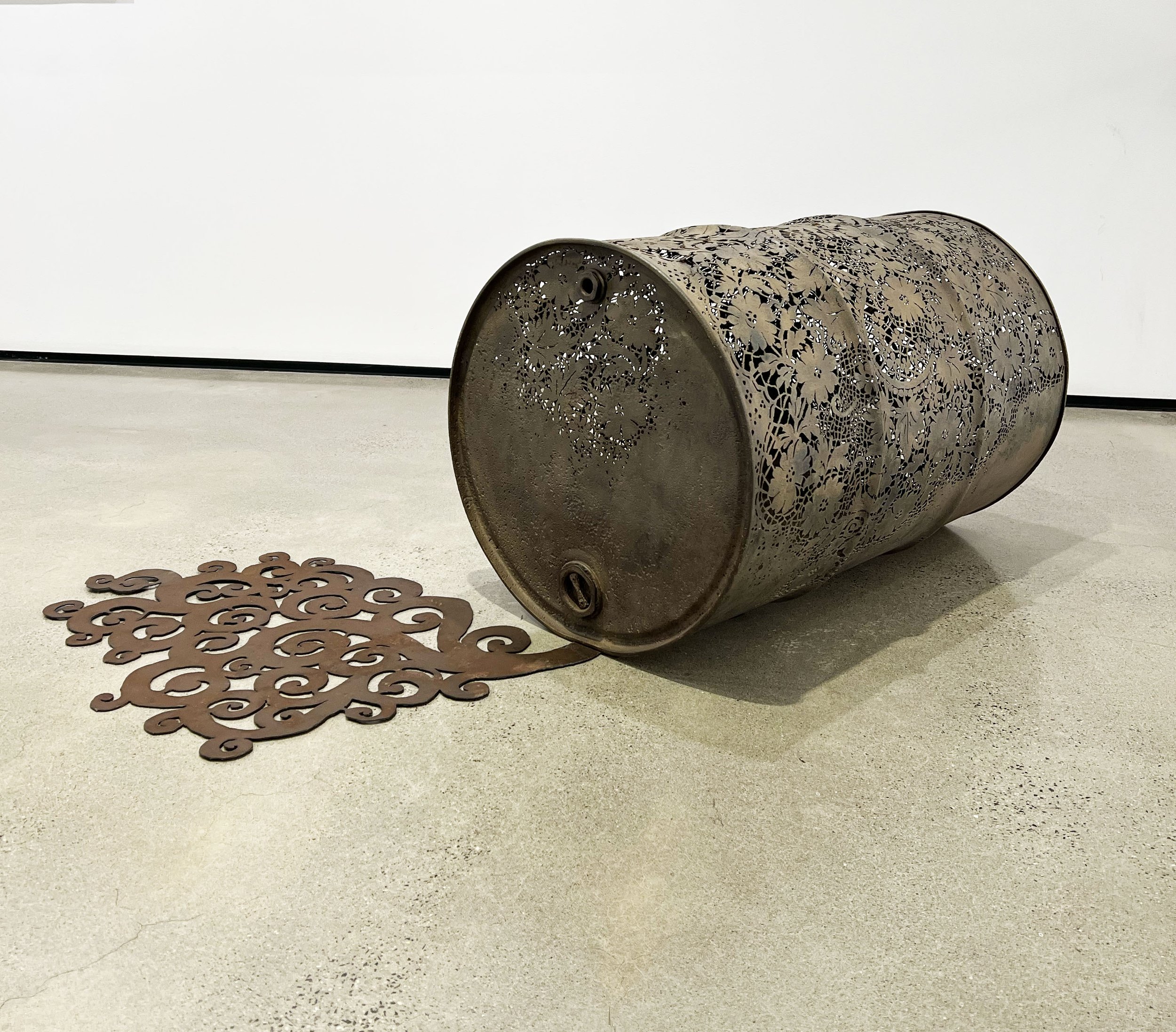

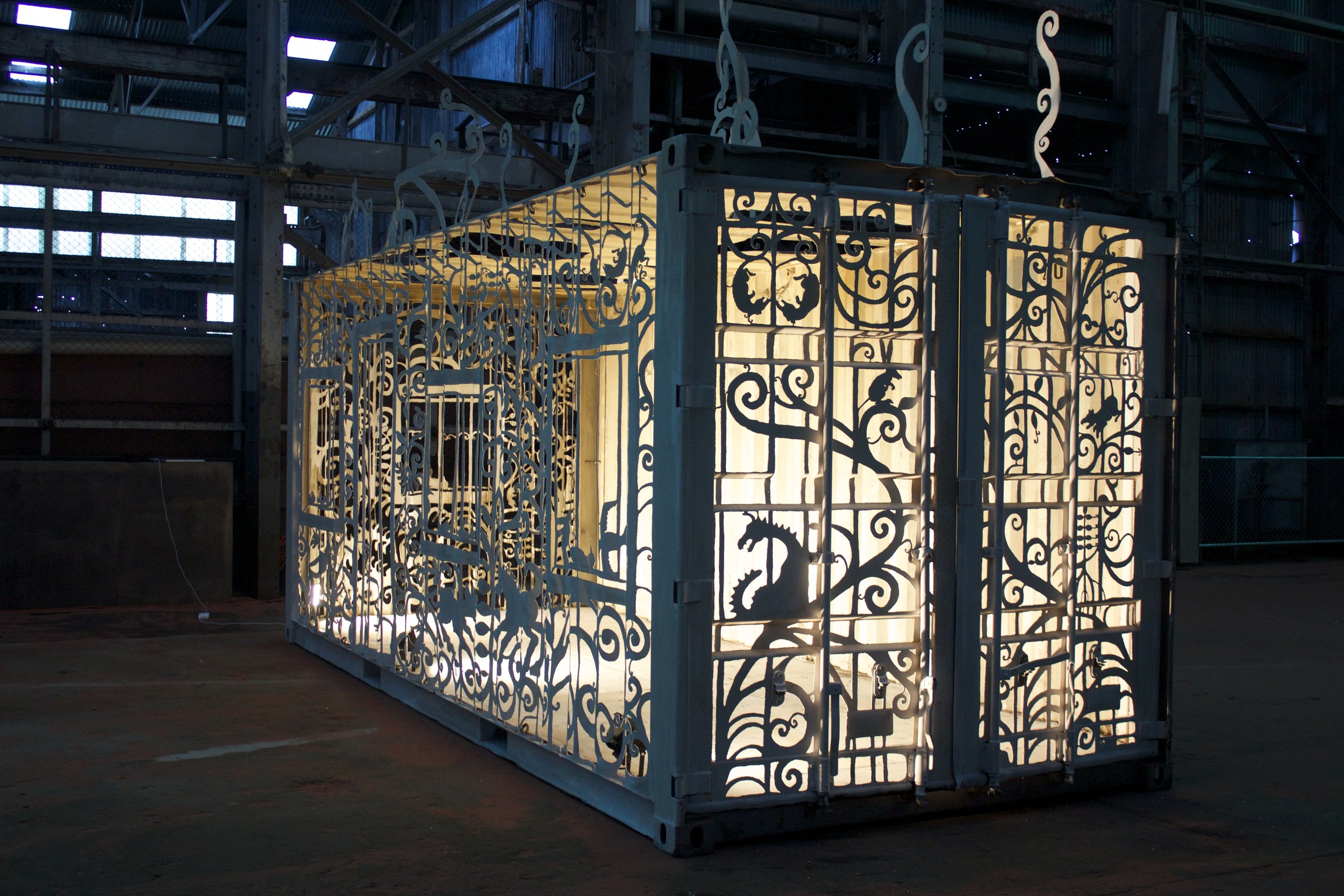

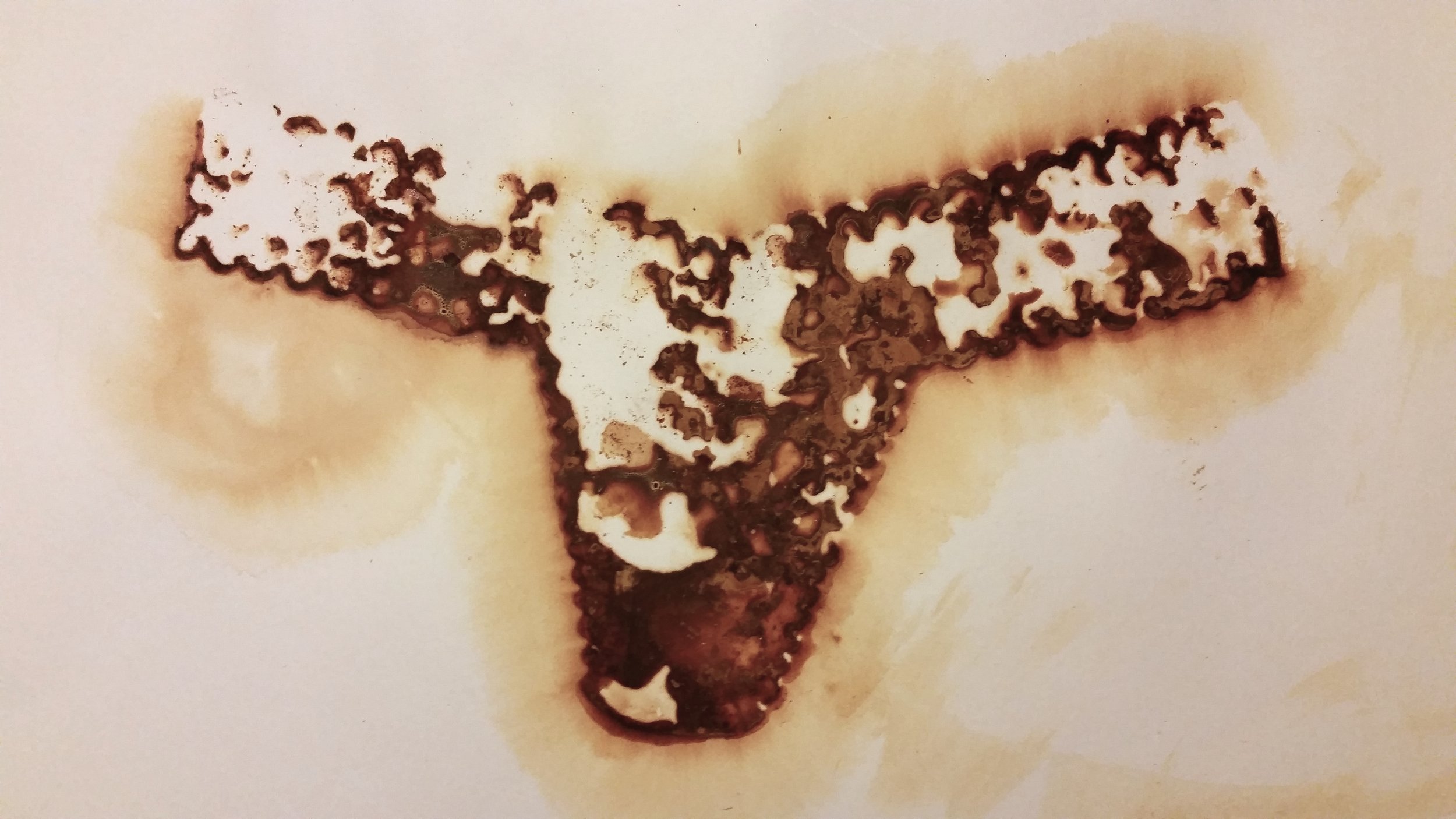

Cal Lane is a mixed media artist best known for transforming industrial steel into intricate, lace-like patterns. She uses plasma cutters and oxyacetylene torches to cut I-beams, oil tanks, and car hoods, undermining their masculine associations with traditional feminine craft. The juxtaposition of blue-collar labor with domestic handicraft creates a tension that goes beyond gender and ornamentation, addressing issues of class, sexuality, and religion. Lane embodies the contradictions in her work, having been employed as a hairdresser and a welder. Her sculptures and two-dimensional works are at once ironic and subversive, confronting the judgments and stereotypes that fuel the power struggles between class and gender.

MH: Your work comes out of a blue-collar profession. Is this allusion intentional? Is it important to you as a conceptual aspect of your work?

CL: I grew up working class. My dad was a naval engineer, and my mom was a hairdresser. I was pushed to follow in her footsteps, so I got my certificate and worked in her salon for a while, but I hated it. My parents discouraged me from going to college. To their way of thinking, you were lucky if you had a job, and hairdressing was a good profession.

MH: What led you to work with steel?

CL: One day I saw this ad in the paper that said, “Become A Welder!” So I did. I went to welding school in my early 20s, and it suited me really well, from day one. When I finished trade school, I was welding tugboats, skyscrapers, and scaffolding. I enjoyed welding as a blue-collar job – the scale and the smell of it were very satisfying, and it fit the rebellious side of me. I didn’t like being pigeonholed as a hairdresser, but I also didn’t like being pigeonholed as a welder. Ironically, when I became a welder, I wanted to be more feminine. I’ve always been that person who pushes against rules and expectations; when someone tells me I can’t do something, that’s what I want to do.

MH: How did you find your way into art?

