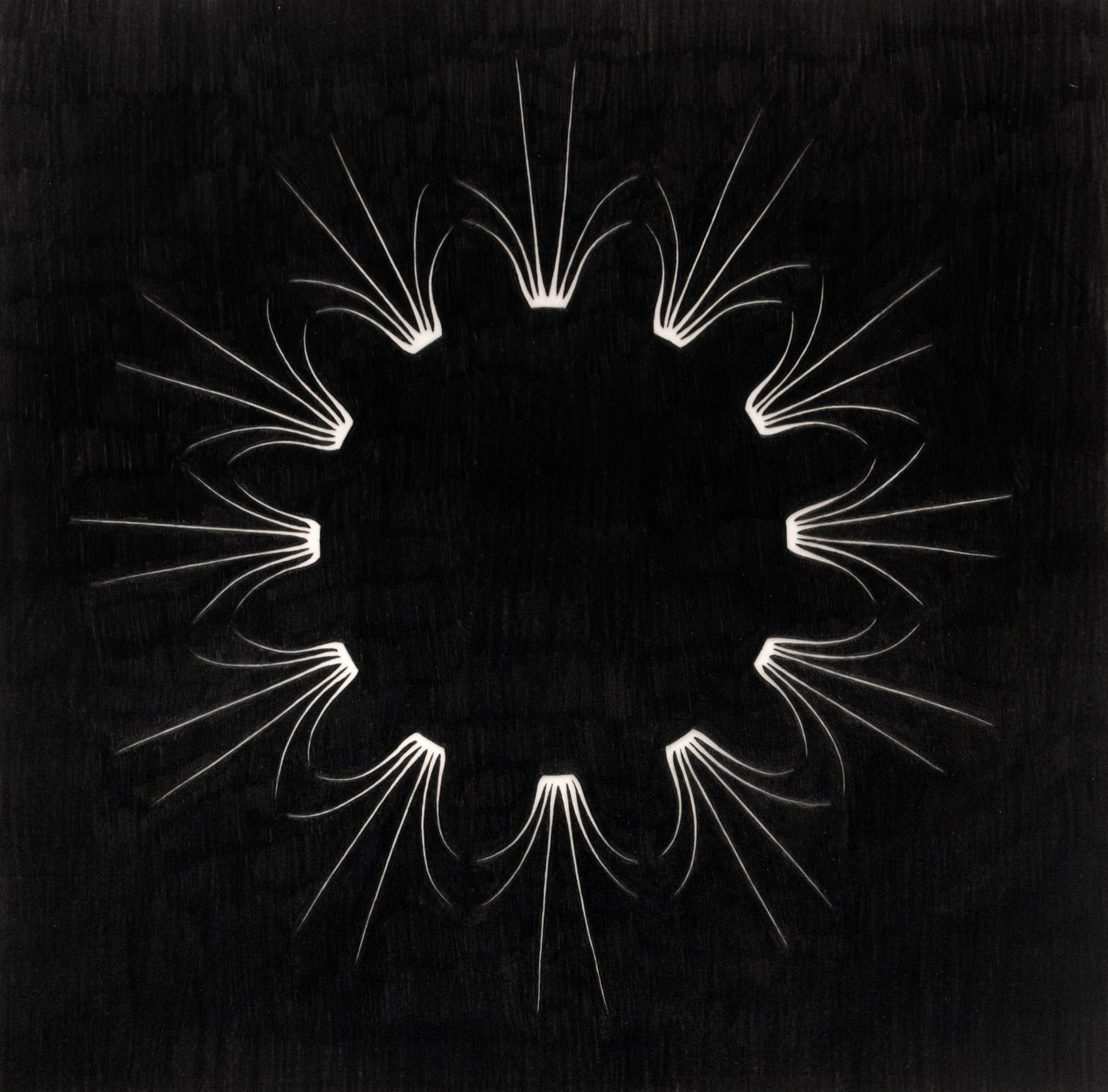

JB: I like working within these parameters because they’re my rules and my ideas; I set it up and believed in it and believed that it would keep unfolding, and it hasn’t gone dry yet. As far as my choices, I chose symmetry because it’s a pattern found throughout the universe, and it’s basic to humanity. And then I chose abstraction because it represents anything and nothing; it has no reference outside of itself. So when I combine symmetry and abstraction, I create something out of nothing. I make a random mark, and copy it in reverse using symmetry, and suddenly I have something. Anything becomes something. Then to all this I added the discipline of using carbon-based mediums, which limited my palette to black and white. I like the fact that under heat and pressure, carbon becomes a diamond, so I’m drawing abstract symmetries with diamond dust.

MH: Does this apply to your fingerprint wall drawings as well?

JB: Yes, they’re also drawn with carbon. I dip my fingers in charcoal dust, and make marks on the wall in a symmetrical pattern. They derive from the same set of rules.

MH: Do you use this discipline as a tool for discovering deeper meaning in your work? Do the self-imposed rules give you something to push against, so that your creativity can flow freely? I’m thinking of the way that riverbanks place restrictions on the flow of water, so that it becomes a river rather than a swamp.

JB: Yes. Another metaphor is the piano. It has eighty-eight keys, and the pianist has ten fingers, but no one has ever thought that they were going to run out of things to play on the piano. The restrictions push you deeper into the body of work that you’re doing. Otherwise, an artist goes into her studio, and she can do anything, with no limitations, and this may not feel like freedom. I have my three disciplines, I chose them consciously, I’ve stuck with them, and they’ve proven over time to have infinite potential.

MH: Could your practice be considered a search for Truth? Do you ever think about objective truth in your work, or is it a non-issue? Has truth become something so quaint, out of fashion, and overrated that we no longer take it seriously? Sort of like realist painting?

JB: I think I gave up the search for objective truth when I moved away from realist painting. I gave up verisimilitude because it required focusing on a level of skill that became uninteresting to me. Now it’s more about the truth of who I am. One of the things that I really like is the unique voice of an artist. Even if I don’t like their work, I can appreciate their authentic expression. I’ve come to think of truth as being true to myself. And that’s what I wanted this show to be – a part of me that I haven’t shown before, but another part of myself that’s true.

MH: Art has always reflected the dominant beliefs of the culture. I’m thinking of Renaissance art, which portrayed truth as indisputably objective, and Modernist art, where truth was depicted as entirely subjective. Does Post-Truth Art reflect the gray zone of “alternative facts”? When there are so many conflicting narratives, I wonder if the artist may increasingly turn inward, where the work becomes hyper-self-referential. What do you think?