CL: Besides being a hairdresser, my mom was a painter, so I grew up making art with her. As a kid I was always drawing something, so art has always been in my life. As a welder by trade, I had this idea of taking something big and industrial and carving it away into something delicate. I saw it as poking fun at the “boy’s club” aspect of my profession. Eventually I went to art school and did my undergrad at the Novia Scotia College of Art and Design. I was hired as their metal shop technician and taught a metal working class for their architecture department, which helped pay for college.

MH: Besides the obvious juxtapositions in your work, such as the masculine/feminine and the industrial/handmade angles, I feel like there’s something deeper, not readily apparent. Is there something that is essential to your work, that most people don’t see at first glance?

CL: One of the contrasts that I play with is between the material and the imagery. Steel is this heavy, industrial object that is a symbol of strength and power, and by turning it into lace, it feels like I’m taking away the usefulness of it. I’m undermining it, in a certain sense. I cut lace patterns into oil tanks, oil drums, I-beams, and car hoods, and if people see these as merely decorative objects, I struggle with that. I’m attracted to the decorative in a dark kind of way. It’s funny because I’m often invited to be in group shows centered around lace, but I started making lace because I hated it. My work was a comment on the “decoration” to which women are often reduced, rather than making a decorative object. But I also sometimes incorporate the beautiful aspect of lace as a contrast to the dirty, grungy, dark side of steel working. Both are important and interesting to me.

MH: There’s a strong presence of femininity in your work, as well as an undercurrent of subversion. Is that a correct read, and if so, what are you subverting?

CL: I don’t approach any of my work with a specific way that I want it to be interpreted. I try to keep it engaging and open-ended at the same time. For me, the strength of visual arts is its ambiguity and mystery, so I try to approach things more loosely. Ever since I can remember I’ve been confused by the things that people seem to value. Gender issues, class, religion – any kind of judgment seems random and meaningless to me. It’s constant and it’s exhausting. As a natural rebel, I’m always reacting against my environment, both socially and culturally. I guess I’m embodying the devil’s advocate, always questioning why we have to do anything a certain way. In this way, my work is subversive.

MH: Does the artist choose her medium, or does the medium choose the artist?

CL: I think it goes back and forth. I like having an idea, and then choosing the material for that idea. I don’t just work in steel. I’ve been working on a series of paintings on mattresses, which interest me for their materiality and texture. Each one has a unique quilt pattern, and I like playing off the contrast of the intimate and hideous qualities of a used mattress. I’ve also done some drawings of submarines on embossed wallpaper, which are very pattern oriented. In general, my two-dimensional work has a strong connection to sculpture; I call them paintings because of their rectangular format, and because they hang on the wall.

MH: All artists get to a point where their work becomes repetitive. For some artists that’s not a problem, because the most important thing is to be engaged in the process. For others, they have to move on and find something fresh. Where do you stand on this issue?

CL: Moving on to something fresh is definitely important to me. It helps that I work in several mediums, so I have a variety of things I can work on. I’m aware that my audience is looking for the steel work, but I need to step away from it sometimes, and then when I come back to it, it feels fresh. It can be hard to find the time to experiment when I have too many shows back-to-back and have to produce a body of work.

MH: Is originality important?

CL: I was more concerned with originality early on when I was doing my undergrad. I was a female welder which gave me a unique point of view, and I had teachers pushing me in that direction. But having your own metal shop is overwhelming and expensive. And then I found an oxyacetylene cutting torch at a garage sale for $70, so I started cutting metal. It was the only tool I had, and the limitation was good for me. But steel isn’t just a material for me, it’s also a metaphor for a lot of things, like the masculine and industrial aspect of the material. So I would say that originality has been important to me, but I don’t think about it as much as I used to.

MH: You’ve had a good amount of success in your art career: shows, reviews, articles, and sales. How do you handle disappointment when it comes up?

CL: I’ve always had low expectations! I can thank my upbringing for that. I never expected to have any success, so any form of it comes as a surprise.

MH: What is the highest compliment that you can imagine as an artist?

CL: Well, one guy called me the Jimi Hendrix of plasma cutters.

MH: And as a human being?

CL: A lot of people tell me that I’ve inspired them, which is nice to hear. One guy told me that his 5-year-old daughter started welding because of me, and other women have told me that I inspired them to go into metal work.

MH: What’s something about your work that you’d like people to know, that’s not necessarily obvious?

CL: I was always the artist who was very introverted. As a kid I just stayed home and drew, while all my friends were getting together and partying. But as you get older it completely changes, and now it’s become a communication tool for me. When my work is out in shows and people see it, it’s the primary way that I connect to other people. I’m making the work almost to prove that I’m living on the planet. It’s like I’m asking the question, “Does this make sense to you?”, which is the beginning of a conversation.