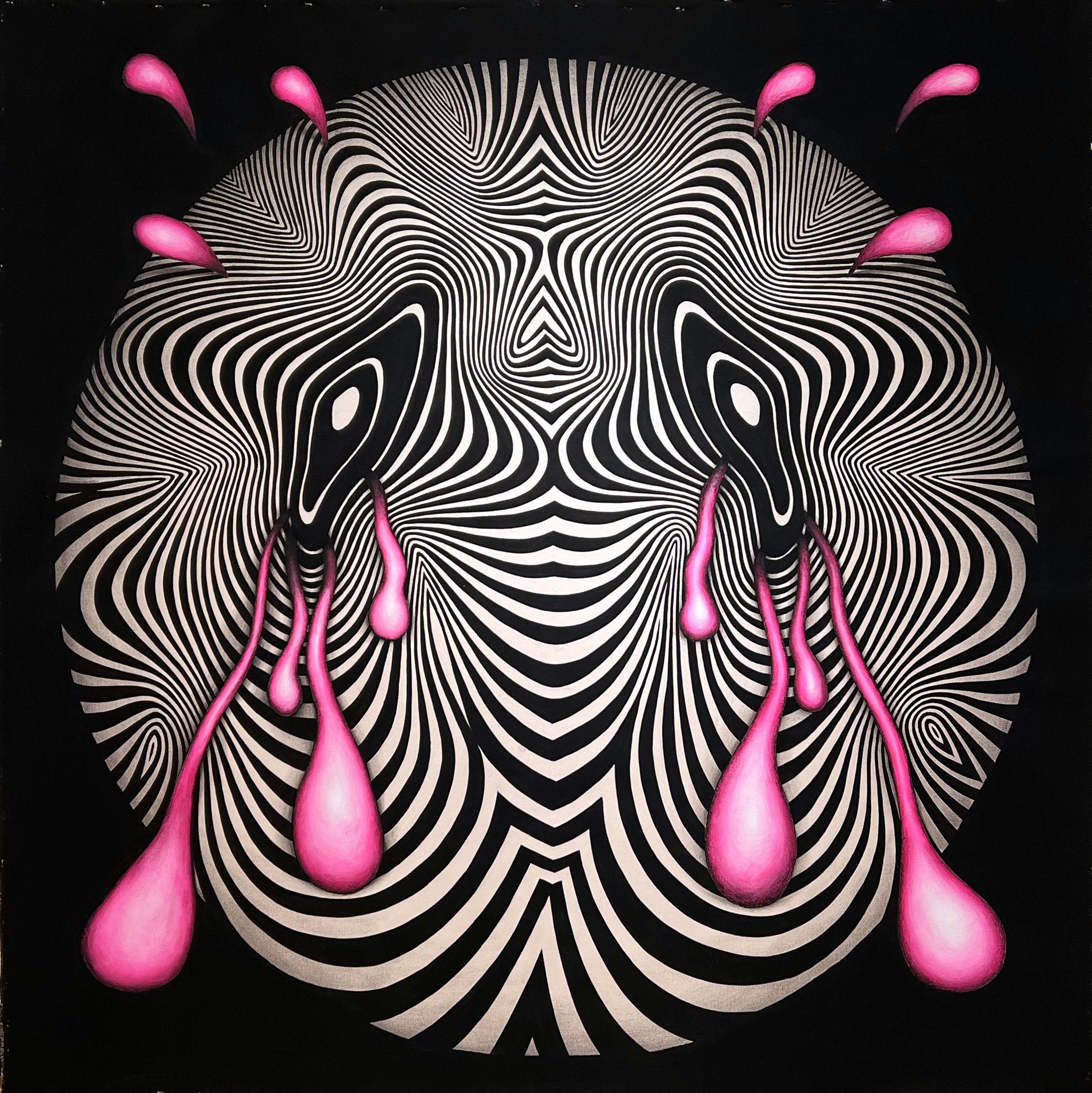

JB: Well, the work in this show is very self-referential, so maybe it’s a result of the world around me that I’m living and creating in. These paintings are much more emotionally explicit than in the past. I’m not making cerebral, symmetrical patterns that are nice to look at; these works are very carefully constructed expressions, and what they express is still up for interpretation. There are fifteen big heads, self-portraits, and they’re crying tears, exploding, going crazy – it’s new territory for me, and it’s vulnerable. I don’t know if it reflects the issue of truth, or post-truth. Maybe the only way to answer your question would be with some perspective, like in five years maybe we’ll look back to this time and say, look how many artists were doing self-portraits! But I don’t think anyone is thinking about it in these terms; we just make the art that we do.

MH: What do you think about beauty? Are we also in a post-beauty moment? The New York art world doesn’t place much value on it. Do you bother yourself with beauty? You have amazing technical skills, but that’s more of a liability than an asset in most circles. How do you negotiate these considerations, or do you ignore it and do whatever you feel like?

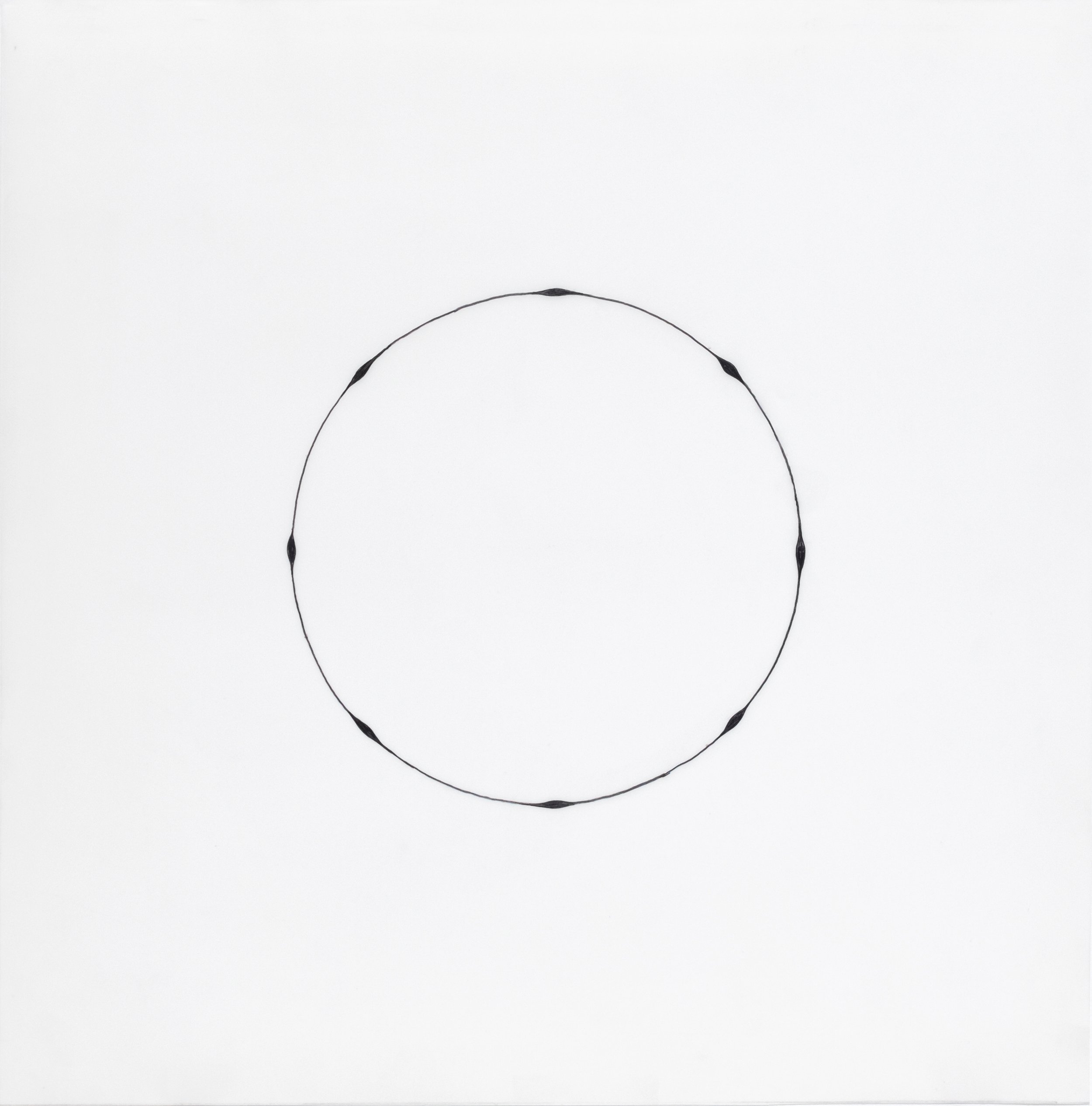

JB: It isn’t a word that I throw around, but I think about beauty, and I think it’s still relevant. I like my work to be beautiful, even if it’s black and white stripes. I want it to be a visual pleasure. And I always want my work to be interesting. If I’m doing a circle, it’s got to be an interesting circle – something that makes me want to look at it longer.

MH: What’s the best part about being an artist?

JB: Having artist friends. I haven’t found another group of people that I’d rather hang out with. When I’m an artist, I’m at home with myself. It’s who I am, who I’ve spent my life being, pursuing this creative process for myself. How it fits into the world, with my life and family and friends, that’s where I find myself. Without it, I don’t know who I am.